Abstract

Background

Cancer cachexia (CC) is a debilitating syndrome severely impacting patients’ quality of life and survivorship. We aimed to investigate the health care professionals’ (HCPs’) experiences of dealing with CC.

Methods

Survey questions entailed definitions and guidelines, importance of CC management, clinician confidence and involvement, screening and assessment, interventions, psychosocial and food aspects. The online survey was disseminated through Australian and New Zealand palliative care, oncology, allied health and nursing organisations. Frequencies were reported using descriptive statistics accounting for response rates. Associations were examined between variables using Fisher’s exact and Pearson’s chi-square tests.

Results

Over 90% of the respondents (n = 192) were medical doctors or nurses. Over 85% of the respondents were not aware of any guidelines, with 83% considering ≥ 10% weight loss from baseline indicative of CC. CC management was considered important by 77% of HCPs, and 55% indicated that it was part of their clinical role to assess and treat CC. In contrast, 56% of respondents were not confident about managing CC, and 93% believed formal training in CC would benefit their clinical practice. Although formal screening tools were generally not used (79%), 75% of respondents asked patients about specific symptoms. Antiemetics (80%) and nutritional counselling (86%) were most prescribed or recommended interventions, respectively.

Conclusion

This study underlines the deficiencies in knowledge and training of CC which has implications for patients’ function, well-being and survival. HCP training and a structured approach to CC management is advocated for optimal and continued patient care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cancer cachexia (CC) is a multifactorial metabolic syndrome encompassing appetite and weight loss and severe muscle wasting [1, 2]. Cachexia is estimated in 80% of people with advanced cancer [3,4,5], and is implicated in around 20% of cancer deaths [6]. CC is associated with the reduced tolerance of ongoing cancer treatments, increased toxicity and treatment delays and is an independent predictor of survival [7,8,9]. Reduced physical, social and psychological functioning [10] affects the quality of life of the patient and causes distress for carers who see this as a harbinger of death [11].

While it is a prevalent and devastating syndrome [12], cachexia assessment and management remains an unmet medical need for many people with cancer [2, 12,13,14]. Previously, three global surveys undertaken across 14 countries investigated goals of treatment practices and highlighted the need for the increased awareness and management of CC among health care professionals (HCPs) [13]. Semi-structured interviews undertaken in a dedicated cachexia clinic concurred that improved knowledge would increase staff confidence to broach CC with patients and their carers [15]. Another focus group/semi-structured study added that culture and available resources underpinned a holistic model of care approach [16]. Although this research has outlined the need for more attention in tackling CC, little is known about the current understanding and work practices of HCPs regarding CC management. Thus, this study investigated the HCPs’ experiences of dealing with CC. Furthermore, we examined whether previous survey findings extended to Australia and New Zealand.

Methods

Forty-six multi-choice and 18 other/open questions were formulated to reflect current CC knowledge [13, 15, 16] under the headings: definitions and guidelines; importance of CC management; HCP confidence and involvement; screening and assessment tools; pharmaceutical and nonpharmaceutical interventions; psychosocial and food aspects.

As the first local initiative, there was no external validation of the questions. The survey was constructed in REDCap (Vanderbilt University, U.S.A.) and tested prior to dissemination. The survey link was sent to oncology, palliative care and allied health organisations (n = 9) which was then distributed to their respective memberships. The survey was open between 29th September 2018 and 26th July 2019. This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was obtained from the Faculty of Health Low Risk Ethics Panel (Reference number ETH18-2870), University of Technology Sydney, Australia. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data were analysed using SPSS Statistics software (V19; Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Frequencies were described, and the results were reported using descriptive statistics accounting for response rates. Fisher’s exact and Pearson chi-square tests examined the association between two or more variables, respectively. P < 0.05 showed an association between the variables. Responses of other/open questions were tabulated and summarised (Supplementary 1).

Results

Survey participation and respondent’s demographics

A flow diagram for the data process is shown in Fig. 1. In this study, 192 respondents indicated that they were HCPs and were included in the analysis. Most respondents lived in Australia, worked in palliative care and were medical doctors or nurses (Table 1). The results were summarised into three main themes: knowledge, clinical practice and clinical management in CC.

