Abstract

Although several longitudinal studies have confirmed that need-supportive teacher behaviour shapes intrinsic motivation in school, longitudinal studies on its role for intrinsic reading motivation are lacking. To fill in this gap, this study investigated whether changes in selected aspects of student-perceived teacher need-supportive behaviour in German lessons predicted changes in intrinsic reading motivation. We also investigated how student intrinsic reading motivation and perceived teacher need-supportive behaviour changed over the course of lower secondary school. To this end, we used data of 7634 German students gathered between Grades 5 and 9 as part of the German National Educational Panel Study, five measurement occasions in total. The analyses, which involved univariate latent change score and change–change models, revealed decreases in perceived teacher need-supportive behaviour and intrinsic motivation between Grades 5 and 9. Moreover, the decreases in perceived teacher need-supportive behaviour in German lessons predicted decreases in intrinsic reading motivation. The study provides first evidence of longitudinal relationships between perceived teacher behaviour and intrinsic reading motivation. It also suggests that adjusting the classroom learning environment to student needs may contribute to alleviating the decrease in intrinsic reading motivation observed in multiple studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Intrinsic motivation is a psychological desire to pursue an activity for enjoyment, satisfaction, and pleasure associated with it (Ryan & Deci, 2017). In students, intrinsic motivation is associated with higher school achievement, better mental health, and increased well-being. Moreover, intrinsically motivated students are more persistent, have higher self-efficacy, and higher self-esteem (see Howard et al., 2021 for a meta-analysis).

The importance of intrinsic motivation for achievement is very well documented for reading. Intrinsically motivated students read more (e.g., Becker et al., 2010; Schaffner et al., 2013) and have higher reading competence (e.g., Toste et al., 2020). Since reading is a key element of school learning and constitutes a fundamental skill that underlies competence development in all school subjects (Snow & Biancarosa, 2003), higher intrinsic motivation in reading can benefit overall student achievement. At the same time, past research has revealed a decline in intrinsic reading motivation as students grow older (see Scherrer & Preckel, 2019 for a meta-analysis). Considering the key role that intrinsic reading motivation plays for reading competence and overall school achievement, understanding the reasons behind the decline is essential for designing learning environments that are conducive to both. Meanwhile, the school learning environment is the only context in which intrinsic reading motivation can be systematically addressed and fostered in all students, irrespective of the support for motivation that they receive in other learning environments (e.g., at home). Since both theory (e.g., Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006) and research (e.g., Scheerens, 2016) have suggested that factors proximal to the teaching and learning process, in contrast to distal factors at the level of school or education system, play the greatest role for student outcomes, this study focuses on teacher behaviour.

Several longitudinal studies have confirmed that teacher behaviour or more broadly—the school learning environment—shapes intrinsic motivation in school (e.g., Gnambs & Hanfstingl, 2016; Maulana et al., 2016). However, longitudinal studies on the role of such factors for intrinsic reading motivation are lacking. Although cross-sectional research on the topic (e.g., De Naeghel et al., 2014; Haw & King, 2022; You et al., 2016) has confirmed the role of teacher need-supportive behaviour, it contributes mostly to a better understanding of between-person differences. Meanwhile, research on the roots of intrinsic motivation, including intrinsic reading motivation, and a lot of research in psychology and education in general, aims at explaining intra-individual change instead of between-person differences, which cannot be achieved with cross-sectional studies. In other words, they seek to shed light on whether changes in the environment or within the individual translate into changes in other aspects of their functioning (see e.g., Berry & Willoughby, 2016). For example, they aim at understanding whether a decrease in need-supportive teacher practices in lessons in the language of instruction explains the decrease in student intrinsic reading motivation observed in past research.

In this vein, this study seeks to verify longitudinal links between selected aspects of the classroom learning environment and intrinsic reading motivation. It investigates whether changes in selected aspects of student-perceived teacher support for autonomy, relatedness, and competence in German lessons predict changes in student intrinsic reading motivation over time. To this end, the study uses a longitudinal panel sample of German lower secondary school students surveyed at five measurement occasions between Grades 5 and 9. To verify hypotheses on intra-individual change, the study employs a latent change–change model.

Developmental decrease in intrinsic reading motivation

Multiple studies have revealed a decline in intrinsic motivation, including intrinsic reading motivation, over the course of schooling. According to the meta-analysis by Scherrer and Preckel (2019), school-related intrinsic motivation decreases by 0.20 SD every 1.66 years. The decrease in intrinsic reading motivation may be even more pronounced. Miyamoto et al. (2020) reported intrinsic reading motivation in German lower secondary school students to decline by 0.78 SD between Grades 5 and 10. The decline is worrying because of the role that intrinsic reading motivation plays for reading competence (Toste et al., 2020), which remains a prerequisite for learning in other subjects (Snow & Biancarosa, 2003).

Although the reasons behind the decrease are not fully understood, there is a consensus that it least partially stems from the school and classroom learning environments not providing adequate instructional quality (e.g., Guthrie & Wigfield, 2017) or not addressing adequately students’ needs as students grow older and move through the education system (e.g., Eccles et al., 1993; Ryan & Deci, 2017).

