Abstract

We consider the problem of computing the minimum value \(f_{\min ,K}\) of a polynomial f over a compact set \(K\subseteq {\mathbb {R}}^n\), which can be reformulated as finding a probability measure \(\nu \) on \(K\) minimizing \(\int _Kf d\nu \). Lasserre showed that it suffices to consider such measures of the form \(\nu = q\mu \), where q is a sum-of-squares polynomial and \(\mu \) is a given Borel measure supported on \(K\). By bounding the degree of q by 2r one gets a converging hierarchy of upper bounds \(f^{(r)}\) for \(f_{\min ,K}\). When K is the hypercube \([-1, 1]^n\), equipped with the Chebyshev measure, the parameters \(f^{(r)}\) are known to converge to \(f_{\min , K}\) at a rate in \(O(1/r^2)\). We extend this error estimate to a wider class of convex bodies, while also allowing for a broader class of reference measures, including the Lebesgue measure. Our analysis applies to simplices, balls and convex bodies that locally look like a ball. In addition, we show an error estimate in \(O(\log r / r)\) when \(K\) satisfies a minor geometrical condition, and in \(O(\log ^2 r / r^2)\) when \(K\) is a convex body, equipped with the Lebesgue measure. This improves upon the currently best known error estimates in \(O(1 / \sqrt{r})\) and \(O(1/r)\) for these two respective cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

1.1 Lasserre’s measure-based hierarchy

Let \(K\subseteq {\mathbb {R}}^n\) be a compact set and let \(f\in {\mathbb {R}}[x]\) be a polynomial. We consider the minimization problem

Computing \(f_{\min , K}\) is a hard problem in general, and some well-known problems from combinatorial optimization are among its special cases. For example, it is shown in [13, 24] that the stability number \(\alpha (G)\) of a graph \(G = ([n], E)\) is given by

where we take \(K= \{x \in {\mathbb {R}}^n : x \ge 0, \ \sum _{i=1}^n x_i = 1\}\) to be the standard simplex in \({\mathbb {R}}^n\).

Problem (1) may be reformulated as the problem of finding a probability measure \(\nu \) on \(K\) for which the integral \(\int _Kfd\nu \) is minimized. Indeed, for any such \(\nu \) we have \(\int _Kf d\nu \ge f_{\min , K}\int _Kd \nu = f_{\min , K}\). On the other hand, if \(a \in K\) is a global minimizer of \(f\) in K, then we have \(\int _Kfd\delta _a = f(a) = f_{\min , K}\), where \(\delta _a\) is the Dirac measure centered at a.

Lasserre [21] showed that it suffices to consider measures of the form \(\nu = q\mu \), where \(q\in \Sigma \) is a sum-of-squares polynomial and \(\mu \) is a (fixed) reference Borel measure supported by \(K\). That is, we may reformulate (1) as

For each \(r \in {\mathbb {N}}\) we may then obtain an upper bound \(f^{(r)}_{K, \mu }\) for \(f_{\min , K}\) by limiting our choice of \(q\) in (2) to polynomials of degree at most 2r:

Here, \(\Sigma _r\) denotes the set of all sum-of-squares polynomials of degree at most 2r. We shall also write \(f^{(r)} = f^{(r)}_{K, \mu }\) for simplicity. As detecting sum-of-squares polynomials is possible using semidefinite programming, the program (3) can be modeled as an SDP [21]. Moreover, the special structure of this SDP allows a reformulation to an eigenvalue minimization problem [21], as will be briefly described below.

By definition, we have \(f_{\min , K}\le f^{(r+1)} \le f^{(r)}\) for all \(r \in {\mathbb {N}}\) and

In this paper we are interested in upper bounding the convergence rate of the sequence \((f^{(r)})_r\) to \(f_{\min , K}\) in terms of r. That is, we wish to find bounds in terms of r for the parameter:

often also denoted \(E^{({r})}_{{}}({f})\) for simplicity when there is no ambiguity on \(K,\mu \).

1.2 Related work

Bounds on the parameter \(E^{({r})}_{{K,\mu }}({f})\) have been shown in the literature for several different sets of assumptions on \(K, \mu \) and \(f\). Depending on these assumptions, two main strategies have been employed, which we now briefly discuss.

Algebraic analysis via an eigenvalue reformulation The first strategy relies on a reformulation of the optimization problem (3) as an eigenvalue minimization problem (see [12, 21]). We describe it briefly, in the univariate case \(n=1\) only, for simplicity and since this is the case we need. Let \(\{ p_r \in {\mathbb {R}}[x]_r: r \in {\mathbb {N}}\}\) be the (unique) orthonormal basis of \({\mathbb {R}}[x]\) w.r.t. the inner product \(\langle p_i, p_j \rangle = \int _Kp_i p_j d\mu \). For each \(r \in {\mathbb {N}}\), we then define the (generalized) truncated moment matrix \(M_{r,f}\) of \(f\) by setting

It can be shown that \(f^{(r)} =\lambda _{\min }(M_{r,f})\), the smallest eigenvalue of the matrix \(M_{r,f}\). Any bounds on the eigenvalues of \(M_{r,f}\) thus immediately translate to bounds on \(f^{(r)}\).

In [10], the authors determine the exact asymptotic behaviour of \(\lambda _{\min }(M_{r,f})\) in the case that \(f\) is a quadratic polynomial, \(K= [-1, 1]\) and \(d\mu (x) = (1-x^2)^{-\frac{1}{2}}dx\), known as the Chebyshev measure. Based on this, they show that \(E^{({r})}_{{}}({f})=O(1/r^2)\) and extend this result to arbitrary multivariate polynomials \(f\) on the hypercube \([-1, 1]^n\) equipped with the product measure \(d\mu (x) = \prod _i^n (1-x_i)^{-1/2}dx_i\). In addition, they prove that \(E^{({r})}_{{}}({f}) = \Theta (1/r^2)\) for linear polynomials, which thus shows that in some sense quadratic convergence is the best we can hope for. (This latter result is shown in [10] for all measures with Jacobi weight on \([-1,1]\)).

The orthogonal polynomials corresponding to the measure \((1-x^2)^{-1/2}dx\) on \([-1,1]\) are the Chebyshev polynomials of the first kind, denoted by \(T_{r}\). They are well-studied objects (see, e.g., [25]). In particular, they satisfy the following three-term recurrence relation

This imposes a large amount of structure on the matrix \(M_{r, f}\) when \(f\) is quadratic, which has been exploited in [10] to obtain information on its smallest eigenvalue.

The main disadvantage of the eigenvalue strategy is that it requires the moment matrix of \(f\) to have a closed form expression which is sufficiently structured so as to allow for an analysis of its eigenvalues. Closed form expressions for the entries of the matrix \(M_{r,f}\) are known only for special sets \(K\), such as the interval \([-1,1]\), the unit ball, the unit sphere, or the simplex, and only with respect to certain measures.

However, as we will see in this paper, the convergence analysis from [10] in \(O(1/r^2)\) for the interval \([-1,1]\) equipped with the Chebyshev measure, can be transported to a large class of compact sets, such as the interval \([-1,1]\) with more general measures, the ball, the simplex, and ‘ball-like’ convex bodies.

Analysis via the construction of feasible solutions A second strategy to bound the convergence rate of the parameters \(E^{({r})}_{{}}({f})\) is to construct explicit sum-of-squares density functions \(q_{r} \in \Sigma _r\) for which the integral \(\int _Kq_r fd\mu \) is close to \(f_{\min , K}\). In contrast to the previous strategy, such constructions will only yield upper bounds on \(E^{({r})}_{{}}({f})\).

As noted earlier, the integral \(\int _Kfd\nu \) may be minimized by selecting the probability measure \(\nu = \delta _a\), the Dirac measure at a global minimizer a of \(f\) on \(K\). When the reference measure \(\mu \) is the Lebesgue measure, it thus intuitively seems sensible to consider sum-of-squares densities \(q_{r}\) that approximate the Dirac delta in some way.

This approach is followed in [12]. There, the authors consider truncated Taylor expansions of the Gaussian function \(e^{-t^2/2\sigma }\), which they use to define the sum-of-squares polynomials

Setting \(q_r(x) \sim \phi _{r}(||x-a||)\) for carefully selected standard deviation \(\sigma = \sigma (r)\), they show that \(\int _{K} f(x) q_{r}(x) dx - f(a) = O(1/\sqrt{r})\) when \(K\) satisfies a minor geometrical assumption (Assumption 1 below), which holds, e.g., if \(K\) is a convex body or if it is star-shaped with respect to a ball.

In subsequent work [8], the authors show that if \(K\) is assumed to be a convex body, then a bound in \(O(1/r)\) may be obtained by setting \(q_{r} \sim \phi _r(f(x))\). As explained in [8], the sum-of-squares density \(q_r\) in this case can be seen as an approximation of the Boltzman density function for \(f\), which plays an important role in simulated annealing.

The advantage of this second strategy seems to be its applicability to a broad class of sets \(K\) with respect to the natural Lebesgue measure. This generality, however, is so-far offset by significantly weaker bounds on \(E^{({r})}_{{}}({f})\). Another main contribution of this paper will be to show improved bounds on \(E^{({r})}_{{}}({f})\) for this broad class of sets K.

Analysis for the hypersphere Tight results are known for polynomial minimization on the unit sphere \(S^{n-1}=\{x\in {\mathbb {R}}^n: \sum _ix_i^2=1\}\), equipped with the Haar surface measure. Doherty and Wehner [15] have shown a convergence rate in \(O(1/r)\), by using harmonic analysis on the sphere and connections to quantum information theory. In the very recent work [11], the authors show an improved convergence rate in \(O(1/r^2)\), by using a reduction to the case of the interval \( [-1,1]\) and the above mentioned convergence rate in \(O(1/r^2)\) for this case. This reduction is based on replacing f by an easy (linear) upper estimator. This idea was already exploited in [8, 12] (where a quadratic upper estimator was used) and we will also exploit it in this paper.

1.3 Our contribution

The contribution of this paper is showing improved bounds on the convergence rate of the parameters \(E^{({r})}_{{K,\mu }}({f})\) for a wide class of sets K and measures \(\mu \). It is twofold.

Firstly, we extend the known bound from [10] in \(O(1/r^2)\) for the hypercube \([-1,1]^n\) equipped with the Chebyshev measure, to a wider class of convex bodies. Our results hold for the ball \({B^n}\), the simplex \(\Delta ^{n}\), and ‘ball-like’ convex bodies (see Definition 3) equipped with the Lebesgue measure. For the ball and hypercube, they further hold for a wider class of measures; namely for the measures given by

on the ball, and the measures

on the hypercube. Note that for the hypercube, setting \(\lambda = -\frac{1}{2}\) yields the Chebyshev measure, and that for both the ball and the hypercube, setting \(\lambda = 0\) yields the Lebesgue measure. The rate \(O(1/r^2)\) also holds for any compact K equipped with the Lebesgue measure under the assumption of existence of a global minimizer in the interior of K. These results are presented in Sect. 3.

Secondly, we improve the known bounds in \(O(1/\sqrt{r})\) and \(O(1/r)\) for general compact sets (under Assumption 1) and convex bodies equipped with the Lebesgue measure, established in [8, 12], respectively. For general compact sets, we prove a bound in \(O(\log r / r)\), and for convex bodies we show a bound in \(O(\log ^2 r / r^2)\). These results are exposed in Sect. 4.