Knowledge

Awareness of definitions and guidelines for cancer cachexia

Thirty-five percent of respondents reported awareness of the consensus definition of CC (n = 176) [2] however, 83% incorrectly reported that weight loss of ≥ 10% corresponded to CC (n = 174). HCPs were aware of the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) guidelines (n = 165) [17] (Table 2). Complementing this finding, 80% and 91% of respondents wanted a better understanding of the physiological processes and current CC guidelines, respectively.

Clinician confidence and training in cancer cachexia

Fifty-six percent of respondents were neutral or lacked confidence in managing people with CC (n = 135) (Table 2). Ninety-two percent (n = 131) indicated that a central place for CC information would aid clinicians’ confidence in managing and discussing CC. Over 70% of the HCPs were comfortable discussing the psychosocial impact of CC with patients and their carers (Table 2). Only 16% reported receiving any training in CC, and 93% indicated that formal training or education would benefit their clinical practice. Ninety-seven percent (n = 147) agreed that further clinical research in CC and its impact on patients was required.

Clinical practice

Clinician involvement: use of a multidisciplinary team

Eighty-eight percent (n = 135) of respondents reported that multidisciplinary team meetings were part of their current practice, with the following personnel involved (n = 119): medical doctors (92%), nursing (98%), dietitian (48%), physiotherapist (63%), occupational therapist (64%), psychologist/social worker (78%), counsellor (29%), speech pathologist (24%) and other (24%). Assessment (56%), treatment (59%) and monitoring (51%) were discussed (n = 192). Table 3 shows the frequency of these HCPs’ involvement with patients, with medical doctors and nurses involved in “regular review”, whilst other personnel were involved “as needed”.

Forty-two percent (n = 119) reported that specific personnel were missing from the multidisciplinary team (n = 49): medical doctors (10%), nursing (4%), dietitian (57%), physiotherapist (41%), occupational therapist (29%), psychologist/social worker (16%), counsellor (37%), speech pathologist (61%) and other (16%).

Screening for cancer cachexia

Fifty-five percent of respondents assessed and treated CC in their practice (n = 143), with only 17 (22%, n = 79) using formal nutrition screening tools (Table 3). The Malnutrition Screening Tool (MST) was used by 77% (of n = 17). Seventy-five percent (n = 79) screened for specific symptoms related to CC, with 75% reassessing the symptoms at each review (n = 59). All respondents screened for poor appetite.

Pathology tests for CC screening (n = 79) was used by 43% of respondents. Most frequently prescribed tests were albumin/pre-albumin, haemoglobin, calcium, C-reactive protein/erythrocyte sedimentation rate (CRP/ESR) and blood sugar level. Thirty-three percent reported using biometric tests (n = 79), with weight (100%) and body mass index (BMI) (73.1%) most measured.

Assessment tools used in cancer cachexia

Forty-five percent of respondents monitored CC beyond initial screening (n = 139). Many of these assessment tools (Table 3) were rated as “not applicable” (> 70%). Standard practice assessments such symptom monitoring was “ongoing” (65%), whilst pathology (44%) and biometric assessments were “as needed” (24%).

Clinical management

Importance of cancer cachexia management

Seventy-seven percent of respondents indicated that CC management was an important part of their practice (n = 149), with two thirds of this sub-group noting that it was important when compared to other symptoms (Table 4). Carers (40%) were more likely to initiate discussions regarding CC management.

Pharmaceutical and nonpharmaceutical interventions

Antiemetics, prokinetic agents and steroids were the most prescribed medications, with megestrol acetate less popular (Table 4). Agents such as androgens, anamorelin, cannabinoids and thalidomide were less frequently prescribed. Over 80% of respondents recommended the nonpharmaceutical management of CC including nutritional counselling, psychological support and mouth care.

Food aspects

Restrictive eating practices (e.g. eliminating refined sugar/gluten free diet/vegan diet/alkaline diet etc.) and cultural attitudes towards food were likely to be asked by 54% and 59% of the respondents, respectively (n = 133).

