Abstract

How do hard economic times affect countries’ foreign policy and, specifically, their international commitments? Although a large body of literature assumes that economic crises lead to the prioritization of domestic politics at the expense of international cooperation, these claims are rarely subjected to systematic empirical tests. This study examines one important aspect of these relationships: the consequences of economic crises for the survival of international organizations (IOs), a question that attracted only scant scholarly attention to date. Theoretically, we argue that even though economic crises can weaken member states’ commitment to IOs, they also underscore their ability to tackle the root causes of such crises and mitigate their most pernicious effects. As such, economic crises are actually conducive to IO longevity. We expect this effect to be especially pronounced for currency crises, IOs with an economic mandate, and regional IOs, given their particular relevance for international cooperation during hard economic times. These conjectures are tested with a comprehensive sample of IOs and data on currency, banking and sovereign debt crises from 1970 to 2014. Using event history models and controlling for several alternative explanations of IO survival, we find ample empirical support for the theoretical expectations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Starting in 1982, a severe economic crisis swept through much of Latin America, leading to this continent’s so-called ‘lost decade.’ Among the casualties of this crisis were regional international organizations (IOs) such as the Central American Common Market (CACM) and the Andean Common Market (ANCOM), which were mothballed as their members embraced protectionist and nationalist economic policies (Mace, 1988). Fifteen years later, it was East Asia’s unfortunate turn. In 1997, Thailand was hit with a devastating banking and currency crisis, which swiftly spread to other members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). This convinced some observers that the days of this regional IO were numbered (Jones and Smith 2002).

At the global level, the Great Depression was associated with the termination of a large number of IOs in the 1930s (Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, 2021). Turning to more recent events, the presumed demise of the so-called liberal international order (LIO) and the IOs associated with it are commonly linked to regional and global economic crises. The decision of the United Kingdom to leave the European Union (EU), famously known as ‘Brexit,’ the Trump administration’s decision to leave the Trans-Pacific Partnership, and its threat to withdraw from the World Health Organization (WHO) and other global IOs, and the persistent impasse in the World Trade Organization (WTO) are, perhaps, the most notable examples of this phenomenon. These salient events underscore the impression that economic hard times are detrimental to international cooperation.

This sentiment is prevalent not only in public discourse, but also in current scholarly research on this topic. In particular, the rise of populist and nationalistic tendencies around the world is attributed to hard economic timesFootnote 1 experienced by large swaths of local societies since the late 2000s (Walter, 2021). These tendencies, in turn, are argued to be accompanied by strong anti-globalization sentiments and a backlash against IOs and other international institutions (Bearce & Jolliff Scott, 2019; Voeten 2021). For example, Copelovitch and Pevehouse (2019, 170; italics ours) go as far as to argue that “In Europe, Brexit, the refugee crisis, and the lingering effects of the Eurozone financial crisis threaten to fracture the European Union, to trigger the breakup of the United Kingdom, and to re-divide Europe along new economic and geopolitical lines.” More generally, Carnegie et al. (2024, 1) point out that “Populists are characterized by their anti-elite, pro-state sovereignty stances, which cause many such leaders to retreat from IOs.” In their turn, Schlipphak et al. (2022) highlight the possibility that governments will use IOs as scapegoats during crises, thereby undermining their legitimacy. All these arguments bode ill for IO survival in the aftermath of economic crises.

Notwithstanding these widespread perceptions, the CACM and ANCOM continued to exist only to be injected with a new lease on life in the early 1990s. The expected demise of ASEAN, too, turned out to be premature and exaggerated. As Ravenhill (2008, 470) argues, “ASEAN not only survived the crisis but, to the surprise of many commentators, appeared to emerge somewhat strengthened by it.” Among other things, the members of ASEAN devised a regional financial mechanism to insulate themselves from future crises (Henning, 2011). And, the 2008 global financial crisis triggered an expansion of resources, authority, and membership of such IOs as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank (WB), the WTO and the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) (Drezner, 2014). With respect to the alleged public backlash against IOs, De Vries et al. (2021) and Schlipphak et al. (2022) point out that their politicization can sometimes lead to greater public support of their existence and activities.

These various episodes and arguments illustrate that economic crises could potentially have either negative or positive effects on the resilience of IOs and, in particular, on their survival.Footnote 2 Surprisingly, studies on this nexus are few and far between, and systematic analyses of these relationships are sorely lacking. In this article, we therefore seek to unpack the implications of economic downturns on the prospect of IO survival. In doing so, we do not deny that economic crises can, indeed, constrain resources and hinder support for cooperation through IOs, at least in the short term. They rarely bring about their demise, we argue. Moreover, economic hard times underscore the ability of IOs to tackle the root causes of crises and to mitigate their most pernicious effects. Consequently, they are deemed more valuable by their member states, who are willing to invest in their preservation. Thus, we argue that not only economic crises do not result in the dissolution of IOs, but also that they prolong their lifespan in important ways.

The positive impact of economic crises on IO longevity is by no means sweeping, however. Contemplating the scope conditions of our core argument, we further conjecture that the strength of this survival-enhancing effect varies across types of IOs and economic crises. With respect to the former, we expect those IOs with an economic mandate to be especially valued, and thus enjoy the support of crisis-ridden member states, compared to IOs that tackle other issue-areas. Regarding the latter, we expect currency crises to have greater cross-border repercussions, compared to banking and sovereign debt crises, due to their greater potential for cross-border contagion. This, in turn, will result in greater need for a coordinated international response.

These theoretical expectations are tested with a comprehensive sample of IOs and data on three types of economic crises from 1970 to 2014. Using event history models and controlling for several alternative explanations of IO survival, we find that, indeed, economic crises tend to increase the survival of IOs. In line with our theoretical expectations, this effect is especially pronounced for currency crises and for IOs with an economic mandate. Null results with respect to IOs with narrow, non-economic, policy competencies further corroborate the logic of our theoretical argument. Beyond these particular relationships, the empirical analysis also tests the effect of other, previously theorized, factors on IO survival in the context of a large, time-varying, sample of IOs. It corroborates some, but not all, earlier findings, as well as increases our confidence in the statistical results.

This article makes several contributions. First, it advances our understanding of the relationships between difficult economic times and international institutional cooperation. Thus far, systematic research of these two phenomena was conducted largely in isolation. Studies that consider the sources and implications of economic crises focused on their domestic economic and, to a lesser extent, political repercussions (Gourevitch, 1986; Pepinsky, 2009). While the life cycle of IOs, and the sources of their demise in particular, are gaining much scholarly interest of late (von Borzyskowski & Vabulas, 2019, 2024a, b; Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, 2020, 2021; Gray, 2018, 2020), recent studies largely overlook the consequences of economic crises (for partial exceptions, see Debre & Dijkstra, 2021a, b; Haftel et al., 2020). By theoretically contemplating the relationships between these two phenomena, this study offers new insights to both research agendas. The empirical analysis brings together for the first time, to the best of our knowledge, comprehensive data on both economic crises and IO survival.

From a more practical standpoint, insofar as IOs restrain “beggar-thy-neighbor” policies during difficult times (Baccini & Kim, 2012; Davis & Pelc, 2017), it is imperative to understand the determinants of their survivability. More generally, given that many countries suffer from economic hard times periodically, identifying the conditions under which international cooperation is more likely to be sustained can assist policy-makers in member states, IO staff, and other stakeholders to better prepare for such ‘rainy days’ and respond to them more quickly and effectively. The role of IO bureaucrats may be especially important in the near future, as a populist backlash against IOs is on the rise in many parts of the globe. For example, Debre and Dijkstra (2021b) show that better staffed IOs were more successful in capitalizing on the COVID-19 health and economic crisis, by expanding their resources and activities. From this perspective, economic crises, even if painful, present opportunities for more robust international cooperation.

This article proceeds as follows. The next section provides a succinct overview of relevant literature. The third section elaborates on our theoretical argument and formulates several hypotheses. The fourth section discusses research design, variables, and data. The fifth section reports and discusses the results of the statistical analysis. The final section concludes.

