Abstract

Objective

This study aims to explore the relationship between plaque surface morphology and neovascularization using a high temporal and spatial resolution 4D contrast-enhanced MRI/MRA sequence.

Materials and methods

Twenty one patients with either recent symptoms or a carotid artery stenosis ≥40% were recruited in this study. Plaque surface morphology and luminal stenosis were determined from the arterial phase MRA images. Carotid neovascularization was evaluated by a previously validated pharmacokinetic (PK) modeling approach. K trans (transfer constant) and v p (partial plasma volume) were calculated in both the adventitia and plaque.

Results

Image acquisition and analysis was successfully performed in 28 arteries. Mean luminal stenosis was 44% (range 11–82%). Both adventitial and plaque K trans in ulcerated/irregular plaques were significantly higher than smooth plaques (0.079 ± 0.018 vs. 0.064 ± 0.011 min−1, p = 0.02; 0.065 ± 0.013 vs. 0.055 ± 0.010 min−1, p = 0.03, respectively). Positive correlations between adventitial K trans and v p against stenosis were observed (r = 0.44, p = 0.02; r = 0.55, p = 0.01, respectively).

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the feasibility of using a single sequence to acquire both high resolution 4D CE-MRA and DCE-MRI to evaluate both plaque surface morphology and function. The results demonstrate significant relationships between lumen surface morphology and neovascularization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Stroke is one of the leading causes of death and disability worldwide [1] with ischemic strokes accounting for 90% of the total reported cases [2]. Twenty percent of ischemic strokes are attributed to carotid atherosclerosis [3]. Carotid luminal stenosis measured by ultrasound plays an important role in screening high risk patients and is the standard criteria for surgical referral [4]. Whilst only patients with severe stenosis (≥70%) have shown a benefit from carotid endarterectomy (CEA), patients with moderate stenosis (<70%) have only shown marginal beneficial effects from surgical treatment [5, 6]. There is an increasing recognition that other factors, such as plaque surface morphology, may have higher predictive value in moderately stenosed plaques [7].

The appearance on X-ray angiography of plaque surface irregularity, or ulceration, has been correlated with increased risk of ischemic stroke [8]. This correlation applies for both moderate and severe stenosis [8]. Carotid ulceration is found to be more common in patients with downstream micro emboli [9]. Ulceration has also been associated with high risk factors including plaque rupture, intraplaque hemorrhage and a large lipid-rich necrotic core (LRNC) [10], indicating this is a sensitive marker of plaque instability [10] and risk of stroke [8, 11, 12]. Noninvasive imaging modalities offer high accuracy for ulcer detection as well as stenosis measurement [13–15]. Among different imaging modalities, contrast-enhanced MR angiography provides high resolution imaging allowing visualization of plaque ulceration [13, 16, 17].

In this study we have applied a 4D sequence [18] which acquires data suitable for contrast enhanced (CE) MRA and dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE)-MRI processing. DCE-MRI has been demonstrated as a non-invasive method to quantify the extent of neovasculature within carotid plaques with high accuracy and reproducibility [19, 20]. Previous studies using DCE-MRI have shown that plaque neovascularization is closely associated with high risk features, such as inflammation [21], and is related to ischemic events [22]. In this study, we investigated the correlation between plaque surface morphology and neovascularization.

Materials and methods

Experimental methods

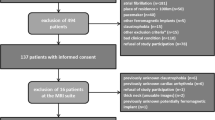

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the local ethics committee and written informed consent was obtained. Twenty one patients who had a carotid stenosis of at least 40% on Duplex ultrasound using NASCET criteria [23] were recruited in total. Ten were symptomatic (nine males, mean age 72 years, range 59–86 years) with a recent history (less than 6 months) of transient ischemic attack (TIA), and 11 were asymptomatic (seven males, mean age 78 years, range 68–87 years).

