Abstract

In this paper, I study the conditions under which a CSR leader, that is a firm which commits to invest in socially responsible activities prior to its competitor, can develop a first-mover advantage. A price-setting duopoly market with horizontally differentiated products is considered, where firms can increase the willingness to pay of the consumers of their products by investing in socially responsible activities. It is shown that if the investment in CSR is perfectly specific to the CSR leader and does not spill over to the CSR follower, the CSR leader achieves higher profits. Hence, a first-mover advantage arises. If however, CSR investment spills over to and hence benefits also the CSR follower by increasing the follower sales, then a second-mover advantage might arise for the follower. A characterization is provided for the influence of the intensity of competition and the level of spillovers on the relative and absolute level of CSR activities and the firms’ incentives to engage in CSR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (henceforth CSR) plays an important role in today’s market environment and ranks high on the corporate strategy agenda. Investors and consumers pressure companies to consider social and environmental issues (see, e.g., Manasakis 2018; Fernández-Kranz and Santalo 2010; Kitzmueller and Shimshack 2012; Starks 2009; Mohr et al. 2001) and CSR reporting has become mainstream among big companies. In the past, CSR research has been primarily concerned with defining and categorizing CSR activities and empirically investigating the link between corporate social performance and corporate financial performance, although without arriving at clear-cut results (McWilliams et al. 2006; Baron 2001; McWilliams and Siegel 2000). In recent years, an increasing number of researchers have employed game-theoretic models to study the long-term investment characteristics of CSR decisions and its impact on firm and industry performance. An important conclusion that can be drawn is that if a firm’s stakeholders have social preferences, then engaging in CSR can be fully compatible with profit-maximizing behavior (see Kitzmueller and Shimshack 2012; Bénabou and Tirole 2010; Lyon and Maxwell 2008).To contrast such a type of investment from “altruistic” or “coerced” CSR, the term “strategic corporate social responsibility” has been introduced (see Baron 2001; Husted and de Jesus Salazar 2006; Piga 2002; Heslin and Ochoa 2008).Footnote 1

The issue of first-mover or second-mover advantages has been hotly debated in the strategy and economics literature with a variety of insightful and testable results (see, e.g., Lieberman and Montgomery 1988, 1998, and Kopel and Löffler 2008 for references). In contrast, in the CSR literature only very few authors devote space to this issue despite the obvious importance for firms engaged in CSR activities. Among these exceptions are Reinhardt (1998) and Vogel (2005), who point out that it is difficult to keep CSR activities specific to a firm’s strategy and to profit in the long run. Their argument is succinctly summarized by a comment in The Economist (2008): “First-mover advantage soon passes. After a while, for example, everybody turns green, and the winners are the companies with the best execution. One large consultancy advises its big clients to be number two or three on corporate responsibility rather than number one.” In contrast, Tetrault Sirsly and Lamertz (2008) argue that a CSR leader can maintain a first-mover advantage if it develops “... a strategic CSR initiative that is central to the firm mission, visible to stakeholders and with firm-specific benefits beyond those of public goods.” (p. 360).

In the present paper, I try to advance this line of research on CSR leadership by introducing a formal model to see under which conditions a first-mover or a second-mover advantage arises. In particular, I address the following research questions. I ask if the CSR leader, i.e., the firm which invests in CSR before the rival, always achieves a first-mover advantage. Furthermore, under which circumstances does a CSR follower obtain higher profits? I also study the incentives to invest in CSR. Does the CSR leader or the CSR follower have higher incentives to engage in CSR activities? Who has a higher absolute level of CSR activities? Then, I explore the influence of “CSR spillovers.” How do these results change if “CSR spillovers” exist, i.e., if the CSR leader’s activity also benefits the rival. How does this depend on the level of CSR spillovers? Finally, I explore the influence of competition. How do the results depend on the degree of competition in the industry? Is a higher degree of competition in an industry beneficial for investments in CSR or not?

The main findings of the present study are as follows. If CSR activities are specific to the CSR leader, i.e., if there are no spillovers to the rival or spillovers are very low, then in line with Tetrault Sirsly and Lamertz (2008) I find that a first-mover advantage exists. If CSR spillovers are higher, then there is a second-mover advantage for the CSR follower. The result that the CSR leader achieves higher profits than the CSR follower in the case of perfectly appropriable CSR investments is intuitive and somehow expected. What is surprising, however, is that the level of CSR spillovers for which a first-mover advantage can be sustained is in fact very low. In other words, although the benefit of CSR investments by the leader is almost fully proprietary, to be the first firm which invests in CSR does not pay off in terms of profits since even the smallest opportunity to free-ride on the leader’s investment gives the follower a competitive advantage. This confirms Reinhardt (1998) and Vogel (2005) who both have raised doubts that CSR leadership can lead to a competitive advantage in the long run. The second notable finding in my paper is that for the leader and the follower there is an asymmetry in incentives to engage in CSR which depends on the intensity of competition. With increasing intensity of competition and low spillovers, the CSR leader first decreases CSR efforts, but then increases CSR efforts again. This contrasts with the CSR efforts of the CSR follower, which decrease throughout for increasing intensity of competition. If CSR spillovers are sufficiently high, then the CSR follower’s level of CSR is higher than the CSR leader’s level and the CSR efforts of the CSR follower now first decrease for increasing competition, but then start increasing again. The finding that the interaction between CSR spillovers, CSR activities and the level of competition is rather complex leads to the conclusion that it might be difficult to show empirically which firm has a higher incentive to engage in CSR, since the answer depends on factors which are quite hard to measure accurately. With regard to the ongoing discussion among strategy scholars about the relationship between specific components of corporate social performance and corporate financial performance (e.g., Surroca et al. 2010; Brammer and Millington 2008; Godfrey et al. 2009), my paper shows that even in an ideal setting where the only effect of CSR engagements is to lead to higher prices by increasing the consumers’ willingness to pay, CSR does not necessarily yield a competitive advantage for the first-mover. The occurrence of a competitive advantage depends in an intricate way on contextual factors like the substitutability between the firms’ products, on strategic choices like the timing of CSR engagements, and on particular elements of corporate social performance which are captured here by CSR spillovers. Finally, my study also sheds light on the issue of convergence of CSR practices. Being aware of reputation spillovers, industry leaders oftentimes pressure and support less socially responsible competitors to imitate their CSR practices (Misani 2010; Vogel 2005). Although strategically motivated, this then results in the leading firm giving up its differentiation and first-mover advantage based on its CSR expertise. Consequently, since all firms converge on their CSR practices, empirical studies show no or a rather weak link between corporate social and corporate financial performance.

