Abstract

Tuta absoluta is a devastating invasive pest worldwide, causing severe damage to the global tomato industry. It has been recorded recently in the northwestern border areas of China, posing a significant threat to tomato production. It was presumed that the region's winter-related low temperatures would avert the alien species from successfully overwintering. In this study, the supercooling capacity and low-temperature tolerance of this pest were examined under laboratory conditions and its overwintering potential in Xinjiang was estimated. The results showed that the lowest supercooling point was recorded in the adult stage (− 19.47 °C), while the highest (− 18.11 °C) was recorded in the pupal stage. The supercooling points of pupae and adults were not influenced by gender. The Ltemp50 and Ltemp90 of female and male adults were the lowest when exposed to cold for 2 h. However, when the duration of exposure extended from 4 to 10 h, the Ltemp50 and Ltemp90 of female and male pupae were the lowest. Comparison of the lowest Ltemp50 and Ltemp90 with temperatures in January indicated that T. absoluta might not be able to overwinter in most of the northern and central regions of Xinjiang. However, in the southern regions, the extremely low temperature was higher than the Ltemp90, suggesting that T. absoluta has a higher overwintering potential in these regions. These results form a basis for predicting the dispersal potential and possible geographic range of this pest in Xinjiang. In addition, our findings provide guidance for the control of this pest by reducing overwintering shelters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Key message

-

Tuta absoluta adults could tolerate short-term extremely low temperature stress, while pupae could tolerate long-term low-temperature stress.

-

The cold temperatures in northern and central Xinjiang have the potential to kill overwintering populations, while in southern parts, T. absoluta has the potential to successfully overwinter.

-

The results form a basis for predicting the dispersal potential and possible geographic range of this pest in Xinjiang, and provide guidance for the control of this pest by reducing overwintering shelters.

Introduction

The South American tomato pinworm, Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) is one of the most devastating pests of solanaceous crops threatening the global tomato industry and has become an invasive pest around the world (Biondi et al. 2018; Desneux et al. 2010). This pest could cause severe damage through larval mining and feeding of leaves, stems and tomato fruits, which could result in up to 80–100% yield loss in tomato crops (Desneux et al. 2010). This pest is native to South America, and was first recorded in Spain in 2006, thereafter rapidly spreading throughout other European countries and the Mediterranean Basin (Desneux et al. 2011). In 2008, T. absoluta was first reported in Africa and has now been reported in 41 of the 54 African countries (Mansour et al. 2018). Since the first report in Turkey in 2009, this pest started invading Asia and now has been recorded in most Asian countries (Han et al. 2019a), including many countries on the northwestern and southwestern border of China, e.g., Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, India, Nepal etc. (Campos et al. 2017; Saidov et al. 2018; Sankarganesh et al. 2017; Uulu et al. 2017). So far, it has been recorded in more than 90 countries and regions worldwide (Campos et al. 2017; Desneux et al. 2011; Uulu et al. 2017; Verheggen and Fontus 2019). Seven out of the ten largest world tomato producers, namely India, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, Italy, Spain and Brazil have already recorded infestation by this pest (Campos et al. 2017; Desneux et al. 2011). China is the largest tomato producer in the world, accounting for 32.6% in total tomato production and 21.2% in planting area (FAOSTAT 2017). Recently, T. absoluta has been found in the border area of Xinjiang (Zhang et al. 2019), which is the largest tomato production province in China. The wide distribution of this pest in the future may pose a significant threat to China’s tomato production.

Temperature plays an important role in the life history, behavior, fitness and abundance of insects, as well as the successful colonization and dispersal of invasive insects (Renault et al. 2018; Umeda and Paine 2019; Wallner 1987). Extreme temperature could act as a barrier that limit dispersal and potential invasive range of non-native insects (Marini et al. 2011; Rassati et al. 2016; Umeda and Paine 2019). Likewise, temperature significantly affects the population dynamics and invasion success of T. absoluta (Karadjova et al. 2013; Tonnang et al. 2015), although the pest can diapause (Campos et al. 2020). Based on its thermal requirement and stress factors, the potential distribution of T. absoluta could be predicted using models, e.g., CLIMEX (Santana et al. 2019). The spatio-temporal spread of this pest could also be predicted using more comprehensive models that account for biological, ecological and human factors, e.g., the multi-pathway propagation model (McNitt et al. 2019). Nevertheless, as an invasive species, T. absoluta has an extremely strong adaptability to changing environments. It usually establishes and outbreaks in warm areas or seasons, but could also establish in cold regions or seasons in protected fields. It has been reported that this species can survive temperatures slightly below zero degrees for a short period (Potting et al. 2013). For instance, half a given number of T. absoluta could stay alive for several weeks when exposed to 0 °C or 5 °C (Van Damme et al. 2015). When exposed to a stressful low temperature for 2 h, the lower lethal temperatures for adults ranged from − 1 to − 12 °C. This resulted into a 0–100% mortality, suggesting a high cold tolerance of this pest (Machekano et al. 2018).