MRI protocol

Imaging was performed on a 3T system (MR750, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA), using a 4 channel phased-array neck coil (PACC, MachNet, Roden, The Netherlands). The time-resolved imaging of contrast kinetics (TRICKS) method [18] was performed to obtain 4D CE-MRI with the acquisition resolution of 0.6 × 0.6 × 1.4 mm3 and the images were interpolated into 0.3 × 0.3 × 0.7 mm3 for the DCE analysis. A coronal imaging slab was centered on the carotid bifurcation of the higher stenosis degree side. The coronal acquisition plane was chosen to minimize the inflow artifact from the blood, and achieve better longitudinal coverage. No spatial saturation was applied. Total acquisition time was 6 min 23 s, to obtain a mask image and 30 view-shared phases with a temporal resolution of 10.6 s. Coincident with the third phase, a bolus of 0.1 mmol/kg Gd- DTPA (Gadovist, Bayer Schering, Berlin, Germany) was administered using a power injector at the rate of 3 mL/s followed by a 20 mL saline flush. The CE-MRA data was obtained by subtracting the mask image from the multi-phase acquisition. In addition, for plaque component determination, the following sequences were also performed in the coronal plane: pre- and post-contrast 3D T1-weighted (T1w) delays alternating with nutation for tailored excitation (DANTE)-prepared fast spin echo [24], 3D time of flight (TOF) and 3D direct thrombus imaging (MR-DTI, inversion time of 300 ms) [25]. Detailed imaging parameters are listed in Table 1. Total scanning time was approximately 30 min.

Image analysis

The T1w and DCE images were reformatted into the axial plane with a 0.7 mm slice thickness using a dedicated workstation (AW4.6, GE Healthcare, Buc, France). For each patient, the carotid arteries on both sides were analyzed. Carotid vessel wall and lumen boundaries at each slice were manually drawn according to the T1w images, using a DICOM viewer (OsiriX 5.5.2, Pixmeo, Geneva, Switzerland). Plaque was defined as a focal wall thickness ≥1.5 mm [26]. The subtracted CE-MRA image at the fifth phase, which had the highest image contrast in the carotid artery, was used for morphological analysis. Plaque surface morphology was classified as either ulcerated/irregular or smooth using the maximum intensity projection (MIP) of CE-MRA images, based on previous published standards [10], by two experienced reviewers, both having more than 2 years of experience in carotid imaging. The two reviewers were blinded to the patients clinical information and made their judgement independently. The classification result from the first reviewer was used for further analysis. Luminal stenosis was measured for each plaque on both CE-MRA source image and 3D pre-contrast T1w images separately according to the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) criteria [23, 27]. The stenosis measured from CE-MRA source image was used for further analysis. This method has a reported high intra- and inter-observer reproducibility [8]. IPH was defined as bright pixels on the DTI image.

Pharmacokinetic modeling

Images from the 4D data were processed using the University of Washington (Seattle) vasa vasorum imaging (VVI) tool [28]. This approach firstly applies a Kalman Filtering Registration and Smoothing (KFRS) algorithm, to reduce the noise level in the image and correct patient motion [29]. A two-compartment Patlak model is then used to generate a parametric map known as the “vasa vasorum image (VVI)” showing partial plasma volume (v p) in shades of red and transfer constant (K trans) in shades of green. The relationship between blood and tissue signal concentration is modeled as follows:

where \(C_{\text{t}}\) and \(C_{\text{p}}\) represent the contrast agent concentration in the tissue and blood plasma, respectively. Lumen and wall boundaries manually segmented from T1w images were copied to the VVI. Manual adjustments were performed, as necessary to co-register the ROIs to the VVIs, by the reviewers who were blinded to the final results. Further details of the analysis can be found in Kerwin et al. [28]. Adventitial PK measurements were calculated by averaging all the pixels along the wall boundary. Plaque PK measurements were calculated by averaging all the pixels between the wall and lumen boundary. The overall PK parameters of each plaque were calculated as the mean value across all the plaque containing slices. To test the interrater reproducibility of this method, two reviewers preformed the analysis independently for all of the patients.

The PK parameter differences were evaluated using linear and non-linear assumptions of the signal intensity and Gd concentration. The following equations were used to calculate the Gd concentration:

where Eq. (2) calculates the pixel T 1 value according to its signal intensity based on the spoiled gradient echo sequence [30]. \(\alpha\) is the flip angle and M 0 is a constant value. Equation (3) calculates the Gd concentration (mmol/L) according to the pixel T 1 changes. T 1 and T 1,0 (s) are the current and native pixel T 1 values (blood T 1,0 = 1500 ms and vessel wall T 1,0 = 1000 ms from the literature value [31] were used). The corrected Gd concentration was then applied again to the 28 arteries using Eq. (1). The calculated PK parameters were then compared with the results from the linear assumption.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using R (version 3.2.2). The Shapiro–Wilk’s test was used to test normality assumptions. The Kappa statistic was performed to evaluate interrater agreement in ulceration detection. The Student’s t test was used to compare the PK parameters for smooth versus ulcerated/irregular plaques defined by the first reviewer, and also to compare hemorrhage and non-hemorrhage plaques. Pearson’s correlation was used to assess the relationship between PK parameters and luminal stenosis. The concordance correlation coefficient (CCC) was reported to assess the relationship between the stenosis measured by CE-MRA and 3D T1w images. The CCC and Bland–Altman plots were used to compare the differences between linear and non-linear assumptions of image signal and Gd concentration. The inter-rater agreement in PK parameters was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). A Chi-squared tests was used to compare proportions of patients with IPH. Parametric distributions were presented as mean ± SD. p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the 21 patients, three patients did not finish the examination due to discomfort, four carotid arteries were excluded from data analysis due to motion artefacts and four arteries were excluded due to occlusion. The rest of the images were of diagnostic quality, and used for further analysis. Atherosclerotic plaques were identified in the remaining 28 arteries, with a mean luminal stenosis of 44% (range 11–82%). Fourteen plaques were classified as ulcerated/irregular and fourteen were classified as smooth. In the 28 arteries analyzed, two independent reviewers agreed in 26 (93%) cases for plaque surface morphology classification (\(\kappa = 0.79\); 95% CI 0.56–1.00). The PK parameters (K trans and v p in adventitia and plaque) were normally distributed (p > 0.05). For the luminal stenosis, the correlation between CE-MRA and 3D T1w was good (r = 0.89).

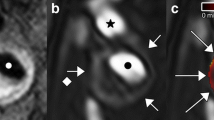

The images in Fig. 1 are from a symptomatic patient, with a 52% stenosis on the right side. The plaque contains a large intraplaque hemorrhage (IPH). Figure 1c shows the intra-luminal and adventitial signal change with time following contrast agent administration. Figure 2 is from the same artery and shows the multi-contrast MR images and calculated VVI. An ulceration can be clearly seen on the CE-MRA images, but is not so apparent on the 3D TOF-MRA. Surface irregularity can be observed in both pre- and post-contrast T1w images. The MR-DTI shows a large region of IPH. The VVI shows regions of high K trans around the ulceration and at the adventitia boundary, with a relatively low K trans inside the IPH, which is in agreement with a previous study [32].

a Shows DCE images at different time frames at a single slice location within an ICA branch of the plaque. The dashed red and green lines in frame 5 show the boundary of carotid lumen and adventitia. b Shows the corresponding black blood T1w image with red and green lines delineating the lumen and wall boundary. c Represents the mean signal intensity time course within the lumen (red) and adventitia (green)

An ulcerated plaque in the multi-contrast MR protocol, including MIP from CE-MRA, oblique and axial reformat of CE-MRA, TOF-MRA, T1w, DTI, CE-T1w and VVI. The white arrow in CE-MRA suggests the ulcer arises perpendicularly from the lumen. The ulcer can be clearly seen on the CE-MRA images, while it is not clearly visible on the TOF-MRA images. The pre-contrast T1w image shows the lumen surface irregularity, and a thin or ruptured FC can be seen on the post-contrast T1w images (black arrow). The hyperintense area on MR-DTI represents a large intraplaque haemorrhage/thrombus (white arrow). The VVI has the range of v p from 0 to 65% and K trans from 0 to 0.5 min−1 which shows a high K trans region at the adventitia

The PK values from the linear assumption were used for the statistical analysis. Adventitial and plaque K trans in ulcerated/irregular plaques were significantly higher compared to smooth plaques (Fig. 3a, b, adventitial K trans 0.079 ± 0.018 vs. 0.064 ± 0.011 min−1, p = 0.02; plaque K trans 0.065 ± 0.013 vs. 0.055 ± 0.010 min−1, p = 0.03, respectively). Whilst v p demonstrated no significant difference between groups (Fig. 3c, d, adventitial v p 9.3 ± 5.3% vs. 9.8 ± 4.8%, p = 0.81; plaque v p 13.5 ± 5.5% vs. 11.8 ± 4.9%, p = 0.32, respectively).