2 Related literature

My paper is related to several streams of CSR research.Footnote 2 First, the literature which considers CSR as a strategic tool to differentiate a firm’s product or service in markets with imperfect competition is closely related. A profit-maximizing firm tries to achieve a competitive advantage through CSR activities by targeting customers with social preferences and a higher willingness to pay (see Fernández-Kranz and Santalo 2010; Kitzmueller and Shimshack 2012). To achieve a certain level of CSR, firms embody their offerings with CSR attributes (e.g., organic produce, animal test-free cosmetics) or use CSR-related signals (e.g., fair trade label). To consumers, these activities convey the message that firms actively support CSR and therefore they are more reliable, trustworthy, and their products of higher quality. As a consequence, consumers are willing to pay a higher price for the product with the CSR attribute (e.g., Heslin and Ochoa 2008; McWilliams and Siegel 2001). In Bagnoli and Watts (2003) firms are linking the provision of a public good (CSR or environmentally friendly activities) to sales of their private goods in quantity and price competition. As one of the main results they find that in most cases, too little of the public good is provided. For further papers along these lines, see for example Kanniainen and Pietarila (2006), Toolsema (2009), Garcia-Gallego and Georgantzis (2009), and Chen (2001). In contrast to these papers, we consider vertical and horizontal differentiation, CSR spillovers, and assume that the CSR leader invests in CSR before the CSR follower does.

Second, a number of papers have studied the relationship between competition and the strategic use of CSR, with conflicting conclusions. Kopel and Lamantia (2018) summarize this literature and study an evolutionary setting of mixed oligopolistic competition between profit-maximizing firms and socially concerned firms. Bagnoli and Watts (2003) find an inverse relationship between the intensity of competition and provision of CSR, i.e., increasing market competition leads to decreasing levels of CSR activities. Fisman et al. (2006) use a signaling model and conclude that strategic CSR is more likely to be observed when the intensity of competition in the product market is higher; see also more recently Harjoto and Jo (2011). The present paper contributes to this literature on strategic CSR theories, but I find that the relation between the intensity of competition and the level of CSR activity is ambiguous and asymmetric for the CSR leader and the CSR follower.

Third and finally, existing contributions on CSR or environmental leadership mainly have a conceptual or empirical focus. See, for example, Tetrault Sirsly and Lamertz (2008), Bansal and Hunter (2003), or Nehrt (1996). More recently, Chen et al. (2016) study a differentiated Cournot duopoly where only one firm invests in CSR and the rival suffers from negative spillovers due to reputation effects of not investing in CSR. Investments of the CSR firm increase the consumers’ willingness to pay, but also increase its marginal production costs. Firms determine their production quantities either simultaneously or one of the firms chooses the quantity first while the rival chooses second (Cournot–Stackelberg market competition). They characterize the influence of spillovers and the intensity of competition on the firms’ profits and CSR investments like I do, but they do not address the question under which conditions CSR leadership (i.e., investing first in CSR before the rival does) leads to a first-mover advantage. A similar analysis is provided by Wang et al. (2018). The difference here is that the CSR firm does not make demand-enhancing investments with (negative) spillovers, but that the CSR firm maximizes an extended objective function which includes profit and consumer surplus. Arya and Mittendorf (2013) consider a setting where both firms make costly demand-enhancing investments for their own product (like I do), but also allow the firms to make direct costly investments that reduce the rival’s demand. Both firms purchase an input from a common supplier. In their setting, all investments are made simultaneously (and not sequentially as in the present paper) and they are concerned with the question how the investment patterns change if one of the firms integrates with the supplier.

3 The model

Consider two firms, the CSR leader and the CSR follower, that invest in CSR and set the prices for their differentiated products. The firms’ unit production costs are constant and are given by c. The CSR leader benefits from investing in CSR earlier than the CSR follower. The follower, on the other hand, can free ride on these CSR investments, thus giving the CSR leader a disincentive to engage in CSR. Demand is captured by the following equations,Footnote 3

The prices of the products of the CSR leader and the CSR follower are \(p_{1}\) and \(p_{2}\), respectively. The parameter a denotes the reservation price. The variables \(x_{i}\) (\(i=1,2\)) denote the quantity of firm i’s product bought by the representative customer. The parameter \(\gamma \) is a measure of the degree of substitutability (or horizontal differentiation) between the two products. For \(\gamma =0\), the two products are independent, whereas for \(\gamma =1\) they are perfect substitutes. In the analysis, I will use the differentiation parameter \(\gamma \in [0,1)\) as a measure of the intensity of competition in the market, where a higher degree of differentiation (low value of \(\gamma \)) captures a lower intensity of competition and vice versa (e.g., Vives 2008). The CSR investments of the leader and the follower are \(s_{1}\) and \(s_{2}\), respectively. The associated CSR investment costs are of the form \(s_{i}^{2}\) (see Garella and Petrakis (2008)). CSR spillovers are captured by the parameters \(\theta _{1},\theta _{2} \in [0,1]\).Footnote 4 As is common in the CSR literature, we assume that CSR investments increase the consumers’ willingness to pay for a firm’s product by a shift of the demand.Footnote 5 Hence, investments in CSR are akin to investments in the qualities of the products (vertical differentiation); see, e.g., McWilliams et al. (2006), and also Häckner (2000), Symeonidis (2003). The CSR investment of one firm positively influences the demand of the other firm, i.e., the impact of CSR investments “spills over” to the rival firm. If CSR activities are highly firm-specific and maybe can be protected by legal means, then the focal firm can reap the full benefits.Footnote 6 However, more often than not, the benefits of CSR activities are only imperfectly appropriable, which means that they cannot be defended against imitation by competitors (Reinhardt 1998). If the CSR follower copies and improves the green attributes of the CSR leading firm, it can raise the demand for its product without having to bear the full development costs.Footnote 7

