Abstract

Background

This paper describes the methods and results of a systematic review to identify instruments used to measure quality of life outcomes in older people. The primary focus of the review was to identify instruments suitable for application with older people within economic evaluations conducted in the aged care sector.

Methods

Online databases searched were PubMed, Medline, Scopus, and Web of Science, PsycInfo, CINAHL, Embase and Informit. Studies that met the following criteria were included: 1) study population exclusively above 65 years of age 2) measured health status, health related quality of life or quality of life outcomes more broadly through use of an instrument developed for this purpose, 3) used a generic preference based instrument or an older person specific preference based or non-preference based instrument or both, and 4) published in journals in the English language after 2000.

Results

The most commonly applied generic preference based instrument in both the community and residential aged care context was the EuroQol - 5 Dimensions (EQ-5D), followed by the Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit (ASCOT) and the Health Utilities Index (HUI2/3). The most widely applied older person specific instrument was the ICEpop CAPability measure for Older people (ICECAP-O) in both community and residential aged care.

Conclusion

In the absence of an ideal instrument for incorporating into economic evaluations in the aged care sector, this review recommends the use of a generic preference based measure of health related quality of life such as the EQ-5D to obtain quality adjusted life years, in combination with an instrument that has a broader quality of life focus like the ASCOT, which was designed specifically for evaluating interventions in social care or the ICECAP-O, a capability measure for older people.

Similar content being viewed by others

A systematic review of outcome measures for economic evaluation in aged care

Background

In the year 2000, 11 % (605 million) of the world’s population was over 60 years of age and this figure is forecast to rise to 21 % (2 billion persons) by 2050 [1]. The fastest growing cohort in this population is the oldest old (over 80 years of age) accounting for 14 % of the older people population in 2014 and expected to increases to over 19 % by 2050 [1]. Older people currently represent the fastest growing age group in most developed countries and are major users of health and aged care services. Aged care services have an important role to play in enhancing the self-worth, independence and quality of life of older people [2, 3]. The projected exponential increase in the prevalence of older people living in the community with cognitive decline, frailty and other co-morbidities will inevitably contribute to a significant increase in the demand for, and utilization of aged care services in the future [1]. Most governments in developed countries subsidise different types of aged care services to enable older people to remain living at home including home care packages to support activities of daily living, nursing care, meals services, adult day care services, equipment and home adaptations, re-ablement services (to assist older people in recovering from and adapting to physical and mental illness) and support for people living with dementia [4–7].

In measuring the impact of service innovations in aged care, researchers in health economics and other disciplines are increasingly recognising that quality of life is a multi-dimensional concept and the impact of interventions for older people goes beyond health status, incorporating psychosocial and emotional well-being, independence, personal beliefs, material well-being and the external environment that influences development and activity [8–10]. Older people’s interpretation of quality of life is based on their capability to achieve those things or participate in activities they value, viewing health as a resource to facilitate their participation in activities of daily living and social interactions [10–14]. The value they obtain from health care services and other interventions goes beyond physical functioning or the health dimensions, as measured by health related quality of life (HRQOL) instruments, to include non-health dimensions such as security in their physical environment, independence, sense of value and attachment, which are only captured by broader instruments [15, 16]. It is therefore important that instruments used to measure and value quality of life outcomes in the aged care sector capture such broader quality of life outcomes.

Instruments for measuring health status and/or quality of life may be differentiated into preference based and non-preference based. Preference based instruments typically incorporate scoring algorithms which are based upon the preferences of a general population sample for the health and/or quality of life states defined by the instrument elicited using one or more valuation methods such as the visual analogue scale (VAS), time trade off (TTO), standard gamble (SG) and discrete choice experiments (DCE) [17, 18]. Preference based instruments are typically used by health economists and health service researchers within economic evaluations in a cost utility analysis framework (CUA) where the main measure of outcome is quality adjusted life years (QALYs). Non-preference based instruments are not suitable for application in CUA because they do not facilitate the calculation of QALYs. Table 1 summarises some of the most popular generic preference based and generic non-preference based instruments.

In contrast to generic preference based instruments, condition specific and population specific preference based instruments focus upon one condition or disease area or population of interest. Population specific preference based instruments have been designed to be utilised with a single population group e.g. children or older people. Examples of population specific preference based instruments include the Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit (ASCOT) [19, 20] designed to measure quality of life for individuals receiving social care and the older person specific ICEpop CAPability measure for Older people (ICECAP-O), a measure of capability [12]. Table 2 summarises some of the most popular older person specific instruments.

This paper describes the methods and results of a systematic review to identify instruments that have been used in measuring quality of life outcomes in older people and documents the contexts in which the instruments have been applied. The primary focus is on instruments suitable for application within a CUA in the aged care sector. The findings from this review will be utilised to inform the design of economic evaluations in community aged care service delivery in Australia. The findings also have wider applicability internationally for researchers designing and conducting economic evaluations with dependent older people in determining the most suitable instruments for application in the aged care sector.

The focus on older-people-specific outcomes is motivated by assertions in the literature that economic evaluations of interventions aimed at older people should be conducted using outcome measures tailored towards meeting the goals of services consumed by older people [16]. Research also indicates that such measures need to capture broader quality of life outcomes such as affection and control that extend beyond health related quality of life whilst also recognising that many older people view health as a resource to facilitate their participation in activities of daily living and social interactions [10, 11, 15]. Different age groups of the population have also been reported to prioritize different areas of life as important, with older people being the most likely to prioritize their health and ability to get out while younger people are more likely to prioritize work, finances, having chances to learn new skills and their sex lives [21–23].

A recent systematic review conducted by Makai and colleagues [15] identified instruments suitable for applications in economic evaluations of interventions in older people receiving long term care. This systematic review builds upon the work previously conducted in two main ways; firstly by capturing the three year period beyond their systematic review and secondly by focusing in more detail upon the particular contexts in which the instrument/s were applied.

Capturing information on and gaining insights into the context within which instruments have been previously applied is particularly relevant in guiding the selection of the most appropriate instrument/s for application within economic evaluation in the aged care sector [24]. Some quality of life instruments have been specifically developed for use within certain settings. For instance, the developers of the ASCOT originally designed the instrument to capture information about an individual’s social-care-related quality of life within community and residential settings [19]. It could also be argued that health-related quality of life instruments such as the EuroQoL 5 dimensions (EQ-5D) are more suitable for individuals receiving health-focussed interventions such as those in hospital where the primary objective is the maintenance of or improvement in health. There is evidence to indicate that there are differences in quality of life perceptions between hospitalised/ambulatory and non-hospitalised older adults [23]. Fassino et al. [25] also showed that aspects of quality of life that matter to dependent older people (individuals dependent on others for their day-to-day living) differ from those that matter to independent older people and a study by Bowling et al. [26] found that better functional ability was related to better quality of life in older age. Bowling et al. [27] also postulated that the multifaceted nature of independence, particularly in older age, is mostly ignored in the wider quality of life measurement literature.

In this study, therefore, we sought to assess whether quality of life instrument use differed according to context, which was defined by the location or setting in which services for older people were being provided, i.e. in the community, residential facilities or within a hospital and according to the level of dependency for older people living in the community (specifically whether the study population was made up of dependent or independent older people). For the purposes of this review, dependency was defined as frailty or individuals dependent in activities of daily living as assessed by instruments such as the Barthel index and individuals who required or lived with an informal carer such as older people with cognitive impairment and those who have experienced or are recovering from stroke. Studies where majority of the study population was comprised of dependent older people were classified under the dependent heading.

Therefore, this paper seeks to provide arguments for the suitability (or otherwise) of the different instruments in economic evaluations of interventions for older people in various contexts within the aged care sector.