Positive correlations between adventitial K trans and v p with the degree of stenosis were observed (Fig. 4a, b, r = 0.44, p = 0.02 for adventitial K trans; r = 0.55, p = 0.01 for adventitial v p, respectively). While no significant correlation was observed for plaque K trans or v p with stenosis (Fig. 4c, d, r = 0.23, p = 0.24 for plaque K trans; r = 0.12, p = 0.55 for plaque v p, respectively).

The CCC comparing the linear and non-linear assumptions for adventitial K trans, plaque K trans, adventitial v p and plaque v p were: 0.95, 0.93, 0.99 and 0.99, respectively. There was highly significant concordance between the linear or non-linear assumptions (all p < 0.001), though there is a significant bias in PK values when using the linear and non-linear assumption of image signal to Gd concentration. Figure 5 demonstrated the Bland–Altman plots comparing both assumptions.

Bland-Altman plots of the PK parameters derived after modelling the linear and non-linear relationships of signal intensity and Gd concentration. There is a significantly bias in PK values when using linear and non-linear assumption of image signal to Gd concentration. Note that \(K_{1}^{\text{trans}}\) and v p1 represent the linear model, and \(K_{2}^{\text{trans}}\) and v p2 represent the non-linear model

IPH was found in eight plaques. Within this group, six arteries had ulcerated plaques and two had smooth plaques. In the 20 plaques without IPH, we noted that smooth plaques were more common (12 had smooth plaques), however, these respective proportions were not significantly different (p = 0.28). Plaques with hemorrhage have higher mean adventitial K trans values compared with plaques with no hemorrhage (0.078 ± 0.019 vs. 0.069 ± 0.015 min−1), however the difference here was not significant (p = 0.2).

The agreement for the four measured DCE parameters between the two reviewers was good. The ICC for adventitial K trans, plaque K trans, adventitial v p and plaque v p are 0.88, 0.93, 0.81 and 0.71, respectively.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first application of a 4D sequence to acquire both high spatial and temporal resolution DCE-MRI and CE-MRA of the carotid artery, allowing for combined morphological and functional assessment of carotid atherosclerosis from a single contrast administration. The results show that adventitial and plaque K trans were higher in ulcerated/irregular plaques compared to smooth plaques. Adventitial K trans and v p were also positively correlated with the degree of luminal stenosis.

Carotid plaque ulceration, characterized as an intimal defect with the intraplaque component exposed to the lumen [9], can form emboli and thrombosis leading to ischemic neurologic symptoms. Sitzer et al. showed plaque ulceration and lumen thrombus are the main sources of cerebral microemboli [9]. Multiple studies have also shown that plaque ulceration is associated with cerebral infarcts, TIA and amaurosis fugax [8, 11]. In this study, plaque enhancement could be observed in both smooth and ulcerated plaques and the derived VVI showed significant differences in PK parameters between both of these plaque types. The results demonstrate that ulcerated plaques are more prevalent to neovascularization and possibly inflammation. Plaque ulceration or fibrous cap discontinuity may induce more inflammatory cell infiltration into the plaque, which in turn further weakens the fibrous cap and eventually causes the plaque to rupture. This suggests quantitative analysis of DCE-MRI could provide more information than conventional contrast-enhanced morphological images in identifying lesions at higher risk.

While only adventitial K trans and v p are correlated with luminal stenosis, no significant correlation was observed between whole plaque PK values and the stenosis. This might be due to a lower sensitivity as a result of averaging PK parameters across the whole plaque region. While various plaque components such as IPH, lipid core and fibrous tissue have different PK values [32], simple averaging of PK parameters across the plaque region may be insufficient for quantitative analysis and risk stratification. A positive correlation between luminal stenosis and adventitial K trans and v p was observed in this study (Fig. 4a, b), indicating a relationship between plaque growth and adventitial neovascularization. These microvessels within the atherosclerotic lesion have shown close association with inflammatory cells [33] which indicate that these could serve as a pathway for the macrophage entry into the plaque that leads to chronic inflammation hence promoting plaque development.

The presence of intraplaque hemorrhage (IPH) has also been found to be associated with increased adventitial K trans [34]. In our study, plaques with IPH had higher adventitial K trans, however the difference was not significance. The reason for this may due to lack of statistical power, as only a small number of plaques (eight) contained IPH. Although the exact etiology of the IPH is still unclear it is suggested that most likely the rupture of fragile and leaky neovessels that vascularize the developed plaque leads to IPH [35].The histopathological evidence also supports the relationship of IPH to the presence of neovessels [36]. In our study, IPH was absent in most of the plaques. The correlation between PK parameters and surface morphology also applies to the plaques without IPH, indicating ulceration and a high degree of stenosis were two other factors, apart from IPH, which could present with increased plaque neovascularization and inflammation.

