Abstract

Aim

The number of Hungarian polio patients can be estimated at approximately 3000. Polio infection is currently affecting people 56–65 years of age. The aim of the study was to reveal the quality of life of patients living with polio virus in Hungary.

Subject and methods

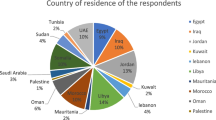

The quantitative cross-sectional study was conducted in January–April 2017 among polyomyelitis patients living in Hungary. In the non-random, targeted, expert sample selection, the target group was composed of patients infected with poliovirus (N = 268). We have excluded those who refused to sign the consent statement. Our data collection method was an SF-36 questionnaire. Using the IBM SPSS Statistics Version 22 program, descriptive and mathematical statistics (χ2-test) were calculated (p < 0.05).

Results

The mean age of the members of the examined population is 63.5 years; 68.1% were women and 31.90% were men. The majority of the respondents were infected by the polyovirus in 1956 (11.9%), 1957 (24.3%), and 1959 (19.5%). Polio patients, with the exception of two dimensions (mental health, social operation), on the scale of 100 do not reach the “average” quality of life (physical functioning 23 points, functional role 36 points, emotional role 47 points, body pain 48 points, general health 42 points, vitality 50 points, health change 31 points).

Conclusion

The quality of life of polio patients is far below the dimensions of physical function, while the difference in mental health compared to healthy people is minimal. It would be important to educate health professionals about the existing disease, to develop an effective rehabilitation method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Backround

Nowadays we hear little about poliomyelitis, the viral infectious disease that caused the greatest epidemics of the 1900s, despite its low paralytic frequency of 0.5%. Or in other words, about the Heine-Medin disease in reference to its discoverers. The peculiarity of the disease stems from the fact that it was a relatively new disease, present worldwide, mainly affecting children, and causing disability. Due to these attributes, it gained attention from scientists to bureaucrats, as the characteristics of the disease merged with the characteristics of the post-war era. While treating the polio challenged demographic was the goal, the process also improved the manufacturing technology, the theory and practice of medicine, and renewed the obsession with child propaganda and humanitarian work (Vargha 2018).

Because of efforts to curb and eradicate it, the viral infectious disease has now disappeared in more developed countries. However, a smaller number of African and Asian areas remain affected (Oberste and Lipton 2014). Based on the World Health Organization (WHO) data, the number of survivors in the world is 20 million (Koopman et al. 2011).

Epidemiological data from Hungary have been available since 1927, with three major waves of polio being highlighted: 1954, 1957, and 1959. Based on these records, 16,515 cases were detected between 1931 and 1976 (Hungarian Polio Foundation 2017).

Primarily, the polio infection caused permanent disability in children under 5 years of age through the destruction of motile neurons located in the spinal cord (Oberste and Lipton 2014).

The residual symptoms (asymmetrical flaccid paralysis, limb shortening, deformities, joint instability, contractures, loss of function, physical disability, etc.) affect the current 56–65 year-old generation, and the number of polio survivors is estimated at approximately 3000 in Hungary (based on the data officially collected from the National Health Insurance Data Management Fund between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2016, 2990 patients participated in health care based on the B91H0 BNO, of whom 2760 patients were still alive on 2017−01−01). This is approximately 0.2% of the age group concerned (based on the 2016 Population Data of the Central Statistical Office) (Central Statistics Office 2018).

Owing to the “polio immunity” of the European region and the small number of new infection, little is heard about this polio epidemic today. For the younger generation, the name of it is unknown, in the curriculum of healthcare students it is only tangential and the practitioners also have minimal knowledge of the symptoms and treatment of the poliomyelitis. Mostly, contemporaries remember the fear caused by the terrifying illness and the severe, lasting physical symptoms. However, we must not forget the fact that children–who became infected and survived at the time–are now adults with residual symptoms, presumably living in a deteriorating physical and functional state.

