Abstract

Stereotype threat (ST) is a potential explanation for inequalities in language competencies observed between students from different language backgrounds. Language competencies are an important prerequisite for educational success, wherefore the significance for investigation arises. While ST effects on achievement are empirically well documented, little is known about whether ST also impairs learning. Thus, we investigated vocabulary learning in language minority elementary school students, also searching for potential moderators. In a pre-post design, 240 fourth-grade students in Germany who were on average 10 years old (MAge = 9.92, SD = 0.64; 49.8% female) were randomly assigned to one of four experimental conditions: implicit ST, explicit ST without threat removal before posttest, explicit ST with threat removal before posttest, and a control group. Results showed that learning difficult vocabulary from reading two narrative texts was unaffected by ST. Neither students’ identification with their culture of residence and culture of origin nor stereotyped domain of reading were moderators. The findings are discussed with regard to content and methodological aspects such that a motivation effect might have undermined a possible ST effect. Implications for future research include examining the question at what age children become susceptible to ST and whether students have internalized negative stereotypes about their own group, which could increase the likelihood of ST effects occurring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years, cultural and linguistic diversity of students and thus of school classes has increased worldwide (OECD, 2019). Large-scale assessments such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) for high schools and the Progress in International Reading Literacy (PIRLS) for elementary schools have repeatedly shown that there are on average differences in achievement in various domains between language minority and language majority children (Mullis et al., 2017; OECD, 2019). Several reasons for these disparities are discussed and investigated. In addition to differences in socioeconomic status, psychological processes concerning stereotypes and stereotype threat (ST) have proven to partly explain achievement differences between immigrant and non-immigrant students (e.g., Appel et al., 2015; Steele & Aronson, 1995). ST describes the situation in which knowledge of a negative stereotype about a group to which one belongs triggers the threat to confirm this stereotype oneself (Steele & Aronson, 1995). ST impairs achievement, thus contributing to a confirmation of the negative stereotype (Baysu & Phalet, 2019; Steele & Aronson, 1995). In achievement situations, ST is empirically well-researched (Appel & Kronberger, 2012; Flore & Wicherts, 2015), but less is known about whether ST also impairs learning, such as the acquisition of new vocabulary (Rydell & Boucher, 2017). First empirical findings suggest that vocabulary growth can be negatively influenced by ST as early as in elementary school (Sander et al., 2018). This is particularly worrisome, as elementary school years are of crucial importance for further educational pathways, and a strong command of the language of instruction is a prerequisite for future educational success (e.g., Biemiller, 2005).

Numerous studies have shown that various variables, for example, the identification with the culture of residence and culture of origin as well as identification with a particular academic domain, can mitigate or enhance ST effects in achievement situations (e.g., Baysu & Phalet, 2019; Pansu et al., 2016). However, it is unclear whether these variables moderate ST effects in learning situations. Thus, we examine potential effects and possible moderators of ST in a vocabulary learning situation among language minority elementary school students.

Theoretical framework

Importance of vocabulary

Vocabulary, as the entirety of words in the mental lexicon, is a prerequisite for reading, listening, and understanding spoken and written language and is therefore highly relevant for both academic success and later professional success (e.g., Graves, 2016). Elementary school years are of particular importance for vocabulary acquisition and promotion, as children learn an average of 1,000 new words per year during this period (e.g., Biemiller, 2005). Strategies promoting vocabulary can be distinguished according to the kind of instruction, either implicit (e.g., reading texts; McElvany & Artelt, 2007; Vidal, 2011; Webb, 2008) or explicit (e.g., vocabulary learning; Elgort, 2011; Nation, 2013). Implicit instruction focuses on the meaning aspect of language, whereas explicit instruction aims to systematic teach grammar and vocabulary (DeKeyser, 2003; Ellis et al., 2009). There is evidence that combining both is effective for vocabulary acquisition (Karami & Bowles, 2019; Marulis & Neuman, 2010; Stanat et al., 2012). McElvany et al. (2017) revealed with regard to vocabulary acquisition among language minority children that learning from context (reading a German-language text with target words that can be deduced from the context of the text) was effective compared to a control group (reading a German-language text without target words).

Alongside differences in achievement in general, differences in vocabulary in particular also exist to the detriment of language minority children compared to native children despite similar cognitive abilities (Europe: Bosman & Janssen, 2017; Novita et al., (2021); America/Australia/UK: Bialystok et al., 2010; Calvo & Bialystok, 2014; Hoff, 2018; Washbrook et al., 2012). These differences can be attributed in some part to ST (e.g., Sander et al., 2018; Froehlich et al., 2018; Steele & Aronson, 1995). Referring to language minority children, achievement-related stereotypes do exist (Froehlich et al., 2016).

The phenomenon of stereotype threat

Stereotypes generally refer to beliefs about the characteristics and attributes of a group and its members (Dovidio et al., 2010). Between the ages of two and five, children begin to evolve stereotypes, for example, related to gender (Martin & Ruble, 2010). Cognitive abilities and conceptual understanding continue to develop with age such that categorization processes leading to stereotypes are no longer based solely on perceptual differences but also on internal, abstract attributes (Baron & Banaji, 2006; Bar-Tal, 1996; Kite & Whitley, 2016). Stereotypes can be activated automatically and unconsciously and thus can influence the perception of groups and their members as well as the behavior displayed towards them (Dovidio et al., 2010). Research on ST originated in the USA with the seminal investigations by Steele & Aronson (1995), who focused on lower achievement outcomes under ST among ethnic minorities on standardized tests. In their fourth experiment, the authors showed that when Black American undergraduates were asked about their ethnicity before solving difficult verbal ability items, they performed worse on those items compared to White American undergraduates (Steele & Aronson, 1995). Their studies led to extensive research on this phenomenon (e.g., Appel et al., 2015; Nadler & Clark, 2011; Nguyen & Ryan, 2008). With respect to students of Turkish origin, Martiny et al. (2014) found for ninth-graders that students of Turkish origin who were threatened scored lower than natives and also scored lower compared to students of Turkish origin in the control condition.

Activation of stereotype threat

A more differentiated picture of ST emerges when a distinction is made regarding the explicitness of the threat activation. An implicit threat is given, for example, by having research participants indicate their ethnicity via their country of birth and family language, without giving a direct cue about their group’s disadvantaged position (Sander et al., 2018; Shewach et al., 2019). Ambady et al. (2001) administered ST implicitly by presenting a short questionnaire to children in grades 3 to 8, including questions about the language spoken at home, before they took a math test. The results indicated that the subtle activation of negative stereotypes impaired Asian American girls’ achievement but not Asian American boys’ achievement.

Explicit threat is administered by directly referring to achievement differences between groups (e.g., Keller & Dauenheimer, 2003). Also, Sander et al. (2018) explicitly activated ST by pointing out to their participants that those who (even sometimes) speak a language other than German at home face problems learning new unknown vocabulary. Nguyen & Ryan (2008) distinguished in their meta-analysis implicit and explicit activation, with the latter additionally differentiated into moderately explicit (direct evidence of group differences) and blatantly explicit (direct evidence that one group outperformed the other group). For minorities, they found that a moderately explicit threat led to larger ST effects compared to blatant activation, and this in turn led to larger effects than implicit activation (d = 0.64 vs. d = 0.41 vs. d = 0.22). Similarly, Appel et al. (2015) revealed that while all three forms of activation led to achievement deficits, moderately explicit activation yielded the largest effect for people with immigrant background.