The parameters \(\theta _{1}\) and \(\theta _{2}\) capture the firms’ abilities to protect their CSR investments against appropriation or imitation by competitors. Furthermore, in the CSR leader–follower setting which I consider in this paper, it seems sensible to assume that spillovers are asymmetric. In particular, it seems plausible to assume that \(\theta _{1}\le \theta _{2}\), because the CSR follower can free ride on the CSR efforts of the leader. To keep the model as simple as possible, I assume that \(\theta _{1}=0\), so that with \(0\le \theta _{2}=\theta \le 1\) the general (inverse) demand system from above reduces to

Since I am interested in price competition, inverting the system (1) leads to the direct demands

which will be used for the subsequent analysis. The demand system exhibits a discontinuity at \(\gamma =1\) (products are perfect substitutes) which is not eliminated by the introduction of CSR. In what follows, I will assume that the products are sufficiently differentiated, i.e., \(\gamma <\gamma _{\max } =0.810736\). This guarantees that the equilibrium of the game is in the interior and all second-order conditions are satisfied (see similarly, Garella and Petrakis (2008)). The corresponding profits of the firms (net of investment costs) are given by

The timing of the three-stage game is as follows. In the first stage, the CSR leader selects the level of CSR investments \(s_{1}\) such that its profit \(\pi _{1}\) is maximized. This level is observed by the CSR follower. In stage 2, the follower selects its level of CSR investments \(s_{2}\) such that its profit \(\pi _{2}\) is maximized. Finally, in stage 3 the firms simultaneously choose the prices of their products such that the firm’s profits (given both firms’ CSR investments) are maximized. The game is solved by backward induction.

4 CSR investments, prices, and profits

I now characterize the equilibrium of this game. Employing backward induction, I first solve the price competition stage, where the CSR leader and the CSR follower choose prices simultaneously. Solving the first-order conditions, i.e., \(\partial \pi _{1}/\partial p_{1}=0,\partial \pi _{2}/\partial p_{2}=0\), yields the prices of the CSR leader (firm 1) and the CSR follower (firm 2) as functions of the CSR investments:

Note that a firm’s CSR activity increases its own price, but the marginal effect is smaller for the CSR leader (if spillovers are positive). Moreover, the effect of a firm’s CSR activity on the competitor might be different for the CSR leader and CSR follower. For a given degree of substitutability of the two products, if spillovers are sufficiently large, the CSR activity of the CSR leader might lead to an increase in the price of the CSR follower if \(\theta >\gamma /(2-\gamma ^{2})\). Taken together, it seems that CSR spillovers have the effect of reducing the incentives for the CSR leader to engage in CSR. Note furthermore, that in the case where both firms select an identical CSR activity level (\(s_{1}=s_{2}>0\)), the CSR follower selects a higher price than the CSR leader if spillovers are positive.

I am now turning to the CSR follower’s selection of the level of CSR activities \(s_{2}\) at stage 2. The CSR follower observes the CSR activity level of the leader and subsequently chooses its profit-maximizing level of CSR activities anticipating the prices set at the market stage. Inserting (3) into firm 2’s profit function, the first-order condition of the CSR follower yields

Note that as long as \(\theta <\gamma /(2-\gamma ^{2})\), an increase in the CSR activities of the leader leads to a decrease in the follower’s CSR engagement. The follower’s incentive to invest in CSR decreases, since the follower can free ride on the CSR activity of the leader. If spillovers are high however, \(\theta >\gamma /(2-\gamma ^{2})\), then the leader’s incentive to invest in CSR decreases and, therefore, the follower has to increase its own CSR activities to counterbalance this effect.

In stage 1, the CSR leader chooses its CSR activity level, anticipating the response of the CSR follower at the subsequent stage and the prices to be chosen in the market stage. Solving the CSR leader’s optimization problem subject to the CSR follower’s reaction function (4) results in the following level of CSR activity for the leader in equilibriumFootnote 8

Using this optimal investment level, we can now solve for the optimal CSR investment of the follower,

where the expression in the numerator is \(N=6(3+\theta )+2\gamma (3+5\theta -2\theta ^{2})-\gamma ^{2}(35+\theta +4\theta ^{2})-\gamma ^{3}(15+6\theta -\theta ^{2})+\gamma ^{4}(15+\theta ^{2})+\gamma ^{5}(7+\theta )-2\gamma ^{6} -\gamma ^{7}\). Using these equilibrium levels of the CSR activities of the firms, the prices and profits in equilibrium can be expressed as

5 First-mover advantage and the influence of competition and spillover levels

I can now use the equilibrium outcomes and (net) profits to answer the questions raised in the introduction. That is, I investigate the conditions under which the CSR leader achieves a first-mover advantage and study the influence of CSR spillovers and the degree of competition on the level of CSR activities and the firms’ incentives to invest in CSR. Recall that the degree of substitutability \(\gamma \) is considered as a measure of the intensity of competition between the firms where a higher value of \(\gamma \) indicates a higher degree of competition between the two firms. The level of CSR spillovers is seen as a measure of the appropriability of the outcomes of the CSR efforts where a higher \(\theta \) indicates that CSR is not specific to the CSR leader.

