Abstract

Background

Surgery for perforated gastric cancer has a dual purpose: treating life-threatening peritonitis and curing gastric cancer. An emergent one-stage gastrectomy may place an undue burden on patients with a poor general status and could impair long-term survival even if the gastric malignancy is curable. A two-stage gastrectomy, in which the initial treatment of peritonitis is followed by elective gastrectomy, can accomplish both desired purposes.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed 514 Japanese cases of perforated gastric cancer. 376 patients underwent a one-stage gastrectomy and 54 patients underwent a two-stage gastrectomy. We evaluated patient characteristics, surgical outcomes, postoperative complications, and survival rates in both groups.

Results

The two-stage gastrectomy group saw a 78.4 % rate of curative R0 resection and 1.9 % hospital mortality rate, while corresponding rates in the one-stage gastrectomy group were 50 and 11.4 %, respectively. Among cases in which curative R0 resection was performed, there was no significant difference in overall survival between 136 one-stage gastrostomies and 40 two-stage gastrostomies. In a multivariate analysis, curative R0 resection [hazard ratio (HR) 2.937, p = 0.001] and depth of tumor invasion (HR 1.179, p = 0.016) were identified as independent prognostic factors.

Conclusions

Regardless of whether patients underwent a one-stage or two-stage gastrectomy, curative R0 resection improved survival in patients with perforated gastric cancer. When curative R0 resection cannot be performed in the initial treatment phase due to diffuse peritonitis, non-curative and palliative gastrectomy should be avoided, and a two-stage gastrectomy should be planned following peritonitis recovery and detailed examinations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastric perforation is one of the most frequent causes of acute abdomen [1]. In general, gastrointestinal perforation is suspected based on certain clinical symptoms (e.g., abdominal rebound tenderness or muscular guarding with high-grade fever), and confirmed by imaging modalities including abdominal computed tomography (CT). When diffuse peritonitis due to gastrointestinal perforation is diagnosed, emergent surgery is necessary without further detailed preoperative examinations. The main cause for gastric perforation is gastric ulcer, but approximately 10 % of the cases are caused by gastric cancer [2]. Moreover, perforated gastric cancer is responsible for less than 1 % of cases of acute abdomen [2]. It is difficult to diagnose perforated gastric cancer, because its preoperative symptoms are the same as those of perforated gastric ulcer [3, 4]. Furthermore, it may be difficult to distinguish a gastric ulcer from gastric cancer at the time of surgery, especially if an intraoperative frozen section is unavailable, except in cases with obvious metastatic tumors [5].

The diagnosis and treatment of perforated gastric cancer is difficult. At one time, emergent one-stage gastrectomies were generally performed for gastric perforation with diffuse peritonitis, regardless of whether the disease was benign or malignant [6]. One-stage gastrectomy, however, was found to be associated with high mortality rates (0–50 %) [6]. Moreover, sufficient lymph node dissection is difficult to achieve during an emergent surgery for perforated gastric cancer, which may impair long-term survival due to recurrence [6]. In patients with a poor clinical condition, simple closure and omental patch repair is a suitable procedure. If the perforation was caused by cancer, however, the risk of secondary leakage due to reperforation cannot be excluded [7]. Therefore, a standard surgical treatment for perforated gastric cancer has not been established, and the surgical approach is decided on a patient-by-patient basis, depending on the extensiveness of gastric malignancy and degree of peritonitis.

In this systematic review, we analyzed the surgical treatment outcomes of perforated gastric cancer in Japanese cases. We particularly focused on the differences between the surgical approaches of the one-stage gastrectomy and the two-stage gastrectomy.

Materials and methods

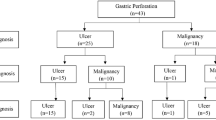

A search of the Japanese literature for case reports was conducted in the ICHUSHI-Web database (Japan Medical Abstract Society) from 1983 to 2009, complemented by manual searches of references from relevant articles from 1979 onwards where necessary. Search terms included “Gastric Cancer” and/or “Perforation”, excluding cases described only in proceedings and iatrogenic gastric perforation related to endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer. In case of multiple publications or overlapping data sets, only cases from the most recent reports were analyzed. A total of 514 cases (115 case reports in Japan) of perforated gastric cancer reported in the Japanese literature were extracted and used for the analysis [8–122] (Fig. 1). In each case, patient characteristics, the timing of the surgical treatment, operative procedure, curability, hospital mortality, and postoperative survival were examined. Absent data in individual cases were treated as missing values and excluded. The depth of invasion (T-factor), lymph node metastasis (N-factor), peritoneal dissemination (P-factor), area of regional lymph node dissection (D-number), staging, tumor location (U, upper region; M, middle region; L, lower region), and histological classification were determined on the basis of the General Rules for the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma, 13th Japanese edition and 2nd English edition [123]. The Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) R-factor was applied for quantification: no residual cancer (R0), microscopically residual cancer (R1), and macroscopically residual cancer (R2), respectively.

Pearson’s Chi square test and the Mann–Whitney U test were used for statistical analysis. The Kaplan–Meier method was used for survival analysis and the log-rank test was used to examine significant differences. A multivariate analysis, using the Cox proportional hazards model, was performed to assess the influence of clinicopathological variables on death. Statistical significance was defined as a p value < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed by using Dr. SPSS II for Windows (Statistical Package for Social Science, release 11.0.1J, SPSS Japan Inc, Tokyo, Japan).