Numerous studies examined ST in achievement situations, which is empirically well-established (e.g., Appel et al., 2015; Spencer et al., 2016). Here, an implicitly or explicitly activated ST impairs access to or application of knowledge or skills the person has previously acquired (Appel et al., 2015; Nguyen & Ryan, 2008; Steele & Aronson, 1995). Little is known about whether ST also affects the ability to gain knowledge in a learning context (Rydell & Boucher, 2017; Taylor & Walton, 2011). In our research, we had children work on a language vocabulary learning task while being exposed to different forms of ST. Whereas most studies have investigated ST effects on achievement in mathematics or sciences (e.g., Flore & Wicherts, 2015; Neuville & Croizet, 2007), we focused on the less researched domain of language competency, which is of particular importance to a group especially vulnerable to ST: language minority children.

Stereotype threat and learning

In a learning situation, individuals acquire new knowledge and skills by processing new information and building a coherent representation in long-term memory (McDaniel et al., 2014). In achievement situations, ST can impair the efficiency of working memory (Schmader et al., 2008), while Boucher et al. (2012) assumed that ST in learning situations interferes with encoding the content from the learning phase. The authors suggested that ST can be examined in a learning situation by comparing a condition in which the threat is removed before the achievement situation to a condition in which the threat is not removed (Boucher et al., 2012).

One study separating learning and achievement situations was by Boucher et al. (2012). The authors found that female undergraduates in mathematics revealed lower learning outcomes in a ST condition and in a condition with ST removal after the learning phase compared, respectively, to a control group and a condition where the threat was removed before the learning phase. Furthermore, a study by McLaughlin Lyons et al. (2018) showed for a sample of fifth-grade students from different ethnic minority groups that in a videotaped challenging mathematics lesson, students in the ST condition had lower learning growth compared to the control group. Taylor & Walton (2011) also investigated ST in a learning situation and focused on vocabulary learning of difficult and seldom words among African American university students. Students who had to learn under ST remembered fewer words after a time interval of 1 to 2 weeks than students who had not learned under threat. Sander et al. (2018) examined ST in a vocabulary learning situation among 118 language minority elementary school children in Germany. In a pre-post design, the children were assigned to one of three experimental ST conditions (implicit, explicit, and control). The threat was administered before the learning situation, in which the children had to learn difficult words from narrative texts. Afterwards, they completed a vocabulary posttest. The results indicated that vocabulary growth was lower in both ST conditions compared to the control condition, indicating that a ST effect occurred in learning situations. However, due to the design, with no removal of the threat before the posttest, the findings cannot solely be attributed to the threat affecting the learning situation. Thus, it remains unclear whether ST had an effect on the learning or achievement situation, as it is also possible that children were less able to retrieve their knowledge in the posttest due to the threat. To sum up, first, studies indicate that in addition to achievement, learning can also be influenced by ST.

Person-related moderators of stereotype threat

Various variables may decrease or increase ST vulnerability (e.g., Appel et al., 2015; Steele, 1997). ST research provides broad findings on facilitators that can mitigate or enhance ST impacts (Pennington et al., 2016; Spencer et al., 2016). Additionally to situational factors, personal factors are of high importance which include, for example, group and domain identification (Steele et al., 2002). Therefore, we focused on identification with the culture of residence and culture of origin as well as identification with the domain of reading.

Ethnic identity begins to develop during middle childhood. Individuals with an immigrant background can develop both an identity as a member of their culture of origin and one as a member of their culture of residence (Zander & Hannover, 2013; Berry et al., 2006; Ruble et al., 2004). Identification with the culture of residence and origin can be important personal factors related to ST (Baysu & Phalet, 2019; Weber et al., 2015). According to social identity theory (SIT) (Tajfel & Turner, 1986), individuals strive for a positive social identity based on comparison processes with social groups. Therefore, it can be assumed that individuals may be affected by ST when they identify highly with a stereotyped group. For example, Weber et al. (2015) examined both identification with the culture of origin and the culture of residence in a sample of eighth-graders with an immigrant background in Austria. Students under explicit threat exhibited better cognitive achievement when they identified highly with Austria (culture of residence), independently of their identification with their culture of origin. In contrast, students’ achievement in the control condition and in the implicit threat condition was unrelated to identification with Austria. Furthermore, two studies by Baysu & Phalet (2019) with Turkish origin and Moroccan origin minority students in Belgian secondary schools revealed that a dual identity can either promote or hinder minority achievement depending on stereotype threat experienced during a verbal test. In low threat situations, dual-identity students showed higher achievement and higher self-esteem than otherwise-identified students in the control condition. In high threat situations, dual-identity students performed worse and reported more anxiety compared to the control condition. In their meta-analysis, Nguyen & Benet-Martínez (2013) found, when focusing on people between 10 and 70 years, a strong and positive association between individuals having dual identities and their psychological and sociocultural adjustment compared to individuals who identified with only one of the two cultures. In a study by Armenta (2010), however, the relevance of identification with the culture of origin in a sample of undergraduate students was shown. High ethnic identification led to weaker achievement in the presence of negative achievement stereotypes (Latinos) and to stronger achievement in the presence of positive achievement stereotypes (Asian Americans). In contrast, lower ethnic identification did not have an effect regardless of the achievement stereotype activated. Similarly, Cole et al. (2007) reported that ethnic minority students who identified highly with their culture of origin were more vulnerable to ST. Concerning vocabulary learning situations, Sander et al. (2018) examined fourth-graders’ ethnic identification using a single undifferentiated, nominally scaled item and found no moderation of the ST effect. Overall, empirical findings concerning identification with the culture of residence and origin are heterogeneous.

Another important personal factor is identification with the stereotyped domain. According to Steele’s (1997) conceptualization, it is composed of the value and importance a person attributes to that domain and of the abilities one believes one has in that domain. It is assumed that high identification with the stereotyped domain will increase the pressure not to confirm the stereotype in that domain (Wasserberg, 2017). The results of the second experiment by Aronson et al. (1999) revealed that high identifiers (Asian students from university) performed less well in the threat than in the non-threat condition. Keller (2007) investigated identification with the domain of mathematics among tenth-grade students in Germany. Girls who identified highly with the domain of math had a loss of achievement in an ST condition compared to girls who identified less with that domain. With regard to the domain of reading, Pansu et al. (2016) showed in a sample of 80 French third-graders highly identified with the domain of reading that boys scored lower than girls on a reading test in a threat condition. The opposite was found in the reduced threat condition: Here, boys scored higher than girls.

In summary, we assumed that regarding the identification with the culture of residence, a high identification might lead to a weaker ST effect, because the threat might affect those students less given that identity could serve as a buffer. With respect to the identification with the culture of origin and the identification with the domain of reading, we expected those to enhance the ST effect because high identification with the culture of origin may increase sensitivity to negative stereotypes towards this group and high domain identification should generally increase the effect of threat (Steele et al., 2002) due to personal concernedness or importance. Both should correspondingly result in lower vocabulary growth.

Research questions

ST is a possible explanation for achievement differences based on ethnicity (e.g., Froehlich et al., 2018). Less is known with regard to ST effects in learning situations (Rydell & Boucher, 2017). Due to the fact that disparities also exist in language competencies such as vocabulary and that vocabulary is of high importance for school and professional success, we focused on the effects of ST in vocabulary learning situations. Sander et al. (2018) revealed that ST impaired vocabulary learning, although it remained unclear whether the ST effect occurred in an achievement or a learning situation. Thus, we wanted to replicate and broaden these findings by Sander et al. (2018) with a larger sample size and an extended study design. Furthermore, we operationalized identification with the culture of origin in a more differentiated manner and included two other potential moderators in order to obtain a more fine-grained picture. We addressed the following research questions:

-

1.

Do language minority children exhibit lower growth in vocabulary in the presence of (a) implicit and/or (b) explicit ST without removal of the threat before posttest (hereinafter known as explicit without removal) relative to a condition without ST?

