Abstract

Students’ intrinsic motivation to read, which is relevant to all forms of learning, tends to decline throughout secondary school. Based on self-determination theory (SDT), this study examines whether this downward trend is slowed when students perceive greater autonomy support in the classroom. We used large-scale panel data from the NEPS comprising N = 8193 students in Germany who reported their intrinsic motivation to read and their perceived autonomy support from German teachers at annual intervals from fifth to eighth grade. Scalar longitudinal measurement invariance was found for intrinsic reading motivation (IRM) and teacher autonomy support (TAS). A dual change score model showed a decline in IRM and a negative, non-significant decrease in TAS over time. Confirming our hypothesis, the decline in IRM was slowed by earlier levels of TAS. We discuss methods to counteract the decline in intrinsic reading motivation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Intrinsic motivation, understood as doing activities “‘for their own sake,’ or for their inherent interest and enjoyment” (Ryan & Deci, 2020, p. 2; see also Deci & Ryan, 2000), is of critical importance for school achievement and performance (Cerasoli et al., 2014; Kriegbaum et al., 2018; Ratelle et al., 2007; Taylor et al., 2014). Meta-analytical evidence suggests that students’ motivation (i.e., their interest, goal orientation, and self-concept) for different school subjects declines throughout their school career (Scherrer & Preckel, 2019). A decline in intrinsic reading motivation (IRM), which is of particular importance given that reading is required in all domains, seems to be especially pronounced across secondary school (e.g., Miyamoto et al., 2020). According to self-determination theory (SDT), the fulfillment of a student’s needs for belonging, competence, and autonomy enhances or maintains their intrinsic motivation in this context (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2000b). Adolescents’ increasing need for autonomy, which contrasts with the decline in autonomy support across secondary school, has been used to explain students’ decline in reading motivation (e.g., Miyamoto et al., 2020). Although there is empirical evidence confirming that autonomy support is relevant for students’ intrinsic motivation (e.g., Chirkov & Ryan, 2001; Gillet et al., 2012), research has not addressed whether teacher autonomy support can buffer the decline in intrinsic reading motivation. Based on a sample of N = 8193 secondary school students, the present study uses the dual change score model (DCSM) to investigate whether a teaching style that promotes teachers’ autonomy support (TAS) in the school subject German counters the tendency for students’ IRM to decline between fifth and eighth grade.

Intrinsic reading motivation and its development

IRM positively contributes to students’ reading behavior, persistence in reading, and reading competence (Becker et al., 2010; Guthrie et al., 2004; Schiefele et al., 2012). This means that reading is an important prerequisite for students’ participation at school across all subjects, since tasks, learning materials, and exams are to a large extent presented in text-based forms. Becker et al. (2010) found that fourth graders’ IRM positively relates to their reading literacy in sixth grade. This relationship was mediated by the amount students read, indicating that intrinsically motivated students tend to read more frequently and as a result develop better reading skills (Becker et al., 2010). Fostering and maintaining students’ IRM are therefore an important objective that should always be met when promoting reading literacy in school (KMK, 2022).

Consistent with findings showing an overall developmental decline in several motivational constructs throughout students’ educational careers (Gottfried et al., 2001; Scherrer & Preckel, 2019), research on students’ IRM confirms a declining trend (Bouffard et al., 2001; Kolić-Vehovec et al., 2014; McElvany et al., 2008; Miyamoto et al., 2020; Schaffner et al., 2016; van de Gaer et al., 2009; Viljaranta et al., 2014). Although two studies report no substantial decline in IRM (Lau, 2016; Schiefele et al., 2016) and findings are therefore not unanimous, those studies spanned only 1 year and presumably underestimated developmental changes. Miyamoto et al. (2020) found that when studying developmental changes in students’ IRM across a longer period—i.e., from grades five to eight—and ensuring the measurement invariance of the scales used, the decline in IRM seems to be particularly pronounced. Their results also indicate that the developmental decline in IRM is larger in size than the decline in motivation found in other domains (Miyamoto et al., 2020; Scherrer & Preckel, 2019). Given that IRM is closely tied to reading proficiency (Miyamoto et al., 2018, 2020; Schiefele et al., 2012), which is required in all school subjects, it is of particular relevance to identify relevant teaching practices that can counter this trend.

Explaining the developmental decline: teacher autonomy support is crucial

To explain the trend of declining intrinsic motivation, researchers draw on different theoretical approaches. Stage-environment fit theory suggests that declines in intrinsic motivation might result from incongruence between adolescents’ needs and the opportunities afforded to them within their school environments (Eccles et al., 1993). Cognitive evaluation theory, a sub-theory within SDT, postulates that intrinsic motivation may decline if the learning environment does not sufficiently support an individual’s basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Deci & Ryan, 1985, 1987, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2000b). According to these theories, the decline in IRM across secondary school may be due to adolescents gaining greater needs for autonomy and social acceptance, which are often not met in higher grades where less autonomy is given to students regarding their studies (for a similar suggestion see Scherrer & Preckel, 2019). Adding to this, cognitive evaluation theory suggests that autonomy support alone may be sufficient to foster intrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000a). In contrast, competence must be accompanied by autonomy support (Ryan & Deci, 2000a), and relatedness seems to play a less central role in maintaining and enhancing intrinsic motivation (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Thus, autonomy, which describes an individual’s need to feel ownership of their behavior and actions, may be especially crucial (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Wang et al., 2019).

Cognitive evaluation theory suggests that autonomy support from both teachers and parents is beneficial to students’ intrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2020). In the present study, we will focus on teacher autonomy support (TAS) because decreasing autonomy support across secondary school is seen as one of the major reasons for the decline in IRM (e.g., Miyamoto et al., 2020). TAS describes the teacher as a person who listens to the student’s perspective, acknowledges their perception and feelings, and provides them with information and opportunities to make choices with minimal use of pressure, control, and demands (Frederick et al., 2022; Simon & Salanga, 2021; Williams & Deci, 1996). Autonomy-supportive teachers give their students space to unfold their ideas and initiatives before intervening. TAS is characterized by respectful, appreciative, and student-centered behavior by teachers (Reeve et al., 2004; Simon & Salanga, 2021). Students in such an environment feel free to ask questions and are encouraged to participate (Simon & Salanga, 2021; Williams & Deci, 1996). From a theoretical perspective, students who are provided with autonomy in the classroom, e.g., in the school subject German, might perceive activities like reading and examining texts to be self-initiated and congruent with their own values and interests. Thus, autonomy-supportive contexts tend to promote an individual’s identification with external regulations, which is described as a process of internalization that can enhance or maintain intrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2020).

