Abstract

Several studies through the years have proven how an unhealthy nutrition, physical inactivity, sedentary lifestyle, obesity, and smoking represent relevant risk factors in cancer genesis. This study aims to provide an overview about the relationship between meningiomas and food assumption in the Mediterranean diet and whether it can be useful in meningioma prevention or it, somehow, can prevent their recurrence. The authors performed a wide literature search in PubMed and Scopus databases investigating the presence of a correlation between Mediterranean diet and meningiomas. The following MeSH and free text terms were used: “Meningiomas” AND “Diet” and “Brain tumors” AND “diet.” Databases’ search yielded a total of 749 articles. After duplicate removal, an abstract screening according to the eligibility criteria has been performed and 40 articles were selected. Thirty-one articles were excluded because they do not meet the inclusion criteria. Finally, a total of 9 articles were included in this review. It is widely established the key and protective role that a healthy lifestyle and a balanced diet can have against tumorigenesis. Nevertheless, studies focusing exclusively on the Mediterranean diet are still lacking. Thus, multicentric and/or prospective, randomized studies are mandatory to better assess and determine the impact of food assumptions in meningioma involvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Healthy nutrition and lifestyle have certainly a crucial role in the prevention of cardiovascular, chronic-degenerative, immune-inflammatory, and tumor-related diseases: according to the World Cancer Research Fund, adopting a healthier lifestyle could have an impact on the onset of 3–4 million cancer cases worldwide.

The term Mediterranean diet, proposed by Keys et al., was based on the observations of a lower rate of cardiovascular disease in the countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea (Cyprus, Greece, and Italy) than in the Netherlands, the USA, and Finland [1] Typical features of Mediterranean diet are a high consumption of vegetables, legumes, fresh fruit, non-refined cereals, nuts, and olive oil, in association with a moderate intake of fish, milk products and ethanol, and red wine consumed during the main meals; lastly, according to the diet, red meat consumption is limited to lowered quantities [2].

Over the years, several studies have shown how a balanced diet could represent an effective preventive measure, proving that an unhealthy nutrition, physical inactivity, sedentary lifestyle, obesity (consequence of a healthy or unhealthy lifestyle), and smoking constitute relevant risk factors in cancer onset [3,4,5].

Even though the association between cancer and diet has been extensively debated, emphasizing how nutrition plays an essential role, both negatively or positively, in cancer development and/or progression, there are not enough studies focusing on its role and effect on cerebral tumors, in particular on meningiomas.

Aims

This study aims to present an overview about the relationship between meningiomas and the Mediterranean diet and whether the Mediterranean diet can be useful in meningioma prevention or in the prevention of their recurrence.

Sources

Study selection

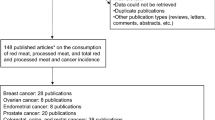

We performed a broad literature search in PubMed investigating the presence of a correlation between Mediterranean diet and meningiomas. Recorded studies were exported to Mendeley software. Only articles in English language were included. All the duplicates were removed, and a manual search was also performed to identify eventual additional studies of the reference sections. Two reviewers (U.E.B. and L.M.C.) independently screened the titles, abstracts, and full manuscripts; then, the results were analyzed and combined. The following MeSH and free text terms were identified “Meningiomas” AND “Diet” (24 articles) and “Brain tumors” AND “diet” (725 articles).

Taking into account the first MeSH term, an evaluation of studies with a temporal range from 1983 to 2022 was performed. For what it concerns the second MeSH term, the temporal range was from 1962 to 2022.

Eligibility criteria

The articles were selected according to the following inclusion criteria:

-

Full articles in English

-

Studies regarding Mediterranean diet, although not directly mentioned but containing foods from the Mediterranean diet

-

Studies regarding meningiomas

The following are the exclusion criteria:

-

Studies about diet others than Mediterranean one

-

Studies reporting other brain tumors, without mentioning or talking about meningiomas

-

Articles not in English language

-

Studies including animals

-

Studies regarding the pediatric population

According to the criteria above, all articles were identified independently by two reviewers (U.E.B. and L.M.C.) and then the results combined. The extracted data included authors, year, study design, number of patients included, type of food evaluated, the aim of the article, and the results obtained by the authors.