It seems intuitive that for a low level of CSR spillovers, i.e., investments in CSR are highly firm-specific and are hard to imitate, the CSR leader has a higher incentive to invest and, consequently, the CSR leader will select a higher level of CSR and obtain higher profits. The reason is that the leader can use CSR investments as a sort of commitment device and manipulate the demand for its product to obtain a strategic advantage. As the situation without spillovers is a natural starting point, I first consider the case \(\theta =0\) as a benchmark case. Subsequently, I will discuss the influence of CSR spillovers in more detail.

5.1 The benchmark case of no CSR spillovers

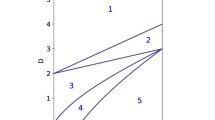

If there are no spillovers, i.e., \(\theta =0\), using the equilibrium investments in (5) and (6), it is easy to see that \(s_{1}^{*} -s_{2}^{*}=\frac{\gamma ^{2}(2+\gamma )}{(1+\gamma )(3-\gamma ^{2} )(6-\gamma (4+\gamma (5-\gamma -\gamma ^{2})))}s_{1}^{*}>0\) for \(0<\gamma \le \gamma _{\max }\). The CSR leader selects a higher level of CSR to increase the differentiation advantage if products are imperfect substitutes. Furthermore, in this benchmark case, we have \(\partial s_{1}^{*} /\partial \gamma <0\) for \(\gamma <0.531963\) and \(\partial s_{1}^{*} /\partial \gamma >0\) for \(0.531963<\gamma <\gamma _{\max }\). In contrast to this, for the follower we obtain \(\partial s_{2}^{*}/\partial \gamma <0\) for \(0<\gamma <\gamma _{\max }\). In Fig. 1, the equilibrium levels of CSR investments of the leader and the follower in the situation of no CSR spillovers (\(\theta =0\)) are depicted.Footnote 9

Influence of the level of competition (degree of substitutability) on CSR investments with no CSR spillovers \((\theta =0)\). For increasing intensity of competition, the CSR leader’s investment first decreases, but then increases (bold curve). In contrast, the CSR follower’s investment decreases throughout (dashed curve). Note that the difference between CSR engagements increases for increasing levels of competition. In the figure, \(a=1,c=0\)

Figure 1 depicts this difference in the qualitative properties of the firms’ CSR investments for increasing degrees of competition. The follower’s level of CSR investment decreases with increasing product substitutability, while the leader’s CSR level first decreases until \(\gamma \approx 0.5319\), but then starts to increase.Footnote 10 The maximum equilibrium level of the leader’s CSR investment is reached for \(\gamma =\gamma _{\max }\).

Intuitively, the firm’s incentive to invest in CSR is determined by two effects. On the one hand, for both firms increasing the degree of competition has a negative effect on the markups (prices minus marginal costs) in the product market equilibrium. Consequently, this has a negative effect on the incentives to engage in CSR. On the other hand, CSR has a positive effect on demand (\(\partial x_{i}/\partial s_{i}>0\)) and in the case of no CSR spillovers, we have \(\partial (\partial x_{i}/\partial s_{i} )/\partial \gamma >0\). That is, a higher degree of competition increases the positive demand effect of CSR activity and this results in a positive effect of competition on the incentives to engage in CSR. These two opposite effects contribute to both firms’ incentive to engage in CSR. Looking at the combined impact of these two effects on the CSR leader, we can see that \(\partial \pi _{1}/\partial s_{1}>0\). For small degrees of competition, we then have \(\partial (\partial \pi _{1}/\partial s_{1})/\partial \gamma <0\) (the negative markup effect dominates), whereas for higher competition levels \(\partial (\partial \pi _{1}/\partial s_{1})/\partial \gamma >0\) (the positive demand effect dominates).Footnote 11 This already indicates that there is a U-shaped relation between the CSR engagement and the intensity of competition for the leader. For the CSR follower it can be shown that \(\partial (\partial \pi _{2}/\partial s_{2})/\partial \gamma <0\).Footnote 12 If the firms would select their levels of CSR simultaneously, these two effects would determine the overall outcome. However, in the present setup the CSR leader can commit to a high level of CSR and by acting tough can induce a lower CSR engagement of the follower.Footnote 13 Hence, the CSR leader’s incentive is determined by the direct effect described above and an additional positive strategic effect.Footnote 14 As a consequence, there is an incentive for the CSR leader to “overinvest” in CSR activities, which leads to \(s_{1}>s_{2}\). Additionally, a higher degree of competition makes the strategic effect even more pronounced, leading to an increase in the difference between the CSR engagements for increasing degrees of competition. Overall, the interplay between the markup effect, the demand effect, and the strategic effect determine the incentives of the CSR leader and CSR follower to engage in CSR and, consequently, the observed pattern of CSR activities.

It is not surprising that as a result of the higher CSR engagement, the leader’s profit is higher than the follower’s profit. To put it differently, the CSR leader has a first-mover advantage. What is interesting, however, is that the first-mover advantage gets more pronounced for increasing degrees of competition. In other words, as the products become increasingly homogeneous, the CSR leader increases its engagement in CSR and, as a consequence, the leader’s profit advantage can not only be sustained, but made even larger. We can now summarize the results obtained so far as follows. The proof of the lemma follows from a simple comparison is therefore omitted.

Lemma 1

In an industry where the outcomes of the CSR investments are highly specific to the leader, i.e., there are no CSR spillovers (\(\uptheta =0\)), a CSR leader invests more than a CSR follower, \(s_{1}^{*}>s_{2}^{*}\). Furthermore, the CSR leader has a first-mover advantage, that is the leader obtains a higher profit than the CSR follower, \(\pi _{1}^{*}>\pi _{2}^{*}\).

