Abstract

Background

Individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis is considered to be a gold standard when the results of several randomized trials are combined. Recent initiatives on sharing IPD from clinical trials offer unprecedented opportunities for using such data in IPD meta-analyses.

Methods

First, we discuss the evidence generated and the benefits obtained by a long-established prospective IPD meta-analysis in early breast cancer. Next, we discuss a data-sharing system that has been adopted by several pharmaceutical sponsors. We review a number of retrospective IPD meta-analyses that have already been proposed using this data-sharing system. Finally, we discuss the role of data sharing in IPD meta-analysis in the future.

Results

Treatment effects can be more reliably estimated in both types of IPD meta-analyses than with summary statistics extracted from published papers. Specifically, with rich covariate information available on each patient, prognostic and predictive factors can be identified or confirmed. Also, when several endpoints are available, surrogate endpoints can be assessed statistically.

Conclusions

Although there are difficulties in conducting, analyzing, and interpreting retrospective IPD meta-analysis utilizing the currently available data-sharing systems, data sharing will play an important role in IPD meta-analysis in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 2009, a special issue of the International Journal of Clinical Oncology reviewed the implementation and limitations of the meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs). This special issue included a general discussion of the role of meta-analysis [1], implementation of the tabulated-data meta-analysis [2], additional contributions of individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis [3], and the development of the statistical methods for performing IPD meta-analysis [4]. In these articles the benefits of IPD meta-analysis were discussed, and IPD meta-analysis was presented as a gold standard for conducting a quantitative review of evidence arising from randomized clinical trials.

Historically, meta-analysis started in the early 1980s when it became apparent that many randomized trials were too small to reliably establish the effects, or lack thereof, of most treatments of patients with cancer and cardiovascular diseases [5, 6]. The need to combine data from several trials led to early meta-analyses based on summary statistics extracted from the published results of randomized trials. Such meta-analyses suffered from poorly standardized data, publication bias, selective reporting, and other sources of bias, such as post hoc choices of the hypotheses tested. The pioneering work of the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) led to the creation of several research groups with the aim to conduct IPD meta-analyses. These groups started with retrospective meta-analyses and then continued with prospective meta-analyses of trials conducted by the same investigators or research groups. A prospective meta-analysis is a meta-analysis in which eligible randomized trials are identified before their results are known. In comparison, in a retrospective meta-analysis efforts are made to identify all ongoing trials, both to maximize precision and to avoid publication bias [7]. A prospective meta-analysis may be limited to a small number of investigators or research groups who standardize outcomes and case report forms used to collect the data.

More recently, the concept of sharing IPD from clinical trials has attracted much attention in major journals as well as in some regulatory agencies [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. The current trend toward sharing data has the potential to revolutionize IPD meta-analysis if the data-sharing policy is successfully implemented in the years to come. Our purpose in this paper is to discuss the respective advantages and limitations of retrospective IPD meta-analyses utilizing data-sharing systems as compared with those of prospective meta-analyses conducted by large collaborative groups. We first introduce the EBCTCG as an example of prospective IPD meta-analysis to focus on the evidence this group has generated over the last three decades. Next, we review the data-sharing system and discuss examples of a retrospective IPD meta-analysis that uses this data-sharing system. Finally, we discuss the role of data sharing for IPD meta-analysis in the future.

Example of prospective IPD meta-analysis: EBCTCG

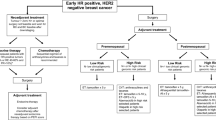

The EBCTCG is one of the world’s largest meta-analysis groups (Table 1). It was initiated in 1985 with the aim of collaborating the work of various research groups studying the treatment of early breast cancer and currently involves the collaboration of hundreds of such research groups from around the world [20]. Over the last 30+ years, the EBCTCG has identified more than 600 randomized trials of treatments for women with operable breast cancer and collected IPD from more than 400 of these, involving a total of 460,000 women. In the early 1990s, the EBCTCG routinely sought IPD from every randomized trial that had compared treatments for women with operable breast cancer in which recurrence or mortality was a principal outcome. The comparisons being tackled in the present decade relate to hormonal therapy, chemotherapy, other systemic therapies, and local therapy, in which death from secondary cancers, non-breast-cancers, and/or cardiovascular diseases are principal outcomes in addition to recurrence or mortality. The study results of the EBCTCG can be obtained at the webpage of the Clinical Trial Service Unit and Epidemiological Studies Unit [21].