Previous research on the relationship between intrinsic reading motivation and teacher autonomy support

The notion that TAS is crucial for intrinsic motivation has been confirmed for different school levels and various domains (for an overview: e.g., Bureau et al., 2022; Núñez & León, 2015; Ryan & Deci, 2020). A recent meta-analysis by Bureau et al. (2022), which included 144 independent samples and about 80,000 students, suggests that intrinsic motivation is more closely linked to TAS (ρ = 0.48 across k = 47 studies) than to parents’ autonomy support (ρ = 0.23 across k = 12 studies). Although there may be a publication bias and, thus, the actual relationship between intrinsic motivation and TAS may be somewhat smaller, the authors highlight that their results are still accurate. In addition, the relationship between intrinsic motivation and parents’ autonomy support seemed to decrease as students grew older. This was, however, not the case for the relationship between intrinsic motivation and TAS.

Bureau et al. (2022) underlined that studies should move towards implementing longitudinal designs to gain more insights into the causal links involved. Of the 47 studies included in the meta-analysis that examined the relationship between intrinsic motivation and TAS, only three studies had applied a longitudinal design (authors’ count based on supplementary material of Bureau et al., 2022).Footnote 1 Two of these longitudinal studies were conducted in K12 classroom and examined the relationship between intrinsic motivation and TAS in different grade levels and domains (Hagger et al., 2015; Savard, 2013).Footnote 2 Based on data from 220 12- to 15-year-old Pakistani high school students, Hagger et al. (2015) investigated the relationship between TAS and intrinsic motivation in mathematics classrooms over the duration of 6 weeks. Variance-based structural equation modeling showed that students who perceived their mathematics teacher to support their autonomy in school experienced higher levels of intrinsic motivation in their studies. Moreover, higher levels of autonomy support and intrinsic motivation in school were positively related to intrinsic motivation for homework in mathematics. The authors concluded that—in the field of mathematics—autonomy-supportive teaching in the classroom affects intrinsic forms of motivation in school and outside of school. Savard (2013) examined the longitudinal relationship between TAS and intrinsic motivation over the course of 6 months in a clinical sample of N = 115 French-speaking maladjusted teenagers with a mean age of 14.4 years. They had severe emotional and behavioral problems and attended special schools for maladjusted youth in Quebec, Canada. Using structural equation modeling (SEM), Savard (2013) found that improvements in teachers’ provision of autonomy support over the school year were associated with students’ higher need satisfaction, which then led to higher levels of self-determined motivation. However, though these studies are insightful, they did not focus on the domain of reading.

Similar to meta-analytic findings that interventions training teachers to be more supportive of autonomy are effective overall (Su & Reeve, 2011), other studies have examined the benefits of training teachers to implement motivational strategies to foster students’ IRM, but without focusing on TAS. For instance, Wigfield (2005) examined the effectiveness of the Concept Oriented Reading Instruction (CORI) program that implements various motivational strategies, including TAS. Based on a sample of N = 160 third and fourth graders, the study indicates that teachers’ participation in the program positively contributed to the students’ IRM (see also Guthrie et al., 2004).

In a similar vein, to study the promotion of IRM, De Naeghel et al. (2014b) employed an embedded mixed-method design. They selected three teachers, who were excellent in promoting autonomous reading motivation, and their N = 52 students. The results showed that—in the case of these three teachers—SDT’s teaching dimensions of autonomy support, structure, and involvement are valuable strategies for promoting fifth graders’ autonomous reading motivation. However, these studies did not disentangle the effects of different motivational teaching practices and, therefore, did not quantify the role of TAS in the development of IRM.

Taken together, longitudinal studies in the classroom context that focus on the benefits of TAS for the development of students’ IRM are rare. Previous studies are mainly based on small samples and cover short periods ranging between 6 weeks and 6 months. Applying longitudinal study designs spanning several school years is necessary to identify relevant teaching practices that will counter the decline in IRM.

Present study

The present study extends previous research on the longitudinal relationship between intrinsic motivation and TAS. We specifically focus on intrinsic motivation in the field of reading, which is of particular relevance for students’ academic development and participation in society. Relying on a large-scale panel, the first aim of this study is to establish measurement invariance of IRM and perceived TAS across secondary school, which is the prerequisite that is essential for analyzing the longitudinal relationship between these two constructs. The second aim of the present study is to examine the longitudinal relationship of IRM and student-perceived TAS by applying the dual change score model, which has advantages over more frequently used models, such as the cross-lagged panel model (Mund & Nestler, 2020). Given theoretical arguments (Ryan & Deci, 2020) and empirical, but mostly cross-sectional, evidence suggesting that TAS is beneficial for IRM (Bureau et al., 2022), we hypothesize that the trend of declining IRM between fifth and eighth grade is countered by student-perceived TAS.

Methods

Sample

The present study is based on data from the German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS; Blossfeld & Roßbach, 2019; NEPS Network, 2022), which focuses on educational processes and the development of competencies. Data from the NEPS, utilized in our study, have been employed to investigate the decline in intrinsic motivation to read (Miyamoto et al., 2020). However, they have not been utilized to assess whether teacher autonomy support mitigates this decline. The NEPS is conducted under the supervision of the German Federal Commissioner for Data Protection and Freedom of Information (BfDI) and in coordination with the German Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs (KMK) and the educational ministries of the respective federal states. All data collection procedures, instruments, and documents were checked by the data protection unit of the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi). The necessary steps are taken to protect participants’ confidentiality according to national and international regulations of data security. Participation in the NEPS is voluntary and based on the informed consent of the students and their parents. This consent to participate in the NEPS can be revoked at any time. Our sample comprised N = 8,193 secondary school students who were first surveyed in the fall of 2010, when they were in fifth grade, and then annually in the subsequent school years.Footnote 3 We used data from grades five through eight in which both of the relevant constructs, IRM and TAS, were assessed. We included all students for whom data on IRM or perceived TAS was available for at least one wave. Information on missing values and descriptive statistics of all manifest and latent indicators is presented in Table 1. At first measurement, students in our analytical sample were on average 10.39 years old (SD = 0.69). Almost half of the participants were female (48%).

