Abstract

Background

Chronic anal fissure (CAF) is a painful condition that is unlikely to resolve with conventional conservative management. Previous studies have reported that topical treatment of CAF with glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) reduces pain and promotes healing, but optimal treatment duration is unknown.

Methods

To assess the effect of different treatment durations on CAF, we designed a prospective randomized trial comparing 40 versus 80 days with twice daily topical 0.4% GTN treatment (Rectogesic®, Prostrakan Group). Chronicity was defined by the presence of both morphological (fibrosis, skin tag, exposed sphincter, hypertrophied anal papilla) and time criteria (symptoms present for more than 2 months or pain of less duration but similar episodes in the past). A gravity score (1 = no visible sphincter; 2 = visible sphincter; 3 = visible sphincter and fibrosis) was used at baseline. Fissure healing, the primary endpoint of the study, maximum pain at defecation measured with VAS and maximum anal resting pressure were assessed at baseline and at 14, 28, 40 and 80 days. Data was gathered at the end of the assigned treatment.

Results

Of 188 patients with chronic fissure, 96 were randomized to the 40-day group and 92 to the 80-day group. Patients were well matched for sex, age, VAS and fissure score. There were 34 (19%) patients who did not complete treatment, 18 (10%) because of side effects. Of 154 patients who completed treatment, 90 (58%) had their fissures healed and 105 (68%) were pain free. There was no difference in healing or symptoms between the 40- and the 80-day group. There was no predictor of fissure healing. A low fissure gravity score correlated with increased resolution of pain (P < 0.05) and improvement of VAS score (P < 0.05) on both univariate and multivariate analysis. A lower baseline resting pressure was associated with better pain resolution on univariate analysis (P < 0.01). VAS at defecation and fissure healing significantly improved until 40 days (P < 0.001), while the difference between 40 and 80 days was not significant.

Conclusion

We found no benefits in treating CAF with topical GTN for 80 days compared to 40 days. Fissure healing and VAS improvement continue until 6 weeks of treatment but are unlikely thereafter.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chronic anal fissure (CAF) is characterized by a long duration of symptoms and by pathologic features such as induration, skin tag, exposed sphincter or hypertrophied anal papilla [1]. CAF is unlikely to heal with conventional conservative management such as bulking agents and “sitz baths” and traditional treatment for chronic fissure is surgical sphincterotomy [2]. Incidence of minor incontinence to flatus and liquid stool after surgical sphincterotomy ranges from 8 to 35% [3, 4], and a medical alternative to sphincterotomy is highly desirable.

Previous studies have reported rapid pain relief and success in healing acute and chronic anal fissures using topical nitrates [5, 6]. Acute fissures have a high rate of spontaneous healing; therefore, most of the reports on the use of topical nitrates that followed these initial observations focused on chronic fissures. According to the last Cochrane review, the effect on healing of chronic fissures was marginally better than placebo and a high spontaneous healing rate was observed [7]. In all the examined studies, a long (>6 weeks) duration of symptoms was considered a sufficient inclusion criteria irrespective of fissure appearance. Inclusion of patients with acute-type fissures may be possible and may in part explain the high healing rate observed in placebo-treated patients. In a study by Scholefield et al. [8] when a subset of fissures with more then one pathologic feature of chronicity were analyzed, healing rate with placebo dropped to 24% and difference between nitrates and placebo became significant.

Other potentially relevant factors such as dose of nitrate and treatment duration should also be taken into account. Dose of nitrate appears to influence healing rate: Watson and colleagues suggested that a concentration of at least 0.3% GTN is necessary to provide adequate internal sphincter relaxation and allow healing [9]. In a dose escalating study, optimal GTN concentration for symptomatic relief was 0.4% [10]. No study to date has compared different treatment durations. In a prospective cohort study using topical isosorbide dinitrate Schouten et al. [11] found that fissure healing rate increased with treatment duration. Healing rate was 35% at 6 weeks and 88% at 12 weeks. Higher healing rate at 10 weeks (89%) vs. 5 weeks (67%) is also documented in a randomized trial of sphincterotomy vs. isosorbide dinitrate [12]. Compliance with treatment may become a problem out of trials, however, and a minimum length of time for treatment while maintaining efficacy is desirable. The aim of this study was to observe the effect of duration of treatment with topical GTN on healing of and pain from CAF.

