Abstract

There are many studies which compared the publication and citation patterns among different research disciplines. However, one level below, potential differences within disciplines are not as well researched. Our article contributes to the research of said level by investigating the publication and citation behaviours of ten sub-disciplines of business administration and the potential differences between them. Of particular interest is a comparison of Operations Research with the other nine sub-disciplines. As research method, we conducted a scientometric analysis covering 283 professors at Austrian universities that offer a business administration program. Their publications over a ten-years period and the citations they have accumulated were retrieved from Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus. The results unveil strong differences between the analysed ten sub-disciplines, which are partially even greater than those between overall disciplines. Due to its interdisciplinary nature, we expected to see some peculiarities in the results for Operations Research. Authors from this sub-discipline are very present in WoS and Scopus. This sub-discipline achieves the highest average number of publications per researcher, and the highest self-citation rate. Apart from Operations Research, some other sub-disciplines also showed particular characteristics. This concerns especially Accounting, where publications often appear in German and in practitioner journals due to their national legalistic content. As was expected, Scopus overall has a higher coverage than WoS. However, the extent varies strongly among sub-disciplines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

It is common knowledge that different research disciplines can have quite different publication and citation behaviours (e.g., Glänzel et al. 2009; Gorraiz et al. 2014; Hayashi and Fujigaki 1999; Slyder et al. 2011; Waltman 2016; Zitt 2013). Since “business and management is made up of an umbrella of disciplines whose boundaries are fluid …” (Chartered Association of Business Schools 2021, p. 6), the question arises whether and to what extent publication and citation patterns differ among its sub-disciplines, as well.

Essentially, there are three ways to approach such an investigation when it comes to data collection: at article, journal, and author level (Amara and Landry 2012). An analysis at article level requires an (intellectual) assignment of the articles to the corresponding sub-disciplines – which can be highly time-consuming. In contrast, an assignment of journals to sub-disciplines can be supported by journal rankings such as that of the Academic Journal Guide of the Chartered Association of Business Schools (2021) where each journal is assigned to one predefined sub-discipline. However, an issue that emerges when conducting such an investigation at journal level are journals that cover different sub-disciplines, i.e., more than one sub-discipline.

The assignment of publications to sub-disciplines can be streamlined by considering the authors of the papers as a starting point (i.e., author level), since authors usually publish in ‘their’ sub-discipline (although some authors can have a wider publication spectrum and publish in more than one sub-discipline). The assignment of authors can be executed based on their membership in academic associations, e.g., The German Academic Association of Business Research (2022) which consists of 18 ‘sections’ (sub-disciplines) covering the whole spectrum of business studies. Alternatively, researchers can be assigned to a sub-discipline based on the organizational sub-units they belong to. In German-language countries’ universities with a business administration studies program, the occurrence of such organizational sub-units is common (e.g., a Department of Marketing, a Department of Human Resource Management, or a Department of Operations Research).

In our article, we follow the last approach, i.e., an investigation on author level. For our case study, we selected business administration professors who were employed at Austrian universities during the survey period. Austria was chosen due to a lack of bibliometric analyses in the field of business administration with a focus on Austria conducted so far. A further reason for the choice of Austria was that the authors are familiar with the academic and institutional situation in Austria which, e.g., enabled them to clearly define the to-be-examined group of researchers among the various categories of professors in Austria. Additionally, possible language-specific aspects could be investigated.

Taking the aforementioned considerations as a basis, the aim of this study was to find out the following:

-

the inclusion of Austrian business administration professors from Operations Research and nine other business administration sub-disciplines in Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus (research question 1);

-

the publication and citation behaviour in Operations Research and nine other business administration sub-disciplines, and the differences between them (research question 2);

-

the differences in the coverage of Operations Research and nine other business administration sub-disciplines in WoS and Scopus (research question 3).

2 State of the art

There is a high number of studies which deal with the publication and citation behaviours of different disciplines (Hayashi and Fujigaki 1999; Slyder et al. 2011; Zitt 2013; Gorraiz et al. 2014). At sub-discipline level, however, this issue has been researched to a much lesser extent (e.g., Glänzel et al. (2009), Jonkers (2009), and Kelly (2015). This is even more the case when looking at the field of business administration in German-language countries, where even rather general scientometric studies are relatively rare.

In Germany, an early conducted bibliometric and content analysis is that of Spiegel-Rösing (1977) who analysed 66 scholarly articles published in the journal Science Studies between 1971 and 1974. She showed that research productivity varies widely between institutions (see also Macharzina et al. 2004), and that the analysed articles and cited research show a strong Anglo-American bias – with 95% of the cited literature being in English. Other early research evaluations conducted in Germany are, e.g., a study by Heiber (1986) as well as a study by Pommerehne and Renggli (1986).

Macharzina et al. (1993, 2004) conducted quantitative analyses of publications of business scholars and practitioners in six major German-speaking journals from Germany, Austria, and Switzerland over the time periods from 1982 to 1991 and from 1992 to 2001. They found that all six journals have a low international exposure. When comparing the results of the two studies, Wolf et al. (2005) found that, among other things, there were only minor changes in the research performance rankings of the institutes.

Consolati (2017) analysed the research output of Austrian business administration researchers between 2006 and 2015. Using Google Scholar and Web of Science (WoS) as databases, she extracted the number of publications and citations for each professor. 79% of the 304 professors had at least one publication found in WoS, while it was 96% in Google Scholar. The distribution of publications proved to be uneven since the majority of researchers had only a few publications assigned to them. In Google Scholar (WoS), about 20% (50%) of the professors had even less than five publications listed. The citations were distributed according to a pareto distribution. In Google Scholar (WoS), the top 20% of authors received 76% (82%) of all citations.

Dyckhoff et al. (2005a, b) conducted a citation analysis to examine the international visibility of German scientists. Their collected citation frequency data between 1993 and 2002 showed that the most productive professors were those publishing in the sub-disciplines Operations Research and Production. They reasoned that publications in certain sub-disciplines such as Business Taxation, University Management, or Public Enterprises and Administrations received little to no citations due to their lack of internationalization.