Results

Classification of the cases

The treatment courses of all 514 cases were classified as shown in Fig. 1. Initial conservative treatment was performed in 12 of the 514 cases, because peritonitis was limited and subsequent elective gastrectomy could be planned following peritonitis recovery. After recovering from peritonitis, 10 of the 12 cases underwent gastrectomy (classified as the two-stage gastrectomy group, Fig. 1). Among the 502 perforated gastric cancer patients in whom emergent surgery was the initial treatment, precise records on the timing of perforated gastric cancer diagnosis were available in 355 cases; out of those, 158 cases (44.5 %) were diagnosed by examining preoperative clinical findings; 106 cases (29.9 %) by examining the intraoperative surgical findings; and 91 cases (25.6 %) by postoperative detailed examination after the initial surgery. Of the 502 cases treated with emergent surgery, 388 cases underwent gastrectomy and 114 cases underwent simple closure or omental patch repair. Among the 388 cases treated with gastrectomy, 376 gastrectomies were completed in one stage (classified as the one-stage gastrectomy group, Fig. 1) and 12 cases required a second surgery for additional resection of the stomach or regional lymph nodes (classified as the two-stage gastrectomy group, Fig. 1). Of the 114 cases treated by performing simple closure or omental patch repair at the initial surgery, 76 received no additional surgical treatment due to insufficient recovery from diffuse peritonitis or detection of non-curative factors such as a locally advanced invasive tumor or obvious metastasis. A second surgery was attempted in the remaining 38 cases. Secondary gastrectomy was performed in 32 of these 38 cases (classified as the two-stage gastrectomy group, Fig. 1), but not in the remaining 6 cases because of advanced stage disease with adjacent organ invasion or diffuse peritoneal metastasis. Overall, the two-stage gastrectomy group (n = 54) comprised 10 cases of gastrectomy following conservative treatment, 12 cases treated with additional resection of the stomach or regional lymph nodes following the initial surgery, and 32 cases of gastrectomy following initial surgical treatment by simple closure or omental patch repair (Fig. 1). Of these 54 cases, 6 were diagnosed with perforated gastric cancer before or at the initial surgery and underwent a two-stage surgery because additional resection of the proximal margin of the stomach or regional lymph nodes was needed to complete the R0 resection. In the remaining 47 cases, gastric cancer could not be diagnosed either prior to or at the initial surgery. Two-stage gastrectomy with lymph node dissection was performed in these patients after histological diagnosis in a resected specimen. Only one case was excluded because the reason for the second surgery was unclear.

Characteristics of the two groups

Although gender, tumor location, and histological classification were equally distributed between the two groups, the one-stage gastrectomy group showed older patients (p < 0.001), greater invasiveness in terms of the T-factor, an indicator of the depth of tumor invasion (p = 0.010), and more advanced Stage grouping (p < 0.001) than the two-stage gastrectomy group (Table 1). The one-stage gastrectomy group also tended to show greater invasiveness in terms of the N-factor, an indicator of lymph node metastasis (p = 0.054), and the P-factor, an indicator of peritoneal dissemination (p = 0.071) (Table 1).

Surgical treatment outcomes

The rate of curative R0 resection was 50 % in the one-stage gastrectomy group (Table 2). Among the 268 cases in the one-stage gastrectomy group who had precise records of lymph node dissection, D0 dissection was performed in 100 cases (37.3 %), D1 dissection in 91 cases (34.0 %), and D2 or D3 dissection in 77 cases (28.7 %). In the two-stage gastrectomy group, the rate of curative R0 resection was 78.4 % (Table 2). D0 lymph node dissection was performed in 5 cases (10 %), D1 in 9 cases (18 %), and D2 or D3 in 36 cases (72 %). The rates of R0 resection (p < 0.001) and D2 lymph node dissection (p < 0.001) were significantly higher in the two-stage gastrectomy group.

Of the 376 one-stage gastrectomy cases, postoperative hospital death occurred in 42 cases, with a mortality rate of 11.4 % (Table 2). Among the 42 cases with postoperative hospital death, 7 cases were after R0 resection, 21 cases were after R1/2 resection, and the remaining 14 cases were not classified due to the lack of description. Of the 54 two-stage gastrectomy cases, only one case experienced anastomotic leakage at the esophagojejunostomy after initial total gastrectomy. After recovering from this complication, the case underwent additional lymph node dissection as a secondary surgery. Two cases experienced anastomotic leakage at the esophagojejunostomy after the second surgery. One case underwent additional total resection of the remnant stomach following distal gastrectomy, and another case underwent total gastrectomy following omental patch repair. In the two-stage gastrectomy group, postoperative hospital death occurred in only one case due to acute respiratory distress syndrome after two-stage total gastrectomy following omental patch repair, and the mortality rate was therefore 1.9 % (Table 2), which was significantly lower than the mortality rate in the one-stage gastrectomy group (p = 0.010).

Survival and prognosis

The survival rate of the 176 cases with curative R0 resection (136 cases from the one-stage gastrectomy group and 40 cases from the two-stage gastrectomy group) significantly exceeded that of the 147 cases with non-curative R1 and 2 resections (136 cases from the one-stage gastrectomy group and 11 cases from the two-stage gastrectomy group) (p < 0.001, Fig. 2). There was no significant difference in the survival rates of the R0 resection cases between the one-stage and the two-stage gastrectomy groups (p = 0.300, Fig. 3). Likewise, no survival differences were identified between the two surgical approaches with regards to non-curative R1 and 2 resections (p = 0.128, Fig. 4).

Prognostic factors were analyzed in 430 patients who underwent gastrectomy, including both the one-stage and two-stage gastrectomy groups. In a multivariate analysis, curability (hazard ratio (HR) = 2.937, p = 0.001) and T-factor (HR = 1.179, p = 0.016) were significant factors, whereas no significant difference was observed for surgical treatment (Table 3).

Discussion

Perforated gastric cancer is rare, accounting for less than 5 % of all gastric cancers [3, 7]. The disease is not only rare, but also difficult to diagnose before and at surgery. Generally, when emergent surgery was performed, detailed examinations for gastric cancer could not be conducted preoperatively, as patients were in poor systemic condition due to diffuse peritonitis. Furthermore, it is difficult to distinguish between a benign gastric ulcer and gastric cancer, because inflammatory changes associated with peritonitis resemble those caused by invasion of a local tumor and lymph node metastases [5]. In many emergent surgeries, detailed examinations such as intra-operative histological diagnoses by using frozen sections or intra-operative endoscopy could not be performed. The preoperative diagnostic rate in perforated gastric cancer has been reported to be 29–57 % [4, 124].