For both ST conditions we expected that language minority students will learn on average fewer words than students in the control condition (1a). Also, the extent of the ST effect should be larger in the explicit condition compared to the implicit condition (1b).

-

2.

Do language minority students differ in their vocabulary learning in the explicit ST condition with removal of the threat before posttest (hereinafter known as explicit with removal) and without removal?

As this was testing if ST is indeed effecting the learning rather than the achievement situation, we assumed that vocabulary growth would be similar in both conditions (2).

-

3.

To what extent is the expected ST effect on vocabulary growth moderated by (a) identification with the culture of residence and (b) origin and/or (c) identification with the stereotyped domain of reading?

-

We expected that the ST effect would be lower for language minority children who highly identified with the culture of residence, indicated by greater vocabulary growth compared to children who identified more weakly with the culture of residence (3a). For language minority students who highly identified with the culture of origin, we assumed that the ST effect would be larger, resulting in lower vocabulary growth (3b). Furthermore, we expected a larger ST effect for language minority children who highly identified with the reading domain and thus lower vocabulary growth compared to children who identified more weakly with the domain of reading (3c).

Method

Participants

Data for this study was collected in spring 2019 in the context of the project Effects and moderators of stereotype threat in vocabulary learning situations among students with immigrant background in elementary and secondary schools (ST2). A total of 822 elementary school students from 46 fourth-grade classes in 30 schools in North Rhine-Westphalia participated. Language majority students, children with special educational needs, and one child with implausibly high gains (maximum + 3 SD) between pre- and posttest were excluded from the sample. Therefore, the analyses were based on n = 240 language minority students (49.8% female) drawn from all 46 classes, who were just under 10 years old on average (M = 9.92, SD = 0.64). As the study focused on ST in the context of vocabulary acquisition, language minority status was operationalized based on family language (“I sometimes speak German at home and most of the time another language: ___________”/ “I never speak German at home, but I speak _________.”). There were no statistically significant differences between the four experimental conditions in sex, age, cognitive abilities, and amount of books at home as indicator of socioeconomic status (see Table A, Supplement 1).

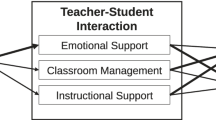

Experimental design and procedure

In order to test the impact of different ST conditions, a pre-post design was used (see Fig. 1). Prior to data collection, students were randomly assigned to one of four conditions: (a) implicit, (b) explicit without removal, (c) explicit with removal, and (d) control group. Each child got a tablet on which the experimental procedure was implemented and on which they entered their answers. We used the open source software OpenSesame (Mathôt et al., 2012) to program the experiment. The study was carried out by trained research assistants who used a standardized test manual. Participation was voluntary. Declaration of consent was given by parents before data collection.

Data collection lasted for two consecutive 45-min lessons. In the first lesson, children were asked how strongly they identified with the domain of reading and worked on a vocabulary pretest to assess their vocabulary with regard to the texts they would have to read in the subsequent learning units (see section “Instruments”). After pretest, the experimental manipulation was administered. Students in the implicit threat condition answered questions about their language spoken at home and both their and their parents’ country of birth. Students in the explicit threat condition read a short text and were informed that children who speak a language other than German at home have difficulties learning new words. The explicit condition with removal was configured following Boucher et al. (2012). Here, the threat was the same as in the explicit condition without removal, but students were informed before the last posttest that irrespective of which languages they speak at home, all children can learn equally well. Children in the control group did not receive any kind of threat. They answered questions concerning their favorite drink and meal. Following Nguyen and Ryan (2008), the implicit induction of threat can be classified as subtle and the explicit induction as blatant obvious. Each experimental condition was followed by two learning units with a corresponding vocabulary posttest (see Fig. 1). In each learning unit, students read a narrative text containing target words (see section “Instruments”). The meaning of the target words could be deduced from the text context. After reading these texts, children answered two multiple-choice questions to ensure that they had read the texts carefully. Additionally to the implicit learning task, an explicit learning element was added: students worked on a synonym game in which they had to assign synonyms from a list (not the same synonyms as in the vocabulary test) to the target words from the text. Subsequently, the correct solution to the synonym game was presented to every student. The posttest followed the synonym game, except for the explicit condition with removal. Here, the threat was removed before the children completed the last posttest. After a short break, students completed a second lesson. They worked on a cognitive ability test and answered questions regarding social demographics as well as their identification with the culture of residence and origin. Lastly, students in the implicit, explicit without removal, and control condition were also informed that all children can learn difficult words equally well, regardless of whether they speak a language other than German at home.

Instruments

Vocabulary test

The vocabulary pre- and posttest consisted of 18 target words and three icebreaker items to provide a positive beginning to the vocabulary test (McElvany et al., 2017). For each target word (e.g., “trivial”), a corresponding synonym had to be selected, which was presented together with four distractors (e.g., “triple/dry/sad/simple/wet”). Answers in the pre- and posttest were dichotomously coded (0 = incorrect or not completed; 1 = correct). Thus, children could achieve between 0 and 18 points. The pre- and posttest’s reliability was satisfactory.

Learning material

Each text in the learning unit was age-appropriate and encompassed about 300 words with nine target words (three nouns, three verbs, and three adjectives). Both learning texts were selected from the intervention study Potential of the native language to reduce educational inequality—Vocabulary acquisition before central transitions of the education system (InterMut) and have proven to produce good learning growth rates (cf. McElvany et al., 2017). The texts were about a detective story about a missing elephant in a zoo and about a child who suffers a mishap at home.

Sociodemographic data

In addition to age and gender (0 = boy; 1 = girl), family language as well as child and his/her parents’ country of birth (0 = Germany; 1 = other) were assessed. Students also indicated the number of books at home (Wendt et al., 2016). Five answers could be selected: from 1 = none or very few (0–10 books) to 5 = enough to fill three or more shelves (200 books).

Moderators of stereotype threat

Students’ identification with the culture of residence (Germany) was measured with items from the affective dimension of the scale for identification with Germany (Zander & Hannover, 2013). The six items were adapted to make them easier to understand for fourth-graders (e.g., “I have a good feeling when I think about Germany”). The scale provided information about the extent to which students identify with Germany. Furthermore, the children answered six items regarding identification with their culture of origin. The scale covered how strongly they feel connected to their own or their parents’ country of origin (e.g., “I feel strongly connected with this country and this culture”). These items were also adapted from the original items by Zander & Hannover (2013). In order to capture identification with the reading domain, items by Keller (2007) and Arens et al. (2011) were modified. The scale consisted of four items and indicated how much learners identify with this particular academic domain (e.g., “It is important to me that I am good at reading”). All items were measured on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). Table 1 contains scale characteristics. For subsequent analyses, we dichotomized all three variables using a median split (0 = low identification, 1 = high identification).

Cognitive abilities

The figural subtest of the standardized German cognitive ability test for grades 4 to 12 (Kognitiver Fähigkeitstest [KFT] 4–12 R; Heller & Perleth, 2000) was used to measure cognitive abilities. Following ST theory, cognitive abilities were included as an important control variable because the theory postulates that effects of ST are found despite similar cognitive abilities. In addition, given the background of a language-based ST, a figural, language-free subtest was explicitly chosen to examine cognitive abilities independent of linguistic abilities. The test consists of 25 items, which were dichotomously coded (0 = incorrect or incomplete; 1 = correct). Between 0 and 25 points could be achieved. The children were shown two objects that have a certain relation to each other (e.g., little black circle to large white circle). They were then shown other objects (e.g., little black triangle) and had to select the appropriate analogue object (e.g., large white triangle) from five objects.