5.2 The case with positive CSR spillovers

How do the firms’ CSR investments change if the leader’s CSR activities cannot be protected and also benefit the CSR follower? On an intuitive level, we might expect that CSR spillovers dampen the incentives of the leader to engage in CSR. Furthermore, as a consequence, the CSR leader might even lose its first-mover advantage. In fact, if we consider the influence of increasing spillover levels on the incentives to engage in CSR, we notice an asymmetry between the leader and the follower, which is obviously due to the (assumed, but plausible) asymmetric directions of spillovers. We have \(\partial (\partial \pi _{1}/\partial s_{1})/\partial \theta <0\) for the leader, but \(\partial (\partial \pi _{2}/\partial s_{2})/\partial \theta >0\) for the follower. Accordingly, as expected, increasing levels of CSR spillovers dampen the leaders’ incentives to engage in CSR, but enhance the incentives of the CSR follower.

Figure 2 provides a more detailed picture of the situation with positive CSR spillovers. The bold curve in the figure represents the location of the contour where \(\pi _{1}^{*}=\pi _{2}^{*}\). For a given degree of substitutability between the products, if CSR spillovers \(\theta \) are quite small (i.e., \(\theta \) is below the bold curve depicted in Fig. 2), then the CSR leader achieves higher profits (\(\pi _{1}^{*}>\pi _{2}^{*}\)). Hence, in this region a first-mover advantage for the leader emerges. It is interesting to notice that a first-mover advantage only occurs if the level of appropriability is very low. Otherwise, the second-mover achieves higher profits. Figure 2 also depicts the region where the leader’s CSR investments are higher than the follower’s (\(s_{1}^{*}>s_{2}^{*}\) in the region above the dashed curve and \(s_{1}^{*}<s_{2}^{*}\) below). Again, it can be noted that this region is rather small, meaning that the existence of CSR spillovers drastically reduces the incentives for the CSR leader to engage heavily in CSR. This gives rise to my second result on the sustainability of a first-mover advantage (FMA) and the influence of CSR spillovers. The proof follows again immediately from the arguments above and a simple comparison of profits and CSR investments.

Lemma 2

A CSR leader achieves a FMA only if the outcomes of the CSR efforts are highly specific to the leader, that is the level of CSR spillovers \(\theta \) is quite small. Otherwise, the CSR follower has a second-mover advantage, \(\pi _{1}^{*}<\pi _{2}^{*}\). Moreover, the CSR leader selects a higher activity level of CSR than the CSR follower if the outcomes of the CSR efforts are highly specific to the firm, i.e., if CSR spillovers are quite small (independent of the degree of competition). Otherwise, the CSR follower has a higher level of CSR activity, \(s_{1}^{*}<s_{2}^{*}\).

Influence of the level of competition \(\gamma \) (substitutability of the products) and CSR spillovers \(\theta \) on the competitive advantage and CSR investments. The curve where \({{\pi }{^{*}_{1}}} = {{\pi }{^{*}_{2}}}\) is drawn in bold, the curve where \({s}_1^{*} = {\varvec{s}}_{2}^{*}\) is drawn dashed. Below the bold curve, the CSR leader achieves a first-mover advantage. In the figure, \(a=1,c=0 \)

Finally, let us consider how the qualitative investment patterns change if CSR spillovers exist. As argued above, the higher the level of CSR spillovers, the lower the incentives of the CSR leader to engage in CSR. The result is that the increasing part of the graph of the leader’s CSR activity level shown in Fig. 2 is getting smaller until eventually the leader’s level of CSR activities is decreasing everywhere for \(\theta >0.229499\). Recall that CSR spillovers have the opposite effect on the follower’s incentive to engage in CSR. What we see for our CSR game is that if the spillover level is sufficiently large (\(\theta >0.202167\)), then starting from a monopoly situation (\(\gamma =0\)) the CSR follower’s investment first decreases for increasing levels of competition, but then starts to increase for sufficiently high competition levels. Again, this observation illustrates that the incentives to engage in CSR is asymmetric between CSR leader and CSR follower and strongly depend on the appropriability of CSR. As this analysis demonstrates, if the degree of appropriability is sufficiently high, the CSR leader and the CSR follower switch roles in the sense that the follower has a higher activity level of CSR and obtains a higher profit than the leader who selects the level of CSR first.

It is interesting to notice that there are intermediate levels of competition where qualitatively the investment patterns of the CSR leader and CSR follower are identical. Figure 3 illustrates such a situation for \(\theta =0.21\). Summarizing, the following result on the CSR leader’s and CSR follower’s investments can be given which holds for \(a>c\).Footnote 15

Lemma 3

For sufficiently low levels of CSR spillovers (\(\theta <0.202167\)), the CSR follower’s investment in equilibrium decreases for increasing intensity of competition, whereas the CSR leaders’ investment first decreases, but then increases again. If spillovers are sufficiently large (\(\theta >0.229499\)), then CSR leader’s investment is monotonically decreasing and the CSR follower’s investment is U-shaped.

The proof of the lemma is based on numerical analysis. Given the leader’s and follower’s investment patterns in the benchmark case of no spillovers (see Fig. 1), one can check the sign of the derivatives \(\partial s_{1}^{*}/\partial \gamma \) and \(\partial s_{2}^{*}/\partial \gamma \) evaluated at \(\gamma =\gamma _{\max }\) and calculate the value for which this derivative changes its sign. It can be concluded that \(\partial s_{1}^{*} /\partial \gamma <0\) for \(0<\gamma <\gamma _{\max }\) if \(\theta >0.229499\) and \(\partial s_{2}^{*}/\partial \gamma <0\) for \(0<\gamma <\gamma _{\max }\) if \(\theta <0.202167\).

