Abstract

This paper investigates the factors associated with foreign direct investment “surges” and “stops”, defined as sharp increases and decreases, respectively, of foreign direct investment inflows to the developing world and differentiated based on whether these events are led by waves in greenfield investments or mergers and acquisitions. Greenfield-led surges and stops occur more frequently than mergers-and-acquisitions-led ones and different factors are associated with the onset of the two types of events. Global liquidity is the factor significantly and positively associated with a surge, regardless of its kind, while a global economic growth slowdown and a surge in the preceding year are the main factors associated with a stop. Greenfield-led surges and stops are more likely in low-income countries and mergers-and-acquisitions-led surges are less likely in resource-rich countries than elsewhere in the developing world. Global growth accelerations and increases in financial openness, domestic economic and financial instability are associated with mergers-and-acquisitions-led surges but not with greenfield-led ones. These results are particularly relevant for developing countries where FDI flows are the major type of capital flows and suggest that developing countries’ macroeconomic vulnerability increases following periods of increased global liquidity. As countries develop they typically become more exposed to merger-and-acquisition-led surges, which are more likely than greenfield-led surges and stops to be short-lived and associated with domestic macroeconomic policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Foreign direct investment (FDI) flows rose dramatically over the past three decades. Prior to 1985 the growth rate of FDI flows was comparable to that of world trade and output, but after this period FDI flows grew at a much faster pace than either world trade or world output.Footnote 1 FDI flows to the developing world also increased rapidly, although the developed countries generally received more FDI flows than the developing ones and host the majority of the inward FDI stock (UNCTAD 2011). Importantly, the volatility of FDI flows has increased tremendously over the past decades, especially in developing countries (Goldstein and Razin 2006; Neumann et al. 2009). Despite the fact that FDI is regarded as one of the most stable types of capital flows (Lipsey 2001; Albuquerque 2003; Broto et al. 2011), there have been distinct waves of FDI since the 1980s with corresponding surges and stops (Andrade et al. 2001).

This paper investigates the nature and determinants of FDI “stops” and “surges”, defined as sharp increases and decreases, respectively, of gross FDI flowsFootnote 2 to the developing world and differentiated based on whether these events are led by waves in greenfield investments (GF) or mergers and acquisitions (M&A). The study of FDI surges and stops to developing countries is warranted since FDI volatility has been associated with declining long-run economic growth (Lensink and Morrissey 2006). There is also the long-standing concern that sudden stops and surges in foreign capital flows might contribute to and arise as a result of macroeconomic volatility (Calvo et al. 2006) and crises (Reinhart and Reinhart 2009; Furceri et al. 2012) as well as complicate macroeconomic management in developing economies. Abiad et al. (2011) and Cowan and Raddatz (2011), for instance, point to a connection between sudden stops and credit market imperfections.

In this paper we explore the incidence and determinants of FDI surges and stops by mode of entry. Several studies compare different types of financial flow events (e.g., Sula 2010; Cardarelli et al. 2010; Agosin and Huaita 2012; Forbes and Warnock 2012; Furceri et al. 2012; Ghosh et al. 2012), but to our knowledge, none looks separately at the incidence and determinants of GF-led and M&A-led stops and surges in FDI flows to the developing world. The distinction is important for a number of reasons. The two types of FDI flows occur for different reasons and have different effects, characteristics, and incidence.Footnote 3 GF investment inflows finance the construction of new facilities which augment the stock of physical capital and thus expand the production capacity in countries, creating new jobs and increasing market competition (Mattoo et al. 2004). M&As predominantly involve a change in ownership via the purchase of existing assets, although they might result in a more efficient allocation of resources (Kim 2009; Wang and Wong 2009; Harms and Méon 2012).Footnote 4 Importantly, whereas most global FDI waves have been associated with an increase in mergers and acquisitions (M&A) (Brakman et al. 2006), the extent to which greenfield (GF) investments contribute to surges and stops in FDI in developing countries remains unclear. It is, however, important to explore this question in the context of developing countries because GF investments dominate FDI flows to the developing world (Markusen and Stähler 2011; UNCTAD 2012), especially in resource-rich countries where local companies often have privileged access to the resources and, hence, host country government policies encourage GF investments into joint ventures. It is also true in low-income countries where large labor cost differentials between the home and host countries and the absence of attractive corporate assets make GF FDI more likely as an entry mode.Footnote 5 According to Razin and Sadka (2006) the existence of fixed setup cost of new investments introduces two margins of FDI decisions—an intensive one, associated with determining the magnitude of the FDI flow and an extensive one, determining whether to make a new investment. Their theory explains how shocks may have differential impact on the two margins and the two types of FDI flows.

Understanding the role played by the mode of entry in the incidence of FDI surges and stops is valuable in the context of rising FDI flows to the developing world. As shown in Albuquerque (2003), the share of FDI in total foreign equity flows is larger for developing countries than for developed countries, an empirical regularity explained by Goldstein and Razin (2006) with the high production costs in developed economies which imply that it is more beneficial to incur the fixed costs associated with FDI in developing countries than in developed ones. As FDI flows have become an important and often dominant source of finance in developing countries, concerns have grown that economic growth and macroeconomic stability might be harmed in countries exposed to extreme fluctuations of these flows (Lensink and Morrissey 2006; Herzer 2012).

The paper is related to the broader literature on net capital flows, which are volatile, pro-cyclical, and, during crises, prone to large “sudden stops,” defined as sharp slowdowns in net capital inflows. The literature originated with Calvo (1998) and broadened to include different conditions as well as the opposite events such as “surges”, defined as sharp increases in net capital flows (Reinhart and Reinhart 2009).Footnote 6 However, this paper studies the behavior of gross FDI flows to developing countries as we are interested in surges and stops due to actions of foreigners. Cowan et al. (2008) and Rothenberg and Warnock (2011) make the point that measures of “sudden stops” constructed from data on net inflows are not able to differentiate between stops that are due to the actions of foreigners and those due to locals fleeing the domestic markets. In addition, Broner et al. (2013) show that gross capital flows are pro-cyclical and are larger and more volatile than net capital flows.