2 Literature review

Broadly speaking, there are two types of explanations for the survival, or lack thereof, of IOs and other public organizations: internal and external. The former refers to aspects of the organization itself, which may include such factors as its age, size, purpose, independence, and effectiveness (Levine, 1978; Adam et al., 2007; Gray, 2018; Debre & Dijkstra, 2021a, b). The latter refers to characteristics of and relationships between member states as well as environmental pressures that may emanate from competition with other organizations or from political and economic shocks (Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, 2020, 2021). Economic crises commonly reflect an external shock and thus belong in this latter category. Recent research on the life cycle of IOs pays inadequate attention to this factor, however.

In two studies, Eilstrup-Sangiovanni (2020, 2021) shows that more than a third of IOs formed in the last two centuries have actually died. Her analysis considers several important explanations for IO death, but overlooks the potential impact of external economic shocks in member states. In her turn, Gray (2018, 2020) explains variation in the ‘vitality’ of REOs. Distinguishing between living, dead, and zombie IOs (which refers to IOs that formally exist but barely function), she argues that the quality and autonomy of the REO’s bureaucracy best explain their vitality. In her statistical analysis, Gray controls for several alternative explanations, but economic crises is not one of them.

Debre and Dijkstra (2021a) offer the first statistical analysis of IO death that includes time-varying factors and conclude that large secretariats decrease such risk, and thus increase their survival. While their main focus is on factors internal to IOs, they also take into account variation in economic conditions across member states, measured with the change in the average income per capita. This is a step in the right direction, but it is an indirect and imperfect measure of economic crises. Economic decline (or growth) can be incremental and does not always reflect the more dramatic shock that comes with severe economic crises. In addition, this study covers only one-hundred and fifty IOs, which is less than 30% of IOs established since the late 19th century.

Finally, von Borzyskowski and Vabulas (2019, 2024b), contemplate the reasons states withdraw from IOs. Their pioneering work underscores geopolitical and domestic political factors, but overlooks the potential role of economic hardship on member states’ decisions to leave IOs (or not). In a recent article, von Borzyskowski and Vabulas (2024a) do examine the effect of IO withdrawal on IO death, and conclude that some types of withdrawal lead to this outcome, but others do not. These results are based on an analysis of close to five-hundred IOs, but it overlooks the potential impact of economic crises. Our study builds on and contributes to this growing body of research by, first, theoretically contemplating the impact of economic crises on IO longevity, and, second, testing these relationships on a comprehensive sample of IOs and controlling for a battery of alternative explanations.

Voluminous academic research examines the economic and political consequences of economic crises. Nevertheless, the attention paid to the implications of such crises to international institutions, and IOs in particular, is more circumscribed. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, it concentrates on REOs and economic integration, and in particular on the European Union (EU) (Henning, 2011). For example, Mattli (1999) argues that economic crises offer a window of opportunity to advance regional integration and Jones et al. (2016) and Schimmelfennig (2018) claim that economic difficulties facilitated deeper integration in the EU, at least in the long-term.

Other studies offer contrasting perspectives and claim that hard economic times tend to reduce the appetite for further economic cooperation through IOs (Belot & Guinaudeau, 2016; Gómez-Mera, 2009) or that economic crises hinder the institutionalization of REOs in the short-run, but enhance it in the long-run (Haftel et al., 2020). None of these studies entertain the possibility that economic crises will result in either REOs’ increased longevity or, on the other hand, untimely death. This study takes these possibilities seriously, theoretically and empirically, and ponders the implications of this debate for IOs with a variety of policy competencies, not just economic ones.

3 Theoretical framework

We begin with the premise that economic crises, while certainly damaging to the countries they hit, introduce both constraints on and opportunities for IOs. The constraining effect is derived from the observation that operating IOs is costly and depends, for the most part, on financial contributions from member states. The availability of such resources is by no means assured in an institutionally thick global environment (Alter & Raustiala, 2018; Hofmann, 2013). Insofar as difficult economic times dwindle the resources available to member states, they may be expected to reduce their contributions to IOs, or fail to make them altogether. Von Borzyskowski and Vabulas (2019, 2024a) show, for example, that cost considerations are one of the most common justifications states provide for leaving IOs, and that this may lead to IO death. This tendency is not unique to IOs and was observed with respect to domestic organizations as well (Adam et al., 2007).

To the extent that the salience of costs is higher when economic crises hit, one might expect member states to be more reluctant to shoulder them during such times. Furthermore, budgetary shortfalls during hard economic times might make it difficult for an IO to maintain and attract competent staff, who are the lifeblood of a vital organization (Gray, 2018). Economic crises may also undermine the survival of IOs indirectly, through their association with leadership turnover (Chwieroth & Walter, 2017). The notion that political turnover increases the risk of organizational termination is well-recognized in public policy research (Lewis, 2002; Adam et al., 2007; Hofmann, 2013). As Debre and Dijkstra (2021a) note, this logic can be extended to IOs. This seems especially likely if the pendulum swings from internationalist to nationalistic or populist governments (Gray & Kucik, 2017).

All that being said, there are good reasons to be skeptical of this supposed pernicious effect of economic crises on IO longevity. First, even if some member states reduce their contributions, IOs can continue operating, despite having to cut expenses and downscale their activities in the short term, possibly to become more energized when budgetary pressures subside (Haftel et al., 2020). As already mentioned, in the mid-1980s the CACM suffered from severe budget cuts due to the economic crises its member states experienced (Bulmer-Thomas, 1998, 316). Nevertheless, this REO (and its Latin American peers, such as ANCOM) continued to exist, benefitting from greater authority and amassing new policy competencies in the early 1990s. Similarly, in the aftermath of the late-1990s economic crisis, the members of Mercosur adopted various protectionist measures, but roundly rejected the idea of dissolving this REO (Doctor, 2013). Even if member states withdraw from IOs altogether, such action leads to IO death only rarely (von Borzyskowski & Vabulas, 2024a). In addition, some IOs can make ends meet with limited resources, either because they do not have ambitious goals or because they are ‘zombies’ in the first place (Gray, 2020).

The counter-argument is grounded, first, in the notion that the impact of economic crises tends to cross national borders and is therefore not only a domestic but also an international problem. From this perspective, economic hard times may provide incentives for international cooperation, not least through IOs. Such bodies may facilitate coordination efforts between member states to stem the crisis, offer support to those countries that are in dire straits, and devise strategies for renewed growth and employment. Thus, economic crises help clarify the value of IOs for member states and increase their support in and commitment for their continued operation (Schlipphak et al., 2022). To the extent that IOs are instrumental in mitigating the negative effects of the crises, their member states will come to appreciate them and expect their services in the future, and therefore will be keen to ensure their survival. Beyond member states, IO staff is likely to leverage the crisis to prove its worthiness to member states and other stakeholders and make an effort to convince them of the need to prolong its existence and operations.Footnote 3 Here, the IO bureaucracy and like-minded member states can join forces to ensure the former’s survival (Dijkstra & Debre, 2022; Haftel & Hofmann, 2017).

A notable case in point is the International Monetary Fund (IMF), whose main purpose is to assist countries that experience economic crises. In the mid-2000s, in an environment of cheap and abundant global capital and falling demand from middle-income countries for its loans, it appeared as if this IO was ‘slipping into obscurity.’ This led some IMF critics to go as far as to call for its termination (Helleiner & Momani, 2007, p. 11; Meltzer, 2011). Things have changed dramatically when the 2008 economic crisis hit many parts of the world. As various developing and developed countries faced an acute credit crunch and required bail-outs, many turned to the IMF for help. Not only member states supported the existence of this IO, they also decided to dramatically increase their financial contributions to it and to expand its activities. Meltzer (2011) points out, for example, that, as a result of the crisis, it was apparent that “the IMF is back.”