The use of multi-contrast MRI allows for detailed analysis of plaque composition and vulnerability assessment, which could provide more insight than simple luminal stenosis measurements [37]. This study demonstrates that a combined 4D DCE-MRI/MRA acquisition in combination with multi-contrast 3D sequences can aid in the identification of high-risk plaque features. Our study also demonstrates that these features can be obtained in a clinically acceptable scan time of approximately 30 min.

There are several limitations in this study. Firstly, no histological validation was performed on the plaques. However the correlation between DCE-MRI and neovascularization as well as inflammation has been demonstrated in previous studies [19, 21, 28], and CE-MRA is considered reliable for observing plaque surface morphology [13, 16]. The second limitation is that only a small patient cohort was included in this study. As discussed above, the K trans difference between IPH groups was not significant, this might be due to the resultant lack of statistical power. Thirdly, the view-ordering used in this study could smooth the temporal information, especially during the injection period. However, this is not considered to be a significant effect and other studies have used similar analysis for various DCE applications, including breast [38, 39], prostate [40] and also animal models [41]. The last limitation is that a thick coronal imaging slice (1.4 mm) was used in this study. This might bring errors in calculating the PK values for the thin vessel wall. Future protocol design could consider increasing axial resolution for a more precise analysis.

Conclusion

This study investigated the relationship between PK modeling with carotid plaque surface morphology by simultaneously acquiring 4D DCE-MRI and CE-MRA. Adventitial and plaque K trans from DCE-MRI analysis is significantly higher in ulcerated plaques than smooth ones. Also, adventitial K trans and v p are correlated with luminal stenosis.

References

Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS (2012) Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update a report from the American heart association. Circulation 125(1):2–220

Goldstein LB, Bushnell CD, Adams RJ, Appel LJ, Braun LT, Chaturvedi S, Creager MA, Culebras A, Eckel RH, Hart RG (2011) Guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 42(2):517–584

DeBakey ME (1996) Carotid endarterectomy revisited. J Endovasc Surg 3(1):4

Moore WS, Barnett H, Beebe HG, Bernstein EF, Brener BJ, Brott T, Caplan LR, Day A, Goldstone J, Hobson RW (1995) Guidelines for carotid endarterectomy a multidisciplinary consensus statement from the Ad Hoc Committee, American Heart Association. Stroke 26(1):188–201

Njemanze P, Beck O, Gomez C, Horenstein S, Cujec B, Polasek P, Voll C, Shuaib A, Lee R, Bartzokis T (1991) North American symptomatic carotid endarterectomy trial. Methods, patient characteristics, and progress. Stroke 22(6):711–720

Rothwell P, Eliasziw M, Gutnikov S, Fox A, Taylor D, Mayberg M, Warlow C, Barnett H, Collaboration CET (2003) Analysis of pooled data from the randomised controlled trials of endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis. Lancet 361(9352):107–116

Ballotta E, Da Giau G, Renon L (2000) Carotid plaque gross morphology and clinical presentation: a prospective study of 457 carotid artery specimens. J Surg Res 89(1):78–84

Rothwell PM, Gibson R, Warlow C (2000) Interrelation between plaque surface morphology and degree of stenosis on carotid angiograms and the risk of ischemic stroke in patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis. Stroke 31(3):615–621

Sitzer M, Müller W, Siebler M, Hort W, Kniemeyer H-W, Jäncke L, Steinmetz H (1995) Plaque ulceration and lumen thrombus are the main sources of cerebral microemboli in high-grade internal carotid artery stenosis. Stroke 26(7):1231–1233

Lovett J, Gallagher P, Hands L, Walton J, Rothwell P (2004) Histological correlates of carotid plaque surface morphology on lumen contrast imaging. Circulation 110(15):2190–2197

Eliasziw M, Streifler JY, Fox AJ, Hachinski VC, Ferguson GG, Barnett H (1994) Significance of plaque ulceration in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. North American symptomatic carotid endarterectomy trial. Stroke 25(2):304–308