While Levchenko and Mauro (2007) show that FDI is the least volatile type of financial flows, when the average size of net or gross flows is taken into account, they also insist that fluctuations in FDI flows should not be ignored due to the large share of these flows in net capital flows to emerging and developing economies. This paper shows that FDI surges and stops in the developing world are not rare eventsFootnote 7 and therefore are worth an in-depth look. Specifically, the paper contributes to the literature in the following ways. First, we build a database of FDI surges and stop episodes, distinguished based on the dominance of the mode of entry. Using this database, which covers the period from 1991 to 2010 and includes 95 developing economies, we document the incidence of sudden stops and surges by mode of entry, region, and resource status of the receiving economy. Second, we identify the factors associated with FDI surges and stops by mode of entry (i.e. GF-led and M&A-led surges and stops).

Our approach yields different results from previous studies on surges and stops in FDI flows which do not differentiate between these events based on the mode of entry (e.g., Dell’Erba and Reinhardt 2012). We show that different factors are associated with the onset of GF-led and M&A-led FDI surges and stops. Global liquidity is the only common factor associated with a surge, regardless of its type, while a global growth slowdown and a surge in the preceding year are the main factors associated with a stop. GF-led sudden stops and surges are more likely in lower income and resource-rich countries than elsewhere. Policies aimed at increasing financial openness are enablers of M&A-led surges, which are also more likely during periods of global growth accelerations and domestic economic and financial instability. The results are policy relevant as we show that different types of developing countries tend to be vulnerable to different types of FDI surges and stops. As developing countries transition from low-income to middle-income status they typically become more exposed to M&A-led extreme events which are more likely than GF-led extreme events to be short-livedFootnote 8 and associated with domestic macroeconomic policies. Low-income and resource-rich countries are more exposed to GF-led surges and stops which are associated mainly with external factors. Thus, these groups of countries are particularly susceptible to global shocks and should adopt macroeconomic policies that address these challenges.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The next section defines FDI surges and stops and presents information on the types and frequency of such surges. In Sect. 3, we turn attention to the empirical models that associate GF-led and M&A-led surges and stops with key determinants, the discussion of the econometric results, and the robustness checks. Section 4 summarizes the findings and offers concluding remarks.

2 GF-led and M&A-led FDI surges and stops: definitions and incidence

Using UNCTAD data on gross FDI inflows from the World Investment Report (UNCTAD 2011) and building on the work by Calvo et al. (2004), Reinhart and Reinhart (2009), and Forbes and Warnock (2012), we define a surge episode as an increase in inflows in a given year that is more than one standard deviation above the country-specific (5-year rolling) average.Footnote 9 The surge episode begins when the FDI-to-GDP ratio increases more than one standard deviation above its rolling mean and ends when the FDI-to-GDP ratio falls below one standard deviation above its rolling mean.Footnote 10 In addition, we pose a restriction to the definition of an FDI surge in that the increase in the FDI-to-GDP ratio should fall within the top 25th percentile of the entire sample’s FDI-to-GDP ratio growth. This not only ensures that the increase in FDI inflows is substantial, but also that only large surges by international standards are included in our definition of a surge (Ghosh et al. 2012).

This approach combines the two main empirical strategies present in the literature on surges and stops. One involves looking at deviations from the mean while the other requires factoring in minimum threshold values. Stops are defined in a symmetric way, with a stop episode defined as a decline in inflows in a given year that is more than one standard deviation below the rolling average. The stop episode starts when the ratio of FDI to GDP declines more than one standard deviation below its rolling mean and ends when the ratio increases above one standard deviation below its mean. We impose similar restrictions on stops as on surges.

To identify whether a FDI surge or a stop can be mainly attributed to an increase in M&A activity or GF investments, we use Thompson ONE Source data on M&A inflows, available from 1990 onwards. Following Calderón et al. (2004), Wang and Wong (2009), and Bogach and Noy (2015), GF FDI is defined as the difference between gross FDI and M&A inflows. Using this information, we assess whether a surge in a given year is dominated by an increase in M&A activity or by an increase in GF investments. A surge is M&A-led when more than half of the increase in FDI can be attributed to an increase in M&A activity. Likewise, a surge is GF-led when more than half of the increase in FDI can be attributed to an increase in GF investments.

As indicated by Calderón et al. (2004), there are several potential problems with combining aggregate FDI inflow data with M&A data. First, calculating GF FDI as the residual of FDI and M&A may possibly pollute the data with some international transactions that are not GF FDI. Second, FDI flows are recorded on a transaction basis, while M&As are recorded at the time of an official announcement or closure of a deal in the press. Therefore, a FDI surge in a given year could be M&A-led even if there is not a substantial increase in M&A flows in the current year, but there is a substantial increase in M&A flows without a FDI surge in the previous year. We control for this issue by examining all FDI surge episodes and the shares of M&A flows in total FDI flows in the year before and during the FDI surge. There were only few instances in which there was no increase in M&A in the current year, but there was a considerable increase in M&A flows without an FDI surge in the previous year. Therefore, only in these few instances we had to reclassify the type of a surge from GF-led to M&A-led one.

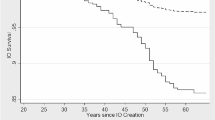

Figure 1 on FDI surges and stops in Algeria illustrates how such events are identified. The left panel of Fig. 1 assesses the first condition, namely that we speak of a surge if the FDI-to-GDP ratio increases more than one standard deviation above its 5 year rolling mean. We see that in Algeria this is the case in several years in the mid-1990s and the early and late 2000s. Likewise, a stop is identified when the FDI-to-GDP ratio decreases more than one standard deviation below its 5 year rolling mean. This is the case in 1992, 2003 and 2010. However, in order to qualify for a surge, the increase should fall within the top 25th percentile of the entire sample’s FDI-to-GDP ratio growth, meaning an increase of at least 0.82% points, marked by the top horizontal line in the right panel of Fig. 1. Likewise, in order to qualify for a stop, the increase should fall within the bottom 25th percentile of the entire sample’s FDI-to-GDP ratio growth, meaning a decrease of at least 0.55% points, marked by the bottom horizontal line in the right panel of Fig. 1. This means that Algeria experienced a FDI surge only in 2001, while in 1999, 2003, and 2010 it experienced a FDI stop. As can also be observed from right panel of Fig. 1, Algeria received few M&A flows. Hence, all surges and stops in Algeria are classified as GF-led.