Multilateral development banks (MDBs) are also instrumental in stemming the negative repercussions of economic crises and assisting member states in returning to a path of economic growth and prosperity in their aftermath. Thus, for example, both the WB and the Asian Investment Infrastructure Bank (AIIB) expanded their resources and activities as a result of the COVID-19 global pandemic. With respect to both IOs, member states were quick to turn to and appreciated the technical and financial assistance they offered. Both IOs used this opportunity to expand their activities and engaged in public health policies, a move that was propelled by their officials and like-minded member states within them (Zaccaria, 2023; Haftel et al., 2024). This positive effect on survival is particularly notable with respect to the AIIB (and China, its main champion), given its relatively young age and lack of credibility as an effective MDB.

Second, from a domestic perspective, economic hard times may also extend a lifeline to IOs that promote economic integration. Mattli (1999, 51), for example, argues that economic crises are an important condition for the success of regional integration. According to him, difficult economic times will push decision makers to invest in regional institutions – presumably to obtain greater economic efficiency, which in turn increases their chances of political survival – disregarding “entrenched interest groups’ resistance to integration” (see also Haftel et al., 2020; Jones et al., 2016). Along similar lines, Mansfield and Milner (2018) argue that governments are more likely to sign trade agreements during hard economic times as a signal of competency. Applying this logic to IOs, it is reasonable to expect governments to stick with them during times of crises in order to project stability and credibility.

While the mechanisms thus far discussed pertain to economic IOs, they may apply more generally (but more on this below). To the extent that IOs address issue-areas that have impact on or are affected by economic tides and turns indirectly, such as health, immigration, and the environment, this logic should apply as well. As the recent COVID-19 pandemic showed, for example, health crises can result in economic crises, especially in poorer countries. IOs that tackle health matters – foremost among them, the WHO – helped mitigate some of the pernicious effects of the pandemic, proving their worth to member states (Schlipphak et al., 2022). Thus, the WHO engaged, for the first time, in coordinating global supply chain management (Debre & Dijkstra, 2021b).Footnote 4 In addition, many IOs are ‘general purpose,’ (Hooghe et al., 2019), and many of those have policy competency with respect to economic matters. This is true for many regional IOs, such as ASEAN, the African Union, and the EU, as well as global IOs, such as the United Nations. To the extent that an IO is deemed valuable for its economic mandate, the prospects of its survival are enhanced. Thus, our first hypothesis is:

H1

the probability of survival of IOs is expected to increase as a result of economic crises in their member states.

Thus far, we contemplated ‘average’ effects of economic crises on the prospects of IO survival. Nevertheless, not all IOs are likely to experience the same repercussions as a result of such crises. Presumably, some will weather the economic storm better than others, and some may even thrive under such circumstances. We contemplate the impact of two factors that may condition the relationships between economic crises and IO longevity, one pertains to the mandate of the IO, and another to the type of economic crisis.

First, the discussion thus far suggests that the issue-area(s) in which IOs operate and the problems they are intended to tackle are likely to make a difference. It is perhaps no coincidence that the IOs mentioned in the discussion leading to H1 are economic IOs. Considering that an economic crisis is, by definition, an economic problem, it is reasonable to expect that the services of organizations designed to prevent or mitigate the negative impact of such a crisis, such as the IMF, MDBs, and REOs, will be in high demand when and where they hit. In other words, those IOs that advance economic cooperation (perhaps as one among several issue-areas) are well-equipped to address the issue at hand directly.

In addition, economic IOs can help crisis-hit countries by improving their credit worthiness. Gray (2013) argues and shows that states that foreign investors perceive as risky can associate themselves with more credible countries through REO membership and in so doing attract much-needed capital. While Gray’s framework does not focus on economic crises, her argument is germane to such a situation. Capital flight is one of the hallmarks of economic crises and it tends to spread quickly (see next). Even if REOs are unlikely to avert this process, in the longer run they can help member states display a unified front that will enhance their perceived collective financial responsibility, particularly if some member states are deemed credit-worthy. This appears to be the case for ASEAN in the aftermath of the 1997 economic crisis and the EU in the aftermath of the 2008 economic crisis, for example. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H2

the probability of survival of IOs that have an economic mandate is expected to increase as a result of economic crises in their member states.

One upshot of this hypothesis is that IOs that do not have an economic mandate or tackle issue-areas that have no bearing on the repercussions of economic crises are less likely to benefit from a ‘demand dividend’ in terms of their longevity. For example, it is difficult to see why and how task-specific security, technical, or scientific IOs would gain from economic crises. We therefore expect no effect of economic crises on the survival of these subsets of IOs. The empirical test of this expectation is useful insofar as it serves as a ‘placebo test’ of sorts, against which we assess the main theoretical argument. That is, to the extent that the same kinds of processes generally drive counties to join IOs with various mandates, but some of them are more prone to economic crises than others, false positives are more likely to appear in the analysis of the full sample of IOs, but less so in the sub-sample of economic ones (Chaudoin et al., 2018).

Turning to types of economic crises, and less straightforward, there are good reasons to believe that currency crises will generate greater need for a coordinated international response, relative to sovereign debt and, to a lesser extent, banking crises. That is because currency crises are especially prone to international contagion. Various studies have documented this tendency and attributed it to two main dynamics. The first emphasizes similarity in macroeconomic conditions, which leads economic actors to expect a currency crisis in countries with similar profiles, which in turn leads to speculative attacks and a crisis (Eichengreen et al., 1996). Another, which appears to gain greater empirical support, underscores trade relations (Corsetti et al., 2000; Eichengreen et al., 1996; Haidar, 2012). A currency crisis leads to a sharp devaluation of a country’s currency, which improves its terms of trade vis-à-vis its trading partners, thereby generating pressure on the latter’s balance of payment and currency. Economic actors who observe this process may worry about the collapse of the currency, increase their pressure on it, and push it over the edge. Along these lines, Glick and Rose (1999) show that currency crises tend to cluster geographically and are often regional in nature, attributing this pattern to trade relations.

Given the risk of contagion, global and, even more so, regional IOs are well-placed to tackle currency crises and circumscribe their spillover. Regional IOs, many of which regulate trade policies, can help member states adjust their policies and prevent its spread. As Haidar (2012, 151–152) points out, for example, an important rationale for the rescue package the EU, European Central Bank (ECB), and IMF provided to Greece in 2010-11 was a fear of spillover to other Eurozone countries, a run on the Euro, and even a global economic shock. In another example, the 1997 Asian economic crisis led the members of ASEAN to form the Chiang Mai Initiative, with the broad objectives of advancing financial cooperation, policy dialogue, and monitoring of capital flows (Henning, 2011, 18). Among global IOs, the IMF is particularly notable in this context. As Stanley Fischer (1998), the then First Deputy Managing Director of the IMF, explained this IO’s response to the Asian economic crisis:Footnote 5

From the viewpoint of the international system, the devaluations in Asia will lead to large current account surpluses in those countries, damaging the competitive positions of other countries and requiring them to run current account deficits. Although not by the intention of the authorities in the crisis countries, these are excessive competitive devaluations, not good for the system, not good for other countries, indeed a way of spreading the crisis – precisely the type of devaluation the IMF has the obligation to seek to prevent.

Banking crises, reflecting the insolvency of the baking system, face a lower risk of international contagion. They are most likely to occur when financial institutions in another country hold assets of financial institutions in the crisis-hit country (Pedro, Ramalho, and da Silva 2018), thereby requiring direct financial links between the two countries. Such interconnectedness was less prevalent than trade relations in most parts of the world during most of the time period under investigation.Footnote 6 Finally, a sovereign debt crisis, which occurs when a national government is unable to pay its foreign debt (Breuer, 2004, 296) is also less likely to be contagious. Research indicates that such crises are often driven by macroeconomic fundamentals rather than external sources (Manasse et al., 2003).Footnote 7 IOs can still be instrumental in orchestrating a coordinated response to sovereign debt crises, as the IMF has done rather frequently since the 1980s and as the IMF, EU, and ECB have done with respect to Greece from 2012 onwards, but it appears that currency crises are especially likely to prompt action from and establish the merits of a broader set of regional and global IOs. Our final hypothesis is therefore:

H3

the probability of survival of IOs is expected to increase as a result of currency crises in their member states.

