Abstract

Background

MR plaque imaging is a valuable tool in characterizing carotid atherosclerotic plaque and identifying high-risk features. There are limited data on the role of the widely available single-shot diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) in plaque characterization along with histological correlation. This study aimed to correlate the plaque characteristics identified by MR imaging in vivo at the level of maximum stenosis with histological plaque characteristics in the postoperative specimen.

Methods

Patients who underwent carotid endarterectomy in a tertiary care center during one and half years were prospectively recruited for non-contrast MR carotid plaque imaging (including single-shot EPI-DWI sequence) in a 3 Tesla MRI using a dedicated carotid coil. An experienced radiologist correlated DWI sequence findings with histopathology of postsurgical sections to confirm the high-risk features.

Results

Twenty-three patients (mean age 66.1 years ± SD 6.25) were evaluated, of which 65% were males and 96% were symptomatic. Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values in location of plaques could differentiate histopathological unstable from stable plaques (0.83 × 10–3 mm2/s vs 1.7 × 10–3 mm2/s; p 0.001), with a sensitivity and specificity of 75% and 79%, respectively, at an ADC cutoff of 1.24 × 10–3 mm2/s. Plaques with and without lipid-rich necrotic core (0.86 × 10–3 mm2/s vs 1.44 × 10–3 mm2/s; p = 0.042) as well as intraplaque hemorrhage could be differentiated (0.751 × 10–3 mm2/s vs 1.352 × 10–3 mm2/s; p 0.037) using the apparent diffusion coefficients.

Conclusion

The widely available single-shot EPI-DWI in assessing plaque characteristics in carotid stenosis is promising and correlated with histopathological features. Diffusion-weighted imaging will be a helpful adjunct in patients when contrast administration is intolerable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

MR imaging of the carotid plaque has evolved as an essential tool for detecting high-risk plaque characteristics, mainly since 25–50% of ischemic strokes are caused by an unstable carotid artery plaque [1]. There is a growing awareness that stenosis severity alone has limited value in predicting plaque stability. Various molecular processes have shown to be associated with plaque vulnerability, independent of the degree of stenosis. Symptomatic patients were more likely to have a thin fibrous cap (30–50%), intra-plaque hemorrhage (45–60%), a large lipid core (50–80%), and a complex morphology (61.5%) in MR imaging [2, 3]. Additionally, these characteristics are independent predictors of future ischemic events. Though contrast-enhanced MRI sequence is needed for characterizing plaque, recently published American Society of Neuroradiology consensus statement recommends non-contrast protocols as well [4]. Standard single-shot EPI-DWI with ADC measurement has been evaluated only sparingly for plaque assessment in the published literature with most studies having in vitro evaluation and small samples. This study aims to evaluate the utility of comparing single-shot EPI-DWI at the level of maximum stenosis for plaque vulnerability assessment compared to the histopathological specimen and identify the high-risk features that are likely to translate into variations in ADC values. Single-shot EPI-DWI was chosen as part of the study since it is the most widely available diffusion sequence across vendors, thus enabling its universal application compared to the newer DWI sequences. Since DWI does not require contrast administration, it can be an adjunct tool in patients who require avoidance of contrast agents as in chronic kidney disease, allergies, and serial follow-up on medical management.