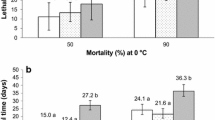

It was assumed that the low temperatures during winter in newly invaded areas would prevent invasive species from successful overwintering (Kahrer et al. 2019). Xinjiang is one of the regions in China that suffer very harsh winter, with the lowest temperatures recorded between − 10 and − 30 °C (Hu 2014). Consequently, understanding the cold tolerance of T. absoluta is crucial for evaluating its dispersal potential in this province. Supercooling point (SCP), the temperature at which body fluids spontaneously freezes, is a commonly used index for evaluating cold tolerance in insects (Andreadis and Athanassiou 2017). The SCP represents the lowest lethal temperature for freeze-intolerant individuals. Along with the SCP, measurement of insect mortality at low temperature is another insect’s cold hardiness characteristics. Supercooling point could be directly affected by several factors, including physiology, behavior, life stages and sex (Bastola and Davis 2018; Hemmati et al. 2014). The survival of insects under low-temperature stress also varies with their life stages, temperature and duration of exposure (Matsukura et al. 2014; Nedved et al. 1998). Van Damme et al. (2015) reported on the SCPs and low-temperature survival of T. absoluta in Belgium, in Western Europe. The results from this study showed that the SCPs of larvae, pupae and adults were − 18.2, − 16.7 and − 17.8 °C, respectively (Van Damme et al. 2015). The 50% lethal time (Lt50) at 0 °C of larvae, pupae and adults was 11.1, 13.3 and 17.9 days, respectively, and the 90% lethal time (Lt90) of the three stages was 23.4, 25.7 and 30.3 days, respectively, while at 5 °C, the Lt50 of larvae, pupae and adults was 15.0, 12.4 and 27.2 days, respectively, and the Lt90 of the three stages was 24.1, 21.6 and 36.3 days, respectively (Van Damme et al. 2015). However, the survival of T. absoluta under temperatures below 0 °C has not been studied. In another study, the maximum survival times (Kaplan–Meier, Lt99.99) of T. absoluta pupae were determined at − 10, − 8, − 6, − 4, − 2, 0, + 2 and + 4 °C, but not for other life stages (Kahrer et al. 2019).

In this present study, the supercooling points of T. absoluta at different life stages were determined. Further, its survival rate at different life stages under different low temperatures (− 15 to 5 °C) and durations of exposure (2–10 h) as well as its 50% lethal temperature (Ltemp50) and 90% lethal temperature (Ltemp90) were estimated in the laboratory. Finally, the overwintering potential of this invasive pest in different regions in Xinjiang was assessed by comparing the extremely low temperatures of these regions with the 50% and 90% lethal temperature. The purpose of this study was to determine whether T. absoluta could effectively survive at low temperatures in the invaded areas. Information on the supercooling temperature of T. absoluta may help to develop appropriate strategies for its control in tomato production areas.

Materials and methods

Insects

Larvae of T. absoluta were collected from a tomato field in Anbanbage Village, Chabuchal Xibo Autonomous County, Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (81° 12′ 11.01″ E, 43° 49′ 40.00″ N), in July 2018. The insects were reared on potted tomato plants (Variety “Money maker”) kept in cages.

Supercooling point determination

The supercooling points (SCPs) of different life stages of T. absoluta (larvae, pupae and adults) were determined. Third instar larvae were directly collected from the colony. Pupae were obtained by separately rearing larvae in Petri dishes until pupation. Adults were obtained by rearing pupae until eclosion. The influence of gender on the SCPs was assessed using female and male pupae, as well as female and male adults. Gender of pupae and adults was determined under the microscope following the features described by Genç (2016).

The SCPs of individuals at different stages and gender were measured as described by Hou et al. (2009a). Individual of a given life stage was placed in l ml pipette tip and fixed with cotton wool. A copper constant thermocouple was attached to the surface of each individual and linked to an automatic temperature recorder (Jiangsu Senyi economic development Co. Ltd, Jiangsu, China). The thermocouple, together with the insect, was placed into a freezer (DW-40L188, Qingdao Medical and Laboratory Products Co., Ltd, Shandong) that was cooled gradually at a rate of 1 °C/min. The SCP was determined as the temperature recorded by the thermocouple just before an exothermic event caused by the release of the latent heat of crystallization (Costanzo et al. 1997). Totally 38 third instar larvae, 72 pupae (35 females and 37 males) and 41 adults (17 females and 24 males) were tested.

Effect of low temperature and exposure duration on the survival of T. absoluta

Third instar larvae, female pupae, male pupae, female adults, and male adults were exposed to 5, 0, − 5, − 10 and − 15 °C for 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 h. The combination of each temperature and duration of exposure was treated as one treatment. There were 5 replicates for each treatment, with 10 individuals in each replicate. After exposure, individuals were transferred into a climate chamber at 25 ± 1 °C under a LD 16: 8 h photocycle and 65–75% relative humidity and new tomato leaves were provided. Survival of larvae and adults were checked after 24 h, and the survival rate was calculated. Survival of pupae was checked everyday for eclosion until 10 days after treatment. The 50% lethal temperature (Ltemp50) and 90% lethal temperature (Ltemp90) of different stages at different durations of exposure were calculated. The relationship of survival with duration of exposure and temperature was regressed.