Influence of competition (degree of substitutability) on the CSR investments CSR spillovers exist. In the figure, I have chosen \(\theta = 0.21\). For increasing intensity of competition, the CSR investments of both firms are U-shaped. Note that the CSR follower’s investments (dashed curve) are higher than the CSR leader’s investment (bold curve). In the figure, \(a=1, c=0 \)

6 Discussion and conclusions

In this paper, I introduce a formal model of CSR leadership to discuss the role of CSR spillovers on a firm’s incentive to invest in CSR prior to other firms. My study demonstrates that only in the rare situations where the outcomes of CSR initiatives are highly specific to a firm (i.e., CSR spillovers are quite low), a first-mover advantage exists and the CSR leader obtains a higher profit than the follower. My study provides support for the claims in conceptual papers like Tetrault Sirsly and Lamertz (2008), Burke and Logsdon (1996), and Reinhardt (1998) who argue that it seems rather difficult to sustain a first-mover advantage based on investments in CSR. It also gives substance to the critical assessment of Vogel (2005), who points out that for most firms socially responsible investments do not pay off since these investments cannot be protected from imitation. This is particularly true if—due to the fear of negative reputation spillovers—the CSR leader might find it appropriate to support the CSR follower on state-of-the-art CSR practices. Although such a behavior might be also based on strategic considerations, it leads to convergence in CSR practices and makes it impossible for the CSR leader to profit from its leadership.Footnote 16 The managerial implication from my work is that the relationship between the intensity of competition and the level of CSR investments and resulting profits might be ambiguous for firms. The particular pattern of investments and profits is highly dependent on industry characteristics (here the degree of substitutability between products) and firm characteristics (being a leader or a follower and the specificity of the outcomes of the CSR efforts). Hence, management has to aim for a good match between particular constellations of industry/firm properties and investments in CSR.

Several extensions of the present model are possible. First, a quite straightforward extension would be to consider multiple leaders and multiple followers in an industry. Here the question might be how CSR spillovers occur (between leaders, or between leaders and followers only?) and how this affects CSR investment behavior. Second, in my paper the leader–follower structure is exogenously given. It would be of interest if such a timing of CSR investments could arise endogenously (e.g., Kopel and Löffler 2012). Third, in my analysis I assume that firms are entrepreneurial. That is, the firm owners select the CSR levels in order to maximize profits. However, what happens if entrepreneurial firms are replaced by managerial firms, where the decision maker has a preference for socially responsible actions? This would be an extension along the lines suggested by Baron (2001), Fisman et al. (2005), Fisman et al. (2006), and Baron (2008). Fourth, what happens in a mixed oligopoly, where only some firms invest in CSR, but others do not? Fifth, how do these results change if CSR efforts change the slope of the demand curve and not only the intercept? Sixth and importantly, most existing work is done in static environments. However, investments in CSR seem to have an inherent dynamic character leaving plenty of room for future research along the lines suggested in Bischi et al. (2010), Bischi et al. (2015), Kopel et al. (2014), and Kopel and Lamantia (2018).

Notes

It is also related to the literature on cost-reducing investment in innovation in the presence of spillovers. Starting from dynamic (multi-stage) settings like the present paper, the analysis of R&D under spillovers has been extended to fully dynamic models of R&D networks (e.g., Bischi and Lamantia 2012a, b; Bischi et al. 2015) and R&D models with knowledge accumulation (Bischi and Lamantia 2011). To my knowledge, no such analysis exists for situations with CSR spillovers.

For the purpose of this paper, I focus on positive spillovers, although in principle spillovers can also be negative; see, e.g., Bertels and Peloza (2008), Yu and Lester (2008), Klein and Dawar (2004). For example, an oil spill might affect the whole oil industry negatively, and perceived failure of a product can induce negative spillovers on a competitor’s product.

See, e.g., Manasakis (2018). As an alternative, one could imagine that investments in CSR alter the slope of the demands; see Sutton (1996) and Symeonidis (1999), Symeonidis (2000), Symeonidis (2003) for vertical differentiation models and Von der Fehr and Stevik (1998) for advertising. The advantage of the present model is that it allows closed-form solutions for a leader–follower timing, whereas this is not the case for the alternative models.

“Specificity refers to the firm’s ability to capture or internalize the benefits of a CSR programme, rather than simply creating collective goods which can be shared by others in the industry, community or society at large.” (Burke and Logsdon 1996, p. 497). As an example for benefits which are highly specific, think of a firm which—instead of air conditioning—uses water from a nearby lake to keep its offices cool and comfortable. This not only serves the environment, but also the firm which can strategically communicate these activities to stakeholders; see Tetrault Sirsly and Lamertz (2008). Further examples can be found in Heslin and Ochoa (2008).

Reinhardt (1998) presents several case studies. For example, Patagonia, a producer of sportswear and outdoor clothing is quite successful in differentiating its products and defending its advantage in a premium-segment of the market. On the other hand, when StarKist Seafood Company announced a switch to a dolphin-safe procurement policy, its main competitors imitated this policy almost immediately.

The denominator of this expression for the leader’s optimal level of CSR involves the second-order condition and it is easy to see that this condition is fulfilled if \(\gamma <\gamma _{\max }\) for all degrees of spillovers. Furthermore, the equilibrium CSR level is also positive.

In all the figures in this section, \(a-c=1\).

The sign is determined by a polynomial of the form \(a_{0}(\gamma ,a-c)+a_{1}(\gamma )s_{1}+a_{2}(\gamma )s_{2}\), where \(a_{0}<0,a_{1}>0\), and \(a_{2}<0\). The relative magnitude of the coefficients and the fact that \(s_{1}>s_{2}\) then give the observed result.

The sign is determined by a polynomial of the form \(a_{0}(\gamma ,a-c)+a_{2} (\gamma )s_{1}+a_{1}(\gamma )s_{2}\), with the same coefficients as for the CSR leader.

Note that \(ds_{2}^{*}/ds_{1}<0\) as long as \(\theta <\gamma /(2-\gamma ^{2})\).

The strategic effect is determined by \(\frac{\partial \pi _{1}}{\partial s_{2}}\frac{\partial s_{2} }{\partial s_{1}}>0\).