Surgical treatment for perforated gastric cancer has two opposing purposes. One is as a life-saving and damage-control surgery for diffuse peritonitis and the other is the removal of malignant tissues without leaving residual parts behind. Even if gastric cancer can be successfully diagnosed preoperatively or intra-operatively, it is still difficult to determine the optimal treatment. Thus, suitable treatment should be planned depending on the severity of peritonitis, stage of malignancy, presence of comorbidity, and curability in each case.

It had been thought that such patients could be rescued and offered good palliation by emergent one-stage gastrectomy [4, 125, 126]. One-stage radical gastrectomy with possible extensive lymphadenectomy was recommended, if permitted by the patient’s general condition, because if treated with only simple closure or omental patch repair, tissue fragility and poor healing in the surrounding tissue might result in leakage at the site of perforation [7], and severe adhesion in the peritoneal cavity could be predicted at the second surgery after the initial surgery [125]. However, in this study, we found that in the Japanese perforated gastric cancer series, one-stage gastrectomy had a high mortality rate (11.4 %) and low curative resection rate (50 %). Moreover, patients with non-curative R1/2 resection tended to show more frequent postoperative mortalities than those with curative R0 resection. These results suggest that it is necessary to reconsider the surgical indication for planned non-curative and palliative one-stage gastrectomy.

Regardless of whether one-stage or two-stage gastrectomy is employed, the most important goal of surgical treatment for perforated gastric cancer is to achieve curative R0 resection, the same as in non-perforated common gastric cancer [6]. When curative resection was possible, the median survival time was 75 months and the 5-year survival rate was about 50 % in perforated gastric cancer [6]. Several reports on perforated gastric cancer showed a significantly better prognosis for patients who underwent curative resection than those who underwent non-curative resection [5, 124, 127]. In the present analysis, the survival rate was better for patients who underwent curative R0 resection than those who underwent non-curative R1 and R2 resections, regardless of whether the surgical approach was one-stage or two-stage gastrectomy. Furthermore, multivariate analysis supported the importance of the curative R0 resection as a prognostic factor. Although curative R0 resection by one-stage gastrectomy is considered to be a necessary and sufficient procedure for achieving the dual purpose of treating peritonitis caused by gastric perforation and resecting gastric malignancy, there are many cases who did not undergo curative R0 resection at the initial surgery due to diffuse peritonitis or insufficient examinations [3]. For such cases, two-stage gastrectomy could improve the possibility of undergoing a future curative R0 resection after recovering from the diffuse peritonitis or undergoing a detailed sufficient examination including histological diagnosis.

Lehnert et al. [5] recommend that the initial surgery should be directed toward the treatment of peritonitis, and radical oncological surgery for gastric cancer should be planned following patient recovery and a histological confirmation of malignancy. In addition, they also suggested that one-stage radical gastrectomy be conducted in restricted situations, because it is difficult to predict the burden of one-stage radical gastrectomy on patients. They defined the criteria for one-stage gastrectomy as follows: (1) when gastric cancer has been diagnosed; (2) when the patient’s general condition is good and there is no risk of surgical complications; and (3) when the peritonitis is not diffuse [5]. In the present analysis of 32 cases undergoing simple closure or omental patch repair at the initial surgery, no leakage from the site of closure had occurred. In addition, the mortality rate for two-stage gastrectomy was 1.9 %. We further observed a higher proportion of patients who underwent D2 dissection and curative R0 resection in the two-stage gastrectomy group than in the one-stage gastrectomy group. Moreover, our analysis of the overall survival rates, including cases of postoperative hospital mortality, revealed similar survival rates for the 2 groups, even though the postoperative mortality rates were significantly different. One possible explanation for this was that the oncological tumor progression was better reflected in the overall survival rate than in the postoperative mortality rate. In other words, even if the patients who underwent one-stage gastrectomy overcame the postoperative complications, such as in-hospital mortality, long-term survival was not drastically better than that observed after two-stage gastrectomy. Therefore, the possible prevention of postoperative hospital death could be a reason for the selection of two-stage gastrectomy, especially in cases of diffuse peritonitis. Overall, the results of the present analysis espouse the recommendations of Lehnert et al. and suggest that two-stage gastrectomy should be taken into account to avoid non-curative R1/2 resections and decrease the risk of surgical complications, especially in the situation of diffuse peritonitis or insufficient examinations. However, we were unable to determine definitely which treatment is more suitable for perforated gastric cancer, because some patient characteristics were not equally distributed between the one-stage and two-stage gastrectomy groups. The one-stage gastrectomy group included older patients, with more invasive tumor depth, and more advanced staging than the two-stage group, as shown in Table 1.

Laparoscopic surgery has become available as a treatment for perforation of the upper gastrointestinal tract, especially in recent cases of perforated peptic ulcer [128, 129]. In our analysis, 5 of the 54 two-stage gastrectomy cases underwent laparoscopic omental patch repair at the initial surgery [101, 102, 107, 112, 115]. For perforated gastric cancer, a laparoscopic approach at the initial surgery could be useful because of the ease it provides for observing the whole abdominal cavity, which might be difficult in open laparotomy. Furthermore, a laparoscopic approach at the initial surgery can reduce tissue adhesion in the abdominal cavity and make it easier to perform a second surgery as a two-stage gastrectomy.

This retrospective analysis had some limitations. First, the degree of peritonitis, which is an essential factor for deciding on a suitable course of treatment, had not been investigated sufficiently due to the lack of available information. For the same reason, we could not fully investigate and discuss the rate and pattern of recurrence. Tsujimoto et al. [2] showed that there were no significant differences in the recurrence rate and pattern between perforated and non-perforated gastric cancer. Several other publications also showed that peritoneal contamination due to perforation did not adversely affect survival in perforated gastric cancer [5, 6, 124]. Second, uneven levels of diagnosis and treatment at different centers might have affected the results of this study. Until now, only 30 cases of perforated gastric cancer at most had been reported from a single institution [4]. Therefore, in this analysis, we collected and investigated as many cases as possible from multiple centers for a systemic view of the results. Previous multicenter analyses of numerous cases of perforated gastric cancer have not been reported. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a multicenter analysis of the treatment outcome of two-stage gastrectomy for perforated gastric cancer.

