Abstract

Aims

Healthcare utilization is a major challenge for low- and middle-income countries, especially for the publicly funded facilities. The study has tried to explore the women’s opinion behind the non-utilization of public healthcare facilities in India.

Subjects and methods

This was a cross-sectional study using nationally representative samples of 351,625 women of reproductive age (15–49 years) from the 29 States and seven Union Territories. Indian National Family Health Surveys NFHS-4 (2015–2016) was the data source. The respondents were asked why the members of their households do not utilize public healthcare facilities when members of their households are sick. They have options to respond either ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Five reasons for non-utilization of public healthcare were asked: (i) ‘there is no nearby facility’; (ii) ‘facility timing is not convenient’; (iii) ‘health personnel are often absent’; (iv) ‘waiting time is too long’; and (v) ‘poor quality of care’.

Results

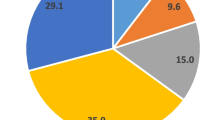

The majority of the women in India (88%) said that their family members did not use public healthcare facilities. The reasons behind this were 'no nearby facilities' (42.4%), 'inconvenient facility timing' (29.6%), 'poor quality of care' (52.3%), 'health personnel often absent' (16.8%) and 'long waiting time' (39.9%).

Conclusions

importantly, during the last 10 years, the utilization of public health care facilities has dropped significantly, which should be taken seriously as the Indian Parliament has been placing emphasis on equity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Equity in health and healthcare has been an important aspect of health policy in India, by improving the access to quality of care by the poor and disadvantaged sections of society (National Health Policy India 2002, 2017). Various policy documents demonstrate that health systems in most of the states in India have aimed to eliminate the barriers of healthcare utilization, and promise to achieve a stage where every person, irrespective of their socio-economic background will receive equal treatment for equal need of medical care. But there are gaps in healthcare utilization in India, and a systematic analysis is needed to identify what causes the barriers to healthcare utilization, and what can be done from a policy-making perspective to address the problems (Dalal and Dawad 2009; ICMR 2017).

Various studies have been conducted to assess the rates of utilization of the public and private sector health services. The utilization rates in public health service systems range from 10 to 42% (Dalal and Dawad 2009, ICMR 2017, IIPS 2017, Chandra and Patwardhan 2018). According to the national health policy, major thrusts of the plans have been provided to improve the healthcare facilities in rural areas (National Health Policy India 2017). However, there remain concerns about the utilization of those services. In addition, the reality on the ground with regard to non-utilization of services is not always the same in every area; it varies from one place to another (ICMR 2017; IIPS 2017; Chandra and Patwardhan 2018). Not much work has been performed so far to explore the reasons behind the non-utilization of the public healthcare facilities (Dalal and Dawad 2009). The present study, using a nationally representative survey, has tried to explore the opinion of women which lies behind the non-utilization of public healthcare facilities in India.

Methods

The study used secondary data from NFHS-4, conducted in India during 2015–16. NFHS-4 is a nationally representative survey with a sample of 628,892 residential households. A total of 351,625 women of reproductive age (94.5% response rate) were interviewed from all over India covering the 29 States and seven Union Territories.

The 2011 Census served as the sampling frame for NFHS-4. Using the 2011 Census data, a sampling frame of all census enumeration blocks (CEBs) in urban areas and all villages in rural areas was compiled. In total, 28,586 primary sampling units (PSUs) consisting of CEBs and villages for NFHS-4 were surveyed.The sample for NFHS-4 was a stratified sample selected in two stages from the sampling frame. The survey followed a uniform sample design procedure using probability proportional to population size (PPS). Data collection was conducted by 789 field teams consisting of one field supervisor, four trained interviewers (three female and one male), and two health investigators. Each team had one driver. A more detailed description of the sampling procedure is available in the NFHS-4 final report (ICMR 2017).

Dependent variables

The respondents were asked why the members of their households do not utilize public healthcare facilities when members of their households are sick. They had options to respond either ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Five reasons for non-utilization of public healthcare were asked: (i) ‘there is no nearby facility’; (ii) ‘facility timing is not convenient’; (iii) ‘health personnel are often absent’; (iv) ‘waiting time is too long’; and (v) ‘poor quality of care’.