In total, the 95 developing economies in the sample experienced 264 surge-episodes during the period 1991–2010, of which 207 were led by a surge in GF investments and 57 were dominated by a surge in M&A activity (see Appendix A1 of Supplementary material).Footnote 11 The unconditional probability of experiencing a surge in GF investments and M&A activity was 11.7 and 3.2%, respectively. All countries in the sample except Bangladesh experienced at least one surge. However, whereas the majority of countries (87%) experienced at least one GF-led surge in the period under research, the percentage of countries that experienced at least one M&A-led surge was much lower (43%).

Although M&A flows are much more volatile than GF flows in absolute terms,Footnote 12 GF-led FDI surges outnumber M&A-led FDI surges in developing countries: around 80% of the FDI surges in developing economies can be attributed to an increase in GF FDI. Regions with either a high share of resource-rich or low-income countries or both such as the Middle East and North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa, where GF investments represent a large share of FDI flows, have had the highest occurrence of GF-led FDI surges (Table 1). In resource-rich countries, governments encourage GF investments as local firms typically have privileged access to the resources. In low-income economies, large labor cost differentials between the home and host economies make GF FDI more likely as an entry mode. Regions with relatively strong links to global financial markets have had the lowest incidence of GF-led FDI surges and the highest incidence of M&A-led FDI surges. In addition, our analysis suggests that some countries experience more FDI surges than others and FDI surges occur at different times in different developing countries and usually last only a year. They were most prevalent in Europe and Central Asia and the Middle East and North Africa in the mid-2000s, in East Asia and Pacific and Sub-Saharan Africa in the late 1990s and late 2000s, and in Latin America and Caribbean in the mid-1990s.

We identify FDI stops in a symmetric way. The 95 developing economies in the sample experienced 273 stop-years during the period 1991–2010, of which 217 were GF-led stops and 56 were M&A-led stops (see also Appendix A1 of Supplementary material). The unconditional probability of experiencing a GF-led stop was 12.3%, while that for an M&A-led stop was 3.2%. All countries in the sample experienced at least one stop-year and most stops were GF-led. Yet, M&A-led surges are significantly more frequently followed by a stop in the next year (51%) than GF-led surges (36%) (p value for the Fischer’s exact test < 0.01). This suggests that M&A-led surges are more likely to be short-lived and followed by a stop than GF-led events.

Although at the global level the unconditional probability of experiencing a surge is similar to that of a stop, the occurrence of surges varies by region and over time. Stops are more frequent in Europe and Central Asia than in the other world regions and least frequent in lower income developing countries, but differences between different country groups are never statistically significant.Footnote 13 As in the case of FDI surges, stops occur at different times in different developing countries and most of them last only a year.

3 GF-led and M&A-led FDI surges and stops: analysis and determinants

3.1 Conceptual approach and variables

We inform the selection of variables that might be associated with a FDI surge or a stop by drawing on the literature on sudden stops and bonanzas. As in the conceptual framework of Forbes and Warnock (2012), the probability of a GF-led and M&A-led surge or stop depends on three sets of factors—global, contagion (regional), and domestic (Calvo et al. 1996; Fernandez-Arias and Montiel 1996; Dell’Erba and Reinhardt 2012; and Forbes and Warnock 2012).Footnote 14 Hence, to examine the role of these global, contagion, and domestic factors in the conditional probability of having a GF-led or M&A-led FDI surge or a stop, we estimate the model:

The variable ε it is an indicator of the occurrence of an event in country i and year t and is equal to one of six episode dummy variables defined as follows. The first one, s it , assumes the value 1 if there is a FDI surge, either GF-led or M&A-led one, in country i and year t. In all other cases, s it is 0. The dummy variable, h it , equals 1 if a country i is experiencing a GF-led surge in a given year t and 0 otherwise. Finally, the dummy variable m it is 1 in the case of an M&A-led surge in a given year t and country i, and 0 otherwise. In a similar fashion, three dummy variables for stops are defined: one for GF-led FDI stops, one for M&A-led FDI stops, and one for FDI stops, regardless of their kind (GF-led or M&A-led). G is a vector of variables capturing global factors, R is a vector of variables capturing regional factors, and D is a vector of variables capturing domestic factors.

Since surges and stops occur irregularly, ψ(.) is asymmetric and, therefore, as in Forbes and Warnock (2012), we estimate Eq. (1) using the complementary logistic regression. It assumes that ψ(.) is the cumulative distribution function (cdf) of the extreme value distribution. We estimate the model separately for the different types of events, but use seemingly unrelated estimations that allow for cross-episode correlations in the error terms, estimated with clustering of standard errors at the country level. The variables representing domestic stop or surge, GDP per capita, and natural resources are lagged by one year, and the latter two are winsorized at the 1% level.Footnote 15 Although we attempt to deal with endogeneity concerns with regard to the domestic factors of interest by using lagged dependent variables, the serial correlation present in the data prevents us from drawing causal inferences and our results should be interpreted as conditional associations, rather than causal relationships.

Economic developments in developed markets, which are the primary source of this type of finance, trigger big fluctuations in FDI flows to developing countries (Aleksynska and Havrylchyk 2013). Therefore, following Forbes and Warnock (2012), we include several global factors, including global risk, global liquidity, and global growth. Global risk is a volatility measure given by the VXO index of the Chicago Board Options Exchange. Global liquidity measures the availability of finance in global markets and is given by the sum of the change in the following two ratios – the ratio of stock market capitalization to GDP and the ratio of domestic private sector credit to GDP (Beck et al. 2000).Footnote 16 The size of the financial market is expected to be positively related to the ability to mobilize capital. Global growth measures the real growth of the world economy and is obtained from the World Development Indicators.