Our search yielded a total of 749 articles. After duplicate removal, an abstract screening according to the aforementioned eligibility criteria has been performed, and 40 articles were selected. Thirty-one articles were excluded because they do not meet the inclusion criteria. A total of 9 articles were included in the present review.

In the studies included, 509513 patients were evaluated. Among them, 7540 (1,47%) were affected by malignant brain tumor, 943 (12,5%) by meningiomas and, finally, 2637 (34,97%) were healthy controls. Study characteristics are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

It must be noticed that not univocal results can be obtained due to data fragmentation and lack of specific data about tumor histotypes.

Discussion

The Mediterranean diet: its role against cancer

Tumors represent the second leading cause of death worldwide; they recognize complex multifactorial pathophysiological mechanisms, including oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, alterations in cell cycle regulation, and dysregulation of pro-oncogenes, which result from the combination of endogenous and exogenous conditions. Among the environmental factors, one of the most important is represented by nutrition, which can influence, both negatively or positively, some cellular and molecular characteristics related to cancer.

The Mediterranean diet is probably the best known healthy dietary pattern, characterized by a high intake of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory nutrients, including olive oil (as the main source of fat) and vegetables (fruits, legumes, nuts, seeds, and whole grains); a moderate intake of fish, white meats, eggs, dairy products, and red wine; and reduced consumption of red meats. Its protective effects are well documented in several chronic diseases, such as atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, neurodegenerative and respiratory diseases, and depression, as well as for tumors, especially colon, breast, and prostate [15,16,17].

Over the years, research focused on mechanisms through which the Mediterranean diet plays a protective role in tumor development, protecting cells from the mechanism involved in tumorigenesis, such as oxidative and inflammatory processes, DNA damage, neoplastic angiogenesis, and spreading of metastases [15, 18].

The main components of the Mediterranean diet are fruits and vegetables, olive oil, fish, and red wine; they contain bioactive nutrients that counteract cell degeneration and proliferation of cancerous cells, thanks to their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, such as polyphenols, flavonoids, carotenoids, fiber, and monounsaturated fatty acids [19,20,21].

Polyphenols, the main bioactive components of the Mediterranean diet, have known anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, chemoprotective, and pro-apoptotic effects and act with complex and multiple mechanisms, including epigenetic variations, transcriptome, and expression proteins that modulate different signaling pathways (MAPK, PI3K-Akt, and Wnt/β-catenin activated by oxidative stress), thus reducing proliferation, cell migration and invasion, and angiogenesis [22,23,24]. Polyphenols can also modulate microRNAs, which regulate the expression of tumor-suppressing oncogenes or genes leading to a reduction in tumor growth and its metastatic potential [25, 26].

Flavonoids promote the elimination of pollutants (heavy metals, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, dioxins, pesticides, ultra-particulate) from tissues or mitigate their effects [27].

Several nutrients of the Mediterranean diet can modify the epigenome (which regulates the modulation of gene expression as studied by nutrigenomics), inhibiting the development of tumors and acting as protective factors [28]; this effect can be partly explained by the ability to support an effective repair of DNA damage, modulating the activity of histones and RNA methyl marker [29]. A high adherence to the Mediterranean diet has a protective role against metabolic and oxidative DNA damage, improving the antioxidant system, as demonstrated by the reduced levels of oxo-708-dihydro-20-deoxyguanosine and the increase in those of HDL-cholesterol and glutathione peroxidase [30].

Many natural compounds contained in the Mediterranean diet counteract angiogenesis, which plays an essential role in tumor growth and in the development of metastases. The Mediterranean diet inhibits the development of the metastatic phenotype in cancer cells and, also, alterations in physiological bone remodeling [31, 32].

Literature review of the most prestigious studies about cancers and Mediterranean diet

At the end of the 1950s, the “Seven Countries of Cardiovascular Diseases Study” enrolled, at entry, 16 population cohorts in eight nations of seven countries for a total of 12,763 men (aged 40–59); the aim of this epidemiological study was to highlight dietary cultural contrasts and to compare cardiovascular disease rates, related to diet differences. The findings revealed by this study allowed to point the so-called “Mediterranean diet” and showed a significant protective effect of this dietary pattern on tumors [33].