Patients and methods

The study was a prospective randomized open label multicenter trial. Inclusion criteria were any of the following: presence of induration (fibrosis), skin tag, visible internal anal sphincter fibers or hypertrophied anal papilla. In addition to morphological criteria duration of symptoms for more than 2 months [1] or with pain of less duration but similar episodes in the past was required. Exclusion criteria were age <18, nitrate medications, history of orthostatic hypotension, history of recent (<2 months) anal surgery, pregnancy, contraindications or intolerance to nitrates, fissure off-midline, inflammatory bowel disease or fissure secondary to an underlying disease e.g., HIV, tuberculosis, syphilis.

Eleven Coloproctology Units currently registered with the Italian Society of Colorectal Surgery (SICCR) participated in the study. The study received ethical approval by the SICCR Trial Review Board and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All the patients gave written informed consent for participation in the study.

Aluminum tubes containing 0.4% GTN ointment (Rectogesic®, Prostrakan Group) were provided by the Pharmaceutical Company free of charge. Each patient was instructed to squeeze out of the tube 2.5 cm of GTN ointment (a measuring line was printed on the product), which corresponds to approximately 1.5 mg of GTN, and to apply it twice daily with a gloved finger to the distal anal canal. Patients were also encouraged to prevent hard stool with dietary measures and to expect and report specific side effects. Baseline assessment included duration of symptoms, worse pain on a VAS scale at defecation, anal examination with assessment of fibrosis, exposed sphincter and hypertrophic papilla (e). Manometry was performed if tolerated by the patient. Investigators were instructed to record only the maximum resting pressure (MRP) along the anal canal in mmHg using the manometry equipment available in their facility. Technical details on different methods of acquisition of resting pressure were not assessed. Follow-up visits were scheduled at 2, 4, 6 and 8 weeks and 80 days and included assessment of symptoms and compliance, worse pain on a VAS scale at defecation and anal examination. Compliance was based on patient’s report and assessed at each visit. Patients applying the prescribed amount of GTN at least 12 times per week were considered compliant. Fissures were scored 0 to 3 (grade 0 = no fissures; grade 1 = fissure with no visible sphincter or fibrosis; grade 2 = fissure with visible sphincter without fibrosis and grade 3 = fissure with visible sphincter and fibrosis). In monitoring side effects, headache was not graded, and dizziness was defined as either severe light-headedness, severe muscle weakness or orthostatic hypotension.

Patients were randomized to either 40 days (6 weeks) treatment or 80 days (12 weeks) of topical GTN treatment. Calculated sample size was 81 patients per arm based on an expected healing rate of 70% to detect a 20% difference at P < 0.05 level with β set at 0.1 using Pocock’s formula. Taking into account a drop-out rate of 10%, total number of 178 was estimated as sufficient to close the study. Randomization was performed in computer-generated blocks and concealed in opaque sealed envelopes. Participating physicians were not aware of block size.

Statistical analysis

Fissure healing and resolution of evacuatory pain are categorical variables, so we performed a multivariate logistic regression model with stepwise selection of independent variables. Each of the two outcomes was analyzed both by multivariate analysis of data at the end of treatment (according to assigned treatment) and after the crossover of 9 patients by 40-day treatment to 80-day treatment group (according to treatment protocol). All baseline variables are included in the initial model as independent covariates. The significance level for entering in the model was 0.20. Treatment allocation, sex and age were forced to enter the model as adjustment variables even if not statistically significant. The effect of independent variables on the outcomes was measured by odds ratio (OR) estimates and 95% confidence interval (CI).

