Abstract

Background

Ferguson hemorrhoidectomy is believed to result in less postoperative pain because of a closed wound. Stapled hemorrhoidopexy, without a perianal wound, should thus have lesser pain. We conducted a prospective randomized trial to compare stapled hemorrhoidopexy (SH) with Ferguson hemorrhoidectomy (FH).

Methods

Fifty patients with third-degree or early fourthdegree hemorrhoids who required surgery were recruited. Patients were prospectively randomized to receive either FH or SH. Data collected include operative time, hospital stay, fecal incontinence and pain scores, morbidity and complications.

Results

SH patients had less pain in the early postoperative period. There were no significant differences in hospital stay or major complications. One patient after SH required emergency reintervention for thrombosed hemorrhoids distal to the staple line. FH patients had more minor problems of bleeding, wound discharge and pruritus. Fecal incontinence was similar in the 2 groups but two of the three patients with daily incontinence to gas after SH claimed that their lifestyle was affected.

Conclusions

SH is safe to perform and results in less postoperative pain as well as less minor morbidity. Early reintervention and incontinence to gas compromising lifestyle occurred only after SH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Stapled hemorrhoidopexy (SH) is becoming more popular in the surgical treatment of prolapsed hemorrhoids. Over the last few years, there has been an increasing number of randomized controlled trials comparing SH with open, namely Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy [1–6]. These have consistently shown SH to be less painful than open hemorrhoidectomy in the postoperative period. The benefits of shorter operating time, hospital stay and earlier return to work are less certain. Some papers did not report on these issues or reported no difference between the two techniques.

However, in many other parts of the world, closed rather than open hemorrhoidectomy is the technique of choice. Closed, namely Ferguson, hemorrhoidectomy (FH) was designed to leave a less painful perianal wound. Nonetheless, randomized controlled trials have reported conflicting results as to whether closed hemorrhoidectomy provided less pain and more rapid wound healing compared to the open technique [7–10]. This may be due to a variable incidence in wound dehiscence after closed hemorrhoidectomy, which leads to prolonged healing and more pain.

If the closed perianal wound after closed hemorrhoidectomy results in less pain, it should stand that SH with no perianal wound would be only minimally better than closed hemorrhoidectomy. However, there has only been one randomized trial comparing closed hemorrhoidectomy with SH [11]. We therefore performed a randomized controlled clinical trial to compare SH with FH directly. The end points compared were operative time, complications, pain and wound healing.

Patients and methods

The Singapore General hospital’s ethics committee approved the research protocol. A total of 50 consecutive patients with either third-degree or early fourth-degree hemorrhoids (prolapsed irreducible piles or piles which re-prolapsed repeatedly soon after manual reduction) were recruited and provided informed consent. Exclusion criteria were patients with acute thrombosed internal piles, previous hemorrhoidectomy, anal strictures, fecal incontinence and medical conditions that made the patient unfit for elective surgery. Complete colonoscopies were performed in patients over the age of 50 years, those with a family history of colorectal cancer and those with other gastrointestinal symptoms. All other patients had a rigid sigmoidoscopy at the time of surgery. Patients were allocated to either FH or SH groups by computer randomization.

Surgical technique

All operations were performed under general anesthesia, with the patient in the supine lithotomy position, by the same specialist consultant surgeon (YHH). In FH patients, a standardized closed hemorrhoidectomy was done through an Eisenhammer anal retractor [7, 12]. Hemorrhoids were excised to the anorectal junction with diathermy, with adequate preservation of the intervening skin and anoderm bridges. The base of the pedicle was transfixed with 2/0 polyglactin. The edges of the hemorrhoidectomy wound in the anoderm and skin were apposed with continuous polyglactin. Three hemorrhoids were excised in all patients, but small intervening secondary hemorrhoids were left alone to fibrose. No packs were left in the anus postoperatively.

In the SH group, a standardized SH was performed according to the technique previously described [1, 13]. Briefly, an Eisenhammer retractor was used to insert a 2/0 propylene pursestring suture, taking submucosal bites of the lower rectum, at least 2 cm above the dentate line. A Premium CEEA 34 plus (curved end-to-end anastomosis) intraluminal stapler (Tyco Healthcare) was opened and its distal anvil was inserted beyond the purse-string suture. The later was firmly tied into a specially designed proximal groove in the stem of the anvil. This enabled more mucosa to be pulled into the shoulder of the circular stapler and result in a larger donut being excised. After firing and removal of the stapler, hemostasis along the staple line was achieved by light diathermy as required.