Statistical analysis

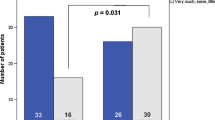

Fisher’s exact test results (Table 5) showed an association with the 2011 definition and pathology tests (p = 0.01); ESPEN Guidelines with formal nutritional tool (p = 0.04); current practice to assess and treat CC and awareness of the ESPEN Guidelines or other/local guidelines (both p = 0.00).

Pearson chi-square test (Table 5) showed an association between occupation (medical doctors, nursing, dietitian/physiotherapist/occupational therapist/psychologist/social work/others) and ESPEN guidelines [Χ2 (2, N = 165) = 24.184, p = 0.00]; occupation and other/local guidelines [Χ2 (2, N = 166) = 9.514, p = 0.01] and borderline association with occupation and 2011 consensus definition [Χ2 (2, N = 176) = 5.967, p = 0.05].

Discussion

This study demonstrates that the multifactorial nature of CC extends to the experiences of HCPs involved in its assessment and management. The survey revealed that HCPs assess their management of CC as poor. These issues were explored within three domains: knowledge, clinical practice and clinical management.

Knowledge

Few HCPs were aware of key definitions or current guidelines. Consistent with previous studies, most respondents did not diagnose CC until weight loss ≥ 10% [18, 19], suggesting that early cachexia will be undiagnosed and untreated.

The lack of awareness of guidelines perhaps also reflects a recent review highlighting the heterogeneity within and between guidelines, illustrating the difficulty of advocating for particular guidelines [20]. Despite this, there was an association between assessing and treating CC and awareness of ESPEN/other guidelines and clinician occupation with 2011 consensus definition/ESPEN/other guidelines suggesting that HCPs are likely consulting guidelines for CC management, and thus the need for guidelines to be kept current. However, it should be noted that the awareness of guidelines is futile if clinicians are not reading, understanding or using the guidelines, and this needs to be advocated for at the workplace and/or in any training of CC.

In this study, nearly all respondents identified that formal training/education in CC would benefit their clinical practice to improve their confidence. These responses reflect previous studies which demonstrated that knowledge and understanding of CC and its effects on patients are essential for managing it [13, 15, 16, 21]. Nearly all respondents also agreed that further CC research and its impact on patients is required, reflecting the complexity of the syndrome. Most respondents were comfortable discussing the psychosocial impact of CC with their patients and carers, potentially reflecting the preponderance of respondents who worked in palliative care with its emphasis on the relief of physical and psychosocial suffering.

Clinical practice

Recent studies have highlighted the significance of recognising cachexia as a debilitating syndrome [22] and the importance of specialised care for patients and their carers [15]. The multidisciplinary approach to CC is advocated to support the patient and carer, and can only work if each clinical discipline contributes [23]. With weight loss and anorexia being hallmarks of CC, it is concerning that only one fifth of respondents reported “regular review” by a dietitian despite current clinical guidelines [17, 24]. Most allied health involvement was ad hoc rather than a structured multidisciplinary approach to CC management contrasting with evidence that, for example, physiotherapists have a role to maintain and potentially rebuild muscle stores [25, 26]. Psychologists, social workers and counsellors were involved “as needed” which may suggest that they are not considered as core personnel in CC management and may be an area of under servicing in CC management [11, 27]. These results need to be considered in the light of a recent study demonstrating the positive effects of the multidisciplinary team in CC management [28]. It is noteworthy that the current American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guideline does not recommend any specific clinical disciplines [24].

Although there was a statistically significant association with formal nutritional screening tools and the ESPEN guidelines, very few respondents used them. The MST is mandatory within public hospitals in one state of Australia (NSW) and its use is supported by a study which showed that the tool had the greatest ability to detect cachexia among patients with gastric cancer when compared to other tools [29]. Around three-quarters of respondents screened for specific symptoms and reassessed these at each review, emphasising the importance of co-screening and symptom control [30, 31].