The global collaboration in research, prevention, and treatment of polio has been exemplary, in addition to the fact that the international exchanges of knowledge have existed from the very beginning. Of course, the actual time period itself must not be forgotten, which also significantly influenced the attitudes and financial opportunities. Regardless, the polio epidemic raised many global issues. Contemporary scientific articles and discussions highlighted the presence of polio across the continent and the serious problems raised in terms of medical care, the economy, and social stability. Furthermore, some articles highlighted the economic repercussions of the epidemic; the feasibility of the quarantine and the costs incurred in terms of their impact on trade. In addition to these, the subjugation of political independence in the fight against the epidemic was an important topic as well (Vargha 2018).

Numerous essays, in particular foreign literature describe the status and quality of life of the infected with poliomyelitis, and the assessment of the threat related to the syndromes that can appear up to decades after infection or in other words the so-called post-polio syndrome (PPS) (Werhagen and Borg 2013; Adegoke et al. 2012; Garip et al. 2017; Atwal et al. 2014; Yang et al. 2015). A retrospective study conducted in France in 2013 foresees a serious public health problem due to the deteriorating state of the survivors (Yelnik et al. 2013). PPS is an uncommonly occurring neurodegenerative, chronic, progressive disease that does not correspond to normal aging, which results from the destruction of remaining brain and spinal cord neurons due to prolonged overload (Koopman et al. 2011).

Most of the studies on quality of life report extremely poor physical but satisfactory mental functions (Garip et al. 2017; Yang et al. 2015; Jung et al. 2014). The quality of life was assessed in 2015 within the survivors of the Turkish polio population, in a study where a group of 40 healthy persons and a group of 40 people infected with polio virus were compared to each other. The participants of this latter group were distinguished by the fact of whether they were affected by post-polio syndrome (21 persons) or not (19 persons) according to the Healstead criteria. In comparison to the other polio counterparts and to the healthy group, based on the fatigue assessment, the Turkish post-polio infected generated higher, while from among the elements of the quality of life, such as physical activity, pain and energy, they generated lower results. In the examined groups, there was no significant difference in the social, emotional functions, in sleep quality, and depression (Garip et al. 2017).

On the other hand, based on a self-assessment, a group of Nigerian polio survivors even had lower mental functions. In Nigeria, the virus was still active even a few years ago; thus, in 2012 the quality of life of adolescent patients was measured in comparison to a healthy population of similar gender and age (Adegoke et al. 2012). The fifth edition of the Comprehensive Quality of Life Scale-Adolescent Questionnaire was filled out by 73 persons infected with polio viruses (mean age 14.16 ± 2.01 years) and by 73 healthy young persons (mean age 14.18 ± 2.02 years). The self-evaluation of polio survivors has presented significantly lower values for health, fertility, community, emotional and psychological factors, and overall quality of life in comparison with the healthy group. Polio reached significantly higher (p < 0.001) results in 5 out of the 7 subjective range of the Comprehensive Quality of Life Scaled Adolescent compared to the objective values.

Domestic research is limited, and most of the studies are also directed to the treatment of the residual symptoms and physical disability and the search for suitable tools for rehabilitation (Pettyán and Béresné Lutter 2010, Pettyán 2012). However, to date, there is no study on the state of health and quality of life of the polio survivors in Hungary. Therefore, the aim of this study is to fill the gap in this area.

Methodology

Our quantitative cross-sectional study was conducted between January and April 2017 among Hungarian survivors of poliomyelitis. In the non-random, targeted, expert sample selection, the target group consisted of people infected with poliovirus. We have excluded those who were not affected by polio and those who refused to sign the consent statement.

The SF-36 questionnaire was filled out by 268 people, 68.1% of the members of the study population were women, the average age of all respondents was 63.5 years (minimum 36 years, maximum 80 years, standard deviation 5.10). The majority of respondents were born in the 1940s (25 people) and 1950s (176 people), and one person was born in 1981. Participants in the study were obese based on the mean body mass index (BMI 28.28) (females 28.63, males 27.38). This result can also be explained by reduced mobility, which is supported by the high involvement of the lower limbs (monoplegia 59 people, diplegia 62 people, tetraplegia 43 people), the difficulty of moving and the use of assistive devices in large numbers (186 people). The majority of the respondents—infected with epidemiological data—were infected by the poliovirus in 1956 (11.9%), 1957 (24.3%), and 1959 (19.5%).