Statistical analyses

SPSS 27 was used for descriptive statistics and statistical analyses. An a priori sensitivity analysis with G*Power revealed that n = 44 participants were required for each of the four conditions (N = 176) (Faul et al., 2007). Results were considered statistically significant if the p-value was ≤ 0.05. As effect size measures, partial eta square and Cohen’s d were reported (Cohen, 1988). Statistical power was calculated a posteriori using G*Power (Faul et al., 2007). The posttest consisted of 18 words and was composed of the nine words from both posttests 1 and 2. In order to investigate ST’s impairment of vocabulary growth in research question 1, we calculated a repeated measures ANOVA with planned contrasts. The within-subject variable was the vocabulary pre- and posttest, and the between-subject variable was the ST condition (three levels; implicit, explicit without removal, control group). For the second research question, we also conducted a repeated measures ANOVA with condition as the between-subjects variable (two levels; explicit with/without removal). In addition to classical inference testing using confidence intervals and p values, we conducted Bayesian parameter estimation for the first and second research questions with the open source program JASP (JASP Team, 2020; Wagenmakers, Love, et al., 2018). Bayesian estimation was used to provide additional assurance regarding possible ST effects in learning situations because the Bayes factor can quantify evidence for the null hypothesis (for more advantages, see Wagenmakers, Marsman, et al., 2018). To investigate research question 3, we carried out six moderation analyses in order to obtain a differentiated picture of the ST conditions. In repeated measures ANOVA, we entered the dichotomized moderators (identification with culture of residence, identification with culture of origin, identification with the domain of reading) and the conditions (implicit, explicit without removal, and control; explicit with and without removal). The vocabulary pre- and posttest was the within-subject variable. Listwise deletion was used to handle missing data. The number of missing values was less than 4.6%.

Results

Descriptive findings

Descriptive analyses (see Table 1 and Table A in Supplement 1) revealed that children knew on average four of target words in the pretest (Mpretest = 4.60, SD = 2.81) and eight words in the posttest (Mposttest = 8.56, SD = 3.80). Furthermore, a statistically significant and large correlation between vocabulary pre- and posttest was found, indicating a strong positive association (Cohen, 1988). Additionally, there were positive, moderately strong correlations between both pretest/posttest and cognitive abilities. These coefficients indicate that higher cognitive abilities were associated with higher scores on the vocabulary tests. Furthermore, learners identified highly with the culture of residence and culture of origin on average. Both mean values deviated statistically significantly and substantially from the theoretical mean of 2.5 in positive direction (i.e., above the mean), t(235)Identification culture of residence = 10.33, p < 0.001, d = 0.67; t(228)Identification culture of origin = 16.64, p < 0.001, d = 1.10. The theoretical mean of 2.5 would indicate a neutral response. The effects can be classified as medium and large (Cohen, 1988).

Vocabulary growth in the implicit and explicit without removal ST conditions

Regarding the question of whether language minority children show a lower growth in vocabulary in the (a) implicit and/or (b) explicit ST condition without removal, relative to a control condition, the repeated measures ANOVA revealed a statistically significant main effect of time (vocabulary pre- and posttest). It indicated that there was a statistically significant vocabulary growth of four words on average across all three experimental conditions, Mpretest = 4.51, SD = 2.83; Mposttest = 8.31, SD = 3.88; F(1,179) = 268.84, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.60. This effect size represents a large effect (Cohen, 1988). Planned contrasts revealed no statistically significant difference in vocabulary growth between the implicit (M = 6.34, SD = 0.40) and the control condition (M = 5.89, SD = 0.40) of 0.48 (SE = 0.56), p = 0.212, but provided a statistically significant difference between the explicit without removal (M = 6.93, SD = 0.37) and the control condition (M = 5.89, SD = 0.40) of 1.04 (SE = 0.51), p = 0.028. Furthermore, there was neither a main effect of condition nor an interaction between time and condition. No ST effect on vocabulary growth was found; thus, the empirical data did not support hypotheses 1a and 1b. In the context of a Bayesian mixed-factor ANOVA, an examination of the Q–Q plots revealed that the assumption of normal distribution of the residuals was not violated. The Bayesian estimation (see Table B, Supplement 2) shows that the data were best represented by the model that included time as a factor over the other models, supporting the results of the ANOVA using classical inference testing.

As students of Turkish origin represent the largest subgroup of language minority people in Germany and are also negatively stereotyped as a group low in language ability (Froehlich et al., 2016; Statistisches Bundesamt, 2021), we were interested in whether we find ST effects in this subgroup. The subsample was based on 89 children of Turkish origin who were on average ten years old (M = 9.88, SD = 0.47; 45.5% female; implicit ST n = 24, explicit ST without removal n = 26, explicit ST with removal n = 19, and control condition n = 20). Regarding research question 1, the analysis showed a similar pattern of findings, as no ST effect on vocabulary growth was found, F(2, 67) = 0.93, p = 0.400.

Moreover, we further conducted an analysis with children who were most likely to be threatened by language-related stereotypes. This subsample was also determined based on the language that participants’ reported to speak at home. Given that this subanalysis focused on children who were most likely to be threatened by language-related stereotypes, we excluded, for example, French- and English-speaking children (n = 25) from the sample of language minority students. Turkish-speaking children as well as, for example, Afghan-, Bosnian-, Moroccan-, and Romanian-speaking children remained in the sample. Thus, the sample size for this analysis consisted of 157 children. The analysis revealed also no ST effect on vocabulary growth, F(2, 154) = 0.16, p = 0.854.

Vocabulary growth in the explicit ST condition with and without removal

The repeated measures ANOVA examining whether students’ vocabulary learning differed in the explicit condition with and without removal revealed a statistically significant main effect of time (vocabulary pretest and posttest), F(1,122) = 208.91, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.63. This effect size was deemed large (Cohen, 1988). The main effect of condition and the interaction did not achieve statistical significance. Therefore, the results did not support hypothesis 2. Again, the Q–Q plots of the Bayesian mixed-factor ANOVA indicated that the assumption of normal distribution of the residuals was not violated. Table B in Supplement 2 shows that the model containing only time as a factor best represented the data compared to the other models, again confirming the findings of the ANOVA using classical inference testing.

Moderator analyses

In order to test whether ST effects on vocabulary growth were moderated by (a) identification with culture of residence, (b) identification with culture of origin, and/or (c) the domain identification, separate moderator analyses were conducted. The results revealed no moderation by identification with culture of residence, identification with culture of origin, or identification with the domain of reading (see Table 2). However, identification with the domain of reading was found to be related to vocabulary growth. The planned contrasts showed that for each moderator, the explicit without removal condition differed from the control condition (see Table C in Supplement 3). Hence, hypotheses 3a–c were not supported.

Discussion

Several studies have reported that language minority students showed on average lower vocabulary in the language of instruction compared to native students, whereby vocabulary is an important prerequisite for educational success. Therefore, we examined ST effects as a possible explanation for educational inequalities. More precisely, in a pre-post design, we investigated whether implicitly and/or explicitly induced ST has an impact on vocabulary acquisition and whether students’ vocabulary learning differed for explicit ST with or without removal before posttest, meaning that ST was explicitly tested in a learning rather than an achievement situation (Boucher et al., 2012). Furthermore, we analyzed identification with the culture of residence, origin, and the domain of reading as potential moderators.