Independent variables

Demographic information such as age (15–19 years, 20–24 years, 25–29 years, 30–34 years, 35–39 years, 40–44 years and 45–49 years), place of residence (rural/urban), religion (Hindu, Muslim, and others), economic status, exposure to bank account, below poverty line (BPL) card, and health insurance were used. Religion includes Hindu, Muslim, Christian, Sikh, Buddhist/Neo-Buddhist, Jain, and others. However, in the current study we merged Christian, Sikh, Buddhist/Neo-Buddhist, Jain, and others, and created a new option ‘Other religion’.

Housing materials were considered in three categories; kancha (made of mud or soil), semi-pucca (made of partly cement and partly soil), and pucca (made of cement). Economic status was measured by wealth index, introduced by Rutstein and Johnson (2004), previously used in India and including any item that may reflect economic status (Dalal and Dawad 2009, Rutstein and Johnson 2004). It was constructed to include almost all household assets and utility services, including country-specific items. The wealth index ranged from ‘poorest’ to ‘richest’ (poorest, poorer, middle, richer, and richest).

The study identified the various services respondents went to when seeking health care. The respondents were asked to respond with Yes/No for using the following healthcare facilities: postnatal care, family planning, disease prevention, medical treatment for self, medical treatment for child, medical treatment for other person, medical growth monitoring of child, health check-up, medical treatment of pregnancy or any other services.

Ethical issue

The current study has used secondary data and hence does not need any ethical permission. However, as per the survey protocol, ethical approval was sought from the Institutional Ethical Review Board (Ref. no./IRB/NFHS-4/01_1/2015) of the IIPS, Mumbai, India.

Statistical analyses

Cross-tabulation was used to assess the association between the dependent and independent variables. Significant levels were tested using the chi-squared test. Logistic regression was used for assessing the association between dependent and independent variables. The magnitude and direction of associations were expressed by odds ratios (OR). A significance level of p < 0.05 was used for analysis.

Results

The majority of the women in India (88%) said that their family members did not use public healthcare facilities. The reasons behind this were: no nearby facilities (42.4%), inconvenient facility timing (29.6%), poor quality of care (52.3%), health personnel often absent (16.8%), and long waiting times (39.9%).

Among the 351,625 women respondents, almost 70% lived in rural areas; 49% had secondary, and 12% had higher secondary education.

Demographics

Table 1 summarises participants’ demographics according to opinion category with regard to non-utilization of public healthcare facilities. Table 2 shows participants’ opinion category with regard to non-utilization of public healthcare facilities according to which service they are seeking.

Women from different age groups ranging from 15 years to 49 years complained equally about no nearby public health facilities, inconvenient facility timings, poor quality of care, etc.

Women in urban areas were 0.719 times less likely than those in rural areas to indicate that there were no nearby healthcare facilities, 0.850 times less likely to complain about inconvenient facility timings, 0.953 times less likely to refer to poor quality of care, but 1.2 times more likely to reveal issues related to long waiting times than those living in the rural areas (Table 3).

Among the 93,323 women who had no education, only 16.2% complained about absent health personnel in the facility, and 51% of them complained about poor quality of care in the facilities. Women with no education were approximately 1.02 times more likely to talk about poor quality of care than the women with higher education. Also among those who had primary education (45,672), 16.8% agreed about frequent absent of health personnel in the facilities.

Women who had secondary education (171,855) were equally likely to talk about inconvenient facility timing, and again equally likely to complain about the length of waiting times and poor quality of care as those who had higher education.

Economic status

The poorest population were 1.05 times more likely to express their feelings about the lack of nearby facilities, and 1.251 more likely to complain about poor quality of care in the facilities than those belonging to the richest quintile.

People belonging to the poorest section of the society complained more about services such as no nearby facilities (52.7%), inconvenient facility timings (23.4%), absent health personnel (13.9%), longer waiting time (32.7%), and poor quality of care (51.8%). The trend of grievance decreased accordingly as the wealth quintile increased for each indicators.

Service seeking

As reported women who did not use public facilities for the treatment of children were more likely to agree about the poor quality of care in the public health facilities than those who went for treatment in these facilities.

Women who did not seek post-natal care delivery were 1.1 times more likely to complain about no nearby facilities, and 1.19 times more likely to say that health personnel in public facilities were often absent.

Women who did not seek self-medical treatment from public health facilities were less likely to agree that there were no nearby facilities (OR 0.971, CI.0.951–0.992).

Women who did not look for treatment of another person in public facilities were 1.1 times more likely to agree about the poor quality of care in these facilities.