For our results in Sect. 3, we will use several tools that will enable us to reduce to the case of the interval \([-1,1]\) equipped with the Chebyshev measure. These tools are presented in Sects. 2 and 3. They include: (a) replacing K by an affine linear image of it (Sect. 2.3); (b) replacing f by an upper estimator (easier to analyze, obtained via Taylor’s theorem) (Sect. 2.4); (c) transporting results between two comparable weight functions on K and between two convex sets \(K,{{\widehat{K}}}\) which look locally the same in the neighbourhood of a global minimizer (Sects. 3.1, 3.2). In particular, the result of Proposition 1 will play a key role in our treatment.

To establish our results in Sect. 4 we will follow the second strategy sketched above, namely we will define suitable sum-of-squares polynomials that approximate well the Dirac delta at a global minimizer. However, instead of using truncations of the Taylor expansion of the Gaussian function or of the Boltzman distribution as was done in [8, 12], we will now use the so-called needle polynomials from [19] (constructed from the Chebyshev polynomials, see Sect. 4.1). In Table 1 we provide an overview of both known and new results.

Finally, we illustrate some of the results in Sects. 3 and 4 with numerical examples in Sect. 5.

2 Preliminaries

In this section, we first introduce some notation that we will use throughout the rest of the paper and recall some basic terminology and results about convex bodies. We then show that the error \(E^{({r})}_{{}}({f})\) is invariant under nonsingular affine transformations of \({\mathbb {R}}^n\). Finally, we introduce the notion of upper estimators for \(f\). Roughly speaking, this tool will allow us to replace \(f\) in the analysis of \(E^{({r})}_{{}}({f})\) by a simpler function (usually a quadratic, separable polynomial). We will make use of this extensively in both Sects. 3 and 4.

2.1 Notation

For \(x, y \in {\mathbb {R}}^n\), \(\langle x, y \rangle \) denotes the standard inner product and \(\Vert x\Vert ^2 = \langle x, x \rangle \) the corresponding norm. We write \(B^n_{\rho }(c) := \{x \in {\mathbb {R}}^n : \Vert x - c\Vert \le \rho \}\) for the n-dimensional ball of radius \(\rho \) centered at c. When \(\rho = 1\) and \(c = 0\), we also write \({B^n}:= B^n_{1}(0)\).

Throughout, \(K\subseteq {\mathbb {R}}^n\) is always a compact set with non-empty interior, and \(f\) is an n-variate polynomial. We let \(\nabla f(x)\) (resp., \(\nabla ^2f(x)\)) denote the gradient (resp., the Hessian) of \(f\) at \(x \in {\mathbb {R}}^n\), and introduce the parameters

Whenever we write an expression of the form

we mean that there exists a constant \(c > 0\) such that \(E^{({r})}_{{}}({f})\le c/r^2\) for all \(r \in {\mathbb {N}}\), where c depends only on \(K, \mu \), and the parameters \(\beta _{{f}, {K}}, \gamma _{{f}, {K}}\). Some of our results are obtained by embedding \(K\) into a larger set \({\widehat{K}}\subseteq {\mathbb {R}}^n\). If this is the case, then c may depend on \(\beta _{{f}, {{\widehat{K}}}}, \gamma _{{f}, {{\widehat{K}}}}\) as well. If there is an additional dependence of c on the global minimizer a of \(f\) on \(K\), we will make this explicit by using the notation “\(O_a\)”.

2.2 Convex bodies

Let \(K\subseteq {\mathbb {R}}^n\) be a convex body, i.e., a compact, convex set with non-empty interior. We say \(v \in {\mathbb {R}}^n\) is an (inward) normal of \(K\) at \(a \in K\) if \(\langle v, x-a \rangle \ge 0\) holds for all \(x \in K\). We refer to the set of all normals of \(K\) at a as the normal cone, and write

We will make use of the following basic result.

Lemma 1

(e.g., [2, Prop. 2.1.1]) Let \(K\) be a convex body and let \(g : {\mathbb {R}}^n \rightarrow {\mathbb {R}}\) be a continuously differentiable function with local minimizer \(a \in K\). Then \(\nabla g (a) \in N_{K}(a)\).

Proof

Suppose not. Then, by definition of \(N_{K}(a)\), there exists an element \(y \in K\) such that \(\langle \nabla g(a), y - a \rangle < 0\). Expanding the definition of the gradient this means that

which implies \(g(ty + (1-t) a) < g(a)\) for all \(t > 0\) small enough. But \(ty + (1-t) a \in K\) by convexity, contradicting the fact that a is a local minimizer of g on \(K\). \(\square \)

The set \(K\) is smooth if it has a unique unit normal \(v(a)\) at each boundary point \(a \in \partial K\). In this case, we denote by \(T_aK\) the (unique) hyperplane tangent to \(K\) at a, defined by the equation \(\langle x-a, v(a) \rangle = 0\).

For \(k \ge 1\), we say \(K\) is of class \(C^k\) if there exists a convex function \(\Psi \in C^k({\mathbb {R}}^n, {\mathbb {R}})\) such that \(K= \{ x \in {\mathbb {R}}^n : \Psi (x) \le 0\}\) and \(\partial K= \{x \in {\mathbb {R}}^n : \Psi (x) = 0\}\). If \(K\) is of class \(C^k\) for some \(k \ge 1\), it is automatically smooth in the above sense.

We refer, e.g., to [1] for a general reference on convex bodies.

2.3 Linear transformations

Suppose that \(\phi : {\mathbb {R}}^n \rightarrow {\mathbb {R}}^n\) is a nonsingular affine transformation, given by \(\phi (x) = Ux + c\). If \(q\) is a sum-of-squares density function w.r.t. the Lebesgue measure on \(\phi (K)\), then we have

As a result, the polynomial \({{\widehat{q}}} := (q\circ \phi ) / \int _Kq(\phi (x))dx = (q\circ \phi ) \cdot |\det U|\) is a sum of squares density function w.r.t. the Lebesgue measure on \(K\). It has the same degree as q, and it satisfies

We have just shown the following.

Lemma 2

Let \(\phi : {\mathbb {R}}^n \rightarrow {\mathbb {R}}^n\) be a non-singular affine transformation. Write \(g := f\circ \phi ^{-1}\). Then we have

2.4 Upper estimators

Given a point \(a \in K\) and two functions \(f,g : K\rightarrow {\mathbb {R}}\), we write \(f\le _a g\) if \(f(a) = g(a)\) and \(f(x) \le g(x)\) for all \(x \in K\); we then say that g is an upper estimator for \(f\) on \(K\), which is exact at a. The next lemma, whose easy proof is omitted, will be very useful.

Lemma 3

Let \(g : K\rightarrow {\mathbb {R}}\) be an upper estimator for \(f\), exact at one of its global minimizers on \(K\). Then we have \(E^{({r})}_{{}}({f}) \le E^{({r})}_{{}}({g})\) for all \(r \in {\mathbb {N}}\).

Remark 1

We make the following observations for future reference.

-

1.

Lemma 3 tells us that we may always replace \(f\) in our analysis by an upper estimator which is exact at one of its global minimizers. This is useful if we can find an upper estimator that is significantly simpler to analyze.

-

2.

We may always assume that \(f_{\min , K}= 0\), in which case \(f(x) \ge 0\) for all \(x\in K\) and \(E^{({r})}_{{}}({f}) = f^{(r)}\). Indeed, if we consider the function g given by \(g(x) = f(x) - f_{\min , K}\), then \(g_{\min , K} = 0\), and for every density function q on \(K\), we have

$$\begin{aligned} \int _Kg(x)q(x)d\mu (x) = \int _Kf(x)q(x)d\mu (x) - f_{\min , K}, \end{aligned}$$showing that \(E^{({r})}_{{}}({f}) = E^{({r})}_{{}}({g}) = g^{(r)}\) for all \(r \in {\mathbb {N}}\).

In the remainder of this section, we derive some general upper estimators based on the following variant of Taylor’s theorem for multivariate functions.

Theorem 1

(Taylor’s theorem) For \(f \in C^2({\mathbb {R}}^n, {\mathbb {R}})\) and \(a \in K\) we have

where \(\gamma _{K,f}\) is the constant from (5).

Lemma 4

Let \(a \in K\) be a global minimizer of \(f\) on \(K\). Then \(f\) has an upper estimator g on \(K\) which is exact at a and satisfies the following properties:

-

(i)

g is a quadratic, separable polynomial.

-

(ii)

\(g(x) \ge f(a) + \gamma _{{K}, {f}} \Vert x-a\Vert ^2\) for all \(x \in K\).

-

(iii)

If \(a \in {{\,\mathrm{int}\,}}{K}\), then \(g(x) \le f(a) + \gamma _{{K}, {f}} \Vert x-a\Vert ^2\) for all \(x \in K\).

Proof

Consider the function g defined by

which is an upper estimator of \(f\) exact at a by Theorem 1. As we have \(\Vert x-a\Vert ^2 = \sum _{i}^n (x_i - a_i)^2\), g is indeed a quadratic, separable polynomial.

As a is a global minimizer of \(f\) on \(K\), we know by Lemma 1 that \(\nabla f(a) \in N_{K}(a)\). This means that \(\langle \nabla f(a), x-a \rangle \ge 0\) for all \(x \in K\), which proves the second property.

If \(a \in {{\,\mathrm{int}\,}}{K}\), we must have \(\nabla f(a) = 0\), and the third property follows. \(\square \)

In the special case that \(K\) is a ball and \(f\) has a global minimizer a on the boundary of \(K\), we have an upper estimator for \(f\), exact at a, which is a linear polynomial.

Lemma 5

Assume that \(f(a) = f_{\min , B^n_{\rho }(c)}\) for some \(a \in \partial B^n_{\rho }(c)\). Then there exists a linear polynomial g with \(f\le _a g\) on \(B^n_{\rho }(c)\).

Proof

Write \(K=B^n_{\rho }(c)\) and \(\gamma =\gamma _{K,f}\) for simplicity. In view of Lemma 4, we have \(f(x)\le g(x)\) for all \(x\in K\), where g is the quadratic polynomial from relation (6). Since \(a\in \partial K\) is a global minimizer of \(f\) on K, we have \(\nabla f(a) \in N_{K}(a)\) by Lemma 1, and thus \(\nabla f(a) = \lambda (c-a)\) for some \(\lambda \ge 0\). Therefore we have

On the other hand, for any \(x\in K\) we have

Combining these facts we get

So h(x) is a linear upper estimator of f with \(h(a)=f(a)\), as desired. \(\square \)

Remark 2

As can be seen from the above proof, the assumption in Lemma 5 that \(a \in \partial K= \partial B^n_{\rho }(c)\) is a global minimizer of \(f\) on \(K\) may be replaced by the weaker assumption that \(\nabla f(a) \in N_{K}(a)\).

Finally, we give a very simple upper estimator, which will be used in Sect. 4.