Methods

This was a prospective study conducted from October 2018 to June 2020 in a single center after obtaining the institutional ethics committee approval. Informed written consent was obtained from all the participants. Twenty-seven consecutive patients who sought medical care after at least one major or minor cerebrovascular event and having a moderate to severe carotid artery stenosis (> 50% stenosis) were planned for carotid endarterectomy after a multidisciplinary stroke team meeting according to the European Society for Vascular Surgery guidelines of 2017 [5]. Patients not consenting for the MR examination and patients with a pacemaker or metallic implant in the body were excluded from the study. The study patients underwent carotid plaque MR imaging in a 3.0 Tesla machine (General Electric Discovery 750E, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) using a 6-channel carotid coil. Before placing the patient in the MR scanner, the level of the maximum carotid stenosis was marked over the skin using ultrasonography to ensure optimal carotid surface coil position and resultant better signal. The sequences used included T1, T2, T2FS, TOF, PD, and DWI (total acquisition time ~ 23.5 min). The protocols for the primary sequences were as described in previous papers [6,7,8].The standard diffusion-weighted echo-planar sequence was used as part of the study to provide a degree of robustness against the involuntary patient motion and keep acquisition times clinically acceptable. In DWI acquisition, saturation bands were positioned superiorly and inferiorly to suppress signals from in-flowing blood and anteriorly and posteriorly to minimize wraparound artifact. The b values used in the study were 10, 500, and 1000. A baseline b value of 10 was taken instead of 0 for nulling the blood flow signals resulting from neovascularization of the plaque which might confound the effect of necrosis or hemorrhage [9]. Other DWI parameters were TE 71.5 ms; TR 3800 ms; matrix size 120 × 60; section thickness 2 mm; and acquisition time 4.2 min. Zero interpolation algorithm (ZIP) was applied in T2, T2 FS, and PD sequences. Images were assessed on the GE Advantage workstation (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) version 4.6 using the GenIQ application. The site of maximum carotid plaque thickness was identified on 3D TOF MRA in the workstation. A corresponding cross section of the carotid artery image in the DWI sequence was used to measure the ADC values of the plaque. For ADC map generation, ROI was drawn after correlation with T2 and T2 FS sequences in corresponding slices to confirm the plaque's outer and inner limits (Figs. 1, 2, 3). These images were analyzed by a reader with more than 5 years of experience in interpreting diagnostic vascular imaging studies. The DWI and ADC images were analyzed for the image-quality-cum diagnostic confidence and graded using a 4-point scale. An image-quality rating from 1 to 4, with 1 being poor and 4 being excellent, was assigned before the review. Studies with an overall image quality rating of 1 and 2 were excluded. Further, the patient underwent surgery on an average of 4 days after magnetic resonance imaging.

Carotid MR images of an ICA plaque in a 70-year-old diabetic male who had symptomatic left MCA stroke, who had NIHS score of 8 at admission, and no prior cerebrovascular events were detected to have 72% stenosis in MR TOF (a, b), with the ICA plaque (arrows) showing TOF(A) and T1 (c) hyperintensity indicative of intraplaque hemorrhage. The plaque appeared predominantly hyperintense in T2 (d), PD (e), and T2FS (f). DWI image (g) showing plaque with inset showing ADC map with margins of vessel wall and vessel lumen demarcated by line tracing adapted from corresponding T2FS image. The plaque had average ADC value of 0.83 × 10–3 mm2/s. Histopathological images (h, i) of the same plaque showing intraplaque hemorrhage (*) containing RBCs admixed with few cholesterol clefts. (Hematoxylin and eosin, h original magnification 50×, scale bar 200 μm, i original magnification 200×, scale bar 50 μm)

Carotid MR images of a 66-year hypertensive female with left ICA stenosis detected following right upper limb paresis. TOF images (a, b) showed mildly hyperintense plaque (arrows) involving carotid bulbs extending into the proximal left ICA causing ~ 80% stenosis. T1 image (c) showed the plaque to have iso-hyperintense areas, which showed hyperintensity in PD (d) compared to T2 (e), suggesting lipid-rich plaque. The plaque, as identified better in a T2 FS (f) image, showed hyperintense areas in and DWI (g) with an ADC value (inset, g) of 0.41 x 10-3mm2/sec. Post endarterectomy, histopathological analysis (h, i) showed necrotic lipid core with inflammatory cell infiltrate (arrows in h - Haematoxylin and Eosin, original magnification 50X, Scale bar 200 μm, i - Original magnification 100X, Scale bar 100 μm).

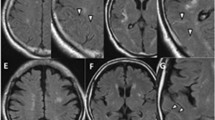

Carotid MR images of a 65-year-old male with left hemiparesis, who was detected to have right ICA 80% stenosis (arrows). His NIHS at admission was 6, with a total of 2 cerebrovascular events before surgery. TOF images (a, b) showing right ICA stenosis with axial TOF showing a largely preserved periluminal dark band indicative of intact fibrous cap. T1 image (c) showed mildly increased signal with T2 (d) and PD (e), showing the plaque to have largely similar intensities. T2 FS (f) also showed the luminal stenosis with DWI image (g) with an ADC value of 1.290 × 10–3 mm2/s (inset in g)

A total of 27 study patients were recruited of which 92.6% of the cases had adequate image quality to interpret plaque characteristics. Two participants were excluded due to the suboptimal image quality in MRI, and two more were excluded due to inadequacy of specimen for histopathological assessment.