Overwintering potential of T. absoluta in different regions in Xinjiang

January is the coldest month in Xinjiang, with the lowest mean daily minimum temperature and extremely low temperature all year round (Table 1). To estimate whether T. absoluta could overwinter in Xinjiang, the extremely low temperature as well as the mean daily minimum temperature in January in 2017, 2018 and 2019 from 12 regions of Xinjiang (including Urumchi, Atltay, Tacheng, Yining, Changji, Kumul, Turpan, Korla, Hetian, Aksu, Kashgar and Artux) were compared with the Ltemp50 and Ltemp90 calculated above.

Data analyses

All data analyses were performed in SPSS (SPSS Inc., 2007, Chicago, IL). SCPs were compared among different life stages using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (P < 0.05). Means were compared using LSD multiple comparison test. SCPs of different gender were compared by Student’s t test (P < 0.05).

The 50% lethal temperature (Ltemp50) and 90% lethal temperature (Ltemp90) at different durations of exposure were calculated using Probit analysis.

The relationship of survival with duration of exposure and temperature was regressed by the following logistic equation in OriginPro:

where S is survival rate, t is exposure duration (h), T is temperature exposed (°C), and a, b and c are constant parameters (Nedved et al. 1998). c is an estimate of the upper limit of cold injury zone (ULCIZ). The ratio −a/b is the sum of injurious temperature (SIT, degree/h) (Wang et al. 2012).

Results

The effect of life stages and gender on the supercooling points of T. absoluta

SCPs were significantly different among the different life stages of T. absoluta (F2, 148 = 3.078, P = 0.049; Fig. 1). The lowest SCP among the different life stages was recorded in adults (− 19.47 °C), while the highest (− 18.11 °C) was recorded in the pupal stage (Fig. 1). The SCP of larvae (− 18.42 °C) was not significantly different from pupae (− 18.11 °C) (Fig. 1). The SCPs were not influenced by gender (Fig. 2a, b), as there were no differences between female and male pupae (t = 1.594, df = 70, P = 0.116), as well as between female and male adults (t = − 1.172, df = 39, P = 0.248).

The Ltemp50 and Ltemp90 of different life stages of T. absoluta at different durations of exposure

The Ltemp50 and Ltemp90 of larvae exposed for 2 h was − 9.43 °C and − 22.95 °C, respectively (Fig. 3a, b). The Ltemp50 and Ltemp90 of larvae increased sharply when the duration of exposure extended to 4 h (Ltemp50: − 4.75 °C; Ltemp90: − 14.05 °C) (Fig. 3a, b). When they were exposed for 6, 8 and 10 h, the Ltemp50 and Ltemp90 of larvae remained stable (Ltemp50: ranged from − 3.29 to − 3.53 °C; Ltemp90: ranged from − 10.57 to − 11.37 °C) (Fig. 3a, b).

The same patterns were also observed for the Ltemp50 and Ltemp90 of female and male adults. When female adults were exposed for 2 h, the Ltemp50 and Ltemp90 were − 13.47 and − 33.44 °C, respectively (Fig. 3a, b). However, when they were exposed for 4, 6, 8 and 10 h, the Ltemp50 and Ltemp90 significantly increased. Ltemp50 ranged from − 3.60 to − 4.31 °C, and Ltemp90 ranged from − 8.41 to − 10.04 °C (Fig. 3a, b). When male adults were exposed for 2 h, the Ltemp50 and Ltemp90 were − 10.87 and − 36.86 °C, respectively (Fig. 3a, b). However, when they were exposed for 4, 6, 8 and 10 h, the Ltemp50 and Ltemp90 significantly increased, ranging from − 2.76 to − 3.38 °C and from − 10.62 to − 11.88 °C, respectively (Fig. 3a, b).

By contrast, the Ltemp50 and Ltemp90 of female and male pupae stayed relatively stable, with slight increase when the exposure duration was extended (Fig. 3a, b). For female pupae, the Ltemp50 ranged from − 9.93 to − 8.92 °C, and the Ltemp90 ranged from − 17.56 to − 15.96 °C (Fig. 3a, b). For male pupae, the Ltemp50 ranged from − 9.79 to − 6.40 °C, and the Ltemp90 ranged from − 20.81 to − 15.51 °C (Fig. 3a, b).

The lowest Ltemp50 and Ltemp90 were recorded in female and male adults when they were exposed for 2 h. However, the lowest Ltemp50 and Ltemp90 were recorded in female and male pupae when they were exposed to cold for 4–10 h.