Lemma 6

Recall the constant \(\beta _{{K}, {f}}\) from (5). Let a be a global minimizer of \(f\) on \(K\). Then we have

3 Special convex bodies

In this section we extend the bound \(O(1/r^2)\) from [10] on \(E^{({r})}_{{K, \mu }}({f})\), when \(K= [-1, 1]^n\) is equipped with the Chebyshev measure \(d\mu (x) = \prod _{i=1}^n (1-x_i^2)^{-\frac{1}{2}}dx_i\), to a broader class of convex bodies \(K\) and reference measures \(\mu \).

First, we show that, for the hypercube \(K=[-1,1]^n\), we still have \(E^{({r})}_{{K, \mu }}({f}) = O(1/r^2)\) for all polynomial f and all measures of the form \(d\mu (x) = \prod _{i=1}^n (1-x_i^2)^{\lambda }dx_i\) with \(\lambda > -1/2\). Previously this was only known to be the case when \(f\) is a linear polynomial. Note that, for \(\lambda = 0\), we obtain the Lebesgue measure on \([-1, 1]^n\). Next, we use this result to show that \(E^{({r})}_{{{B^n}, \mu }}({f}) = O(1/r^2)\) for all measures \(\mu \) on the unit ball \({B^n}\) of the form \(d\mu (x) = (1-||x||^2)^{\lambda }dx\) with \(\lambda \ge 0\). We apply this result to also obtain \(E^{({r})}_{{K, \mu }}({f}) = O(1/r^2)\) when \(\mu \) is the Lebesgue measure and \(K\) is a ‘ball-like’ convex body, meaning it has inscribed and circumscribed tangent balls at all boundary points (see Definition 3 below). The primary new tool we use to obtain these results is Proposition 1, which tells us that the behaviour of \(E^{({r})}_{{K, \mu }}({f})\) essentially only depends on the local behaviour of \(f\) and \(\mu \) in a neighbourhood of a global minimizer a of \(f\) on \(K\).

3.1 Measures and weight functions

A function \(w_{} : {{\,\mathrm{int}\,}}{K} \rightarrow {\mathbb {R}}_{> 0}\) is a weight function on \(K\) if it is continuous and satisfies \(0< \int _Kw_{}(x) dx < \infty \). A weight function \(w_{}\) gives rise to a measure \(\mu _{w_{}}\) on \(K\) defined by \(d\mu _{w_{}}(x) := w_{}(x)dx\). We note that if \(K\subseteq {\widehat{K}}\), and \(\widehat{w_{}}\) is a weight function on \({\widehat{K}}\), it can naturally be interpreted as a weight function on \(K\) as well, by simply restricting its domain (assuming \(\int _K\widehat{w_{}}(x) dx > 0\)). In what follows we will implicitly make use of this fact.

Definition 1

Given two weight functions \(w_{}, \widehat{w_{}}\) on \(K\) and a point \(a \in K\), we say that \(\widehat{w_{}} \preceq _{a} w_{}\) on \(K\) if there exist constants \(\epsilon , m_{a} > 0\) such that

If the constant \(m_{a}\) can be chosen uniformly, i.e., if there exists a constant \(m > 0\) such that

then we say that \(\widehat{w_{}} \preceq _{} w_{}\) on \(K\).

Remark 3

We note the following facts for future reference:

-

(i)

As weight functions are continuous on the interior of \(K\) by definition, we always have \(\widehat{w_{}} \preceq _{a} w_{}\) if \(a \in {{\,\mathrm{int}\,}}{K}\).

-

(ii)

If \(w_{}\) is bounded from below, and \(\widehat{w_{}}\) is bounded from above on \({{\,\mathrm{int}\,}}{K}\), then we automatically have \(\widehat{w_{}} \preceq _{} w_{}\).

3.2 Local similarity

Assuming that the global minimizer a of \(f\) on \(K\) is unique, sum-of-squares density functions \(q\) for which the integral \(\int _{K} q(x) f(x) d \mu (x)\) is small should in some sense approximate the Dirac delta function centered at a. With this in mind, it seems reasonable to expect that the quality of the bound \(f^{(r)}\) depends in essence only on the local properties of \(K\) and \(\mu \) around a. We formalize this intuition here.

Definition 2

Suppose \(K\subseteq {\widehat{K}}\subseteq {\mathbb {R}}^n\). Given \(a \in K\), we say that \(K\) and \({\widehat{K}}\) are locally similar at a, which we denote by \(K\subseteq _a {\widehat{K}}\), if there exists \(\epsilon > 0\) such that

Clearly, \(K\subseteq _a {\widehat{K}}\) for any point \(a\in {{\,\mathrm{int}\,}}{K}\).

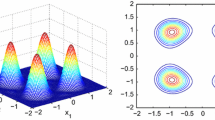

Figure 1 depicts some examples of locally similar sets.

Proposition 1

Let \(K\subseteq {\widehat{K}}\subseteq {\mathbb {R}}^n\), let \(a \in K\) be a global minimizer of \(f\) on \(K\) and assume \(K\subseteq _a {\widehat{K}}\). Let \(w_{}, \widehat{w_{}}\) be two weight functions on \(K, {\widehat{K}}\), respectively. Assume that \(\widehat{w_{}}(x) \ge w_{}(x)\) for all \(x \in {{\,\mathrm{int}\,}}{K}\), and that \(\widehat{w_{}} \preceq _{a} w_{}\). Then there exists an upper estimator g of \(f\) on \({\widehat{K}}\) which is exact at a and satisfies

for all \(r \in {\mathbb {N}}\) large enough. Here \(m_a > 0\) is the constant defined by (7).

Recall that if g is an upper estimator for \(f\) which is exact at one of its global minimizers, we then have \(E^{({r})}_{{K, w_{}}}({f}) \le E^{({r})}_{{K, w_{}}}({g})\) by Lemma 3. Proposition 1 then allows us to bound \(E^{({r})}_{{K, w_{}}}({f})\) in terms of \(E^{({r})}_{{{\widehat{K}}, \widehat{w_{}}}}({g})\). For its proof, we first need the following lemma.

Lemma 7

Let \(a \in K\), and assume that \(K\subseteq _a {\widehat{K}}\). Then any normal vector of \(K\) at a is also a normal vector of \({\widehat{K}}\). That is, \(N_{K}(a) \subseteq N_{{\widehat{K}}}(a).\)

Proof

Let \(v \in N_{K}(a)\). Suppose for contradiction that \(v \not \in N_{{\widehat{K}}}(a)\). Then, by definition of the normal cone, there exists \(y \in {\widehat{K}}\) such that \(\langle v, y-a \rangle < 0\). As \(K\subseteq _a {\widehat{K}}\), there exists \(\epsilon > 0\) for which \(K\cap B^n_{a}(\epsilon ) = {\widehat{K}}\cap B^n_{a}(\epsilon )\). Now choose \(1> \eta > 0\) small enough such that \(y' := \eta y + (1-\eta )a \in B^n_{a}(\epsilon )\) . Then, by convexity, we have \(y' \in {\widehat{K}}\cap B^n_{a}(\epsilon ) = K\cap B^n_{a}(\epsilon )\). Now, we have \(\langle v, y'-a \rangle = \eta \langle v, y-a\rangle < 0.\) But, as \(y' \in K\), this contradicts the assumption that \(v \in N_{K}(a)\). \(\square \)

Proof (of Proposition 1)

For simplicity, we assume here \(f(a) = 0\), which is without loss of generality by Remark 1. Consider the quadratic polynomial g from (6):

where \(\gamma := \gamma _{{{\widehat{K}}}, {f}}\) is defined in (5). By Taylor’s theorem (Theorem 1), we have that \(g(x) \ge f(x)\) for all \(x \in {\widehat{K}}\), and clearly \(g(a) = f(a)\). That is, g is an upper estimator for \(f\) on \({\widehat{K}}\), exact at a (cf. Lemma 4). We proceed to show that

We start by selecting a degree 2r sum-of-squares polynomial \(\widehat{q_{r}}\) satisfying

We may then rescale \(\widehat{q_{r}}\) to obtain a density function \(q_{r} \in \Sigma _r\) on \(K\) w.r.t. \(w_{}\) by setting

By assumption, \(w_{}(x) \le \widehat{w_{}}(x)\) for all \(x\in {{\,\mathrm{int}\,}}{K}\). Moreover, \(g(x) \ge f(a) = 0\) for all \(x \in {{\,\mathrm{int}\,}}{K}\). This implies that

and thus it suffices to show that \(\int _K\widehat{ q_{r}}(x) w_{}(x)dx \ge \frac{1}{2}m_a\). The key to proving this bound is the following lemma, which tells us that optimum sum-of-squares densities should assign rather high weight to the ball \(B^n_{\epsilon }(a)\) around a. \(\square \)

Lemma 8

Let \(\epsilon > 0\). Then, for any \(r \in {\mathbb {N}}\), we have

Proof

By Lemma 1, we have \(\nabla f(a) \in N_{K}(a)\) and so \(\nabla f(a) \in N_{{\widehat{K}}}(a)\) by Lemma 7. As a result, we have \(g(x) \ge \gamma ||x-a||^2\) for all \( x \in {\widehat{K}}\) (cf. Lemma 4). In particular, this implies that \(g(x) \ge \gamma ||x-a||^2 \ge \gamma \epsilon ^2\) for all \(x \in {\widehat{K}}{\setminus } B^n_{\epsilon }(a)\) and so

The statement now follows from reordering terms. \(\square \)

As \(K\subseteq _a {\widehat{K}}\), there exists \(\epsilon _1 > 0\) such that \(B^n_{\epsilon _1}(a) \cap K= B^n_{\epsilon _1}(a) \cap {\widehat{K}}\). As \(\widehat{w_{}} \preceq _{a} w_{}\), there exist \(\epsilon _2 > 0\), \(m_a > 0\) such that \(m_a \widehat{w_{}}(x) \le w_{}(x)\) for \(x \in B^n_{\epsilon _2}(a) \cap {{\,\mathrm{int}\,}}{K}\). Set \(\epsilon = \min \{\epsilon _1, \epsilon _2 \}\). Choose \(r_0 \in {\mathbb {N}}\) large enough such that \(E^{({r})}_{{{\widehat{K}}, \widehat{w_{}}}}({g}) < {\epsilon ^2\gamma \over 2}\) for all \(r\ge r_0\), which is possible since \(E^{({r})}_{{{\widehat{K}}, \widehat{w_{}}}}({g})\) tends to 0 as \(r\rightarrow \infty \). Then, Lemma 8 yields

for all \(r \ge r_0\). Putting things together yields the desired lower bound:

for all \(r \ge r_0\). \(\square \)

Corollary 1

Let \(K\subseteq {\widehat{K}}\subseteq {\mathbb {R}}^n\), let \(a \in K\) be a global minimizer of \(f\) on \(K\), and assume that \(K\subseteq _a {\widehat{K}}\). Let \(w_{}, \widehat{w_{}}\) be two weight functions on \(K, {\widehat{K}}\), respectively. Assume that \(\widehat{w_{}}(x) \ge w_{}(x)\) for all \(x \in {{\,\mathrm{int}\,}}{K}\) and that \(\widehat{w_{}} \preceq _{} w_{}\). Then there exists an upper estimator g of \(f\) on \({\widehat{K}}\), exact at a, such that

for all \(r \in {\mathbb {N}}\) large enough. Here \(m > 0\) is the constant defined by (8).