Biometric testing such as mid arm strength etc. was rarely used in clinical practice most likely indicating minimal understanding of its application. Weight or BMI is a simple diagnostic tool to indicate potential CC [32], but this was rarely recorded by clinicians. One study showed that 56% of hospice staff considered weighing would cause patient distress, while 96% of patients did not find weighing to be upsetting [33]. Missing this early prognostic sign could impact quality of life and the potential to address the syndrome [18, 34].

Diagnosing CC is complicated by poor agreement on biomarker criteria [35]. Pathology tests were rarely used by respondents. Interestingly, our results showed a statistically significant association between pathology screening for CC and awareness of the 2011 consensus definition which may indicate that these HCPs have knowledge of the diagnosis of CC.

The low use of assessment tools, such as quality of life, mirrored the low use of other screening tools which could reflect the lack of training in their application. Most respondents used “regular” symptom and “as needed” pathology assessments most likely reflecting standard practice of generic symptom and blood monitoring. A structured approach to assessment (e.g. combining PG-SGA and a symptoms and concerns checklist) and simple advice have been shown to reduce symptom burden, especially in people with advanced cancer [36]. Respondents were keen on a central repository for CC-related tools and information which may increase their uptake.

Clinical management

Although over three-quarter of respondents indicated that CC management was an important part of their clinical practice, it was the carers who were more likely to initiate the discussion/management of CC, consistent with one previous study [37]. This may reflect HCPs’ reluctance to discuss cachexia with their patients because of the link to a poor prognosis [38].

Clinical management is made more difficult because there is no registered medication to manage CC (except in Japan), with most treatments geared toward appetite improvement [39]. Anorexia has a profound impact on a person’s oral intake, often worsening weight loss [40]. Responses reflected locally available therapies used for anorexia: antiemetics and prokinetics [17, 24].

There was an emphasis on nonpharmaceutical interventions—psychological support, nutrition counselling, exercise and mouth care which may reflect the lack of any definitive treatment. Nutritional intake may be significantly influenced by comorbidities and/or personal and cultural preferences, which adds additional complexity to advice, and further supports the inclusion of dietitians in managing CC. Notably, the ASCO guidelines do not recommend any interventions for managing CC [24].

The study’s strength is the inclusion of a range of health care disciplines and the holistic view of HCP’s management of CC, with domains and results comparable to studies undertaken in other countries. A limitation of this survey is the low response rate. This could indicate the HCPs’ current workload, unwillingness to complete a relatively long survey, or CC being a low priority in their practice.

Conclusion

This study underlines the need for HCP training and national support for the systematic assessment and management of CC. Although access to a multidisciplinary team is ideal, a simplified, systematic approach incorporating screening, assessment and evidence-based interventions is recommended for ongoing patient care. Future research needs to examine whether earlier diagnosis of, and intervention(s) for, CC have positive impacts during cancer treatment and survival. It is recommended that the patient and carer experience of CC management be investigated to understand their perceptions and focus future research.

Availability of data and materials (data transparency)

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Dhanapal R, Saraswathi TR, Govind RN (2011) Cancer cachexia. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 15(3):257–260. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-029X.86670

Fearon K, Strasser F, Anker SD et al (2011) Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol 12(5):489–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70218-7

Poole K, Froggatt K (2002) Loss of weight and loss of appetite in advanced cancer: a problem for the patient, the carer, or the health professional? Palliat Med 16:499–506. https://doi.org/10.1191/0269216302pm593oa

Anker MS, Holcomb R, Muscaritoli M et al (2019) Orphan disease status of cancer cachexia in the USA and in the European Union: a systematic review. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 10(1):22–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12402

Sun L, Quan X-Q, Yu S (2015) An epidemiological survey of cachexia in advanced cancer patients and analysis on its diagnostic and treatment status. Nutr Cancer 67(7):1056–1062. https://doi.org/10.1080/01635581.2015.1073753

Bachmann P, Marti-Massoud C, Blanc-Vincent MP et al (2003) Summary version of the standards, options and recommendations for palliative or terminal nutrition in adults with progressive cancer (2001). Br J Cancer 89(Suppl 1):S107–S110. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6601092