The variables that are to be provided by the collaborators are specified on this webpage, namely, patient characteristics, surgical details, nodal status, tumor characteristics, receptor status, non-compliance before any recurrence, cancer recurrence and second cancers, survival, additional tumor marker data, bone fractures and cardiovascular events, and trials with neo-adjuvant systemic therapy. Each collaborator prepares the data formatted as “one record for each woman,” and the statistical group in Oxford conducts the meta-analysis in cooperation with the steering committee of EBCTCG. What kind of evidence can be obtained through the above prospective collaboration and preparation of the standardized data as indicated? As an example of prospective IPD meta-analysis, we introduce one of the results of the EBCTCG [22], which highlights a number of important components of prospective IPD meta-analysis.

The study was a meta-analysis of all RCTs which targeted effective adjuvant therapy for early breast cancers and had been initiated from 1973 to 2003. Two primary endpoints were death from breast cancer and death from any cause. The meta-analysis included data from as many as 100,000 patients collected between 2005 and 2010 and could not have been done without an IPD meta-analysis; in other words, such an analysis based on latest data cannot be done with a tabulated-data meta-analysis. Moreover, the study collaborators were requested to send the IPDs of “ever randomized patients,” which included any woman who was randomized and then was later categorized as ineligible, withdrawn, unevaluable, lost to follow-up, or protocol deviant. Having data on all “ever randomized patients,” investigators can assess the impact of excluding some patients from the meta-analysis (selection bias), which is only possible when IPD are available.

While the main object of the IPD meta-analysis was to compare the treatment regimens for all early breast cancer patients included in the individual studies, the IPD also included covariates which affect survival; hence, the meta-analysis could also assess treatment effects in various patient subgroups. The study reported that the treatment regimens scarcely affected the overall survival between the subgroups of age, status of lymph nodes, tumor size, differentiation, estrogen receptor, or tamoxifen history, based on the Chi-squared statistic of heterogeneity (Fig. 6 of [22]).

Anthracycline-based regimens are known to have adverse cardiac effects, but the incidence was too small to be estimated reliably in individual trials. In the IPD meta-analysis, untoward effects of anthracycline-based regimens could be estimated accurately ([22], pp. 441–442).

This example of a prospective IPD meta-analysis performed by the EBCTCG illustrates many important advantages of IPD meta-analysis, in particular the absence of publication bias because of the prospective nature of the meta-analysis. However, a long and difficult process that can take several years and require a sophisticated organization is one of the limitations of prospectively obtaining IPD. Authors have been conducting retrospective IPD meta-analysis for over 15 years but it is also difficult and time-consuming to obtain IPD for a retrospective IPD meta-analysis [23,24,25,26,27]. Recently, however, data-sharing initiatives have been discussed in the medical literature [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. If data sharing can be put into practice, retrospective IPD meta-analysis may be the more efficient option compared to (or sometimes in addition to) prospective ones in terms of conducting an IPD meta-analysis.

Data sharing and retrospective IPD meta-analysis

Sharing IPD from clinical trials is an increasing trend among stakeholders involved in medical research [28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) published a draft “Policy on publication and access to clinical-trial data: Policy 0070” in June 2013, with finalization of the policy in October 2014 [35]. In January 2014, the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Association (EFPIA) and the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) jointly implemented “Principles for Responsible Clinical Trial Data Sharing” [36]. In these Principles, enhancing the sharing of anonymized patient-level and study-level data with qualified researchers is described as one of the commitment of biopharmaceutical companies. In January 2016, the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) proposed that sharing of the de-identified IPD of any clinical trial submitted for publication to an ICMJE journal no later than 6 months after publication should be a prerequisite for publication [14]. More recently, the ICMJE decided that after 1 July 2018 all authors submitting a clinical trial study for publication have to agree to these data-sharing statements at the time of manuscript submission [15]. In line with these policies, most pharmaceutical companies have launched data-sharing initiatives. Some companies share the data on their own webpages, while others utilize a common system for data sharing, such as Clinical Study Data Request (CSDR) [37], Yale University Open Data Access (YODA) [38] and Project Data Sphere [39].

CSDR is one of the largest common multi-sponsor systems for data sharing, being initiated by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) [40]. Thirteen pharmaceutical companies have participated in this system up to August 2017, and overviews of their activity during the first 2 years have been published [41, 42]. Researchers can use the CSDR webpage to request access to anonymized IPD and supporting documents from clinical studies conducted by study sponsors that are committed to participate in CSDR. In order to request IPD from the studies listed on the website, researchers have to submit their research proposals, including a statistical analysis plan. The request for IPD after submission of research proposals is assessed as follows: (1) requirement checks; (2) review by independent review panel; (3) data sharing agreement; (4) de-identified data preparation by the sponsor; and (5) data analysis. The details of a research proposal which has been approved for data sharing can be followed on the webpage (see Metrics in [37]). The types of research projects are very diverse, including re-analysis of the data of the published study and meta-analysis based on either tabulated data or IPD. Of the 174 research proposals approved of up to 31 August 2017, 12 proposals were IPD meta-analysis, including network meta-analysis (Table 2).