Measures

Teacher autonomy support

To measure perceived TAS in the school subject German, a three-item version of the Learning Climate Questionnaire by Williams & Deci (1996) was used (e.g., “My German teacher tries to understand how I see things before suggesting a new way to do things”; “My German teacher encourages me to ask questions”; “My German teacher listens to my suggestions and takes them seriously”). Students answered the items on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (does not apply at all) to 5 (fully applies) annually from fifth to eighth grade. The internal consistency of the scales was acceptable (ωgrade5 = 0.79; ωgrade6 = 0.81; ωgrade7 = 0.83; ωgrade8 = 0.84).

Intrinsic reading motivation

To assess IRM, six items of the habitual reading motivation questionnaire (HRMQ; Möller & Bonerad, 2007) were used. Following the procedure by Miyamoto et al. (2020), we used four items designed to measure IRM (e.g., “I enjoy reading books”).Footnote 4 These items capture habitual motivation, i.e., students’ interest and enjoyment in reading independent of the context in which they read. Students answered the items on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (do not agree at all) to 4 (completely agree). The internal consistency of the scales was good (ωgrade5 = 0.87; ωgrade6 = 0.89; ωgrade7 = 0.89; ωgrade8 = 0.86).

Statistical analyses

We initially applied confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) probing whether a single-factor structure of IRM and TAS fit the data well. We then tested the longitudinal measurement invariance of IRM and TAS to examine whether observed changes in these factors reflect individual mean-level changes and are not due to structural changes (Miyamoto et al., 2020; van de Schoot et al., 2015). We then specified the dual change score model (DCSM; Grimm et al., 2012; Mund & Nestler, 2018) using MPLUS 8.6 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017) following the instructions provided by Mund & Nestler (2020). The model was estimated using the ML function (maximum likelihood estimation). We report unstandardized parameters as proposed by Mund & Nestler (2018, 2020). Parameter labels are based on Jacobucci et al. (2019) and Little et al. (2017). The full information maximum likelihood method (FIML) was employed to address missing data (Muthén & Muthén, 2017).

For the evaluation of model fit, we relied on the comparative fit index (CFI), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR; Hooper et al., 2008). We relied on well-established cut-off values, in which CFI ≥ 0.95, RMSEA ≤ 0.06, and SRMR ≤ 0.05 indicated a good model fit and CFI > 0.90, RMSEA < 0.08, and SRMR < 0.08 indicated an acceptable model fit (Hooper et al., 2008; Hu & Bentler, 1999). We did not use the chi-square statistics because it is sensitive to large sample sizes (Frenzel et al., 2012; Hooper et al., 2008; Miyamoto et al., 2020).

Longitudinal measurement invariance

We specified three measurement invariance models—i.e., configural, metric, and scalar measurement invariance—for each construct. These three measurement invariance tests vary in the number of parameters that were invariant across the four measurement occasions (Chen, 2007; Christ & Schlüter, 2012; Frenzel et al., 2012; Miyamoto et al., 2020). For evaluating longitudinal measurement invariance, Chen (2007) proposes to compare the change in the models’ (configural, metric, and scalar) CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR values. For testing metric invariance, a change of Δ CFI ≥ 0.010, supplemented by a change of Δ RMSEA ≥ 0.015 and Δ SRMR ≥ 0.030, indicates non-invariance. For testing scalar invariance, a change of Δ CFI ≥ 0.010, Δ RMSEA ≥ 0.015, and Δ SRMR ≥ 0.010 indicates non-invariance (Chen, 2007; Miyamoto et al., 2020). Metric measurement invariance is required for a comparison of change scores or regression slopes in longitudinal analyses, and scalar measurement invariance is required for a comparison of latent mean differences across time (Chen, 2007; Widaman & Reise, 1997).

Dual change score model

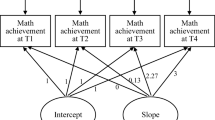

The DCSM (Grimm et al., 2012; Hamagami & McArdle, 2001; Mund & Nestler, 2018) uses a true score formulation for modeling the dynamics and longitudinal trajectories of the variables, in our case perceived TAS and IRM. It measures the mean of a variable at the first measurement occasion (intercepts α1TAS and α1IRM) and the mean level change at the following time points (Mund & Nestler, 2018; Mund et al., 2018). In DCSM, overall change in one variable is broken into three different components of change: a constant change component and two proportional change components. For specifying DCSM, we first defined latent true scores for both variables across the four measurement occasions. Afterward, we defined six latent difference scores (three for each variable) measuring “time-point-to-time-point change” (Little et al., 2017; p: 937) between the first and second, the second and third, and the third and fourth time points. We subsequently specified a latent growth model by defining two growth factors that load on all latent difference variables. These two constant change components (represented by the slopes α2TAS and α2IRM) measure the overall rate of change across all time points (Mund & Nestler, 2018). The autoregressions between the latent true scores for perceived TAS and IRM were set to one. Then, we added the two proportional change components for perceived TAS and IRM. The proportional effects within each variable were represented by βTAS and βIRM. These proportional effects were defined by three regressions for each construct between the difference scores in one variable at the second, third, and fourth measurements and the true scores of the same variable at the previous measurement (i.e., the first, second, and third). Thus, they measure the effects of the levels of construct at one specific time point “on its subsequent time-point-to-time-point change” (Little et al., 2017; p. 938). The proportional effects between the variables, represented by γTAS and γIRM, are modeled by regressions between the true scores of the previous time point in one variable and the change scores in the other variable at the subsequent time point. For instance, γTAS estimates the effect of previous levels of perceived TAS on subsequent changes in IRM. Both proportional change components describe how the change in a variable between adjoining time points depends on the same or other variable’s level at the previous time point and reflect the degree to which constant change is limited or amplified by prior levels of the same, or prior levels of the other variable (Mund & Nestler, 2018). Both types of parameters (βTAS, βIRM and γTAS, γIRM) are time invariant by assumption in our model (Mund & Nestler, 2018). It is further assumed that the variance of the residuals of the latent change score variables is zero.