Since then, several retrospective case–control studies refined this concept and documented on a larger scale the beneficial effects of this dietary pattern in tumor prevention and progression through some parameters and scores, such as the Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) and the alternate MD score (aMED). Among them, strong evidence come from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition Study (EPIC study), which included 476,160 subjects recruited in 10 European countries from 1991 to 2001, with a mean follow-up of 13.9 years. In a systematic review of 110 high-quality studies on the EPIC cohort, fruit and vegetable consumption showed a protective effect against colorectal, mammary, and pulmonary neoplasms, and fruit only showed a protective effect on prostate cancer; high fish consumption was related to a lower risk of colorectal cancer (and fatty fish with lower risk of breast cancer), and calcium and yogurt intake was protective against colorectal and prostate cancer. Overall, adherence to the Mediterranean diet was protective against colorectal and mammary neoplasms [34].

Another example is given by the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study, which included 86,090 women with a mean follow-up of 17 years and proved that high levels of aMED score were protective for the development of squamous cell carcinomas [35]. In the Nurses’ Health Study, which enrolled 29,474 women, patients most adherent to aMED showed a lower risk of colorectal adenoma, especially of high-risk subtypes [36]. In an average 18-year follow-up of 2966 participants in the Framingham Offspring Study, women with moderate or high adherence to the Mediterranean diet showed a 25% lower risk of neoplasms than those with lower adherence, and the benefits were even better in normal weight subjects; the association was weaker in men, except in non-smokers [37].

Prospective studies and Mediterranean diet

The protective role of Mediterranean diet in tumor prevention is then well established; however, less is known about the role of diet in tumor progression in patients with an already established diagnosis of neoplasm [38]. In this regard, in a prospective study of 80 patients affected by colorectal cancer, Acevedo et al. found that high adherence to the Mediterranean diet was associated with less severe histological degrees and lower presence of synchronous adenomas [30]. Moreover, in the Multiethnic Cohort Study were enrolled 6370 patients, finding a better aMED scores associated with lower risks of mortality and cancer [39].

Mediterranean diet and meningiomas

Spotlight on brain tumors, meningiomas represent the most common primary intracranial tumors, and they overall account about 36% of all CNS lesions [40]. They are usually benign lesions (WHO I), showing a slow and non-infiltrating growth, whereas only about 19% are histologically aggressive and rapidly growing (WHO II & III). Incidence is age-related (peak at 75–84 years old age group) and about threefold higher in females (2.27:1 F:M ratio) [41, 42].

Thus far, the only well-recognized epidemiologic risk factors for these tumors are the exposure to ionizing radiation and genetic syndromes (such as the neurofibromatosis II); over the years, several foregoing epidemiologic researches have provided partial evidence in a correlation between dietary habits—in particular nitrites and nitrates exposure—and an increased risk of developing primary brain tumors, including meningiomas [43].

N-Nitroso compounds (NOCs) are distributed among food in different concentrations in the form of as N-nitrosamines and N-nitrosamides, secondary amines and amides which, endogenously, can be transformed into some metabolites called ethylnitrosoureas, in the presence of nitrite [12, 44]. The largest dietary sources of nitrosamines have been noted to be cured meat, namely the addition of salt, sugar nitrite and/or nitrate, and other compounds to meat-based products for the purpose of preservation, appearance, and flavor improvement. Overall, these molecules are deemed to be potential carcinogens in the development of brain tumors, based on evidence from animal studies [12, 44, 45].

Quite the opposite, the nutritional intake of nitrosation inhibitors, like vitamins C and E, which are commonly found in some fruits and vegetables, may relate to a reduced risk of developing the above-mentioned tumors [42].

This awareness is suggested by different studies. Kaplan et al., indeed, in a case control study (59 malignant primary brain tumors and 80 meningiomas) have showed that high protein intake is strictly related to brain tumor development [8]. Preston-Martin et al. [46], in several population-based case–control series, found an increased risk in brain meningioma development in women with high level consumption of nitrite-cured meat, even though the same correlation appeared unclear in a population composed only by men [47]. The same authors also found that the assumption of citrus fruit was slightly protective against meningiomas [48]. Similarly, Burch et al. [49]suggested a protective role of fruits, but not of vegetables, in the genesis of primary brain tumors; they did not find a significant relationship with the nutritional intake of processed meat. The role of vitamins C and E in brain’s tumorigenesis inhibition was also confirmed by Mirvish [50] and Hu et al. [9], even if Boeing et al. [6] did not confirm the aforementioned association in their series. Moreover, Huncharek and Kupelnick [51] in their meta-analysis, alongside with previous epidemiologic studies, suggested a possible correlation between maternal consumption of cured meat and an increased risk of pediatric brain tumor development.