In conclusion, the most important goal for perforated gastric cancer is to achieve curative R0 resection, regardless of whether the surgical approach is a one-stage or two-stage gastrectomy. The best surgical approach for perforated gastric cancer is the one that can raise the probability of gaining curative R0 resection safely to the greatest extent, and the physician’s decision on whether to perform a one-stage or two-stage gastrectomy should be made on the basis of these perspectives. When gastric cancer can be diagnosed before or at surgery, one-stage gastrectomy should be performed in cases with limited peritonitis that can be expected to achieve curative R0 resection. However, if curative R0 resection cannot be expected due to diffuse peritonitis, it is important to avoid non-curative and palliative gastrectomy and plan treatment only for the peritonitis at the initial surgery, and then plan a two-stage gastrectomy after detailed examinations.

References

Martin RF, Rossi RL. The acute abdomen. An overview and algorithms. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77:1227–43.

Tsujimoto H, Hiraki S, Sakamoto N, Yaguchi Y, Horio T, Kumano I, et al. Outcome after emergency surgery in patients with a free perforation caused by gastric cancer. Exp Ther Med. 2010;1:199–203.

Roviello F, Rossi S, Marrelli D, De Manzoni G, Pedrazzani C, Morgagni P, et al. Perforated gastric carcinoma: a report of 10 cases and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2006;4:19.

Gertsch P, Yip SK, Chow LW, Lauder IJ. Free perforation of gastric carcinoma. Results of surgical treatment. Arch Surg. 1995;130:177–81.

Lehnert T, Buhl K, Dueck M, Hinz U, Herfarth C. Two-stage radical gastrectomy for perforated gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26:780–4.

Mahar AL, Brar SS, Coburn NG, Law C, Helyer LK. Surgical management of gastric perforation in the setting of gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15(Suppl 1):S146–52.

Ozmen MM, Zulfikaroglu B, Kece C, Aslar AK, Ozalp N, Koc M. Factors influencing mortality in spontaneous gastric tumour perforations. J Int Med Res. 2002;30:180–4.

Asanuma E, Nomura H, Higashi G, Yamamoto S, Nishi M. A study on the cases with perforation of gastric cancer -with special reference to studies on 6 cases from our clinic and 128 cases reported in japan. Med J Kagoshima Univ. 1979;31:165–73 (in Japanese).

Takei N, Ishimoto K, Kono N, Katsumi M, Yamaguchi T, Ura S. Perforated gastric carcinoma—report of 4 cases and review of the literature. J Wakayama Med Soc. 1980;31:269–76 (in Japanese).

Maeda M, Shimazu H, Kobori O, Furuta Y, Danno M, Furuyama Y, et al. Perforated gastric cancer: report of six cases and review of the Japanese literature. J Jpn Soc Clin Surg. 1981;42:647–54 (in Japanese).

Itano S, Onishi N, Kobuchi K, Onishi T, Gochi A, Gotoh K, et al. The relationship between the complications and early gastric cancers. J Med Mie Univ. 1981;25:53–7 (in Japanese).

Tamakuma S. Treatment of peritonitis due to the perforation of gastric cancer. Gastroenterol Surg. 1981;4:1527–32 (in Japanese).

Kida K, Kohno K, Soeno T, Kato E, Takahashi T. Report of a case of perforated gastric cancer in Borrmann IV. Akita J Med. 1981;7:293–5 (in Japanese).

Hashimoto K, Fukushima H, Kitasato S, Hirai Y, horiuchi M, Takeda J, et al. Study on perforated cases of gastric cancer. J Kurume Med Assoc. 1982;45:1323–8 (in Japanese).

Takagi A, Sakiyama T, Nagai H. A study on the mariner cases with gastroduodenal perforation who underwent palliative operation in foreign countries. Jpn J Marit Med. 1983;20:55–60 (in Japanese).

Toda K, Hirose S, Kataoka K, Kitamura M, Tsutsui M, Kimura H, et al. Clinical studies on operative cases of perforated gastric cancer. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 1983;16:1645–9 (in Japanese).

Ikebuchi M, Satani M, Ono N, Morita M, Matsuo Y, Tatsumi Y, et al. Perforation of gastric cancer. Med J Osaka Pref Genl Hosp. 1983;6:26–30 (in Japanese).

Kawada Y, Shimizu K, Shoji T. Gastric perforation due to gastric cancer. J Jpn Soc Clin Surg. 1983;44:403–7 (in Japanese).

Kurosu Y, Fukamachi S, Mizuno T, Morita K. Perforated gastric cancer. J Nihon Univ Med Ass. 1984;43:963–6 (in Japanese).

Nagino M, Takayanagi K, Horisawa M, Kondo S, Mori K, Tanno T. A case of perforation of early gastric cancer. J Jpn Soc Clin Surg. 1984;45:1308–12 (in Japanese).

Kanai M, Shichino S, Satoh T, Akita Y, Katoh T, Katayama M, et al. A study on perforated gastric cancer. J Yachiyo Hosp. 1984;4:33–6 (in Japanese).

Noguchi T, Saito A. Report of 2 cases of perforated gastric cancer and review of literature. Teishin Igaku. 1984;36:683–7 (in Japanese).

Kawamura T, Konaga E, Enomoto M, Sasaki A, Yagi T, Hasuoka H, et al. A study on the cases with perforation of gastric cancer—with special reference to studies on 8 cases from our clinic and 116 cases reported in Japan. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 1985;18:980–3 (in Japanese).

Muira T, Ishii T, Shimoyama T, Hirano T, Shimizu T, Fukuda A, et al. Surgical treatment for perforated gastric cancer. Surgery. 1985;47:1522–6 (in Japanese).