Using Google Scholar as their data source, Dilger and Müller (2012) retrieved publication and citation data from 2005 to 2009 of German-speaking professors and scientists who were members of the German Academic Association of Business Research [German: Verband der Hochschullehrer für Betriebswirtschaft (VHB)]. They discovered a pareto-distribution, and found differences in citation and publication patterns between the sub-disciplines of business administration can be attributed to different scientific styles of those sub-disciplines.

In a follow-up study, Müller and Dilger (2016) extended their analysis to the whole lifework of 572 VHB members. In this analysis, the authors further used Publish or Perish (Harzing 2010, 2016), a data collection and analysis software based on Google Scholar (among other data sources). Again, the study confirmed that the 16 VHB sections have quite different publication and citation patterns. The ratio between the bottom and top performing section was 1 to 2.5 with regard to the number of citations per publication, and 1 to 4.3 with regard to the number of citations per author. Operations Research ranked top in terms of the first analysis, and third in terms of the second one (Müller and Dilger 2016, p. 42).

Vieira and Teixeira (2010) conducted an analysis based on journal citations in the sub-disciplines Finance, Marketing, and Management. Their study shows that self-citations are more prominent in Management, and even more so in Marketing. Finance can be regarded as an “autonomous, organized and settled field of research” (p. 642), but Management and Marketing are rather hybrid fields of research. Dilger and Müller (2012) also point out that there are difficulties in separating various sub-disciplines of business administration.

Meyer et al. (2012) investigated the impact of different data sources on the research performance of German-speaking researchers from Accounting and Marketing (who were members of the aforementioned German Academic Association of Business Research). Their results show that research rankings can differ considerably, and that data source selection has a higher influence on such rankings and results than indicator selection.

In another study, Perrey et al. (2010) explored the development of Financial Accounting research in four leading German academic journals between 1949 and 2007. Overall, the authors found no drastic changes in Financial Accounting research. In particular, the German accounting legislation was of great importance during their observation period. In contrast to this study, the study by Fülbier and Weller (2011) – which also dealt with Financial Accounting research – was not solely based on German journals, but rather had a wider focus set. Furthermore, they conducted a citation analysis that reveals major German characteristics such as the important role of practitioner journals and legalistic sources. Although publications written in German language still play a dominant role, the number of English-language articles has increased since the 1990s.

So far, several scientometric studies on Operations Research and Management Science have been conducted, as well. Most influential is the analysis by Merigo and Yang (2017) who give an overview about research in Operations Research in recent decades. They identified some of the most relevant research and some of the latest research trends. Furthermore, the most influential journals, the most productive and influential authors, and the most cited papers were determined. In another bibliometric analysis, Liao et al. (2019) focused solely on 646 highly cited papers from the Essential Science Indicators database. Among these articles, their study identified the most seminal journals, institutes, and countries/regions. Eventually, a collaboration and a topic analysis were conducted. The paper by Laengle et al. (2020) focuses on an analysis of the most productive and influential universities in WoS publications between 1991 and 2015.

There are also some scientometric analyses on Operations Research with similar study designs as the aforementioned that have a regional focus, namely Africa (Argoubi et al. 2021), Europe (Bilir et al. 2020), and Asia (Chang and Hsieh 2008), in particular China (Wu et al. 2016) and Turkey (Bilir et al. 2019). None of the mentioned scientometric studies examined the relationship of Operations Research to neighbouring fields. Furthermore, no study had a focus on Central Europe (in our case, Austria).

3 Methodology

We used a case study approach. In a first step, we identified all relevant Austrian business administration professors and assigned them to one of ten predefined sub-disciplines. Next, we retrieved both their publication and citation data from WoS and Scopus.

3.1 Identification of researchers and assignment to sub-disciplines

The population of this study consists of researchers from Austrian universities that offer a bachelor’s or master’s degree program in business administration. So-called universities of applied sciences as well as private and technical universities were excluded from this analysis.

Only individuals with a professor title (i.e., full, associate, or assistant professor) and a permanent position at a university were considered. Furthermore, each included researcher had to have a doctorate completed at the latest at the start of the observation period (i.e., 2008). This was to ensure that one of their main tasks lies in carrying out research in the form of publications. All chosen researchers had to be employed at one of six relevant Austrian universities as of 31st of December, 2016. Individuals on leave or maternity leave were considered since their leave was only temporary. However, emeritus professors and honorary professors were excluded because assigning their research performance to a university was often times not clearly ascertainable at the time of data collection. Lecturers were also excluded because they do not primarily produce research output.

Each relevant university’s homepage was visited to determine the list of business administration professors employed at each institution on the reference date. The researchers we analysed were affiliated to one of the following six institutions: 34 researchers to the School of Business, Economics and Social Sciences at the University of Graz, 41 researchers to the Faculty of Business and Management at the University of Innsbruck, 20 researchers to the Faculty of Management and Economics at the University of Klagenfurt, 48 researchers to the Faculty of Social Sciences, Economics and Business at the University of Linz, 37 researchers to the Faculty of Business, Economics and Statistics at the University of Vienna, and 103 researchers to the Vienna University of Economics and Business.

We further assigned each selected professor to one of the following nine business administration sub-disciplines: Accounting, Banking & Finance, Entrepreneurship, Human Resources, Information Systems, Marketing, Operations Research & Management Studies (hereinafter referred to as Operations Research), Organization, and Production & Logistics. Professors who we could not unambiguously assign to one of these sub-disciplines (e.g., professors of Economic History or Innovation Management) were allocated to a category titled Other. We formed these ten sub-disciplines specifically for this empirical study, and they are based on existing subdivisions such as those of the German Academic Association of Business Research, with a consideration of the chosen universities’ department structure. We performed a case-related subdivision due to the heterogeneity of the existing subdivisions. We also did not want to have too many sub-disciplines, and instead kept the number low so that there is a sufficient number of researchers assigned to each sub-discipline to enable meaningful comparisons between sub-disciplines. In this sense, the category Other serves as a ‘reservoir’ for rather seldomly mentioned subdivisions such as Tourism, Sustainability Management, Public Management, Non-profit Management, International Management, Innovation Management, Cooperative Management, Change Management, Gender Management, University Management, Corporate Governance, and Behavioural Management. In a first step, we identified relevant departments at the six chosen universities (or – in case further within-university subdivisions existed – sub-units of those relevant departments) that corresponded to our ten sub-disciplines. For pragmatic reasons, we assigned individual researchers to sub-disciplines based on their department affiliation.