The questionnaires were sent to the stakeholders via e-mail, with the intervention of the Hungarian Polio Foundation. The emails contained a quality of life questionnaire, research information, and a consent statement. The response was anonymous. The Quality of Life Survey was measured with the “36-item Short Form Health Survey” (SF-36) questionnaire, which is also validated in the Hungarian version and is known for normal Hungarian values (Czimbalmos et al. 1999).

For the statistical analysis, we used the Microsoft Excel program to determine the mean and mode of each variable, to perform cluster analysis, and to analyze the relationship between the variables using the chi-square test and the Cramer association index (using the IBM SPSS Statistics Version 22 program). The level for all variables was p < 0.05. The license was granted by the Regional Scientific and Research Ethics Committee of Szombathely (39/2017).

Results

Quality of life

To examine the quality of life, we used the SF-36 questionnaire, which is a health-related quality of life study, but it also has domains that refer to other dimensions of quality of life and well-being, such as social relationships.

People infected with polio virus, with the exception of two dimensions—mental health and social function—contiunue to barely achieve “medium” quality of life on the 100 scale (Fig. 1). It is important to emphasize that the Heine-Medin disease does not cause intellectual disability, which is also supported by the fact that the vast majority of research participants (129 people) have a high school education and 65 people have certificates from higher education (college 43 people, university 18 people, academic grade 4 people). Based on responses to physical activity (physical functioning 23), for the respondents with the disease the everyday easy, moderate, or hard activities, workloads mean serious challenges, their illness strongly constrains them performing “routine tasks.” Responses to the physical role (physical role 36) have only slightly improved: based on their own perceptions, their capability is also lower in terms of work performance and other activities. Based on the results on health change (health change 31), most respondents feel that their health has deteriorated compared to last year. In social and mental health (social functioning 57, mental health 63), though the average score of the respondents exceeds 50 points, but it remains far away from the representative satisfactory level of 100 points.

Comparison with healthy

We compared the results obtained with the normal values of the healthy people from the SF-36 survey prepared by Ágnes Czimbalmos et al. (1999).

On this basis, it is a clear conclusion that the quality of life of polio patients differs significantly from the normal values of healthy people in all dimensions without exception.

Comparing the obtained values with the average values of healthy people, it is a clear conclusion that the quality of life of the people with disabilities due to poliomyelitis differs substantially and in all dimensions from the average results of the healthy people.

The differences between the two target groups are spectacular: in the dimensions of physical function and physical role, the studied disabled people have a huge lag behind their healthy counterparts. However, the difference in mental health is quite low; therefore, despite the physical disadvantages, the mental and psychological state of the polio survivors does not show any significant backlog compared to healthy people (Table 1).

The content of the phenomenon of disability in scientific studies is usually summarized in models (Johnston 1996). The relevance of this to us lies in the fact that, in addition to the medical model, the social model and the bio-social model have their place as well in the scientific approach. According to the social model, disability is not an individual trait, but a phenomenon caused by society. Not only and not primarily by making someone ill, but by stigmatizing him/her according to some concept: treating as disabled and making disabled those whose physical/mental abilities do not meet the standards set by society. In Johnstone’s formulation, “we see people with disabilities and make them see themselves as having ‘special needs.’” (Johnstone 2004).