Using the IPD of previous studies through a system of data sharing, such as CSDR, researchers can conduct retrospective IPD meta-analyses. In contrast to a prospective IPD meta-analysis, such as that conducted by EBCTCG, each study shared in the system is not intended to be used in the meta-analysis and, therefore, variables included in each study are not necessarily consistent across different studies.

An example of a retrospective IPD meta-analysis currently in progress is that of Schünemann et al. who initially published the design of their research project using data obtained through CSDR [43]. Subsequent to their previous study-level systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the role of parenteral anticoagulants in patients with cancer, the results of which suggest a survival benefit and a reduction in venous thromboembolism, these researchers are conducting an IPD meta-analysis to further investigate the questions that remain unanswered. Specifically, their primary objective is to explore the magnitude of the survival benefit of parenteral anticoagulants and to address which subgroups of patients with cancer are more likely to benefit from parenteral anticoagulants. To this end, they identified 15 randomized trials that fulfill their eligibility criteria. Two of these are among the studies available on CSDR. Consequently, these investigators submitted research proposals and requested anonymized data from the studies. Their requests were agreed to in July 2014 for the INPACT Study [44] (sponsored by GSK) and in March 2016 for the SAVE-ONCO Study [45] (sponsored by Sanofi). For the other studies deemed eligible for inclusion in their meta-analysis (13 of 15 trials), Schünemann and colleagues contacted the authors of each study directly and requested them to share their data. Using the shared IPD, their research project is currently in progress. For the analysis of mortality, the primary outcome, multilevel models will be used that include patient-level variables, such as comorbidities and age, as fixed effects and trial as a random effect. In order to test for a differential treatment effect among the various pre-specified subgroups defined by type and stage of cancer or concomitant treatment, tests of interaction will be conducted. In addition, a risk-prediction model for venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer will be developed using logistic regression or Cox proportional hazards regression. With data from a total of more than 9000 participants, the strength of their IPD meta-analysis is the possibility of identifying patient-level effect modifiers and exploring more precisely the survival benefit suggested by their previously published tabulated-data meta-analysis.

Discussion

We have reviewed IPD meta-analyses conducted prospectively and retrospectively. The characteristics of prospective and retrospective IPD meta-analysis compared to tabulated-data meta-analysis are summarized in Table 3. In both types of IPD meta-analyses, the availability of detailed covariate information for each patient allows investigators to examine the effect of risk factors and treatment effect modifiers.

In order to conduct IPD meta-analysis, it is often necessary to put in place a large collaborative group. Large and long-lasting collaborative groups such as the EBCTCG have enabled investigators to examine important research questions that could not be answered in individual studies. However, such a prospective IPD meta-analysis also takes much time and adequate financial resources, not only to fund the central office of the IPD meta-analysis, but also to fund all the groups who share their data.

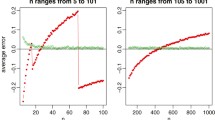

To the contrary, it is reasonable to expect that a retrospective IPD meta-analysis will be easy to conduct in the era of data sharing. Nevitt et al. recently conducted a systematic review of 760 IPD meta-analyses and only 25% of these retrieved 100% of eligible IPD for the respective analysis [46]. With a system of data sharing such as CSDR, it may be possible for researchers to use IPD of previous studies without the overhead of a large collaborative group. Very few studies of IPD meta-analysis using CSDR have been reported to date [47,48,49]. In the case of CSDR, researchers can submit requests to sponsors to inquiry about the availability of data from studies that are not listed on the website; however, the number of such inquiries has thus far been surprisingly small (See Metrics on CSDR webpage). It is likely that a retrospective IPD meta-analysis using a data sharing system is more vulnerable to publication bias, if investigators use a sample of convenience (studies available on a data sharing system) rather than the totality of all trials ever conducted on the question of interest.

Despite its scientific merits of data sharing, it is always associated with the protection of sensitive personal information. The draft policy of the EMA acknowledges the importance of personal data protection when sharing IPD [35], but the procedures by which an acceptable level of protection can be achieved are as yet unclear. In Japan, the ethical guidelines for medical and health research involving human subjects issued by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology/Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in 2015 contained no official statement of data sharing [50]; however, amendments in 2017 included the amendment of the act on the Protection of Personal Information. A well-balanced discussion is expected, and such a discussion may be imperative for encouraging data sharing and reaching a balance between the protection of personal data and scientific research value.