Summarized, the results revealed that students had a vocabulary growth of four words on average, regardless of the experimental condition. The amount of growth was consistent with other studies that also focused on vocabulary growth from reading short texts (e.g., El-Khechen et al., 2012; Sander et al., 2018). Concerning the results of the first research question, no ST effect was found in the learning situation regardless of whether the threat was implicitly or explicitly induced. In light of the non-significant main effect of condition and the lower vocabulary growth in the control condition compared to the other conditions, the difference in planned contrasts between the explicit without removal and the control condition can be interpreted as a tendency towards stereotype reactance. Nevertheless, the no ST effect is contrary to our expectations and not in line with previous findings (e.g., Hermann & Vollmeyer, 2016; Sander et al., 2018). Furthermore, referring the second research question, there was no difference in vocabulary growth between the explicit ST condition with and without removal, indicating no ST effect in the learning situation. Therefore, these findings are inconsistent with previous research (Boucher et al., 2012; Rydell & Boucher, 2017).

One explanation for these non-significant findings might be that ST effects have been frequently examined and found in laboratory settings and less often in real world settings (Cullen et al., 2004; Stricker & Ward, 2004). A closer look at mean vocabulary growth among our four experimental groups revealed that children tended to learn more or even similar in all ST conditions than in the control condition, although the differences were not statistically significant. Perhaps the claim that children who also speak a language other than German at home have difficulties learning vocabulary actually motivated the children to make an extra effort. Hence, the results might be interpreted in terms of a tendency towards stereotype reactance (e.g., Kray et al., 2001). Stereotype reactance is based on the theory by Brehm (1966) and is defined as reacting to the threat in a way that defies expectations, meaning that participants tend to refute the induced stereotype and thus increase their performance (Kray et al., 2001). Speaking against such an interpretation is that we only slightly adapted the experimental treatment by Sander et al. (2018), who did find the expected ST effect. Another possible reason could be that the children were unaware of a negative stereotype about families communicating in a language other than German, which is a prerequisite for ST effects to occur. Stang et al. (2021) recently found that Turkish origin elementary school children in Germany hold no achievement-related negative stereotypes about people of Turkish origin. This could indicate that language minority children may be familiar with achievement-related stereotypes but have not internalized them due to their differentiated knowledge of their own group. Similarly, Shelvin et al. (2014) measured stereotype awareness in African American children aged 10 to 12 through a racial stereotype-generation task and found that not all children (44%) named the achievement-related stereotype Blacks are less intelligent than Whites. Children who mentioned this stereotype had a decrease in achievement on a vocabulary subtest compared to children who were unaware of the stereotype. Likewise, Wasserberg’s (2014) findings for African American elementary school children showed that when the test was diagnostic of verbal skills, children who were aware of racial stereotypes performed less well than children who were unaware of them. Smith & Hopkins (2004) also found no ST effect in a sample of African American college students on either arithmetic or spelling tests. The authors assumed that “these students have not incorporated this stereotype into their cognitive schemas because of their own sense of competence” (Smith & Hopkins, 2004, p. 319). Furthermore, our results of no ST effect are consistent with the findings of Chaffee et al. (2020), who investigated the effect of explicit ST in four experiments involving men working on language-related tasks.

Moreover, our findings could be interpreted in light of the replication crisis and a possible publication bias (e.g., Ganley et al., 2013). Although the effects of ST have been empirically demonstrated by a several studies (e.g., Appel et al., 2015; Pennington et al., 2016; Spencer et al., 2016), a study by the Open Science Collaboration (2015) on replicability in psychological science showed that only 36% of 100 replicated studies exhibited statistically significant results. Against this background, many studies examining ST have also investigated the possibility of publication bias. Publication bias was demonstrated and defined by Begg (1994, p. 402) as the fact “that there really are a number of small studies with effect sizes distributed around the null value, but most of these remain unpublished.” Ganley et al. (2013) analyzed a sample of 931 students from childhood to adolescence and could not detect any ST effect regarding gender differences in mathematics. Additionally, the authors found out that non-significant results were either not published or only published alongside significant results. Moreover, Shewach et al. (2019) examined the setting of the studies included in their meta-analysis for possible publication bias. Corresponding with Flore & Wicherts (2015), the authors found the presence of a publication bias, which they argue is inflated to a certain extent yet due to the suppression of null results and due to non-publication of non-significant findings (Shewach et al., 2019).

We also did not find that ST effects were moderated by children’s identification with their culture of residence, culture of origin, or with the domain of reading. These results are contrary to findings for ST in achievement situations (e.g., Baysu & Phalet, 2019; Weber et al., 2018), where, for example, high domain identification has been shown to decrease achievement (e.g., Appel et al., 2011; Pansu et al., 2016; Steele, 1997). Regarding learning situations, the results on identification with culture of origin are consistent with previous research findings, which also found no moderating effect of this variable (e.g., Sander et al., 2018).

Limitations and future directions

Despite this study’s important strengths, such as the pre-post design, certain aspects warrant attention. Due to the small size of language minority subgroups, analyses for these specific groups (e.g., Arabic-, Russian-, Polish-, and Romanian-speaking children) were not possible, who might be more or also differently affected by a language-related threat. Future research may systematically compare students from different language groups which would lead to a more fine-grained picture of threat effects for different groups. To better understand the obtained null effects, it would also be beneficial to assess children’s awareness of negative language-related stereotypes and include this as a potential confounding variable or moderator in the analyses. These information might also have helped to better understand null effects. Additionally, this should also be deliberated in further research examining whether ST is a phenomenon that potentially only occurs in (vocabulary) achievement situations but not in (vocabulary) learning situations in actual classrooms. Moreover, it is not clear whether a motivation effect undermined the possible ST effects, meaning that the explicit threat might have been motivating for language minority students. This conclusion (stereotype reactance) is supported by the results of the planned contrasts.

Moreover, it is important to research at what age children become susceptible to ST. Likewise, it is relevant to examine the development and effects of stereotypes in similar learning situations in secondary school. It should also be examined whether elementary school students, as well as older students, have internalized negative stereotypes about their own group, making ST effects more likely. Moreover, it would be also interesting to investigate ST effects longitudinally to test knowledge or retrieval after several weeks (e.g., Taylor & Walton, 2011). Further, it would be worthwhile to focus on another individual factor, namely, stress (e.g., Wolf, 2017), because stress seems to impair cognitive processes.

However, important strengths can also be mentioned. While previous research typically investigated ST in achievement situations, our study focused on ST in vocabulary learning situations. Going beyond Sander et al. (2018), we included an experimental condition in which ST was removed before posttest. Thus, we sought to determine whether ST in fact impaired children’s learning, rather than access to previously acquired vocabulary in the achievement situation (cf., Boucher et al., 2012).

Conclusion

Overall, the present findings are inconsistent with published ST studies. Therefore, further research in this area is necessary to gain a better understanding of the phenomenon given the heterogeneous findings. But given that the null results regarding vocabulary learning situations among language minority children can be supported by further research, practical and theoretical implications can be derived. Thus, it might still be worthwhile to sensitize teachers with regard to stereotypes and their effects in order to reduce inequalities in the educational system and strengthen educational participation. More specifically, teachers should be sensitized to be especially aware of activating stereotypes in achievement situations as prior studies revealed. In learning situations, activating negative stereotypes explicitly could be motivating. Theoretical implications could be the differentiation of stereotype threat theory. Thus, theory could differentiate of type and domain of activated stereotypes (e.g., language-related vs. gender-related stereotype; language vs. math domain) as well as the distinction between learning and achievement situations. Further, the group of interest could be considered as point of differentiation, e.g., migration background/language minority and/or gender. Thus, the implications of potentially threatening statements, including the emphasis of achievement differences or merely mentioning the results of large international student assessments, could be better understood by focusing different groups of interest and systematically varying their numeric representation in a given educational context and assessing the existence of a negative (or even positive) performance stereotype. This might help to better understand indifferent findings and the critique on stereotype threat theory (Chaffee et al., 2020; Ganley et al., 2013; Shewach et al., 2019).