According to Daniel (2004), at least three to five years should be covered in a research evaluation in order to eliminate outliers. Since several bibliometric studies have used a time span of ten years – seeDyckhoff et al. 2005b); Macharzina et al. (2004); Zumelzu and Presmanes (2003); Sievert and Haughawout (1989) – we also decided to set the time span for our study to ten years. Since our data retrieval took place in early 2019, we could not fully consider publications assigned to 2018 due to the lag in publishing, so we instead set the time frame to 2008 to 2017. As a consequence, also more recent publications had a higher chance of getting cited.

As we intended to conduct not only a publication analysis but also a citation analysis, we considered only three data sources: Scopus, WoS, and Google Scholar. We chose WoS and Scopus to conduct a supplementary retrieval and analysis because compared to Google Scholar, WoS and Scopus are primarily designed to capture citations, and both provide tools to uniquely identify authors (Mingers and Lipitakis 2010). In contrast to WoS and Scopus, Google Scholar is not a bibliometric database. For instance, there are no dedicated (search) fields for the affiliation or the research area (Harzing 2010, 2016). This makes it difficult to distinguish between authors with the same name. Another problem is that single publications can be included more than once in a non-consistent way (Müller and Dilger 2016). Furthermore, many citation counts are from lower quality documents which is why the higher citation counts of Google Scholar reduce the extent to which they reflect scholarly impact (Martín-Martín et al. 2018, p. 1175). As a consequence, the data quality is deemed much higher in WoS and Scopus than in Google Scholar (Aguillo 2011; Dorsch 2017; Baas et al. 2020; Birkle et al. 2020), although there have been improvements since the first software reviews by Jacso (2006, 2008). Nevertheless, Halevi et al. (2017) conclude in their more recent survey that Google Scholar cannot serve “as a sole source of literature retrieval or scholarly benchmarking because of its quality assurance and lack of transparency about the resources it covers” (p. 830).

We are aware that due to the selection of our data source, our study does not cover all publications of the analysed sub-disciplines. This is in particular striking when comparing database coverage to personal publication lists. For example, Dorsch et al. (2018) investigated authors from the scientific committee of the International Society of Scientometrics and Informetrics and demonstrated that, on average, only less than half of their publications were included in WoS. This proportion was slightly higher for Scopus (63%). In another publication, Hilbert et al. (2015) showed that this percentage might be even lower for German-language researchers, depending on the discipline. In their study, the proportion of covered publications of German-language information scientists were only 15% in WoS, and 31% in Scopus. Despite these results, we used WoS and Scoups as data sources because the focus of our study was less on completeness but rather on the differences between the sub-disciplines with regards to their participation in international science communication.

For each researcher, we retrieved data of all available articles and reviews with a publication date between 2008 and 2017 from WoS and Scopus. Our retrieval lasted from January to April 2019, and we only retrieved articles and reviews published in academic journals (Toutkoushian et al. 2003). Although publishing, e.g., a book can enhance an academic’s reputation, it is difficult to derive an objective quality measure due to the heterogeneous nature of books and publishers (Verleysen and Engels 2018). Mainstream academic journals, in contrast, provide a valid context for a reliable measure of quality.

3.2 Data collection in WoS

In WoS, we used the Web of Science Core Collection (Aksnes and Sivertsen 2019; Clarivate 2023) which includes the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) (Clarivate 2022a), Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE) (Clarivate 2022b), Arts & Humanities Citation Index (AHCI) (Clarivate 2022c), and Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI) (Clarivate 2022d), out of which we only considered the SSCI and the SCIE for our retrieval of publication and citation data. The following paragraphs explain this choice.

In general, incompleteness is a fundamental problem of any database. Despite the SSCI being incomplete when it comes to the coverage of German-language publications in the business administration field, we still chose this index because it includes international journals relevant to said field (Dilger and Müller 2012; Vera-Baceta et al. 2019). We further included the SCIE because the SSCI focuses only on social sciences while the SCIE places emphasis on natural sciences in particular (Dyckhoff et al. 2005b). By including the SCIE in this study, we expected to enlarge the coverage of publications from business administration fields particularly linked to natural sciences, thus Operations Research, Production & Logistics, and Information Systems (Dyckhoff et al. 2005b; Dyckhoff and Schmitz 2007).

We did not include the AHCI due to its focus on humanities and on cultural and art studies. Dyckhoff et al. (2005b) already showed in their preliminary study that the AHCI contained practically no relevant citations for their bibliometric study of the visibility of German-speaking business administration professors in international research.

We did not include the ESCI, either, because it only launched in 2015 and its content only dates from 2005 to the present (Clarivate 2023).

For our initial search query in WoS, we used the WoS field tag ‘AU’ (‘author’) and the fore- and surname of each professor. We omitted middle initials and further forenames as they might limit the number of hits due to name variations in the literature published by the authors (Dilger and Müller 2012).

Furthermore, we used Boolean operators in our search queries because just like in the case of, e.g., the Swedish language (Kronman et al. 2010), bibliometric studies of German-language authors face some difficulties when it comes to using names with diacritics and other special signs as input. In the German language, special letters such as ä, ö, ü, and ß are common occurrences in names. However, since no diacritics are registered in the WoS database, letters such as ä can end up as a or ae, and ö as o or oe. Therefore, when such special letters occurred in author names, we used the Boolean operator ‘OR’ in our search queries and combined possible different variations of the same name. We further used the Boolean operator ‘OR’ for queries of professors with double names as well as when professors had changed their names (e.g., via marriage). This was done to include all name variants in our search queries so that an author’s articles published under a previous name were not left out.

3.3 Data collection in Scopus

We conducted our data collection in Scopus in a manner as similar as possible to WoS so that we could compare the results of both databases. Just like in WoS, our search queries in Scopus contained Scopus field codes and – when needed – Boolean operators. For each researcher, we conducted initial search queries using both the field codes ‘Author Name’ and ‘Author’ to find out their Scopus author-ID.

