Abstract

Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials is considered to be the methodology that provides the most solid scientific basis for constructing clinical guidelines. It involves systematically collecting the results of similar studies that were conducted to verify similar medical hypotheses and combining these results statistically. In meta-analysis, targeting only those randomized controlled trials with good comparability also provides the meta-analysis with comparability. With the combining of multiple studies and the increased sample size, meta-analysis provides results with higher clarity than those obtained from a single study. In conventional meta-analyses, in addition to estimating the combined effect, the cause of heterogeneity of the effects among studies is usually explored. If multiple studies reveal homogeneous effects, the overall effect is interpretable and generalizability can be suggested; that is, the results can be reproducible even when the study conditions are slightly modified. On the other hand, if the effect cannot be viewed as homogeneous among the studies, it is difficult to interpret the overall effect obtained from a meta-analysis. From the viewpoints of clarity, comparability, and generalizability, meta-analysis and large-scale clinical trials can provide the most valuable evidence among several possible study designs. In this article, the role of meta-analysis in cancer clinical trials is illustrated with the example of adjuvant therapy with UFT in patients with curatively resected rectal cancer, compared with the example of a large-scale clinical trial using oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Pearson K (1904) Report on certain enteric fever inoculation statistics. BMJ 3:1243–1246

Lee WL, Bausell RB, Berman BM (2001) The growth of health-related meta-analyses published from 1980 to 2000. Eval Health Prof 24:327–335

Whitehead A (2002) Meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. John Wiley and Sons, New York

Sutton AJ, Higgins JPT (2008) Recent developments in meta-analysis. Stat Med 27:625–650

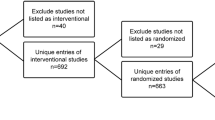

Sakamoto J, Hamada C, Kodaira S, et al. (2007) An individual patient data meta-analysis of adjuvant therapy with uracil-tegafur (UFT) in patients with curatively resected rectal cancer. Br J Cancer 96–8:1170–1177

André T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, et al. (2004) Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med 350–23:2343–2351

Kodaira S, Kikuchi K, Yasutomi M, et al. (1998) Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with mitomycin C and UFT for curatively resected rectal cancer. Results from the Cooperative Project No. 7 Group of the Japanese Foundation for Multidisciplinary Treatment of Cancer. Int J Clin Oncol 3:357–364

Watanabe M, Nishida O, Kunii Y, et al. (2004) Randomized controlled trial of the efficacy of adjuvant immunochemotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy for colorectal cancer using different combinations of the intracutaneous streptococcal preparation OK-432 and the oral pyrimidines 1-hexylcarbamoyl-5-fluorouracil and uracil/tegafur. Int J Clin Oncol 9:98–106

Kato T, Ohashi Y, Nakazato H, et al. (2002) Efficacy of oral UFT as adjuvant chemotherapy to curative resection of colorectal cancer: multicenter prospective randomized trial. Langenbecks Arch Surg 386:575–581

Akasu T, Moriya Y, Ohashi Y, et al. (2006) Adjuvant chemotherapy with uracil-tegafur for pathological stage III rectal cancer after mesorectal excision with selective lateral pelvic lymphadenectomy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Jpn J Clin Oncol 36:237–244

Freedman LS (1982) Tables of the number of patients required in clinical trials using the log-rank test. Stat Med 1:121–129

Schoenfeld D (1981) The asymptotic properties of nonparametric tests for comparing survival distributions. Biometrika 68:316–319

Gill S, Loprinzi CL, Sargent DJ, et al. (2003) Using a pooled analysis to improve the understanding of adjuvant therapy (AT) benefit for colon cancer (CC). Prog Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 22:253

Rothstein HR, Sutton AJ, Borenstein M (2005) Publication bias in meta-analysis. John Wiley and Sons, New York

Simes RJ (1987) Confronting publication bias: a cohort design for meta-analysis. Stat Med 6:11–29

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Hamada, C. The role of meta-analysis in cancer clinical trials. Int J Clin Oncol 14, 90–94 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-008-0876-x

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-008-0876-x