We also include measures capturing regional contagion or the extent to which surges or stops occurred in the region of the country experiencing the surge. The indicator used to measure this factor is the share of countries in the same macro region which experienced a surge in the preceding year (see also Dell’Erba and Reinhardt 2012).

The domestic set of factors include experiencing a surge in the preceding year, experiencing a stop in the preceding year (see also Sula 2010),Footnote 17 per capita GDP, natural resource rents as a share of GDP, and the change in the following set of variables—trade and financial openness, economic and financial stability, and political stability (see Appendix A2 of Supplementary material).

The association between global factors and the two types of surges and stops is unlikely to differ qualitatively; global liquidity tends to encourage FDI flows in general. However, we expect to see differences in the magnitude and significance of the association as global factors are just a few among a number of other factors that affect FDI flows and the relative importance of these factors differs across countries and across modes of entry, as suggested by Razin and Sadka (2006). We expect M&A-led surges and stops to be more prevalent in higher income developing economies (Nocke and Yeaple 2008; Qiu and Wang 2011) because of the presence of attractive corporate assets in terms of quality of inputs and technologyFootnote 18 and a narrower gap in production costs between the destination and the source country.Footnote 19 A large price differential between the home and host countries might make GF investments more likely as an entry mode in lower income developing economies (Razin and Sadka 2006). These differentials are needed to offset the higher setup costs associated with the construction of new facilities relative to the acquisition of existing ones. Investments in resource-intensive industries also usually take the form of GF FDI. The reason for this is that local companies often have privileged access to these natural resources and, hence, host country governments prefer joint ventures in the form of GF FDI (Demirbag et al. 2008).

M&A-led surges and stops are also more likely in riskier and uncertain macroeconomic environments because of the existence of discounts on the prices of existing assets (Buiter et al. 1998). Such events have been associated with fire-sale FDI during the Latin American and Asian financial crises of the 1990s (Krugman 2000; Aguiar and Gopinath 2005). M&A-led surges and stops have been encouraged by capital market imperfections that result in undervaluations of firm assets, sales of assets at unrealistic prices, and stripping of firms for purely financial gains. Changes in financial openness in particular might have an effect on the likelihood of an M&A-led surge or stop. Furthermore, the existence of capital controls in the form of restrictions on foreign ownership and short-selling may limit possibilities for the earlier-mentioned fire-sale FDI.Footnote 20 There seems to be a strong political preference for GF investments, which are perceived to be more beneficial than M&As (Heinemann 2012). Domestic unrest can also deter some types of FDI or trigger the pullout of investors from some markets (Schneider and Frey 1985). Still, results from econometric studies are ambiguous about the relationship between the degree of political stability in a country and stops in FDI inflows (Salomon and Ruiz 2012).

The source for data on GDP, trade, and natural resource rents is the World Bank’s World Development Indicators. Financial openness is represented by the Chinn and Ito (2008) capital account openness index. The International Country Risk Guide is the source for the economic, financial, and political stability measures. Definitions and sources for the independent variables are presented in Appendix A2 of Supplementary material, while descriptive statistics can be found in Appendix A3 of Supplementary material. Alternative definitions of surges and stops and definitions of additional variables are presented in Appendix B of Supplementary material.

3.2 Econometric results

The results from the complementary logistic regressions presented in Table 2 suggest that in general FDI surges are difficult to predict.Footnote 21 The baseline regressions have low pseudo R2 varying between 3 and 10% of the observed variance.Footnote 22 Stops appear easier to predict in that the pseudo R2 varies between 10 and 34%. This difference can be attributed mainly to the fact that a surge in the preceding year is a good predictor of a FDI stop, but not vice versa. Hence, it can be inferred that surges are followed by stops. At the same time, a FDI surge in the preceding year is not a good predictor of a surge and a FDI stop in the preceding year is not a good predictor of a stop.

3.2.1 FDI surges

Global liquidity is associated positively with a FDI surge, regardless of its kind. Although global liquidity is only significantly correlated with the probability of a GF-led surge (Table 2), the effect of global liquidity on the likelihood of a GF-led surge does not significantly differ from the effect of global liquidity on the likelihood of an M&A-led surge (χ2 = 0.08, p = 0.77). Furthermore, the effect of global liquidity on the likelihood of an M&A-led surge becomes significant under alternative definitions of a surge (Appendix Tables B3 of Supplementary material),Footnote 23 alternative definitions of a resource-rich economy, economic, financial and political stability (Appendix Tables B7 of Supplementary material), additional control variables (Appendix Tables B11 of Supplementary material), and alternative estimation techniques (Appendix Tables B14 and B15 of Supplementary material). Overall, these results suggest that loosening of global credit conditions in response to global financial crises tends to increase the frequency of FDI surges in developing countries. These results are in line with earlier findings of Di Giovanni (2005) and Baker et al. (2009) that the availability of cheap financial capital stimulates the expansion of multinational activity.

Regional contagion increases the probability of a surge, but not of a stop (Table 2). The result is robust when we use random effects probit, which allows for country-specific unobserved heterogeneity (Table 3), complementary logistic regression with fixed effects (Appendix Table B14 of Supplementary material), and multinomial logistic regression (Appendix Table B15 of Supplementary material). The conclusions that can be drawn from these estimations are to a large extent identical to the ones from a seemingly unrelated estimated complementary logistic regression with cluster-robust standard errors presented in Table 2. Likewise, considering a more restricted sample of “sustainable” surges (Table 4), which excludes surges followed by stops, did not lead to substantially different results. However, when we only focus on “sustainable” M&A-led surges and “relentless” stops (stops not followed by a surge), the effect of regional contagion on the probability of a surge becomes insignificant.