After operation, patients in both groups were prescribed fiber supplements and naproxen sodium 550-mg tablets or intramuscular pethedine (1 mg per kilogram body weight) as required. FH patients were also advised to gently shower their perianal wounds with lukewarm water twice daily, and after bowel movements. Patients without complications were offered hospital discharge on the day of surgery, but could elect to stay overnight if apprehensive about wound care. Patients who were discharged on the same day of the surgery were considered to have stayed one day.

Data collection

Data recorded include age, sex, duration and nature of symptoms, degree of prolapse, duration of hospitalization, operative time, pain score and complications after surgery. Minor bleeding was defined as symptomatic bleeding for which the patient did not seek medical attention.

Two weeks after discharge, the patients were reviewed clinically. In particular, gentle rectal examinations were performed on SH patients to assess for anorectal strictures. This procedure had previously been reported in our experience to be painless at this time [1]. Blinded observers also reassessed the pain score and analgesic requirements. Eight weeks after surgery, assessment consisted of clinical review, continence scoring, anorectal manometry and a quality of life questionnaire. Fecal continence scoring was performed using a previously described and well-accepted system [14]. Anorectal manometry was performed as described previously [15], using a microcapillary perfusion system (Synectics, Stockholm, Sweden). The validated Eypasch Gastrointestinal Quality of Life instrument was used to assess quality of life [16]. Pain scores were charted by the patients on a 0 to 10 visual analog scale [17].

Results are stated as mean and standard error of mean (SEM) or percentages, unless otherwise indicated. Statistical analyses were performed using chi-square and Mann-Whitney U tests. This was done using SPSS (Chicago, Illinois) version 10 on a personal computer.

Results

A total of 50 patients with third-degree or early fourth-degree hemorrhoids were randomized to stapled hemorrhoidopexy (SH) or closed Ferguson’s hemorrhoidectomy (FH). There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of sex, age, symptoms or extent of prolapse (Table 1). Bleeding was the most common complaint, followed by symptomatic prolapse.

During hospitalization, 1 SH patient (3.4%) had thrombosis of the hemorrhoidal tissue distal to the staple line, causing severe pain and requiring surgical excision. Following discharge, 4 FH patients (19.0%) and 5 SH patients (17.2%) were re-admitted to hospital. Re-admissions were related to wound care problems due to communication difficulties in 2 FH (9.5%) and 2 SH (7.4%) patients. In the remaining 2 FH (9.5%) and 3 SH (10.3%) patients, the re-admissions were for minor wound bleeding. These patients were treated expectantly, and none required surgical intervention or blood transfusion. There were no statistically significant differences in the re-admissions and related complications between the 2 groups.

Postoperative symptoms and complications are shown in Table 2. Significantly more FH patients were troubled by minor rectal bleeding at 2 weeks, although these rates were similar at 8 weeks. In addition, more FH patients had wound discharge at 2 weeks, although again, this difference was no longer significant at 8 weeks. More FH patients had wound pruritis at 8 weeks, even though there was no significant difference at 2 weeks. There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of patient-perceived residual skin tags. The wounds had remained incompletely healed in one patient in each group by the end of 8 weeks due to partial suture line dehiscence. Two SH patients (7.4%) had mild flimsy strictures which were easily dilated by digitation at follow-up, without any patient discomfort; these have not recurred. There were no stenoses in the FH group. However, the differences were neither statistically nor clinically significant. At a followup of 8.5±0.2 months (mean±SD), there were no recurrences in either group of patients.

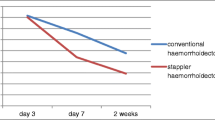

The visual analogue pain score recorded by the patients in the first two weeks after surgery showed a higher pain score for FH patients during postoperpative days 3 to 5 (Table 3). There was a tendency to higher pain scores for FH patients during the first two days and from day 6 onwards, although this did not reach statistical significance. The number of naproxen sodium 550 mg tablets taken during the first two weeks was 22.2±8.7 (mean±SEM) for FH group and 10.0±3.0 SH group. Over the next 6 weeks, the number of naproxen tablets taken was 0.2±0.2 for FH group and 10.0±3.0 for SH group. There was no difference between the two groups in terms of analgesic requirements over the entire 8 weeks.