Women who did not go for health checkups in public facilities were less likely to agree that there were no nearby facilities (OR – 0.991), but equally likely to tell about inconvenient facility timings, and equally likely to agree about absent health personnel.

Discussion

The study has provided a scope to compare the health care utilization scenario over a period of 10 years, between 2005–06 and 2015–16. During 2005–06, 58% women and during 2015–16, 88% women in India said that their family members did not use public healthcare facilities. During the last 10 years, considering previous studies, women’s complaints have increased as reasons for non-utilization of health care facilities are demonstrating a worsened scenario: no nearby facilities (2005–06: 27%, 2015–16: 42.4%), inconvenient facility timing (2005–06: 8.8%, 2016–16: 29.6%), poor quality of care (2005–06: 31.6%, 2015–16: 52.3%), health personnel often absent (2005–06: 4.9%, 2015–16:16.8%) and longer waiting time (2005–06: 16.7%, 2015–16: 39.9%) (Dalal and Dawad 2009). Therefore, the current paper has a strong policy implication for the Indian policy makers, as women of reproductive age are getting more dissatisfied, even for the basic healthcare services, with public healthcare facilities in India. This could explain why private healthcare facilities are booming in India, resulting in a ‘medical-poverty-trap’, especially for the poorer socioeconomic strata (Dalal and Dawad 2009; Dalal and Rahman 2008; Mojumdar 2018). Also, the scenario shows that lower utilization of public healthcare facilities even for the basic services may result in a higher healthcare burden for poor families, showing widened health inequity in India.

Irrespective of the ability to pay, people in India increasingly seek private healthcare even for minor illnesses such as cold, fever, and diarrhea. Private healthcare in India, however, is not only expensive but also suffers severely from lack of trained and skilled manpower as compared to the public sector (Dalal and Rahman 2008). The study points out some important aspects on the associations among non-utilization of public health facilities, in terms of demographics and people's pattern of service-seeking.

This study is among a few which have tried to explore the inefficient supply of services on the basis of demands from the people who are actually the recipient of those services. The study analyses data from a nationally representative sample, and the results should be considered in any reform of the public healthcare system.

Access to public healthcare facilities is an important issue in terms of developing public health facilities. Researchers have found that in rural areas people frequently become dependent on unqualified medical practitioners because they do not have any other choices available — in many areas due to the geographical spread of the villages, such situations arise when no qualified doctors are present to treat acute illness episodes (Dalal and Dawad, 2009, Mojumdar 2018). Thus, access to health care is very significantly asymmetric between rural and urban India. While urban residents have a choice between public or private providers, the rural residents face far fewer choices (Majumder 2006). Thus, there is a difference in terms of the health-seeking behavior of people in rural and urban areas; but again, research has shown if a well-functioned public facility is available, a trend to visit the public facility develops in the respective population. Person-centeredness, comprehensiveness and integration, and continuity of care, with a regular point of entry into the health system, can build an enduring relationship of trust between people and their healthcare providers (Majumder 2006). Here also, it can be observed that people both from rural (42%) and urban (43%) areas expressed their grievances in regard to no available public facilities nearby. More than half of the population from both rural and urban areas questioned the poor quality of care in the public facilities, leading to non-utilization of those services. It can be assumed that in the absence of a well-functioning health system people have moved to other services for seeking treatment. Now irrespective of the ability to pay, people in India increasingly seek private health care even for minor illnesses like cold, fever, and diarrhea (Barik and Thorat 2015). For minor illnesses it might happen that due to non-availability of doctors or inconvenient facility timings, etc., people from rural areas are also going to private facilities. It can be assumed as the public health facilities run in the daytime and most urban as well as women from the rural areas remain engaged in different activities either in home or outside during this period, it becomes quite difficult for them to access those services. It can be recommended that a revised timing of the public health facilities could address the problem to some extent.

It has been found that 42.4% of women reported that due to non-availability of public facilities nearby, they did not go for any post-natal care services, while 39.7% of women who went for post-natal care services also complained about non-availability of nearby public facilities. People from the poorest wealth quintile (52.7%) complained more about no nearby facilities than people belonging to the richest wealth quintile (36.7%). The trend was observed in cases of complaints about inconvenient facility timing, absence of health personnel, long waiting times, and poor quality of care; people from the poorer wealth quintile complained more about the above-mentioned issues than people belonging to the richer section. This is very usual, as poor people with no alternatives available tend to focus more on public facilities; hence, it might be possible that the grievances are more from poor people than the rich. However, several studies have shown that there is a marked reluctance to use free facilities even among the poorest sections in Indian society. For example, a study of health and healthcare among scheduled castes showed that 38% sought private medical help when their children became ill compared with 28% for government health facilities (Nair et al. 2004).