The role of teacher need-supportive behaviour

A theory that indicates potential classroom-related reasons behind the decrease in intrinsic reading motivation is Cognitive Evaluation Theory, a mini-theory developed as part of self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017, 2020). According to the theory, external events as well as intra- and interpersonal contexts enhance or diminish intrinsic motivation depending on whether they increase or thwart the feeling of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. The feeling of autonomy refers to the experience of whether an activity is pursued out of own willingness or because some external factors enforce it, whereas the feeling of competence is one’s own perceived ability to perform a task effectively. The two are key for the development of intrinsic motivation, but should also be accompanied by interpersonal contexts that support the satisfaction of psychological needs (including the need for relatedness). Since the feelings of autonomy, support, and relatedness depend on external factors, the behaviour of various actors may affect motivation via their effect on these experiences (Ryan & Deci, 2017, 2020).

In the school context, teachers play an important role in shaping the feelings of autonomy, support, and relatedness through behaviour that supports them (referred later as to teacher need-supportive behaviour). Teacher autonomy-supportive behaviours include, among others, allowing students to have a say and choice in learning activities, providing rationales for pursued activities as well as minimising pressures on performance and general coercion in the classroom. Teacher behaviours that provide support for competence are, for instance, providing clear learning goals and high expectations for student effort, having consistent rules, and providing well-structured and adequately challenging tasks that allow students to develop new skills and therefore develop sense of efficacy (Ryan & Deci, 2020). With respect to interpersonal context, teacher behaviours that show care and interest in the students, as well as learning activities that promote interactions and collaboration between students instead of competition (e.g., group work, help-seeking, opportunities to share ideas), facilitate the satisfaction of the need for relatedness (e.g., Ryan & Deci, 2020; Ryan & Patrick, 2001). The theory also indicates that intrapersonal factors (e.g., ego involvement) affect the feeling of autonomy (Ryan & Deci, 2017). However, they are beyond the scope of this study and therefore will not be described in detail.

However, not exactly how a teacher behaves but how their behaviour is perceived by the student is crucial for student intrinsic motivation. In other words, not events or circumstances themselves but their interpretation (functional significance) as controlling or autonomy-supportive affects intrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2017). As a result, the way students see teacher behaviour, as opposed to the way external observers or teachers themselves see it, should be most predictive for student intrinsic motivation. Choosing an adequate perspective is key because student, teacher, and observer perceptions of teacher behaviour differ, which often results in discrepant reports (e.g., Fauth et al., 2020).

Perceived teacher behaviour and its link to motivation

Past research has revealed that students, as they grow older, perceive teacher behaviour or more broadly—the school and classroom environment—as increasingly less supportive. For example, Way et al. (2007) reported a decrease in student-reported teacher and peer support, student decision-making, clarity and consistency of rules, which represent selected aspects of the classroom environment supportive for relatedness, autonomy, and competence, between Grades 6 and 8 in a US sample. In a study on another sample of US students, Gentry et al. (2002) reported a decline in student-perceived choice in the classroom, an aspect of autonomy support, between Grades 3 and 8. Similar decreases but over shorter periods and in European samples have been reported for, for instance, teacher emotional support (Lazarides et al., 2021), representing an aspect of support for relatedness, or shared control in the classroom (Maulana et al., 2016). These results suggest that teacher need-supportive behaviour may indeed decline as students grow older and therefore, it may contribute to the observed decline in intrinsic motivation.

In line with Cognitive Evaluation Theory, several (mostly cross-sectional) studies have confirmed the link between teacher behaviour and intrinsic reading motivation. For example, Haw and King (2022), who used PISA 2018 data gathered from over 578,000 15-year-olds in 76 countries and regions, found that need-supportive teaching predicted intrinsic reading motivation. Based on the analysis of PISA 2009 data, De Naeghel et al. (2014) reported that student-perceived autonomy-supportive, structured, and involved teacher behaviour was positively associated with intrinsic reading motivation among Flemish 15-year olds. In turn, You et al. (2016) reported that the more Korean students perceived their reading teacher to motivate them in Grade 7, the higher their intrinsic reading motivation was a year later.

In line with the above mentioned theory and research, we expected a decrease in intrinsic reading motivation and selected aspects of student-perceived teacher support for autonomy, relatedness, and competence in German lessons over time. Moreover, we hypothesised the decreases in student-perceived need-supportive teacher behaviour to predict decreases in intrinsic reading motivation.

Method

Data and sample

This study uses data from the German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS, Blossfeld & Roßbach, 2019; NEPS Network, 2022). NEPS is a multi-cohort nationwide research project that follows people of different ages, from newborns to the elderly, to better understand how their educational and occupational trajectories unfold over the life course. We used data from Starting Cohort Grade 5 (NEPS-SC3), which comprises students who started Grade 5 in the school year 2010/2011 and have been followed since then.

In this study, we used data from Waves 1 to 5. The sample was drawn using a two-stage cluster sampling method. First, German lower secondary schools were split into six strata representing school types. Within each stratum, schools were selected systematically (due to implicit stratification by federal state, region, and organizing institution) with a probability proportional to their size. Next, two Grade 5 classes were sampled at random from each school if at least three classes were present. If there were one or two classes, they all were sampled (Aßmann et al., 2019). The sample in Wave 1 (2010) included 6112 students attending regular and special needs schools. Since some of the students left schools in which they were surveyed and could not be further followed, a refreshment sample was drawn (N = 2025) in Wave 3. Further information on the sampling design is available in Aßmann et al. (2019) and on panel selectivity and attrition in Zinn et al. (2020). Information on field times along with information on the population of German students is available in Table 1S in the online supplement.