Finally, Dimitropoulou et al. [11], in a case control study, highlighted that a diet rich in zinc seems to be related to a lower risk of meningioma development, even if a correlation with glioma has not been proved yet.

In order to stick on the subject of food intake and correlative risk of developing brain tumors, previous literature on this field has proven that also metabolic disorders are strongly linked to the development of primary brain tumors.

Currently, as far as our knowledge goes, there is substantial evidence in the role of obesity and poor physical activity in increasing meningioma risk [10, 52,53,54]: obesity is associated with the development of type II diabetes and so higher circulating levels of IGF-1 and insulin, which can pass through the blood–brain barrier and thus promote, through several mechanism, meningioma’s growth and progression [52,53,54,55,56,57] Moreover, a higher concentration of adipose tissue is deemed to be associated with a major blood concentration of estrogens, which could therefore lead to the development and progression of meningiomas. Interestingly, this awareness could partially explain the higher incidence of these tumors among the female gender [53].

The results of our research are consistent with the hypothesis that carcinogens contained in some categories of food, and the amount of food itself may be involved into brain tumor etiology, suggesting that a combination of N-nitroso compounds (NOCs) and other supplements consumed from diet may be involved with brain tumors’ carcinogenesis.

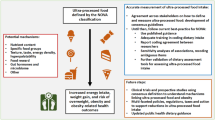

Conclusions

It is widely accepted the key and protective role that a healthy lifestyle and a balanced diet can have against tumorigenesis. The Mediterranean diet contains many nutrients counteracting angiogenesis and safeguarding from tumor development. Currently, several studies have discussed its protective role focusing on colorectal, mammary, and pulmonary tumors, not extensively mentioning primary brain tumor. According to preliminary results retrieved from this overview, some categories of food, belonging to the Mediterranean diet, have shown a protective role in brain’s tumorigenesis. Nevertheless, papers focused just on the Mediterranean diet are still lacking.

Thus, multicentric and/or prospective and randomized studies are mandatory to better assess and determine the impact of dietary intake in meningioma risk.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Keys A et al (1986) The diet and 15-year death rate in the seven countries study. Am J Epidemiol 124:903–915

Jacobs DR Jr, Gross MD, Tapsell LC (2009) Food synergy: an operational concept for understanding nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 89(5):1543S-1548S. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736B

Donaldson MS (2004) Nutrition and cancer: A review of the evidence for an anti-cancer diet. Nutr J 3:19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-3-19

Vineis P, Wild CP (2014) Global cancer patterns: causes and prevention. Lancet 383(9916):549–557. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62224-2

Trichopoulou A, Critselis E (2004) Mediterranean diet and longevity. Eur J Cancer Prev 13(5):453–456. https://doi.org/10.1097/00008469-200410000-00014

Boeing H, Schlehofer B, Blettner M, Wahrendorf J (1993) Dietary carcinogens and the risk for glioma and meningioma in Germany. Int J Cancer 53:561–565

Guo W, Linet MS, Chow W, Li J, Blot WJ (1994) Diet and serum markers in relation to primary brain tumor risk in China. Nutr Cancer 22:143–150

Kaplan S, Novikov I, Modan B (1997) Nutritional factors in the etiology of brain tumors potential role of nitrosamines, fat, and cholesterol. Am J Epidemiol 146:832–841

Hu J et al (1999) Diet and brain cancer in adults: a case-control study in northeast China. Int J Cancer 81:20–23

Bansal N, Dawande P, Shukla S, Acharya S (2020) Effect of lifestyle and dietary factors in the development of brain tumors. J Fam Med Prim Care 9:5200–5204

Dimitropoulou P et al (2008) Dietary zinc intake and brain cancer in adults: a case–control study. Br J Nutr 99:667–673

Terry MB et al (2009) An international case-control study of adult diet and brain tumor risk: a histology-specific analysis by food group. Ann Epidemiol 19:161–171