4 Research design

This section begins with the description of the data and the dependent variable. It then turns to the main independent and to several control variables. This study strives to uncover the sources of IO survival, or lack thereof; thus, the unit of analysis is the IO-year and all variables are measured at the IO level. Summary statistics and bivariate correlations of all variables are reported in the Online Appendix. This section concludes with a discussion of the estimation technique – the Cox Proportional Hazards model.

4.1 Sample and data

Similar to other recent studies on IO survival, we use the Correlates of War (COW) International Governmental Organizations Version 3.0 (Pevehouse et al., 2019), the most comprehensive sample of formal IOs currently available, to test the hypotheses presented in the previous section. We therefore adopt its definition of an IO, which includes the following three criteria: (1) it should consist of at least three members of the COW-defined state system; (2) it must hold regular plenary sessions at least once every ten years; (3) and it must possess a permanent secretariat and corresponding headquarters. The COW data include 532 IOs from 1816 to 2014. Given data availability for the variables pertaining to economic crises, we restrict our analysis to the 1970–2014 time period. This leaves us with a somewhat smaller sample of 448 IOs.

4.2 Dependent variable – IO death

IO Death is a binary variable, coded one for death and zero for survival. Its definition and coding are based on von Borzyskowski and Vabulas (2024a). As they explain: “IOs die when they cease operations. In line with the COW criteria above, this happens when IO membership drops below three states or when IOs do not hold a plenary meeting in ten consecutive years or dissolve their secretariat/headquarters” (von Borzyskowski & Vabulas, 2024a, 16–17). The occurrence of IO death in the sample is not uncommon: seventy-three out of 448 (about 16%) IOs died in the forty-four years covered in the main empirical analysis.Footnote 8 Table OA7 in the Online Appendix lists these IOs and their year of death.

This definition of IO death excludes IOs that were replaced by or integrated into another IO (also see, Debre & Dijkstra, 2021a; Dijkstra & Debre, 2022; Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, 2020, 2021). We exclude such instances because the theoretical expectations with respect to the impact of economic crises on their probability are not entirely clear. On the one hand, replacement by or integration into another IO signify, indeed, the dissolution of existing IOs. On the other hand, they might also reflect their upgrade or improvement. Examples of this reality include the replacement of the GATT by the WTO in 1995 and the integration of the West African Monetary Union into the Western African Economic and Monetary Union in 1994. Indeed, the latter case, as well as the replacement of the Union douanière et économique de l’Afrique Centrale by the Communauté économique et monétaire de l’Afrique Centrale were triggered by severe currency crises in most members of these two IOs in 1994. In both instances, the new IOs reflected deeper levels of cooperation and integration (Zafar & Kubota, 2003). The latter possibility is consistent with our theoretical expectations but should lead to the opposite outcome – death rather than survival.

We nevertheless examine the effect of economic crises on all types of IO death as well as on integration and replacement. As reported in Table OA1 in the Online Appendix, including all three types of death in the dependent variable diminishes, but does not erase, the statistical and substantive effect of economic crises. This result is consistent with the notion that such crises induce IOs’ institutional change, rather than death. Economic crises do not seem to affect either IO integration or replacement when analyzed separately or jointly (models 2–4 in Table OA1). One should interpret these results with caution, however, as the number of replaced and integrated IOs in our sample is very small (twenty-eight and fourteen, respectively, compared to seventy-three dead IOs).

4.3 Independent variables – economic crises

The primary independent variables capture the severity of economic difficulties experienced by an IO’s member states. We begin with coding whether an individual member of the organization suffered from a currency, a banking or a sovereign debt crisis in a given year, based on Laeven and Valencia (2020), who provide the most systematic and reliable data currently available. In brief, according to them, a currency crisis is defined as a sharp depreciation of the local currency against the US dollar. A banking crisis is defined by significant signs of financial distress in the banking system and significant banking policy intervention measures in response to significant losses in the banking system. A sovereign debt crisis is defined as a sovereign default to private creditors and/or restructuring.Footnote 9

With these definitions, Laeven and Valencia (2020) identify 239 currency crises, 151 banking crises, and seventy-nine sovereign debt crises from 1970 to 2017. In fifty-four and eleven episodes, respectively, two and three types of economic crises hit a country in the very same year. For example, Nicaragua faced a twin currency and banking crisis in 1990, and so did Bulgaria in 1996. Mexico experienced a twin banking and sovereign debt crisis in 1982 (and a currency crisis in the previous year), and Russia and Uruguay suffered a triple crisis in 1998 and 2002, respectively.Footnote 10

The main independent variable, labeled Economic Crises, is the total number of all types of crises of all states that are members of a given IO. A count of all types of economic crises takes into account the severity and scope of the economic hard times a country faces and the reality that they can be interdependent (for a similar approach, see Davis & Pelc 2015). Counting all member states hit by crises is based on the assumption that as more countries experience such episodes, the effect on IO survival will be more pronounced. Thus, for example, the members of Mercosur suffered from a total of two economic crises in 1994 but as many as five in 2002. It seems reasonable to expect that the imprint of the latter on this IO will be starker than the former.

Economic Crises varies from zero to thirty-nine. As Figure OA1, a histogram of this variable, shows, about half of the sample scores zero on this variable, which is not surprising given that economic crises are not very common. In about thirty-percent of IO-years the value on this variable is one or two, and in about ten-percent of IO-years the value is six or higher. As one might expect, most of the observations that score the highest values on this variable are in years during which economic crises were especially widespread across the globe, e.g., 1982-83, 1992-94, and 2008. Many of these IOs have global membership, but others are regional, e.g., Latin American IOs in the 1980s and African IOs in the 1990s. Given the rather skewed distribution on Economic Crises, outliers might pose a risk to valid inference. To alleviate this concern, we run the basic model with bootstrapping (one-thousand iterations), which is a widely accepted and used method to handle this risk. As Model 1 in Table OA3 shows, the effect of economic crises on IO survival remains intact. The results remain unchanged for the separate types of economic crises as well, reported in Table OA5 in the Online Appendix.

To reduce the risk that the results of the analysis are driven by the construction of Economic Crises, we operationalize this variable in two alternative manners. First, member states score one if they are hit by at least one economic crisis, and zero otherwise. Thus, instances of twin and triple crises are counted as one crisis. Second, we divide the number of crises by the logged number of member states. This measurement is sensitive to the possibility that the share of member states that suffer from economic crises, rather than their absolute number, matters. Models including these variables, reported in Table OA2 in the Online Appendix, further substantiate our main conclusions.

To assess the separate effect of different types of economic crises (H3), we repeat the process described above for currency, banking, and sovereign debt crises. To evaluate the hypothesis that economic crises have varying impact on IOs that address different issue-areas (H2), we split the sample according to the IOs’ mandate (see below). Finally, we consider the possibility that the effect of economic crises on regional and global IOs is different by splitting the sample along those lines.

4.4 Control variables

To ensure that our results are robust to the inclusion of confounding factors, we take into account variables underscored by recent theoretical and empirical studies that examine IO survival or those that make strong theoretical sense, but were not tested rigorously in this context to date.Footnote 11 Similar to economic crises, some of these variables pertain to member states’ characteristics or relationships, such as power asymmetry and heterogeneity. Other variables account for the IOs’ internal attributes, such as institutional design and policy competency. Controlling for both internal and external factors facilitates an informative comparison to and a useful assessment of results reported in previous studies of IO survival.