Data sharing has just started, and very few IPD meta-analyses using shared data have been conducted. Data sharing will accelerate access to the IPD of clinical trials, and a corresponding increase in the number of IPD meta-analyses conducted in the future can be expected. In conclusion, although there are some difficulties in conducting, analyzing, and interpreting retrospective IPD meta-analysis utilizing data sharing systems, data sharing most certainly will play an important role in IPD meta-analysis.

References

Hamada C (2009) The role of meta-analysis in cancer clinical trials. Int J Clin Oncol 14:90–94

Oba K (2009) Efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy using tegafur-based regimen for curatively resected gastric cancer: update of a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Oncol 14:85–89

Buyse M (2009) Contributions of meta-analyses based on individual patient data to therapeutic progress in colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol 14:95–101

Shi Q, Sargent DJ (2009) Meta-analysis for the evaluation of surrogate endpoints in cancer clinical trials. Int J Clin Oncol 14:102–111

Peto R, Collins R, Gray R (1995) Large-scale randomized evidence: large, simple trials and overviews of trials. J Clin Epidemiol 48:23–40

Buyse M, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Chalmers T (1988) Adjuvant therapy of colorectal cancer: why we still don’t know. JAMA 259:3571–3578

Higgins JPT, Green S (eds) (updated 2011) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration. http://handbook.cochrane.org. Accessed October 2017

Drazen JM (2015) Sharing individual patient data from clinical trials. N Engl J Med 372:201–202

Longo DL, Drazen JM (2016) Data sharing. N Engl J Med 374:276–277

Zarin DA (2013) Participant-level data and the new frontier in trial transparency. N Engl J Med 369:468–469

Tucker ME (2013) How should clinical trial data be shared? BMJ 347:f4465

Krumholz HM, Peterson ED (2014) Open access to clinical trials data. JAMA 312:1002–1003

Stewart LA, Clarke M, Rovers M et al (2015) Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analyses of individual participant data: the PRISMA-IPD statement. JAMA 313:1657–1665

Taichman DB, Backus J, Baethge C et al (2016) Sharing clinical trial data—a proposal from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. N Engl J Med 374:384–386

Taichman DB, Sahni P, Pinborg A et al (2017) Data sharing statements for clinical trials a requirement of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. JAMA 317:2491–2492

Bonini S, Eichler HG, Wathion N et al (2014) Transparency and the European Medicines Agency—sharing of clinical trial data. N Engl J Med 371:2452–2455

Committee on Strategies for Responsible Sharing of Clinical Trial Data, Board on Health Sciences Policy, Institute of Medicine (2015) Sharing clinical trial data: maximizing benefits, minimizing risk. National Academies Press, Washington, DC

[No authors listed] (1998) Protocol for prospective collaborative overviews of major randomized trials of blood-pressure lowering treatments. World Health Organization–International Society of Hypertension Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. J Hypertens 16:127–137

Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration (1995) Protocol for a prospective collaborative overview of all current and planned randomized trials of cholesterol treatment regimens. Am J Cardiol 75:1130–1134

Darby S, Davies C, McGale P (2005) The Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group: a brief history of results to date. In: Davison AC, Dodge Y, Wermuth N (eds) Celebrating statistics. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Oxford Clinical Trial Service Unit and Epidemiological Studies Unit. EBCTCG: Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. https://www.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/research/ebctcg. Accessed October 2017

Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) (2012) Comparisons between different polychemotherapy regimens for early breast cancer: meta-analyses of long-term outcome among 100,000 women in 123 randomised trials. Lancet 379:432–444

Meta-Analysis Group of the Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum and the Meta-Analysis Group in Cancer (2004) Efficacy of oral adjuvant therapy after resection of colorectal cancer: 5-year results from three randomized trials. J Clin Oncol 22:484–492

Sakamoto J, Hamada C, Rahman M et al (2005) An individual patient data meta-analysis of adjuvant therapy with carmofur in patients with curatively resected colon cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 35:536–544

The GASTRIC (Global Advanced/Adjuvant Stomach Tumor Research International Collaboration) Group (2010) Benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy for resectable gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA 303:1729–1737

The GASTRIC (Global Advanced/Adjuvant Stomach Tumor Research International Collaboration) Group (2013) Role of chemotherapy for advanced/recurrent gastric cancer: an individual-patient-data meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer 49:1565–1577