The analytical sample in this study includes students from both original and refreshment samples who attended regular schools (as opposed to special needs schools) and had data on intrinsic reading motivation in at least one wave; 7634 students in total. Students sampled in Wave 1 were aged 10 years 4 months (SD = 6.2 months) at the beginning of Wave 1, whereas students sampled in Wave 3 were aged 12 years 11 months (SD = 6.6 months) at the beginning of Wave 3. In total, 48.40% of the students were female, 22.27% spoke a native language other than German (missing data for 4.47%), and 40.82% attended an academic track school over the included waves of the study (6.15% switched tracks). With respect to socio-economic background, 21.00% had at least one parent with a university degree (missing data for 31.83%) and their parents’ position on the International Socio-Economic Index of Occupational Status Index (ISEI-08, Ganzeboom et al., 1992) ranged from 11.56 to 88.96, with the average of 57.72, SD = 11.74 (missing data for 32.85%).

Procedure

The students were surveyed in schools during regular school hours using paper-and-pencil questionnaires or, if they switched schools and therefore were followed individually, via telephone. All participants of age and legal guardians of underage participants provided written informed consent prior to study enrolment. All participants could withdraw from the study at any time. The NEPS study is conducted under the supervision of the German Federal Commissioner for Data Protection and Freedom of Information (BfDI) and in coordination with the German Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs (KMK) and—in the case of surveys at schools—the Educational Ministries of the respective Federal States. All data collection procedures, instruments, and documents were checked by the data protection unit of the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi). The necessary steps are taken to protect participants’ confidentiality according to national and international data security regulations.

Measures

Intrinsic reading motivation

Intrinsic reading motivation was reported yearly by the students. The scale included four items selected from the Habitual Reading Motivation Questionnaire (Möller & Bonerad, 2007), an established German scale with well-documented validity and reliability. Information on how the items were selected from the original scale can be found in Miyamoto et al. (2020). They referred to reading enjoyment and reading for its own sake (e.g., “I find reading interesting.”) and used a four-point response scale from completely disagree to completely agree. The scale’s internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) in the analytical sample ranged between .835 and .881 depending on the wave.

Perceived teacher support for the three basic needs

Perceived teacher support for autonomy was reported yearly with three items based on Hardre and Reeve’s research (2003). The students declared to what extent they agreed or disagreed with statements on behaviours indicative of their German teacher being supportive of autonomy and taking the student’s perspective into account (e.g., “My German teacher listens to my suggestions and takes them seriously.”). The scale’s internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) in the analytical sample ranged between .787 and .841 depending on the wave.

Perceived support for relatedness was measured yearly with three items on student-perceived teacher support for classroom interactions that came from Ryan and Patrick (2001). The items referred to teacher behaviour that aimed at promoting collaboration end exchange between students (e.g., “My German teacher encourages us to help each other in class.”). The scale’s Cronbach’s α in this study varied from .781 and .860 depending on the wave.

Perceived support for competence was operationalized as student-perceived teacher expectations. They were measured yearly with two items from the DESI study (Wagner et al., 2009). The students declared whether their German teacher had high expectations with respect to effort and hard work (e.g., “My German teacher expects me to try my very best.”). The scale’s Cronbach’s α in this study varied from .648 and .707 depending on the wave. All items used a five-point response scale from does not apply at all to applies completely.

Statistical analyses

In the first step, we ran a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to test the longitudinal measurement invariance (Geiser, 2013) of the four scales used in this study. We started from configural invariance, with parameters estimated freely across measurement occasions and incrementally constrained factor loadings (metric invariance) and intercepts (scalar invariance) to equality and verified whether imposing constraints worsened model fit. Repeated administrations of the same item were allowed to covary. Comparing means of latent factors requires at least partial scalar invariance.

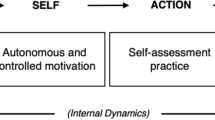

In the second step, we estimated latent change score models (LCS) for intrinsic reading motivation, perceived support for autonomy, relatedness, and competence separately, four models in total. The models allowed us to investigate changes in each variable over time, which was necessary for the correct interpretation of the results of change–change models estimated in the next step. An LCS is schematically presented in Fig. 1. We chose the neighbour change version in which the change score variables (denoted by Δ) represent interindividual differences in intraindividual change between two consecutive (neighbouring) measurement occasions (Geiser, 2013; Steyer et al., 2000). A positive change score indicates an average increase whereas a negative change score indicates an average decrease. The models included parameter constraints selected as final in the measurement invariance analysis. The repeated administrations of the same item were allowed to covary. Please note that the latent change score model for a variable was a reformulation of a CFA model for that variable (Steyer et al., 2000). Since all four variables were measured five times, each model included four change score variables.

In the third step, we estimated a change–change model, which allowed us to verify the hypotheses on the relationships between changes. In the model, changes in perceived support for autonomy, relatedness, and competence predicted changes in intrinsic reading motivation; the initial level of reading motivation was regressed on the initial level of all predictors. Moreover, all exogenous latent variables and repeated items were allowed to covary.

All models used the robust maximum likelihood estimator (MLR). The scales of the latent factors were identified by fixing the first factor loading to unity and the intercept of the first indicator to 0. We assumed that the comparative fit index (CFI) and the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) values not lower than 0.95, the standardized root mean squared residual (RMSEA) not higher than 0.06, and the standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) not higher than 0.08 indicated a good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). With respect to measurement invariance, we followed recommendations by Chen (2007) and assumed that a decrease in CFI ≥ 0.010 supplemented by an increase in RMSEA ≥ 0.015 or an increase in SRMR ≥ 0.030 indicated metric non-invariance. In turn, a decrease in CFI ≥ 0.010 supplemented by an increase in RMSEA ≥ 0.015 or an increase in SRMR ≥ 0.01 indicated scalar non-invariance.