Power asymmetry – the distribution of power within an IO, and the presence of a hegemon in particular, is mentioned as a condition for the initiation of and successful institutional cooperation. Mattli (1999), for example, argues that a regional hegemon is necessary to advance deep integration, and points to the pivotal roles of Germany in the EU, the US in NAFTA, and Brazil in Mercosur. Others have highlighted the key position of the US within global IOs, such as the UN, the WTO, and the IMF, which allowed it to advance its interests, on the one hand, and demonstrate its benign intentions towards the rest of the member states, on the other (von Borzyskowski & Vabulas, 2024b; Thompson, 2006). From this perspective, both the more and less powerful members have a stake in preserving an IO in which power relations are skewed. This may be especially true during times of crises and uncertainty, when collective goods are likely to be underprovided (Matthijs, 2022, 6–7). We therefore expect greater power asymmetry to be associated with IO longevity. Being the first to assess the impact of this factor on IO survival, we account for it with a measure of power concentration, based on the size of the economy measured with gross domestic product (GDP), within the organization. This variable, labeled Concentration, is bounded between zero and one and decreases as symmetry increases (Haftel, 2013). We employ GDP data from the Penn World Table (PWT) to calculate this variable (Feenstra et al., 2015).

Membership heterogeneity – the divergence of member states’ perspectives is thought to generate tensions and institutional gridlock, thereby undermining IOs’ authority and vitality (Gray, 2018; Haftel & Hofmann, 2019; Hofmann, 2013). Moreover, recent studies expect membership heterogeneity to increase the risk of IO death. Thus, Eilstrup-Sangiovanni (2021, 291; Debre and Dijkstra (2021a, 323) suspect that such divergence increases the number of veto points, hampers cooperation efforts, and, ultimately, hastens the demise of IOs. To be sure, member states diverge on a variety of dimensions, and the most relevant ones are not entirely obvious.

Here, we focus on the divergence in regime type, a domestic characteristic that attracted much attention in research on international cooperation and, more specifically, IOs.Footnote 12 Some studies argue that democracies delegate greater authority to IOs, compared to autocracies, because they advance peaceful dispute resolution and cooperation (Pevehouse & Russett, 2006), and that they are more likely to sustain them over the long haul (Debre & Dijkstra, 2021a). At the same time, Debre (2022) shows that IOs composed of mostly autocratic countries are also beneficial to their member states, because they boost the survival of their regime. Considering the different motivations of democracies and autocracies in forming and sustaining IOs, we expect those that bring together countries with different regime types to be particularly susceptible to dysfunction and death. To measure this variable, labeled Heterogeneity Democracy, we employ the standard deviation of the IO members’ value of polyarchy, based on the Variety of Democracies (V-Dem) data set (Coppedge et al., 2011).

Number of members – the size of membership may have crosscutting effects on the survival of IOs. On the one hand, it is likely to increase preference heterogeneity, and thereby to generate discord and disintegration, as just discussed. In contrast, Eilstrup-Sangiovanni (2020, 362) suggests that large membership comes with greater budgetary and human resources and is therefore more likely to sustain an IO over time. A large number of stakeholders who value the IO also increases its ability to adapt to changing circumstances. Recent studies find that, indeed, IOs with more members are more likely to endure (Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, 2020, 2021; von Borzyskowski & Vabulas, 2024a; Dijkstra & Debre, 2022; Debre & Dijkstra, 2021a). We take this factor into account with Number of Members, which is the logged number of IO members in a given year, based on COW data.

IO independence – theory suggests that more independent IOs benefit from greater vitality and longevity. From the perspective of member states, IOs with greater authority are endowed with more ‘general’ assets, which maintain their value as the surrounding environment changes (Wallander 2000; Dijkstra & Debre, 2022; Haftel & Hofmann, 2017). More independent IOs are also expected to implement their mandate more effectively, to be in a better position to defend their turf and to convince member states that their continued existence is worthwhile (Dijkstra & Debre, 2022; Gray, 2018). Empirical analyses on the relationships between IO independence and death, based on partial samples of IOs, are mixed. Gray (2018) finds that bureaucratic autonomy reduces the risk of death, but Debre and Dijkstra (2021a) find no association between IO institutionalization and its survival.Footnote 13

Our analysis weighs in on this matter by, for the first time, examining the role of IO independence against a comprehensive sample of IOs. We measure this variable with data from Reinsberg and Westerwinter (2023), who coded all IOs in the COW sample on four indicators related to their independence: the presence of a secretariat, a dispute settlement mechanism, a monitoring mechanism, and an enforcement mechanism. Thus, IO Independent ranges from zero to four, reflecting low and high levels of institutional independence, respectively. We note that the values for these indicators are based on the initial IO design and are therefore time invariant.Footnote 14

Mandate – Eilstrup-Sangiovanni (2020, 2021) and von Borzyskowski and Vabulas (2024a) indicate that IOs that address different issue-areas – that is, general purpose, economic, security, social welfare, judicial and technical IOs – have divergent prospects of survival over time. In particular, it appears that economic and security IOs are less durable than general purpose IOs as well as technical or social issues. Eilstrup-Sangiovanni (2018, 2020) suggests that IOs with broad mandates are more adaptable than IOs with narrow mandates and that security and economic IOs are more likely to fall victim to political wrangles and power struggles, compared to more technical or social IOs, given the commonly high stakes in these issue-areas. We therefore include dummy variables for economic and security IOs, with the expectation that such mandates will increase the risk of IO death.Footnote 15 The coding is based on Eilstrup-Sangiovanni (2020). As mentioned above, we also split the sample according to IO mandate to assess the effect of economic crises on IOs that address different subject matters. This analysis excludes general purpose and judicial IOs, because there are no instances of death in the sample for IOs with these mandates.Footnote 16

4.5 Estimation technique – survival analysis

We use event history modelling techniques to estimate the effect of the independent variables on the survival of IOs. This type of analysis estimates the ‘risk’ that an event will take place as time elapses. As such, it is especially suitable to account for variation in the timing of events.Footnote 17 Like other recent quantitative studies that examine the sources of IO death (Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, 2020, 2021; Debre & Dijkstra, 2021a; von Borzyskowski & Vabulas, 2024a), we rely on Cox Proportional Hazards models, which can handle both time-varying and time-constant variables, with robust standard errors clustered by IOs.

We tested the proportional hazard assumption, which is required to produce unbiased estimates, with Schoenfeld residuals and found that it is not violated by most variables in most models. In the handful of cases in which this assumption is violated, we follow the conventional practice and interact the ‘offending’ variables with the natural logarithm of time, thereby allowing their effect to vary over the survival spell (Box- Steffensmeier and Zorn 2001). Such instances are denoted with *LN(t) in the tables of results.

5 Results and discussion

Table 1 presents four models estimating the effect of economic crises and several control variables on the timing of IO death.Footnote 18 The effect of the variable that sums up all types of economic crises is reported in Model 1. Models 2–4 replicate the analysis for currency, banking, and sovereign debt crises, respectively. Table 2 replicates Model 1 in Table 1 for IOs with different mandates (economic, security, social, and technical). These tables report the coefficients, rather than hazard ratios, of the independent variables. Their values reflect the probability of the event (in our case, IO death) occurring given its survival up until that point in time. Thus, a positive value indicates a lower probability of IO survival and a negative value indicates its higher probability. To facilitate a comparison of substantive effects, Table 3 reports the probability of IO survival after sixty years of existence for one standard deviation below the mean (or zero if this value is negative) and one standard deviation above the mean of all independent variables.

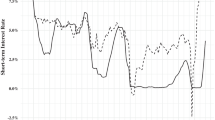

The results provide ample support for the expectation that economic crises will increase the prospects of IO survival. The main independent variable, Economic Crises, is negative and statistically significant at a 99% level of confidence. The substantive impact of this variable is meaningful as well. Figure 1 depicts this effect by plotting the estimated survival rate of IOs when Economic Crises is at zero, its lowest possible value, and one standard deviation above the mean (6.60). It indicates that an IO which its members experience no economic crises has about an 86% chance of survival after sixty years of existence. This value rises to 97%, and thus an increase of about 13%, for an IO whose entire membership experienced six to seven economic crises annually. As Table 3 shows, this is the largest substantive impact among the independent variables included in the model, alongside IO independence and membership.