Aapro M, Arends J, Bozzetti F et al (2014) Early recognition of malnutrition and cachexia in the cancer patient: a position paper of a European School of Oncology Task Force. Ann Oncol 25:1492–1499. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdu085

Daly LE, Ni Bhuachalla EB, Power DG et al (2018) Loss of skeletal muscle during systemic chemotherapy is prognostic of poor survival in patients with foregut cancer. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 9(2):315–325. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12267

da Rocha IMG, Marcadenti A, Medeiros GOC et al (2019) Is cachexia associated with chemotherapy toxicities in gastrointestinal cancer patients? A prospective study. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 10(2):445–454. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12391

Gelhorn HL, Gries KS, Speck RM et al (2019) Comprehensive validation of the functional assessment of anorexia/cachexia therapy (FAACT) anorexia/cachexia subscale (A/CS) in lung cancer patients with involuntary weight loss. Qual Life Res 28:1641–1653. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02135-7

Oberholzer R, Hopkinson J, Baumann K et al (2013) Psychosocial effects of cancer cachexia: a systematic literature search and qualitative analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage 46(1):77–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.06.020

Vagnildhaug OM, Balstad TR, Almberg SS et al (2018) A cross-sectional study examining the prevalence of cachexia and areas of unmet need in patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer 26(6):1871–1880. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-4022-z

Muscaritoli M, Rossi Fanelli F, Molfino A (2016) Perspectives of health care professionals on cancer cachexia: results from three global surveys. Ann Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdw420

Mueller TC, Burmeister MC, Bachmann J et al (2014) Cachexia and pancreatic cancer: are there treatment options? World J Gastroenterol 20(28):9361–9373. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i28.9361

Scott D, Reid J, Hudson P et al (2016) Health care professionals’ experience, understanding and perception of need of advanced cancer patients with cachexia and their families: the benefits of a dedicated clinic. BMC Palliat Care 15(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-016-0171-y

Millar C, Reid J, Porter S (2013) Healthcare professionals’ response to cachexia in advanced cancer: a qualitative study. Oncol Nurs Forum 40(6):E393–E402

Arends J, Bachmann P, Baracos V et al (2017) ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. Clin Nutr 36(1):11–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2016.07.015

Muscaritoli M, Molfino A, Lucia S et al (2015) Cachexia: a preventable comorbidity of cancer. a T.A.R.G.E.T approach. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 94:251–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2014.10.014

Ni J, Zhang L (2020) Cancer cachexia: definition, staging, and emerging treatments. Cancer Manag Res 12:5597. https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S261585

Shen W-Q, Yao L, Wang X-q et al (2018) Quality assessment of cancer cachexia clinical practice guidelines. Cancer Treat Rev 70:9–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.07.008

Churm D, Andrew IM, Holden K et al (2009) A questionnaire study of the approach to the anorexia–cachexia syndrome in patients with cancer by staff in a district general hospital. Support Care Cancer 17(5):503–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-008-0486-1

Porporato P (2016) Understanding cachexia as a cancer metabolism syndrome. Oncogenesis 5(2):e200–e200. https://doi.org/10.1038/oncsis.2016.3

Cooper C, Burden ST, Cheng H et al (2015) Understanding and managing cancer-related weight loss and anorexia: insights from a systematic review of qualitative research. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 6(1):99–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12010

Roeland EJ, Bohlke K, Baracos VE et al (2020) Management of cancer cachexia: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol 38(21):2438–2453. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.20.00611

Solheim TS, Laird BJ, Balstad TR et al (2018) Cancer cachexia: rationale for the MENAC (Multimodal—Exercise, Nutrition and Anti-inflammatory medication for Cachexia) trial. BMJ Support Palliat Care 8(3):258–265. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2017-001440

Granger CL, Parry SM, Edbrooke L et al (2016) Deterioration in physical activity and function differs according to treatment type in non-small cell lung cancer–future directions for physiotherapy management. Physiotherapy 102(3):256–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2015.10.007

Reid J (2014) Psychosocial, educational and communicative interventions for patients with cachexia and their family carers. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 8(4):334–338. https://doi.org/10.1097/spc.0000000000000087