Ishii K, Orihata H, Kuramitsu H, Suzuki T, Shiratori T, Miyazaki K, et al. A study on the problems for initial treatment of perforated gastric cancer. KANTO J Jpn Assoc Acute Med. 1985;6:134–5 (in Japanese).

Ishibashi H, Miyata M. The surgical treatment of perforated gastric cancer. J Jpn Soc Clin Surg. 1985;46:226–32 (in Japanese).

Sano C, Kumamoto M, Kubara K, Mori M. A case report of perforated gastric cancer diagnosed before operation. Matsuyama R C Hosp J Med. 1985;9:159–63 (in Japanese).

Kitajima M, Torii H, Yoda I, Kiuchi R, Seki M, Miyake J, et al. Surgical treatment for the patients with bleeding and perforation of gastric cancer. J Clin Surg. 1985;40:343–8 (in Japanese).

Mikami Y, Ozawa M, Sugiyama Y, Hada R, Nakachi H, Fukushima T, et al. A study of perforated cases of gastric carcinoma. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 1986;19:2280–3 (in Japanese).

Nishi M, Yoshida K. Perforated gastric cancer. J Geriatric Pract. 1986;7:291–5 (in Japanese).

Sato Y, Soeda O, Fukuda Y, Harada D, Miyashita M, Yamauchi H, et al. The clinical study according to perforation of the gastric cancer. Surg Diag Treat. 1986;28:1171–4 (in Japanese).

Shibata N, Noguchi S, Tamura S, Fujimoto N, Aikawa T, Kagotani K, et al. Prognosis and treatment for perforation of early gastric carcinoma. Gastroenterol Surg. 1986;9:1163–6 (in Japanese).

Kawano M, Miura K, Hiraide H, Kanabe S, Mochizuki H, Tamaki K, et al. Study of perforated gastrointestinal malignancy. J Jpn Soc Clin Surg. 1986;47:491–4 (in Japanese).

Yoshioka K. Clinicopathological study of perforated gastric cancer. Kawasaki Med J. 1986;12:152–66 (in Japanese).

Marubayashi S, Oshiro H, Yamamoto Y, Takana I, Nomura S, Kimura A, et al. A study on gastroduodenal perforations. J Hiroshima Med Assoc. 1987;40:1070–4 (in Japanese).

Osawa J, Higashide S, Tamagawa M, Yatagai T, Oguchi M, Shinoda M, et al. Clinical and pathological features of perforated gastric carcinomas. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 1987;20:1676–81 (in Japanese).

Ugai S, Nishijima H, Nishii H, Ogasawara K, Kondoh T, Aoki Y. Five cases of perforated gastric cancer. J Takamatu City Hosp. 1987;3:93–7 (in Japanese).

Mayumi T, Hachisuka K, Yamaguchi A, Isogai M, Ishibashi H, Kato J, et al. A case of early gastric cancer with perforation showing various macroscopic findings. Jpn J Cancer Clin. 1987;33:411–6 (in Japanese).

Hirayama R, Nihei Y, Hamada S, Iishi H, Mishima Y. The surgical therapy for perforated gastric cancer. J Clin Surg. 1987;42:325–9 (in Japanese).

Ishibashi T, Takeyoshi I, Shirakura T. Three cases of perforated gastric cancer: with special reference to perforation of early gastric cancer. Gastroenterol Surg. 1987;10:373–7 (in Japanese).

Sato H, Tanaka T, Yatsuhashi T, Hirokawa A, Yamagata M, Ootsuka Y, et al. A case of perforated gastric cancer combined with leiomyoma. J Nihon Univ Med Assoc. 1988;47:973–6 (in Japanese).

Itoh S, Ohe H, Tokuyama N, Soeda O, Okada D, Lin S, et al. A study of gastric ulcer and cancer perforation. J Jpn Soc Clin Surg. 1988;49:844–7 (in Japanese).

Hiromoto M, Kusakabe T, Tsushima H, Kaetsu T, Maeda T. A case of scirrhous carcinoma of the stomach with perforation. KANTO J Jpn Assoc Acute Med. 1989;10:664–6 (in Japanese).

Nagashima M, Kurihara S, Takaoka A, Kohda H, Kawase H, Satomi A, et al. Two cases of perforated gastric cancer. KANTO J Jpn Assoc Acute Med. 1989;10:668–9 (in Japanese).

Nakazaki T, Hashimoto Y, Ifuku M, Kubota F, Minami H, Takada T, et al. Clinical studies on the cases of perforated gastric cancer. J Jpn Soc Clin Surg. 1989;50:949–53 (in Japanese).

Yara T, Harakuni M, Ajitomi S. A case of perforated gastric carcinoma in Bormann II with 5-year survival after the operation. Okinawa Med J. 1986;26:33–5 (in Japanese).

Kyono S, Onda M, Yoshida M, Yamashita K, Moriyama Y, Tanaka N, et al. Emergency operation for patients with peritonitis due to perforated gastric cancer for recent IZ years. Prog Acute Abdom Med. 1990;10:263–7 (in Japanese).

Anzai H, Yamazaki T, Koyama I, Sukigara M, Omoto R. A study of perforated gastric cancer. Prog Acute Abdom Med. 1990;10:259–62 (in Japanese).

Sekihara T, Nabeya K, Hanaoka T, Fujii M, Koido S. Three cases of perforation in gastric cancer. Prog Acute Abdom Med. 1990;10:169–71 (in Japanese).

Ogino Y, Tomita T, Ishikawa K, Tajima M, Kaneko M, Kadowaki A, et al. A clinical study of emergency operation for the patients with perforation and bleeding of the gastric cancer. Prog Acute Abdom Med. 1991;11:913–5 (in Japanese).

Nakai H, Harafuji I, Orita Y, Shima Y, Watanabe N, Ishii T, et al. A case of perforated gastric cancer which could be diagnosed preoperatively because of intra-abdominal abscess formation. J Hiroshima Med Assoc. 1991;44:1507–9 (in Japanese).