Consistent with H1, these findings indicate that as the number of economic crises hit member states increases, an IO is more likely to carry on with its operations and possibly even enhance them such that its existence is prolonged. That is, it appears that economic crises enhance the incentives to sustain international cooperation through IOs, possibly to tackle such crises or their broader implications. This does not mean that economic crises do not have a stifling effect on IOs, but rather that, on balance, their invigorating effect is much greater.

To obtain a more nuanced understanding of these results, we first disaggregate economic crises by their different types. As Models 2–4 in Table 1 indicate, in line with H3, not all crises are equally likely to prolong an IO’s lifespan. While all three coefficients keep their negative sign, only Currency Crises is statistically significant, at close to a 99% level of confidence. This variable also has a sizable substantive effect on IO survival, similar to that of the aggregate number of economic crises. On the other hand, Sovereign Debt Crises and, even more so, Banking Crises fall short of conventional levels of statistical significance. It appears, then, that currency crises provide an especially strong motivation to turn to IOs for support and cooperation, thereby increasing their longevity. This expectation is borne out, for example, in the cases of ASEAN and Mercosur, in which member states were hit by currency crises in 1997-8 and 2002, respectively. These experiences have strengthened cooperation efforts through these REOs. As mentioned in the previous section, however, states occasionally suffer from two or three types of crises simultaneously, so such separate analyses should be interpreted with caution.

Turning to IOs with different mandates, in line with the theoretical expectations (H2), the coefficient on Economic Crises is in the expected direction and highly statistically significant for the subset of IOs that address economic matters. The substantive impact of this variable is especially sizable. Figure 2 plots the estimated survival rate of IOs with an economic mandate when Economic Crises is at zero and one standard deviation above the mean, based on Model 1 in Table 2. It shows that those IOs that their members experience no economic crises have about a 70% chance of survival after sixty years of existence, compared to 97% (and thus an increase of about 40%) for economic IOs which its entire membership suffered six to seven crises annually.

Thus, economic crises are especially likely to increase the probability of survival of economic IOs, ostensibly to assist their member states to overcome such crises and perhaps better prepare for future ones. These dynamics appear to be at work in many REOs (Debre & Dijkstra, 2021b; Haftel et al., 2020). They are also likely to be applicable to IOs that provide financial assistance, e.g., MDBs and multilateral lenders such as the IMF. In line with our expectations, IOs with narrow, security, social, and technical mandates, which serve as a placebo test of sorts, fall far short of statistical significance. These non-results provide additional support for the theoretical logic, which emphasizes the value of IOs with economic competencies in tackling economic crises and their repercussions.

A third factor that appears to condition the effect of economic crises on IO survival is geographical scope. As models 3 and 4 in Table OA2 show, Economic Crises is highly statistically and substantively significant with respect to regional IOs, but statistically insignificant in relation to global IOs (but one should keep in mind that only four global IOs included in the analysis have died). This finding is consistent with the reality that economic crises, and currency crises in particular, tend to be regionally contagious and call for a coordinated regional response. On the whole, the analysis provides strong empirical support for the positive impact of economic crises on IO survival. At the same time, it indicates that this effect varies across different types of economic crises and IOs in theoretically predictable manners.

The control variables are mostly statistically significant and in the expected direction, further increasing our confidence in the results of the analysis.Footnote 19 They also offer several valuable insights with respect to the sources of IO survival. Starting with aspects pertaining to the member states, Power Asymmetry, a factor that was not tested in relation to IO death thus far, is negatively signed and highly statistically significant in most models. Its substantive impact is less pronounced than Economic Crises, however. Insofar as higher power asymmetry reflects an IO that is sustained by a global or regional hegemon, this result corroborates the view that such hegemony is conducive to the longevity of IOs.

We find that members’ heterogeneity increases the risk of IO death, but that this effect is modest and uncertain. The variable Heterogeneity Democracy is positively signed and highly statistically significant in all models in Table 1. As reported in Table 3, the substantive effect of this variable is lower than most other variables included in the analysis. This variable is also statistically insignificant in most models in Table 2 as well as when other control variables are excluded (Model 3 in Table OA4). Furthermore, measuring heterogeneity with ideal point estimates, based on voting in the UNGA, is also positive but statistically insignificant (Model 3 in Table OA3). This is broadly consistent with the findings of Debre and Dijkstra (2021a), suggesting that heterogenous membership is not necessarily detrimental to IO survival. The number of IO members has a negative and statistically significant coefficient across most models. The substantive effect of this variable is also quite large and parallels those of Economic Crises and IO independence. These results corroborate previous findings that wide-ranging membership increases the prospects of IO survival (Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, 2020, 2021; von Borzyskowski & Vabulas, 2024a), presumably because it furnishes IOs with resources and increases their ability to adapt under changing circumstances.

With respect to the attributes of IOs themselves, rather than their member states, their degree of independence is highly statistically significant in all models. As already noted, its substantive effect is equivalent to the effect of Economic Crises. As institutional theory expects, more authoritative IOs are more resilient than their less independent counterparts. This result is also consistent with the findings of Gray (2018), who underscores the contribution of independent secretariats to the survival and vitality of their IOs. It is also consistent with Debre and Dijkstra’s (2021a, b) emphasis on powerful IO bureaucracies, even though a measure of IO independence is not statistically significant in their own analysis. The results on IO mandate are largely consistent with previous findings (Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, 2020, 2021; von Borzyskowski & Vabulas, 2024a). Economic and security IOs are more vulnerable to death than IOs that are multipurpose or address social or technical matters. These findings resonate with Eilstrup-Sangiovanni (2020, 2021), who suggests that IOs addressing matters of ‘high-politics’ are more likely to succumb to political power struggles. Nevertheless, the substantive effect of these two variables is smaller than some of the other explanatory variables.

Taking the results on the control variables together, the analysis indicates that the survival of IOs is affected by the characteristics and relationships between member states as well as their institutional features. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, the prospects of cooperation through IOs are determined by both external and internal factors in sometimes complex manners. We have seen, for example, that the effect of economic crises hinges, at least to an extent, on the mandate and geographical scope of the IO. On the whole, though, the effect of economic crises on the survival of IOs is robust to the inclusion of various external and internal factors and model specifications. Moreover, its substantive effect is larger or equivalent to alternative explanations for IO survival, underscoring the need to take economic tides and turns into account when trying to grasp the sources of IOs’ life cycles.

6 Conclusion

This study takes a first stab at the relationships between economic crises and the survival of IOs. It begins by theoretically contemplating the consequences of the former for the latter, and by suggesting that it can have both negative and positive effects on IO longevity. It also underscores the possibility that the impact of economic crises on IO death is contingent on other factors, specifically the mandate of the IO and the type of economic crisis member states experience. Bringing together comprehensive data on IO dissolution and economic crises in their member states, as well as on a host of additional factors, we find that economic crises are conducive to the longevity of IOs. We also find that this effect is especially visible for IOs with an economic mandate and for currency crises.

Our analysis highlights the reality that economic crises are by no means detrimental to international cooperation through IOs. In fact, they bring to light the need to cement such cooperation in order to provide international solutions to cross-border problems. Possibly, even if economic hard times make cooperation more difficult in the short term, they encourage it in the longer term (Haftel et al., 2020). This is notable given the widespread view that the growing challenges to the LIO emanate from recurring economic crises in many countries. The findings reported here join recent studies of IO death that demonstrate that this phenomenon is neither new nor a byproduct of the recent legitimacy crisis of the LIO (Gray, 2018; Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, 2020, 2021; Debre & Dijkstra, 2021a, b; von Borzyskowski & Vabulas, 2024a, b).

This article points to several promising avenues of future research. First, it zeros in on IO death, which is a rather extreme outcome. Further studies might explore the effect of economic crises on IO scope expansion, IO institutionalization, and member states strategies more broadly.Footnote 20 For example, to the extent that the argument made herein is sound, one might expect economic IOs to produce greater output in the aftermath of economic crises (Lundgren et al., 2023). Another question that merits investigation is the relationships between other types of crises and IO survival. One might ask, for example, what are the implications of armed conflicts and war for the duration of IOs with a security mandate or how natural disasters affect those IOs that aspire to manage disaster relief and aid.