There are pronounced differences with regard to the factors that predict the onset of M&A-led and GF-led surges. Global growth is positively and significantly correlated with the incidence of M&A-led surges and FDI-surges in general, but not with GF-led surges. The difference in effect sizes between M&A-led and GF-led surges was statistically significant (χ2 = 16.56, p < 0.01). The result is robust across different estimation strategies, alternative definitions of surges, other variables’ definitions, and additional control variables (see results in Table 3, Appendix Tables B1 and B3, Appendix Tables B5 and B7, and Appendix Tables B9 and B11 of Supplementary material). In the case of M&A-led surges, the result is in line with the fact that the two most recent global FDI and M&A waves took place during periods of strong economic growth, and their ends coincided with global downturns. In the case of GF-led surges, it reflects the fact that firms are often driven to invest in operations located in developing countries as a cost cutting measure and not necessarily during periods of strong global growth. However, when we only focus on sustainable surges (Table 4), we find that global growth is a significant predictor for sustainable GF-led surges.

A country with lower per capita income level is significantly more likely to experience GF-led surges (Table 2). In contrast, M&A-led surges are significantly more likely in countries with higher per capita incomes. The difference in the effect of per capita income levels on the likelihood of having a GF-led versus M&A-led surge is statistically significant (χ2 = 13.10, p < 0.01). These results are robust to alternative estimation techniques (Table 3), alternative specifications (Appendix Tables B9 and B11 of Supplementary material), and different definitions of a surge (Appendix Tables B5 and B7 of Supplementary material), except in the case of the complementary logistic regression model with fixed effects. In this case, since GDP per capita is relatively stable over the sample period, its effect is picked up to some extent by the fixed effects, which explains the large standard errors in the fixed effects estimation (Appendix Table B14 of Supplementary material).

Resource-rich countries are less likely to incur an M&A-led surge. This result is robust across most but not all estimation techniques, variable definitions, and additional control variables. It is not robust in the case of the fixed effects estimation and alternative definitions of a surge. However, the difference in the effect sizes on the likelihood of the two types of surges is statistically significant (χ2 = 5.01, p = 0.025) and this result holds when we replace the natural resource variable with a dummy variable that takes the value 1 if a country is hydrocarbon or mineral-rich as defined by the IMF (Appendix Tables B5 and B7 of Supplementary material; χ2 = 7.26, p < 0.01).

In line with the fire-sale FDI hypothesis of Krugman (2000) and Aguiar and Gopinath (2002) and as shown by Bogach and Noy (2015), M&A-led surges are significantly more likely in countries which experience deterioration in economic and financial stability. Although an improvement in economic and financial stability tends to be positively associated with the probability of a GF-led surge, the variable is not significant in the baseline model and alternative tests. These results are robust to changes in the model specification, estimation technique, and variables definitions. The difference between the effects of changes in economic and financial stability on the likelihood of the two types of FDI surges is statistically significant (χ2 = 7.83, p < 0.01) and becomes more pronounced under stricter definitions of a surge. The findings are supported by the results when additional control variables related to changes in domestic macroeconomic economic conditions are added to the model (Appendix Tables B9 and B11 of Supplementary material). A decrease in the exchange rate and an increase in the inflation rate are positively associated with the probability of M&A-led surges, but not of GF-led surges. This difference in effect size of the exchange rate variable is statistically significant (χ2 = 9.35, p < 0.01).

A decrease in capital controls (i.e. increase in financial openness) is associated with a higher probability of an M&A-led surge, but not with a higher probability of a GF led surge (Table 2). This finding is in line with the idea that there is a strong political preference for GF FDI and capital controls particularly affect FDI in the form of M&As. The result is robust across different definitions of a surge and independent variables, as well as additional controls and alternative estimation techniques. However, no significant differences are found when estimating the model using the random probit estimator (Table 3) and the difference between the effects of changes in financial openness on the probability of the two types of FDI surges is not statistically significant in most specifications. Finally, global risk and changes in political stability do not affect the likelihood of an FDI surge regardless of its type in nearly all specifications, although estimation of multinomial logistic regression suggests that global risk increases the probability of observing either a surge or a stop versus observing neither a surge nor a stop (Appendix Table B15 of Supplementary material).

3.2.2 FDI stops

An FDI surge in the preceding year is the only significant and robust predictor of an FDI stop, regardless of its kind (Table 2). This result is in line with the recent findings of Agosin and Huaita (2012) who show that the best predictor of a sudden stop is a preceding capital boom, where stops are downward overreactions to sharp preceding positive overreactions. Tightening of global credit conditions diminishes the frequency of FDI surges, but conditional on a surge in the previous year do not necessarily have a contemporaneous effect on the likelihood of FDI stops. However, since global liquidity is significantly associated with FDI surges, and a surge is significantly associated with a stop in the next period, global liquidity is associated with both FDI surges and stops.

A decline in global growth has a significant and positive effect on the likelihood of a FDI stop, regardless of its kind, where the difference in effect sizes between the two modes of entry is not statistically significant (χ2 = 0.79, p = 0.38). This result, however, loses its significance under stricter definitions of stops, be they GF-led or M&A-led (Appendix Tables B2 and B4 of Supplementary material) and alternative definitions of a stop with the multinomial logistic regression (Appendix Table B15 of Supplementary material).

GF-led and M&A-led FDI stops are, on average, more likely in poorer and richer countries, respectively. The effect itself is not significant, but the difference in effect sizes is statistically significant (χ2 = 4.57, p = 0.033) and becomes pronounced under stricter definitions of FDI stops (Appendix Tables B2 and B4 of Supplementary material). This difference in effect sizes generally holds under alternative estimation methods and variable definitions and when additional variables are included.

The frequency of FDI stops is not higher in resource-rich countries than elsewhere in the world. Resource-rich economies appear to be more likely to have GF-led episodes and less likely to have M&A-led episodes, but these average effects are not significant across a range of alternative model and variables’ specifications. Moreover, the difference in effect sizes of natural resources on GF-led and M&A-led stops is not statistically significant (χ2 = 1.70, p = 0.192) in the baseline model in Table 2 as well as in the model using the alternative definition of natural resources (Appendix Tables B6 and B8 of Supplementary material; χ2 = 1.29, p = 0.257).