Specifically, the three main objectives of the review were:

-

To identify instruments used in the published literature to measure quality of life outcomes for older people

-

To identify the different contexts in which the instruments have been used

-

To provide arguments for the appropriateness and suitability of the different quality of life instruments within a cost utility analysis (CUA) framework of service delivery innovations in aged care.

Review

Methods

The key search questions to be answered by this review were consistent with the three main objectives previously specified. The review process was consistent with the PRISMA guidelines for the conduct of systematic reviews [28].

Databases

PubMed, Medline, CINAHL, Scopus, and Embase, PsycInfo, informit and Web of science.

Search terms

Keywords were replicated based on the review undertaken by Makai et al. [15] with the addition of two more concepts (instruments and the contexts in which quality of life was measured) as well as appropriate subject headings and keywords based on the objectives of this review. Five major concepts were applied in this search; quality of life, the population (older people aged 65 years and over), validity, instruments and study contexts defined as community aged care or residential aged care. These concepts were combined with the ‘AND’ operator. The full search strategy, including subject headings and key words, used in Medline is attached in Additional file 1. The same broad strategy was replicated in other databases with appropriate adjustments made to align the strategy to the requirements of these other databases.

Selection criteria

Studies that met the following criteria were considered: 1) measured quality of life and/or health status and/or health related quality of life as a primary or secondary outcome, either as a snapshot/cross-sectional or longitudinally over time in aged care settings, 2) used a generic or older person specific preference based instrument or a non-preference based older person specific quality of life instrument or both 3) study population was exclusively 65 years and over, dependent older people living in the community or in residential aged care facilities, and 4) published in peer reviewed journals in the English language between 2000 and July 2015.

Studies were excluded if 1) study population was not exclusive to people aged 65 years and over 2) study population was focused primarily upon patients in the health system and/or not comprised of dependent older people living in the community or in residential aged care facilities 3) only disease specific or generic non-preference based measures of quality of life/health related quality of life were used and studies in which quality of life was not measured using an instrument or they used questionnaires specifically designed for the study, 4) dissertations, commentaries, conference papers or review articles and studies for which the full text article could not be obtained.

To assess the reliability of the study selection process, selection was performed by all three authors on a random sample of 5 % of the studies by using the selection criteria described above. The overall agreement was then calculated using Cohen’s kappa statistic [26].

Results

Study selection process

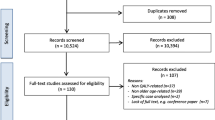

Figure 1 presents the study selection process which was divided into four key stages:

-

i)

Identification: In July 2015, 9545 studies were identified from the online databases and an additional 337 studies from backward/forward searches and basic internet search using the key words. 4969 studies were eliminated because they were found to be duplicates.

-

ii)

Screening: 4913 titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility. 4322 studies were excluded as they did not meet the eligibility criteria.

-

iii)

Eligibility: 591 full texts articles were assessed at this stage. All three authors independently assessed 5 % of the identified studies and overall agreement was then calculated using Cohen’s kappa statistic [28] 380 studies were excluded because they measured quality of life using generic non-preference based instruments while 63 studies used questionnaires specifically designed for the study, the study population in 10 studies was not exclusive to people over 65 years of age and the full text articles could not be obtained for five studies. A further 97 studies were eliminated whose study population was focused primarily upon patients in the health system and/or not comprised of dependent older people living in the community or in residential aged care facilities.

-

iv)

Included: 36 studies were considered in the qualitative synthesis; 26 studies undertaken among dependent older people receiving community aged care services and 10 studies among those residing in aged care facilities. The chance-corrected agreement between the abstracts selected by the primary author and the two co-authors was in the range of 0.77 and 0.88, with an average kappa statistic of 0.81, which was substantial/almost perfect [29].

Key finding 1: study characteristics

Full reports of the included studies were read to extract information relating to the population and country of the research, sample size and type of study, the instrument used and the context in which the instrument/s were applied. Details of all the studies assessed for eligibility and classified by context in this review are provided in Table 3 .

Geographically studies were conducted in several countries; 7 (19 %) from the Netherlands, 6 studies (16 %) each from the UK and Canada, 5 studies (14 %) from the USA(with one study from both USA and Canada) while three studies each (8 %) were from Australia and Italy. 2 studies (5 %) were conducted in Sweden and one study (3 %) each in Poland, Germany, Denmark, Japan and Turkey. The majority of studies (59 %) were undertaken in Europe. Figure 2 is a summary of the geographical distribution of the included studies.

Twenty two studies (61 %) were undertaken using a cross-sectional design, 8 (22 %) randomised control trials, 3 (8 %) prospective cohort studies, 2 (6 %) longitudinal studies and one explorative qualitative study.

The sample sizes varied substantially from a minimum of 10 to a maximum of 29,935 older people. Figure 3 summarises the sample size distributions of included studies.

Key finding 2: contexts and settings

The identified studies were grouped into four contexts; community based dependent, community based independent, residential facility based and hospital based older people (see Table 3). Two contexts were considered to be reflective of older people receiving aged care services; community based dependent older people and older people based in residential aged care facilities. The results reported below therefore relate to these two contexts:

-

a.

Community living dependent older people: Twenty six studies were identified; seven studies conducted in older people with no particular prevailing condition [30–36], ten studies among older people with cognitive impairment [37–46] while seven studies comprised of frail older people where cognitive status was unspecified [24, 47–52]. One study each was among older people with depression [53] and those with a previous stroke [54].

-

b.

Residential aged care context: Ten studies were identified in this context; three among residents with cognitive impairment [55–57], two studies among frail older residents where cognitive status was unspecified [58, 59] and four studies recruited samples from the general resident population who had no cognitive impairment and were not too ill to participate in the study [60–63] while one study specifically considered residents with depression [64].

Key finding 3: instruments used to measure quality of life

Table 4 summarises the instruments that have been used to date to measure quality of life within the community and residential aged care context and Table 5 reports the frequency with which they were used.

In general, the most commonly applied generic preference based instrument was the EQ-5D (51 %) followed by the ASCOT (16 %), and the most widely applied older person specific instrument was the ICECAP-O (11 %) (Table 5). In the community aged care context, the most applied generic instrument was the EQ-5D (n = 16) followed by the ASCOT (n = 6) and HUI3 (n = 5) and the older people specific ICECAP-O (n = 3). Other instruments applied in this sector were the older people specific OPQOL (n = 2) and CASP-19 (n = 1) and the generic QWB (n = 1). In the residential aged care context on the other hand, the most widely applied instrument was the EQ-5D (n = 7) followed by the ICECAP-O (n = 2). Other instruments applied were the ASCOT (n = 1) and the older people specific WHOQoL-Old (n = 1).

The popularity of the EQ-5D may be attributed to several reasons including its brevity, the availability of various translations and scoring algorithms from several cultures and countries worldwide and its recommended use for the economic evaluation of new technologies by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK [65]. The ICECAP-O, CASP-19, OPQOL and ASCOT are all relatively newer instruments developed and validated in the UK. NICE recommends the ASCOT as the preferred measure for outcomes in social care and the ICECAP-O where outcomes in terms of capabilities are to be measured [65].

Five studies explicitly measured quality of life at more than one time point allowing some assessment of the sensitivity to change over time to be made [24, 45, 51, 63, 64]. Absolute changes in utility scores ranged from 0.003 to 0.21 based on 6-18 month follow-up periods. There is no consensus in the literature about what the minimal important difference (MID) should be (i.e. values range from 0.03 [66–68] to 0.074 [69] for changes in EQ-5D [64] and HUI3 utilities [45]). Some of the changes in quality of life reported upon in these studies were larger than the MID value reported in the literature (0.03). However, Drummond [66] indicates that if outcomes based on preference-based measures are to be used to influence resource allocation decisions, it is the difference in cost-effectiveness, such as the incremental cost per QALY, rather than the change in quality of life that is important. This therefore means that within an economic evaluation framework it is important to consider changes in quality of life in addition to the cost of bringing about such changes [66].