Estimating the DCSM, “it is assumed that the intercepts of the observed indicators and the means of the true scores, except for the true scores for the first time point, are zero” (Mund & Nestler, 2018, p. 22). The means of the constant change components are freely estimated. The variance of all latent residuals is fixed to zero, except for time point one (Mund & Nestler, 2018). This allows researchers to estimate all correlations between these two true score variables and the latent factors representing the constant change component. The remaining variables are specified to be uncorrelated with these latent variables (Mund & Nestler, 2018). During estimation, the variance terms of the residual scores of the observed indicators are assumed to be equal (Mund & Nestler, 2018).

Results

Tables 2 and 3 show the results of the longitudinal measurement invariance models for the constructs IRM and perceived TAS, respectively. Changes in model fit indices were within predefined limits for both constructs, indicating that scalar measurement invariance is given. Therefore, both latent constructs might be considered appropriate for meaningful comparison of change scores in longitudinal studies and suitable for the comparison of latent mean differences across time.

Figure 1 presents the results of the bivariate DCSM examining the interplay between IRM and perceived TAS from fifth to eighth grade. The model showed good overall fit (CFI = 0.973, RMSEA = 0.038, and SRMR = 0.055). We found a positive and significant correlation between the intercepts of IRM and perceived TAS at the first measurement occasion (rα1 = 0.17; p ≤ 0.001). This finding indicates that students with higher values in perceived TAS tend to show higher values in IRM. To deduce the longitudinal relationship between IRM and perceived TAS, all estimated parameters need to be considered. The intercept of IRM was α1IRM = 3.01, while the intercept of perceived TAS had a value of α1TAS = 3.62. The constant change components of IRM (α2IRM = − 3.71; p = 0.021) and perceived TAS (α2TAS = − 0.94; p = 0.384) were both negative, but only the constant change component of IRM reached statistical significance. Regarding the proportional change components within each construct, we found that the proportional change in IRM was negative and statistically significant (βIRM = − 2.67; p ≤ 0.001), whereas the proportional change in perceived TAS was positive but did not reach statistical significance (βTAS = 1.23; p = 0.053). Cross-lagged effects can be inferred from the proportional change components between IRM and perceived TAS. Our results showed that the path from perceived TAS to the change in IRM was positive and statistically significant (γTAS = 3.18; p = 0.001), while the path from IRM to the change in perceived TAS was negative and statistically significant (γIRM = − 1.28; p = 0.003).

Thus, the bivariate DCSM indicates that the negative constant decrease in students’ IRM over time (α2IRM) is amplified (βIRM) with the more time points that pass. For perceived TAS, the DCSM indicates that the negative, yet non-significant constant decrease over time (α2TAS) is decelerated (non-significantly) with the more time points that pass (βTAS). In addition, the positive cross-lagged effect from TAS to IRM (γTAS) shows that the negative constant change in IRM (α2IRM) is decelerated by earlier levels of perceived TAS. The negative cross-lagged effect from IRM to perceived TAS (γIRM) indicates that prior levels of IRM significantly amplify the negative (non-significant) change in TAS (α2TAS).

Discussion

Given the particular importance of intrinsic motivation in the field of reading for students’ reading achievement (Becker et al., 2010; Guthrie et al., 2004; Schiefele et al., 2012), it is of great practical relevance to identify those instructional features with which teachers can counteract the developmental decline in IRM. SDT suggests that autonomy support provided by teachers is particularly relevant to the development of intrinsic motivation (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2000b). However, empirical evidence to date has been predominantly cross-sectional (Bureau et al., 2022). The existing longitudinal studies either do not explicitly examine TAS or have small sample sizes and cover only short periods (Bureau et al., 2022). The goal of the present study was to provide evidence on the measurement invariance of IRM and TAS based on large-scale panel data from fifth to eighth grade. In addition, we aimed to shed light on the longitudinal relationship between TAS and IRM using DCSM.

Are IRM and student-perceived TAS measurement invariant from grades five to eight?

Our findings confirmed scalar measurement invariance, the most restricted form of measurement invariance, for both IRM and TAS from fifth to eighth grade. These results replicate previous research (Miyamoto et al., 2020) and, from a methodological point of view, extend our knowledge of structural changes in IRM and TAS during adolescence. Thus, by ruling out the occurrence of biases, such as item-specific differences in difficulty over time (Miyamoto et al., 2020; Schwab & Helm, 2015; van De Schoot et al., 2015), our analyses provide an accurate estimate of the longitudinal interplay between IRM and TAS.

Does TAS in the school subject German buffer the decline in students’ IRM from grades five to eight?

Initially, our DCSM showed a developmental decline in students’ IRM across secondary school. This finding is consistent with a large number of studies (Bouffard et al., 2001; Kolić-Vehovec et al., 2014; McElvany et al., 2008; Miyamoto et al., 2020; Schaffner et al., 2016; van de Gaer et al., 2009; Viljaranta et al., 2014). This decline is troubling because reading motivation is fundamental not only to learning in school in all subjects but also to learning outside of school and participation in society. This makes it all the more important that the learning environment at school is designed to encourage the enjoyment of reading.

In addition, we found that TAS did not significantly decrease over time. More specifically, DCSM showed a negative, yet non-significant, trend in TAS. This trend was, however, decelerated over time. To date, there has been little empirical research on changes in how students perceive TAS across secondary school (Diseth et al., 2018; Way et al., 2007), although it is often considered a possible explanation for the developmental decline in students’ IRM across secondary school (e.g., Scherrer & Preckel, 2019). Results from existing research have been mixed. Way et al. (2007) found that US students reported a decline in autonomy support from the school as a whole between sixth and eighth grade. Diseth et al. (2018) found mean level changes in female students’ perception of the TAS provided by several teachers between sixth and eighth grade, but not in male students’ perception. Although autonomy-promoting behaviors considered to be particularly beneficial (Frederick et al., 2022) can be used in a variety of subjects, language arts and social studies—especially in secondary school—may offer more latitude to “allow[] students to choose tasks that align with their priorities” (Frederick et al., 2022, p. 27) than is possible in, say, mathematics. Therefore, more research is needed to gain a better understanding of the development of TAS in different domains across secondary education.