Histology protocol

The endarterectomy specimens were fixed in buffered formalin immediately after surgery. Serial cross sections were taken from the specimens at 2-mm intervals and processed as per standard protocols in the histopathology laboratory. For all cases, the entire endarterectomy specimen was processed. However, the maximum carotid luminal narrowing level was used to align with corresponding MR sections for correlation. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Masson’s trichrome (MAT), and elastic van Gieson (EVG) stains were performed on 5-μm sections. The pathologist assessed all the slides, and the histological features were scored using a semiquantitative method as described by Lovett et al. [10, 11]. For analysis, probably and definitely unstable plaques with grade 3/4 lipid necrotic core and intraplaque hemorrhage were categorized as being vulnerable and the rest were categorized as being stable. For analysis, only large lipid necrotic core and intraplaque hemorrhage were considered instability features. A similar criterion was also followed in imaging studies.

Statistical analysis

Each patient contributed only 1 set of observations (i.e., from only one carotid artery) to the dataset for analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Version 23.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY) software. Descriptive statistical tools were used for basic frequencies of plaque characteristics and patient demographics. An independent sample t test was used for the comparison of mean ADC values between each of the plaque characteristics and overall plaque vulnerability. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to assess optimal ADC value in detecting plaque vulnerability.

Results

Demographics and risk factors in the study population

The demographic and clinical data of the final 23 patients of the study are summarized in Table 1. 17.3% of the study patients had moderate (50–70%) carotid stenosis. 69.5% of the plaques revealed unstable features on histopathological evaluation.

DWI and ADC value relation with plaque composition

The mean ADC values could differentiate vulnerable from non-vulnerable plaques (0.83 × 10–3 mm2/s vs. 1.7 × 10–3 mm2/s; p 0.001).

Besides, it also revealed a significant difference in mean ADC values in plaques with lipid necrotic core (0.86 × 10–3 mm2/s) and absent lipid necrotic core (1.44 × 10–3 mm2/s).

The mean ADC values between plaques with hemorrhage (0.751 × 10–3 mm2/s) and without hemorrhage (0.751 × 10–3 mm2/s) was also statistically significant (p = 0.037). The findings are summarized in Table 2.

ROC analysis (Fig. 4) with an ADC value of 1.1145 × 10–3 mm2/s had a sensitivity of 71.4% and specificity of 81.2%. Representative cases of vulnerable and non-vulnerable plaques are shown in Figs. 1, 2 and 3, respectively.

Discussion

Identifying the plaques as vulnerable will allow a more vigilant follow-up strategy and early interventions to these plaques despite presenting as mild stenosis or as incidental findings. ADC was found to be better than even T1/T2 mapping techniques in differentiating fibrous plaques and lipid-rich necrotic plaques by Clarke et al. [12]. Our study used the plaque characteristics at the maximum stenosis in MRI and histopathology for comparison; on the contrary, most of the previous studies that assessed DWI have used average ADC value from multiple levels of plaque for evaluation of plaque composition [9, 13, 14]. This was based on the notion that the most aggressive part of the plaque would be at level of maximum stenosis and the ADC characteristics of that level will predict the vulnerability in the most representative manner. Our study showed that the EPI-DWI sequence with ADC measurement is effective in differentiating histologically stable and unstable plaques. A significant difference in mean ADC values between vulnerable and non-vulnerable plaques was depicted with a cutoff of 1.24 × 10–3 mm2/s, with a sensitivity of 75% and specificity of 79%. This was despite the overall moderate image quality compared to a few of the recent studies which used 3D DWI, at the cost of increased acquisition time. DWI was found to be applicable for the assessment of carotid plaque by Kim et al. [15] using 2D ss-IMIV-DWEPI sequence with both in vivo and ex vivo mean ADC measurement on 8 study patients and documented detection of the lipid necrotic core. In their study, the mean ADC for normal vessel wall and hemorrhage was 1.27 × 10–3 and 0.98 × 10–3 mm2/s, respectively. 2D ss-IMIV-DWEPI was used to avoid the geometrical distortion in EPI. 3D DWI was used for a better depiction of the vessel wall by Xie et al. [13], but no histological correlation was done as part of the study.

In our study, plaques with and without lipid-rich necrotic core could also be differentiated. Earlier ex vivo studies had already evaluated the utility of decreased ADC in necrotic core detection, with only very limited in vivo studies with a relatively small sample size [9, 16]. In the study by Kim et al., the lipid-rich necrotic core had a mean ADC of 0.38 × 10–3 mm2/s as against our values of 0.86 × 10–3 mm2/s, which was similar to values in the study by Ota et al. [9] Our ADC values also were similar to the results by Young et al., with the ADC value for lipid core being 0.73 × 10–3 mm2/s using EPI-DWI sequence [14].