Oba MS, Teramukai S, Ohashi Y et al (2016) The efficacy of adjuvant immunochemotherapy with OK-432 after curative resection of gastric cancer: an individual patient data meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastric Cancer 19:616–624

Bauchner H, Golub RM, Fontanarosa PB (2016) Data sharing. An ethical and scientific imperative. JAMA 315:1237–1239

Bierer BE, Li R, Barnes M et al (2016) A global, neutral platform for sharing trial data. N Engl J Med 374:2411–2413

Geifman N, Bollyky J, Bhattacharya S et al (2015) Opening clinical trial data: are the voluntary data-sharing portals enough? BMC Med 13:280

Koenig F, Salttery J, Groves T et al (2015) Sharing clinical trial data on patient level: opportunities and challenges. Biom J 57:8–26

Lo B, DeMets DL (2016) Incentives for clinical trialists to share data. N Engl J Med 375:1112–1115

Navar AM, Pencina MJ, Rymer JA et al (2016) Use of open access platforms for clinical trial data. JAMA 315:1283–1284

Rockhold F, Nisen P, Freeman A (2016) Data sharing at a crossroads. N Engl J Med 375:1115–1117

European Medicines Agency (2014) European Medicines Agency policy on publication of clinical data for medicinal products for human use: policy/0070. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Other/2014/10/WC500174796.pdf. Accessed October 2017

European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations and Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (2013) Principles for responsible clinical trial data sharing. http://phrma-docs.phrma.org/sites/default/files/pdf/PhRMAPrinciplesForResponsibleClinicalTrialDataSharing.pdf. Accessed October 2017

ClinicalStudyDataRequest.com. ClinicalStudyDataRequest.com website. https://www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com/Default.aspx. Accessed October 2017

The YODA Project. The YODA project website. http://yoda.yale.edu/. Accessed October 2017

Project Data Sphere. Project data sphere website. https://www.projectdatasphere.org/projectdatasphere/html/home. Accessed October 2017

Nisen P, Rockhold F (2013) Access to patient-level data from GlaxoSmithKline clinical trials. N Engl J Med 369:475–478

Strom BL, Buyse M, Hughes J et al (2014) Data sharing, year 1—access to data from industry-sponsored clinical trials. N Engl J Med 371:2052–2054

Strom BL, Buyse M, Hughes J et al (2016) Data sharing—is the juice worth the squeeze? N Engl J Med 375:1608–1609

Schünemann HJ, Ventresca M, Crowther M et al (2016) Use of heparins in patients with cancer: individual participant data meta-analysis of randomised trials study protocol. BMJ Open 6:e010569

van Doormaal FF, Di Nisio M, Otten HM et al (2011) Randomized trial of the effect of the low molecular weight heparin nadroparin on survival in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 29:2071–2076

Agnelli G, George DJ, Kakkar AK et al (2012) Semuloparin for thromboprophylaxis in patients receiving chemotherapy for cancer. N Engl J Med 366:601–609

Nevitt SJ, Marson AG, Davie B et al (2017) Exploring changes over time and characteristics associated with data retrieval across individual participant data meta-analyses: systematic review. BMJ 357:j1390

Voysey M, Pollard AJ, Perera R et al (2016) Assessing sex-differences and the effect of timing of vaccination on immunogenicity, reactogenicity and efficacy of vaccines in young children: study protocol for an individual participant data meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open 6:e011680

Voysey M, Kelly DF, Fanshawe TR et al (2017) The influence of maternally derived antibody and infant age at vaccination on infant vaccine responses: an individual participant meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 171:637–646

Voysey M, Pollard AJ, Sadarangani M et al (2017) Prevalence and decay of maternal pneumococcal and meningococcal antibodies: a meta-analysis of type-specific decay rates. Vaccine 13:5850–5857

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2015) Ethical guidelines for medical and health research involving human subjects. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-10600000-Daijinkanboukouseikagakuka/0000080278.pdf. Accessed October 2017

Acknowledgements

This work was supported, in part, by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 15617613 and the non-profit organization ECRIN (“Epidemiological and Clinical Research Information Network”).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Takuya Kawahara has nothing to declare. Musashi Fukuda is an employee of Astellas Pharma. Koji Oba has received honoraria from Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd., Bristol-Myers Squibb Company Ltd., Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., and Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. Junichi Sakamoto has received a consulting fee from Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. and honoraria from Tsumura Co. Ltd. as remuneration for a lecture. Marc Buyse is an employee and shareholder of IDDI.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Kawahara, T., Fukuda, M., Oba, K. et al. Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials in the era of individual patient data sharing. Int J Clin Oncol 23, 403–409 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-018-1237-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-018-1237-z