Also, 39.8% of the women complained about long waiting time at public facilities as a reason for non-utilization of the services such as post-natal care where as 41.3% of women who were actually receiving the post-natal services expressed their dissatisfaction about long waiting time in the public facilities. Research has shown that waiting times have been linked to inefficiencies in healthcare delivery, prolonged patient suffering, and dissatisfaction among the public, and this has become an important policy issue in many countries (Das et al. 2008). It might be possible that longer waiting times lead to non-utilization of public health facilities in both rural and urban areas.

The data show that respondent’s education level and economic status also play a significant role in the awareness and decision-making process of the family, with regard to using the public healthcare facilities as well. In the previous study of non-utilization of public healthcare facilities, examining the reasons through a national study of women in India while comparing the data of NFHS 3, it was demonstrated that respondents’ education, economic status, and standard of living emerged as significant predictors for non-utilization of public healthcare facilities (Dalal and Dawad 2009). Higher education and economic status indicate greater dissatisfaction with public healthcare facilities. It has been observed that people who have bank accounts (resulting from an already generated awareness about financial security) complained more about long waiting times (40.7%) and poor quality of care (52.2%) with regard to public health services than those who do not have any access to bank account facilities. It might be said that a certain level of awareness of economic status enhances people’s way of looking at things, and thus greater dissatisfaction comes from the privileged section of society than from their less privileged counterparts. In particular, people from rural areas with the double burden of little access and fewer staff in the healthcare facilities complained more about these issues than people living in urban areas. It is recommended that consideration should be given to equal distribution and improved quality of care in the public health facilities to regain the faith of people in the health system.

The data also reflected that in terms of demanding public health services such as medical treatment during pregnancy, treatment for children or health check-ups for self, or other issues are hugely affected by inconvenient facility timing and poor quality of care. In developing countries, the poor quality of care in public health facilities has been aggravated as one moves from urban to rural areas — unfortunately, the causes of this disturbing reality are illnesses that can be treated and deaths that can be prevented by simple interventions, but for which inappropriate health systems structures have constituted a stumbling block (Hooda 2017). These create increased dissatisfaction towards the services.

Public healthcare is very much affected by irregularity or absence of staff, quality of care available, etc., in the facilities. Studies have found that the perception of poor quality of care may reduce the utilization of health services among women irrespective of their economic status (Barik and Thorat 2015, Prinja et al. 2012). Also, the World Health Report 2006 identified scarcity of qualified staff in public facilities as a key issue of deteriorating health-seeking behaviour in developing countries (WHO 2006). From the available facts, the present study recommends increased investment in public healthcare facilities; improved quality of care and regularity of medical staffing levels should be ensured for a better outcome of services. To improve maternal and child health issues, policies should be revised to engage more staff, redistribute available resources, and add many more to address issues related to longer waiting time in the facilities, etc.

The present study has some limitations. In addition, due to resource constraints the study examined public healthcare problems using few dependent variables. In acknowledgement of the many other problems existing in the system, the inclusion of other ‘problem’ variables (such as maternal healthcare) is recommended for future studies. The results of this study can, however, be used to influence policy-making in India because it used representative samples from all states.

A study in India in 2012 showed that around 60% of all households and around half of BPL households made out-of-pocket payments for health care, resulting in a deepening of poverty, especially among the poorest. However, the deepening of poverty among the poor due to healthcare payments was substantially larger for the urban poor compared with their rural counterparts (Das et al. 2008). The greater vulnerability of the urban poor could be the result of more expensive private care relative to rural areas (Das et al. 1996, Kreindler 2010). In the absence of affordable, efficient, and effective public healthcare facilities, the poor population from the rural areas are becoming dependent on unqualified medical practitioners, leading in many cases to a prolongation of their period of morbidity (Kreindler 2010; Oladipo 2014). With the findings of the above study in terms of an inefficient and aloof health system, poor people in India are likely to experience —and sometimes already are experiencing — catastrophic expenditure on health care, resulting in them facing medical poverty traps and extended morbidity (Rani et al. 2008; Renu and Rao 2012; WHO 2008).