In case of a search query having suspiciously long result lists, we performed publication list verifications (with publication lists pulled from external, publicly available online sources) and checked the listed affiliation in Scopus to identify the corresponding author-ID in the Scopus database. For some professors, we found two or more author-IDs in the database, in which case both were included via Boolean operators in the respective final search query. (Some common reasons we found for authors to have two or more author-IDs in Scopus were typing errors in their name, but also name variants as well as database entry errors such as their name being listed as ‘[surname], [first name initial]’ and then again as ‘[surname], [full first name]’.)

4 Results

Figures 1 and 2 show that the underlying bibliographic data is unevenly distributed in WoS and Scopus, which is quite common for this kind of data (see, e.g., Dyckhoff and Schmitz (2007). Compared to our study’s publication distribution (Fig. 1), the citation distribution (Fig. 2) is even more skewed, with the top-20% of the professors found in WoS (i.e., 45 out of 227 individuals) receiving 71% of all WoS citations, and the top-20% of the professors found in Scopus (i.e., 48 out of 240 individuals) accumulating 70% of all Scopus citations. Müller and Dilger (2016) identified an even more skewed citation distribution for data from Google Scholar, according to which 20% of all researchers received 78% of all citations.

In the following, we first show the results of our publication analysis as we discuss the professors’ overall inclusion in the two databases as well as their retrieved numbers of publications from both databases. Thereafter, we present the results of our citation analysis, once more highlighting the differences between the two databases. In both analyses, we also present the differences between the ten sub-disciplines.

4.1 Publication analysis

4.1.1 Number of professors with at least one publication in WoS and Scopus per sub-discipline

First of all, we provide an overview of the size of the ten sub-disciplines in our sample. As can be seen in the column titled ‘total number’ in Table 1, there are quite a few size differences in the number of assigned professors. The largest sub-disciplines, besides Other, are Accounting and Banking & Finance which together make up more than 30% of the sample. In contrast, Entrepreneurship, Human Resources, and Organization are the smallest sub-disciplines, constituting only 13% of the sample. As is also exhibited, Operations Research has a certain importance in Austrian business schools with regard to staff numbers. With 22 professors, it has more staff than each of the three latter mentioned sub-disciplines.

The column titled ‘with docs found’ in Table 1 reveals for how many of the researchers we were able to retrieve at least one publication in WoS and in Scopus in each sub-discipline. As was expected, this coverage is slightly higher in Scopus than in WoS, both overall – 85% (i.e., 240 out of 283 professors) see at least one publication retrieved from Scopus – as well as in six out of ten sub-disciplines. In WoS, 80% (i.e., 227 professors) are covered. Those numbers align with the results by Šember et al. (2010), Aksnes and Sivertsen (2019), and Vera-Baceta et al. (2019) who also found that Scopus achieves slightly higher coverage values. At professor level (which is relevant for this study), we find the overlap between WoS and Scopus to be relatively high. Out of the 56 professors with no documents found in WoS (refer to the column ‘with no docs found – absolute no.’ in Table 1), 38 (i.e., 68%) also have no documents found in Scopus. And out of the 43 professors for whom we found no documents in Scopus, 38 (i.e., 88%) had no documents found in WoS, either.

The coverage in the two databases varies strongly across the sub-disciplines. For more than one third of the researchers assigned to Accounting, we found no publications in neither WoS nor Scopus. The no publications-proportions for Banking & Finance were nearly one third in WoS, and almost one quarter in Scopus. Production & Logistics and Operations Research are among the sub-disciplines with the highest coverage – with only 5% of scholars assigned to these two sub-disciplines having no documents found in the two databases. Information Systems sees a noticeably higher coverage in Scopus than in WoS – with only 3% of all assigned professors having no publication found in Scopus compared to 13% in WoS.

4.1.2 Number of publications in WoS and Scopus

In our analysis, we used both full counting and adjusted counting. Full counting means that co-authored papers were fully assigned (counted as one) to each author. In contrast, adjusted counting means that each author received only a 1/n publication fraction, given that they had n co-authors. (In case of citations, the absolute number of citations was multiplied by 1/n.)

In total, we retrieved 2,530 documents from Scopus compared to 1,937 documents from WoS (see Table 2) when full counting is applied. Thus, we retrieved 31% more documents from Scopus. This percentage remains the same when co-authorship proportions are considered equally (i.e., when adjusted counting is applied).

Due to different numbers of assigned professors in our ten sub-disciplines (see Table 1), we calculated the average number of publications per professor for each sub-discipline, and listed our results in Table 3. Our results reveal that the tendentially mathematics-based sub-disciplines, i.e., Operations Research and Production & Logistics, lead the rankings in WoS and Scopus – both when full and adjusted counting is applied. The two lowest ranking sub-disciplines are Accounting and Banking & Finance. We found some vast differences between those two highest and lowest ranking sub-disciplines. For example, in WoS, a professor assigned to Accounting published only 2.6 publications on average (full counting applied) in our set ten-year period, while the corresponding output for a professor assigned to Operations Research was 14.7 publications, which is 5.7 times higher. When fractional (i.e., adjusted) counting is applied, this ratio slightly drops to 4.9. These ratios are also slightly lower for Scopus (4.0 with full counting, and 3.6 with fractional counting applied). All other sub-disciplines are more or less closely above or below the total mean values.

In their studies, Dilger and Müller (2012) and Müller and Dilger (2016) also show that the average publication values can vary quite strongly between different sub-disciplines of business administration. The ratio between the sub-disciplines in terms of the minimum and maximum average publications was slightly lower (1 to 5.3) in their second study. However, since they used a different categorization than we did, and since they collected data from Google Scholar – which also considers other document types besides journal articles – their results cannot be directly compared to ours. In the study by Meyer et al. (2012) who analysed the research performance of accounting and marketing researchers, the ratio between those two sub-disciplines was lower. In WoS, a marketing researcher had nearly two times more publications, and in Scopus slightly more than two times.