In addition, we found a negative cross-lagged effect from IRM to perceived TAS indicating that prior levels of IRM significantly amplify the negative (non-significant) change in TAS. This finding implies that students with higher IRM perceive a greater decrease in TAS. This result is in line with organismic integration theory, a theory within SDT specifying different motivation types that are thought to vary in their relative autonomy (e.g., Ryan & Deci, 2018; Ryan et al., 2022). According to the theory, intrinsic motivation is seen as the most autonomous regulatory style along a “continuum that spans from relatively heteronomous or controlled regulation to relatively autonomous self-regulation” (Ryan & Deci, 2018, p. 191; see also Ryan et al., 2022). Students who are more intrinsically motivated readers are likely to expect more autonomy support in the German classroom so they perceive even a marginal decrease in autonomy support more strongly than students with less intrinsic motivation. Thus, when examining the development of TAS across secondary school, research must take into account individual differences that may play a role in the perception of TAS.

Most importantly, the present study showed that the negative developmental trend in students’ IRM is buffered by earlier levels of TAS from fifth to eighth grade. Thus, supporting our hypothesis, when students perceive their German teacher as supporting their autonomy at a given point in time, the negative constant change in students’ IRM is decelerated. For instance, students who perceive more TAS in German during fifth grade experience a less pronounced decline in IRM between grades five and six. Our results are in line with the theoretical assumptions of SDT (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2000b), suggesting that intrinsic motivation may be enhanced or maintained when the student’s need for autonomy is satisfied in a certain context. To date, several empirical findings have supported the theoretical assumptions of SDT, suggesting that TAS in a particular domain contributes positively to students’ intrinsic motivation in that domain (Chang et al., 2016), including reading (De Naeghel et al., 2014a, b; Guthrie et al., 2004; Wigfield, 2005). Yet, empirical evidence has mostly been based on cross-sectional data (Bureau et al., 2022) and has not explicitly examined TAS or focused on the domain of reading. Beyond cross-sectional associations, the present study showed the positive effects of TAS on the development of IRM and, thus, we confirmed that TAS may be inherently meaningful for student development.

Limitations and directions for future research

Our study has some limitations that need to be noted. Firstly, we relied on student ratings of TAS, which potentially share method bias with self-reported IRM. Using the same perspective and measurement method can introduce common method variance, i.e., biases resulting from inflated relationships between measures (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Moreover, student ratings of TAS only represent a certain perspective on instructional quality, may be affected by their experiences within the classroom, and reflect the “dyadic relationship between an individual student and one specific teacher” (Göllner et al., 2021, p. 114). They may also be influenced by personal idiosyncrasies (Kunter & Baumert, 2006; Winne et al., 2002). It could be promising to complement student ratings of TAS with ratings by external observers, either using video-based or in-class observations.

Secondly, we present findings on the longitudinal interplay between IRM and TAS using DSCM, a statistical method that explicitly considers developmental changes that do not affect the rank order in a sample. In their recent meta-analysis on SDT, Ryan et al. (2022) pointed out that more longitudinal research is indispensable: “In an era of psychological science that focuses on causal rather than associative links, the knowledge revealed by aggregations of cross-sectional data can be unsatisfying” (p. 835). Nevertheless, causal inferences based on panel data are only permissible if all other prerequisites for causal interpretations are also met (Allison, 2009). However, these prerequisites are “extremely strict [and, therefore], researchers should not expect to ever encounter a situation in which causal inferences from panel data are ultimately possible” (Mund & Nestler, 2020, p. 12). In addition, we did not include control variables and the nested data structure is not addressed in the dual change score model. It should also be noted that while the FIML procedure has been shown to produce unbiased estimates, the percentage of missing data in our study was substantial. Although the results presented here stand out from previous findings because we use a large-scale sample of students studied over 4 years in early adolescence, experimental studies provide more internally valid evidence and are regarded as the “gold standard” with good reason (Rubie-Davies & Rosenthal, 2016).

Thirdly, we used a sample of German secondary school students. Our results can therefore not easily be generalized to elementary and upper secondary school students or other school systems, since theoretical assumptions suggest that students’ desire for autonomy might differ between age groups (Eccles et al., 1993) and empirical findings show that students’ initial levels of perceived TAS might differ between school systems across countries (Chirkov & Ryan, 2001). Further studies should replicate our findings using different age groups and in countries with lower or higher initial levels of perceived TAS. Relatedly, future studies should probe the role of TAS in other domains and examine whether it equally counters declining IRM in different subgroups of students. For instance, students who identify as male have been found to experience steeper declines in IRM than those who identify as female (Miyamoto et al., 2020; Van de Gaer et al., 2009) and could benefit differentially from TAS.

Conclusion and implications for practice

Based on a sample of 8193 fifth graders followed over the course of four school years, our DSCM confirmed the SDT-derived rationale that the developmental decline in students’ intrinsic motivation to read is mitigated by their German teachers’ autonomy support. These findings have important implications for addressing the developmental decline in students’ intrinsic motivation to read, which is essential for all forms of learning. Our quantitative results corroborate the findings of a recent qualitative study indicating that the possibility to choose from more interesting texts would make students more inclined to read at school (Tegmark et al., 2022). By confirming SDT’s suggestion that autonomy support may be particularly essential in maintaining and enhancing intrinsic motivation to read (Ryan & Deci, 2000a), our findings provide guidance on how to design interventions to train teachers in practices that support autonomy. The good news is that teachers can learn to support the autonomy of their students (Reeve & Cheon, 2021; Su & Reeve, 2011) and there are many ways to do it. Giving students a choice (“Feel free to work with a friend or do it by yourself”), teaching in ways that students prefer (“I know you love comics so I based today’s lesson on …”), providing rationales (“Reading this book will help you understand…”), allowing students to work on their own pace, using invitational language (“You may want to try this…”), and asking students for feedback on teaching are the most relevant autonomy supporting practices agreed upon by international experts (Frederick et al., 2022, pp. 27–28). Given that autonomy support from literacy teachers seems to directly affect student engagement in class (Liu et al., 2021) and, thus, may be of even greater importance than autonomy support from teachers in subjects like mathematics, training literacy teachers may be of particular relevance. Overall, adopting autonomy-supporting practices can help teachers increase their students’ IRM and even buffer its developmental decline.