Removal of capital controls increases the probability of an M&A-led stop, but not of a GF-led stop. The difference in effect sizes is statistically significant (χ2 = 7.05, p < 0.01) and holds when we control for changes in trade openness and tariffs (Appendix Tables B10 and B12 of Supplementary material), but this result becomes less pronounced under stricter definitions of a stop (Appendix Tables B2 and B4 of Supplementary material). Global riskFootnote 24 and changes in political, economic, and financial stability do not affect the likelihood of a FDI stop, regardless of its type and model specification.

3.3 Sensitivity analysis

This section provides an overview of the most important results from the sensitivity analysis that are presented in Appendix B of Supplementary material, but that are not discussed in the previous paragraph. The estimations which use alternative variable definitions (Appendix Tables B5–B8 of Supplementary material) and additional control variables (Appendix Tables B9–B12 of Supplementary material) do not yield very different results.

Differences with the baseline regression under different definitions of FDI surges and stops (Appendix Tables B1–B4 of Supplementary material) are most pronounced. Under the strictest definition the number of surges and stops falls down to 143 (8.0% of the all country-years) and 108 (6.1% of all the country-years), respectively. Compared to the baseline regressions, the effect of global growth on the likelihood of GF-led and M&A-led stops, the effect of regional contagion on the likelihood of GF-led surges, and the effect of a stop in the preceding year on GF-led stops lose their significance under stricter definitions of a surge or a stop. In addition to the differences described above, a decrease in political stability has a positive and significant effect on the likelihood of a GF-led surge under some of the stricter definitions of a surge. This result can be explained by the fact that some firms try to take advantage of new opportunities that arise through changes in political regimes and reap the benefits in conflict locations through first mover advantages or market power. In particular, firms in the primary sector (which mainly enter through GF FDI) would be less deterred by a decrease in political stability because activities in this sector are bound by physical geography and risk-adjusted rents are higher (Burger et al. 2015).

Our findings are not driven by lumpiness or the concentration of capital investments in only a few projects. The observation that surges have a 1-year duration and are followed by a stop can be the result of rare large projects such as building a manufacturing plant or developing a gas or oil field. If this were to be true, the analysis of sudden stops would be less interesting. Using data obtained from the World Investment Report 2015 on the number of M&A projects by country and year for the period 1991–2010 (unfortunately adequate GF data were not available), it find that there is a positive association between the number of M&A investments a country receives and the likelihood of a M&A-led surge. In other words, the years characterized by a M&A surge are also years in which the country receives a more than average number of M&A investments compared to other years (Appendix Tables B13 of Supplementary material). On the contrary, there is no relationship between the number of M&A projects and the incidence of a GF-led surge, GF-led stop, and M&A-led stop. Hence, our results on the determinants of surges and stops do not seem to be driven by the lumpiness of investments.

4 Concluding remarks

This paper investigates the factors associated with FDI surges and stops, differentiated based on whether these events are led by waves in GF investments or M&As. The focus on this topic is warranted because during the past decade there has been a significant increase in FDI flows to developing countries but the rise has not proceeded in a smooth fashion, prompting concerns about sudden stops even in countries where FDI inflows dominate capital flows. Furthermore, whereas most global FDI waves have been associated with an increase in M&As, it is not clear to what extent GF investments have contributed to FDI surges and stops in developing countries. It is important to answer this question because GF investments dominate FDI flows to the developing world, especially in resource-rich and low-income countries, and as shown in the paper, GF-led surge and stop episodes occur more frequently than M&A-led ones.

This paper contributes to the literature by constructing a database of FDI surges and stops episodes, distinguished based on the dominance of the entry mode. We use this database to document the incidence of FDI surges and stops by mode of entry, region, and resource status. Using this database, we analyze the factors associated with GF-led and M&A-led surge and stop events and show that the two types of surges and stops have different incidence and determinants, and therefore must be studied separately.

Our analysis shows that GF-led surges and stops occur more frequently than M&A-led ones. Global liquidity is the factor significantly and positively associated with a surge, regardless of its type, while a global growth slowdown and a surge in the preceding year are the main factors associated with a stop. GF-led stops and surges are more likely in low-income countries and mergers-and-acquisition-led surges are less likely in resource-rich countries than elsewhere in the developing world. Policies aimed at increasing financial openness are enablers of M&A-led surges, which are also more likely during periods of global growth accelerations and domestic economic and financial instability. The results are particularly relevant to developing countries where FDI flows are the major type of capital flows; they suggest that macroeconomic vulnerability increases following periods of increased global liquidity and growth, especially in low-income countries. As countries develop they typically become more exposed to M&A-led surges which are more likely than GF-led surges to be short-lived and associated with domestic macroeconomic policies and political conditions.

Notes

The growing importance of FDI flows has spurred burgeoning literatures on the causes and effects of FDI in international and financial economics, international business, and economic geography. See Barba Navaretti and Venables (2004), Blonigen (2005), and Brakman et al. (2006) for overviews of these literatures.

These flows include equity capital, reinvestment of earnings, other long-term capital, and short-term capital less disinvestments.

However, both modes are associated with increases in aggregate productivity.

Our focus on the developing world is also motivated by the study of Blonigen and Wang (2005) who show that the determinants of FDI flows to developing countries differ from those to developed ones.

All developing countries experienced at least one such event during the period of investigation and most countries experienced multiple FDI surges and stops.

We test whether M&A surges are short-lived because of lumpiness or the concentration of capital investments in only a few projects and rule these possibilities out.

We use deviations in FDI-to-GDP ratios rather than absolute FDI flows as it is the appropriate approach in a cross-country setting, although we recognize that in a small number of cases there might be ‘abnormal’ surges and stops driven by extreme changes in GDP. In our database there are only 5.5% of ‘abnormal stops’ resulting from increases in GDP that coincide with increases in FDI flows and 9.1% of ‘abnormal surges’ that occur due to a decline in GDP. Our results are robust to the exclusion of these ‘abnormal’ FDI surges and stops.

Some countries had to be excluded from the empirical analysis because explanatory variables for these countries were not available.