3.3 The unit cube

Here we consider optimization over the hypercube \(K=[-1,1]^n\) and we restrict to reference measures on K having a weight function of the form

with \(\lambda >-1\). The following result is shown in [10] on the convergence rate of the bound \(E^{({r})}_{{K, \widehat{w_{\lambda }}}}({f})\) when using the measure \(\widehat{w_{\lambda }}(x) dx \) on \(K=[-1,1]^n.\)

Theorem 2

([10]) Let \(K= [-1, 1]^n\) and consider the weight function \(\widehat{w_{\lambda }}\) from (9).

-

(i)

If \(\lambda =-\frac{1}{2}\), then we have:

$$\begin{aligned} E^{({r})}_{{K, \widehat{w_{\lambda }}}}({f}) = O\bigg (\frac{1}{r^2}\bigg ). \end{aligned}$$(10) -

(ii)

If \(n=1\) and \(f\) has a global minimizer on the boundary of \([-1, 1]\), then (10) holds for all \(\lambda > -1\).

The key ingredients for claim (ii) above are: (a) when the global minimizer is a boundary point of \([-1,1]\) then \(f\) has a linear upper estimator (recall Lemma 5), and (b) the convergence rate of (10) holds for any linear function and any \(\lambda >-1\) (see [10]).

In this section we show Theorem 3 below, which extends the above result to all weight functions \(\widehat{w_{\lambda }}(x)\) with \(\lambda \ge -\frac{1}{2}\). Following the approach in [10], we proceed in two steps: first we reduce to the univariate case, and then we deal with the univariate case. Then the new situation to be dealt with is when \(n=1\) and the minimizer lies in the interior of \([-1,1]\), which we can settle by getting back to the case \(\lambda =-\frac{1}{2}\) through applying Proposition 1, the ‘local similarity’ tool, with \(K= {\widehat{K}}= [-1,1]\).

Reduction to the univariate case Let \(a\in K\) be a global minimizer of f in \(K=[-1,1]^n\). Following [10] (recall Remark 1 and Lemma 4), we consider the upper estimator \(f(x) \le _a g(x) := f(a) + \langle \nabla f(a) , x-a \rangle + \gamma _{f,K} ||x-a||^2\). This g is separable, i.e., we can write \(g(x) = \sum _{i = 1}^n g_i(x_i)\), where each \(g_i\) is quadratic univariate with \(a_i\) as global minimizer over \([-1,1]\). Let \(q_{r}^i\) be an optimum solution to the problem (3) corresponding to the minimization of \(g_i\) over \([-1,1]\) w.r.t. the weight function \(w_{\lambda }(x_i)=(1-x_i^2)^{\lambda }\). If we set \(q_r(x) = \prod _{i=1}^n q^i_r(x_i)\), then \(q_r\) is a sum of squares with degree at most nr, such that \(\int _Kq_r(x)\widehat{w_{\lambda }}(x)dx = 1\). Hence we have

As a consequence, we need only to consider the case of a quadratic univariate polynomial \(f\) on \(K= [-1, 1]\). We distinguish two cases, depending whether the global minimizer lies on the boundary or in the interior of K. The case when the global minimizer lies on the boundary of \([-1,1]\) is settled by Theorem 2(ii) above, so we next assume the global minimizer lies in the interior of \([-1,1]\).

Case of a global minimizer in the interior of \(K=[-1,1]\) To deal with this case we make use of Proposition 1 with \(K={{\widehat{K}}}=[-1,1]\), weight function \(w(x) := w_{\lambda }(x)\) on \(K\), and weight function \({\widehat{w}}(x) := w_{-1/2}(x)\) on \({\widehat{K}}\). We check that the conditions of the proposition are met. As \({\widehat{K}}= K\), clearly we have \(K\subseteq _a {\widehat{K}}\). Further, for any \(\lambda \ge -\frac{1}{2}\), we have

for all \(x \in (-1, 1) = {{\,\mathrm{int}\,}}{K}\). As \(a \in {{\,\mathrm{int}\,}}{K}\), we also have \(w_{\lambda } \preceq _{a} w_{-1/2}\) [see Remark 3(i)]. Hence we may apply Proposition 1 to find that there exists a polynomial upper estimator g of \(f\) on \([-1, 1]\), exact at a, and having

for all \(r \in {\mathbb {N}}\) large enough. Now, (the univariate case of) Theorem 2(i) allows us to claim \(E^{({r})}_{{{\widehat{K}}, \widehat{w_{}}}}({g})= O(1/r^2)\), so that we obtain:

In summary, in view of the above, we have shown the following extension of Theorem 2.

Theorem 3

Let \(K= [-1, 1]^n\) and \(\lambda \ge -\frac{1}{2}\). Let a be a global minimizer of \(f\) on \(K\). Then we have

The constant \(m_a\) involved in the proof of Theorem 3 depends on the global minimizer a of \(f\) on \([-1,1]\). It is introduced by the application of Proposition 1 to cover the case where a lies in the interior of \([-1,1]\). When \(\lambda = 0\) (i.e., when \(w = w_0 = 1\) corresponds to the Lebesgue measure), one can replace \(m_a\) by a uniform constant \(m > 0\), as we now explain.

Consider \({\widehat{K}}:= [-2, 2] \supseteq [-1, 1] = K\), equipped with the scaled Chebyshev weight \(\widehat{w_{}}(x) := w_{-1/2}(x / 2)=(1-x^2/4)^{-1/2}\). Of course, Theorem 2 applies to this choice of \({\widehat{K}}, \widehat{w_{}}\) as well. Further, we still have \(\widehat{w_{}}(x) \ge w_{}(x) = w_{0}(x) = 1\) for all \(x \in [-1,1]\). However, we now have a uniform upper bound \(\widehat{w_{}}(x) \le \widehat{w_{}}(1)\) for \(\widehat{w_{}}\) on \(K\), which means that \(\widehat{w_{}} \preceq _{} w_{}\) on \(K\) [see Remark 3(ii)]. Indeed, we have

We may thus apply Corollary 1 (instead of Proposition 1) to obtain the following.

Corollary 2

If \(K= [-1, 1]^n\) is equipped with the Lebesgue measure then

3.4 The unit ball

We now consider optimization over the unit ball \(K=B^n\subseteq {\mathbb {R}}^n\) (\(n\ge 2\)); we restrict to reference measures on \(B^n\) with weight function of the form

where \(\lambda > -1\). For further reference we recall (see e.g. [16, §6.3.2]) or [3, §11]) that

For the case \(\lambda \ge 0\), we can analyze the bounds and show the following result.

Theorem 4

Let \(K= {B^n}\) be the unit ball. Let a be a global minimizer of \(f\) on \(K\). Consider the weight function \(w_{\lambda }\) from (11) on \(K\).

-

(i)

If \(\lambda = 0\), we have

$$\begin{aligned} E^{({r})}_{{K, w_{\lambda }}}({f}) = O\bigg (\frac{1}{r^2}\bigg ). \end{aligned}$$ -

(ii)

If \(\lambda > 0\), we have

$$\begin{aligned} E^{({r})}_{{K, w_{\lambda }}}({f}) = O_a\bigg (\frac{1}{r^2}\bigg ). \end{aligned}$$

For the proof, we distinguish the two cases when a lies in the interior of K or on its boundary.

Case of a global minimizer in the interior of \(K\) Our strategy is to reduce this to the case of the hypercube with the help of Proposition 1. Set \({\widehat{K}}:= [-1, 1]^n \supseteq {B^n}= K\). As \(a \in {{\,\mathrm{int}\,}}{K}\), we have \(K\subseteq _a {\widehat{K}}\). Consider the weight function \(w(x) := w_{\lambda }(x)=(1-\Vert x\Vert ^2)^{\lambda }\) on \(K\), and \({\widehat{w}}(x) := 1\) on the hypercube \({\widehat{K}}\). Since \(\lambda \ge 0\), we have \(w_{\lambda }(x)\le 1\le {\widehat{w}}(x)\) for all \(x \in K\). Furthermore, as \(a \in {{\,\mathrm{int}\,}}{K}\), we also have \({\widehat{w}} \preceq _{a} w\). Hence we may apply Proposition 1 to find a polynomial upper estimator g of \(f\) on \({\widehat{K}}\), exact at a, satisfying

for all \(r \in {\mathbb {N}}\) large enough. Here \(m_a > 0\) is the constant from (7). Now, Theorem 3 allows us to claim \(E^{({r})}_{{{\widehat{K}}, \widehat{w_{}}}}({g}) = O_a(1/r^2)\). Hence we obtain:

As in the previous section, it is possible to replace the constant \(m_a\) by a uniform constant \(m > 0\) in the case that \(\lambda = 0\), i.e., in the case that we have the Lebesgue measure on \(K\). Indeed, in this case we have \({\widehat{w}} = w \ (=w_0=1)\), and so in particular \({\widehat{w}} \preceq _{} w\). We may thus invoke Corollary 1 (instead of Proposition 1) to obtain

and so

Note that in this case, we do not actually make use of the fact that \(K= {B^n}\). Rather, we only need that a lies in the interior of \(K\) and that \(K\subseteq [-1, 1]^n\). As we may freely apply affine transformations to \(K\) (by Lemma 2), the latter is no true restriction. We have thus shown the following result.

Theorem 5

Let \(K\subseteq {\mathbb {R}}^n\) be a compact set, with non-empty interior, equipped with the Lebesgue measure. Assume that \(f\) has a global minimizer a on \(K\) with \(a \in {{\,\mathrm{int}\,}}{K}\). Then we have

Case of a global minimizer on the boundary of \(K\) Our strategy is now to reduce to the univariate case of the interval \([-1,1]\). For this, we use Lemma 5, which claims that f has a linear upper estimator g on K, exact at a. Up to applying an orthogonal transformation (and scaling) we may assume that g is of the form \(g(x)=x_1\). It therefore suffices now to analyze the behaviour of the bounds for the function \(x_1\) minimized on the ball \({B^n}\). Note that when minimizing \(x_1\) on \(B^n\) or on the interval \([-1,1]\) the minimum is attained at the boundary in both cases. The following technical lemma will be useful for reducing to the case of the interval \([-1,1]\).

Lemma 9

Let h be a univariate polynomial and let \(\lambda >-1\). Then we have

where \(C_{n-1,\lambda }\) is given in (12).

Proof

Change variables and set \(u_j= {x_j\over \sqrt{1-x_1^2}}\) for \(2\le j\le d\). Then we have

and \(dx_2\dots dx_n= (1-x_1^2)^{n-1\over 2} du_2\dots du_n.\) Putting things together we obtain the desired result. \(\square \)

Let \(q_r(x_1)\) be an optimal sum-of-squares density with degree at most 2r for the problem of minimizing \(x_1\) over the interval \([-1,1]\), equipped with the weight function \(w(x):=w_{\lambda +{n-1\over 2}}(x)\). Then, its scaling \(C_{n-1,\lambda }^{-1} q_r(x_1)\) provides a feasible solution for the problem of minimizing \(g(x)=x_1\) over the ball \(K=B^n\). Indeed, using Lemma 9, we have \(\int _{B^n} C_{n-1,\lambda }^{-1}q_r(x_1)w_{\lambda }(x)dx= \int _{-1}^1q_r(x_1) w(x)dx_1=1\), and so

The proof is now concluded by applying Theorem 2(ii).