4.1.3 Co-authorship and publication language in WoS and Scopus

To further investigate potential differences in publication cultures, we performed two additional analyses: by co-authorship and by publication language. When analysing the number of co-authors per publication, we found most sub-disciplines to be relatively close to the total average number which is 3.1 co-authors per publication both in WoS and Scopus (see Table 4). Only Accounting (with an average of 2.4 co-authors in WoS and 2.6 in Scopus) deviates more strongly to the bottom, while Entrepreneurship and Other (with respectively 3.7 and 3.6 co-authors both in WoS and in Scopus) score clearly above the total average of 3.1. One Operations Research publication has on average 2.8 co-authors in WoS and Scopus, which is slightly below the total average. Overall, we find the various sub-disciplines’ co-authorship values in WoS to be very similar to those in Scopus.

As mentioned before, the vast majority of the publications determined for our study in WoS and Scopus were written in English (95.4% and 92.6%). Our findings align with those of Aksnes and Sivertsen (2019) as well as Vera-Baceta et al. (2019) who also found deficiencies regarding the coverage of non-English publications in WoS and Scopus. Nevertheless, it may happen that non-English-language publications have a higher share in particular sub-disciplines. This was the case for Accounting and Human Resources since a few of their German-language journals that see frequent publication are included in WoS and Scopus. As a consequence, the proportion of German-language articles assigned to Accounting was 13% (17 out of 126 publications) in WoS, and 12% (22 out of 189 publications) in Scopus, and of those assigned to Human Resources, 8% in WoS (5 out of 60 publications) and even 19% in Scopus (16 out of 85 publications). Meyer et al. (2012) identified an even higher proportion of German-language publications for Accounting both in WoS and Scopus. Concerning the other sub-disciplines, we identified a particular low proportion of German-language publications for Marketing, Production & Logistics, Entrepreneurship, Banking & Finance and Operations Research in WoS, and for Operations Research, Entrepreneurship, and Marketing in Scopus. The total average share of German publications (all sub-disciplines) is low in both databases (only 1.9% in WoS, and 3.8% in Scopus).

4.1.4 Number of publications in publication lists and their inclusion in WoS

In order to find possible reasons for the differences in terms of inclusion in the two databases (see Table 1) and in terms of publications per researcher (see Table 3), we determined the relevant publications (journal articles) on the basis of the researchers’ personal publication lists. For reasons of effort and data availability, this supplementary data collection was limited to the last three years of our analysis period (2015–2017). For the articles determined in this way, we then analysed their publication language and their coverage in WoS.

As is indicated in Table 5, 31% of the total number of journal articles found in personal publication lists published in 2015 to 2017 were written in German language. Accounting is the sub-discipline with the highest proportion of German-language publications (75%). In contrast, all publications by professors from Operations Research were written in English. Other sub-disciplines in which the publication language is primarily English are Information Systems (91%), Entrepreneurship (90%), Organization (87%) and Production & Logistics (85%). There is a strong negative correlation between publication language (German in %) and coverage in WoS (in %) (Pearson’s r = -0.97), which is not surprising. In the study by Vera-Baceta et al. (2019), the share of English-language publications was 95.4% in WoS (and 92.6% in Scopus) for publications published in 2018.

While we considered the whole sub-discipline of Accounting in our study, Fülbier and Weller (2011) analysed only one sub-sector, namely (German) Financial Accounting research, between 1950 and 2005. They found that the vast majority of the research was written in German, although the proportion of English-language publications has strongly increased since the 1990s. One reason for the high proportion of German-language publications in the field of Accounting is that it is often viewed as ‘local’ (national) research, characterized by national specifics and national clusters of researchers (Meyer et al. 2012). However, this should primarily be the case with Financial Accounting, which includes Taxation (Clermont and Schmitz 2008), but not with Management Accounting. In order to check this, we divided our analysed Accounting professors (and their publications) into Financial Accounting professors and Management Accounting professors. And indeed, we found that 91% of the Financial Accounting publications (based on the personal publication lists for the years 2015 to 2017) were written in German, and only 7% of them were included in WoS. On the contrary, our results for the Management Accounting publications (37% were German-language publications and 42% were included in WoS) were closer to the other sub-disciplines.

4.2 Citation analysis

Nearly all of our professors with publications found in WoS and Scopus also received citations for their publications. Only 3% (i.e., 7 out of 227) of the researchers who had at least one publication found in WoS, and 6% (14 out of 240) of the researchers who had at least one publication found in Scopus had no citations retrieved for their found publications.

4.2.1 Number of citations and self-citation rate

The 1,937 publications that we retrieved from WoS accumulate a total of 38,827 citations (including self-citations), out of which only 3.6% (i.e., 1,412 citations) were self-citations (see Table 6). In Scopus, the 2,530 publications we retrieved accumulate a total of 58,301 citations, with a self-citation rate of 12.3%, thus more than 3 times higher than that in WoS. The reason why our results show a higher self-citation rate in Scopus compared to WoS is that Scopus lists self-citations for all co-authors, while self-citations in WoS are only listed for that (co-)author whose publications were retrieved. Since one publication has, on average, three co-authors (see Subsect. 4.1.3), we expected the self-citation rate in Scopus to also be approximately three times higher.

Table 6 further reveals that the self-citation rates also differ greatly between the sub-disciplines. Information Systems and Operations Research have the highest self-citation rates in both databases, supplemented by Human Resources in Scopus. In contrast, Entrepreneurship is the sub-discipline with the (second) lowest self-citation rates in both databases, supplemented by Accounting and Other in WoS, and by Production & Logistics in Scopus.

Operations Research received the third most citations in WoS (4,959) and the fifth most citations in Scopus (6,599). This is in strong contrast to Dyckhoff et al. (2005b), according to which members from this section accounted for 39% of all VHB citations. A possible explanation for the big difference could be that they only considered articles for their study which were cited more than 20 times.

4.2.2 Citations per publication and per researcher

In WoS, we find that throughout the whole observation period (see Table 7), one publication receives on average 20 citations (including self-citations), and that one professor receives on average 137.2 citations (considered professors without any publication, as well). The corresponding values are higher in Scopus – with 23 citations per publication, and 206 citations per researcher.