In absolute terms, the average coefficient of variation for M&A flows was 4.00, the coefficient of variation for GF flows was only 0.82. The average coefficient of variation is based on the mean value for the coefficients of variation for all countries in the sample. In relative terms, the volatility of M&A-to-GDP ratios is similar to the volatility of GF-to-GDP ratios.

This conclusion is based on a Fischer’s exact test.

Forbes and Warnock (2012) review several large empirical and theoretical bodies of literature to identify a parsimonious list of factors that might be associated with capital flow waves. They group these factors into global factors such as global risk, liquidity, interest rates, and growth; contagion factors through trade, finance and geographic proximity linkages; and domestic factors such as a country’s financial market development, integration with global financial markets, fiscal position, and growth shocks.

Other estimation methods, including random probit and multinomial logit are used as robustness checks.

See Forbes and Warnock (2012) for a similar operationalization of this variable.

It can be expected that some surges concur with the recovery from a stop in FDI and some stops happen after a sudden surge in FDI.

Foreign firms typically ‘cherry pick’ high quality targets (Bertrand et al. 2012).

Aleksynska and Havrylchyk (2013) estimated that for the period 1996–2007, 56% of all FDI into developing countries originated from developed countries.

Likewise, government interventions against the takeover of domestic companies through cross-border M&A have become more common recently (Heinemann 2012).

Given the large T in the sample, we expect the Nickell bias to be limited in our baseline results, presented in Table 2. We tested for Nickell bias in this baseline specification by examining whether the error term was correlated with the lagged dependent variable of interest and found this to be the case in 2 of the 6 specifications (GF-led surges and GF-led stops). The results do not change when we re-estimate the baseline specification without the lagged dependent variable.

This figure is based on McFadden’s R2.

The increase in the FDI-to-GDP ratio is more than one and a half standard deviation above its rolling mean.

Except for the multinomial estimation (Appendix Table B15 of Supplementary material).

References

Abiad, A., Dell’Ariccia, G., & Li, B. (2011). Creditless recoveries. (IMF Working Paper 11/58). International Monetary Fund.

Agosin, M. R., & Huaita, F. (2012). Overreaction in capital flows to emerging markets: Booms and sudden stops. Journal of International Money and Finance, 31(5), 1140–1155.

Aguiar, M., & Gopinath, G. (2005). Fire-sale foreign direct investment and liquidity crises. Review of Economics and Statistics, 87(3), 439–452.

Albuquerque, R. (2003). The composition of international capital flows: Risk sharing through foreign direct investment. Journal of International Economics, 61, 353–383.

Aleksynska, M., & Havrylchyk, O. (2013). FDI from the South: The role of institutional distance and natural resources. European Journal of Political Economy, 29(March), 38–53.

Andrade, G., Mitchell, M., & Stafford, E. (2001). New evidence and perspectives on mergers. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(2), 103–120.

Baker, M., Foley, C. F., & Wurgler, J. (2009). Multinationals as Arbitrageurs: The effects of stock market valuations on foreign direct investment. Review of Financial Studies, 22(1), 337–369.

Barba Navaretti, G., & Venables, A. J. (2004). Multinational firms in the world economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Levine, R. (2000). A new database on the structure and development of the financial sector. World Bank Economic Review, 14(3), 597–605.

Bertrand, O., Hakkala, K. N., Norbäck, P.-J., & Persson, L. (2012). Should countries block foreign takeovers of R&D champions and promote greenfield entry? Canadian Journal of Economics, 45(3), 1083–1124.

Blonigen, B. A. (2005). A review of the empirical literature on FDI determinants. Atlantic Economic Journal, 33(4), 383–403.

Blonigen, B. A., & Wang, M. (2005). Inappropriate pooling of wealthy and poor countries in empirical FDI studies. In T. Moran, E. Graham, & M. Blomstrom (Eds.), Does foreign direct investment promote development? (pp. 221–243). Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics.

Bogach, O., & Noy, I. (2015). Fire-sale FDI? The impact of financial crises on foreign direct investment. Review of Development Economics, 19(2), 387–399.

Brakman, S., Garretsen, H., Van Marrewijk, C., & Van Witteloostuijn, A. (2006). Nations and firms in the global economy: An introduction to international economics and business. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Broner, F., Didier, T., Erce, A., & Schmukler, S. (2013). Gross capital flows: Dynamics and crisis. Journal of Monetary Economics, 60(1), 113–133.

Broto, C., Díaz-Cassou, J., & Erce, A. (2011). Measuring and explaining the volatility of capital flows to emerging countries. Journal of Banking & Finance, 35, 1941–1953.

Buiter, W., Lago, R., & Rey, H. (1998). Financing in transition: Investing in enterprises during macroeconomic transition. (EBRD Working Paper 35). London: European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

Burger, M., Ianchovichina, E., & Rijkers, B. (2015). Risky business: Political instability and sectoral greenfield foreign direct investment in the Arab world. World Bank Economic Review, 30(2), 306–331.

Calderón, C., Loayza, N., & Servén, L. (2004). Greenfield foreign direct investment and mergers and acquisitions: Feedback and macroeconomic effects. (World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 3192). Washington DC.

Calvo, G. (1998). Capital flows and capital market crisis: The simple economics of sudden stops. Journal of Applied Economics, 1(1), 35–54.

Calvo, G., Izquierdo, A., & Loo-Kung, R. (2006). Relative price volatility under sudden stops: The relevance of balance sheet effect. Journal of International Economics, 69(1), 231–254.

Calvo, G., Izquierdo, A., & Meija, L.-F. (2004). On the empirics of sudden stops: The relevance of balance-sheet effects. (NBER Working Paper 10520).

Calvo, G., Leiderman, L., & Reinhart, C. (1996). Inflows of capital to developing countries in the 1990s. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10(2), 123–139.

Cardarelli, R., Elekdag, C., & Kose, M. A. (2010). Capital inflows: Macroeconomic implications and policy responses. Economic Systems, 34(4), 333–356.