The initial study done by Yao et al. on intraplaque hemorrhage detection using ADC values in 3T MRI showed that the mean ADC value in IPH was 0.985 ± 0.376 μm2 [17]. However, the study did not have histopathological evaluation. In the study by Kim et al. and Ota et al., there was an overlap between ADC values of hemorrhage and lipid-rich necrotic core [9, 15]. Moreover, in the study by Ota et al., there was a considerable difference in ADC values between the two institutions where the study was done. We found a considerable overlap of ADC values within hemorrhage and lipid-rich necrotic cores possibly due to the various stages of the hemorrhage, coexistent lipid necrosis with hemorrhage, and inherent errors of the sequence used for assessment.

Compared to the previous studies which did histopathological correlations, our study had a reasonable sample size [7, 12]. The technical ease of doing endarterectomy was similar in both subsets of plaques. The vulnerable plaque carries a slightly higher theoretical risk for distal emboli while dissecting the vessel; however, no such differences were noticed in our patients. The use of readily available EPI-DWI makes the sequence suitable for routine use, unlike the majority of the studies which have used various modifications of the sequence.

Limitations

The limited number of patients in our study would have reduced our sensitivity in differentiation of various pathologies. All our study patients had moderate to severe stenosis (≥ 50%); thus, visualization of the plaque in our protocols was not much of an issue. Hence, its applicability in patients with 50–70% stenosis may be potentially used for decision-making for revascularization. However, the utility in patients with < 50% stenosis with reduced plaque burden may be limited. Inter- and intraobserver variability was not assessed in this study, which would have evaluated the reproducibility of this modality. The unavailability of the newer motion correction sequences may also have influenced image acquisition. The inclusion of only > 50% stenosis patients who mostly had prior cerebrovascular events is in itself a selection bias, as is the case in all similar studies in the literature. Evaluation with much larger samples may be vital in validating the findings and their utility.

Conclusions

The standard DWI with ADC assessment at the level of maximum stenosis of the carotid artery in delineating plaque characteristics correlates with histopathology. Diffusion-weighted imaging will be a helpful adjunct in patients when contrast administration is intolerable.

Availability of data and materials

The data are available from institutes Picture Archiving and Communication System after taking Institutional Ethical Approval.

Abbreviations

- 3T:

-

3-Tesla

- ADC:

-

Apparent diffusion coefficient

- DWI:

-

Diffusion-weighted imaging

- EPI:

-

Echo planar imaging

- H & E:

-

Hematoxylin and eosin

- IPH:

-

Intra-parenchymal hemorrhage

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PD:

-

Proton density

- ss-IMIV-DWEPI:

-

Single-shot interleaved multislice inner volume diffusion-weighted echo planar imaging

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- ROI:

-

Region of interest

- TOF:

-

Time of flight

- TR:

-

Repetition time

References

Adams HP, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, Biller J, Love BB, Gordon DL, Marsh EE (1993) Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke 24:35–41. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.24.1.35

U-King-Im JM, Tang TY, Patterson A, Graves MJ, Howarth S, Li Z-Y, Trivedi R, Bowden D, Kirkpatrick PJ, Gaunt ME, Warburton EA, Antoun NM, Gillard JH (2008) Characterisation of carotid atheroma in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients using high resolution MRI. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 79:905–912. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2007.127969

Verhoeven B, Hellings WE, Moll FL, de Vries JP, de Kleijn DPV, de Bruin P, Busser E, Schoneveld AH, Pasterkamp G (2005) Carotid atherosclerotic plaques in patients with transient ischemic attacks and stroke have unstable characteristics compared with plaques in asymptomatic and amaurosis fugax patients. J Vasc Surg 42:1075–1081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2005.08.009

Saba L, Yuan C, Hatsukami TS, Balu N, Qiao Y, DeMarco JK, Saam T, Moody AR, Li D, Matouk CC, Johnson MH, Jäger HR, Mossa-Basha M, Kooi ME, Fan Z, Saloner D, Wintermark M, Mikulis DJ, Wasserman BA, Vessel Wall Imaging Study Group of the American Society of Neuroradiology (2018) Carotid artery wall imaging: perspective and guidelines from the ASNR vessel wall imaging study group and expert consensus recommendations of the American society of neuroradiology. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 39:E9–E31. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A5488

Aboyans V, Ricco J-B, Bartelink M-LEL, Björck M, Brodmann M, Cohnert T, Collet J-P, Czerny M, De Carlo M, Debus S, Espinola-Klein C, Kahan T, Kownator S, Mazzolai L, Naylor AR, Roffi M, Röther J, Sprynger M, Tendera M, Tepe G, Venermo M, Vlachopoulos C, Desormais I, ESC Scientific Document Group (2018) 2017 ESC Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases, in collaboration with the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS): Document covering atherosclerotic disease of extracranial carotid and vertebral, mesenteric, renal, upper and lower extremity arteriesEndorsed by: the European Stroke Organization (ESO)The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur Heart J 39:763–816. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx095