The proof is based on numerical analysis. Given the leader’s and follower’s investment patterns in the benchmark case of no spillovers (see Fig. 1), I have checked the sign of the derivatives \(\partial s_{1}^{*}/\partial \gamma \) and \(\partial s_{2}^{*}/\partial \gamma \) evaluated at \(\gamma =\gamma _{\max }\) and calculated the value for which this derivative changes its sign. I conclude that \(\partial s_{1}^{*}/\partial \gamma <0\) for \(0<\gamma <\gamma _{\max }\) if \(\theta >0.229499\) and \(\partial s_{2}^{*}/\partial \gamma <0\) for \(0<\gamma <\gamma _{\max }\) if \(\theta <0.202167\).

Misani (2010) introduces the terms “divergent CSR” and “convergent CSR.” Although both relate to behavior based on strategic considerations, divergent CSR tries to achieve a competitive advantage through differentiation, whereas convergent CSR tries to avoid shared risks or to defend the reputation of their industry by cooperating with competitors.

References

Arya, A., Mittendorf, B.: The changing face of distribution channels: partial forward integration and strategic investments. Prod. Oper. Manag. 22(5), 1077–1088 (2013)

Bagnoli, M., Watts, S.G.: Selling to socially responsible consumers: competition and the private provision of public goods. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 12(3), 419–445 (2003)

Bansal, P., Hunter, T.: Strategic explanations for the early adoption of ISO 14001. J. Bus. Ethics 46, 289–299 (2003)

Baron, D.P.: Private politics, corporate social responsibility, and integrated strategy. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 10(1), 7–45 (2001)

Baron, D.P.: Managerial contracting and corporate social responsibility. J. Public Econ. 92, 268–288 (2008)

Bénabou, R., Tirole, J.: Individual and corporate social responsibility. Economica 77, 1–19 (2010)

Bertels, S., Peloza, J.: Running just to stand still? Managing CSR reputation in an era of ratcheting expectations. Corp. Reput. Rev. 11(1), 56–72 (2008)

Bischi, G.I., Chiarella, C., Kopel, M., Szidarovszky, F.: Nonlinear Oligopolies: Stability and Bifurcations. Springer, Berlin (2010)

Bischi, G.I., Lamantia, F.: Knowledge Accumulation in an R&D network. In: Puu, T., Panchuk, A. (eds.) Nonlinear Economic Dynamics, pp. 209–224. Springer, Berlin (2011)

Bischi, G.I., Lamantia, F.: A dynamic model of oligopoly with R&D externalities along networks. Part I. Math. Comput. Simul. 84, 51–65 (2012a)

Bischi, G.I., Lamantia, F.: A dynamic model of oligopoly with R&D externalities along networks. Part II. Math. Comput. Simul. 84, 66–82 (2012b)

Bischi, G.I., Lamantia, F.: R&D Networks. In: Commendatore, P., Kayam, S., Kubin, I. (eds.) Complexity and Geographical Economics, Topics and Tools, pp. 277–299. Springer, Berlin (2015)

Bischi, G.I., Lamantia, F., Radi, D.: An evolutionary Cournot model with limited market knowledge. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 116, 219–238 (2015)

Brammer, S., Millington, A.: Does it pay to be different? An analysis of the relationship between corporate social and financial performance. Strat. Manag. J. 29, 1325–1343 (2008)

Burke, L., Logsdon, J.M.: How corporate social responsibility pays off. Long Range Plan. 29(4), 495–502 (1996)

Chen, C.: Design for the environment: a quality-based model for green product development. Manage. Sci. 47(2), 250–263 (2001)

Chen, Y.-H., Wen, X.-W., Luo, M.-Z.: Corporate social responsibility spillover and competition effects on the food industry. Aust. Econ. Pap. 55(1), 1–13 (2016)

Dixit, A.: A model of duopoly suggesting a theory of entry barriers. Bell J. Econ. 10(1), 20–32 (1979)

Economist: Do it right.: corporate responsibility is largely a matter of enlightened self-interest, 17 Jan 2008 (2008)

Fernández-Kranz, D., Santalo, J.: When necessity becomes a virtue: the effect of product market competition on corporate social responsibility. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 19(2), 453–487 (2010)

Fisman, R., Heal, G., Nair, V.B.: Corporate social responsibility: doing well by doing good? Working Paper, The Wharton School (2005)

Fisman, R., Heal, G., Nair, V.B. A Model of corporate philanthropy, Working Paper (2006)

Garcia-Gallego, A., Georgantzis, N.: Market effects in consumer’s social responsibility. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 18(1), 235–262 (2009)

Garella, P.G., Petrakis, E.: Minimum quality standards and consumer’s information. Econ. Theor. 36, 283–302 (2008)

Godfrey, P.C., Merrill, C.B., Hansen, J.M.: The relationship between corporate social responsibility and shareholder value: an empirical test of the risk management hypothesis. Strateg. Manag. J. 30, 425–445 (2009)

Häckner, J.: A note on price and quantity competition in differentiated oligopolies. J. Econ. Theory 93, 233–239 (2000)

Harjoto, M.A., Jo, H.: Corporate governance and CSR Nexus. J. Bus. Ethics 100, 45–67 (2011)

Heslin, P.A., Ochoa, J.D.: Understanding and developing strategic corporate social responsibility. Organ. Dyn. 37(2), 125–144 (2008)

Husted, B.W., de Jesus Salazar, J.: Taking Friedman seriously: maximizing profits and social performance. J. Manage. Stud. 43(1), 75–91 (2006)

Kanniainen, V., Pietarila, E.: Corporate social responsibility: can markets control? Discussion Paper No 138, HEER (2006)

Kitzmueller, M., Shimshack, J.: Economic perspectives on corporate social responsibility. J. Econ. Lit. 50(1), 51–84 (2012)

Klein, J., Dawar, N.: Corporate social responsibility and consumers’ attributions and brand evaluations in a product-harm crisis. Int. J. Res. Mark. 21, 203–217 (2004)

Kopel, M., Lamantia, F.: The persistence of social strategies under increasing competitive pressure. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 91, 71–83 (2018)