3.5 Ball-like convex bodies

Here we show a convergence rate of \(E^{({r})}_{{K}}({f})\) in \(O(1/r^2)\) for a special class of smooth convex bodies \(K\) with respect to the Lebesgue measure. The basis for this result is a reduction to the case of the unit ball.

We say \(K\) has an inscribed tangent ball (of radius \(\epsilon \)) at \(x \in \partial K\) if there exists \(\epsilon > 0\) and a closed ball \(B_{insc}\) of radius \(\epsilon \) such that \(x \in \partial B_{insc}\) and \(B_{insc} \subseteq K\). Similarly, we say \(K\) has a circumscribed tangent ball (of radius \(\epsilon \)) at \(x \in \partial K\) if there exists \(\epsilon > 0\) and a closed ball \(B_{circ}\) of radius \(\epsilon \) such that \(x \in \partial B_{circ}\) and \(K\subseteq B_{circ}\).

Definition 3

We say that a (smooth) convex body \(K\) is ball-like if there exist (uniform) \(\epsilon _{insc}, \epsilon _{circ} > 0\) such that \(K\) has inscribed and circumscribed tangent balls of radii \(\epsilon _{insc}, \epsilon _{circ}\), respectively, at all points \(x \in \partial K\).

Theorem 6

Assume that \(K\) is a (smooth) ball-like convex body, equipped with the Lebesgue measure. Then we have

Proof

Let \(a \in K\) be a global minimizer of \(f\) on \(K\). We again distinguish two cases depending on whether a lies in the interior of \(K\) or on its boundary.

Case of a global minimizer in the interior of \(K\) This case is covered directly by Theorem 5.

Case of a global minimizer on the boundary of \(K\) By applying a suitable affine transformation, we can arrange that the following holds: \(f(a)=0\), \(a = 0\), \(e_1\) is an inward normal of \(K\) at a, and the radius of the circumscribed tangent ball \(B_{circ}\) at a is equal to 1, i.e., \(B_{circ} = B^n_{1}(e_1)\). See Fig. 2 for an illustration. Now, as a is a global minimizer of \(f\) on \(K\), we have \(\nabla f(a) \in N_{K}(a)\) by Lemma 1. But \(N_{K}(a) = N_{B_{circ}}(a)\), and so \(\nabla f(a) \in N_{B_{circ}}(a)\). As noted in Remark 2, we may thus use Lemma 5 to find that \(f(x) \le _a c \langle e_1, x \rangle = cx_1\) on \(B_{circ}\) for some constant \(c > 0\). In light of Remark 1(i), and after scaling, it therefore suffices to analyze the function \(f(x) = x_1\).

Again, we will use a reduction to the univariate case, now on the interval [0, 2]. For any \(r \in {\mathbb {N}}\), let \(q_{r} \in \Sigma _r\) be an optimum sum-of-squares density of degree 2r for the minimization of \(x_1\) on [0, 2] with respect to the weight function

That is, \(q_r \in \Sigma _r\) satisfies

where the first equality relies on Theorem 2(ii). As \(x \mapsto q_{r}(x_1) / (\int _{K} q_{r}(x_1) dx)\) is a sum-of-squares density on \(K\) with respect to the Lebesgue measure, we have

We will now show that, on the one hand, the numerator \(\int _{K} x_1 q_{r}(x_1) dx\) in (14) has an upper bound in \(O(1/r^2)\) and that, on the other hand, the denominator \(\int _{K} q_{r}(x_1) dx \) in (14) is lower bounded by an absolute constant that does not depend on r. Putting these two bounds together then yields \(E^{({r})}_{{K}}({f}) = O(1/r^2)\), as desired.

The upper bound We make use of the fact that \(K\subseteq B_{circ}\) to compute:

An overview of the situation in the second case of the proof of Theorem 6

The lower bound Here, we consider an inscribed tangent ball \(B_{insc}\) of \(K\) at \(a = 0\). Say \(B_{insc} = B^n_{\rho }(\rho e_1)\) for some \(\rho > 0\). See again Fig. 2. We may then compute:

where the last inequality follows using the fact that \({1-(z/\rho -1)^2 \over 1-(z-1)^2}\ge {1\over \rho (2-\rho )}\) for \(z\in [0,\rho ]\). It remains to show that

The argument is similar to the one used for the proof of Lemma 8. By (13), there is a constant \(C>0\) such that \(\int _0^2 z q_r(z) w'(z)dz \le {C\over r^2}\) for all \(r\in {\mathbb {N}}\). So we have

which implies \(\int _0^\rho q_r(z)w'(z)dz \ge 1-{C\over \rho r^2}\ge {1\over 2}\) for r large enough.

This concludes the proof of Theorem 6. \(\square \)

Classification of ball-like sets With Theorem 6 in mind, it is interesting to understand under which conditions a convex body \(K\) is ball-like. Under the assumption that \(K\) has a \(C^2\)-boundary, the well-known Rolling Ball Theorem (cf., e.g., [17]) guarantees the existence of inscribed tangent balls.

Theorem 7

(Rolling Ball Theorem) Let \(K\subseteq {\mathbb {R}}^n\) be a convex body with \(C^2\)- boundary. Then there exists \(\epsilon _{insc} > 0\) such that \(K\) has an inscribed tangent ball of radius \(\epsilon _{insc}\) for each \(x \in \partial K\).

Classifying the existence of circumscribed tangent balls is somewhat more involved. Certainly, we should assume that \(K\) is strictly convex, which means that its boundary should not contain any line segments. This assumption, however, is not sufficient. Instead we need the following stronger notion of 2-strict convexity introduced in [4].

Definition 4

Let \(K\subseteq {\mathbb {R}}^n\) be a convex body with \(C^2\)-boundary and let \(\Psi \in C^2({\mathbb {R}}^{n}, {\mathbb {R}})\) such that \(K= \Psi ^{-1}((-\infty , 0])\) and \(\partial K= \Psi ^{-1}(0)\). Assume \(\nabla \Psi (a)\ne 0\) for all \(a\in \partial K\). The set K is said to be 2-strictly convex if the following holds:

In other words, the Hessian of \(\Psi \) at any boundary point should be positive definite, when restricted to the tangent space.

Example 1

Consider the unit ball for the \(\ell _4\)-norm:

Then, K is strictly convex, but not 2-strictly convex. Indeed, at any of the points \(a= (0, \pm 1)\) and \((\pm 1,0)\), the Hessian of \(\Psi \) is not positive definite on the tangent space. For instance, for \(a=(0,-1)\), we have \(\nabla \Psi (a)= (0,-4)\) and \(x^T\Psi ^2(a)x=12x_2^2\), which vanishes at \(x=(1,0)\in T_aK\). In fact, one can verify that K does not have a circumscribed tangent ball at any of the points \( (0, \pm 1)\), \((\pm 1,0)\).

It is shown in [4] that the set of 2-strictly convex bodies lies dense in the set of all convex bodies. For \(K\) with \(C^2\)-boundary, it turns out that 2-strict convexity is equivalent to the existence of circumscribed tangent balls at all boundary points.

Theorem 8

([5, Corollary 3.3]) Let \(K\) be a convex body with \(C^2\)-boundary. Then \(K\) is 2-strictly convex if and only if there exists \(\epsilon _{circ} > 0\) such that \(K\) has a circumscribed tangent ball of radius \(\epsilon _{circ}\) at all boundary points \(a \in \partial K\).

Combining Theorems 7 and 8 then gives a full classification of the ball-like convex bodies \(K\) with \(C^2\)-boundary.

Corollary 3

Let \(K\subseteq {\mathbb {R}}^n\) be a convex body with \(C^2\)-boundary. Then \(K\) is ball-like if and only if it is 2-strictly convex.

A convex body without inscribed tangent balls We now give an example of a convex body \(K\) which does not have inscribed tangent balls, going back to de Rham [14]. The idea is to construct a curve by starting with a polygon, and then successively ‘cutting corners’. Let \(C_0\) be the polygon in \({\mathbb {R}}^2\) with vertices \((-1, -1), (1, -1), (1, 1)\) and \((-1, 1)\), i.e., a square. For \(k \ge 1\), we obtain \(C_k\) by subdividing each edge of \(C_{k-1}\) into three equal parts and taking the convex hull of the resulting subdivision points (see Fig. 3). We then let C be the limiting curve obtained by letting k tend to \(\infty \). Then, C is a continuously differentiable, convex curve (see [6] for details). It is not, however, \(C^2\) everywhere. We indicate below some point where no inscribed tangent ball exists for the convex body with boundary C.

Consider the point \(m = (0,-1) \in C\), which is an element of \(C_k\) for all k. Fix \(k\ge 1\). If we walk anti-clockwise along \(C_k\) starting at m, the first corner point encountered is \(s_k = (1/3^k, -1)\), the slope of the edge starting at \(s_k\) is \(l_k=1/k\) and its end point is

Now suppose that there exists an inscribed tangent ball \(B_\epsilon (c)\) at the point m. Then, \(\epsilon >0\), \(c=(0,\epsilon -1)\) and any point \((x,y)\in C\) lies outside of the ball \(B_\epsilon (c)\), so that

As C is contained in the polygonal region delimited by any \(C_k\), also \(e_k\not \in B_\epsilon (c)\) and thus \( \big ({2k+1\over 3^k}\big ) ^2 + \big ({2\over 3^k}\big )^2 -{4\epsilon \over 3^k}\ge 0\). Letting \(k\rightarrow \infty \), we get \(\epsilon =0\), a contradiction.

3.6 The simplex

We now consider a full-dimensional simplex \(\Delta ^{n} := {{\,\mathrm{conv}\,}}(\{v_0, v_1, v_2, \dots , v_n\}) \subseteq {\mathbb {R}}^{n}\), equipped with the Lebesgue measure. We show the following.

Theorem 9

Let \(K= \Delta ^{n}\) be a simplex, equipped with the Lebesgue measure. Then

The map \(\phi \) from the proof of Theorem 9 for \(n=2\)

Proof

Let \(a \in \Delta ^{n}\) be a global minimizer of \(f\) on \(\Delta ^{n}\). The idea is to apply an affine transformation \(\phi \) to \(\Delta ^{n}\) whose image \(\phi (\Delta ^{n})\) is locally similar to \([0,1]^n\) at the global minimizer \(\phi (a)\) of \(g := f\circ \phi ^{-1}\), after which we may ‘transport’ the \(O(1/r^2)\) rate from the hypercube to the simplex.

Let \(F := {{\,\mathrm{conv}\,}}(v_1, v_2, \dots , v_n)\) be the facet of \(\Delta ^{n}\) which does not contain \(v_0\). By reindexing, we may assume w.l.o.g. that \(a \not \in F\). Consider the map \(\phi \) determined by \(\phi (v_0) = 0\) and \(\phi (v_i) = e_i\) for all \(i \in [n]\), where \(e_i\) is the i-th standard basis vector of \({\mathbb {R}}^n\). See Fig. 4. Clearly, \(\phi \) is nonsingular, and \(\phi (\Delta ^{n}) \subseteq [0,1]^n\). \(\square \)

Lemma 10

We have \(\phi (\Delta ^{n}) \subseteq _{\phi (x)} [0, 1]^n\) for all \(x \in \Delta ^{n} {\setminus } F\).