The most important finding in this regard is that disability affects large masses, and therefore it is not an individual discriminatory manifestation but a group phenomenon (Shakespeare and Watson 2001). Thus, people with disabilities become a disadvantaged social group called “other(s).” Disadvantage in this sense does not mean health disadvantage, but rather its social affects and society’s attitude toward their special situation. Overall, it is not the health status of the individual that limits social participation, but the environmental barriers. These barriers are complex phenomenon that exist as a historically formed and constantly evolving interplay of cultural, social, political, and economic factors (Barnes 1992). According to the social model, disability cannot be treated exclusively with medical treatments aimed at normalizing the individual. In addition to the importance of medical interventions, it sets a priority for changing the environment as well. This separates the individual’s physical/mental condition from the disadvantage he or she experiences in his or her daily life (Shakespeare and Watson 2001), in education, on the labor market, in daily traffic, etc. Even if the individual’s health impairment can not be eliminated, his or her disability can be; however, this requires socio-political changes according to the model (Barnes 2000).

Patient groups, clusters

To provide a more subtle picture of the quality of life of persons affected by polio by looking at the types of patients in the eight dimensions studied, group formation and cluster analysis can be used. Clustering is a process in which the variables assigned to each element represent the dimensions along which the patients can be grouped in such a way that the members of a group are close to each variable while being away from the rest of the groups (Székelyi and Barna 2002).

The analysis was performed by hierarchical clustering (including distance-based grouping among group averages) (Tóthné 2011), and the analysis based on the eight dimensions and the health changes helped to distinguish the three types of polio patients (Fig. 2). The group with the highest number of patients was given to the patients who chose the feature of the lower tercile in all dimensions. These patients have problems with emotional, mental, and social functioning, and the physical aches and physical activities are significantly worsening their quality of life; thus, in these areas they gave 0 or near 0 values. The second group includes patients whose physical functioning and health are also low, but in their emotional, mental, and social dimensions have a significantly higher quality of life. The third group is made up of patients who have a relatively high level of quality of life except in the fields of health change and physical activities, and have close values to the healthy people. This group has the lowest cluster number.

Typical values, asymmetry

Because qualitative surveys were used, we have taken into account the size of the asymmetry indicator as well, and thus we have been given the opportunity to examine whether most respondents are above or below the average. To quantify this, Pearson’s asymmetry index was applied. A negative value of “A,” relates to right-sided asymmetry, and a positive value relates to left-sided asymmetry, and an absolute value convergence to 1 indicates an increasing asymmetry (Korpás 2004). In the questionnaire, out of 36 questions, in the case of 14 questions this asymmetry could be detected.

The average values of physical role and physical activity already reflect low quality of life, but the comparison of them to typical values highlights that in these two dimensions the majority of respondents are below normal functioning and standard of living (alternating between 0.75 and 0.93). The positive image of mental, social, and emotional factors are also confirmed by these calculations: most of the polio survivors try to focus on work and family life and their mental health is above the average (alternating between −75 and −93) (Table 2).

The overview of the situation of victims of the polio epidemic has a number of social policy implications. It raises questions such as: “How did the Hungarian state react to the domestic life problems of the victims of the polio epidemic?”; “Could politics have overridden healing?”; “What did the society do with infected who survived but did not recover?”; “How did the mobility of these children and their families develop as a result of childhood paralysis?”; etc. Dora Vargha’s recent book also points out (Vargha 2018) that although living with the disease is an individual experience, it requires health protection and disease management from a global perspective. Which also means that not only the individual but also international politics and relations have a role to play in it.

Discussion

Comparing foreign and domestic results (Table 3), we obtain a remarkably similar picture regarding the quality of life of the patients with disabilities caused by polio.

Many questionnaires are also suitable for the evaluation of non-disease-specific, general quality of life, but in most cases the use of the SF-36 questionnaire has been found in the literature.