Carr S, Farb A, Pearce WH, Virmani R, Yao JS (1996) Atherosclerotic plaque rupture in symptomatic carotid artery stenosis. J Vasc Surg 23(5):755–766

Randoux B, Ba Marro, Koskas F, Duyme M, Sahel M, Zouaoui A, Marsault C (2001) Carotid artery stenosis: prospective comparison of CT, three-dimensional gadolinium-enhanced MR, and conventional angiography 1. Radiology 220(1):179–185

Nederkoorn PJ, Willem PTM, Eikelboom BC, Elgersma OE, Buskens E, Hunink MM, Kappelle LJ, Buijs PC, Wüst AF, van der Lugt A (2002) Preoperative diagnosis of carotid artery stenosis accuracy of noninvasive testing. Stroke 33(8):2003–2008

U-King-Im J, Trivedi R, Cross J, Higgins N, Graves M, Kirkpatrick P, Antoun N, Gillard J (2004) Conventional digital subtraction X-ray angiography versus magnetic resonance angiography in the evaluation of carotid disease: patient satisfaction and preferences. Clin Radiol 59(4):358–363

Etesami M, Hoi Y, Steinman D, Gujar S, Nidecker A, Astor B, Portanova A, Qiao Y, Abdalla W, Wasserman B (2013) Comparison of carotid plaque ulcer detection using contrast-enhanced and time-of-flight MRA techniques. Am J Neuroradiol 34(1):177–184

Yuan J, Usman A, Das T, Patterson A, Gillard J, Graves M (2016) Imaging carotid atherosclerosis plaque ulceration: comparison of advanced imaging modalities and recent developments. Am J Neuroradiol. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A5026

Korosec FR, Frayne R, Grist TM, Mistretta CA (1996) Time-resolved contrast-enhanced 3D MR angiography. Magn Reson Med 36(3):345–351

Kerwin W, Hooker A, Spilker M, Vicini P, Ferguson M, Hatsukami T, Yuan C (2003) Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging analysis of neovasculature volume in carotid atherosclerotic plaque. Circulation 107(6):851–856

Gaens ME, Backes WH, Rozel S, Lipperts M, Sanders SN, Jaspers K, Cleutjens JP, Sluimer JC, Heeneman S, Daemen MJ (2013) Dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging of carotid atherosclerotic plaque: model selection, reproducibility, and validation. Radiology 266(1):271–279

Kerwin WS, O’Brien KD, Ferguson MS, Polissar N, Hatsukami TS, Yuan C (2006) Inflammation in carotid atherosclerotic plaque: a dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging study 1. Radiology 241(2):459–468

Qiao Y, Etesami M, Astor B, Zeiler S, Trout H, Wasserman B (2012) Carotid plaque neovascularization and hemorrhage detected by MR imaging are associated with recent cerebrovascular ischemic events. Am J Neuroradiol 33(4):755–760

Barnett H, Taylor D, Eliasziw M, Fox A, Ferguson G, Haynes R, Rankin R, Clagett G, Hachinski V, Sackett D (1998) North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. Benefit of carotid endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic moderate or severe stenosis. N Engl J Med 339(20):1415–1425

Zhu C (2014) High resolution black blood magnetic resonance imaging of atherosclerotic plaque. PhD Thesis, University of Cambridge

Priest AN, Joubert I, Hilborne S, Hunter S, Bowden DJ, Graves MJ, Baglin T, Gillard JH, John D (2013) MR Direct Thrombus Imaging with optimised signal and improved lipid suppression. In: Proceedings of the 21st scientific meeting, International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, Salt Lake City, p 1280

Kitamura A, Iso H, Imano H, Ohira T, Okada T, Sato S, Kiyama M, Tanigawa T, Yamagishi K, Shimamoto T (2004) Carotid intima-media thickness and plaque characteristics as a risk factor for stroke in Japanese elderly men. Stroke 35(12):2788–2794

Naylor A, Rothwell P, Bell P (2003) Overview of the principal results and secondary analyses from the European and North American randomised trials of endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 26(2):115–129

Kerwin W, Oikawa M, Yuan C, Jarvik G, Hatsukami T (2008) MR imaging of adventitial vasa vasorum in carotid atherosclerosis. Magn Reson Med 59(3):507–514

Kerwin W, Cai J, Yuan C (2002) Noise and motion correction in dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI for analysis of atherosclerotic lesions. Magn Reson Med 47(6):1211–1217