Nesting of data

This study focuses on student-perceived teacher behaviour. However, the data that we used had a nested structure, which usually requires modelling student responses at the individual and classroom levels. Doing so was impossible in this study because NEPS-SC3 data include only cross-sectional class identifiers (Skopek et al., 2012). This was also the reason why we were unable to account for the nested structure of the data by using clustered standard errors. Moreover, many students switched schools and were followed individually and therefore were the only students from their classes who participated in the study. At the same time, among students who remained in their schools, the average class sizes in subsequent waves were low (between 11.69 in Grade 5 and 5.92 in Grade 9), which put into question whether the available student responses adequately represented whole classes. To get a better insight into clustering, we calculated cross-sectional intraclass correlation coefficients ICC1 and ICC2 (see e.g., Lüdtke et al., 2011) for all scales based on raw mean scores. The values of ICC1, depending on the wave, ranged between .092 and .139 for intrinsic reading motivation, between .085 and .217 for autonomy support, between .125 and .228 for support for relatedness, and between .052 and .154 for support for competence. These values suggested that there would have been enough between-class variance to estimate two-level models if longitudinal class identifiers had been available. However, ICC2s, representing the reliability at the class level, only occasionally reached acceptable values (see Klein et al., 2000). They ranged, depending on the wave, between .484 and .581 for reading motivation, between .493 and .627 for autonomy support, between .373 and .547 for support for competence, and between .449 and .757 for support for relatedness.

Missing data

In general, missingness was sizable. It stemmed from the study design (adding a refreshment sample during the course of the study), wave non-participation, and attrition. A total of 36.84% of the students had data on intrinsic reading motivation at all five measurement occasions; 35.22% had complete data on autonomy support, 35.32% had complete data on support for relatedness, and 37.01% had complete data on support for competence. Table 2S in the online supplement contains further information on the completeness of the data. The percentage of students without data in a given wave ranged between 19.14% (Wave 3) and 30.15% (Wave 2) for intrinsic reading motivation, between 16.54% (Wave 3) and 38.45% (Wave 2) for autonomy support, between 16.35% (Wave 2) and 38.35% (Wave 3) for support for relatedness, and between 15.71% (Wave 3) and 37.32% (Wave 2) for support for competence. Table 1S in the online supplement contains further information on the number of cases in each wave.

Missing data were handled using full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) because it allowed us to use information on all available cases and is appropriate even if missingness is sizable (Enders, 2010). FIML provides unbiased estimates under the assumption that that data are missing at random or—in other words—that missingness depends on the variables in the model but not on the values of the variable with missing values (Enders, 2010). Including multiple measurements of the same variable in a model protects against the violation of this assumption because missingness is allowed to depend on the values of the same variable collected at a different measurement occasion (e.g., Marsh et al., 2022). However, to further increase the probability that the missing-at-random assumption held, the models included manifold missing data correlates added as auxiliary variables (Muthén et al., 2016). These were achievement in reading, spelling, maths, science, and ICT in selected waves, school grades, student satisfaction with school, and SES-related variables (parental ISEI, the number of books at home). The auxiliary variables were selected based on preliminary analyses of missing data correlates (not presented here). Since these analysis revealed various missing data correlates, the data were not missing completely at random (MCAR). Therefore, we did not rerun the models using complete cases only as sensitivity analyses because such analyse relied on the assumption that the data were MCAR. Since the assumption was violated, a complete-case analysis would yield biased results.

Transparency and openness

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (https://www.neps-data.de/Data-Center/Data-Access). Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which is the reason why they cannot be provided by the authors of the study. Survey questionnaires are available on the NEPS study website (https://www.neps-data.de/Data-Center/Data-and-Documentation). Main analyses were run in Mplus 8.8, whereas data preparation and basic analyses (e.g., scale reliabilities) were carried out in Stata 16.1. The analysis code for one LCS and the change–change model is available in the online supplement. The study’s design and its analysis were not pre-registered.

Results

Longitudinal measurement invariance

Confirmatory factor analyses revealed that the scales measuring intrinsic reading motivation and autonomy support were scalarly invariant over the waves. The remaining scales were metrically invariant but it was possible to establish partial scalar invariance by freeing one (perceived support for competence) or three (perceived support for relatedness) item intercepts. Table 3S in the online supplement presents detailed information on invariance testing.

Changes in perceived teacher behaviour and intrinsic reading motivation

Correlations between variables in the study are available in Table 2. The latent change score models, estimated to investigate changes in intrinsic reading motivation, support for autonomy, relatedness, and competence over lower secondary school, fit the data well (see Table 1). Overall, they revealed decreases in the four student characteristics between Grades 5 and 9, which is depicted in Fig. 2 (see Table 4S in the online supplement for further details). However, the decreases were not uniform. The greatest decrease in all variables occurred between Grades 5 and 6, and diminished later to lower values or zero. Intrinsic reading motivation decreased gradually by 0.289 SD, 0.215 SD, 0.085 SD, and 0.046 SD over consecutive waves. The variances for the change score variables were statistically significant, indicating interindividual differences in intraindividual change. Although the average trend was negative, the level of intrinsic motivation increased in some students. The initial level of intrinsic reading motivation correlated negatively with the changes, indicating that students who enjoyed reading more at the first measurement occasion decreased more over time.