We can see almost the same evaluation of the values we have obtained for physical functions based on a 17-year follow-up study with an average score of 21.9 (Vreede et al. 2016,), which was only slightly higher in the values of a California study (38.65 points) (Vasiliadis et al. 2002). The values of the physical role approached the average quality of life in Skough et al. (43.3) (Vreede et al. 2016). With the exception of mental health, the study of Lars Werhagen and Kristian Borg showed a worse condition for all dimensions, in which the PPS diagnosis of participants was reassessed on the basis of the criteria system (Werhagen and Borg 2013). A 2001 study, based on the evaluation of 112 survivors, reported an excellent overall health status in Canada with an average of 62.9 (Bretz et al. 2017). In Hungary, the examined people with disabilities are well below their average score of 42. Compared to the previous year, the overall change in health is characterized by the dimension of health change, which lags behind the average values of Hungarian polio survivors with only 2.1 points. The aim was to identify the factors of muscle and joint pain in post-polio syndrome in a 2002 California study. Although our domestic research did not investigate or distinguish between patients already affected by polio and post-polio syndrome, the resulting quality of life assessment is almost identical in physical function and function, mental health (75.35) and social role (72.35); however, it showed an outstanding quality of life in the US (Vasiliadis et al. 2002).

The highest average age of polio survivors at the time of the study was found in Sweden at the age of 74 on the basis of a 2016 study, which is the oldest at the time of the polio infection, based on an overview, with an average age of 10 years (Vreede et al. 2016). The majority of Hungarian polio infected are currently in their sixties (average age 63.5 years), but at the time of polio infection they had an exceptionally low average age (1.96 years).

Conclusion

Most countries’ health strategies at the beginning of the past century were largely aimed at eradicating polio, due to the high degree of global exposure and serious symptoms and residual symptoms. Owing to the eradication program launched in 1988, the disease was largely eradicated, but affected areas remained. Many of these regions, in collaboration with WHO, have carried out large-scale, complementary immunization activities and awareness-raising campaigns. In Iran, for example, the number of infections has been reduced from 50 to 0, and thus since 2001 this country can also be considered polio-free (Zahraei et al. 2009). However, many areas remain endemic, with 306 new cases reported in Pakistan in 2014 (Naqvi et al. 2017). Therefore, because of the recent illnesses and survivors of previous infections, we should not forget about the disease. It is up to health professionals to maintain and improve/maintain the quality of life of the affected patients, thus sharing important news about the disease. Hungary is also part of the polio-free zone, but the nearly 3000 survivers should remind people to not forget the dreaded disease of the past decades.

Regular assessment of the psycho-physiological parameters of the elderly (even those who are ill) is important as it helps to clarify the physical and mental states (Trojan et al. 2001). The results of the polio survivors examined in this study emphasize their persistence, their struggle, and their vitality, including their strong position regarding emotional role and mental health.

There are few groups of diseases where there is a difference in value compared to standard values. Although hopefully there will not be the need to keep up with another epidemic, professionals may still encounter many survivors during their work. “In addition to doctors, the work of highly qualified professionals is essential for effective health care and safe operation” (Betlehem and Oláh 2017; Oláh et al. 2015; Oláh et al. 2007). Therefore, it would be important to educate professionals in the medical sciences about the existing disease, to develop an effective rehabilitation method, and to help patients adapt to the often inevitable state of deterioration. In the field of health science, high-quality research is also being carried out in Hungary (Betlehem et al. 2014; Oláh et al. 2008; Oláh et al. 2012; Szabó and Gerevich 2013); therefore, through research and publicity based on relevant literature based on evidence regarding this topic, awareness-raising can be achieved.

Survivors of the polio epidemic need more attention due to their more difficult financial situation and deteriorating health. In the absence of all this, young, infected people who came from families with a modest financial background or often grew up in a public institution arrived poor to the twenty-first century. The insufficient rehabilitation opportunities and the lack of job opportunities resulted in low upward and a steep downward movement on the social ladder. Nonetheless, based on the results obtained, the polio survivors involved in the research do not lag behind in their social functioning and mental health in comparison to healthy people, i.e., they do not feel the social deficits advertised by the social model. This raises further questions and indicates the need for further, forward-looking research on the topic.

Limitations of the research

However, when comparing the two target groups examined, the conclusions should be treated with caution. On the one hand, surveys were conducted during two different periods of time, normal values of healthy people could change in time; on the other hand, the computational methods of the survey for healthy people have not been published, and thus there may be methodological differences. It should also be borne in mind that the Healthy Survey does not only include the results of the 56–65 age group, who naturally have poorer quality of life results.