Kopel, M., Lamantia, F., Szidarovszky, F.: Evolutionary competition in a mixed market with socially concerned firms. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 48, 394–409 (2014)

Kopel, M., Löffler, C.: Commitment, first-mover, and second-mover advantage. J. Econ. 94(2), 143–166 (2008)

Kopel, M., Löffler, C.: Organizational governance, leadership, and the influence of competition. J. Inst. Theor. Econ. (JITE) 168(3), 362–392 (2012)

Lieberman, M.B., Montgomery, D.B.: First-mover advantages. Strateg. Manag. J. 9, 41–58 (1988)

Lieberman, M.B., Montgomery, D.B.: First-mover (dis)advantages: retrospective and link with the resource-based view. Strateg. Manag. J. 19, 1111–1125 (1998)

Liu, C.-C., Wang, L.F.S., Lee, S.-H.: Strategic environmental corporate social responsibility in a differentiated duopoly market. Econ. Lett. 129, 108–111 (2015)

Lyon, T.P., Maxwell, J.W.: Corporate social responsibility and the environment: a theoretical perspective. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2(2), 240–260 (2008)

Manasakis, C.: Business ethics and corporate social responsibility. Manag. Decis. Econ. 39, 486–497 (2018)

McWilliams, A., Siegel, D.: Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: correlation or misspecification? Strateg. Manag. J. 21, 603–609 (2000)

McWilliams, A., Siegel, D.: Corporate social responsibility: a theory of the firm perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 26(1), 117–127 (2001)

McWilliams, A., Siegel, D., Wright, P.M.: Guest editors introduction—corporate social responsibility: strategic implications. J. Manage. Stud. 43(1), 1–18 (2006)

McWilliams, A., Parhankangas, A., Coupet, J., Welch, E., Barnum, D.T.: Strategic decision making for the triple bottom line. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 25(3), 193–204 (2016)

Misani, N.: The convergence of corporate social responsibility practices. Manag. Res. News 33(7), 734–748 (2010)

Mohr, L.A., Webb, D.J., Harris, K.E.: Do consumers expect companies to be socially responsible? The impact of corporate social responsibility on buying behavior. J. Consum. Aff. 35(1), 45–72 (2001)

Nehrt, C.: Timing and intensity effects of environmental investments. Strateg. Manag. J. 17, 535–547 (1996)

Piga, C.: “Corporate social responsibility: a theory of the firm perspective”—a few comments and some suggested extensions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 27(1), 13–15 (2002)

Reinhardt, F.L.: Environmental product differentiation: implications for corporate strategy. Calif. Manage. Rev. 40(4), 43–73 (1998)

Sacco, D., Schmutzler, A.: Is there a U-shaped relation between competition and investment? Int. J. Ind. Organ. 29, 65–73 (2011)

Schmutzler, A. : The relation between competition and innovation—why is it such a mess? Working Paper No. 176, University of Zurich, Socioeconomic Institute (2007)

Schmutzler, A. : The effects of competition on investment—towards a taxonomy. Working Paper, University of Zurich (2008)

Siegel, D.S., Vitaliano, D.F.: An empirical analysis of the strategic use of corporate social responsibility. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 16(3), 773–792 (2007)

Starks, L.T.: Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility: what do investors care about? What should investors care about? Financ. Rev. 44, 461–468 (2009)

Surroca, J., Tribo, J.A., Waddock, S.: Corporate responsibility and financial performance: the role of intangible resources. Strateg. Manag. J. 31, 463–490 (2010)

Sutton, J.: Technology and market structure. Eur. Econ. Rev. 40, 511–530 (1996)

Symeonidis, G.: Cartel stability in advertising-intensive and R&D-intensive industries. Econ. Lett. 62, 121–129 (1999)

Symeonidis, G.: Price and nonprice competition with endogenous market structure. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 9(1), 53–83 (2000)

Symeonidis, G.: Comparing Cournot and Bertrand equilibria in a differentiated duopoly with product R&D. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 21, 39–55 (2003)

Tetrault Sirsly, C.-A., Lamertz, K.: When does a corporate social responsibility initiative provide a first-mover advantage? Bus. Soc. 47(3), 343–369 (2008)

Tishler, A., Milstein, I.: R&D wars and the effects of innovation on the success and survivability of firms in oligopolistic markets. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 27, 519–531 (2009)

Toolsema, L.A.: Interfirm and Intrafirm switching costs in a vertical differentiation setting: green versus nongreen products. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 18(1), 263–284 (2009)

Vives, X.: Innovation and competitive pressure. J. Ind. Econ. LVI 3, 419–469 (2008)

Vogel, D.: The Market for Virtue. The Potential and Limits of Corporate Social Responsibility, Brookings Institution Press, Washington, DC (2005)

Von der Fehr, N.-H., Stevik, K.: Persuasive advertising and product differentiation. South. Econ. J. 65(1), 113–126 (1998)

Wang, C., Nie, P.-Y., Meng, Y.: Duopoly competition with corporate social responsibility. Aust. Econ. Pap. 57(3), 327–345 (2018)

Yu, T., Lester, R.H.: Moving beyond firm boundaries: a social network perspective on reputation spillover. Corp. Reput. Rev. 11(1), 94–108 (2008)

Acknowledgements

The paper has benefitted from the thoughtful comments and suggestions of two anonymous reviewers.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Graz.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This paper is a revised version of a working paper entitled “Strategic CSR, Spillovers, and First-Mover Advantage” that has been circulated and frequently cited since 2009 (see, e.g., McWilliams et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2018; Chen et al. 2016).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kopel, M. CSR leadership, spillovers, and first-mover advantage. Decisions Econ Finan 44, 489–505 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10203-021-00328-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10203-021-00328-9

Keywords

- First-mover advantage

- Corporate social responsibility

- Intensity of competition

- CSR spillovers

- CSR leadership