Relationship of temperature and cold exposure duration with T. absoluta survival at different life stages

The survival curves of larvae, female pupae, male pupae, female adults and male adults successfully fitted a logistic equation (P < 0.0001) (Table 2, Fig. 4). Their adjusted R2 ranged from 0.696 to 0.849. The female and male pupae had lower ULCIZ (− 9.90 and − 7.39 °C) compared with larvae, female adults and male adults (− 4.70, − 3.79 and − 4.94 °C, respectively). The SIT of larvae, female pupae, male pupae, female adults and male adults were − 8.98, − 2.56, − 8.88, − 10.72 and − 4.66 h/degree, respectively.

Overwintering potential of T. absoluta in different regions from Xinjiang

Because the lowest Ltemp50 and Ltemp90 were recorded in female and male pupae, they were selected to estimate the overwintering potential.

The extremely low temperatures in 6 regions from the north and central part of Xinjiang (Urumchi, Altay, Tacheng, Yining, Changji and Kumul) in 2017, 2018 and 2019 were lower than the Ltemp90 (Fig. 5a). This suggested that over 90% of T. absoluta could be killed by extremely low temperatures in these regions. However, for the rest of the regions, mostly from the southern part of Xinjiang, the extremely low temperatures were higher than the Ltemp90 but lower than the Ltemp50 (Fig. 5a), suggesting that more than half of a given population of T. absoluta could not survive during the winter.

Except for Altay, the average daily minimum temperatures in January from 11 regions were above the Ltemp90 but lower than the Ltemp50 (Fig. 5b). However, exposure for 4 h to the lowest Ltemp50 (− 9.61 °C) as used here could result in a 50% mortality. Continuous exposure to low temperatures throughout one month could cause even more than 50% mortality for overwintering T. absoluta.

Discussion

The results in our study showed that the SCP of pupae (− 18.11 °C) was the highest among different life stages, which is consistent with the results obtained from the study on the Belgian population (Van Damme et al. 2015). However, the SCPs of larvae, pupae and adults (− 18.42, − 18.11 and − 19.47 °C) in our study were slightly lower than those done on the Belgian population, which were − 18.20, − 16.70 and − 17.80 °C for larvae, pupae and adults, respectively. This might result from cold acclimation effects. It has been reported that acclimation at low temperatures could improve the supercooling ability of insects (Andreadis et al. 2005, 2014; Zheng et al. 2011). The Belgian populations, which were mainly from the Mediterranean area where this pest first entered Europe (Desneux et al. 2010), did not experience very harsh winter. However, the population in our study might be from the Central Asian region bordering Xinjiang. Before entering Xinjiang, this pest may have already experienced cold acclimation, which resulted in the development of its greater supercooling ability. The low SCPs found in T. absoluta from both Xinjiang and Belgium might suggest that this pest has diapause potential. However, no reproductive diapause under short-day conditions has been confirmed in the Belgian population (Van Damme et al. 2015). Therefore, the diapause responses of T. absoluta in Xinjiang should be further investigated.

In many previous published reports, the difference in SCPs among life stages has also been found in several lepidopterous species (Aryal and Jung 2018; Hemmati et al. 2014; Park et al. 2017; Zheng et al. 2011). However, the lowest supercooling points reported varied with different life stages. For example, in some species, The lowest SCP was recorded in the egg or larval stage compared to later stages (Aryal and Jung 2018; Park et al. 2017). However, in T. absoluta, the lowest supercooling point was recorded in adults and the highest in pupae. Supercooling point is affected by several factors, including feeding status, contact with moisture, water content, body size and accumulation of cryoprotectants (Sømme 1982; Xu et al. 2011). The accumulation of cryoprotectants including glycerol and other polyols is closely related to cold tolerance in insects (Danks 2000; Williams et al. 2002). However, water content and body size had complicated effects on supercooling points as it showed different patterns among species (Atapour and Moharramipour 2009; Hou et al. 2009b; Xu et al. 2011). Further studies are needed to explore the possible reasons for the differences in supercooling point among different stages in T. absoluta.

Besides the SCPs, the survival of T. absoluta at different life stages also showed a significant difference. During exposure to short-time low temperature (2 h), female and male adults recorded extremely low Ltemp90, below − 30 °C. This is consistent with the lowest SCP in adults stage reported in our study as well as in a previous study (Van Damme et al. 2015). These results indicated that female and male adults could tolerate short-term extremely low temperature stress. However, the lethal temperature of adults predicted in our study was much lower than that reported by Machekano et al. (2018), who reported of 100% mortality when adults were exposed to − 12 °C for 2 h. This may be attributed to their use of a geographically different population from Southern Africa (Machekano et al. 2018). When the exposure time was extended, the Ltemp90 of female and male adults increased to around − 10 °C and changed slightly when the exposure time was further extended. A similar pattern was also found for the Ltemp90 of larvae. When the exposure duration extended to 4 h or longer, the Ltemp90 of larvae and adults was further above their supercooling points. This suggested that the cold tolerance of larvae and adults of T. absoluta should be classified as a chill-tolerant strategy (Andreadis and Athanassiou 2017; Bale 1996). By contrast, the Ltemp90 of pupae was relatively stable at different durations of exposure to low temperature, all slightly above the supercooling point of pupae (− 18.11 °C), which suggested that the cold tolerance of T. absoluta pupae was freeze intolerance or avoidance (Andreadis and Athanassiou 2017). When the exposure duration was longer than 4 h, the pupal stage recorded the lowest Ltemp90 compared to the other life stages, indicating a higher cold tolerance capacity of pupae during long-term low temperature stress. This is consistent with the results reported by Kahrer et al. (2019), who found that T. absoluta pupae were the most frost-resistant compared to other developmental stages of the species at − 4 °C. However, results from Van Damme et al. (2015) showed that adults had the highest cold tolerance compared to larvae and pupae at 5 °C, but the survival was not significantly influenced by its developmental stage at 0 °C.