Conclusion

The study concludes that redistribution and re-formulation of public healthcare facility are necessary to address many issues of better public health care utilization, especially if the Indian health ministry really wants to achieve the Indian National Health Policy 2017. In addition, user-friendly opening times in the facilities, improved quality of care, and availability of health personnel in the facilities would help to build a trust-based relationship between service seeker and service provider. A good relationship on both sides with improved quality of care develops the health-seeking behavior of people, leading to greater utilization of the public health facilities. Most importantly, during the last 10 years, the utilization of public healthcare facilities has dropped significantly, which should be taken seriously as the Indian Parliament has been placing emphasis on equity.

Availability of data and materials

Data are publicly available upon permision from the authority. If anyone is interested to obtain data they can visit the following website. http://rchiips.org/NFHS/data1.shtml

References

Barik D, Thorat A (2015) Issues of unequal access to public health in India. Front Public Health 3:245

Chandra S, Patwardhan K (2018) Allopathic, Ayush and informal medical practitioners in rural India — a prescription for change. J Ayurveda Integr Med 9(2):143–150

Dalal K, Rahman A (2008) Out-of-pocket payments for unintentional injuries: a study in rural Bangladesh. Int J Inj Control Saf Promot 8:1–7

Dalal K, Dawad S (2009) Non-utilization of public health care facilities: examining the reasons through a national study of women in India. Rural Remote Health 9(3):1178

Das GM, Chen L, Krishnan TN (1996) Health, poverty and development in India. Oxford University Press, Delhi

Das J, Hammer J, Leonard K (2008) The quality of medical advice in low-income countries. J Econ Perspect 22(2):93–114

Hooda SK (2017) Out-of-pocket payments for healthcare in India, who have affected the most and why? J Health Manag 9(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972063416682535

Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), Public Health Foundation of India, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (2017) India: health of the nation’s states — the India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) (2017) National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015–16: India. IIPS, Mumbai

Kreindler SA (2010) Policy strategies to reduce waits for elective care: a synthesis of international evidence. Br Med Bull 95:7–32

Majumder A (2006) Utilization of health care in North Bengal: a study of health seeking patterns in an interdisciplinary framework. J Social Sci 13(1):43–51

Mojumdar SK (2018) Determinants of health service utilization by urban households in IndiaA multivariate analysis of NSS case-level data. J Health Manag. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972063418763642

Nair VM, Thankappan KR, Vasan RS, Sarma PS (2004) Community utilization of sub-centres in primary health care - an analysis of determinants in Kerala. Int J Publ Health 48(1):17–20

National Health Policy, India (2002). https://www.nhp.gov.in/sites/default/files/pdf/NationaL_Health_Pollicy.pdf

National Health Policy India (2017). http://164.100.158.44/index1.php?lang=1&level=1&sublinkid=6471&lid=4270

Oladipo JA (2014) Utilization of health care services in rural and urban areas: a determinant factor in planning and managing health care delivery systems. Afr Health Sci 14(2):322–333

Prinja S, Kaur M, Kumar R (2012) Universal health insurance in India: ensuring equity, efficiency, and quality. Indian J Community Med 37(3):142–149

Rani M, Bonu S, Harvey S (2008) Differentials in the quality of antenatal care in India. Int J Qual Health Care 20(1):62–71

Renu S, Rao KD (2012) Insured yet vulnerable: out-of-pocket payments and India’s poor. Health Policy Plan 27(3):213–221

Rutstein SO, Johnson K (2004) The DHS wealth index. DHS Comparative Reports no. 6. ORC Macro, Calverton MD

WHO (2006) The World Health Report — working together with health. WHO, Geneva

WHO (2008) The World Health Report — primary health care:now more than ever. WHO, Geneva

Funding

Open access funding provided by Mid Sweden University. The authors have used secondary data and received their salary from their respective employers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KD conceptualized the idea, analyzed the data and led the study. TB prepared the first draft. AD and SD conducted the literature and current work review. KD critically reviewed the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest is declared.

Ethical approval

The current study has used secondary data and hence does not need any ethical permission. However, as per the survey protocol, ethical approval was sought from the Institutional Ethical Review Board (Ref. no./IRB/NFHS-4/01_1/2015) of the IIPS, Mumbai, India.

Consent for publication

The authors have used secondary data where the individual identity was missing. Therefore consent for publication is not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bagchi, T., Das, A., Dawad, S. et al. Non-utilization of public healthcare facilities during sickness: a national study in India. J Public Health (Berl.) 30, 943–951 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01363-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01363-3