Bland KA, Harrison M, Zopf EM et al (2021) Quality of life and symptom burden improve in patients attending a multidisciplinary clinical service for cancer cachexia: a retrospective observational review. J Pain Symptom Manage. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.02.034

Chen X-Y, Zhang X-Z, Ma B-W et al (2020) A comparison of four common malnutrition risk screening tools for detecting cachexia in patients with curable gastric cancer. Nutrition 70:110498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2019.04.009

Zhou T, Yang K, Thapa S et al (2017) Differences in symptom burden among cancer patients with different stages of cachexia. J Pain Symptom Manage 53(5):919–926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.325

Maddocks M, Hopkinson J, Conibear J et al (2016) Practical multimodal care for cancer cachexia. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 10(4):298. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPC.0000000000000241

Martin L, Senesse P, Gioulbasanis I et al (2015) Diagnostic criteria for the classification of cancer-associated weight loss. J Clin Oncol 33(1):90–99. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.56.1894

Watson M, Coulter S, McLoughlin C et al (2010) Attitudes towards weight and weight assessment in oncology patients: survey of hospice staff and patients with advanced cancer. Palliat Med 24(6):623–629. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216310373163

Tarricone R, Ricca G, Nyanzi-Wakholi B et al (2016) Impact of cancer anorexia-cachexia syndrome on health-related quality of life and resource utilisation: a systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 99:49–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.12.008

Orell-Kotikangas H, Österlund P, Mäkitie O et al (2017) Cachexia at diagnosis is associated with poor survival in head and neck cancer patients. Acta Otolaryngol 137(7):778–785. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016489.2016.1277263

Andrew IM, Waterfield K, Hildreth AJ et al (2009) Quantifying the impact of standardized assessment and symptom management tools on symptoms associated with cancer-induced anorexia cachexia syndrome. Palliat Med 23(8):680–688. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216309106980

Rhondali W, Chisholm GB, Daneshmand M et al (2013) Association between body image dissatisfaction and weight loss among patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers: a preliminary report. J Pain Symptom Manage 45(6):1039–1049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.06.013

Millar C, Reid J, Porter S (2013) Refractory cachexia and truth-telling about terminal prognosis: a qualitative study. Eur J Cancer Care 22:326–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12032

Aoyagi T, Terracina KP, Raza A et al (2015) Cancer cachexia, mechanism and treatment. World J Gastrointest Oncol 7(4):17. https://doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v7.i4.17

Siddiqui JA, Pothuraju R, Jain M et al (2020) Advances in cancer cachexia: intersection between affected organs, mediators, and pharmacological interventions. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) Rev Cancer 1873(2):188359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2020.188359

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank: Mr Aaron Shannon-Hobson and Mr Manraaj Singh (University of Technology Sydney Australia) for their help with the construction of the survey within REDCap; Dr Mathew Grant for providing feedback on the survey; the following organisations for disseminating the survey: Allied Health in Palliative Care, Cancer Nurses Society Australia, Clinical Oncology Society of Australia (COSA), New Zealand Society for Oncology, Palliative Care Clinical Studies Collaborative (PaCCSC), Palliative Care Nurses Australia, Palliative Care Nurses New Zealand, Palliverse, The Australian & New Zealand Society of Palliative Medicine Inc. (ANZSPM) and the HCPs for their participation in the survey.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. This study was supported by the Palliative Care Clinical Studies Collaborative (PaCCSC), University of Technology Sydney, Australia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LB: Conceptualization and Resources; MP: Investigation; SC: Data curation and Formal analysis; DC: Visualisation; JEs: Writing—original draft; VRN: Methodology, Project administration and Supervision, Writing—original draft, Formal analysis; All authors: Methodology, Writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

DCC is an unpaid member of an advisory board for Helsinn Pharmaceuticals and has consulted to Mayne Pharma and received intellectual property payments from them. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Ellis, J., Petersen, M., Chang, S. et al. Health care professionals’ experiences of dealing with cancer cachexia. Int J Clin Oncol 28, 592–602 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-023-02300-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-023-02300-6