Comparison of the lowest Ltemp50 and Ltemp90 with temperatures in January indicated that T. absoluta could not overwinter in most of the northern and central regions of Xinjiang. The extremely low temperature could kill more than 90% of overwintering individuals. In addition, the minimum temperature in January in these regions was continuously low. Continuous cold shocks could cause even more mortality (Rivers 2008). However, in the southern regions, the extremely low temperature was higher than the Ltemp90, suggesting that T. absoluta has higher overwintering potential in these regions. However, overwinter of pest in the field might be affected by many other factors, including humidity, soil temperature and planting patterns. In the field, T. absoluta usually overwinters under the surface litter or in the soil, where temperatures are higher compared to air temperatures (Guo et al. 2019), and likewise the soil and residual host plants in early winter which are usually covered by snow (Han et al. 2018). Greenhouses or plastic houses also provide shelters for overwintering individuals (Han et al. 2019a). Consequently, the survival of overwintering individuals should be higher than what we estimated. This speculation is corroborated by the presence of this pest in Belgium in February (Van Damme et al. 2015) and high population density of this pest in open fields in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan (Han et al. 2018). Since T. absoluta has a high reproductive capacity, even 10% of surviving individuals have the potential to cause severe damage in the next growing season (Van Damme et al. 2015). Studies on the survival of T. absoluta under field conditions are needed to further understand the overwintering and dispersal potential in Xinjiang.

Due to the high invasion capacity of T. absoluta, preparations must be made for the potential spread of this pest in Xinjiang or across China in the near future (Han et al. 2019a, 2018). Currently, various control methods have been used to manage T. absoluta in its native range and invaded countries. Chemical control is the primary tool to manage T. absoluta in newly invaded areas, which could prevent further spread of this pest. However, due to the reported resistance in T. absoluta to many chemical classes of insecticides (Guedes et al. 2019), IPM strategy including other environmentally friendly methods should be adopted. Pheromone based mass trapping and mating disruption have proven to be effective control measures in areas with low population densities (Aksoy and Kovanci 2016; Cocco et al. 2013). The proper use of biological control agents (e.g., predator Nesidiocoris tenuis, trichogrammatid wasps, Bacillus thuringiensis) could also help suppress T. absoluta populations (Arnó et al. 2018; Chailleux et al. 2012; González-Cabrera et al. 2011; Mirhosseini et al. 2019). The use of inherent or enhanced resistance in plants, such as resistant host plant cultivars (Cherif et al. 2019), botanical extracts (Soares et al. 2019), transgenic resistant plants (Selale et al. 2017) and enhanced plant resistance via manipulation of soil abiotic factors (e.g., bottom-up effects) (Blazheyski et al. 2018; Han et al. 2019b), is another promising management strategy for reducing damage by this pest. Novel management technologies, such as RNA interference (RNAi) (Majidiani et al. 2019) and sterile insect technique (SIT) (Cagnotti et al. 2012, 2016; Paladino et al. 2016), have been explored recently, which could be considered in the further management of T. absoluta.

In conclusion, this study is the first to investigate the cold tolerance of T. absoluta in Xinjiang in China. Our results showed that the population we used in this study had extremely high cold tolerance capacity. Adults could tolerate short-term extremely low temperature, while pupae were more tolerable to long-term exposure of low-temperature stress. The cold temperatures in northern and central Xinjiang have the potential to kill overwintering populations of T. absoluta, while in southern parts, T. absoluta has the potential to successfully overwinter. This information forms a basis for predicting the dispersal potential and possible geographic range of this pest in Xinjiang. Our findings also provide guidance for the control of this pest. In northern and central Xinjiang, where extreme low temperature could kill overwintering T. absoluta, reducing overwintering shelters could be an effective agronomic control method. For example, removing surface litter after growing season and opening the empty greenhouses and plastic tubes during winter could increase the exposure of overwintering individuals to cold temperature and thus reduce the survival of overwintering population.