Data availability

The data described in this article are openly available within the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/dh9er/?view_only=a9b47b491cef45098efc6e8091d2ee6c.

References

Ambady, N., Shih, M., Kim, A., & Pittinsky, T. L. (2001). Stereotype susceptibility in children: Effects of identity activation on quantitative performance. Psychological Science, 12, 385–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00371

Appel, M., & Kronberger, N. (2012). Stereotypes and the achievement gap: Stereotype threat prior to test taking. Educational Psychology Review, 24(4), 609–635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-012-9200-4

Appel, M., Kronberger, N., & Aronson, J. (2011). Stereotype threat impairs ability building: Effects on test preparation among women in science and technology. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 904–913. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.835

Appel, M., Weber, S., & Kronberger, N. (2015). The influence of stereotype threat on immigrants: Review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 900. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00900

Arens, A. K., Trautwein, U., & Hasselhorn, M. (2011). Erfassung des Selbstkonzepts im mittleren Kindesalter: Validierung einer deutschen Version des SDQ I 1 [Self-concept measurement with preadolescent children: Validation of a german version of the SDQ I]. Zeitschrift Für Pädagogische Psychologie, 25(2), 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1024/1010-0652/a000030

Armenta, B. E. (2010). Stereotype boost and stereotype threat effects: The moderating role of ethnic identification. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16(1), 94–98. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017564

Aronson, J., Lustina, M. J., Good, C., Keough, K., Steele, C. M., & Brown, J. (1999). When white men can’t do math: Necessary and sufficient factors in stereotype threat. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35(1), 29–46. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.1998.1371

McElvany, N., & Artelt, C. (2007). Das Berliner Eltern-Kind Leseprogramm: Konzeption und Effekte [The Berlin Parent-Child Reading Program: Conceptual design and evaluation]. Psychologie in Erziehung und Unterricht, 4, 314–332.

El-Khechen, W., Gebauer, M. M., & McElvany, N. (2012). Wortschatzförderung bei Grundschulkindern – Ein Vergleich von Kindern mit und ohne Migrationshintergrund [Vocabulary promotion in elementary school children – A comparison of children with and without a migration background]. Zeitschrift für Grundschulforschung, 5, 48–63.

Zander, L., & Hannover, B. (2013). Die Bedeutung der Identifikation mit der Herkunftskultur und mit der Aufnahmekultur Deutschland für die soziale Integration Jugendlicher mit Migrationshintergrund in ihrer Schulklasse [How identification with culture of origin and culture of residence relates to the social integration of immigrant adolescents in German classrooms]. Zeitschrift für Entwicklungspsychologie und Pädagogische Psychologie, 45, 142–160. https://doi.org/10.1026/0049-8637/a00009

McElvany, N., Ohle, A., El-Khechen, W., Hardy, I., & Cinar, M. (2017). Förderung sprachlicher Kompetenzen – Das Potenzial der Familiensprache für den Wortschatzerwerb aus Texten [Supporting language competencies – The potential of the family language for vocabulary acquisition from texts]. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie, 31(1), 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1024/1010-0652/a000189

Sander, A., Ohle-Peters, A., McElvany, N., Zander, L., & Hannover, B. (2018). Stereotypenbedrohung als Ursache für geringeren Wortschatzzuwachs bei Grundschulkindern mit Migrationshintergrund [Stereotype threat as a cause for lower vocabulary growth among elementary school children with migration background]. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 21, 177–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-017-0763-1

Stang, J., König, S., & McElvany, N. (2021). Implizite Einstellungen von Kindern im Grundschulalter gegenüber Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund [Implicit attitudes of elementary school children towards people with a migrant background]. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1024/1010-0652/a000320

Baron, A. S., & Banaji, M. R. (2006). The development of implicit attitudes: Evidence of race evaluations from ages 6 and 10 and adulthood. Psychological Science, 17(1), 53–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01664.x

Bar-Tal, D. (1996). Development of social categories and stereotypes in early childhood: The case of “the Arab” concept formation, stereotype and attitudes by Jewish children in Israel. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 20, 341–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(96)00023-5

Baysu, G., & Phalet, K. (2019). The up-and downside of dual identity: Stereotype threat and minority performance. Journal of Social Issues, 75(2), 568–591. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12330

Begg, C. B. (1994). Publication bias. In H. Cooper & L. V. Hedges (Eds.), The handbook of research synthesis (pp. 399–409). Russell Sage Foundation.

Berry, J. W., Phinney, J. S., Sam, D. L., & Vedder, P. (2006). Immigrant youth: Acculturation, identity, and adaptation. Applied Psychology, 55(3), 303–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2006.00256.x

Bialystok, E., Luk, G., Peets, K. F., & Yang, S. (2010). Receptive vocabulary differences in monolingual and bilingual children. Bilingualism, 13(4), 525–531. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728909990423

Biemiller, A. (2005). Size and sequence in vocabulary development. In E. H. Hiebert & M. L. Kamil (Eds.), Teaching and learning vocabulary: Bringing research into practice (pp. 223–242). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bosman, A. M., & Janssen, M. (2017). Differential relationships between language skills and working memory in Turkish-Dutch and native-Dutch first-graders from low-income families. Reading and Writing, 30(9), 1945–1964. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-017-9760-2

Boucher, K. L., Rydell, R. J., Van Loo, K. J., & Rydell, M. T. (2012). Reducing stereotype threat in order to facilitate learning. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42(2), 174–179. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.871

Brehm, J. W. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance. Academic Press.

Calvo, A., & Bialystok, E. (2014). Independent effects of bilingualism and socioeconomic status on language ability and executive functioning. Cognition, 130(3), 278–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2013.11.015

Chaffee, K. E., Lou, N. M., & Noels, K. A. (2020). Does stereotype threat affect men in language domains? Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1302. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01302

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Erlbaum.

Cole, B., Matheson, K., & Anisman, H. (2007). The moderating role of ethnic identity and social support on relations between well-being and academic performance. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 37, 592–615. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2007.00176.x

Cullen, M. J., Hardison, C. M., & Sackett, P. R. (2004). Using SAT-grade and ability-job performance relationships to test predictions derived from stereotype threat theory. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(2), 220–230. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.2.220

DeKeyser, R. M. (2003). Implicit and explicit learning. In C. J. Doughty & M. H. Long (Eds.), The handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 313–348). Blackwell Publishing.

Dovidio, J. F., Hewstone, M., Glick, P., & Esses, V. M. (2010). Prejudice, stereotyping and discrimination: Theoretical and empirical overview. In J. F. Dovidio, M. Hewstone, P. Glick, & V. M. Esses (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of prejudice, stereotyping and discrimination (pp. 3–29). SAGE.

Elgort, I. (2011). Deliberate learning and vocabulary acquisition in a second language. Language Learning, 61(2), 367–413. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2010.00613.x

Ellis, R., Loewen, S., Elder, C., Erlam, R., Philp, J., & Reinders, H. (2009). Implicit and explicit knowledge in second language learning, testing and teaching. Multilingual Matters.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Flore, P. C., & Wicherts, J. M. (2015). Does stereotype threat influence performance of girls in stereotyped domains? A Meta-Analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 53(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2014.10.002

Froehlich, L., Martiny, S. E., Deaux, K., Goetz, T., & Mok, S. Y. (2016). Being smart or getting smarter: Implicit theory of intelligence moderates stereotype threat and stereotype lift effects. British Journal of Social Psychology, 55(3), 564–587. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12144

Froehlich, L., Mok, S. Y., Martiny, S. E., & Deaux, K. (2018). Stereotype threat-effects for Turkish-origin migrants in Germany: Taking stock of cumulative research evidence. European Educational Research Journal, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904118807539

Ganley, C. M., Mingle, L. A., Ryan, A. M., Ryan, K., Vasilyeva, M., & Perry, M. (2013). An examination of stereotype threat effects on girls’ mathematics performance. Developmental Psychology, 49(10), 1886–1897. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031412

Graves, M. F. (2016). The vocabulary book: Learning and instruction. Teachers College Press.