Allès B et al (2016) Dietary and alcohol intake and central nervous system tumors in adults: results of the CERENAT multicenter case-control study. Neuroepidemiology 47:145–154

Lian W, Wang R, Xing B, Yao Y (2017) Fish intake and the risk of brain tumor: a meta-analysis with systematic review. Nutr J 16:1

Mentella MC, Scaldaferri F, Gasbarrini A, Miggiano GAD (2019) Cancer and Mediterranean Diet: A Review. Nutr 11(9):2059. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092059

Dominguez LJ, Di Bella G, Veronese N, Barbagallo M (2021) Impact of Mediterranean Diet on Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases and Longevity. Nutr 13(6):2028. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13062028

Dilnaz F, Zafar F, Afroze T et al (2021) Mediterranean Diet and Physical Activity: Two Imperative Components in Breast Cancer Prevention. Cureus 13(8):e17306. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.17306

Augimeri G, Bonofiglio D (2021) The Mediterranean Diet as a Source of Natural Compounds: Does It Represent a Protective Choice against Cancer? Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 14(9):920. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14090920

Mattioli AV, Serra F, Spatafora F, Toni S, Farinetti A, Gelmini R (2022) Polyphenols, Olive oil and Colonrectal cancer: the effect of Mediterranean Diet in the prevention. Acta Biomed 92(6):e2021307. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v92i6.10390

Issaoui M et al (2020) Phenols, flavors, and the Mediterranean diet. J AOAC Int 103:915–924

Farràs M et al (2021) Beneficial effects of olive oil and Mediterranean diet on cancer physio-pathology and incidence. Semin Cancer Biol 73:178–195

Sain A, Sahu S, Naskar D (2022) Potential of olive oil and its phenolic compounds as therapeutic intervention against colorectal cancer: a comprehensive review. Br J Nutr 128(7):1257–1273. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114521002919

Moral R, Escrich E (2022) Influence of Olive Oil and Its Components on Breast Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms. Mol 27(2):477. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27020477

Majumder D et al (2022) Olive oil consumption can prevent non-communicable diseases and COVID-19: a review. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 23:261–275

Benot-Dominguez R, Tupone MG, Castelli V et al (2021) Olive leaf extract impairs mitochondria by pro-oxidant activity in MDA-MB-231 and OVCAR-3 cancer cells. Biomed Pharmacother 134:111139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2020.111139

Zabaleta ME, Forbes-Hernández TY, Simal-Gandara J et al (2020) Effect of polyphenols on HER2-positive breast cancer and related miRNAs: Epigenomic regulation. Food Res Int 137:109623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109623

Montano L, Maugeri A, Volpe MG et al (2022) Mediterranean Diet as a Shield against Male Infertility and Cancer Risk Induced by Environmental Pollutants: A Focus on Flavonoids. Int J Mol Sci. 23(3):1568. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23031568

Divella R, Daniele A, Savino E, Paradiso A (2020) Anticancer effects of nutraceuticals in the Mediterranean diet: an epigenetic diet model. Cancer Genomics Proteomics 17:335–350

De Polo A, Labbé DP (2021) Diet-dependent metabolic regulation of DNA double-strand break repair in cancer: more choices on the menu. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 14:403–414

Acevedo-León D, Gómez-Abril SÁ, Monzó-Beltrán L et al (2022) Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Has a Protective Role against Metabolic and DNA Damage Markers in Colorectal Cancer Patients. Antioxid (Basel). 11(3):499. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11030499

Maroni P, Bendinelli P, Fulgenzi A, Ferraretto A (2021) Mediterranean Diet Food Components as Possible Adjuvant Therapies to Counteract Breast and Prostate Cancer Progression to Bone Metastasis. Biomol 11(9):1336. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom11091336

Pang S, Jia M, Gao J, Liu X, Guo W, Zhang H (2021) Effects of dietary patterns combined with dietary phytochemicals on breast cancer metastasis. Life Sci 264:118720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118720

Menotti A, Puddu PE, Catasta G (2022) Dietary habits, cardiovascular and other causes of death in a practically extinct cohort of middle-aged men followed-up for 61 years. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 32:1819–1829

Ubago-Guisado E, Rodríguez-Barranco M, Ching-López A et al (2021) Evidence Update on the Relationship between Diet and the Most Common Cancers from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) Study: A Systematic Review. Nutr 13(10):3582. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103582