When comparing the ten sub-disciplines by their average number of citations per publication (see column ‘per publication’ in Table 7), we observed some differences: In both databases, a publication of a researcher from Entrepreneurship received the most citations (i.e., 41.8 average citations per publication in WoS, and 46 in Scopus), followed with some distance by Marketing (i.e., 30.5 average citations per publication in WoS, and 30.4 in Scopus). The three bottom ranked sub-disciplines by average citations per publication in WoS (Scopus) are also the same in both databases: Accounting with 11.3 (11.0), Human Resources with 11.1 (11.1), and Banking & Finance with 13.6 (13.5). The low ranking of Accounting and Human Resources might be due to their high proportions of German-language articles (see Subsect. 4.1.2 and 4.1.3), which is why they do not have the same chances of getting cited. This partially confirms the study by Dyckhoff et al. (2005b) who reasoned that possibly due to a lack of internationalization, Business Taxation received no citations. A comparison of the top and bottom ranked sub-disciplines reveals that a publication from the top ranked sub-discipline (i.e., Entrepreneurship) receives, on average, 3.8 (4.2) times more citations than one from the bottom ranked (i.e., Human Resources or Accounting) in WoS (Scopus). Also, Dilger and Müller (2012) and Müller and Dilger (2016) identified more or less big differences in the average number of citations per paper between the different sub-disciplines. However, the disparity was slightly lower.

We see similar ranking orders when ranking the sub-disciplines by the average number of citations per researcher (see column ‘per researcher’ in Table 7) – however, with the ratios being higher. We find that, on average, a professor assigned to Entrepreneurship is 12 times more often cited than one assigned to Accounting. Operations Research performs better in this ranking both in WoS (third rank) and Scopus (fourth rank) compared to the rankings per publication.

For a rough check of the different citation numbers per publication by sub-disciplines in WoS, we used the Journal Citation Reports (JCR) (Clarivate 2022f) following an approach by Dyckhoff and Schmitz (2007). The JCR provide a yearly citation overview by journal as well as by so-called subject category. These subject categories, however, do not correspond to the ten sub-disciplines we set for our study, but are instead usually one aggregation level higher. The five subject categories from the JCR relevant for our study are listed in Table 8. It should be noted that there is partially a considerable overlap between some of the JCR subject categories – in particular between [Business] and [Management]. In our study, our sub-disciplines Information Systems and Operations Research correspond to the JCR subject categories [Operations Research & Management Science] and [Computer Science, Information Systems], while our study’s sub-disciplines Accounting and Banking & Finance fall primarily into JCR’s [Business, Finance]. The rest of our study’s sub-disciplines are mainly covered by JCR’s [Business] and [Management], with the exception of Marketing which is primarily covered by [Business]. (In Table 8, the column titled ‘Our study’s ten sub-disciplines’ correspondence to JCR’s subject categories’ lists these correspondences).

In order to provide a very rough approximation for the different citation patterns of the sub-disciplines, we used the Impact Factor (IF) for the year 2020 (Clarivate 2022e), which indicates how many times the articles from the previous two publication years (i.e., 2018 and 2019) were cited in the (following) citation year (i.e., 2020). The so-called Aggregate Impact Factor (AIF) (listed in Table 8) takes into account the number of citations to all journals in a subject category, and the number of articles from all journals in a subject category (Clarivate 2022f).

The low citation per publication values for Accounting and Banking & Finance (see Table 7) partially align with the low AIF (3.2) for the subject category [Business, Finance] (see Table 8). [Computer Science, Information Systems] and [Operations Research & Management Science] also have rather low AIFs (see Table 8), which is likewise reflected by a low citation per publication value and, consequently, low rankings for Information Systems and Operations Research in WoS (see Table 7). Interestingly, the average number of citations per publication of Human Resources (see Table 7) does not align with the according AIF (see Table 8) for [Business] and [Management].

Ultimately, one explanation for the partially vast differences in citation patterns is the particular sample in our study (i.e., Austrian business administration professors). A reason for the low average citation counts per researcher and per publication in Accounting but also in Banking & Finance is that more than one third of the researchers assigned to this sub-discipline had no publications found in WoS. In the case of Accounting, a stronger national research orientation and consequently higher German-language publication numbers are further reasons for the lower citation values found. Human Resources is also a sub-discipline with a high proportion of German-language articles, and it sees more than one quarter of its researchers not included in WoS (see Table 1).

4.3 Coverage comparison between WoS and Scopus

The previous sub-sections have shown that Scopus has a higher coverage for both publications and citations than WoS. We also found strong correlations between WoS and Scopus with regard to the number of publications (Pearson: 0.94, Spearman: 0.91), citations (Pearson: 0.93, Spearman: 0.94), and average number of citations per article (Pearson: 0.93, Spearman: 0.87) for all researchers present in the two databases.

As is exhibited in Table 9, the extent to which the coverage is higher in Scopus depends on the sub-discipline. For instance, Scopus covers 50% more publications (when full counting is applied) in the sub-disciplines Accounting and Others, while this percentage is only 7% for Operations Research and 15% for Banking & Finance. This means that Operations Research performs better in WoS than in Scopus when being compared to the other sub-disciplines. In contrast, Accounting has a higher proportion of publications in Scopus in comparison to the other sub-disciplines. This confirms the study by Clermont and Schmitz (2008) who found big differences when it comes to the coverage of Accounting and Operations Research in WoS and Scopus. These differences between Accounting and Operations Research stemmed from many leading academic accounting journals not being indexed in WoS but in Scopus, and it algins with the study by Mongeon and Paul-Hus (2015) who found WoS to have an overall low coverage of journals from the social sciences.

A similar issue can also be observed concerning the coverage of citations in the two databases (see column ‘Citations (full counting)’ in Table 9). Here, Information Systems (94%) and Production & Logistics (89%) receive nearly double as many citations in Scopus in comparison to the mean value of all sub-disciplines (50%). This confirms the results by Meyer et al. (2012) according to which the data source selection has a stronger effect on the research performance than the indicator selection.

4.4 Peculiar results found for some sub-disciplines

Our publication and citation analyses confirm the existence of partly great differences between the various sub-disciplines of business administration. Operations Research is an interdisciplinary research area, and expected differences to other sub-disciplines are also confirmed by the results of our scientometric analysis. Professors from this sub-discipline have the highest average number of publications per researcher in both databases (see Table 3). It could be argued that ‘mathematics and formulas’ are the ‘primary language’ here, independent from the authors’ actual mother tongue. Consequently, the language barrier is rather low here (since WoS and Scopus cover primarily English-language journals) compared to ‘text-heavy’ sub-disciplines. Professors assigned to Operations Research further have the highest self-citation rate in WoS, and the third highest self-citation rate in Scopus (see Table 6). This reflects the issue of professors from this sub-discipline referring more often to their previous work compared to (most) other sub-disciplines. This could be due to the fact that they deal with a topic for a prolonged period of time, and that they build on mathematical models.