Heller, K. A., & Perleth, C. (2000). Kognitiver Fähigkeitstest für 4.-12. Klassen, Revision (KFT 4–12+R) [Cognitive ability test for 4th-12th grades, revision (KFT 4–12+R)]. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Hermann, J. M., & Vollmeyer, R. (2016). Stereotype threat in der Grundschule [Stereotype threat in primary school]. Zeitschrift für Entwicklungspsychologie und Pädagogische Psychologie, 48(1), 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1026/0049-8637/a000143

Hoff, E. (2018). Bilingual development in children of immigrant families. Child Development Perspectives, 12(2), 80–86. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709906X11366210.1111/cdep.12262

JASP Team (2020). JASP (Version 0.12.2) [Computer software]. Retrieved from https://jasp-stats.org/.

Karami, A., & Bowles, F. A. (2019). Which strategy promotes retention? Intentional vocabulary learning, incidental vocabulary learning, or a mixture of both? Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 44(9), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.3316/ielapa.895245441422402

Keller, J. (2007). Stereotype threat in classroom settings: The interactive effect of domain identification, task difficulty and stereotype threat on female students’ maths performance. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77, 323–338. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709906X113662

Keller, J., & Dauenheimer, D. (2003). Stereotype threat in the classroom: Dejection mediates the disrupting threat effect on women’s math performance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 371–381. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167202250218

Kite, M. E., & Whitley, B. E., Jr. (2016). The psychology of prejudice and discrimination (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Kray, L. J., Thompson, L., & Galinsky, A. (2001). Battle of the sexes: Gender stereotype confirmation and reactance in negotiations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 942–958. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.80.6.942

Martin, C. L., & Ruble, D. N. (2010). Patterns of gender development. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 353–381. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100511

Martiny, S. E., Mok, S. Y., Deaux, K., & Froehlich, L. (2014). Effects of activating negative stereotypes about Turkish-origin students on performance and identity management in German high schools. Revue Internationale De Psychologie Sociale, 27(3), 205–225.

Marulis, L. M., & Neuman, S. B. (2010). The effects of vocabulary intervention on young children’s word learning: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 80(3), 300–335. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654310377087

Mathôt, S., Schreij, D., & Theeuwes, J. (2012). OpenSesame: An open-source, graphical experiment builder for the social sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 44, 314–324. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-011-0168-7

McDaniel, M. A., Brown, P. C., & Roediger III, H. L. (2014). Make it stick: The science of successful learning. Belknap Cambridge MA.

McLaughlin Lyons, E., Simms, N., Begolli, K. N., & Richland, L. E. (2018). Stereotype threat effects on learning from a cognitively demanding mathematics lesson. Cognitive Science, 42(2), 678–690. https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.12558

Mullis, I. V. S., Martin, M. O., Foy, P., & Hooper, M. (2017). PIRLS 2016 international results in reading. Chestnut Hill, MA: TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, Boston College.

Nadler, J. T., & Clark, M. H. (2011). Stereotype threat: A meta-analysis comparing African Americans to Hispanic Americans. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41(4), 872–890. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00739.x

Nation, I. S. P. (2013). Learning vocabulary in another language (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Neuville, E., & Croizet, J. C. (2007). Can salience of gender identity impair math performance among 7–8 years old girls? The moderating role of task difficulty. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 22(3), 307–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03173428

Nguyen, A. D., & Benet-Martínez, V. (2013). Biculturalism and adjustment: A meta-analysis. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44, 122–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022111435097

Nguyen, H. H. D., & Ryan, A. M. (2008). Does stereotype threat affect test performance of minorities and women? A meta-analysis of experimental evidence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1314–1334. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012702

Novita, S., Lockl, K., & Gnambs, T. (2021). Reading comprehension of monolingual and bilingual children in primary school: The role of linguistic abilities and phonological processing skills. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-021-00587-5

OECD. (2019). Education GPS. Retrieved from http://gpseducation.oecd.org. Accessed 10 July 2020.

Open Science Collaboration. (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science, 349, 943. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac4716

Pansu, P., Régner, I., Max, S., Colé, P., Nezlek, J. B., & Huguet, P. (2016). A burden for the boys: Evidence of stereotype threat in boys’ reading performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 65, 26–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2016.02.008

Pennington, C. R., Helm, D., Levy, A. R., & Larkin, D. T. (2016). Twenty years of stereotype threat research: A review of psychological mediators. PLoS ONE, 11(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone0146487

Ruble, D. N., Alvarez, J., Bachman, M., & Cameron, J. (2004). The development of a sense of “we”: The emergence and implications of children’s collective identity. In M. Bennett & F. Sani (Eds.), The development of social self (pp. 29–76). Psychology Press.

Rydell, R. J., & Boucher, K. L. (2017). Stereotype threat and learning. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 56, 81–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aesp.2017.02.002

Schmader, T., Johns, M., & Forbes, C. (2008). An integrated process model of stereotype threat on performance. Psychological Review, 115, 336–356. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.115.2.336

Shelvin, K. H., Rivadeneyra, R., & Zimmerman, C. (2014). Stereotype threat in African American children: The role of Black identity and stereotype awareness. Revue Internationale De Psychologie Sociale, 27(3), 175–204.

Shewach, O. R., Sackett, P. R., & Quint, S. (2019). Stereotype threat effects in settings with features likely versus unlikely in operational test settings: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 104(12), 1514–1534. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000420

Smith, C. E., & Hopkins, R. (2004). Mitigating the impact of stereotypes on academic performance: The effects of cultural identity and attributions for success among African American college students. Western Journal of Black Studies, 28(1), 312–321.

Spencer, S. J., Logel, C., & Davies, P. G. (2016). Stereotype threat. Annual Review of Psychology, 67, 415–437. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-073115-103235

Stanat, P., Becker, M., Baumert, J., Lüdtke, O., & Eckhard, A. G. (2012). Improving second language skills of immigrant students: A field trial study evaluating the effects of a summer learning program. Learning and Instruction, 22, 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2011.10.002

Statistisches Bundesamt (Hrsg.). Datenreport 2021. Ein Sozialbericht für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland [Data report 2021: A social report for the Federal Republic of Germany]. Bonn: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung.

Steele, C. M. (1997). A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. American Psychologist, 52, 613–629. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003066X.52.6.613

Steele, C. M., & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 797–811. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.797

Steele, C. M., Spencer, S. J., & Aronson, J. (2002). Contending with group image: The psychology of stereotype and social identity threat. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 34, 379–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(02)80009-0

Stricker, L. J., & Ward, W. C. (2004). Stereotype threat, inquiring about test takers’ ethnicity and gender, and standardized test performance. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(4), 665–693. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02564.x

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of Intergroup Relations (pp. 7–24). Nelson-Hall.