Hingwala D, Kesavadas C, Sylaja PN, Thomas B, Kapilamoorthy TR (2013) Multimodality imaging of carotid atherosclerotic plaque: going beyond stenosis. Indian J Radiol Imaging 23:26–34. https://doi.org/10.4103/0971-3026.113616

Cai J, Hatsukami TS, Ferguson MS, Kerwin WS, Saam T, Chu B, Takaya N, Polissar NL, Yuan C (2005) In vivo quantitative measurement of intact fibrous cap and lipid-rich necrotic core size in atherosclerotic carotid plaque: comparison of high-resolution, contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging and histology. Circulation 112:3437–3444. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.528174

Saam T, Ferguson MS, Yarnykh VL, Takaya N, Xu D, Polissar NL, Hatsukami TS, Yuan C (2005) Quantitative evaluation of carotid plaque composition by in vivo MRI. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25:234–239. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.ATV.0000149867.61851.31

Ota H, Tamura H, Itabashi R, Yazawa Y, Nakamura Y, Hisamatsu K, Takamatsu M, Endo H, Niizuma K, Enomoto Y, Nagasaka T, Kajita K, Watanabe M, Yoshimura S, Yuan C (2018) Quantitative characterization of carotid plaque components using MR apparent diffusion coefficients and longitudinal relaxation rates at 3T: a comparison with histology. J Magn Reson Imaging JMRI 48:1657–1667. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.26216

Lovett JK, Gallagher PJ, Hands LJ, Walton J, Rothwell PM (2004) Histological correlates of carotid plaque surface morphology on lumen contrast imaging. Circulation 110:2190–2197. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000144307.82502.32

Redgrave JN, Gallagher P, Lovett JK, Rothwell PM (2008) Critical cap thickness and rupture in symptomatic carotid plaques: the oxford plaque study. Stroke 39:1722–1729. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.507988

Clarke SE, Hammond RR, Mitchell JR, Rutt BK (2003) Quantitative assessment of carotid plaque composition using multicontrast MRI and registered histology. Magn Reson Med 50:1199–1208. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.10618

Xie Y, Yu W, Fan Z, Nguyen C, Bi X, An J, Zhang T, Zhang Z, Li D (2014) High resolution 3D diffusion cardiovascular magnetic resonance of carotid vessel wall to detect lipid core without contrast media. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson Off J Soc Cardiovasc Magn Reson 16:67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-014-0067-z

Young VE, Patterson AJ, Sadat U, Bowden DJ, Graves MJ, Tang TY, Priest AN, Skepper JN, Kirkpatrick PJ, Gillard JH (2010) Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging for the detection of lipid-rich necrotic core in carotid atheroma in vivo. Neuroradiology 52:929–936. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-010-0680-y

Kim S-E, Treiman GS, Roberts JA, Jeong E-K, Shi X, Hadley JR, Parker DL (2011) In vivo and ex vivo measurements of the mean ADC values of lipid necrotic core and hemorrhage obtained from diffusion weighted imaging in human atherosclerotic plaques. J Magn Reson Imaging JMRI 34:1167–1175. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.22736

Qiao Y, Ronen I, Viereck J, Ruberg FL, Hamilton JA (2007) Identification of atherosclerotic lipid deposits by diffusion-weighted imaging. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27:1440–1446. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.141028

Yao B, Yang L, Wang G, Shi H, Wang S, Li H, Chen W, Chan Q (2016) Diffusion measurement of intraplaque hemorrhage and intramural hematoma using diffusion weighted MRI at 3T in cervical artery. Eur Radiol 26:3737–3743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-015-4149-6

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The study received fund from the Institute Technical Development Fund for MRI examinations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AA contributed to methodology, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, and data curation. AAY helped in conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, reviewing and editing, validation, and funding acquisition. PNS was involved in conceptualization, writing—reviewing and editing, and validation. DN and SP performed investigation, visualization, and validation. JV performed reviewing and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Institutional Ethical Approval was obtained. Consent to participate was obtained as written informed consent from all participants.

Consent for publication

Appropriate consents for publishing the clinical and imaging details of the patient were obtained.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visithttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alex, A., Ayyappan, A., Valakada, J. et al. Role of diffusion-weighted imaging in carotid plaque vulnerability assessment. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med 53, 124 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43055-022-00776-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43055-022-00776-2