Akiyama N, Kobayashi C, Haga N, Yanagita Y, Kurihara T, Ishizaki M, et al. Clinical study on the five cases of perforated gastric cancer compared with recent 72 case reports in Japan. Kitakanto Med J. 1991;41:345–51 (in Japanese).

Kishikawa H, Nishiwaki N, Ito K, Naruse H, Tanaka H, Honda K. A study of perforated gastric cancer. Proc Nagoya City Hosp. 1991;14:35–8 (in Japanese).

Sasabe H, Onda M, Yamashita K, Moriyama Y, Tanaka N, Egami K, et al. A case of perforated gastric cancer with 90-year-old patient. KANTO J Jpn Assoc Acute Med. 1991;12:434–5 (in Japanese).

Kido K, Kumashiro R, Naitoh H, Yamasaki S, Tanaka K, Ikenaga H, et al. Clinical study of perforated gastric carcinoma. Med Bull Fukuoka Univ. 1991;18:265–70 (in Japanese).

Nishimura H, Hara K, Hikita H, Senga O, Miyagawa M, Tsuchiya S. A case of scirrhous carcinoma of the stomach with perforation. Gastroenterol Surg. 1991;14:1549–53 (in Japanese).

Nakagoe T, Ino M, Hashiguchi K, Tsuchida R, Matsunaga K, Tomita M. Early gastric cancer associated with perforative peritonitis: two case reports and review of literature. Gastroenterol Surg. 1991;14:233–8 (in Japanese).

Mori N, Hachisuka K, Yamaguchi A, Isogai M, Kuze S, Mayumi T, et al. Clinicopathologic studies of perforated gastric cancer. Prog Acute Abdom Med. 1991;11:483–7 (in Japanese).

Kondoh Y, Ogoshi K, Miyaji M, Iwata K, Hara S, Tajima T, et al. The treatment of perforated gastric cancer. Prog Acute Abdom Med. 1991;11:917–20 (in Japanese).

Kishikawa H, Nishiwaki N, Ito K, Naruse H, Tanaka H, Honda K. Perforated gastric cancer associated with the delivery which is misdiagnosed as abruption of placenta. J Jpn Soc Clin Surg. 1992;53:2986–9 (in Japanese).

Mukai M, Kondou Y, Ogoshi K, Noto T, Makuuchi H, Tajima T, et al. A case of perforated early gastric cancer and a review of 45 cases collected from the Japanese literature. J Jpn Soc Clin Surg. 1992;53:1869–73 (in Japanese).

Tanabe H, Watanabe S, Hashimoto T, Imai N, Kano N, Shimokawa K. A case of scirrhous carcinoma of the stomach with perforation. Surgery. 1992;54:1009–11 (in Japanese).

Isozaki H, Okajima K, Yamada S. Gastric cancer with perforative peritonitis. Operation. 1992;46:129–35 (in Japanese).

Kano N, Miyamoto K, Yamada N, Futamura N, Maeda H, Komura Y, et al. Clinical studies on ruptured abdominal organs caused by malignant tumors with emphasis on its treatment and prognosis. Prog Acute Abdom Med. 1992;12:107–10 (in Japanese).

Deguchi H, Ozawa T, Kitahara S, Takatsuka J, Kaneko H, Tsugu Y, Nonaka H. Four cases of perforation with gastric cancer. J Med Soc Toho. 1992;38:845–51 (in Japanese).

Tomoda N, Uchino Y, Ikeda H, Shima H, Hara M, Ohasi M, et al. A study on operated cases of perforated gastric cancer. J Jpn Soc Clin Surg. 1993;54:3071–6 (in Japanese).

Kanamaru T, Saitou Y, Ota K, Hashimoto Y, Matsui S, Fukuda H, et al. Perforated gastric cancer—a clinicopathological study of eight cases. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 1993;26:1261–5 (in Japanese).

Tanabe H, Watanabe S, Hashimoto T, Imai N. Perforated gastric cancer; a report of 5 cases. Jpn J Cancer Clin. 1993;39:663–7 (in Japanese).

Kasakura Y, Murayama I, Yamagata M, Fujii M, Ohtsuki J, Ishii F, et al. A clinicopathological analysis of the cases with perforated gastric cancer. Surgery. 1993;55:561–4 (in Japanese).

Takehana T, Imada T, Abe M, Chen C, Takahashi M, Tokunaga M, et al. Clinical pathology and treatment of perforation in gastric cancer. Jpn J Cancer Clin. 1994;40:1647–52 (in Japanese).

Yasuda H, Yamada N, Onitsuka A. A case of perforated gastric carcinoma which made a cavity between the liver and stomach without signs of peritonitis or abdominal abscess. J Jpn Soc Clin Surg. 1994;55:409–12 (in Japanese).

Kuzu H, Suzuki A, Fuse A, Kameyama J, Tsukamoto M. A case of unique perforation in gastric cancer. J Abdom Emerg Med. 1994;14:935–8 (in Japanese).

Iwai K, Katoh H, Hishiyama H, Ikeda J, Nakamura Y, Shibano N. Perforated gastric cancer. Surgery. 1995;57:983–5 (in Japanese).

Shomura Y, Murabayashi K, Hayashi M, Nakano H, Uehara S, Kusuda T, et al. A resected case of juvenile gastric cancer causing perforation during the course of the observation of pregnancy and an ovarian tumor. J Jpn Soc Clin Surg. 1995;56:741–5 (in Japanese).

Adachi Y, Takahashi I, Okudera Y, Kusaba I, Okita K, Nozue T, et al. Seventy months survival after operation for perforated gastric carcinoma. Surg Ther. 1996;75:613–6 (in Japanese).

Kitakado Y, Tanigawa N, Muraoka R. A case report of perforated early gastric cancer. Arch Jpn Chir. 1997;66:86–90 (in Japanese).