Data availability

We used data from the German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS). The data of the German NEPS is prepared and disseminated in the form of Scientific Use Files to the scientific community by the Research Data Center at the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (RDC-LIfBi). The datasets are available for download from the study website: https://www.neps-data.de/Data-Center/Data-Access/Download

Notes

Bureau and colleagues (2022) categorized two additional studies as longitudinal (Langdon et al., 2017; Niemiec & Muñoz, 2019). These studies measured the longitudinal effects of need supportive teacher training programs while not assessing intrinsic motivation over several measurement occasions. Although Bureau and colleagues’ (2022) classification is therefore reasonable, the information relevant to our study on the simultaneous development of intrinsic motivation and teacher autonomy support across time is missing in these studies.

The study by Scholten (2016) was conducted in the university context.

A refreshment sample of seventh graders was added to the original sample in wave three to compensate the attrition of students in three federal states who entered secondary school at the beginning of seventh grade and, thus, left the school context. For the present study, we relied on both the original and the refreshment samples.

The items we excluded reflect external aspects of reading motivation (Miyamoto et al., 2020).

References

Allison, P. D. (2009). Fixed effects regression models. SAGE.

Becker, M., McElvany, N., & Kortenbruck, M. (2010). Intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation as predictors of reading literacy: A longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(4), 773–785. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020084

Blossfeld, H.-P., & Roßbach, H.-G. (Eds.). (2019). Edition ZfE: Vol. 3. Education as a lifelong process: The German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS) (2nd ed.). Springer VS.

Bouffard, T., Boileau, L., & Vezeau, C. (2001). Students’ transition from elementary to high school and changes of the relationship between motivation and academic performance. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 16, 589–604. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03173199

Bureau, J. S., Howard, J. L., Chong, J. X. Y., & Guay, F. (2022). Pathways to student motivation: A meta-analysis of antecedents of autonomous and controlled motivations. Review of Educational Research, 92(1), 46–72. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543211042426

Cerasoli, C. P., Nicklin, J. M., & Ford, M. T. (2014). Intrinsic motivation and extrinsic incentives jointly predict performance: A 40-year meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 980–1008. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035661

Chang, Y.-K., Chen, S., Tu, K.-W., & Chi, L.-K. (2016). Effect of autonomy support on self-determined motivation in elementary physical education. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 15, 460–466.

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

Chirkov, V. I., & Ryan, R. M. (2001). Parent and teacher autonomy-support in Russian and US adolescents: Common effects on well-being and academic motivation. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(5), 618–635.

Christ, O., & Schlüter, E. (2012). Mplus - Multiple Gruppenvergleiche [Mplus- Multiple group comparisons]. In O. Crist & E. Schlüter (Eds.), Strukturgleichungsmodelle mit Mplus [Structural equation modeling with Mplus] (pp. 59–84). Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag.

De Naeghel, J., Valcke, M., De Meyer, I., Warlop, N., van Braak, J., & Van Keer, H. (2014a). The role of teacher behavior in adolescents’ intrinsic reading motivation. Reading and Writing, 27, 1547–1565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-014-9506-3

De Naeghel, J., Van Keer, H., & Vanderlinde, R. (2014b). Strategies for promoting autonomous reading motivation: A multiple case study research in primary education. Frontline Learning Research, 3, 83–101. https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v2i1.84

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum Press.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1987). The support of autonomy and the control of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(6), 1024–1037.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behaviour. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Diseth, Å., Breidablik, H. J., & Meland, E. (2018). Longitudinal relations between perceived autonomy support and basic need satisfaction in two student cohorts. Educational Psychology, 38(1), 99–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2017.1356448

Eccles, J. S., Midgely, C., Wigfield, A., Buchanan, C. M., Reuman, D., Flanagan, C., & Mac Iver, D. (1993). Development during adolescence: The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and families. American Psychologist, 48(2), 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.48.2.90

Frederick, C. M., Ahmadi, A., Noetel, M., Parker, P., & Ntoumanis, N. (2022). A classification system for teachers’ motivational behaviours recommended in self-determination theory interventions. Journal of Educational Psychology. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/4vrym

Frenzel, A. C., Pekrun, R., Dicke, A.-L., & Goetz, T. (2012). Beyond quantitative decline: Conceptual shifts in adolescents’ development of interest in mathematics. Developmental Psychology, 48(4), 1069–1082. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026895

Gillet, N., Vallerand, R. J., & Lafrenière, M. A. K. (2012). Intrinsic and extrinsic school motivation as a function of age: The mediating role of autonomy support. Social Psychology of Education, 15, 77–95.

Göllner, R., Fauth, B., & Wagner, W. (2021). Student ratings of teaching quality dimensions: Empirical findings and future directions. In W. Rollett, H. Bijlsma, & S. Röhl (Eds.), Student feedback on teaching in schools: Using student perceptions for the development of teaching and teachers (pp. 111–122). Springer.