Changes in intrinsic reading motivation, support for autonomy, relatedness, and competence between Grades 5 and 9. Note. Mean levels of each variable at a measurement occasion were calculated based on latent change score models estimated for each variable separately. The scales of the variables are not equated

Student perceptions of autonomy support, support for relatedness and competence had a different pattern of change compared to the change in intrinsic reading motivation. They decreased between Grades 5 and 6 (by 0.262 SD, 0.252 SD, and 0.261 SD, respectively), which was followed by a null (change between Grades 6 and 7) or very small (up to 0.05 SD) decline over the waves that followed. Again, the variances of all latent change score variables were statistically significant indicating that, in the case of a decrease, student perceptions improved over time in some students, or, in the case of null mean change, the change varied among students. The negative correlations between the changes and the initial levels of autonomy support, support for relatedness, and competence indicated that the higher the initial level of all three, the larger the decline. Table 3 contains information on the initial level, changes between consecutive waves, their variances, as well as correlations between the initial levels and changes in all four variables. Overall, the analyses confirmed our expectations.

Change–change relationships

The change–change model, presented in Table 4, had a good fit to the data (see Table 1). In the model, changes in student-perceived support for competence consistently predicted changes in intrinsic reading motivation. A decrease in perceived support for competence (or a lower latent change score in waves with null mean change) predicted a decrease in intrinsic reading motivation, with the strength of the relationship ranging from β = 0.072, SE = 0.023, p = .003 (change between Grades 6 and 7) to β = 0.096, SE = 0.021, p < .001 (change between Grades 8 and 9). Moreover, a decrease in perceived autonomy support in German lessons (or a lower latent change score in waves with null mean change) predicted a decrease in intrinsic reading motivation at three out of four occasions: between Grades 5 and 6 (β = 0.071, SE = 0.025, p = .01), 6 and 7 (β = 0.086, SE = 0.025, p = .005), and 7 and 8 (β = 0.064, SE = 0.020, p = .02). Meanwhile, changes in perceived support for relatedness in German lessons predicted changes in intrinsic reading motivation at two out of four occasions. A decrease in the former (or a lower latent change score in waves with null mean change) predicted a decrease in the latter between Grades 5 and 6 (β = 0.082, SE = 0.019, p < .001), 6 and 7 (β = 0.079, SE = 0.019, p = .003). Overall, changes in the predictors explained between 1.4% and 4.0% of the variance of changes in intrinsic reading motivation.

Discussion

This study verified whether changes in selected aspects of student-perceived teacher support for autonomy, relatedness, and competence predicted changes in intrinsic reading motivation, as postulated by Cognitive Evaluation Theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017, 2020). It also investigated whether teacher need-supportive behaviour and intrinsic reading motivation changed over the course of lower secondary school (Grade 5-Grade 9). The analyses revealed a decrease in all four constructs in the study, although the patterns of change were not uniform. Intrinsic reading motivation gradually decreased over the years whereas student-perceived teacher behaviour decreased between Grades 5 and 6 and was either stable or dropped slightly later. Moreover, changes in teacher support for competence consistently predicted changes in intrinsic reading motivation, whereas changes in support for autonomy and classroom interactions did so at three and two occasions out of four, respectively.

Changes over lower secondary school

As expected, the analyses revealed a decline in intrinsic reading motivation. However, although the trend was decreasing, the variability of the change score variables indicated that some students experienced increases. This suggests that decreases are not inevitable. As Cognitive Evaluation Theory posits (Ryan & Deci, 2017, 2020), it may be avoided by, among others, providing appropriate support for student needs, which was exactly what this study tested.

Previous studies have reported a similar declining trend in various motivational constructs, for example, academic self-concept, self-efficacy, learning goal orientations, or homework effort (e.g., Orth et al., 2021; Postigo et al., 2022; Trautwein et al., 2006). This suggests that the decline in intrinsic reading motivation is not an isolated phenomenon that occurs in only one aspect of student functioning, but a broader, potentially developmental, trend. The decreases might also share their roots.

Although perceived teacher need-supportive behaviour also declined overall, there was no average change between selected measurement occasions. Moreover, the students differed in the change in their perceptions as the change variables had significant variances. It means that for some students their perceptions not only not decreased but even increased, which implies that some teachers are able to provide a need-supportive learning environment as perceived by their students.

In the case of all measured constructs, the decreases were most pronounced between Grades 5 and 6, just after the transition to lower secondary school. The result is in line with past research indicating that transition periods are particularly difficult for students due to multiple changes that they involve, including changes in academic demands, learning environments, or social relationships (see Jindal-Snape et al., 2021).

Change–change relationships

In this study, changes in student-perceived support for competence consistently positively predicted changes in intrinsic motivation, whereas changes in perceived support for autonomy and relatedness did so in three and two occasions out of four, respectively. The results confirm therefore that student-perceived teacher behaviour in German lessons is related to intrinsic reading motivation despite the fact such lessons cover a lot more than reading-related instruction. To date, such relationships have been confirmed only in cross-sectional studies (e.g., De Naeghel et al., 2014; Haw & King, 2022). The links in this study may be explained in various ways. They may exist due to teachers expressing similar behaviour while teaching various skills (not only reading) or because need-supportive instruction in other skills in German lessons spills over on intrinsic motivation in reading.