Graves MJ (2007) Pulse sequences for contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Radiography 13:e20–e30

Li L, Chai JT, Biasiolli L, Robson MD, Choudhury RP, Handa AI, Near J, Jezzard P (2014) Black-blood multicontrast imaging of carotid arteries with DANTE-prepared 2D and 3D MR imaging. Radiology 273(2):560–569

Chen H, Cai J, Zhao X, Underhill H, Ota H, Oikawa M, Dong L, Yuan C, Kerwin WS (2010) Localized measurement of atherosclerotic plaque inflammatory burden with dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. Magn Reson Med 64(2):567–573

Truijman MT, Kwee RM, van Hoof RH, Hermeling E, van Oostenbrugge RJ, Mess WH, Backes WH, Daemen MJ, Bucerius J, Wildberger JE (2013) Combined 18F-FDG PET-CT and DCE-MRI to assess inflammation and microvascularization in atherosclerotic plaques. Stroke 44(12):3568–3570

Sun J, Song Y, Chen H, Kerwin WS, Hippe DS, Dong L, Chen M, Zhou C, Hatsukami TS, Yuan C (2013) Adventitial perfusion and intraplaque hemorrhage: a dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI study in the carotid artery. Stroke 44(4):1031–1036

Kolodgie FD, Gold HK, Burke AP, Fowler DR, Kruth HS, Weber DK, Farb A, Guerrero L, Hayase M, Kutys R (2003) Intraplaque hemorrhage and progression of coronary atheroma. N Engl J Med 349(24):2316–2325

Moreno PR, Purushothaman K-R, Sirol M, Levy AP, Fuster V (2006) Neovascularization in human atherosclerosis. Circulation 113(18):2245–2252

Wasserman BA (2010) Advanced contrast-enhanced MRI for looking beyond the lumen to predict stroke building a risk profile for carotid plaque. Stroke 41(10 Suppl 1):S12–S16

Tudorica LA, Oh KY, Roy N, Kettler MD, Chen Y, Hemmingson SL, Afzal A, Grinstead JW, Laub G, Li X (2012) A feasible high spatiotemporal resolution breast DCE-MRI protocol for clinical settings. Magn Reson Imaging 30(9):1257–1267

Bedair R, Graves MJ, Patterson AJ, McLean MA, Manavaki R, Wallace T, Reid S, Mendichovszky I, Griffiths J, Gilbert FJ (2015) Effect of radiofrequency transmit field correction on quantitative dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging of the breast at 3.0 T. Radiology 279(2):368–377

Rödel S, Blaut S, Dürig E, Haroske G, Steinbach F, Kittner T, Dresden D (2014) Prostate: multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) and MR-guided biopsy (MR-GB). ECR 2014/C-2079. doi:10.1594/ecr2014/C-2079

Haeck J, Bol K, Bison S, Tiel S, Koelewijn S, Jong M, Veenland J, Bernsen M (2015) Optimized time-resolved imaging of contrast kinetics (TRICKS) in dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI after peptide receptor radionuclide therapy in small animal tumor models. Contrast Media Mol Imaging 10(6):413–420

Acknowledgements

The Vasa Vasorum Image tool was kindly provided by Dr. William Kerwin of the Vascular Imaging Laboratory of the University of Washington. We thank Dr. Andrew Gill for insightful discussions.

Funding

The project was supported by the Addenbrooke’s Charitable Trust and the NIHR comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre award to Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust in partnership with the University of Cambridge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JY participated in the study design, contributed to data acquisition, analysis, interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. GCM was involved in study design, funding application, recruiting the patients and revising the manuscript. AJP and MJG designed the study, supervised the data acquisition, analysis, interpretation and prepared the manuscript. AU was involved in patient recruitment, data analysis and revising the manuscript. TD was involved in data analysis and revising the manuscript. ANP developed and tested the direct thrombus imaging sequence, and revised the manuscript. PD was involved in patient scanning and revising the manuscript. SH was involved in patient recruitment, scanning and revising the manuscript. ZT was involved in discussion and revising the manuscript. JHG supervised the study, and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Yuan, J., Makris, G., Patterson, A. et al. Relationship between carotid plaque surface morphology and perfusion: a 3D DCE-MRI study. Magn Reson Mater Phy 31, 191–199 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10334-017-0621-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10334-017-0621-4