Gottfried, A. E., Fleming, J. S., & Gottfried, A. W. (2001). Continuity of academic intrinsic motivation from childhood through late adolescence: A longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-0663.93.1.3

Grimm, K. J., An, Y., McArdle, J. J., Zonderman, A. B., & Resnick, S. M. (2012). Recent changes leading to subsequent changes: Extensions of multivariate latent difference score models. Structural Equation Modeling, 19, 268–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2012.659627

Guthrie, J. T., Wigfield, A., Barbosa, P., Perencevich, K. C., Taboada, A., Davis, M. H., Scafiddi, N. T., & Tonks, S. (2004). Increasing reading comprehension and engagement through concept-oriented reading instruction. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(3), 403–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.3.403

Hagger, M. S., Sultan, S., Hardcastle, S. J., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. D. (2015). Perceived autonomy support and autonomous motivation toward mathematics activities in educational and out-of-school contexts is related to mathematics homework behavior and attainment. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41, 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2014.12.002

Hamagami, F., & McArdle, J. J. (2001). Advanced studies of individual differences linear dynamic models for longitudinal data analysis. In G. A. Marcoulides & R. E. Schumacker (Eds.), New developments and techniques in structural equation modeling (pp. 203–246). Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.21427/D7CF7R

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Jacobucci, R., Serang, S., & Grimm, K. J. (2019). A short note on interpretation in the dual change score model. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 26(6), 924–930. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2019.1619457

KMK [Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs]. (2022). Bildungsstandards für das Fach Deutsch: Erster Schulabschluss (ESA) und Mittlerer Schulabschluss (MSA) (Beschluss der Kultusministerkonferenz vom 15.10.2004 und vom 04.12.2003, i.d.F. vom 23.06.2022) [Educational standards for the school subject German: First school-leaving-qualification (ESA) and intermediate education examination (MSA) (Resolution of the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs from 15.10.2004 and 04.12.2003 in the version dated 23.06.2022)]. https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/veroeffentlichungen_beschluesse/2022/2022_06_23-Bista-ESA-MSA-Deutsch.pdf

Kolić-Vehovec, S., Rončević Zubković, B., & Pahljina-Reinić, R. (2014). Development of metacognitive knowledge of reading strategies and attitudes toward reading in early adolescence: The effect on reading comprehension. Psihologijske Teme, 23(1), 77–98.

Kriegbaum, K., Becker, N., & Spinath, B. (2018). The relative importance of intelligence and motivation as predictors of school achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 25(1), 120–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2018.10.001

Kunter, M., & Baumert, J. (2006). Who is the expert? Construct and criteria validity of student and teacher ratings of instruction. Learning Environments Research, 9, 231–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-006-9015-7

Langdon, J., Schlote, R., Melton, B., & Tessier, D. (2017). Effectiveness of a need supportive teaching training program on the developmental change process of graduate teaching assistants’ created motivational climate. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 28, 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.09.008

Lau, K. L. (2016). Within-year changes in Chinese secondary school students’ perceived reading instruction and intrinsic reading motivation. Journal of Research in Reading, 39(2), 153–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9817.12035

Little, C. W., Hart, S. A., Quinn, J. M., Tucker-Drob, E. M., Taylor, J., & Schatschneider, C. (2017). Exploring the co-development of reading fluency and reading comprehension: A twin study. Child Development, 88(3), 934–945. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44250127

Liu, H., Yao, M., Li, J., & Li, R. (2021). Multiple mediators in the relationship between perceived teacher autonomy support and student engagement in math and literacy learning. Educational Psychology, 41(2), 116–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2020.1837346

McElvany, N., Kortenbruck, M., & Becker, M. (2008). Lesekompetenz und Lesemotivation: Entwicklung und Mediation des Zusammenhangs durch Leseverhalten [Reading literacy and reading motivation: Their development and the mediation of the relationship by reading behavior]. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie, 22(34), 207–219. https://doi.org/10.1024/1010-0652.22.34.207

Miyamoto, A., Pfost, M., & Artelt, C. (2018). Reciprocal relations between intrinsic reading motivation and reading competence: A comparison between native and immigrant students in Germany. Journal of Research in Reading, 41(1), 176–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9817.12113

Miyamoto, A., Murayama, K., & Lechner, C. M. (2020). The developmental trajectory of intrinsic reading motivation: Measurement invariance, group variations, and implications for reading proficiency. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 63, 101921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101921

Möller, J., & Bonerad, E. M. (2007). Fragebogen zur habituellen Lesemotivation [Habitual reading motivation questionnaire]. Psychologie in Erziehung Und Unterricht, 54, 259–267.

Mund, M., & Nestler, S. (2018). Beyond the cross-lagged panel model: Next-generation statistical tools for analyzing interdependencies across the life course. Advances in Life Course Research. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/zfy85

Mund, M., & Nestler, S. (2020). Beyond the cross-lagged panel model: Next-generation statistical tools for analyzing interdependencies across the life course [Data file and analysis syntax]. OSF. https://osf.io/sjph7

Mund, M., Zimmermann, J., & Neyer, F. J. (2018). Personality development in adulthood. In V. Zeigler-Hill & T. K. Shackelford (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of personality and individual differences (pp. 260–277). Sage.

Muthén, L.K., & Muthén, B.O. (2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthen & Muthen.

NEPS Network. (2022). National educational panel study: scientific use file of starting cohort grade 5 [Data set]. Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi). https://doi.org/10.5157/NEPS:SC3:10.0.0

Niemiec, C. P., & Muñoz, A. (2019). A need-nupportive intervention delivered to English language teachers in Colombia: A pilot investigation based on self-determination theory. Psychology, 10(07), 1025.

Núñez, J. L., & León, J. (2015). Autonomy support in the classroom: A review from self-determination theory. European Psychologist, 20(4), 275–283. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000234

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Ratelle, C. F., Guay, F., Vallerand, R. J., Larose, S., & Senécal, C. (2007). Autonomous, controlled and amotivated types of academic motivation: A person-oriented analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(4), 734–746. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.4.734

Reeve, J., & Cheon, S. H. (2021). Autonomy-supportive teaching: Its malleability, benefits, and potential to improve educational practice. Educational Psychologist, 56(1), 54–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2020.1862657

Reeve, J., Jang, H., Carrell, D., Jeon, S., & Barch, J. (2004). Enhancing students’ engagement by increasing teachers’ autonomy support. Motivation and Emotion, 28(2), 147–169. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:MOEM.0000032312.95499.6f

Rubie-Davies, C. M., & Rosenthal, R. (2016). Intervening in teachers’ expectations: A random effects meta-analytic approach to examining the effectiveness of an intervention. Learning and Individual Differences, 50, 83–92.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000a). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54–67.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000b). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2018). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Press.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