It is, however, unclear why changes in perceived support for autonomy and relatedness did not predict changes in motivation between selected measurement occasions. Potentially, it is because the coefficients represent the link over and above the other predictors, which in turn were correlated. Such correlations are not a surprise since past research has revealed that students tend to perceive the classroom environment rather holistically and give correlated ratings to its various dimensions (e.g., Rohatgi & Scherer, 2020; Van Eck et al., 2017). Alternatively, some other aspects of teacher need-supportive behaviour, which were not included in the study, might have changed significantly between these occasions, shaping changes in intrinsic reading motivation. For example, pressure on achievement or social comparisons in the classroom may increase as students approach the next transition (after Grade 9), affecting their intrinsic reading motivation and resulting in weakened links of those aspects that do not change much.

A change in developmental needs may be yet another reason. According to Goldstein et al. (2015), early adolescents face an environment which is more competitive, performance-oriented, and structured. These challenges might endanger student self-efficacy in reading and result in an increased need for support for competence. In such a developmental transition, the perception of being given enough autonomy or the feeling of connection with the others in the classroom might become less important than perceived support for competence. Since low teacher expectations may hamper student belief in themselves and lead to decreased intrinsic motivation (Hornstra et al., 2018), in older grades, their perception may become more important for shaping the decrease in intrinsic motivation than the perception of the other teacher need-supportive behaviours.

At the same time, the partial overlap between predictors and outcomes in this study may be a potential reason why changes in perceived teacher behaviour explained 1.4% to 4% of the variance of changes in intrinsic reading motivation, which represents a small effect. Such effects, however, are very common in behavioural sciences (Cohen, 2013). Moreover, German lessons do not focus solely on reading but cover, among others, spelling, grammar, and writing. Furthermore, in older grades, reading instruction focuses more on the interpretation of various types of texts, while reading itself, although required, becomes an out-of-school activity. Additionally, we measured only selected aspects of perceived need-supportive behaviour, which could also contribute to rather low explained variances. For the above mentioned reasons, it is probable that in this study the amount of explained variance in changes in intrinsic reading motivation is underestimated. Furthermore, since reading is crucial for learning in many subjects (Snow & Biancarosa, 2003) and occurs also outside of school, other formal, non-formal and informal learning environments, for example, the home learning environment or the classroom environments in other subjects, may also play a role. Such links between the home learning environment and intrinsic motivation have been confirmed in the past (see e.g., Gonzalez-DeHass et al., 2005 for a review). Moreover, Cognitive Evaluation Theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017, 2020) proposes that internal factors (e.g., ego involvement) affect intrinsic motivation, and they were not investigated in this study.

Limitations and future research directions

While interpreting the results of this study, several limitations should be taken into account. First, the study included only selected aspects of support for autonomy, relatedness, and competence, which could contribute to rather low explained variances. Including other aspects of the three, for example, teacher-student relationship or the provision of rationales for pursued learning activities would allow a stronger test of the expected relationships. Future studies should include more comprehensive measures of need-supportive teacher behaviour.

Second, although we used a large nationwide sample, it was not representative due to significant missingness and attrition (see also Zinn et al., 2020). Missing values were present, among others, on variables representing SES, which makes the assessment of how much the sample deviates from representativeness even more difficult. However, the high share of children attending an academic track school and the high average value of ISEI suggest that low-SES students were underrepresented in the sample. This, in turn, might bias the results. However, to reduce bias, we included various correlates of missingness in the analyses, for example, SES-related variables and past achievement. Nevertheless, future studies should improve participation rates.

Third, we used self-reports, which might have increased the amount of shared variance and led to the overestimation of regression coefficients. Additionally, although the data were nested, we were unable to account for nesting due to the lack of longitudinal class identifiers. Future studies should use data that either allow accounting for clustering or are not nested at all. Finally, this study, although longitudinal, cannot give a definite answer if the studied relationships are causal.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to verify longitudinal links between student-perceived teacher behaviour in lessons in the language of instruction and intrinsic reading motivation. It provides further support for the usefulness of Cognitive Evaluation Theory in explaining student motivation. Moreover, it suggests that creating the classroom learning environment that is supportive of student needs may help prevent the decline in intrinsic reading motivation. Since teacher behaviour is malleable, it could be addressed in teacher-targeted interventions or become an element of teacher training.

However, since changes in need-supportive behaviour did not explain much variation in changes in intrinsic reading motivation, targeting such behaviour cannot be considered an ultimate solution. Future studies could investigate similar longitudinal links between the home learning environment or parental involvement in education and intrinsic reading motivation.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (https://www.neps-data.de/Data-Center/Data-Access). Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which is the reason why they cannot be provided by the authors of the study. Survey questionnaires are available on the NEPS study website (https://www.neps-data.de/Data-Center/Data-and-Documentation). Analysis code is available in the online supplement and by emailing the corresponding author.

Change history

21 December 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-023-10505-4

References

Aßmann, C., Steinhauer, H. W., Würbach, A., Zinn, S., Hammon, A., Kiesl, H., Rohwer, G., Rässler, S., & Blossfeld, H.-P. (2019). Sampling designs of the National Educational Panel Study: Setup and panel development. In H.-P. Blossfeld & H.-G. Roßbach (Eds.), Education as a lifelong process (pp. 35–55). Springer VS.

Becker, M., McElvany, N., & Kortenbruck, M. (2010). Intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation as predictors of reading literacy: A longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(4), 773–785. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020084

Berry, D., & Willoughby, M. T. (2016). On the practical interpretability of cross-lagged panel models: Rethinking a developmental workhorse. Child Development, 88(4), 1186–1206. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12660

Blossfeld, H.-P., & Roßbach, H.-G. (Eds.). (2019). Education as a lifelong process: The German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS). Edition ZfE (2nd ed.). Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-23162-0

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (6th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 793–828). Wiley.