Chinn, M., & Ito, H. (2008). A new measure of financial openness. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, 10(3), 309–322.

Cowan, K., De Gregorio, J., Micco, A., & Neilson, C. (2008). Financial diversification, sudden stops, and sudden starts. In K. Cowan, E. Sebastian, & R. Valdes (Eds.), Current account and external financing: An introduction (pp. 159–194). Central Bank of Chile: Santiago.

Cowan, K., & Raddatz, C. (2011). Sudden stops and financial frictions. (World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5605).

Dell’Erba, S., & Reinhardt, D. (2012). Surfing the capital waves: A sector-level examination of surges in FDI inflows. (Working Paper 11.07). Study Center Gerzensee.

Demirbag, M., Tatoglu, E., & Glaister, K. W. (2008). Factors affecting perceptions of the choice between acquisition and greenfield entry: The case of western FDI in an emerging market. Management International Review, 48, 5–38.

Di Giovanni, J. (2005). What drives capital flows? The case of cross-border M&A activity and financial deepening. Journal of International Economics, 65, 127–149.

Fernandez-Arias, E., & Montiel, P. (1996). The surge in capital inflows to developing countries: An analytical overview. World Bank Economic Review, 10(1), 51–77.

Forbes, K. J., & Warnock, F. E. (2012). Capital flow waves: Surges, stops, flight and retrenchment. Journal of International Economics, 88(2), 235–251.

Furceri, D., Guichard, S., & Rusticelli, E. (2012). Episodes of large capital inflows, banking and currency crises, and sudden stops. International Finance, 15(1), 1–35.

Ghosh, A. R., Kim, J., Qureshi, M. S., & Zalduendo, J. (2012). Surges. (IMF Working Paper 12/22).

Goldstein, I., & Razin, A. (2006). An information-based trade off between foreign direct investment and foreign portfolio investment. Journal of International Economics, 70, 271–295.

Harms, P., & Méon, P.-G. (2012). Good and bad FDI: The growth effects of greenfield investment and mergers and acquisitions in developing countries. (Working Paper).

Heinemann, A. (2012). Government control of cross-border M&A: Legitimate regulation or protectionism? Journal of International Economic Law, 15(3), 843–870.

Herzer, D. (2012). How does foreign direct investment affect developing countries’ growth? Review of International Economics, 20(2), 396–414.

Kaminsky, G., Lizondo, S., & Reinhart, C. (1998). Leading indicators of currency crises. IMF Staff Papers, 45(1), 1–48.

Kim, Y.-H. (2009). Cross-border M&A vs. greenfield FDI: Economic integration and its welfare impact. Journal of Policy Modeling, 31(1), 87–101.

Krugman, P. (2000). Fire-sale FDI. In S. Edwards (Ed.), Capital flows and the emerging economies: Theory, evidence and controversies (pp. 43–59). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Lensink, R., & Morrissey, O. (2006). Foreign direct investment: Flows, volatility, and the impact on growth. Review of International Economics, 14(3), 478–493.

Levchenko, A., & Mauro, P. (2007). Do some forms of financial flows protect from sudden stops? World Bank Economic Review, 21(3), 389–411.

Lipsey, R. E. (2001). Foreign direct investment in three financial crises. (NBER Working Paper No. 8084).

Markusen, J. R., & Stähler, F. (2011). Endogenous market structure and foreign market entry. Review of World Economics, 147(2), 195–215.

Mattoo, A., Olarreaga, M., & Saggi, K. (2004). Mode of foreign entry, technology transfer, and FDI policy. Journal of Development Economics, 75(1), 95–111.

Mendoza, E. (2010). Sudden stops, financial crises, and leverage. American Economic Review, 100(5), 1941–1966.

Neumann, R. M., Penl, R., & Tanku, A. (2009). Volatility of capital flows and financial liberalization: Do specific flows respond differently? International Review of Economics & Finance, 18, 488–501.

Nocke, V., & Yeaple, S. (2008). An assignment theory of foreign direct investment. The Review of Economic Studies, 75, 529–557.

Noorbakhsh, F., Paloni, A., & Youssef, A. (2001). Human capital and FDI inflows to developing countries: New empirical evidence. World Development, 29(9), 1593–1610.

Qiu, L. D., & Wang, S. (2011). FDI policy, greenfield investment and cross-border mergers. Review of International Economics, 19(5), 836–851.

Razin, A., & Sadka, E. (2006). Foreign direct investment: Analysis of aggregate flows. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Reinhart, C. M., & Reinhart, V. R. (2009). Capital flow bonanzas: An encompassing view of the past and the present. In NBER macroeconomics annual. Chicago University Press, Chicago, IL.

Rothenberg, A. D., & Warnock, F. E. (2011). Sudden flight and true sudden stops. Review of International Economics, 19(3), 509–524.

Salomon, B., & Ruiz, I. (2012). Political risk, macroeconomic uncertainty and the patterns of foreign direct investment. International Trade Journal, 26, 181–191.

Schneider, F., & Frey, B. (1985). Economic and political determinants of foreign direct investment. World Development, 13(12), 161–175.

Sula, O. (2010). Surges and sudden stops of capital flows to emerging markets. Open Economies Review, 21(4), 589–605.

UNCTAD. (2011). World Investment Report: 2011. New York: United Nations Press.

UNCTAD. (2012). World investment report: 2012. New York: United Nations Press.

Wang, M., & Wong, M. C. S. (2009). What drives economic growth? The case of cross-border M&A and greenfield FDI activities. Kyklos, 62(2), 316–330.

Wes, M., & Lankes, H. P. (2001). FDI in economies in transition: M&As versus greenfield investment. Transnational Corporations, 10(3), 113–129.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Burger, M.J., Ianchovichina, E.I. Surges and stops in greenfield and M&A FDI flows to developing countries: analysis by mode of entry. Rev World Econ 153, 411–432 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-017-0276-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-017-0276-2

Keywords

- Foreign direct investment (FDI)

- Greenfield (GF) investment

- Mergers and acquisitions (M&A)

- Capital flows

- Surges

- Stops