Hasegawa M, Wada N, Naka S, Inoue T, Ishida Y, Sugano I, et al. Clinical study of seven cases of perforated gastric cancer. Jpn J Cancer Clin. 1998;44:1083–8 (in Japanese).

Edazawa H, Yoshida H, Yanou K, Kamada T. Four cases of perforated gastric cancer. J Med Assoc South Hokkaido. 1998;33:245–7 (in Japanese).

Chiba T, Miura K, Sawa N, Okamoto M, Takahashi H, Konno F, et al. A study on the cases with perforation of gastric cancer. Med J Hachinohe City Hosp. 1998;18:97–100 (in Japanese).

Fukuchi M, Takenoshita S, Kojima T, Koitabashi H, Tsukada K. Four cases of perforated gastric cancer. J Abdom Emerg Med. 1998;18:435–8 (in Japanese).

Mori K, Kawahara F, Nakai M, Shima Y, Takeyama S. A case of scirrhous carcinoma of the stomach with perforation. Gastroenterol Endosc. 1999;41:2224–8 (in Japanese).

Numata N, Nagahata Y, Nagata H, Ogino K. Elective radical operation after conservative treatment for gastric perforation in a patient with early gastric cancer. J Jpn Surg Assoc. 1999;60:1000–4 (in Japanese).

Mokuno Y, Chigira H, Katoh T, Yoshida K, Kamiya S, Maeda M. A study on nine cases of perforated gastric cancer. Surgery. 1999;61:561–4 (in Japanese).

Ogawa T, Murabayashi K, Nakano H, Uehara S, Kusuda T, Takahashi K, et al. Report of two cases with perforation of early gastric cancer—a study on 12 perforated cases of gastric cancer including advanced stage. Jpn J Cancer Clin. 1999;45:243–6 (in Japanese).

Funai K, Kanamaru H, Yokoyama H, Shirakawa M, Hashimoto H, Yoshino G. Gastric perforation in early gastric cancer—a case report. J Jpn Surg Assoc. 2000;61:954–7 (in Japanese).

Hanatani Y, Gibo J, Nakatsu M, Toeda H, Ikeda Y, Niimi Y, et al. Diagnosis and surgical treatment of 8 patients with perforated gastric cancer. J Abdom Emerg Med. 2000;20:1023–8 (in Japanese).

Oshita H, Tanemura H, Kanno A, Kusakabe M, Tonomura S, Hosono Y, et al. Evaluation of eight cases of perforated gastric carcinoma. Surgery. 2001;63:602–5 (in Japanese).

Hashimoto M, Akita Y, Kitagawa Y, Ito N, Sasaki E, Akutagawa A, et al. A case of rupture and double perforations of gastric cancer. J Jpn Surg Assoc. 2001;62:670–3 (in Japanese).

Ugajin W, Masuda H, Nakayama H, Aoki N, Koide H, Nakamura Y, et al. A study of perforation of gastric cancer. J Nippon Med Sch. 2001;60:24–8 (in Japanese).

Yabusaki H, Nashimoto A. Perforated gastric cancer. Operation. 2002;56:1917–24 (in Japanese).

Yoshizaki K, Nagashima T, Mizukami Y, Ikuta K, Hiramatsu K, Hasegawa M. A case report of perforation of early gastric cancer. Surgery. 2003;65:1721–4 (in Japanese).

Kuratate S, Yogita S, Yada S, Miyauchi T, Kaneda Y, Yamaguchi T. A case of 6-year postoperative survival after perforated advanced gastric cancer. J Clin Surg. 2003;58:1565–8 (in Japanese).

Hiromatsu T, Kobayashi K, Ota S. Four cases of perforated gastric cancer. J Abdom Emerg Med. 2003;23:805–9 (in Japanese).

Murakami N, Kitagawa S, Adachi I, Morita K, Iino K, Yamada T. A case of scirrhous carcinoma with perforation enforced curative operation. J Clin Surg. 2003;58:1125–8 (in Japanese).

Sato T, Yamaguchi T, Ohta K, Ohyama S, Ueno M, Nagano H, et al. A successfully saved case of stage IV gastric cancer with perforation due to effectiveness of neutrophil elastase inhibitor. Prog Med. 2003;23:457–8 (in Japanese).

Taniguchi K, Suenaga H, Kiriyama K, Wada M, Hirai A. A case report of calcified gastric cancer presented with perforation. J Jpn Surg Assoc. 2003;64:1900–2 (in Japanese).

Yagihashi N, Ito H, Osawa T, Taniguchi S. Report of four cases of perforated gastric cancer. Med J Kuroishi City Hosp. 2004;10:15–8 (in Japanese).

Matsuyama R, Sato Y, Misuta K, Hasegawa S, Hasegawa S, Mori R, et al. A case of Borrmann type 4 cancer of the stomach with perforation. J Abdom Emerg Med. 2004;24:927–31 (in Japanese).

Okinaga K, Shiratori M, Fukushima R, Inaba T. Treatment for perforated gastric cancer. Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;19:953–8 (in Japanese).

Ninomiya S, Yoshida T, Morii Y, Matsuyama T. A case of elective gastrectomy and lymph node dissection for perforated gastric cancer. Surgery. 2004;66:461–3 (in Japanese).

Fukuda N, Wada J, Takahashi S, Takahashi K, Miura Y. Perforated gastric carcinoma treated with laparoscopic omental patch repair followed by open radical surgery—report of a case. J Jpn Surg Assoc. 2005;66:2431–5 (in Japanese).

Kawase H, Ebihara Y, Kitashiro S, Okushiba S, Kato H, Kondo S. A case of gastric perforation of early gastric cancer treated by two-step radical surgery after laparoscopic omentopexy. J Jpn Surg Assoc. 2005;66:2426–30 (in Japanese).

Urahashi T, Miura O, Kawano T, Toda T, Minamisono Y, Nagasaki S. A case of perforated superficial wide-spreading early gastric cancer with localized subphrenic abscess. Surgery. 2005;67:974–7 (in Japanese).