Discussion

In considering the suitability of instruments for use in evaluating interventions in the aged care sector, it’s important to consider the aspects of quality of life that are most important to older people and to assess the ability (or otherwise) of each instrument to capture these aspects within the framework of economic evaluation.

This review has highlighted the multi-dimensional nature of quality of life for older people. Key elements of quality of life amongst community living dependent older people include physical and cognitive functioning [32, 34], independence in activities of daily living [37, 47], social relationships [31–33, 47], absence of morbidity or health impairments [32, 33, 51] and pyscho-social wellbeing [32, 38, 51] as well as social connectedness and accessibility within the home and community [36, 47, 50]. In the residential aged care context on the other hand key contributing factors to quality of life include independence in activities of daily living, sense of dignity and physical freedom [55, 58, 60, 70], absence of morbidity or health impairments [58] and happiness coupled with social participation [60, 61].

These findings are consistent with arguments made by several commentators that social participation [71–73], health [10, 71, 72], wealth [72–74], home and community environment [10, 72–75], and independence or control over their life [10, 72, 73] represent key dimensions for any assessment of quality of life in samples of community living dependent older people. In the residential aged care context, important dimensions highlighted in the literature include social participation in family and leisure activities [76–78], independence [76–79], peace and contentment [76, 79], security [77, 79] and spiritual well-being [77, 78].

Generic preference based instruments assess respondents’ level of physical functioning through domains such as mobility within the EQ-5D, 15D and HUI3 and independent living within the AQOL. Psychological and emotional wellbeing is accounted for by anxiety/depression on the EQ-5D and 15D, emotion on HUI3 and happiness and mental health of the AQOL. Relationships and family dimensions may be captured by the relationships domain of the AQOL-8D. However, the question remains as to whether these quality of life dimensions are interpreted in the same way by older people themselves. For example physical functioning in older people may not necessarily be linked solely to their levels of mobility but also to their ability to participate in meaningful activities that emphasise their dignity, independence and relevance to society or their significant relations [58, 71].

Of the preference based instruments identified by this review, the EQ-5D is relatively easy to administer and has a higher completion rate [49, 70, 80–82]. With consideration to respondent burden, the EQ-5D may be considered to have practical advantages as it is relatively brief with only 5 dimensions. The other generic preference based instruments have more dimensions and/or dimension levels as illustrated in Table 1 with several also having mixed response items which may be considered to impose an additional response burden. Research has however shown that the EQ-5D has higher ceiling effects when compared against other instruments such the SF-6D and this needs to be taken into account [49, 83, 84]. The recent development of the new five-level version of the EQ-5D may however minimize this ceiling effect [85, 86]. Coast et al. [87] and Hulme [88] have advocated for interviewer help to complete the instrument when used among the very elderly and those with reduced cognitive function. In fact other researchers have used proxy respondents to apply the instrument to people with mild to moderate cognitive impairment [38, 42, 63, 70]. As highlighted previously, the vast majority of preference based HRQOL instruments such as the EQ-5D were developed for application in a health care context and are narrowly focused on health status alone a dimension highlighted in both community and residential aged care contexts, but it may not be the most appropriate indicator for measuring quality of life in older people. Several researchers have argued that these instruments are unlikely to be appropriate for assessing the well-being of older people in an aged care context because broader quality of life dimensions are important in this context.

The ASCOT is a preference based measure designed to specifically measure social care related quality of life and captures dimensions of quality of life relevant to people receiving social care services [19]. The ASCOT necessarily takes a broader quality of life focus including dimensions such as dignity, safety, control over daily life and social participation which are important for older people in both community and residential aged care [24, 49]. The ASCOT may therefore be considered a relevant instrument to apply when assessing quality of life in relation to service innovations in the aged care sector.

The older person specific instruments identified by this review reflect quality of life in a broader sense and thereby tend to address the majority of key domains previously highlighted as important to older people.

The OPQOL may be considered to represent the most comprehensive older people specific instrument developed to date as it contains quality of life domains/dimensions identified as important for both community and residential aged care contexts and it incorporates both health status and broader quality of life domains [89–91]. However, the OPQOL currently has limited use in an economic evaluation framework because it is not preference based.

The ICECAP-O also encompasses quality of life dimensions that are relevant in both community and residential aged care contexts such as independence or control, security, social participation or attachment, and it has been validated for use in older people in the health and the aged care sectors in several European countries [16, 49, 55, 70, 92]. It is also notable that good construct validity has been reported for the ICECAP-O when used in older people with mild to moderate cognitive impairment, a significant cohort of older people in general [24, 55, 70, 93]. The ICECAP-O is also preference based which potentially facilitates its use in economic evaluations. Some commentators have suggested that the ICECAP-O is not suitable for use in CUA because of its focus on capabilities which does not enable the calculation of QALYs [24, 94]. However, other commentators have indicated that the ICECAP-O may be used within the framework of economic evaluation, with a revised capability based methodology for capturing the benefits associated with new interventions and/or service innovations [95, 96].

Overall for both the community and residential aged care contexts it’s important to emphasize the breadth of dimensions that affect older people’s quality of life. Compared to the EQ-5D, although the ASCOT and ICECAP-O do not have a health dimension per se, they are more sensitive to change and are more associated with broader quality of life beyond health [24]. This review argues that the choice of instrument is determined by the objective of the intervention being assessed; the EQ-5D being preferred for interventions aimed at maintaining health while the ASCOT and ICECAP-O are preferred for interventions with broader benefits beyond health such as service delivery innovations in the aged care sector [24, 49, 55].

A limitation of this study was that due to the heterogeneity of and the lack of adequate data from the studies included in our sample, it was not possible to conduct any meta-correlations or meta-regressions to empirically test whether the instruments used in the studies included in this review perform differently in various contexts.

Conclusions

This review has highlighted that for older people quality of life is a multi-dimensional concept, being defined by broader dimensions of quality of life in addition to health status. Older people typically derive wider quality of life benefits from service innovations in aged care that may or may not also have a positive impact upon health status. In order to reflect the multi-dimensionality of quality of life and to capture wider quality of life benefits within an economic evaluation framework the most appropriate quality of life instrument for application in the aged care sector is one that ideally measures not only health status and functional ability but also wider quality of life dimensions of importance to older people such as independence, psychological wellbeing, social relationships and social connectedness.

Currently no single instrument exists which is preference based and commensurate with the QALY scale (and therefore appropriate for application in economic evaluation) incorporating both health status and the broader elements of quality of life previously highlighted.

In the absence of a single ideal instrument for CUA to assess the cost effectiveness of service innovations in the aged care sector, this review recommends the use of a generic preference based instrument, the EQ-5D to obtain QALYs in combination with the ICECAP-O or the ASCOT to facilitate the measurement and valuation of broader quality of life benefits as defined by older people.

Abbreviations

- 15D:

-

15-Dimensions

- AQOL:

-

Assessment of quality of life

- ASCOT:

-

Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit

- CASP-19:

-

Control Autonomy Self-realization and Pleasure

- CUA:

-

Cost utility analysis

- DCE:

-

Discrete choice experiment

- EQ-5D:

-

EuroQol - 5 Dimensions

- HRQL:

-

Health related quality of life

- HUI2:

-

Health Utilities Index Mark2

- HUI3:

-

Health Utilities Index Mark3

- ICECAP-O:

-

ICEpop CAPability measure for Older people

- NHP:

-

Nottingham Health Profile

- OPQOL:

-

Older People’s Quality of Life

- QALYs:

-

Quality adjusted life years

- QWB:

-

Quality of Wellbeing scale

- SF-12:

-

Short Form 12

- SF-36:

-

Short Form 36

- SF-6D:

-

Short Form 6 Dimensions

- SG:

-

Standard gamble

- TTO:

-

Time trade off

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

- WHOQoL-Bref:

-

World Health Organisation Quality of Life brief instrument

- WHOQoL-Old:

-

World Health Organisation Quality of Life Instrument-Older Adults Module

References

United Nations. Population ageing and sustainable development. In: Population Facts, Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. 2014.