Myneni AA et al (2021) Indices of diet quality and risk of lung cancer in the women’s health initiative observational study. J Nutr 151:1618–1627

Zheng X et al (2021) Comprehensive assessment of diet quality and risk of precursors of early-onset colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 113:543–552

Yiannakou I, Singer MR, Jacques PF, Xanthakis V, Ellison RC, Moore LL (2021) Adherence to a Mediterranean-Style Dietary Pattern and Cancer Risk in a Prospective Cohort Study. Nutr 13(11):4064. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13114064

Wiseman MJ (2019) Nutrition and cancer: prevention and survival. Br J Nutr 122:481–487

Park SY, Boushey CJ, Shvetsov YB et al (2021) Diet Quality and Risk of Lung Cancer in the Multiethnic Cohort Study. Nutr 13(5):1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13051614

Achey RL et al (2019) Nonmalignant and malignant meningioma incidence and survival in the elderly, 2005–2015, using the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States. Neuro Oncol 21:380–391

Buerki RA et al (2018) An overview of meningiomas. Futur Oncol 14:2161–2177

Brunasso L et al (2022) A spotlight on the role of radiomics and machine-learning applications in the management of intracranial meningiomas: a new perspective in neuro-oncology: a review. Life (Basel, Switzerland) 12(4):586. https://doi.org/10.3390/life12040586

Pouchieu C et al (2016) Descriptive epidemiology and risk factors of primary central nervous system tumors: current knowledge. Rev Neurol (Paris) 172:46–55

Preston-Martin S, Henderson BE (1984) N-nitroso compounds and human intracranial tumours. IARC Sci Publ 57:887–894

Forrest ARW (1993) Chemistry and Biology of N-nitroso Compounds. Cambridge Monographs on Cancer Research. J Clin Pathol 46(1):95

Preston-Martin S et al (1980) Case-control study of intracranial meningiomas in women in Los Angeles County, California. J Natl Cancer Inst 65(1):67–73

Preston-Martin S et al (1983) Risk factors for meningiomas in men in Los Angeles County. J Natl Cancer Inst 70(5):863–866

Preston-Martin S et al (1989) Risk factors for gliomas and meningiomas in males in Los Angeles County. Can Res 49(21):6137–6143

Burch JD et al (1987) An exploratory case-control study of brain tumors in adults. J Natl Cancer Inst 78(4):601–609

Mirvish SS (1986) Effects of vitamins C and E on N-nitroso compound formation, carcinogenesis, and cancer. Cancer 58(8 Suppl):1842–1850

Huncharek M, Kupelnick B (2004) A meta-analysis of maternal cured meat consumption during pregnancy and the risk of childhood brain tumors. Neuroepidemiology 23:78–84

Bernardo BM et al (2016) Association between prediagnostic glucose, triglycerides, cholesterol and meningioma, and reverse causality. Br J Cancer 115:108–114

Niedermaier T et al (2015) Body mass index, physical activity, and risk of adult meningioma and glioma: a meta-analysis. Neurology 85:1342–1350

Bharadwaj S et al (2015) Serum lactate as a potential biomarker of non-glial brain tumors. J Clin Neurosci 22:1625–1627

Giammalva GR et al (2022) The long and winding road: an overview of the immunological landscape of intracranial meningiomas. Cancers 14(15):3639

Rajaraman P (2011) Hunting for the causes of meningioma–obesity is a suspect. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 4:1353–1355

Almanza-Aguilera E et al (2023) Mediterranean diet and olive oil, microbiota, and obesity-related cancers. From mechanisms to prevention. Semin Cancer Biol 95:103–119

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Palermo within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C., R.M., and I.S.; methodology, S.M.; software, U.E.B.; validation, A.T., R.M, and A.A.; formal analysis, L.M.C.; investigation, A.S. and K.G.; resources, V.A. and I.B.; data curation, S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.C.; writing—review and editing, R.C. and S.M.; visualization, I.S., L.B., and D.G.I.; supervision, A.T. and R.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Costanzo, R., Simonetta, I., Musso, S. et al. Role of Mediterranean diet in the development and recurrence of meningiomas: a narrative review. Neurosurg Rev 46, 255 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-023-02128-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-023-02128-8