Data availability

The replication data, code, and appendix for this article will be made available at the Review of International Organizations’ webpage upon its publication online.

Notes

We use the terms economic ‘crises,’ ‘hard times,’ and ‘downturns’ interchangeably. As discussed in subsequent sections, they refer to instances of a serious negative economic shock, often originated by currency, banking, or sovereign debt crises.

We define survival (as well as longevity, interchangeably) as the continued existence of an IO. As we discuss in subsequent sections, these concepts are defined binarily, such that an IO is either alive or dead in a given year (in an auxiliary analysis, we also consider either replacement of an IO by or an integration of an IO into another IO). Our reason for this approach is twofold. First, the existence of an IO is a precondition for its activities, performance, and the like. Second, unfortunately, data on various aspects of IO strength and institutional design are still not available for a comprehensive sample of IOs. Thus, for example, the Measurement of International Authority (MIA) data set (Hooghe et al., 2019; Haftel & Lenz, 2022), which offers fine-grained measures of IO authority, includes a (non-random) sample of eighty IOs (Debre & Dijkstra (2021b) use the MIA data set as well and analyze seventy-five IOs). Gray (2018), who distinguishes between live and ‘zombie’ IOs, coded seventy-five regional economic organizations (REOs), and Haftel et al. (2020) analyze the institutionalization of thirty REOs. Thus, there is a trade-off between one’s ability to examine the survival of most IOs and to investigae fine-grained institutional aspects of rather limited samples of IOs. In this study, we turn our attention to the former, leaving the latter for future research.

Interestingly, the WHO not only survived but was also able to expand its activities despite the withdrawal of funds from and the initiation of a withdrawal process of its main funder, the US (Debre & Dijkstra, 2021b). This further illustrates the resilience of IOs during hard economic times accompanied by inhospitable geopolitical conditions.

Nevertheless, since the 1990s, with increasing economic globalization, currency and banking crises tend to be intertwined, and are therefore labeled ‘twin crises’ (Breuer, 2004; Laeven & Valencia, 2020). This reality, further discussed in the next section, suggests that analyzing these types of crises separately should be treated with caution. Furthermore, the growing international exposure of financial institutions since the early 2000s has led to the global spread of the 2008 economic crisis (Dungey & Gajurel, 2015). Consistent with our theoretical expectations, this crisis persuaded states to develop a new international regulatory framework for banks, known as ‘Basel III,’ under the auspices of the BIS (Drezner, 2014).

That is not to say that it cannot be intertwined with currency and banking crises. In some circumstances, the latter are an early warning sign of the former, as was the case in Greece in the late 2000s and early 2010s.

The number of IO deaths falls in models that examine subsets of the data, e.g., IOs with a specific mandate. It is reported at the bottom of all tables presenting statistical results.

In a handful of cases, countries defaulted on their debt and went through restructuring in the same year. We count it as a one instance of a sovereign debt crisis.

It is also possible that one type of crisis in a given year will trigger a different type of crisis in the following year. For example, Thailand and Indonesia were hit by a banking crisis in 1997 and a currency crisis in 1998. On the sequencing of economic crises, see Laeven and Valencia (2020, 314).

We tested for several additional, potentially relevant, explanatory factors, that turned out to be statistically insignificant and did not affect the results. These include the average level of democracy, intra-regional trade, and the average level of income per capita. We also examined whether an IO is regional, interregional or global, and the continental location of regional IOs (Africa, the Americas, Asia, and Europe). The results on the control variables remain intact after dropping Economic Crises from the analysis, such that the sample is expanded to the 1950–2014 time period. All these results are on file with Authors.

Gray (2018); Debre and Dijkstra (2021a) emphasize geopolitical differences, which they operationalize as the standard deviation of the members’ ideal point distance, based on United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) voting patterns (Bailey et al., 2017), and obtain mixed results. In a supplementary analysis, reported in Model 3 in Table OA3, we substitute Heterogeneity Democracy with this variable, labeled Heterogeneity Ideal Point. This variable is in the expected direction, but statistically insignificant, and does not affect the results on other variables.

They do find strong positive relations between the size of an IO’s bureaucracy and the survival of IOs. They also find that less institutionalized IOs are more likely to be replaced, rather than die (this result is not supported by the analysis here, see Model 3 in Table OA1).

Unfortunately, data on institutional design of IOs over time is not available for the entire COW sample. Debre and Dijkstra’s (2021a) data on bureaucratic size are also time invariant and cover only 150 IOs. It is therefore not suitable for our purposes here.

The reference categories are general purpose, social welfare, technical, and judicial IOs. We also tested for the scope of the IO (narrow, medium, or broad). This factor was statistically insignificant and did not affect the results.

Several IOs that are coded as general purpose by Eilstrup-Sangiovanni (2018) have an economic mandate at their core. This is especially the case for REOs, such as the EU, ASEAN, the Caribbean Community, and the Southern African Development Community. Coding such IOs as having an economic mandate does not affect the results, on file with Authors, in a meaningful manner.

Box-Steffensmeier et al., 2003.

Table OA4 in the Online Appendix reports the results for the effect of Economic Crises on IO death without control variables and then with each control variable at a time. With the exception of Heterogeneity Democracy, which loses statistical significance, the results remain intact.

Some variables lose statistical significance in the models pertaining to IOs with different mandates and in other sub-samples reported in the Online Appendix. Considering the smaller sample sizes, these results should be interpreted with caution.

References

Adam, C., Bauer, M., Knill, C., & Studinger, P. (2007). The termination of Public Organizations: Theoretical perspectives to revitalize a Promising Research Area. Public Organization Review, 7, 221–236.

Alter, K. J., & Raustiala, K. (2018). The rise of International Regime Complexity. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 14, 329–349.

Baccini, L., & Kim, S. Y. (2012). Preventing protectionism: International Institutions and Trade Policy. The Review of International Organizations, 7(4), 369–398.

Bailey, M. A., Strezhnev, A., & Voeten, E. (2017). Estimating dynamic state preferences from United Nations voting data. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61(2), 430–456.

Bearce, D. H., & Jolliff Scott, B. J. (2019). Popular non-support for international organizations: How extensive and what does this represent? The Review of International Organizations, 14, 187–216.

Belot, C., & Guinaudeau, I. (2016). Economic crisis, crisis of support? How macro-economic performance shapes citizens’ support for the EU (1973–2014). In S. Saurugger, & F. Terpan (Eds.), Crisis and Institutional Change in Regional Integration (pp. 93–112). Routledge.

Box-Steffensmeier, J. M., Reiter, D., & Zorn, C. J. (2003). Nonproportional hazards and event history analysis in international relations. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 47(1), 33–53.

Breuer, J. B. (2004). An exegesis on currency and banking crises. Journal of Economic Surveys, 18(3), 293–320.

Bulmer-Thomas, V. (1998). The Central American Common Market: From closed to open regionalism. World Development, 26(2), 313–322.

Carnegie, A., Clark, R., & Kaya, A. (2024). Private participation: How populists engage with International Organizations. Journal of Politics.

Chaudoin, S., Hays, J., & Hicks, R. (2018). Do we really know the WTO cures cancer? British Journal of Political Science, 48(4), 903–928.

Chwieroth, J. M., & Walter, A. (2017). Banking crises and politics: A Long-Run Perspective. International Affairs, 93(5), 1107–1129.

Copelovitch, M., & Pevehouse, J. C. (2019). International organizations in a new era of populist nationalism. The Review of International Organizations, 14, 169–186.

Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Altman, D., Bernhard, M., Hicken, F. S., Kroenig, A. M., et al. (2011). Conceptualizing and measuring democracy: A New Approach. Perspectives on Politics, 9(2), 247–267.

Corsetti, G., Pesenti, P., Roubini, N., & Tille, C. (2000). Trade and contagions devaluations: A Welfare-based Approach. Journal of International Economics, 51, 217–241.