Ryan, R. M., Duineveld, J. J., Di Domenico, S. I., Ryan, W. S., Steward, B. A., & Bradshaw, E. L. (2022). We know this much is (meta-analytically) true: A meta-review of meta-analytic findings evaluating self-determination theory. Psychological Bulletin, 148(11–12), 813–842. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000385

Savard, A. (2013). Academic and social adjustment of teenagers in social rehabilitation: The role of intrinsic need satisfaction and autonomy support (Publication No. NR79299) [Doctoral dissertation, Université de Montréal]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Schaffner, E., Philipp, M., & Schiefele, U. (2016). Reciprocal effects between intrinsic reading motivation and reading competence? A cross-lagged panel model for academic track and nonacademic track students. Journal of Research in Reading, 39(1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9817.12027

Scherrer, V., & Preckel, F. (2019). Development of motivational variables and self-esteem during the school career: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Review of Educational Research, 89(2), 211–258. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654318819127

Schiefele, U., & Schaffner, E. (2016). Factorial and construct validity of a new instrument for the assessment of reading motivation. Reading Research Quarterly, 51(2), 221–237. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.134

Schiefele, U., Schaffner, E., Möller, J., & Wigfield, A. (2012). Dimensions of reading motivation and their relation to reading behavior and competence. Reading Research Quarterly, 47(4), 427–463. https://doi.org/10.1002/RRQ.030

Schiefele, U., Stutz, F., & Schaffner, E. (2016). Longitudinal relations between reading motivation and reading comprehension in the early elementary grades. Learning and Individual Differences, 51, 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.08.031

Scholten, R. (2016). Effects of a self-determination theory based intervention in university statistics education (Master’s thesis, Leiden University). Leiden University Student Repository. https://hdl.handle.net/1887/40173. Accessed 24 Mar 2023.

Schwab, S., & Helm, C. (2015). Überprüfung von Messinvarianz mittels CFA und DIF-Analysen [Testing measurement invariance using CFA and DIF analyses]. Empirische Sonderpädagogik, 3, 175–193.

Simon, P. D., & Salanga, M. G. C. (2021). Validation of the Five item Learning Climate Questionnaire as a measure of teacher autonomy support in the classroom. Psychology in the Schools, 58, 1919–1931. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22546

Su, Y. L., & Reeve, J. (2011). A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of intervention programs designed to support autonomy. Educational Psychology Review, 23, 159–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-010-9142-7

Taylor, G., Jungert, T., Mageau, G. A., Schattke, K., Dedic, H., Rosenfield, S., & Koestner, R. (2014). A self-determination theory approach to predicting school achievement over time: The unique role of intrinsic motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 39(4), 342–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2014.08.002

Tegmark, M., Alatalo, T., Vinterek, M., & Winberg, M. (2022). What motivates students to read at school? Student views on reading practices in middle and lower-secondary school. Journal of Research in Reading, 45, 100–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9817.12386

Van de Gaer, E., Pustjens, H., Van Damme, J., & De Munter, A. (2009). School engagement and language achievement: A longitudinal study of gender differences across secondary school. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 55(4), 2.

van De Schoot, R., Schmidt, P., De Beuckelaer, A., Lek, K., & Zondervan-Zwijnenburg, M. (2015). Measurement invariance. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1064. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01064

Viljaranta, J., Tolvanen, A., Aunola, K., & Nurmi, J. E. (2014). The developmental dynamics between interest, self-concept of ability, and academic performance. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 58(6), 734–756. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2014.904419

Wang, C. J., Liu, W. C., Kee, Y. H., & Chian, L. K. (2019). Competence, autonomy, and relatedness in the classroom: Understanding students’ motivational processes using the self-determination theory. Heliyon, 5(7). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01983

Way, N., Reddy, R., & Rhodes, J. (2007). Students’ perceptions of school climate during the middle school years: Associations with trajectories of psychological and behavioral adjustment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 40, 194–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-007-9143-y

Widaman, K. F., & Reise, S. P. (1997). Exploring the measurement invariance of psychological instruments: Applications in the substance use domain. In K. J. Bryant, M. Windle, & S. G. West (Eds.), The science of prevention: Methodological advances from alcohol and substance abuse research (pp. 281–324). American Psychological Association.

Wigfield, A. (2005). Concept oriented reading instruction – CORI. Ein Programm zur Förderung der Lesemotivation im Unterricht [Influence of concept oriented reading instruction on children’s motivation for reading]. Unterrichtswissenschaft, 33(2), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:5789

Williams, G. C., & Deci, E. L. (1996). Internalization of biopsychosocial values by medical students: A test of self-determination theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 767–779. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.4.767

Winne, P., Jamieson-Noel, D., & Muis, K. (2002). Methodological issues and advances in researching tactics, strategies, and self-regulated learning. In P. R. Pintrich & M. L. Maehr (Eds.), Advances in motivation and achievement: New directions in measures and methods (pp. 121–155). Elsevier Science.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Current themes of research:

Student motivation.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education:

No previous publications.

Andrea Westphal

Current themes of research:

Teacher professionalization. Teachers’ instructional practices. Teacher self-efficacy and burnout. Emotions in teaching and learning.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education:

Westphal, A., Kretschmann, J., Gronostaj, A., & Vock, M. (2018). More enjoyment, less anxiety and boredom: How achievement emotions relate to academic self-concept and teachers’ diagnostic skills. Learning and Individual Differences, 62, 108-117.

Westphal, A., Kalinowski, E., Hoferichter, C. J., & Vock, M. (2022). K− 12 teachers’ stress and burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 920326.

Westphal, A., Richter, E., Lazarides, R., & Huang, Y. (2024). More I-talk in student teachers’ written reflections indicates higher stress during VR teaching. Computers & Education, 212, 104987.

Westphal, A., Becker, M., Vock, M., Maaz, K., Neumann, M., & McElvany, N. (2016). The link between teacher-assigned grades and classroom socioeconomic composition: The role of classroom behavior, motivation, and teacher characteristics. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 46, 218-227.

Laura Engler and Andrea Westphal have shared first authorship.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Engler, L., Westphal, A. Teacher autonomy support counters declining trend in intrinsic reading motivation across secondary school. Eur J Psychol Educ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-024-00842-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-024-00842-5