Proof

By definition of F, we have

and so

which is an open subset of \([0, 1]^n\). But this means that for each \(y = \phi (x) \in \phi (\Delta ^{n} {\setminus } F)\) there exists \(\epsilon > 0\) such that

which concludes the proof of the lemma. \(\square \)

The above lemma tells us in particular that \(\phi (\Delta ^{n}) \subseteq _{\phi (a)} [0,1]^n\). We now apply Corollary 1 with \(K= \phi (\Delta ^{n})\), \({\widehat{K}}= [0,1]^n\) and weight functions \(w = {\widehat{w}} = 1\) on \(K, {\widehat{K}}\), respectively. This yields a polynomial upper estimator h of g on \([0,1]^n\) having

for \(r \in {\mathbb {N}}\) large enough, using Theorem 3 for the right most equality. It remains to apply Lemma 2 to obtain:

which concludes the proof of Theorem 9. \(\square \)

4 General compact sets

In this section we analyze the error \(E^{({r})}_{{}}({f})\) for a general compact set K equipped with the Lebesgue measure. We will show the following two results: when K satisfies a mild assumption (Assumption 1) we prove a convergence rate in \(O(\log r/r)\) (Theorem 10), which improves on the previous rate in \(O(1/\sqrt{r})\) from [12], and when K is a convex body we prove a convergence rate in \(O((\log r/ r)^2)\) (Theorem 11), improving the previous rate in \(O(1/r)\) from [8]. As a byproduct of our analysis, we can show the stronger bound \(O((\log r / r)^\beta )\) when all partial derivatives of \(f\) of order at most \(\beta -1\) vanish at a global minimizer (see Theorem 14). We begin with introducing Assumption 1.

Assumption 1

There exist constants \(\epsilon _{K}, \eta _{K}> 0\) such that

In other words, Assumption 1 claims that \(K\) contains a constant fraction \(\eta _K\) of the full ball \(B^n_{\delta }(x)\) around x for any radius \(\delta > 0\) small enough. This rather mild assumption is discussed in some detail in [12]. In particular, it is implied by the so-called interior cone condition used in approximation theory; it is satisfied by convex bodies and, more generally, by sets that are star-shaped with respect to a ball.

Theorem 10

Let \(K\subseteq {\mathbb {R}}^n\) be a compact set satisfying Assumption 1. Then we have

Theorem 11

Let \(K\subseteq {\mathbb {R}}^n\) be a convex body. Then we have

Outline of the proofs First of all, if f has a global minimizer which lies in the interior of \(K\), then we may apply Theorem 5 to obtain a convergence rate in \(O(1/r^2)=O((\log r/r)^2)\) and so there is nothing to prove. Hence, in the rest of the section, we assume that f has a global minimizer which lies on the boundary of K.

The basic proof strategy for both theorems is to construct explicit sum-of-squares polynomials \(q_r\) giving good feasible solutions to the program (3). The building blocks for these polynomials \(q_{r}\) will be provided by the needle polynomials from [19]; these are degree r univariate polynomials \(\nu _{r}^{h}, {{\widehat{\nu }}}_{r}^{h}\), parameterized by a constant \(h \in (0,1)\), that approximate well the Dirac delta at 0 on \([-1, 1]\) and [0, 1], respectively.

For Theorem 10, we are able to use the needle polynomials \(\nu _{r}^{h}\) directly after applying the transform \(x \mapsto \Vert x\Vert \) and selecting the value \(h = h(r)\) carefully. We then make use of Lipschitz continuity of f to bound the integral in the objective of (3).

For Theorem 11, a more complicated analysis is needed. We then construct \(q_{r}\) as a product of n univariate well-selected needle polynomials, exploiting geometric properties of the boundary of K in the neighbourhood of a global minimizer.

Simplifying assumptions In order to simplify notation in the subsequent proofs we assume throughout this section that \(0 \in K \subseteq B^n \subseteq {\mathbb {R}}^n\), and \(f_{\min , K}= f(0) = 0\), so \(a=0\) is a global minimizer of f over K. As \(K\) is compact, and in light of Lemma 2, this is without loss of generality.

We now introduce needle polynomials and their main properties in Sect. 4.1, and then give the proofs of Theorems 10 and 11 in Sects. 4.2 and 4.3, respectively.

4.1 Needle polynomials

We begin by recalling some of the basic properties of the Chebyshev polynomials. The Chebyshev polynomials \(T_{r} \in {\mathbb {R}}[t]_r\) can be defined by the recurrence relation (4), and also by the following explicit expression:

From this definition, it can be seen that \(|T_{r}(t)| \le 1\) on the interval \([-1, 1]\), and that \(T_r(t)\) is nonnegative and monotone nondecreasing on \([1, \infty )\). The Chebyshev polynomials form an orthogonal basis of \({\mathbb {R}}[t]\) with respect to the Chebyshev measure (with weight \((1-t^2)^{-1/2}\)) on \([-1,1]\) and they are used extensively in approximation theory. For instance, they are the polynomials attaining equality in the Markov brother’s inequality on \([-1, 1]\), recalled below.

Lemma 11

(Markov Brothers’ Inequality; see, e.g., [27]) Let \(p\in {\mathbb {R}}[t]\) be a univariate polynomial of degree at most r. Then, for any scalars \(a< b\), we have

Kroó and Swetits [19] use the Chebyshev polynomials to construct the so-called (univariate) needle polynomials.

Definition 5

For \(r \in {\mathbb {N}}, h \in (0, 1)\), we define the needle polynomial \(\nu _{r}^{h} \in {\mathbb {R}}[t]_{4r}\) by

Additionally, we define the \(\frac{1}{2}\)-needle polynomial \({{\widehat{\nu }}}_{r}^{h} \in {\mathbb {R}}[t]_{4r}\) by

By construction, the needle polynomials \(\nu _{r}^{h}\) and \({{\widehat{\nu }}}_{r}^{h}\) are squares and have degree 4r. They approximate well the Dirac delta function at 0 on \([-1, 1]\) and [0, 1], respectively. In [26], a construction similar to the needles presented here is used to obtain the best polynomial approximation of the Dirac delta in terms of the Hausdorff distance.

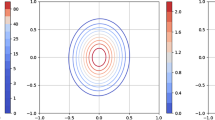

The needle polynomials satisfy the following bounds (see Fig. 5 for an illustration).

Theorem 12

(cf. [18,19,20]) For any \(r \in {\mathbb {N}}\) and \(h \in (0, 1)\), the following properties hold for the polynomials \(\nu _{r}^{h}\) and \({{\widehat{\nu }}}_{r}^{h}\):

As this result plays a central role in our treatment we give a short proof, following the argument given in [22]. We need the following lemma.

Lemma 12

For any \(r \in {\mathbb {N}}\), \(t \in [0, 1)\) we have \( T_{r}(1 + t) \ge \frac{1}{2}e^{r \sqrt{t} \log (1 + \sqrt{2}) }\ge {1\over 2} e^{{1\over 4}r\sqrt{t}}. \)

Proof

Using the explicit expression (15) for \(T_{r}\), we have

By concavity of the logarithm, we have

and so, using the above lower bound on \(T_r(1+t)\), we obtain

\(\square \)

Proof (of Theorem 12)

Properties (16), (19) are clear. We first check (17)–(18). If \(|t|\le h\) then \(1+h^2\ge 1+h^2-t^2\ge 1\), giving \(\nu _{r}^{h}(t)\le \nu _{r}^{h}(0) = 1\) by monotonicity of \(T_r(t)\) on \([1,\infty )\). Assume now \(h\le |t|\le 1\). Then \(T_r^2(1+h^2-t^2)\le 1\) as \(1+h^2-t^2\in [-1,1]\), and \(T_r^2(1+h^2)\ge 1\) (again by monotonicity), which implies \(\nu _{r}^{h}(t)\le 1\). In addition, since \(T_r(1+h^2)\ge {1\over 2} e^{{1\over 4}rh}\) by Lemma 12, we obtain \(\nu _{r}^{h}(t) \le T_r^{-2}(1+h^2)\le 4 e^{-{1\over 2}rh}\).

We now check (20)–(21). If \(t\in [0,h]\) then \({{\widehat{\nu }}}_{r}^{h}(t) \le {{\widehat{\nu }}}_{r}^{h}(0) = 1\) follows by monotonicity of \(T_{2r}(t)\) on \([1,\infty ).\) Assume now \(h\le t\le 1\). Then, \({2+h-2t\over 2-h}\in [-1,1]\) and thus \(T_{2r}^2\big ({2+h-2t\over 2-h}\big ) \le 1\). On the other hand, we have \(T_{2r}^2\big ({2+h\over 2-h}\big ) \ge 1\), which gives \({{\widehat{\nu }}}_{r}^{h}(t)\le 1\). In addition, as \({2+h\over 2-h}\ge 1+h \ge 1\), using again monotonicity of \(T_{2r}\) and Lemma 12, we get \(T_{2r}^2\big ({2+h\over 2-h}\big ) \ge T_{2r}^2(1+h)\ge {1\over 4}e^{{1\over 2}r\sqrt{h}}\), which implies (21). \(\square \)

We now give a simple lower estimator for a nonnegative polynomial p with \(p(0) = 1\). This lower estimator will be useful later to lower bound the integral of the needle and \(\frac{1}{2}\)-needle polynomials on small intervals \([-h, h]\) and [0, h], respectively.

Lemma 13

Let \(p\in {\mathbb {R}}[t]_r\) be a polynomial, which is nonnegative over \({\mathbb {R}}_{\ge 0}\) and satisfies \(p(0)=1\), \(p(t) \le 1\) for all \(t\in [0,1]\). Let \(\Lambda _{r} : {\mathbb {R}}_{\ge 0} \rightarrow {\mathbb {R}}_{\ge 0}\) be defined by

Then \(\Lambda _{r}(t) \le p(t)\) for all \(t \in {\mathbb {R}}_{\ge 0}\).

Proof

Suppose not. Then there exists \(s \in {\mathbb {R}}_{\ge 0}\) such that \(\Lambda _{r}(s) > p(s)\). As \(p \ge 0\) on \({\mathbb {R}}_{\ge 0}\), \(p(0)=1\) and \(\Lambda _{r}(t) = 0\) for \(t \ge \frac{1}{2r^2}\), we have \(0<s < \frac{1}{2r^2}\). We find that \(p(s) - p(0) < \Lambda _{r}(s) - 1 = -2r^2s.\) Now, by the mean value theorem, there exists an element \(z \in (0, s)\) such that \(p'(z) = \frac{p(s) - p(0)}{s} < \frac{-2r^2s}{s} = -2r^2\). But this is in contradiction with Lemma 11, which implies that \(\max _{t \in [0,1]}|p'(t)| \le 2r^2.\) \(\square \)

Corollary 4

Let \(h \in (0,1)\), and let \(\nu _{r}^{h}, {{\widehat{\nu }}}_{r}^{h}\) as above. Then \(\Lambda _{4r}(t) \le \nu _{r}^{h}(t) = \nu _{r}^{h}(-t)\) and \(\Lambda _{4r}(t) \le {{\widehat{\nu }}}_{r}^{h}(t)\) for all \(t \in [0, 1]\).