Patients were scored for incontinence and quality of life 8 weeks after surgery. There was no significant difference in the fecal incontinence severity score (FH, 0.9±0.5; SH, 1.9±1.0). One patient in the SH group had one episode of incontinence to solids, and another had one episode of incontinence to liquids, while there were none in the FH group. None of these patients had persistent incontinence. None of the patients required the use of pads. Both groups had 3 patients each with daily incontinence to gas, and of these patients, two in the SH group claimed that their lifestyle was affected daily after surgery. Anal manometry also showed no significant differences between groups with regard to the mean resting pressures (FH, 36.2±4.3 mmHg; SH, 29.9±3.3) and maximal squeeze pressures (FH, 185.5±26.2 mmHg; SH, 169.3±20.3). At 2 weeks, there was no significant difference in the patients’ satisfaction measured on an analog scale of 0–10 (FH, 7.0±0.9; SH, 6.7±0.7). At 8 weeks, there was also no significant difference in the Eypasch quality of life total scores (FH, 129.1±5.1;SH, 125.9±5.0).

Discussion

We found that patients who underwent stapled hemorrhoidopexy had less pain in the early postoperative period. They also had less minor bleeding, wound discharge problems and pruritus. We previously conducted a randomized clinical trial comparing SH with open diathermy hemorrhoidectomy [1] and found that SH patients had less pain and required less analgesia. Numerous other clinical trials also showed results favoring SH, especially with regards to the extent of postoperative pain [2–6, 18]. In some trials, the duration of hospitalization was shorter after SH [2, 4, 5]. Numerous papers comparing open with closed hemorrhoidectomy have failed to establish the superiority of one over the other procedure [7–10]. Nonetheless, variations in technique such as use of radiofrequency ablation [19], harmonic scalpel [{cx20|20}] for open hemorrhoidectomy and 5–0 absorbable sutures [21] for closed hemorrhoidectomy may have an effect upon the results.

We note that there has only been one randomized clinical trial directly comparing FH with SH [11]. This may be due to the slower take-up rate of the SH technique in the United States, where FH is most commonly practiced. Hetzer et al. [11] from Switzerland reported a randomized trial of 40 patients comparing closed hemorrhoidectomy and stapled hemorrhoidopexy. They showed that SH resulted in shorter operative times, lower pain scores and earlier return to work.

In this study, we demonstrated that FH was associated with higher pain scores on the third to fifth days after surgery. Throughout the two weeks, there was a persistent trend of less pain after SH. We believe that the increased pain was related to stretching of the perianal wound during defecation, which commonly occurred after the second postoperative day. Subsequently, as the closed hemorrhoidectomy wound healed by primary intention, the pain decreased, causing the difference to lose statistical significance later.

We found that the operative time was longer for FH, although this did not reach statistical significance. Likewise, the duration of hospital stay also tended to be longer but was not statistically significant. For the purpose of this study, we did not look at time to return to work nor perform any cost analysis. In our study, we looked at other factors such as minor bleeding, pruritis and residual skin tags; these are not usually mentioned in other studies. We found that FH group had significantly more minor problems such as bleeding, wound discharge and pruritis, up to 8 weeks after surgery. These were symptoms that may seem minor to the surgeon, but may be a significant source of worry and morbidity to the patient. It should be noted, however, that early reintervention and incontinence to gas compromising lifestyle occurred only after SH. A recent meta-analysis comparing SH with hemorrhoidectomy concluded that hemorrhoidectomy remains the “gold standard” of treatment [22]. Alimitation of the present study is the relatively small number of patients, and this could prevent some of the investigated parameters from reaching statistical significance.

In conclusion, we have shown that SH results in less postoperative pain as well as less minor problems. However, the pain after FH was significantly worse than after SH for only a few days after surgery. We believe this was due to stretching of perianal wounds during defecation which may be worse for FH compared to open hemorrhoidectomy. A 3-armed randomized controlled trial involving open, closed and stapled hemorrhoidectomy could be considered to look closer into this issue.