We used linear mixed models to analyze the temporal variations of pain measured by VAS, the timing of fissure healing and of pain resolution. Linear mixed model allows repeated measures analysis in the presence of missing values, assuming that the values are missing at random. The set of covariates that determined the model with the lowest Akaike Information Criterion were included in the model with observation time point, sex and age. The results were expressed through the mean and standard deviation determined by the least squares estimate.

We also carried out multiple comparisons to assess the difference of VAS, fissure healing and resolution of evacuatory pain between consecutive observation time point; P-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons according to the Tukey–Kramer method.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software Version 9.2 for PC.

Results

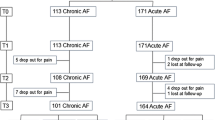

Between March 2007 and November 2008, 188 patients were enrolled, 96 in the 40-day group and 92 in the 80-day group. At baseline, the only characteristic that differed between groups was the presence of skin tags, which were more frequent in the 80-day group (Table 1). There were 2 patients with a painless chronic fissure, both in the 40-day treatment group. Neither of these 2 patients healed their fissure, and one developed mild pain (VAS = 2) in the course of the treatment. Of 188 patients initially enrolled, 34 (19%) either discontinued treatment (n = 27) or were lost to follow-up (n = 7), 21 in the 40-day group and 13 in the 80-day group (P = 0.42). Reasons for discontinuation of treatment were side effects in 15 (8%), worsening symptoms in 9 (5%) and a combination of both in 3 (2%). Headache and dizziness were the only side effects noted (Table 2). A flow chart with the results of the study is shown in Fig. 1.

Healing of fissure

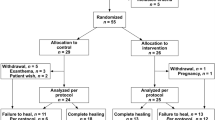

According to the intention to treat and considering drop-outs as failures, 41 (43%) patients had their fissures completely healed in the 40-day group vs. 42 (46%) in the 80-day group (P = 0.77). Of the 154 patients who completed treatment, 41 of 75 (55%) patients in the 40-day group and 42 of 79 (53%) patients in the 80-day group had their fissures healed (P = 0.87). At the end of the 40-day treatment, 9 patients crossed over from the 40- to the 80-day group. By the end of the first 40 days, 3 of 9 crossover patients were free of pain but with a persistent fissure and 6 reported symptomatic improvement from an average VAS of 8.1 (±0.1 SD) to an average VAS of 4.5 (±2 SD). All 9 crossover patients healed their fissure after 80 days of treatment. Results of the univariate analysis for fissure healing in the 154 patients who completed the assigned treatment are shown in Table 3. There was no variable that significantly predicted fissure healing after GTN treatment. Similarly, on multivariate analysis according to assigned treatment and per treatment protocol, no variable was independently predictive of fissure healing.

Resolution of pain

According to intention to treat and considering drop-outs as failures, 43 of 96 (45%) patients in the 40-day group and 53 of 92 (58%) patients in the 80-day group were free of pain at defecation by the end of the study (P = 0.08). After eliminating the 35 who discontinued treatment, there were 43 of 75 (57%) pain-free patients in the 40-day group and 53 of 79 (67%) pain-free patients in the 80-day group (P = 0.24). Including the 9 patients who crossed over from the 40-day group to the 80-day group, a total of 105 (68%) compliant to GTN treatment were free from pain. The results of the univariate analysis for resolution of evacuatory pain according to assigned treatment are shown in Table 4. Persistence of pain was associated with fibrosis (P = 0.018), high maximum resting pressure (P = 0.0128) and high fissure gravity score (P = 0.036).

On multivariate analysis according to assigned treatment, a low fissure gravity score (OR = 0.034, 95% CI 0.004–0.277) was the only independent predictor of pain resolution. When multivariate analysis was carried out according to treatment protocol, treatment assignment to the 80-day group (OR = 2.757, 95% CI 1.147–6.630) and low fissure score (OR = 0.053, 95% CI 0.007–0.401) were independent predictors of pain resolution (Table 5).