4.2 Compact sets satisfying Assumption 1

In this section we prove Theorem 10. Recall we assume that K satisfies Assumption 1 with constants \(\epsilon _{K}\) and \(\eta _{K}\). We also assume that \(0\in \partial K\) is a global minimizer of f over K, \(f(0)=0\), and \(K\subseteq B^n\), so that \(\epsilon _K<1\). By Lemma 6, we have \(f(x) \le _0 \beta _{{K}, {f}} \Vert x\Vert \) on \(K\). Hence, in view of Lemma 3, it suffices to find a polynomial \(q_{r} \in \Sigma _{2r}\) for each \(r \in {\mathbb {N}}\) such that \(\int _{K} {q_{r}}(x)dx = 1\) and

The idea is to set \(q_{r}(x) \sim \sigma _{r}^{h}(x) := \nu _{r}^{h}(\Vert x\Vert )\) and then select carefully the constant \(h = h(r)\). The main technical component of the proof is the following lemma, which bounds the normalized integral \(\int _K\sigma _{r}^{h}(x)\Vert x\Vert ^\beta dx\) in terms of r, h and \(\beta \ge 1\). For Theorem 10 we only need the case \(\beta =1\), but allowing \(\beta \ge 1\) permits to show a sharper convergence rate when the polynomial f has special properties at the minimizer (see Theorem 14).

Lemma 14

Let \(r \in {\mathbb {N}}\) and \(h \in (0,1)\) with \(\epsilon _{K}\ge h \ge {1}/{64r^2}\). Let \(\beta \ge 1\). Then

where \(C > 0\) is a constant depending only on \(K\).

Proof

Set \(\rho = 1/ 64r^2\), so that \(\rho \le h\le \epsilon _K\). We define the sets

Note that \({{\,\mathrm{vol}\,}}(B_h) \ge {{\,\mathrm{vol}\,}}(B_\rho ) \ge \eta _{K}\rho ^n {{\,\mathrm{vol}\,}}(B^n)\) by Assumption 1. For \(x\in B_h\), we have the bounds \(\sigma _{r}^{h}(x) \le 1\) (by (17), since \(\Vert x\Vert \le 1\) as \(K\subseteq B^n\)) and \(\Vert x\Vert ^\beta \le h^\beta \). On the other hand, for \(x\in K{\setminus } B_h\), we have the bound \(\Vert x\Vert ^\beta \le 1\), but now \(\sigma _{r}^{h}(x)\) is exponentially small (by (18)). We exploit this for bounding the integral in (22):

Combining with the following lower bound on the denominator:

we get

It remains to upper bound the last term in the above expression. By (18) we have \( \sigma _{r}^{h}(x) \le 4e^{-{1\over 2}hr}\) for any \(x\in K{\setminus } B_h\) and so

Furthermore, by Lemma 13, we have \( \sigma _{r}^{h}(x) \ge \Lambda _{4r}(\Vert x\Vert ) =1- 32 r^2\Vert x\Vert \ge {1\over 2}\) for all \(x \in B_\rho \). Using Assumption 1 we obtain

Putting things together yields

This shows the lemma with the constant \(C={8\cdot 64^n\over \eta _K}\). \(\square \)

It remains to choose \(h = h(r)\) to obtain the polynomials \(q_{r}\). Our choice here is essentially the same as the one used in [18, 26]. With the next result (applied with \(\beta = 1\)) the proof of Theorem 10 is now complete.

Proposition 2

For \(r\in {\mathbb {N}}\) and \(\beta \ge 1\), set \(h(r) =2(2n+\beta )\log r/r\) and define the polynomial \(q_{r} := \sigma _{r}^{h(r)} / \int _{K} {\sigma _{r}^{h(r)}}(x)dx\). Then \(q_r\) is a sum-of-squares polynomial of degree 4r with \(\int _{K} {q_{r}}(x)dx = 1\) and

Proof

For r sufficiently large, we have \(h(r) < \epsilon _{K}\) and \(h(r) \ge {1}/{64r^2}\) and so we may use Lemma 14 to obtain

\(\square \)

4.3 Convex bodies

We now prove Theorem 11. Here, \(K\) is assumed to be a convex body, hence it still satisfies Assumption 1 for certain constants \(\epsilon _{K}, \eta _{K}\). As before we also assume that \(0\in \partial K\) is a global minimizer of f in K, \(f(0)=0\) and \(K\subseteq B^n\).

If \(\nabla f(0) = 0\), then in view of Taylor’s theorem (Theorem 1) we know that \(f(x)\le _0 \gamma _{K,f}\Vert x\Vert ^2\) on K. Hence we may apply Proposition 2 (with \(\beta =2\)) to this quadratic upper estimator of f to obtain \(E^{({r})}_{{}}({f}) = O(\log ^2 r / r^2)\) (recall Lemma 3).

In the rest of this section, we will therefore assume that \(\nabla f(0) \ne 0\). In this case, we cannot get a better upper estimator than \(f(x) \le _0 \beta _{K,f}\Vert x\Vert \) on K, and so the choice of \(q_{r}\) in Proposition 2 is not sufficient. Instead we will need to make use of the sharper \(\frac{1}{2}\)-needles \({{\widehat{\nu }}}_{r}^{h}\). We will show how to do this in the univariate case first.

The univariate case If \(K\subseteq [-1,1]\) is convex with 0 on its boundary, we may assume w.l.o.g. that \(K= [0, b]\) for some \(b \in (0, 1]\) (in which case we may choose \(\epsilon _K=b\)). By using the \(\frac{1}{2}\)-needle \({{\widehat{\nu }}}_{r}^{h}\) instead of the regular needle \(\nu _{r}^{h}\), we immediately get the following analog of Lemma 14.

Lemma 15

Let \(b \in (0, 1]\) and \(K= [0, b]\). Let \(r \in {\mathbb {N}}\) and \(h \in (0,1)\) with \(b \ge h \ge \frac{1}{64r^2}\). Then we have

where \(C > 0\) is a universal constant.

Proof

Same proof as for Lemma 14, using now the fact that \({{\widehat{\nu }}}_{r}^{h}(x) \le 1\) on K and \( {{\widehat{\nu }}}_{r}^{h}(x) \le 4e^{-{1\over 2}\sqrt{h}r}\) on \(K{\setminus } B_h\) from (20) and (21). \(\square \)

Since the exponent in (24) now contains the term ‘\(\sqrt{h}\)’ instead of ‘h’, we may square our previous choice of h(r) in Proposition 2 to obtain the following result.

Proposition 3

Assume \(K = [0, b]\). Set \(h(r) = \big (2{\log (r^4)\over r}\big )^2= \big (8{\log r\over r}\big )^2\) and define the polynomial \(q_{r} := {{{\widehat{\nu }}}_{r}^{h(r)}}/{\int _{K} {{{\widehat{\nu }}}_{r}^{h(r)}}(x)dx}\). Then \(q_r\) is a sum-of-squares polynomial of degree 4r satisfying \(\int _{K} {q_{r}}(x)dx = 1\) and

Proof

For r sufficiently large, we have \(h(r) < b\) and \(h(r) \ge {1}/{64r^2}\) and so we may use Lemma 15 to obtain

\(\square \)

Since \(f(x)\le _0 \beta _{K,f}\cdot x\) on K we obtain \(E^{({r})}_{{}}({f})=O((\log r/r)^2)\), the desired result.

The multivariate case Let \(v := \nabla f(0) / \Vert \nabla f(0)\Vert \) and let \(w_1, w_2, \dots w_{n-1}\) be an orthonormal basis of \(v^\perp \). Then

is an orthonormal basis, which we will use as basis of \({\mathbb {R}}^n\).

The basic idea of the proof is as follows. For any \(j\in [n-1]\), if we minimize f in the direction of \(w_j\) then we minimize the univariate polynomial \({{\tilde{f}}}(t)=f(tw_j)\), which satisfies: \({{\tilde{f}}}'(0)= \langle \nabla f(0), w_j\rangle =0\). Hence, by Taylor’s theorem, there is a quadratic upper estimator when minimizing in the direction \(w_j\), so that using a regular needle polynomial will suffice for the analysis. On the other hand, if we minimize f in the direction v, then \(\min _{tv\in K}f(tv)=\min _{t\in [0,1]} f(tv)\), since \(K\subseteq B^n\) and \(v\in N_K(0)\). As explained above this univariate minimization problem can be dealt with using \(\frac{1}{2}\)-needle polynomials to get the desired convergence rate. This motivates defining the following sum-of-squares polynomials.

Definition 6

For \(r \in {\mathbb {N}}, h \in (0, 1)\) we define the polynomial \(\sigma _{r}^{h} \in \Sigma _{2nr}\) by

This construction is similar to the one used by Kroó in [18] to obtain sharp multivariate needle polynomials at boundary points of \(K\).

Proposition 4

We have \(\sigma _{r}^{h}(0)=1\) and

Proof

Note that for any \(x \in K\) we have \( 0\le \langle x, v \rangle \le \Vert x\Vert \le 1\) and \(|\langle x, w_j \rangle | \le \Vert x\Vert \le 1\) for \(j\in [n-1]\). The required properties then follow immediately from those of the needle and \(\frac{1}{2}\)-needle polynomials discussed in Theorem 12. \(\square \)

It remains to formulate and prove an analog of Lemma 14 for the polynomial \(\sigma _{r}^{h}\). Before we are able to do so, we first need a few technical statements. For \(h > 0\) we define the polytope

Note that for \(h \in (0, 1)\), the inequalities (26) and (27) can be summarized as

which means \(\sigma _{r}^{h}(x)\) is exponentially small for \(x\in K\) outside of \(P_{h}\). When instead \(x \in K\cap P_{h}\), the following two lemmas show that the function value \(f(x)\) is small.

Lemma 16

Let \(h \in (0,1)\). Then \(\Vert x\Vert \le \sqrt{n} h\) for all \(x \in P_{h}\).

Proof

Let \(x \in P_{h}\). By expressing x in the orthonormal basis U from (25), we obtain

using the definition of \(P_{h}\) for the second inequality. \(\square \)

Lemma 17

Let \(h \in (0, 1)\). Then \(f(x) \le \big (\beta _{{K}, {f}} + n\gamma _{{K}, {f}}\big ) h^2\) for all \( x \in K\cap P_{h}.\)

Proof

Using Taylor’s Theorem 1, Lemma 16 and \(\langle x,v\rangle \le h^2\) for \(x\in P_{h}\), we obtain

\(\square \)

We now give a lower bound on \(\int _{K\cap P_{h}} {\sigma _{r}^{h}}(x)dx\) [compare to (23)]. First we need the following bound on \({{\,\mathrm{vol}\,}}(K\cap P_{h})\).

Lemma 18

Let \(h \in (0,1)\). If \(h < \epsilon _{K}\) then we have: \( {{\,\mathrm{vol}\,}}(K\cap P_{h}) \ge \eta _{K}h^{2n}{{\,\mathrm{vol}\,}}(B^n)\).