Kasama K, Kumamoto Y, Katayama K. Two cases of perforated gastric cancer which could be performed emergency operation after the diagnosis as perforative peritonitis at emergency department. KANTO J Jpn Assoc Acute Med. 2006;27:40–1 (in Japanese).

Uemura S. Perforative early gastric cancer: a case report and review of the literature. J Abdom Emerg Med. 2006;26:859–62 (in Japanese).

Tajima Y, Gonda T, Nagamine T, Yoshida H, Suto K, Ishida H. A case of gallbladder cancer with porcelain gallbladder which could be diagnosed after the perforation of gastric cancer. J Saitama M S. 2006;41:22–6 (in Japanese).

Yagi Y, Kawai J, Takahashi K, Ichikawa K. A case of perforated gastric cancer treated by two-staged curative resection after laparoscopic omentopexy. Surgery. 2006;68:1089–92 (in Japanese).

Waku T. Clinical review of four cases of perforative gastric cancer. J Abdom Emerg Med. 2006;26:73–6 (in Japanese).

Kunieda K, Yahata K, Ota H, Ito M, Fukui T, Nagao I, et al. Study of cases of perforated gastric cancer. Ann Gifu Pref Gen Med Center. 2006;27:21–4 (in Japanese).

Hirakawa K, Teramoto M, Iguchi C, Saito A, Kawabata K. A case of gastric carcinoma who present with acute abdomen due to the perforation of stomach. J Otokuni Med Assoc. 2006;15:43–5 (in Japanese).

Kato T, Takaya K, Suzuki R, Sawada M, Kitamura M. Perforated gastric carcinoma: a case report and literature review. J Abdom Emerg Med. 2007;27:613–6 (in Japanese).

Hayashi N, Hasuike Y, Fujiwara S, Fukuchi N, Tujie M, Yoshida T. A case of perforated gastric cancer treated with an emergency laparoscopic occlusion followed by radical resection. J Jpn Soc Endosc Surg. 2007;12:61–5 (in Japanese).

Fujita T, Takano M, Matsuyama H, Suzuki T, Hatanaka M, Endo T, et al. A case of gastric cancer perforation during chemotherapy with TS-1. Jpn J Cancer Clin. 2007;53:457–62 (in Japanese).

Ando H, Maeda S, Kameoka N, Tsuboi S. A case of perforated gastric cancer associated with pregnancy that was recognized at caesarean operation. J Abdom Emerg Med. 2007;27:777–9 (in Japanese).

Yonezawa K, Shimomatsuya T. Perforated early gastric cancer in 89-year-old patient. J Abdom Emerg Med. 2007;27:963–7 (in Japanese).

Sakai T, Yamada Y. A successfully treated case of type 4 cancer of the stomach with perforation and invasion to the transverse colon by primary resection of the stomach and the transverse colon. J Jpn Surg Assoc. 2008;69:360–4 (in Japanese).

Ito M, Tanakaya K, Takeuchi H, Kanazawa T. A case of perforated gastric carcinoma with was false negative by intraoperative histopathologic diagnosis. J Jpn Coll Surg. 2008;33:752–5 (in Japanese).

Watanabe K, Kato T, Suzuki M, Shibata Y, Yoshihara M, Nagasawa K, et al. A strategy of treatment for perforated gastric cancer. J Jpn Surg Assoc. 2009;70:6–11 (in Japanese).

Yanagisawa S, Tsuchiya S, Kaiho T, Togawa A, Shinmura K, Okamoto R. An analysis of patients with perforated gastric cancer. J Jpn Surg Assoc. 2009;70:1271–5 (in Japanese).

Yamaguchi R, Inagawa S, Terashima H, Ishikawa A, Sasaki R, Ohkohchi N. A case of long-term survival after resection of a perforated gastric cancer with liver metastasis. J Jpn Surg Assoc. 2009;70:1376–82 (in Japanese).

Udaka T, Kobayashi N, Kudo M, Mizuta M, Shirakawa K. Clinical review of perforated gastric cancer. J Abdom Emerg Med. 2009;29:437–40 (in Japanese).

Moriwaki Y, Toyoda H, Kosuge T, Sugiyama M. A senile case with gastric cancer perforation saved by emergency palliative resection who lived for 14 months after the surgery. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 2009;42:25–30 (in Japanese).

Japanese Gastric Cancer A. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma. 2nd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10–24.

Jwo SC, Chien RN, Chao TC, Chen HY, Lin CY. Clinicopathological features, surgical management, and disease outcome of perforated gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2005;91:219–25.

Kasakura Y, Ajani JA, Fujii M, Mochizuki F, Takayama T. Management of perforated gastric carcinoma: a report of 16 cases and review of world literature. Am Surg. 2002;68:434–40.

Shih CH, Yu MC, Chao TC, Huang TL, Jan YY, Chen MF. Outcome of perforated gastric cancer: twenty years experience of one institute. Hepatogastroenterology. 2010;57:1320–4.

Kasakura Y, Ajani JA, Mochizuki F, Morishita Y, Fujii M, Takayama T. Outcomes after emergency surgery for gastric perforation or severe bleeding in patients with gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2002;80:181–5.

Lunevicius R, Morkevicius M. Systematic review comparing laparoscopic and open repair for perforated peptic ulcer. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1195–207.

Bertleff MJ, Halm JA, Bemelman WA, van der Ham AC, van der Harst E, Oei HI, et al. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open repair of the perforated peptic ulcer: the LAMA Trial. World J Surg. 2009;33:1368–73.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Manabu Ohashi (Department of Gastroenterological Surgery, Cancer Institute Hospital) and Yoshiaki Iwasaki (Department of Surgery, Tokyo Metropolitan Cancer and Infectious Diseases Center Komagome Hospital) for insightful comments and suggestions regarding the conduct of this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hata, T., Sakata, N., Kudoh, K. et al. The best surgical approach for perforated gastric cancer: one-stage vs. two-stage gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer 17, 578–587 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-013-0308-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-013-0308-0