Davis, C. L., & Pelc, K. J. (2017). Cooperation in Hard Times: Self-Restraint of Trade Protection. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61(2), 398–429.

De Vries, C. E., Hobolt, S. B., & Walter, S. (2021). Politicizing international cooperation: The mass public, political entrepreneurs, and political opportunity structures. International Organization, 75(2), 306–332.

Debre, M. J. (2022). Clubs of autocrats: Regional organizations and authoritarian survival. The Review of International Organizations, 17(3), 485–511.

Debre, M. J., & Dijkstra, H. (2021a). Institutional design for a post-liberal order: Why some international organizations live longer than others. European Journal of International Relations, 27(1), 311–339.

Debre, M. J., & Dijkstra, H. (2021b). COVID-19 and policy responses by international organizations: Crisis of liberal international order or window of opportunity? Global Policy, 12(4), 443–454.

Dijkstra, H., & Debre, M. J. (2022). The death of major international organizations: When institutional stickiness is not enough. Global Studies Quarterly, 2(4), 1–13.

Doctor, M. (2013). Prospects for deepening mercosur integration: Economic asymmetry and institutional deficits. Review of International Political Economy, 20(3), 515–540.

Drezner, D. W. (2014). The system worked: Global economic governance during the great recession. World Politics, 66(1), 123–164.

Dungey, M., & Gajurel, D. (2015). Contagion and banking crisis–international evidence for 2007–2009. Journal of Banking & Finance, 60, 271–283.

Eichengreen, B., Rose, A., & Wyplosz, C. (1996). Contagious currency crises: First tests. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 98(4), 463–484.

Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, M. (2020). Death of International Organizations. The Organizational Ecology of Intergovernmental Organizations, 1815–2015. The Review of International Organizations, 15(2), 339–370.

Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, M. (2021). What kills international organisations? When and why international organisations terminate. European Journal of International Relations, 27(1), 281–310.

Feenstra, R. C., Inklaar, R., & Timmer, M. P. (2015). The Next Generation of the Penn World table. American Economic Review, 105(10), 3150–3182.

Glick, R., & Rose, A. K. (1999). Contagion and trade: Why are currency crises Regional. Journal of International Money and Finance, 18(4), 603–617.

Gómez-Mera, L. (2009). Domestic constraints on Regional Cooperation: Explaining Trade Conflict in MERCOSUR. Review of International Political Economy, 16(5), 746–777.

Gourevitch, P. (1986). Politics in Hard Times: Comparative responses to International Economic crises. Cornell University Press.

Gray, J. (2013). The company states keep: International economic organizations and investor perceptions. Cambridge University Press.

Gray, J. (2014). Domestic capacity and the implementation gap in Regional Trade agreements. Comparative Political Studies, 47(1), 55–84.

Gray, J. (2018). Life, death, or Zombie? The Vitality of International Organizations. International Studies Quarterly, 62(1), 1–13.

Gray, J. (2020). Life, death, inertia, change: The hidden lives of international organizations. Ethics & International Affairs, 34(1), 33–42.

Gray, J., & Kucik, J. (2017). Leadership turnover and the survival of International Trade commitments. Comparative Political Studies, 50(14), 1941–1972.

Haftel, Y. Z. (2013). Commerce and Institutions: Trade, Scope, and the Design of Regional Economic Organizations. The Review of International Organizations, 8(3), 389–414.

Haftel, Y. Z., & Hofmann, S. C. (2017). Institutional Authority and Security Cooperation within Regional Economic Organizations. Journal of Peace Research, 54(4), 484–498.

Haftel, Y. Z., & Hofmann, S. C. (2019). Rivalry and overlap: How Regional Economic organizations Encroach on Security Organizations. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 63(9), 1180–2206.

Haftel, Y. Z., & Lenz, T. (2022). Measuring Institutional Overlap in Global Governance. The Review of International Organizations, 17(2), 323–347.

Haftel, Y. Z., Wajner, D., & Eran, D. (2020). The short and Long(er) of it: The Effect of Hard Times on Regional Institutionalization. International Studies Quarterly, 64(4), 808–820.

Haftel, Y. Z., Hofmann, S. C., & Ella, D. (2024). Hedging for Influence: China’s Engagement Strategies in the World Bank and the AIIB during the COVID-19 Crisis. Jerusalem and Florence: Working Paper.

Haidar, J. I. (2012). Currency Crisis Transmission through International trade. Economic Modelling, 29, 151–157.

Helleiner, E., & Momani, B. (2007). Slipping into Obscurity? Crisis and Reform at the IMF. CIGI Working Paper No. 16. The Centre of International Governance Innovation, Waterloo: University of Waterloo.

Henning, C. R. (2011). Economic Crises and Institutions for Regional Economic Cooperation. Asian Development Bank Working Paper Series on Regional Economic Integration, No.81. Manila: Asian Development Bank.

Hofmann, S. C. (2013). European security in NATO’s shadow: party ideologies and institution building. Cambridge University Press.

Hooghe, L., Lenz, T., & Marks, G. (2019). A theory of international organization. Oxford University Press.

Jones, D. M., & Smith, M. L. (2001). ASEAN’s imitation community. Orbis, 46(1), 93–110.

Jones, E., Kelemen, R. D., & Meunier, S. (2016). Failing Forward? The Euro Crisis and the Incomplete Nature of European Integration. Comparative Political Studies, 49(7), 1010–1034.

Krasner, S. D. (Ed.). (1983). International regimes. Cornell University Press.

Laeven, L., & Valencia, F. (2020). Systemic banking crises database II. IMF Economic Review, 68, 307–361.

Levine, C. H. (1978). Organizational decline and Cutback Management. Public Administration Review, 38, 316–325.

Lewis, D. E. (2002). The politics of Agency termination: Confronting the myth of Agency Immortality. The Journal of Politics, 64(1), 89–107.

Lundgren, M., Squatrito, T., Sommerer, T., & Tallberg, J. (2023). Introducing the intergovernmental policy output dataset (IPOD). The Review of International Organizations, 1–30.

Mace, G. (1988). Regional integration in latin America: Long and winding road. International Journal, 43(3), 404–427.

Manasse, P., Schimmelpfennig, M. A., & Roubini, N. (2003). Predicting sovereign debt crises. International Monetary Fund.

Mansfield, E. D., & Milner, H. V. (2018). The domestic politics of Preferential Trade agreements in Hard Times. World Trade Review, 17(3), 371–403.

Matthijs, M. (2022). Hegemonic leadership is what states make of it: Reading Kindleberger in Washington and Berlin. Review of International Political Economy, 29(2), 371–392.

Mattli, W. (1999). The logic of Regional Integration: Europe and Beyond. Cambridge University Press.

Meltzer, A. (2011). The IMF returns. The Review of International Organizations, 6, 443–452.

Pepinsky, T. B. (2009). Economic crises and the Breakdown of authoritarian regimes: Indonesia and Malaysia in comparative perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Pereira Pedro, C., Ramalho, J. J., & da Silva, J. V. (2018). The main determinants of banking crises in OECD countries. Review of World Economics, 154(1), 203–227.

Pevehouse, J. C., & Russett, B. (2006). Democratic International Governmental Organizations Promote Peace. International Organization, 60(4), 969–1000.

Pevehouse, J., Nordstrom, T., & Warnke, K. (2004). The correlates of War International 2 Governmental Organizations Data Version 2.0. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 21(2), 101–119.

Pevehouse, J., McManos, R., & Nordstrom, T. (2019). Codebook for Correlates of War 3 International Governmental Organizations Data Set Version 3.0. http://www.correlatesofwar.org/data-sets/IGOs/.

Ravenhill, J. (2008). Fighting irrelevance: An economic community ‘with ASEAN characteristics. The Pacific Review, 21(4), 469–488.

Reinsberg, B., & Westerwinter, O. (2023). Institutional overlap in global governance and the design of intergovernmental organizations. The Review of International Organizations, 1–32.