However, more surprising were the peculiarities of a few other sub-disciplines: Accounting, Banking & Finance, Information Systems, Entrepreneurship, and Human Resources.

Our analyses reveal the strongest peculiarities for Accounting and Banking & Finance. These two sub-disciplines have a relatively high proportion of assigned professors with no publications retrieved from WoS and Scopus (see Table 1). This is one of the reasons why the citation rates per researcher in particular for Accounting are clearly lower than for the other sub-disciplines (see Table 7). Furthermore, researchers assigned to Accounting and Banking & Finance have a rather low publication output (in WoS and Scopus) compared to our other business administration sub-disciplines (see Table 2), which could be linked to their, on average, smallest number of co-authors (see Table 4). Regarding Accounting, the low publication output is also mainly due to accounting publications often times being published in German-language journals that are not included in the two databases used for this study. In our results, Accounting indeed sees the highest number of non-English language publications in the publication lists (75%) and in WoS (13%). One reason might be that several topics, e.g., taxation, often deal with national aspects. The partially stronger national focus and therefore more frequent use of German as publication language might also have led to the low citation rates (see Table 7).

Since Information Systems has strong links to Computer Science – though pursuing different goals (Hansen et al. 2019) – we had hence already expected some peculiar differences to other business administration sub-disciplines in our results. This was confirmed in that we saw more co-authors jointly publishing a paper (see Table 4), and authors citing their own work more than authors from other sub-disciplines (see Table 6). Just like in Computer Science, conferences and therefore proceedings papers play an important role in this sub-discipline’s science communication. In contrast to the WoS Core Collection (Mingers and Lipitakis 2010), proceedings papers are included in Scopus, which is why this sub-discipline’s peculiarities are more evident in Scopus than in WoS.

In our study, the sub-discipline Entrepreneurship has the lowest number of professors assigned (see Table 1). Our results show that it stands out in several aspects compared to our other sub-disciplines. Its assigned researchers accumulate a relatively high research output when full counting is applied (i.e., for only 8 assigned researchers, we retrieved a total of 83 documents from WoS, and 112 from Scopus; see Table 2). Although publications of professors assigned to this sub-discipline have the highest average number of co-authors per publication, these publications have the lowest page number counts. (We have also retrieved each publication’s page number count as part of our database research.) And although this sub-discipline has the lowest self-citation rates (see Table 6), it nevertheless receives the highest average citation counts both per researcher and per publication (see Table 7).

Human Resources (Management) has a similar size as Entrepreneurship in our sample (see Table 1), but it achieves quite different results. Besides Accounting, it has one of the highest proportions of German-language publications retrieved. Nearly one fifth of its retrieved Scopus publications are in German language. Besides Information Systems, Human Resources also has the highest self-citation rate in Scopus (i.e., over 23%; see Table 6), and it performs low by citation rate per researcher and per publication in both databases (see Table 7).

5 Conclusion and limitations

Our study shows that Operations Research and Production & Logistics are those sub-disciplines with the highest proportion of researchers included in WoS and Scopus. For 95% of Austrian professors from these two sub-disciplines, we could retrieve publications in WoS and Scopus (research question 1). Only Information Systems had a higher coverage in Scopus (97%). Our results for research question 2 confirm the claim by Dilger and Müller (2012) and Müller and Dilger (2016) that different sub-disciplines of business administration have different scientific styles and therefore also different publication and citation patterns. These differences between the sub-disciplines of business administration can end up being even greater than some differences between whole disciplines. This concerns Operations Research which is by nature close to mathematics, and which stands out in our results with its high coverage, its high number of publications per researcher, and its high self-citation rate. Other sub-disciplines with more strongly differing characteristics are Accounting, Banking & Finance, Information Systems, Entrepreneurship, and Human Resources. As our comparison with data from the Journal Citation Reports (JCR) reveals, these differences are even stronger for our sample due to national and language-specific characteristics. This is in particular true for Accounting and Banking & Finance, the publications of which are more often written in German language due to a partially stronger national focus. It follows that research performance rankings should be conducted for single sub-disciplines, and not for business administration as a whole.

A by-product of this study is the comparison between WoS and Scopus (research question 3). As was expected, our data retrieval from Scopus encompasses approximately 30% more publications than WoS, even when adjusting publication counts. This relation is even higher for our citation retrieval, with Scopus being approximately 50% more extensive than WoS. Scopus is furthermore said to have a higher share of non-English language publications compared to WoS. However, this difference was not as big in our sample as anticipated, with 1.9% of our publications retrieved from WoS being written in German, compared to 3.4% of publications retrieved from Scopus. What came as a surprise instead were the partially big differences between the databases by sub-disciplines. While Accounting and Other have 50% more publications retrieved from Scopus than from WoS, this value is only 7% for Operations Research (with full counting applied). Therefore, our study shows that the choice of data source can have a strong influence on the results of a quantitative research assessment – not only when comparing different disciplines with each other (see Mongeon and Paul-Hus 2015), but also when such an assessment is conducted at sub-disciplinary level. Accordingly, Operations Research has a better standing in comparison to the other sub-disciplines if WoS is used as a data source.

One limitation of our study concerns the determination of sub-disciplines and the assignment of researchers to those sub-disciplines. Concerning the sub-disciplines’ specifications, although we based our determination on existing classifications, we created our own categories. Concerning those categories, we agree with the feedback by one reviewer according to which instead of merely Accounting, Business Taxation (respectively Financial Accounting) should have been considered as an own sub-discipline beside Management Accounting. Furthermore, we assigned professors to sub-disciplines by using the research field (i.e., the designation) of their department or their department’s sub-unit. The actual research field of the individual professors – in the event of a discrepancy – was not considered in more detail. Although the utilization of one of the existing classifications, such as that of the German Academic Association of Business Research (2022), and an assignment of professors according to their membership in this association’s section (i.e., sub-discipline) can be a more streamlined approach, this approach would have required access to relevant member data, which was not available in our case. However, even if such a more streamlined approach is applied, the issue that a researcher can be associated with more than one section (sub-discipline) still remains.