Sangl J, Saliba D, Gifford DR, Hittle DF. Challenges in measuring nursing home and home health quality: lessons from the First National Healthcare Quality Report. Med Care. 2005;43:I24–32.

Shekelle PG, MacLean CH, Morton SC, Wenger NS. Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders: Methods for Developing Quality Indicators. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:647–52.

Gasior K, Huber M, Lamura G, Lelkes O, Marin B, Rodrigues R, Schmidt A, Zólyomi E: Facts and Figures on Healthy Ageing and Long-term Care. (Rodrigues R, Huber M, Lamura G eds.). Vienna: European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research; 2012.

Secretary of State for Health: Caring for our future: reforming care and support. (Health Do ed. United Kingdom: The Stationery Office Limited; 2012.

Administration on Aging (AoA) [http://www.aoa.gov/].

Department of Health and Ageing- Australian Government. Living longer. Living better: aged care reform package. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, Australian Government; 2012.

Felce D, Perry J. Quality of life: its definition and measurement. Res Dev Disabil. 1995;16:51–74.

WHOQOL GROUP. Measuring quality of life: the development of the World Health Organization Quality of Life Instrument (WHOQoL). Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993.

Milte CM, Walker R, Luszcz MA, Lancsar E, Kaambwa B, Ratcliffe J: How important is health status in defining quality of life for older people? an exploratory study of the views of older South Australians. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2013, 12.

Davis JC, Liu-Ambrose T, Richardson CG, Bryan S. A comparison of the ICECAP-O with EQ-5D in a falls prevention clinical setting: are they complements or substitutes? Qual Life Res. 2013;22:969–77.

Coast J, Flynn TN, Natarajan L, Sproston K, Lewis J, Louviere JJ, et al. Valuing the ICECAP capability index for older people. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:874–82.

Grewal I, Lewis J, Flynn T, Brown J, Bond J, Coast J. Developing attributes for a generic quality of life measure for older people: Preferences or capabilities? Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:1891–901.

Hickey A, Barker M, McGee H, O'Boyle C. Measuring health-related quality of life in older patient populations: a review of current approaches. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23:971–93.

Makai P, Brouwer WBF, Koopmanschap MA, Stolk EA, Nieboer AP. Quality of life instruments for economic evaluations in health and social care for older people: A systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2014;102:83–93.

Coast J, Peters TJ, Natarajan L, Sproston K, Flynn T. An assessment of the construct validity of the descriptive system for the ICECAP capability measure for older people. Qual Life Res. 2008;17:967–76.

Brazier J, Ratcliffe J, Salomon AJ, Tsuchiya A. Methods for obtaining health state values: generic preference based measures of health and the alternatives. In: Measuring and Valuing Health Benefits for Economic Evaluation. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. p. 175–256.

Drummond FM, Sculpher JM, Torrance WG, O'brien JB, Stoddart LG. Multi-attribute health status classification systems with preference scores. In: Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programs. Thirdth ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005a. p. 154–72.

Netten A, Burge P, Malley J, Potoglou D, Towers A. Outcomes of social care for adults: developing a preference weighted measure. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16:165.

Netten A, Beadle-Brown J, Caiels J, Forder J, Malley J, Smith N, et al. Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit v2.1: Main guidance. In: PSSRU Discussion Paper Personal Social Services Research Unit. Canterbury: University of Kent; 2011.

Bowling A. What things are important in people’s lives? Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:1447–62.

Bowling A. The most important things in life. Comparisons between older and younger population age groups by gender. International Journal of Health Sciences. 1995;6:169–75.

Kalfoss M, Halvorsrud L. Important Issues to Quality of Life Among Norwegian Older Adults: An Exploratory Study. The Open Nursing Journal. 2009;3:45–55.

van Leeuwen KM, Bosmans JE, Jansen APD, Hoogendijk EO, van Tulder MW, van der Horst HE, et al. Comparing Measurement Properties of the EQ-5D-3L, ICECAP-O, and ASCOT in Frail Older Adults. Value in Health (Wiley-Blackwell). 2015;18:35–43.

Fassino S, Leombruni P, Abbate Daga G, Brustolin A, Rovera GG, Abris F. Quality of life in dependent older adults living at home. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2002;35:9–20.

Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Education and Psychological Measures. 1960;20:37–46.

Bowling AZG, Dykes J, Dowding LM, Evans O, Fleissig A, Banister D, et al. Let's ask them: a national survey of definitions of quality of life and its enhancement among people aged 65 and over. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2003;56:269–306.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6, e1000097.

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74.

Malley JN, Towers A-M, Netten AP, Brazier JE, Forder JE, Flynn T. An assessment of the construct validity of the ASCOT measure of social care-related quality of life with older people. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2012;10:1–14.

Forder JE, Caiels J. Measuring the outcomes of long-term care. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:1766–74.

Borowiak E, Kostka T. Predictors of quality of life in older people living at home and in institutions. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2004;16:212–20.

Maxwell CJ, Kang J, Walker JD, Zhang JX, Hogan DB, Feeny DH, et al. Sex differences in the relative contribution of social and clinical factors to the Health Utilities Index Mark 2 measure of health-related quality of life in older home care clients. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2009;7:80.

McPhail S, Lane P, Russell T, Brauer SG, Urry S, Jasiewicz J, et al. Telephone reliability of the Frenchay Activity Index and EQ-5D amongst older adults. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2009;7:1–8.

Makai P, Koopmanschap MA, Brouwer WB, Nieboer AA. A validation of the ICECAP-O in a population of post-hospitalized older people in the Netherlands. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2013;11:1–11.

van Leeuwen KM, Malley J, Bosmans JE, Jansen APD, Ostelo RW, van der Horst HE, et al. What can local authorities do to improve the social care-related quality of life of older adults living at home? Evidence from the Adult Social Care Survey. Health & Place. 2014;29:104–13.

Andersen C, Wittrup-Jensen K, Lolk A, Andersen K, Kragh-Sørensen P. Ability to perform activities of daily living is the main factor affecting quality of life in patients with dementia. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2004;2:1–7.

Snow AL, Dani R, Souchek J, Sullivan G, Ashton CM, Kunik ME. Comorbid psychosocial symptoms and quality of life in patients with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2005;13:393–401.

Greene T, Camicioli R. Depressive Symptoms and Cognitive Status Affect Health-Related Quality of Life in Older Patients with Parkinson's Disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1888–90.

Oremus M, Tarride JE, Clayton N, Canadian Willingness-to-Pay Study Group, Raina P. Health utility scores in Alzheimer's disease: differences based on calculation with American and Canadian preference weights. Value Health. 2014;17:77–83.

Kleiner-Fisman G, Stern MB, Fisman DN. Health-Related Quality of Life in Parkinson disease: Correlation between Health Utilities Index III and Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) in U.S. male veterans. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2010;8:1–9.

Naglie G, Hogan DB, Krahn M, Black SE, Beattie BL, Patterson C, et al. Predictors of Family Caregiver Ratings of Patient Quality of Life in Alzheimer Disease: Cross-Sectional Results from the Canadian Alzheimer's Disease Quality of Life Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2011;19:891–901.