Author contributions

XL, YL and WG conceived and designed research. XL, DL and LW conducted experiments. ZZ, JH and JZ analyzed data. XL and MH wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

References

Aksoy E, Kovanci OB (2016) Mass trapping low-density populations of Tuta absoluta with various types of traps in field-grown tomatoes. J Plant Dis Protect 123:51–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41348-016-0003-6

Andreadis SS, Athanassiou CG (2017) A review of insect cold hardiness and its potential in stored product insect control. Crop Prot 91:93–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2016.08.013

Andreadis SS, Milonas PG, Savopoulou-Soultani M (2005) Cold hardiness of diapausing and non-diapausing pupae of the European grapevine moth, Lobesia botrana. Entomol Exp Appl 117:113–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1570-7458.2005.00337.x

Andreadis SS, Spanoudis CG, Athanassiou CG, Savopoulou-Soultani M (2014) Factors influencing supercooling capacity of the koinobiont endoparasitoid Venturia canescens (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae). Pest Manag Sci 70:814–818. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.3619

Arnó J, Oveja MF, Gabarra R (2018) Selection of flowering plants to enhance the biological control of Tuta absoluta using parasitoids. Biol Control 122:41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2018.03.016

Aryal S, Jung C (2018) Cold tolerance characteristics of Korean population of potato tuber moth, Phthorimaea operculella (Zeller), (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Entomol Res 48:300–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-5967.12297

Atapour M, Moharramipour S (2009) Changes of cold hardiness, supercooling capacity, and major cryoprotectants in overwintering larvae of Chilo suppressalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Environ Entomol 38:260–265. https://doi.org/10.1603/022.038.0132

Bale JS (1996) Insect cold hardiness: a matter of life and death. Eur J Entomol 93:369–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02765804

Bastola A, Davis JA (2018) Cold tolerance and supercooling capacity of the redbanded stink bug (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). Environ Entomol 47:133–139. https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvx177

Biondi A, Guedes RNC, Wan FH, Desneux N (2018) Ecology, worldwide spread, and management of the invasive South American tomato pinworm, Tuta absoluta: past, present, and future. Annu Rev Entomol 63:239–258. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-031616-034933

Blazheyski S, Kalaitzaki AP, Tsagkarakis AE (2018) Impact of nitrogen and potassium fertilization regimes on the biology of the tomato leaf miner Tuta absoluta. Entomol Gen 37:157–174. https://doi.org/10.1127/entomologia/2018/0321

Cagnotti CL, Andorno AV, Hernandez CM, Paladino LC et al (2016) Inherited sterility in Tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae): pest population suppression and potential for combined use with a generalist predator. Fla Entomol 99:87–94. https://doi.org/10.1653/024.099.sp112

Cagnotti CL, Viscarret MM, Riquelme MB, Botto EN et al (2012) Effects of X-rays on Tuta absoluta for use in inherited sterility programmes. J Pest Sci 85:413–421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-012-0455-9

Campos MR, Béarez P, Amiens-Desneux E, Ponti L et al (2020) Thermal biology of Tuta absoluta: demographic parameters and facultative diapause. J Pest Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-020-01286-8

Campos MR, Biondi A, Adiga A, Guedes RNC et al (2017) From the Western Palaearctic region to beyond: Tuta absoluta 10 years after invading Europe. J Pest Sci 90:787–796. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-017-0867-7

Chailleux A, Desneux N, Seguret J, Do Thi Khanh H et al (2012) Assessing European egg parasitoids as a mean of controlling the invasive South American tomato pinworm Tuta absoluta. PLoS ONE 7:e48068. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0048068

Cherif A, Attia-Barhoumi S, Mansour R, Zappala L et al (2019) Elucidating key biological parameters of Tuta absoluta on different host plants and under various temperature and relative humidity regimes. Entomol Gen 39:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1127/entomologia/2019/0685

Cocco A, Deliperi S, Delrio G (2013) Control of Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) in greenhouse tomato crops using the mating disruption technique. J Appl Entomol 137:16–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0418.2012.01735.x

Costanzo JP, Moore JB, Lee RE Jr, Kaufman PE et al (1997) Influence of soil hydric parameters on the winter cold hardiness of a burrowing beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say). J Comp Physiol B 167:169–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s003600050061

Danks HV (2000) Dehydration in dormant insects. J Insect Physiol 46:837–852. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-1910(99)00204-8

Desneux N, Luna MG, Guillemaud T, Urbaneja A (2011) The invasive South American tomato pinworm, Tuta absoluta, continues to spread in Afro-Eurasia and beyond: the new threat to tomato world production. J Pest Sci 84:403–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-011-0398-6

Desneux N, Wajnberg E, Wyckhuys KAG, Burgio G et al (2010) Biological invasion of European tomato crops by Tuta absoluta: ecology, geographic expansion and prospects for biological control. J Pest Sci 83:197–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-010-0321-6

FAO Statistical Database (FAOSTAT) (2017) ICTUpdate, FAO. https://www.fao.org/faostat. Accessed 17 Aug 2019

Genç H (2016) The tomato leafminer, Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae): pupal key characters for sexing individuals. Turk J Zool 40:801–805. https://doi.org/10.3906/zoo-1510-59

González-Cabrera J, Mollá O, Montón H, Urbaneja A (2011) Efficacy of Bacillus thuringiensis (Berliner) in controlling the tomato borer, Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Biocontrol 56:71–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-010-9310-1