References

Ho YH, Cheong WK, Tsang C et al (2000) Stapled haemorrhoidectomy — cost and effectiveness. Randomized controlled trial including incontinence scoring, anorectal manometry, and endoanal ultrasound assessments at up to three months. Dis Colon Rectum 43:1666–1675

Ganio E, Altomare DF, Gabrielli F et al (2001) Prospective randomized multicentre trial comparing stapled with open haemorrhiodectomy. Br J Surg 88:669–674

Mehigan BJ, Monson JR, Hartley JE (2000) Stapling procedure for haemorrhoids versus Milligan-Morgan haemorrhoidectomy: randomized controlled trial. Lancet 355:782–785

Roswell M, Bello M, Hemingway DM (2000) Circumferential mucosectomy (stapled haemorrhoidectomy) versus conventional haemorrhoidectomy: randomized controlled trial. Lancet 355:779–781

Shalaby R, Desoky A (2001) Randomized clinical trial of stapled versus Milligan-Morgan haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg 88:1049–1053

Ng KH, Eu KW, Ooi BS et al (2003) Stapled haemorrhoidectomy for prolapsed piles performed with concurrent perianal conditions. Tech Coloproctol 7:214–215

Ho YH, Seow-Choen F, Tan M, Leong AF (1997) Randomized controlled trial of open and closed haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg 84:1729–1730

Arbman G, Krook H, Haapaniemi S (2000) Closed vs open haemorrhoidectomy — is there any difference? Dis Colon Rectum 43:31–34

Gencosmanoglu R, Sad O, Koc D, Inceoglu R (2002) Haemorrhoidectomy: open or closed technique? A prospective, randomized clinical trial. Dis Colon Rectum 45:70–75

Hosch SB, Knoefel WT, Pichlmeier U et al (1998) Surgical treatment of piles: prospective, randomized study of Parks vs. Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy. Dis Colon Rectum 41:159–164

Hetzer FH, Demartines N, Handschin AE, Clavien PA (2002) Stapled vs excision hemorrhoidectomy: long-term results of a prospective randomized trial. Arch Surg 137:337–340

Ferguson JA, Heaton JR (1959) Closed hemorrhoidectomy. Dis Colon Rectum 2:176–179

Ho YH, Seow-Choen F, Tsang C, Eu KW (2001) Randomized trial assessing anal sphincter injuries after stapled hemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg 88:1449–1455

Jorge JM, Wexner SD (1993) Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 36:77–97

Ho YH, Tan M (1997) Ambulatory anorectal manometric findings in patients before and after haemorrhoidectomy. Int J Colorectal Dis 12:296–297

Eypasch E, Williams JI, Wood-Dauphinee S et al (1995) Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index: development, validation and application of a new instrument. Br J Surg 82:216–222

Ho KS, Eu KW, Heah SM et al (2000) Randomized clinical trial of hemorrhoidectomy under a mixture of local anaesthesia versus general anaesthesia. Br J Surg 87:410–413

Ooi BS, Ho Y-H, Tang CL et al (2002) Results of stapling and conventional hemorrhoidectomy. Tech Coloproctol 6:59–60

Filingeri V, Gravante G, Baldessari E et al (2004) Prospective randomized trial of submucosal hemorrhoidectomy with radiofrequency bistoury vs. conventional Parks’ operation. Tech Coloproctol 8:31–36

Ramadan E, Vishne T, Dreznik Z (2002) Harmonic scalpel hemorrhoidectomy: preliminary results of a new alternative method. Tech Coloproctol 6:89–92

You SY, Kim SH, Chung CS, Lee DK (2005) Open vs. closed hemorrhoidectomy. Dis Colon Rectum 48:108–113

Nisar PJ, Acheson AG, Neal KR, Scholefield JH (2004) Stapled hemorrhoidopexy compared with conventional hemorrhoidectomy: systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Dis Colon Rectum 47:1837–1845

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ho, K.S., Ho, Y.H. Prospective randomized trial comparing stapled hemorrhoidopexy versus closed Ferguson hemorrhoidectomy. Tech Coloproctol 10, 193–197 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-006-0279-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-006-0279-9