Naglie G, Hogan DB, Krahn M, Beattie BL, Black SE, MacKnight C, et al. Predictors of Patient Self-Ratings of Quality of Life in Alzheimer Disease: Cross-Sectional Results From the Canadian Alzheimer's Disease Quality of Life Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2011;19:881–90.

Kunz S. Psychometric properties of the EQ-5D in a study of people with mild to moderate dementia. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:425–34.

Kavirajan H, Hay SRD, Vassar S, Vickrey BG. Responsiveness and construct validity of the health utilities index in patients with dementia. Med Care. 2009;47:651–61.

Schölzel-Dorenbos CJM, Arons AMM, Wammes JJG, Rikkert M, Krabbe PFM. Validation study of the prototype of a disease-specific index measure for health-related quality of life in dementia. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2012;10:1–11.

Bilotta C, Bowling A, Case A, Nicolini P, Mauri S, Castelli M, et al. Dimensions and correlates of quality of life according to frailty status: a cross-sectional study on community-dwelling older adults referred to an outpatient geriatric service in Italy. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2010;8:10.

van Leeuwen K, Bosmans J, Jansen A, Rand S, Towers A-M, Smith N, et al. Dutch translation and cross-cultural validation of the Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit (ASCOT). Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2015;13:1–13.

van Leeuwen KM, Jansen APD, Muntinga ME, Bosmans JE, Westerman MJ, van Tulder MW, et al. Exploration of the content validity and feasibility of the EQ-5D-3L, ICECAP-O and ASCOT in older adults. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:1–10.

Theeke LA, Mallow J. Loneliness and Quality of Life in Chronically Ill Rural Older Adults. Am J Nurs. 2013;113:28–37.

Zhang JX, Walker JD, Wodchis WP, Hogan DB, Feeny DH, Maxwell CJ. Measuring health status and decline in at-risk seniors residing in the community using the Health Utilities Index Mark 2. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:1415–26.

Bilotta C, Bowling A, Nicolini P, Casè A, Pina G, Rossi S, et al. Older People's Quality of Life (OPQOL) scores and adverse health outcomes at a one-year follow-up. A prospective cohort study on older outpatients living in the community in Italy. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2011a;9:1–10.

Bilotta C, Bergamaschini L, Spreafico S, Vergani C. Day care centre attendance and quality of life in depressed older adults living in the community. European Journal of Ageing. 2010;7:29–35.

Vahlberg B, Cederholm T, Lindmark B, Zetterberg L, Hellstrom K. Factors Related to Performance-Based Mobility and Self-reported Physical Activity in Individuals 1–3 Years after Stroke: A Cross-sectional Cohort Study. Journal of Stroke & Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2013;22:E426–34.

Makai P, Brouwer WB, Koopmanschap MA, Nieboer AP. Capabilities and quality of life in Dutch psycho-geriatric nursing homes: an exploratory study using a proxy version of the ICECAP-O. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:801–12.

Yamanaka K, Kawano Y, Noguchi D, Nakaaki S, Watanabe N, Amano T, et al. Effects of cognitive stimulation therapy Japanese version (CST-J) for people with dementia: A single-blind, controlled clinical trial. Aging and Mental Health. 2013;17:579–86.

Wolfs C, Dirksen C, Kessels A, Willems D, Verhey F, Severens J. Performance of the EQ-5D and the EQ-5D+C in elderly patients with cognitive impairments. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2007;5:1–10.

Sitoh YY, Lau TC, Zochling J, Schwarz J, Chen JS, March LM, et al. Determinants of health-related quality of life in institutionalised older persons in northern Sydney. Internal Medicine Journal. 2005;35:131–4.

Comans TA, Peel NM, Gray LC, Scuffham PA. Quality of life of older frail persons receiving a post-discharge program. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:1477–7525.

Netten A, Trukeschitz B, Beadle-Brown J, Forder J, Towers AM, Welch E. Quality of life outcomes for residents and quality ratings of care homes: is there a relationship? Age & Ageing. 2012;41:512–7.

Top M, Dikmetas E. Quality of life and attitudes to ageing in Turkish older adults at old people's homes. Health Expect. 2015;18:288–300.

Torma J, Winblad U, Saletti A, Cederholm T. Strategies to Implement Community Guidelines on Nutrition and their Long-term Clinical Effects in Nursing Home Residents. Journal of Nutrition Health & Aging. 2015;19:70–6.

Devine A, Taylor SJC, Spencer A, Diaz-Ordaz K, Eldridge S, Underwood M. The agreement between proxy and self-completed EQ-5D for care home residents was better for index scores than individual domains. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:1035–43.

Underwood M, Lamb S, Eldridge S, Sheehan B, Slowther A. Exercise for depression in care home residents: a randomised controlled trial with cost-effectiveness analysis (OPERA). Health Technol Assess. 2013;17:281.

NICE: The social care guidance manual. (Excellence NIfHaC ed. pp. 99; 2013:99.

Drummond M. Introducing Economic and Quality of Life Measurements into Clinical Studies. Ann Med. 2001;33:344–9.

Dobrez D, Cella D, Pickard AS, Lai J-S, Nickolov A. Estimation of Patient Preference-Based Utility Weights from the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—General. Value Health. 2007;10:266–72.

Cheung Y-B, Thumboo J, Gao F, Ng G-Y, Pang G, Koo W-H, et al. Mapping the English and Chinese Versions of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General to the EQ-5D Utility Index. Value Health. 2009;12:371–6.

Walters S, Brazier J. Comparison of the minimally important difference for two health state utility measures: EQ-5D and SF-6D. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1523–32.

Makai P, Beckebans F, van Exel J, Brouwer WBF. Quality of Life of Nursing Home Residents with Dementia: Validation of the German Version of the ICECAP-O. PLoS One. 2014;9, e92016.

Nilsson M, Ekman S, Sarvimaki A. Ageing with joy or resigning to old age: older people's experiences of the quality of life in old age. Health Care in Later Life. 1998;3:94–110.

Gabriel Z, Bowling A. Quality of life from the perspectives of older people. Ageing Soc. 2004;24:675–91.

Levasseur M, St-Cyr Tribble D, Desrosiers J. Meaning of quality of life for older adults: importance of human functioning components. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;49:1.

Borglin G, Edberg A-K, Rahm Hallberg I. The experience of quality of life among older people. J Aging Stud. 2005;19:201–20.

Levasseur M, Desrosiers J, St-Cyr Tribble D. Do quality of life, participation and environment of older adults differ according to level of activity? Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:1477–7525.

Hall S, Opio D, Dodd RH, Higginson IJ. Assessing quality-of-life in older people in care homes. Age Ageing. 2011;40:507–12.

Kane RA. Long-term care and a good quality of life: bringing them closer together. Gerontologist. 2001;41:293–304.

Tester S, Hubbard G, Downs M, MacDonald C, Murphy J. What does quality of life mean for frail residents? Nursing & Residential Care. 2004;6:89–92.

Hjaltadóttir I, Gústafsdóttir M. Quality of life in nursing homes: perception of physically frail elderly residents. Scand J Caring Sci. 2007;21:48–55.

Holland R, Smith RD, Harvey I, Swift L, Lenaghan E. Assessing quality of life in the elderly: A direct comparison of the EQ-5D and AQoL. Health Econ. 2004;13:793–805.

Gerard K, Mehta R, Mullee M, Nicholson T, Roderick P. EQ-5D versus SF-6D in an older, chronically ill patient group. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy. 2004;3:91+.

Davis JC, Bryan S, McLeod R, Rogers J, Khan K, Liu-Ambrose T. Exploration of the association between quality of life, assessed by the EQ-5D and ICECAP-O, and falls risk, cognitive function and daily function, in older adults with mobility impairments. BMC Geriatr. 2012;12:1–7.