Guedes RNC, Roditakis E, Campos MR, Haddi K et al (2019) Insecticide resistance in the tomato pinworm Tuta absoluta: patterns, spread, mechanisms, management and outlook. J Pest Sci 92:1329–1342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-019-01086-9

Guo Q, Li Q, Qu J, Wang G (2019) Variation of soil temperature in the desert-oasis ecotone. Arid Zone Res 36:809–815. https://doi.org/10.13866/j.azr.2019.04.03

Han P, Bayram Y, Shaltiel-Harpaz L, Sohrabi F et al (2019) Tuta absoluta continues to disperse in Asia: damage, ongoing management and future challenges. J Pest Sci 92:1317–1327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-018-1062-1

Han P, Desneux N, Becker C, Larbat R et al (2019) Bottom-up effects of irrigation, fertilization and plant resistance on Tuta absoluta: implications for Integrated Pest Management. J Pest Sci 92:1359–1370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-018-1066-x

Han P, Zhang Y-n, Lu Z-z, Wang S et al (2018) Are we ready for the invasion of Tuta absoluta? Unanswered key questions for elaborating an integrated pest management package in Xinjiang, China. Entomol Gen 38:113–125. https://doi.org/10.1127/entomologia/2018/0739

Hemmati C, Moharramipour S, Talebi AA (2014) Effects of cold acclimation, cooling rate and heat stress on cold tolerance of the potato tuber moth Phthorimaea operculella (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Eur J Entomol 111:487–494. https://doi.org/10.14411/eje.2014.063

Hou M, Han Y, Lin W (2009) Influence of soil moisture on supercooling capacity and associated physiological parameters of overwintering larvae of rice stem borer. Entomol Sci 12:155–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-8298.2009.00316.x

Hou M, Lin W, Han Y (2009) Seasonal changes in supercooling points and glycerol content in overwintering larvae of the asiatic rice borer from rice and water-oat plants. Environ Entomol 38:1182–1188. https://doi.org/10.1603/022.038.0427

Hu BB (2014) Inter-annual and inter-decadal variations of extreme minimum temperature in China. Ocean University of China, Qingdao

Kahrer A, Moyses A, Hochfellner L, Tiefenbrunner W et al (2019) Modelling time-varying low-temperature-induced mortality rates for pupae of Tuta absoluta (Gelechiidae, Lepidoptera). J Appl Entomol 143:1143–1153. https://doi.org/10.1111/jen.12693

Karadjova O, Ilieva Z, Krumov V, Petrova E et al (2013) Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae): potential for entry, establishment and spread in Bulgaria. Bulg J Agric Sci 19:563–571

Machekano H, Mutamiswa R, Nyamukondiwa C (2018) Evidence of rapid spread and establishment of Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) in semi-arid Botswana. Agri Food Secur 7:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-018-0201-5

Majidiani S, PourAbad RF, Laudani F, Campolo O et al (2019) RNAi in Tuta absoluta management: effects of injection and root delivery of dsRNAs. J Pest Sci 92:1409–1419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-019-01097-6

Mansour R, Brevault T, Chailleux A, Cherif A et al (2018) Occurrence, biology, natural enemies and management of Tuta absoluta in Africa. Entomol Gen 38:83–112. https://doi.org/10.1127/entomologia/2018/0749

Marini L, Haack RA, Rabaglia RJ, Petrucco Toffolo E et al (2011) Exploring associations between international trade and environmental factors with establishment patterns of exotic Scolytinae. Biol Invasions 13:2275–2288. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-011-0039-2

Matsukura K, Izumi Y, Kumashiro S, Matsumura M (2014) Cold tolerance of the maize orange leafhopper, Cicadulina bipunctata. J Insect Physiol 67:114–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinsphys.2014.05.021

McNitt J, Chungbaek YY, Mortveit H, Marathe M et al (2019) Assessing the multi-pathway threat from an invasive agricultural pest: Tuta absoluta in Asia. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 286:20191159. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2019.1159

Mirhosseini MA, Fathipour Y, Holst N, Soufbaf M et al (2019) An egg parasitoid interferes with biological control of tomato leafminer by augmentation of Nesidiocoris tenuis (Hemiptera: Miridae). Biol Control 133:34–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2019.02.009

Nedved O, Lavy D, Verhoef HA (1998) Modelling the time–temperature relationship in cold injury and effect of high-temperature interruptions on survival in a chill-sensitive collembolan. Funct Ecol 12:816–824. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2435.1998.00250.x

Paladino LZC, Ferrari ME, Lauría JP, Cagnotti CL et al (2016) The effect of X-rays on cytological traits of Tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Fla Entomol 99(43–53):11. https://doi.org/10.1653/024.099.sp107

Park Y, Kim Y, Park G-W, Lee J-O et al (2017) Supercooling capacity along with up-regulation of glycerol content in an overwintering butterfly, Parnassius bremeri. J Asia Pac Entomol 20:949–954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aspen.2017.06.014

Potting R, van der Gaag D, Loomans A, van der Straten M et al (2013) Tuta absoluta, tomato leaf miner moth or South American tomato moth-Pest risk analysis for Tuta absoluta. Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality, Plant Protection Service of the Netherlands, Utrecht