Proof

Consider the halfspace \(H_v := \{ x \in {\mathbb {R}}^n : \langle v, x \rangle \ge 0\}\). As \(v \in N_{K}(0)\), we have the inclusion \(K\subseteq H_v\). We show that \(B^n_{h^2}(0) \cap H_v \subseteq P_{h}\), implying that \(B^n_{h^2}(0) \cap K\subseteq B^n_{h^2}(0) \cap H_v \subseteq P_{h}\). Let \(x \in B^n_{h^2}(0) \cap H_v\). By expressing x in the orthonormal basis U(f) from (25), we get \(\Vert x\Vert ^2=\langle v,x\rangle ^2+\sum _{j=1}^{n-1}\langle w_j,x\rangle ^2\le h^4\). Since \(x\in H_v\) and \(0<h<1\), we get \(0\le \langle v,x\rangle \le h^2\) and \(|\langle w_j,x\rangle |\le h^2\le h\), thus showing \(x\in P_h\). See Fig. 6 for an illustration. We may now apply Assumption 1 to find \({{\,\mathrm{vol}\,}}(P_{h}) \ge {{\,\mathrm{vol}\,}}(B^n_{h^2}(0) \cap K) \ge \eta _{K}h^{2n}{{\,\mathrm{vol}\,}}(B^n).\) \(\square \)

Overview of the situation in the proof of Lemma 18. Note that as long as \(v \in N_{K}(0)\), the entire region \(B^n_{h^2}(0) \cap K\) (in dark gray) is contained in \(P_{h}\)

Lemma 19

Let \(r \in {\mathbb {N}}, h \in (0, 1)\). Assume that \(\epsilon _{K}> h > \rho = {1}/{64r^2}\). Then

Proof

The integral \( \int _{K\cap P_{h}} {\sigma _{r}^{h}}(x)dx\) is equal to

\(\square \)

We are now able to prove an analog of Lemma 14.

Lemma 20

Let \(r \in {\mathbb {N}}\) and \(h \in (0,1)\). If \(\epsilon _{K}> h > {1}/{64r^2}\) then we have

where \(C'\) is a constant depending only on K.

Proof

Set \(\rho ={1}/{64r^2}\). By Lemma 17, \(f(x)\le (\beta _{K,f}+n\gamma _{K,f})h^2\) for all \(x\in K\cap P_{h}\). Moreover, by Proposition 4, we have \(\sigma ^h_r(x)\le 4e^{-{1\over 2}hr}\) for all \(x\in K{\setminus } P_{h}\). Hence,

where \(f_{\max ,K}=\max _{x\in K}f(x)\). Combining with

where we use Lemma 19 for the last inequality, we obtain

This shows the lemma, with the constant \(C'= {4\cdot 2^n \cdot 64^{2n} f_{\max ,K}\over \eta _K}\). \(\square \)

From the preceding lemma we get the following corollary, which immediately implies Theorem 11.

Corollary 5

For any \(r \in {\mathbb {N}}\), set \(h(r)= (8n+4){\log r\over r}\) and consider the polynomial \(q_{r} := {\sigma _{r}^{h(r)}}/{\int _{K} {\sigma _{r}^{h(r)}}(x)dx}\). Then \(q_r\) is a sum-of-squares polynomial of degree 4nr, which satisfies \(\int _{K} {q_{r}}(x)dx = 1\) and

Proof

For r sufficiently large, we have \(\epsilon _{K}> h(r) > {1}/{64r^2}\) and so we may apply Lemma 20, which implies directly

\(\square \)

5 Numerical experiments

In this section, we illustrate some of the results in this paper with numerical examples. We consider the test functions listed below in Table 2, the latter four of which are well-known in global optimization and also used for this purpose in [12].

We compare the behaviour of the error \(E^{({r})}_{{K}}({f})\) for these functions on different sets \(K\), namely the hypercube, the unit ball, and a regular octagon in \({\mathbb {R}}^2\). On the unit ball and the regular octagon, we consider the Lebesgue measure. On the hypercube, we consider both the Lebesgue measure and the Chebyshev measure. In each case, we compute the Lasserre bounds of order r in the range \(1 \le r \le 20\), corresponding to sos-densities of degree up to 40.

Computing the bounds As explained in Sect. 1, it is possible to compute the degree 2r Lasserre bound \(f^{(r)}_{K, \mu }\) by finding the smallest eigenvalue of the truncated moment matrix \(M_{r, f}\) of \(f\), defined by

assuming that one has an orthonormal basis \(\{p_\alpha : \alpha \in {\mathbb {N}}_r^n \}\) of \({\mathbb {R}}[x]_r\) w.r.t. the inner product induced by the measure \(\mu \), i.e., such that \( \int _Kp_\alpha p_\beta d \mu (x)=\delta _{\alpha ,\beta }\).

More generally, if we use an arbitrary linear basis \(\{p_\alpha \}\) of \({\mathbb {R}}[x]_r\) then the bound \(f^{(r)}_{K, \mu }\) is equal to the smallest generalized eigenvalue of the system:

where \(B_r := M_{r, 1}\) is the matrix with entries \(B_r(\alpha , \beta ) = \int _K p_\alpha p_\beta d\mu (x)\). Note that if the \(p_\alpha \) are orthonormal, then \(B_r\) is the identity matrix and one recovers the eigenvalue formulation of Sect. 1. For details, see, e.g., [21].

This formulation in terms of generalized eigenvalues allows us to work with the standard monomial basis of \({\mathbb {R}}[x]_r\). To compute the entries of the matrices \(M_{r, f}\) and \(B_r\), we therefore only require knowledge of the moments:

For the hypercube, simplex and unit ball, closed form expressions for these moments are known (see, e.g., Table 1 in [9]). For the octagon, they can then be computed by triangulation. We solve the generalized eigenvalue problem (28) using the eig function of the SciPy software package.

The linear case We consider first the linear case \(f(x) = f_{li}(x) = x_1\) and \(K = [-1, 1]^2\) equipped with the Lebesgue measure. Figure 7 shows the values of the parameters \(E^{({r})}_{{K}}({f_{li}})\) and \(E^{({r})}_{{K}}({f_{li}}) \cdot r^2\). In accordance with Theorem 3 [and 2(ii)], it appears indeed that \(E^{({r})}_{{K}}({f_{li}}) = O(1/r^2)\), as suggested by the fact that the parameter \(E^{({r})}_{{K}}({f_{li}}) \cdot r^2\) approaches a constant value as r grows.

The unit ball Next, we consider the unit ball \(B^2\), again equipped with the Lebesgue measure. Figure 8 shows the values of the ratio

for \(* \in \{li, qu, bo, ma, ca, mo \}\). In each case, the ratio (29) appears to tend to a constant value, suggesting that the error \(E^{({r})}_{{K}}({f_{*}})\) has similar asymptotic behaviour for \(K = [-1,1]^2\) and \(K = B^2\). This matches the result of Theorem 4 both in the case of a minimizer on the boundary (\(* \in \{li, qu \}\)) and in the case of a minimizer in the interior (\(* \in \{bo, ma, ca, mo \}\)).

Comparison of the errors of upper bounds for the functions in Table 2 computed on \([-1, 1]^2\) and the unit ball \(B^2\) w.r.t. the Lebesgue measure

The regular octagon Consider now the regular octagon (with the Lebesgue measure)

which is an example of a convex body that is not ball-like (see Definition 3). Note that as a result, the strongest theoretical guarantee we have shown for the convergence rate of the Lasserre bounds on \(O\) is in \(O( \log ^2 r / r^2)\) (see Theorem 11). Figure 9 shows the values of the ratio

for \(* \in \{li, qu, bo, ma, ca, mo \}\). As for the unit ball, the ratio (31) seemingly tends to a constant value for each of the test polynomials. This indicates a similar asymptotic behaviour of the error \(E^{({r})}_{{K}}({f_{*}})\) for \(K = [-1, 1]^2\) and \(K = O\) and suggests that the convergence rate guaranteed by Theorem 11 might not be tight in this instance.

The Chebyshev measure Finally, we consider the Chebyshev measure \(d\mu (x) = (1-x_1^2)^{-1/2}(1-x_2^2)^{-1/2}dx\) on \([-1, 1]^2\), which we compare to the Lebesgue measure. Figure 10 shows the values of the fraction

for \(* \in \{li, qu, bo, ma, ca, mo \}\). Again, we observe that the fraction (32) appears to tend to a constant value in each case, matching the result of Theorem 3.

6 Concluding remarks

Extension to non-polynomial functions Throughout, we have assumed that the function \(f\) is a polynomial. Strictly speaking, this assumption is not necessary to obtain our results. For the results in Sect. 3 and in Theorem 11, it suffices that \(f\) has an upper estimator, exact at one of its global minimizers on \(K\), and satisfying the properties given in Lemma 4. In light of Taylor’s Theorem, such an upper estimator exists for all \(f\in C^2({\mathbb {R}}^n, {\mathbb {R}})\). For Theorem 10, it is even sufficient that \(f\) satisfies \(f(x) \le f(a) + M_{f} ||x - a||\) for all \(x \in f\), where \(M_{f} > 0\) is a constant. That is, it suffices that \(f\) is Lipschitz continuous on \(K\). Finally, as shown in [11, Theorem 10], results on the convergence rate of the bounds \(f^{(r)}\) for polynomials f extend directly to the case of rational functions f.

Comparison of the errors of upper bounds for the functions in Table 2 computed on \([-1, 1]^2\) w.r.t. the Lebesgue and Chebyshev measures

Accelerated convergence results For the minimization of linear polynomials the convergence rate of the bounds \(f^{(r)}\) is shown to be in the order \(\Theta (1/r^2)\) for the hypercube [10] and the unit sphere [11]. Hence, for arbitrary polynomials, a quadratic rate is the best we can hope for. On the other hand, if we restrict to a class of functions with additional properties, then a better convergence rate can be shown. Indeed, a faster convergence rate can be achieved when the function f has many vanishing derivatives at a global minimizer. We will make use of the following consequence of Taylor’s theorem.

Theorem 13

(Taylor’s theorem) Assume \(f\in C^\beta ({\mathbb {R}}^n,{\mathbb {R}})\) with \(\beta \ge 1\). Then we have

for some constant \(\delta _{K,f}>0\).

Theorem 14

Let \(f\in C^\beta ({\mathbb {R}}^n,{\mathbb {R}})\) (\(\beta \ge 1\)) and let a be a global minimizer of f on K. Assume that all partial derivatives \((D^\alpha f)(a)\) vanish for \(1\le |\alpha |\le \beta -1\). Then, given any \(\epsilon >0\) we have

Proof

This follows as a direct application of Proposition 2. \(\square \)

This applies, e.g., for the univariate polynomial \(f(x)=x^{\beta }\) on the interval \(K=[0,1]\).

As an application we can answer in the negative a question posed in [10], where the authors asked about the existence of a ‘saturation result’ for the convergence rate of the Lasserre upper bounds, namely whether

Application to the generalized problem of moments (GPM) and cubature rules As shown in [7] results on the convergence analysis of the bounds \(E^{({r})}_{{}}({f})\) have direct implications for the following generalized moment problem (GMP):

where \(b_i\in {\mathbb {R}}\) and \(f_i\in {\mathbb {R}}[x]\) are given, and the variable \(\nu \) is a Borel measure on K. Bounds can be obtained by searching for measures of the form \(q_rd\mu \) with \(\mu \) a given Borel measure on K and \(q_r\in \Sigma _r\). Their quality can be analyzed via the parameter