Changes in VAS score

Of the 154 patients who completed the study, 150 (97%) had symptomatic improvement as measured by the VAS score. Of the 49 patients with residual pain at the end of the study, 45 improved by a mean of 4.1 points (±1.74 SD) on a VAS scale of 1 to 10. When the linear mixed model was applied to analyze factors significantly correlated with a change of VAS score, an initial fissure gravity score of 1 (estimate = −0.6003; standard error = 0.3000; P = 0.0472) and initial fissure gravity score of 2 (estimate = −1.1806; standard error = 0.2762; P = <0.0001) were significantly correlated with improvement of the VAS score over time. Changes in VAS score during GTN treatment are shown in Fig. 2. VAS score decreased significantly and progressively through the trial until after 6 weeks when no further significant improvement in VAS pain score was observed.

Timing of fissure healing

Healing of fissure over time is illustrated in Fig. 3. Healing increased significantly and progressively through the trial until after 6 weeks when no further significant improvement in numbers of fissures healed was observed.

Timing of pain resolution

Resolution of pain over time is illustrated in Fig. 4. There was a significant increase in the number of patients whose pain resolved between base line and 2 weeks (P < 0.001), 2 weeks and 4 weeks (P < 0.001), 4 weeks and 40 days (P < 0.001) and between 40 days and 80 days (P = 0.007).

Discussion

Our study is the first trial that addresses treatment duration with GTN ointment in chronic anal fissure. Our results show that an 80-day (12 weeks) topical GTN course is not superior to a 40-day (6 weeks) course when healing and pain are taken as endpoints. Our definition of chronic anal fissure was more stringent than any other published study, since it included both anatomic features of chronicity and duration of symptoms. Our overall success rate in healing chronic fissure was of 43% (which includes a 20% drop-out rate). Of the patients who did not complete the study, half of them had unwanted side effects, while the other half had persistent unresolved pain. Among patients who completed the study, fissure healing rate was 58% and a complete symptomatic response was seen in 68%, in line with previous randomized controlled trials [7].

The majority of compliant patients had a consistent and progressive decrease of pain at defecation measured by the VAS. This is reflected in the decrease of VAS from an average of 8 (95% CI 7–10) to an average below 1 (95% CI 0–7) in 150 (97%) of the patients who completed the study (Fig. 2). Ours is the first clinical trial that used the 0.4% concentration of GTN twice daily, which was found to be the most effective in a dose escalating trial [10]. This concentration is also commercially available and therefore easily used out of a trial setting.

The optimal treatment duration for topical GTN was 6 weeks. Ours is the first prospective study monitoring the effects of topical GTN treatment for longer than 8 weeks. Resolution of pain, fissure healing and VAS continue to improve significantly until 6 weeks. If by 6 weeks the fissure has not healed, treatment with GTN ointment should be discontinued, and the patient should be referred to a surgeon for sphincterotomy that has shown to be successful in patients failing GTN treatment [13]. Some reports have shown healing of the fissure after failed GTN treatment with other topical agents [14] or with botox injection [15]. A possible exception to this algorithm may be in patients who have shown considerable improvement after GTN treatment. In our trial, 9 of such patients were allowed to cross over to the 80-day group, and all of them healed their fissure (Fig. 1). This is reflected in the data analysis after crossover that showed the 80-day course to be superior to the 40-day course in obtaining complete symptomatic resolution.

Of the 154 patients who completed the trial, 23% suffered from headache and 2% from dizziness, while of the 34 who discontinued treatment, 44% suffered from headache and 3% from dizziness (Table 1). Our rate of side effects is similar to other studies that used different GTN concentration [9, 10, 16]. If headache or dizziness were present, patients were instructed to apply the ointments while lying down or to take paracetamol before GTN application. Patient counseling on expecting, preventing and treating the possible side effects of topical GTN is an important part of the treatment.

In our multivariate analysis, we found that fissures with a high severity score, which include fissures with both an exposed sphincter and fibrosis, were less likely to have a symptomatic response even after a long course of GTN. A high resting pressure was correlated with persistence of symptoms on univariate analysis, but manometry data was not available in all patients and could not be included in the multiple regression model. Patients with both fibrosis and exposed sphincter (grade 3) were 46% of compliant patients, and 50% of them healed their fissure (Table 3). Therefore, while we think that these patients should be closely monitored and treatment promptly changed after a 6 weeks of GTN, we do not think that GTN should be automatically excluded from their treatment algorithm. This group of patients should be adequately counseled about risk and benefits of various treatment options.