References

Adegoke BOA, Oni AA, Gbiri CA, Akosile CO (2012) Paralytic poliomyelitis: quality of life of adolescent survivors. Hong Kong Physiother J 30:93–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hkpj.2012.07.002

Atwal A, Spiliotopoulou G, Coleman C, Harding K, Quirke C, Smith N, Osseiran Z, Plastow N, Wilson L (2014) Polio survivors’ perceptions of the meaning of quality of life and strategies used to promote participation in everyday activities. Health Expect 18:715–726. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12152

Barnes C (1992) Institutional discrimination against disabled people and the campaign for anti- discrimination legislation. Crit Soc Policy 34(12):5–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/026101839201203401

Barnes C (2000) A working social model? Disability, work and disability politics in the 21st century. Crit Soc Policy 4(20):441–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/026101830002000402

Betlehem J, Oláh A (2017) The possibility of renewing care in Hungary [Az ápolás megújulásának lehetősége hazánkban]. IME 16(9):5–15 [in Hungarian]

Betlehem J, Horvath A, Jeges S et al (2014) How healthy are ambulance personnel in Central Europe? Eval Health Prof 37(3):394–406

Bretz É, Kóbor-Nyakas DÉ, Bretz KJ, Hrehuss N, Radék Z, Cs N (2017) Correlations of psycho-physiological parameters influencing the physical fitness of aged women. Acta Physiol Hung 101:471–478. https://doi.org/10.1556/APhysiol.101.2014.005

Central Statistics Office [Központi Statisztikai Hivatal] (2018) www.ksh.hu, http://www.ksh.hu/docs/hun/xstadat/xstadat_eves/i_wdsd009.html. Accessed 2 Feb 2018. [in Hungarian]

Czimbalmos Á, Nagy ZS, Varga Z, Husztik P (1999) Patient satisfaction survey [Páciens megelégedettségi vizsgálat]. Népegészségügy (1):4–19 [in Hungarian]

Garip Y, Eser F, Bodur H, Baskan B, Sivas F, Yilmaz O (2017) Health related quality of life in Turkish poliosurvivors: impact of post-polio on the healthrelated quality of life in terms of functional status, severity of pain, fatigue, and social, and emotional functioning. Rev Bras Reumatol 57(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbre.2014.12.006

Gonzalez H, Khademi M, Borg K, Olsson T (2012) Intravenous immunoglobulin treatment of the post-polio syndrome: sustained effects on quality of life variables and cytokine expression after one year follow up. J Neuroinflammation 9(167). https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-2094-9-167

Hungarian Polio Foundation (2017) http://polio.hu/2016/03/12/tajekoztato-a-gyermekbenulasos-betegek-torteneterol-es-helyzeterol/. Accessed 21 Jan 2017

Johnstone CJ (2004) Disability and identity: personal constructions and formalized support. Disability Studies Quarterly 24(4):52

Johnston M (1996) Models of disability. Physiotherapy: Theory and Practice 12(3):131–141

Jung TD, Broman L, Stibrant-Sunnerhagen K, Gonzalez H, Borg K (2014) Quality of life in Swedish patients with post-polio syndrome with a focus on age and sex. Int J Rehabil Res 37:173–179. https://doi.org/10.1097/MRR.0000000000000052

Koopman FS, Beelen A, Gilhus NE, de Visser M, Nollet F (2011) Treatment for postpolio syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 18(5):CD007818. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007818.pub3

Korpás A (2004) General statistics I. [Általános statisztika I.] Nemzeti Tankönyvkiadó, Budapest [in Hungarian]

Naqvi AA, Naqvi SBS, Yazdani N et al (2017) Understanding the dynamics of poliomyelitis spread in Pakistan. Iran J Public Health 46(7):997–998

Oberste MS, Lipton HL (2014) Global polio perspective. Neurology 82:1831–1832. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000000426