Taylor, V. J., & Walton, G. M. (2011). Stereotype threat undermines academic learning. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37, 1055–1067. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211406506

Vidal, K. (2011). A comparison of the effects of reading and listening on incidental vocabulary acquisition. Language Learning, 61(1), 219–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2010.00593.x

Wagenmakers, E. J., Love, J., Marsman, M., Jamil, T., Ly, A., Verhagen, J., ... Meerhoff, F. (2018a). Bayesian inference for psychology. Part II: Example applications with JASP. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 25(1), 58–76. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-017-1323-7

Wagenmakers, E. J., Marsman, M., Jamil, T., Ly, A., Verhagen, J., Love, J., ... & Morey, R. D. (2018b). Bayesian inference for psychology. Part I: Theoretical advantages and practical ramifications. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 25(1), 35–57. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-017-1343-3

Washbrook, E., Waldfogel, J., Bradbury, B., Corak, M., & Ghanghro, A. A. (2012). The development of young children of immigrants in Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Child Development, 83(5), 1591–1607. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01796.x

Wasserberg, M. J. (2014). Stereotype threat effects on African American children in an urban elementary school. The Journal of Experimental Education, 82, 502–517. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2013.876224

Wasserberg, M. J. (2017). High-achieving African American elementary students’ perspectives on standardized testing and stereotypes. The Journal of Negro Education, 86(1), 40–51. https://doi.org/10.7709/jnegroeducation.86.1.0040

Webb, S. (2008). The effects of context on incidental vocabulary learning. Reading in a Foreign Language, 20, 232–245.

Weber, S., Appel, M., & Kronberger, N. (2015). Stereotype threat and the cognitive performance of adolescent immigrants: The role of cultural identity strength. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 42, 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2015.05.001

Weber, S., Kronberger, N., & Appel, M. (2018). Immigrant students’ educational trajectories: The influence of cultural identity and stereotype threat. Self and Identity, 17(2), 211–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2017.1380696

Wendt, H., Bos, W., Tarelli, I., Vaskova, A., & Walzebug, A. (2016). IGLU/TIMSS 2011 – Skalenhandbuch zur Dokumentation der Erhebungsinstrumente und Arbeit mit den Datensätzen [IGLU/TIMSS 2011 – Scale manual for documenting the survey instruments and working with the data sets]. Münster: Waxmann.

Wolf, O. T. (2017). Stress and memory retrieval: Mechanisms and consequences. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 14, 40–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2016.12.001

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG) [392231161].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

According to the unanimous positive vote of the Ethics Committee of the TU Dortmund University, the research project complies with the ethical guidelines for conducting scientific research. Participation was voluntary and took place only if parental consent was given prior to data collection.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sabrina Koenig. Center for Research on Education and School Development (IFS), TU Dortmund University.

Current themes of research.

Attitudes. Stereotypes. Stereotype threat.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education.

Stang, J., König, S., & McElvany, N. (2021). Implizite Einstellungen von Kindern im Grundschulalter gegenüber Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund [Implicit attitudes of elementary school students towards people with migrant background]. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie, 1–14. Online first. 10.1024/1010-0652/a000320.

Justine Stang-Rabrig. Center for Research on Education and School Development (IFS), TU Dortmund University.

Current themes of research.

Stereotype threat. Instructional quality. Well-being.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education.

Kleinkorres, R., Stang, J., & McElvany, N. (2020). A longitudinal analysis of reciprocal relations between students’ well-being and academic achievement. Journal for Educational Research Online, 12, 114–165. 10.25656/01:20975.

Lepper, C., Stang, J., & McElvany, N. (2021). Gender differences in text-based interest: Text characteristics as underlying variables. Reading Research Quarterly. Advance online publication. 10.1002/rrq.420.

Stang, J., König, S., & McElvany, N. (2021). Implizite Einstellungen von Kindern im Grundschulalter gegenüber Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund [Implicit attitudes of elementary school students towards people with migrant background]. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie, 1–14. Online first. 10.1024/1010-0652/a000320.

Stang, J., & Urhahne, D. (2016). Stabilität, Bezugsnormorientierung und Auswirkungen von Lehrkrafturteilen [Stability, reference norm orientation, and effects of judgment accuracy]. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie, 30, 251–262. 10.1024/1010-0652/a000190.

Bettina Hannover. Department of Educational Science and Psychology, Freie Universität Berlin, Germany.

Current themes of research.

Impact of self and identity on the academic development of girls and boys and of students from different ethnic backgrounds.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education.

Bauer, C., & Hannover, B. (2021). Do only White or Asian males belong in genius organizations? How academic organizations’ fixed theories of excellence help or hinder different student groups’ sense of belonging. Frontiers in Psychology. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.631142.

Hannover, B., Kreutzmann, M., Haase, J., & Zander, L. (2020). Growing together – Effects of a school-based intervention promoting positive self-beliefs and social integration in recently immigrated children. International Journal of Psychology, 55, 713–722. 10.1002/ijop.12653 .

Harks, M., & Hannover, B. (2019). Feeling socially embedded and engaging at school. The impact of peer status, victimization experiences, and teacher awareness of peer-relations in class. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 35, 95–818. 10.1007/s10212-019-00455-3.

Lysann Zander. Institute of Education, Leibniz Universität Hannover, Germany.

Current themes of research.

Issues of classroom heterogeneity regarding identity-relevant aspects such as students’ linguistic background, ethnic group membership, or socioeconomic status. Causes of systematic inequalities in terms of learning outcomes and sense of belonging.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education.

Dufner, M., Reitz, A., & Zander, L. (2015). Antecedents, consequences, and mechanisms: On the longitudinal interplay between academic self-enhancement and psychological adjustment. Journal of Personality, 83(5), 511–522. 10.1111/jopy.12128.

Zander, L., Brouwer, J., Jansen, E., Crayen, C., & Hannover, B. (2018). Academic self-efficacy, growth mindsets, and university students’ integration in academic and social support networks. Learning and Individual Differences, 62, 98–107. 10.1016/j.lindif.2018.01.012.

Zander, L., Chen, I., & Hannover, B. (2019). Who asks whom for help in mathematics? A sociometric analysis of adolescents’ help-seeking within and beyond clique boundaries. Learning and Individual Differences, 72, 49–58. 10.1016/j.lindif.2019.03.002.

Zander, L., Höhne, E., Harms, S., Pfost, M., & Hornsey, M. J. (2020). When grades are high but self-efficacy is low: Unpacking the confidence gap between girls and boys in mathematics. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 552355. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.552355.

Nele McElvany. Center for Research on Education and School Development (IFS), TU Dortmund University.

Current themes of research.

Educational processes from psychological and pedagogical perspectives. Research on individual, social, and institutional conditions of educational processes and outcomes.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education.

Becker, M., & McElvany, N. (2018). The interplay of gender and social background: A longitudinal study of interaction effects in reading attitudes and behaviour. British Journal of Education Psychology, 88(4), 529–549. 10.1111/bjep.12199.

Kigel, R. M., McElvany, N., & Becker, M. (2015). Effects of immigrant background on text comprehension, vocabulary, and reading motivation: A longitudinal study. Learning and Instruction, 35, 73–84. 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2014.10.001.

McElvany, N., Ferdinand, H. D., Gebauer, M. M., Bos, W., Huelmann, T., Köller, O., & Schöber, C. (2018). Attainment-aspiration gap in students with a migration background: The role of self-efficacy. Learning and Individual Differences, 65, 159–166. 10.1016/j.lindif.2018.05.002.

McElvany, N., Schroeder, S., Baumert, J., Schnotz, W., Horz, H., & Ullrich, M. (2012). Cognitively demanding learning materials with texts and instructional pictures: teachers’ diagnostic skills, pedagogical beliefs and motivation. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 27(3), 403–420. 10.1007/s10212-011-0078-1.

Steinmayr, R., Crede, J., McElvany, N., & Wirthwein, L. (2016). Subjective well-being, test anxiety, academic achievement: Testing for reciprocal effects. Frontiers in Psychology, 6:1994. 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01994.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

König, S., Stang-Rabrig, J., Hannover, B. et al. Stereotype threat in learning situations? An investigation among language minority students. Eur J Psychol Educ 38, 841–864 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-022-00618-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-022-00618-9