In conclusion, the treatment response of CAF to topical GTN continues to improve until 6 weeks after which there is no additional benefit observed. Fissures with both fibrosis and exposed sphincter fibers are less likely to respond to GTN treatment. This should be taken into account when counseling patients with CAF.

References

Lund JN, Scholefield JH (1996) Aetiology and treatment of anal fissure. Br J Surg 83:1335–1344

Fleshman JW (1993) Anorectal motor physiology and pathophysiology. Surg Clin North Am 73:245–265

Pernikoff BJ, Eisenstat TE, Rubin RJ, Oliver GC, Salvati EP (1994) Reappraisal of partial lateral internal sphincterotomy. Dis Colon Rectum 37:1291–1295

Khubchandani I, Reed J (1989) Sequelae of internal sphincterotomy for chronic fissure in ano. Br J Surg 76:431–434

Gorfine SR (1995) Treatment of benign anal disease with topical nitroglycerin. Dis Colon Rectum 38:453–457

Gorfine S (1995) Topical nitroglycerine therapy for anal fissures and ulcers. N Engl J Med 333:1156–1157

Nelson R (2006) Non surgical therapy for anal fissure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4:CD003431

Scholefield JH, Bock JU, Marla B et al (2003) A dose finding study with 0.1%, 0.2%, and 0.4% glyceryl trinitrate ointment in patients with chronic anal fissures. Gut 52:264–269

Watson SJ, Kamm MA, Nicholls RJ, Phillips RK (1996) Topical glyceryl trinitrate in the treatment of chronic anal fissure. Br J Surg 83:771–775

Bailey HR, Beck DE, Billingham RP et al (2002) A study to determine the nitroglycerin ointment dose and dosing interval that best promote the healing of chronic anal fissures. Dis Colon Rectum 45:1192–1199

Schouten WR, Briel JW, Boerma MO, Auwerda JJA, Wilms EB, Graatsma BH (1996) Pathophysiological aspects and clinical outcome of intra-anal application of isosorbide dinitrate in patients with chronic anal fissure. Gut 39:465–469

Parellada C (2004) Randomized, prospective trial comparing 0.2 percent isosorbide dinitrate ointment with sphincterotomy in treatment of chronic anal fissure: a two-year follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum 47:437–443

Evans J, Luck A, Hewett P (2001) Glyceryl trinitrate vs. lateral sphincterotomy for chronic anal fissure: prospective, randomized trial. Dis Colon Rectum 44:93–97

Jonas M, Speake W, Scholefield JH (2002) Diltiazem heals glyceryl trinitrate-resistant chronic anal fissures: a prospective study. Dis Colon Rectum 45:1091–1095

Lindsey I, Jones OM, Cunningham C, George BD, Mortensen NJ (2003) Botulinum toxin as second-line therapy for chronic anal fissure failing 0.2 percent glyceryl trinitrate. Dis Colon Rectum 46:361–366

De Nardi P, Ortolano E, Radaelli G, Staudacher C (2006) Comparison of glycerine trinitrate and botulinum toxin-A for the treatment of chronic anal fissure: long-term results. Dis Colon Rectum 49:427–432

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Marina Fiorino for her invaluable assistance with the trial administration, Prof. Mario Pescatori, Prof. Rudolph Schouten and the late Dr. Richard Tonge for their support and input in conceiving the study, Dr. Nicola Bartolomeo of the University of Bari for statistical support and Mr. Jonathan Lund for critical reading of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Gagliardi, G., Pascariello, A., Altomare, D.F. et al. Optimal treatment duration of glyceryl trinitrate for chronic anal fissure: results of a prospective randomized multicenter trial. Tech Coloproctol 14, 241–248 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-010-0604-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-010-0604-1