Brazier J, Roberts J, Tsuchiya A, Busschbach J. A comparison of the EQ-5D and SF-6D across seven patient groups. Health Econ. 2004;13:873–84.

Wu J, Han Y, Zhao F-L, Zhou J, Chen Z, Sun H. Validation and comparison of EuroQoL-5 dimension (EQ-5D) and Short Form-6 dimension (SF-6D) among stable angina patients. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2014;12:1–11.

Janssen MF, Pickard AS, Golicki D, Gudex C, Niewada M, Scalone L, et al. Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L across eight patient groups: a multi-country study. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:1717–27.

Janssen MF, Birnie E, Bonsel GJ. Quantification of the level descriptors for the standard EQ-5D three-level system and a five-level version according to two methods. Qual Life Res. 2008;17:463–73.

Coast J, Peters TJ, Richards SH, Gunnell DJ. Use of the EuroQoL among elderly acute care patients. Qual Life Res. 1998;7:1–10.

Hulme C, Long AF, Kneafsey R, Reid G. Using the EQ-5D to assess health-related quality of life in older people. Age Ageing. 2004;33:504–7.

Bowling A. The Psychometric Properties of the Older People's Quality of Life Questionnaire, Compared with the CASP-19 and the WHOQOL-OLD. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research. 2009;2009:12.

Bowling A, Banister D, Sutton S, Evans O, Windsor J. A multidimensional model of the quality of life in older age. Aging Ment Health. 2002;6:355–71.

Hendry F, McVittie C. Is quality of life a healthy concept? Measuring and understanding life experiences of older people. Qual Health Res. 2004;14:961–75.

Flynn TN, Chan P, Coast J, Peters TJ. Assessing quality of life among British older people using the ICEPOP CAPability (ICECAP-O) measure. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2011;9:317–29.

Purser JL, Fillenbaum GG, Pieper CF, Wallace RB. Mild cognitive impairment and 10-year trajectories of disability in the Iowa Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly cohort. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1966–72.

Rowen D, Brazier J, Van Hout B. A Comparison of Methods for Converting DCE Values onto the Full Health-Dead QALY Scale. Med Decis Mak. 2014;35:328–40.

Mitchell PM, Roberts TE, Barton PM, Coast J. Assessing sufficient capability: A new approach to economic evaluation. Soc Sci Med. 2015;139:71–9.

Cookson R. QALYs and the capability approach. Health Econ. 2005;14:817–29.

EuroQol Group: EQ-5D.

Horsman J, Furlong W, Feeny D, Torrance G. The Health Utilities Index (HUI): concepts, measurement properties and applications. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2003;1:54.

Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J Health Econ. 2002;21:271–92.

Assessment of Quality of Life - instruments [http://www.aqol.com.au/].

Brazier J, Ratcliffe J, Salomon AJ, Tsuchiya A. Measuring and Valuing Health Benefits for Economic Evaluation. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007c.

Sintonen H, Pekurinen M. A fifteen-dimensional measure of health-related quality of life (15D) and its applications. In: Walker S, Rosser R, editors. Quality of Life Assessment: Key Issues in the 1990s. Netherlands: Springer; 1993. p. 185–95.

SF-36.org: SF-36.org: A community for measuring health outcomes using SF tools.

Group WHOQOL. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF Quality of Life Assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551–8.

Wiklund I. The Nottingham Health Profile--a measure of health-related quality of life. Scand J Prim Health Care Suppl. 1990;1:15–8.

Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, Janssen MF, Kind P, Parkin D, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. 2011;20.

Hyde M, Wiggins RD, Higgs P, Blane DB. A measure of quality of life in early old age: The theory, development and properties of a needs satisfaction model (CASP-19). Aging and Mental Health. 2003;7:186–94.

Power M, Quinn K, Schmidt S. Development of the WHOQOL-old module. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:2197–214.

Windle G, Edwards R, Burholt V. A concise alternative for researching health-related quality of life in older people. Quality in Ageing. 2004;5:13–24.

Roalfe AK, Bryant TL, Davies MH, Hackett TG, Saba S, Fletcher K, et al. A cross-sectional study of quality of life in an elderly population (75 years and over) with atrial fibrillation: secondary analysis of data from the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged study. Europace. 2012;14:1420–7.

Bowling A, Hankins M, Windle G, Bilotta C, Grant R. A short measure of quality of life in older age: The performance of the brief Older People's Quality of Life questionnaire (OPQOL-brief). Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;56:181–7.

Ratcliffe J, Lester LH, Couzner L, Crotty M. An assessment of the relationship between informal caring and quality of life in older community-dwelling adults – more positives than negatives? Health & Social Care in the Community. 2013;21:35–46.

Johansson MM, Marcusson J, Wressle E. Cognition, daily living, and health-related quality of life in 85-year-olds in Sweden. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 2012;19:421–32.

AbiHabib LE, Chemaitelly HS, Jaalouk LY, Karam NE. Developing capacities in aging studies in the Middle East: Implementation of an Arabic version of the CANE IV among community-dwelling older adults in Lebanon. Aging & Mental Health. 2011;15:605–17.

Peters LL, Boter H, Slaets JP, Buskens E. Development and measurement properties of the self assessment version of the INTERMED for the elderly to assess case complexity. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74:518–22.

Okamoto N, Hisashige A, Tanaka Y, Kurumatani N: Development of the Japanese 15D instrument of health-related quality of life: verification of reliability and validity among elderly people. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource] 2013, 8.

Olsson IN, Runnamo R, Engfeldt P. Drug treatment in the elderly: an intervention in primary care to enhance prescription quality and quality of life. 2012.

Ploeg J, Brazil K, Hutchison B, Kaczorowski J, Dalby DM, Goldsmith CH, Furlong W: Effect of preventive primary care outreach on health related quality of life among older adults at risk of functional decline: randomised controlled trial. Bmj 1480, 340.

Vaapio S, Salminen M, Vahlberg T, Sjosten N, Isoaho R, Aarnio P, et al. Effects of risk-based multifactorial fall prevention on health-related quality of life among the community-dwelling aged: a randomized controlled trial. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:20.

Pihl E, Cider Å, Strömberg A, Fridlund B, Mårtensson J. Exercise in Elderly Patients with Chronic Heart Failure in Primary Care: Effects on Physical Capacity and Health-Related Quality of Life. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;10:150–8.

Thiem U, Klaaßen-Mielke R, Trampisch U, Moschny A, Pientka L, Hinrichs T. Falls and EQ-5D rated quality of life in community-dwelling seniors with concurrent chronic diseases: a cross-sectional study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2014;12:2.

Davis JC, Marra CA, Liu-Ambrose TY. Falls-related self-efficacy is independently associated with quality-adjusted life years in older women. Age Ageing. 2011;40:340–6.

Sacanella E, Pérez-Castejón J, Nicolás J, Masanés F, Navarro M, Castro P, et al. Functional status and quality of life 12 months after discharge from a medical ICU in healthy elderly patients: a prospective observational study. Crit Care. 2011;15:1–9.

Yoon HS, Kim HY, Patton LL, Chun JH, Bae KH, Lee MO. Happiness, subjective and objective oral health status, and oral health behaviors among Korean elders. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2013;41:459–65.

Konig HH, Heider D, Lehnert T, Riedel-Heller SG, Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H, Vilagut G, Bruffaerts R, Haro JM, de Girolamo G, et al.: Health status of the advanced elderly in six European countries: results from a representative survey using EQ-5D and SF-12. Health & Quality of Life Outcomes 2010, 8.