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Elsevier Science & Technology.

De Naeghel, J., Valcke, M., De Meyer, I., Warlop, N., van Braak, J., & Van Keer, H. (2014). The role of teacher behavior in adolescents’ intrinsic reading motivation. Reading and Writing, 27(9), 1547–1565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-014-9506-3

Eccles, J., Midgley, C., Wigfield, A., Buchanan, C. M., Reuman, D., Flanagan, C., & Mac Iver, D. (1993). Development during adolescence: The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and in families. American Psychologist, 48(2), 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.48.2.90

Enders, C. K. (2010). Applied missing data analysis. Guilford Press.

Fauth, B., Göllner, R., Lenske, G., Praetorius, A.-K., & Wagner, W. (2020). Who sees what? Conceptual considerations on the measurement of teaching quality from different perspectives. Zeitschrift Für Pädagogik, 66(1), 138–155. https://doi.org/10.3262/ZPB2001138

Ganzeboom, H., De Graaf, P., & Treiman, D. (1992). A standard international socio-economic index of occupational status. Social Science Research, 21(1), 1–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/0049-089X(92)90017-B

Geiser, C. (2013). Data analysis with Mplus. The Guilford Press.

Gentry, M., Gable, R. K., & Rizza, M. G. (2002). Students’ perceptions of classroom activities: Are there grade-level and gender differences? Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(3), 539–544. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.3.539

Gnambs, T., & Hanfstingl, B. (2016). The decline of academic motivation during adolescence: An accelerated longitudinal cohort analysis on the effect of psychological need satisfaction. Educational Psychology, 36(9), 1691–1705. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2015.1113236

Goldstein, S. E., Boxer, P., & Rudolph, E. (2015). Middle school transition stress: Links with academic performance, motivation, and school experiences. Contemporary School Psychology, 19(1), 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-014-0044-4

Gonzalez-DeHass, A. R., Willems, P. P., & Holbein, M. F. D. (2005). Examining the relationship between parental involvement and student motivation. Educational Psychology Review, 17(2), 99–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-005-3949-7

Guthrie, J. T., & Wigfield, A. (2017). Literacy Engagement and Motivation: Rationale, research, teaching, and assessment. In D. Lapp & D. Fisher (Eds.), Handbook of research on teaching the english language arts (4th ed., pp. 57–84). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315650555-3

Hardre, P. L., & Reeve, J. (2003). A motivational model of rural students’ intentions to persist in, versus drop out of, high school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(2), 347–356. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.2.347

Haw, J. Y., & King, R. B. (2022). Need-supportive teaching is associated with reading achievement via intrinsic motivation across eight cultures. Learning and Individual Differences, 97, 102161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2022.102161

Hornstra, L., Stroet, K., van Eijden, E., Goudsblom, J., & Roskamp, C. (2018). Teacher expectation effects on need-supportive teaching, student motivation, and engagement: A self-determination perspective. Educational Research and Evaluation, 24(3–5), 324–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611.2018.1550841

Howard, J. L., Bureau, J., Guay, F., Chong, J. X. Y., & Ryan, R. M. (2021). Student motivation and associated outcomes: A meta-analysis from Self-Determination Theory. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(6), 1300–1323. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620966789

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Jindal-Snape, D., Symonds, J. E., Hannah, E. F. S., & Barlow, W. (2021). Conceptualising primary-secondary school transitions: A systematic mapping review of worldviews, theories and frameworks. Frontiers in Education, 6, 540027. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.540027

Klein, K. J., Bliese, P. D., Kozolowski, S. W. J., Dansereau, F., Gavin, M. B., Griffin, M. A., Hofmann, D. A., James, L. R., Yammarino, F. J., & Bligh, M. C. (2000). Multilevel analytical techniques: Commonalities, differences, and continuing questions. In K. J. Klein & S. W. J. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions, and new directions (pp. 512–553). Jossey-Bass/Wiley.

Lazarides, R., Fauth, B., Gaspard, H., & Göllner, R. (2021). Teacher self-efficacy and enthusiasm: Relations to changes in student-perceived teaching quality at the beginning of secondary education. Learning and Instruction, 73, 101435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2020.101435

Lüdtke, O., Marsh, H. W., Robitzsch, A., & Trautwein, U. (2011). A 2 × 2 taxonomy of multilevel latent contextual models: Accuracy–bias trade-offs in full and partial error correction models. Psychological Methods, 16(4), 444–467. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024376

Marsh, H. W., Pekrun, R., & Lüdtke, O. (2022). Directional ordering of self-concept, school grades, and standardized tests over five years: New tripartite models juxtaposing within- and between-person perspectives. Educational Psychology Review, 34, 2697–2744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-022-09662-9

Maulana, R., Opdenakker, M.-C., & Bosker, R. (2016). Teachers’ instructional behaviors as important predictors of academic motivation: Changes and links across the school year. Learning and Individual Differences, 50, 147–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.07.019

Miyamoto, A., Murayama, K., & Lechner, C. M. (2020). The developmental trajectory of intrinsic reading motivation: Measurement invariance, group variations, and implications for reading proficiency. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 63, 101921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101921

Möller, J., & Bonerad, E.-M. (2007). Fragebogen zur habituellen Lesemotivation [Habitual Reading Motivation Questionnaire]. Psychologie in Erziehung Und Unterricht, 54(4), 259–267.