Rassati D, Faccoli M, Battisti A, Marini L (2016) Habitat and climatic preferences drive invasions of non-native ambrosia beetles in deciduous temperate forests. Biol Invasions 18:2809–2821. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-016-1172-8

Renault D, Laparie M, McCauley SJ, Bonte D (2018) Environmental adaptations, ecological filtering, and dispersal central to insect invasions. Annu Rev Entomol 63:345–368. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-020117-043315

Rivers D (2008) Classification in cold tolerance. In: Capinera JL (ed) Encyclopedia of Entomology, vol 4, 2nd edn. Springer, Berlin, pp 998–999

Sømme L (1982) Supercooling and winter survival in terrestrial arthropods. Comp Biochem Phys A Phys 73:519–543. https://doi.org/10.1016/0300-9629(82)90260-2

Saidov N, Ramasamy S, Mavlyanova R, Qurbonov Z (2018) First report of invasive South American tomato leaf miner Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) in Tajikistan. Fla Entomol 101:147–149. https://doi.org/10.1653/024.101.0129

Sankarganesh E, Firake DM, Sharma B, Verma VK et al (2017) Invasion of the South American tomato pinworm, Tuta absoluta, in northeastern India: a new challenge and biosecurity concerns. Entomol Gen 36:335–345. https://doi.org/10.1127/entomologia/2017/0489

Santana PA, Kumar L, Da Silva RS, Picanço MC (2019) Global geographic distribution of Tuta absoluta as affected by climate change. J Pest Sci 92:1373–1385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-018-1057-y

Selale H, Dağlı F, Mutlu N, Doğanlar S et al (2017) Cry1Ac-mediated resistance to tomato leaf miner (Tuta absoluta) in tomato. Plant Cell, Tissue Organ Cult 131:65–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11240-017-1262-z

Soares MA, Campos MR, Passos LC, Carvalho GA et al (2019) Botanical insecticide and natural enemies: a potential combination for pest management against Tuta absoluta. J Pest Sci 92:1433–1443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-018-01074-5

Tonnang HEZ, Mohamed SF, Khamis F, Ekesi S (2015) Identification and risk assessment for worldwide invasion and spread of Tuta absoluta with a focus on Sub-Saharan Africa: implications for phytosanitary measures and management. PLoS ONE 10:e0135283. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135283

Umeda C, Paine T (2019) Temperature can limit the invasion range of the ambrosia beetle Euwallacea nr. fornicatus. Agric For Entomol 21:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/afe.12297

Uulu TE, Ulusoy MR, Calskan AF (2017) First record of tomato leafminer Tuta absoluta Meyrick (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) in Kyrgyzstan. Bull OEPP/EPPO Bull 47:285–287. https://doi.org/10.1111/epp.12390

Van Damme V, Berkvens N, Moerkens R, Berckmoes E et al (2015) Overwintering potential of the invasive leafminer Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) as a pest in greenhouse tomato production in Western Europe. J Pest Sci 88:533–541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-014-0636-9

Verheggen F, Fontus RB (2019) First record of Tuta absoluta in Haiti. Entomol Gen 38:349–353. https://doi.org/10.1127/entomologia/2019/0778

Wallner WE (1987) Factors affecting insect population dynamics: differences between outbreak and non-outbreak species. Annu Rev Entomol 32:317–340. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.en.32.010187.001533

Wang H, Ma Z, Cui F, Wang X et al (2012) Parental phase status affects the cold hardiness of progeny eggs in locusts. Funct Ecol 26:379–389. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2011.01927.x

Williams JB, Shorthouse JD, Lee RE (2002) Extreme resistance to desiccation and microclimate-related differences in cold-hardiness of gall wasps (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae) overwintering on roses in southern Canada. J Exp Biol 205:2115–2124. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1483067

Xu S, Wang M-L, Ding N, Ma W-H et al (2011) Relationships between body weight of overwintering larvae and supercooling capacity; diapause intensity and post-diapause reproductive potential in Chilo suppressalis Walker. J Insect Physiol 57:653–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinsphys.2010.12.010

Zhang G, Ma D, Liu W, Wang Y et al (2019) The arrival of Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae), in China. J Biosafety 28:200–203. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.2095-1787.2019.03.007

Zheng X, Cheng W, Wang X, Lei C (2011) Enhancement of supercooling capacity and survival by cold acclimation, rapid cold and heat hardening in Spodoptera exigua. Cryobiology 63:164–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cryobiol.2011.07.005

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFD0200400); the Key R&D Program of Zhejiang Province (2018C02032); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31570387; 31901885); and the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LQ18C140003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants and/or animals (other than insects) performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Communicated by Nicolas Desneux.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Xw., Li, D., Zhang, Zj. et al. Supercooling capacity and cold tolerance of the South American tomato pinworm, Tuta absoluta, a newly invaded pest in China. J Pest Sci 94, 845–858 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-020-01301-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-020-01301-y