Sawka AM, Thabane L, Papaioannou A, Gafni A, Ioannidis G, Papadimitropoulos EA, et al. Health-related quality of life measurements in elderly Canadians with osteoporosis compared to other chronic medical conditions: a population-based study from the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos). Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:1836–40.

Kim KI, Lee JH, Kim CH. Impaired Health-Related Quality of Life in Elderly Women is Associated With Multimorbidity: Results From the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Gender Medicine. 2012;9:309–18.

Kostka T, Bogus K. Independent contribution of overweight/obesity and physical inactivity to lower health-related quality of life in community-dwelling older subjects. Zeitschrift Fur Gerontologie Und Geriatrie. 2007;40:43–51.

Hage C, Mattsson E, Ståhle A. Long term effects of exercise training on physical activity level and quality of life in elderly coronary patients — A three- to six-year follow-up. Physiother Res Int. 2003;8:13–22.

Peel NM, Bartlett HP, Marshall AL. Measuring quality of life in older people: reliability and validity of WHOQOL-OLD. Australasian Journal on Ageing. 2007;26:162–7.

Nordin OI, Runnamo R, Engfeldt P: Medication quality and quality of life in the elderly, a cohort study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2011, 9.

Laudisio A, Marzetti E, Antonica L, Pagano F, Vetrano DL, Bernabei R, et al. Metabolic syndrome and quality of life in the elderly: age and gender differences. Eur J Nutr. 2013;52:307–16.

Davis JC, Best JR, Bryan S, Li LC, Hsu CL, Gomez C, Vertes K, Liu-Ambrose T: Mobility Is a Key Predictor of Change in Well-Being Among Older Adults Who Experience Falls: Evidence From the Vancouver Falls Prevention Clinic Cohort. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2015.

Sacanella E, Perez-Castejon JM, Nicolas JM, Masanes F, Navarro M, Castro P, et al. Mortality in healthy elderly patients after ICU admission. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:550–5.

de Vries OJ, Peeters G, Elders PJM, Muller M, Knol DL, Danner SA, et al. Multifactorial Intervention to Reduce Falls in Older People at High Risk of Recurrent Falls A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1110–7.

Hunger M, Thorand B, Schunk M, Doring A, Menn P, Peters A, et al. Multimorbidity and health-related quality of life in the older population: results from the German KORA-age study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:1477–7525.

Oster G, Harding G, Dukes E, Edelsberg J, Cleary PD. Pain, Medication Use, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Older Persons With Postherpetic Neuralgia: Results From a Population-Based Survey. The Journal of Pain. 2005;6:356–63.

Lantz K, Marcusson J, Wressle E. Perceived Participation and Health-Related Quality of Life in 85 Year Olds in Sweden. Otjr-Occupation Participation and Health. 2012;32:117–25.

Sawatzky R, Liu-Ambrose T, Miller WC, Marra CA. Physical activity as a mediator of the impact of chronic conditions on quality of life in older adults. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:68.

Fusco O, Ferrini A, Santoro M, Lo Monaco MR, Gambassi G, Cesari M. Physical function and perceived quality of life in older persons. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2012;24:68–73.

Franic DM, Jiang JZ. Potentially Inappropriate Drug Use and Health-Related Quality of Life in the Elderly. Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy. 2006;26:768–78.

Cahir C, Bennett K, Teljeur C, Fahey T. Potentially inappropriate prescribing and adverse health outcomes in community dwelling older patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77:201–10.

Bowling A, Iliffe S. Psychological approach to successful ageing predicts future quality of life in older adults. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2011;9:1–10.

Choi M, Ahn S, Jung D: Psychometric evaluation of the Korean Version of the Self-Efficacy for Exercise Scale for older adults. Geriatric Nursing 2015.

Lima FM, Hyde M, Chungkham HS, Correia C, Campos AS, Campos M, Novaes M, Laks J, Petribu K: Quality of life amongst older brazilians: A cross-cultural validation of the CASP-19 into brazilian-portuguese. PLoS ONE 2014, 9.

Chen Y, Hicks A, While AE: Quality of life and related factors: a questionnaire survey of older people living alone in Mainland China. Quality of Life Research 2014.

Bilotta C, Bowling A, Nicolini P, Casè A, Vergani C. Quality of life in older outpatients living alone in the community in Italy. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2012;20:32–41.

Salkeld G, Cameron ID, Cumming RG, Easter S, et al. Quality of life related to fear of falling and hip fracture in older women: A time trade off study / Commentary. Br Med J. 2000;320:341–6.

Groessl EJ, Kaplan RM, Cronan TA. Quality of well-being in older people with osteoarthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2003;49:23–8.

Kvamme J-M, Olsen JA, Florholmen J, Jacobsen BK. Risk of malnutrition and health-related quality of life in community-living elderly men and women: The Tromsø study. Qual Life Res. 2011;20:575–82.

Davis JC, Liu-Ambrose T, Khan KM, Robertson MC, Marra CA. SF-6D and EQ-5D result in widely divergent incremental cost-effectiveness ratios in a clinical trial of older women: implications for health policy decisions. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:1849–57.

Stepnowsky C, Johnson S, Dimsdale J, Ancoli-Israel S. Sleep apnea and health-related quality of life in African-American elderly. Ann Behav Med. 2000;22:116–20.

Hartholt KA, van Beeck EF, Polinder S, van der Velde N, van Lieshout EM, Panneman MJ, et al. Societal consequences of falls in the older population: injuries, healthcare costs, and long-term reduced quality of life. J Trauma. 2011;71:748–53.

Huguet N, Kaplan MS, Feeny D. Socioeconomic status and health-related quality of life among elderly people: Results from the Joint Canada/United States Survey of Health. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:803–10.

Mold JW, Lawler F, Roberts M. The Health Consequences of Peripheral Neurological Deficits in an Elderly Cohort: An Oklahoma Physicians Resource-Research Network Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1259–64.

Iglesias CP, Manca A, Torgerson DJ. The health-related quality of life and cost implications of falls in elderly women. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:869–78.

Davis JC, Marra CA, Najafzadeh M, Liu-Ambrose T. The independent contribution of executive functions to health related quality of life in older women. BMC Geriatr. 2010;10:1–8.

Oh B, Cho B, Choi HC, Son KY, Park SM, Chun S, et al. The influence of lower-extremity function in elderly individuals' quality of life (QOL): an analysis of the correlation between SPPB and EQ-5D. Archives of Gerontology & Geriatrics. 2014;58:278–82.

Nielsen ABS, Siersma V, Waldemar G, Waldorff FB. The predictive value of self-rated health in the presence of subjective memory complaints on permanent nursing home placement in elderly primary care patients over 4-year follow-up. Age & Ageing. 2014;43:50–7.

Eser S, Saatli G, Eser E, Baydur H, Fidaner C. The Reliability and Validity of the Turkish Version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life Instrument-Older Adults Module (WHOQOL-Old). Turk Psikiyatri Dergisi. 2010;21:1–48.

Bowling A, Stenner P. Which measure of quality of life performs best in older age? A comparison of the OPQOL, CASP-19 and WHOQOL-OLD. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:273–80.

Hakkaart-van Roijen L, Bakker TJ, Al M, van der Lee J, Duivenvoorden HJ, Ribbe MW, Huijsman R: Economic evaluation alongside a single RCT of an integrative psychotherapeutic nursing home programme. BMC Health Services Research 2013, 13.

Borowiak E, Kostka T. Influence of chronic cardiovascular disease and hospitalisation due to this disease on quality of life of community-dwelling elderly. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:1281–9.

Couzner L, Ratcliffe J, Crotty M. The relationship between quality of life, health and care transition: an empirical comparison in an older post-acute population. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2012;10:1–9.

Pintarelli VL, Perchon LF, Lorenzetti F, Toniolo Neto J, Dambros M. Elderly men's quality of life and lower urinary tract symptoms: an intricate relationship. Int Braz J Urol. 2011;37:758–65.