Oláh A, Máté O, Betlehem J et al (2015) The international practice and acceptation concept on Hungary of the advanced practice nurse (APN) training on the MSc level. Nővér 28(2):1–44

Oláh A, Betlehem J, Kriszbacher I et al (2007) Re: the clinical nursing competences and their complexity in Belgian general hospitals. J Adv Nurs 58(3):301–302

Oláh A, Betlehem J, Müller A et al (2008) Possible application of animal models for the long-term investigation of shift work of healthcare professionals. J Perinatal Neonatal Nurs 22(3):175–176

Oláh A, Gy K, Gál N et al (2012) The comparison of two minimal invasive surgeries, the tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) and the transobturator tape (TOT) in terms of efficiency and the complications. South Eastern Eur Health Sci J 2(2):82–87

Pettyán I, Béresné Lutter M (2010) Rehabilitation of Heine-Medin patients [Heine-Medin-betegek rehabilitációja]. Rehabilitáció 20(2):108–113 [in Hungarian]

Pettyán I (2012) Post-polio syndrome [Posztpolió szindróma]. Orvostovábbképző szemle 19(7–8):78–80 [in Hungarian]

Shakespeare T, Watson N (2001) The social model of disability: an outdated ideology? Res Soc Sci Disabil 2:9–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1479-3547(01)80018-X

Szabó J, Gerevich J (2013) Alcohol dependency, recovery, and social words. J Appl Soc Psychol 43:806–810

Székelyi M, Barna I (2002) Survival kit for SPSS [Túlélőkészlet az SPSS-hez]. Typotex Kiadó, Budapest [in Hungarian]

Tóthné PL (2011) Fundamentals of research methodology in mathematics [a kutatásmódszertan matematika alapjai]. Eszterházy Károly Főiskola, Eger [in Hungarian]

Trojan DA, Collet J, Pollak MN, Shapiro S, Jubelt B, Miller RG, Agre JC, Munsat TL, Hollander D, Tandan R, Robinson A, Finch L, Ducruet T, Cashman NR (2001) Serum insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) does not correlate positively with isometric strength, fatigue, and quality of life in post-polio syndrome. J Neurol Sci 182(2):107–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-510x(00)00459-7

Yang EZ, Lee SY, Kim K, Jung SH, Jang SN, Han SJ, Kim WH, Lim JY (2015) Factors associated with reduced quality of life in polio survivors in Korea. PLoS One 10(6):e0130448. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130448

Yelnik AP, Andriantsifanetra C, Bradai N, Sportouch P, Beaudreuil J, Dizien O (2013) Poliomyelitis sequels in France and the clinical and social needs of survivors: a retrospective study of 200 patients. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine 56:542–550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2013.08.001

Vargha D (2018) Polio across the Iron curtain Hungary's cold war with an epidemic. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p 22. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108355421

Vasiliadis HM, Collet JP, Shapiro S, Venturini A, Trojan DA (2002) Predictive factors and correlates for pain in postpoliomyelitis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 83:1109–1115. https://doi.org/10.1053/apmr.2002.33727

Vreede KS, Broman S, Borg K (2016) Long-term follow-up of patients wit prior polio over a 17-year period. J Rehabil Med 48:359–364. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-2068

Werhagen L, Borg K (2013) Impact of pain on quality of life in patients with post-polio. J Rehabil Med 45:161–163. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-1096

Zahraei S, Sadrizadeh B, Gouya M (2009) Eradication of poliomyelitis in Iran, a historical perspective. Iran J Public Health 38:124–126

Funding

Open Access funding provided by University of Pécs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EVM carried out the research work (preparation of the research plan, patient recruitment, contact) and summarized the results, MJ assisted in compiling the communication, AP worked on the statistical background.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The license was granted by the Regional Scientific and Research Ethics Committee of Szombathely (39/2017).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all patients included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Miszory, E.V., Járomi, M. & Pakai, A. Quality of life in Hungarian polio survivors. J Public Health (Berl.) 31, 285–293 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01459-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01459-w