Muthén, B., Muthén, L., & Asparouhov, T. (2016). Regression and mediation analysis using Mplus. Muthén & Muthén.

Network, N. E. P. S. (2022). National Educational Panel Study, Scientific Use File of Starting Cohort Grade 5. Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi). https://doi.org/10.5157/NEPS:SC3:12.0.0

Orth, U., Dapp, L. C., Erol, R. Y., Krauss, S., & Luciano, E. C. (2021). Development of domain-specific self-evaluations: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120(1), 145–172. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000378

Postigo, Á., Fernández-Alonso, R., Fonseca-Pedrero, E., González-Nuevo, C., & Muñiz, J. (2022). Academic self-concept dramatically declines in secondary school: Personal and contextual determinants. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 3010. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19053010

Rohatgi, A., & Scherer, R. (2020). Identifying profiles of students’ school climate perceptions using PISA 2015 data. Large-Scale Assessments in Education, 8, 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40536-020-00083-0

Ryan, A. M., & Patrick, H. (2001). The classroom social environment and changes in adolescents’ motivation and engagement during middle school. American Educational Research Journal, 38(2), 437–460. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312038002437

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. The Guilford Press.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

Schaffner, E., Schiefele, U., & Ulferts, H. (2013). Reading amount as a mediator of the effects of intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation on reading comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly, 48(4), 369–385. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.52

Scheerens, J. (2016). Educational effectiveness and ineffectiveness. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-7459-8

Scherrer, V., & Preckel, F. (2019). Development of motivational variables and self-esteem during the school career: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Review of Educational Research, 89(2), 211–258. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654318819127

Skopek, J., Pink, S., & Bela, D. (2012). Data manual: Starting Cohort 3—From lower to upper secondary school. NEPS SC3 1.0.0 (NEPS Research Data Paper). University of Bamberg.

Snow, C. E., & Biancarosa, G. (2003). Adolescent literacy and the achievement gap: What do we know and where do we go from here? Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Steyer, R., Partchev, I., & Shanahan, M. (2000). Modeling true intraindividual change in structural equation models: The case of poverty and children’s psychosocial adjustment. In T. D. Little, K. U. Schnabel, & J. Baumert (Eds.), Modeling longitudinal and multilevel data: Practical issues, applied approaches, and specific examples (pp. 103–119). Erlbaum. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410601940-10

Toste, J. R., Didion, L., Peng, P., Filderman, M. J., & McClelland, A. M. (2020). A meta-analytic review of the relations between motivation and reading achievement for K–12 students. Review of Educational Research, 90(3), 420–456. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654320919352

Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Kastens, C., & Köller, O. (2006). Effort on homework in grades 5–9: Development, motivational antecedents, and the association with effort on classwork. Child Development, 77(4), 1094–1111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00921.x

Van Eck, K., Johnson, S. R., Bettencourt, A., & Johnson, S. L. (2017). How school climate relates to chronic absence: A multi–level latent profile analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 61, 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2016.10.001

Wagner, W., Helmke, A., & Rösner, E. (Eds.). (2009). Deutsch Englisch Schülerleistungen International. Dokumentation der Erhebungsinstrumente für Schülerinnen und Schüler, Eltern und Lehrkräfte [German English Student Achievement International. Documentation of survey instruments for students, parents and teachers]. GFPF. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:3252

Way, N., Reddy, R., & Rhodes, J. (2007). Students’ perceptions of school climate during the middle school years: Associations with trajectories of psychological and behavioral adjustment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 40(3–4), 194–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-007-9143-y

You, S., Dang, M., & Lim, S. A. (2016). Effects of student perceptions of teachers’ motivational behavior on reading, English, and mathematics achievement: The mediating role of domain specific self-efficacy and intrinsic motivation. Child & Youth Care Forum, 45(2), 221–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-015-9326-x

Zinn, S., Würbach, A., Steinhauer, H., & Hammon, A. (2020). Attrition and selectivity of the NEPS starting cohorts: An overview of the past 8 years. AStA Wirtschafts- Und Sozialstatistisches Archiv, 14(2), 163–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11943-020-00268-7

Acknowledgements

This paper uses data from the National Educational Panel Study (NEPS; see Blossfeld & Roßbach, 2019). The NEPS is carried out by the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi, Germany) in cooperation with a nationwide network.

Funding

Anna Hawrot’s work on the paper was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) grant 470282638 awarded to Ilka Wolter. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: AH, JZ; Data curation: AH; Formal analysis: AH; Methodology: AH; Writing—original draft: AH; Writing—review & editing: AH, JZ.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethics approval

The NEPS study is conducted under the supervision of the German Federal Commissioner for Data Protection and Freedom of Information (BfDI) and in coordination with the German Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs (KMK) and—in the case of surveys at schools—the Educational Ministries of the respective Federal States. All data collection procedures, instruments, and documents were checked by the data protection unit of the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi). The necessary steps are taken to protect participants’ confidentiality according to national and international regulations of data security. All participants of age and legal guardians of underage participants provided written informed consent prior to study enrolment. All participants could withdraw from the study at any time. All the analyses are secondary analyses of data published previously.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: In the original publication of this article, in the subsection, “Changes in perceived teacher behaviour and intrinsic reading motivation”, there were couple of errors in two sentences.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hawrot, A., Zhou, J. Do changes in perceived teacher behaviour predict changes in intrinsic reading motivation? A five-wave analysis in German lower secondary school students. Read Writ (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-023-10472-w

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-023-10472-w