Perchon LF, Pintarelli VL, Bezerra E, Thiel M, Dambros M. Quality of life in elderly men with aging symptoms and lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30:515–9.

Amemiya T, Oda K, Ando M, Kawamura T, Kitagawa Y, Okawa Y, et al. Activities of daily living and quality of life of elderly patients after elective surgery for gastric and colorectal cancers. Ann Surg. 2007;246:222–8.

de Rooij SE, Govers AC, Korevaar JC, Giesbers AW, Levi M, de Jonge E. Cognitive, functional, and quality-of-life outcomes of patients aged 80 and older who survived at least 1 year after planned or unplanned surgery or medical intensive care treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:816–22.

Kaambwa B, Bryan S, Barton P, Parker H, Martin G, Hewitt G, et al. Costs and health outcomes of intermediate care: results from five UK case study sites. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2008;16:573–81.

Haines TP, Russell T, Brauer SG, Erwin S, Lane P, Urry S, et al. Effectiveness of a video-based exercise programme to reduce falls and improve health-related quality of life among older adults discharged from hospital: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23:973–85.

Elmalem S, Dumonteil N, Marcheix B, Toulza O, Vellas B, Carrie D, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation in Elderly Patients With Severe Aortic Stenosis. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2014;15:201–6.

Giles LC, Hawthorne G, Crotty M: Health-related Quality of Life among hospitalized older people awaiting residential aged care. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2009, 7.

Merlani P, Chenaud C, Mariotti N, Ricou B. Long-term outcome of elderly patients requiring intensive care admission for abdominal pathologies: survival and quality of life*. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2007;51:530–7.

Pitkala KH, Laurila JV, Strandberg TE, Kautiainen H, Sintonen H, Tilvis RS. Multicomponent Geriatric Intervention for Elderly Inpatients With Delirium: Effects on Costs and Health-Related Quality of Life. The Journals of Gerontology. 2008;63A:56–61.

Pavoni V, Gianesello L, Paparella L, Buoninsegni LT, Mori E, Gori G. Outcome and quality of life of elderly critically ill patients: An Italian prospective observational study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;54:e193–8.

Coleman SA, Cunningham CJ, Walsh JB, Coakley D, Harbison J, Casey M, et al. Outcomes among older people in a post-acute inpatient rehabilitation unit. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:1333–8.

McPhail S, Haines T. Patients undergoing subacute rehabilitation have accurate expectations of their health-related quality of life at discharge. Health & Quality of Life Outcomes. 2012;10.

Tamim H, McCusker J, Dendukuri N. Proxy reporting of quality of life using the EQ-5D. Med Care. 2002;40:1186–95.

Ekström W, Németh G, Samnegård E, Dalen N, Tidermark J. Quality of life after a subtrochanteric fracture: A prospective cohort study on 87 elderly patients. Injury. 2009;40:371–6.

Doorduijn J, Buijt I, van der Holt B, Steijaert M, Uyl-de Groot C, Sonneveld P. Self-reported quality of life in elderly patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma treated with CHOP chemotherapy. Eur J Haematol. 2005;75:116–23.

Edmans J, Bradshaw L, Franklin M, Gladman J, Conroy S. Specialist geriatric medical assessment for patients discharged from hospital acute assessment units: randomised controlled trial. Bmj-British Medical Journal. 2013;347:9.

Parlevliet JL, Hodac M, Buurman BM, Boeschoten EW, De Rooij SE: Systematic comprehensive geriatric assessment in elderly patients on chronic dialysis. European Geriatric Medicine Conference: 6th Congress of the EUGMS Dublin United Kingdom Conference Start 2010, 1.

Jones LC, Sword J, Strain WD, Ostrowski C: The correlation between patients, patient's relatives and healthcare professionals interpretation of quality of life - A prospective study. European Geriatric Medicine Conference: 10th International Congress of the European Union Geriatric Medicine Society Geriatric Medicine Crossing Borders, EUGMS 2014, 5.

McPhail S, Beller E, Haines T. Two perspectives of proxy reporting of health-related quality of life using the euroqol-5D, an investigation of agreement. Med Care. 2008;46:1140–8.

Frenkel W, Jongerius E, Van Munster BC, Mandjes-Van Uitert M, De Rooij SE: Validation of the Charlson Comorbidity Index in acutely admitted elderly patients. European Geriatric Medicine Conference: 7th Congress of the EUGMS Malaga Spain Conference Start 2011, 2.

Rasheed S, Woods RT. An investigation into the association between nutritional status and quality of life in older people admitted to hospital. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2014;27:142–51.

Winkelmayer WC, Benner JS, Glynn RJ, Schneeweiss S, Wang PS, Brookhart M, et al. Assessing Health State Utilities in Elderly Patients at Cardiovascular Risk. Med Decis Mak. 2006;26:247–54.

Tidermark J, Zethraeus N, Svensson O, Törnkvist H, Ponzer S. Femoral neck fractures in the elderly: Functional outcome and quality of life according to EuroQol. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:473–81.

Von Mackensen S, Gringeri A, Siboni SM, Mannucci PM. Health-related quality of life and psychological well-being in elderly patients with haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2012;18:345–52.

Hyttinen L, Kekalainen P, Vuorio AF, Sintonen H, Strandberg TE. Health-related quality of life in elderly patients with familial hypercholesterolemia. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2008;24:228–34.

Tidermark J, Ponzer S, Svensson O, Soderqvist A, Tornkvist H. Internal fixation compared with total hip replacement for displaced femoral neck fractures in the elderly - A randomised, controlled trial. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery-British Volume. 2003;85B:380–8.

Shmuely Y, Baumgarten M, Rovner B, Berlin J. Predictors of Improvement in Health-Related Quality of Life Among Elderly Patients With Depression. Int Psychogeriatr. 2001;13:63–73.

Wu TY, Chie WC, Kuo KL, Wong WK, Liu JP, Chiu ST, et al. Quality of life (QOL) among community dwelling older people in Taiwan measured by the CASP-19, an index to capture QOL in old age. Archives of Gerontology & Geriatrics. 2013;57:143–50.

Tidermark J, Zethraeus N, Svensson O, Tornkvist H, Ponzer S. Quality of life related to fracture displacement among elderly patients with femoral neck fractures treated with internal fixation. 2002.

Tidermark J, Bergstrom G, Svensson O, Tornkvist H, Ponzer S. Responsiveness of the EuroQol (EQ 5-D) and the SF-36 in elderly patients with displaced femoral neck fractures. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:1069–79.

Datta S, Foss AJE, Grainge MJ, Gregson RM, Zaman A, Masud T, et al. The Importance of Acuity, Stereopsis, and Contrast Sensitivity for Health-Related Quality of Life in Elderly Women with Cataracts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:1–6.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ms Nikki May who helped with the database searches and acquisition of the data. We would also like to thank Associate Professor Emily Lancsar and participants at the 36th Annual Australian Health Economics (AHES) conference in September 2014 for their helpful comments on a previous version of this paper. Ms Norma Bulamu is supported by a PhD scholarship from an Australian Research Council Linkage grant (LP110200079).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JR was responsible for study conception. NBB developed the systematic review protocol, conducted the review and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. BK and JR contributed to the development of the review protocol and revised the manuscript. All authors have seen and approved the final manuscript.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Medline search strategy. Database(s): Ovid MEDLINE(R) In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to Present. (PDF 158 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bulamu, N.B., Kaambwa, B. & Ratcliffe, J. A systematic review of instruments for measuring outcomes in economic evaluation within aged care. Health Qual Life Outcomes 13, 179 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-015-0372-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-015-0372-8