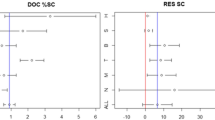

As was shown before, publications and citations follow a strong skewed distribution which is also true for many sub-disciplines. Figure 3 shows that for several sub-disciplines like Information Systems or Other, a few high performing researchers raised the total impact of the according sub-discipline. Bonaccorsi and Cicero (2016) report about a similar phenomenon when analysing research data from Italy. In their analysis, they identified a particularly high share of excellent researchers in the social sciences and humanities. Due to such distortions, certain sub-disciplines ended up with better results than other sub-disciplines [see also Dilger and Müller (2012, p. 1100)]. Such results are even more likely when the sample is relatively small – as is in our case.

Ultimately, as aforementioned, the focus of the present study was on Austria. Accordingly, one main shortcoming is that the results cannot be generalized. Therefore, we plan to conduct another study that will be performed at journal level. This additional study should yield more generalizable results at the sub-discipline level (and not only at the subject category level – which is already provided by the Journal Citation Reports).

References

Aguillo IF (2011) Is Google Scholar useful for bibliometrics? A webometric analysis. Scientometrics 91(2):343–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-011-0582-8

Aksnes DW, Sivertsen G (2019) A criteria-based Assessment of the Coverage of Scopus and Web of Science. J Data Inf Sci 4(1):1–21. https://doi.org/10.2478/jdis-2019-0001

Amara N, Landry R (2012) Counting citations in the field of business and management: why use Google Scholar rather than the Web of Science. Scientometrics 93(3):553–581. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-012-0729-2

Argoubi M, Ammari E, Masri H (2021) A scientometric analysis of Operations Research and Management Science research in Africa. Oper Res 21(3):1827–1843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12351-020-00555-9

Baas J, Schotten M, Plume A et al (2020) Scopus as a curated, high-quality bibliometric data source for academic research in quantitative science studies. Quant Sci Stud 1(1):377–386. https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00019

Bilir C, Güngör C, Kökalan Ö (2019) Bibliometric overview of operations reseach/management science research in Turkey. Sigma J Eng Nat Sci 37(3):797–811

Bilir C, Güngör C, Kökalan Ö (2020) Operations Research/Management Science Research in Europe: a bibliometric overview. Adv Oper Res. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/1607637

Birkle C, Pendlebury DA, Schnell J, Adams J (2020) Web of Science as a data source for research on scientific and scholarly activity. Quant Sci Stud 1(1):363–375. https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00018

Bonaccorsi A, Cicero T (2016) Distributed or concentrated Research Excellence? Evidence from a Lage-Scale Research Assessment Exercise. J Assoc Inf Sci Technol 67(12):2976–2992. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23539

Chang P-L, Hsieh P-N (2008) Bibliometric overview of Operations Research/Management Science research in Asia. Asia-Pacific J Oper Res 25(2):217–241. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217595908001705

Chartered Association of Business Schools (2021) AJC – Academic Journal Guide 2021. https://charteredabs.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Academic_Journal_Guide_2021-Methodology.pdf. Accessed 15 Mar 2022

Clarivate (2022a) Web of Science: Social Sciences Citation Index. https://clarivate.com/webofsciencegroup/solutions/webofscience-ssci/. Accessed 26 Mar 2022

Clarivate (2022b) Web of Science: Science Citation Index Expanded. https://clarivate.com/webofsciencegroup/solutions/webofscience-scie/. Accessed 26 Mar 2022

Clarivate (2022c) Web of Science: Arts & Humanities Citation Index. https://clarivate.com/webofsciencegroup/solutions/webofscience-arts-and-humanities-citation-index/. Accessed 26 Mar 2022

Clarivate (2022d) Web of Science: Emerging Sources Citation Index. www.clarivate.com/webofsciencegroup/solutions/webofscience-esci/. Accessed 25 Mar 2022

Clarivate (2022e) Journal Citation Reports. https://jcr.clarivate.com. Accessed 18 Mar 2022

Clarivate (2022f) Incites Journal Citation Reports Help. http://help.prod-incites.com/incitesLiveJCR/glossaryAZgroup/g4/7769-TRS.html. Accessed 18 Mar 2022

Clarivate (2023) Web of Science Core Collection. https://clarivate.com/webofsciencegroup/solutions/web-of-science-core-collection/. Accessed 26 Mar 2022

Clermont M, Schmitz C (2008) Erfassung betriebswirtschaftlich relevanter Zeitschriften in den ISI-Datenbanken sowie der Scopus-Datenbank. Z für Betriebswirtschaft 78(10):987–1010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-008-0109-9

Consolati N (2017) Eine Publikations- und Zitationsanalyse der österreichischen Betriebswirtschaftslehre auf basis der bibliometrischen Datenbanken Web of Science und Google Scholar. University of Graz

Daniel H-D (2004) Evaluation von Forschungsinstitutionen in Deutschland. Plattf – Technol – Evaluierung 10:2–6

Dilger A, Müller H (2012) Ein Forschungsleistungsranking auf der Grundlage von Google Scholar. Z Betriebswirtschaft 82(10):1089–1105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-012-0617-5

Dorsch I (2017) Relative visibility of authors’ publications in different information services. Scientometrics 112(2):917–925. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2416-9

Dorsch I, Askeridis JM, Stock WG (2018) Truebounded, Overbounded, or Underbounded? Scientists’ personal publication lists versus lists generated through Bibliographic Information Services. Publications 6(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/publications6010007

Dyckhoff H, Schmitz C (2007) Forschungsleistungsmessung mittels SSCI oder SCI-X? Die Betriebswirtschaft 67(6):638–662

Dyckhoff H, Rassenhövel S, Gilles R, Schmitz C (2005a) Beurteilung der Forschungsleistung und das CHE-Forschungsranking betriebswirtschaftlicher Fachbereiche. WiSt 34(2):62–69

Dyckhoff H, Thieme A, Schmitz C (2005b) Die Wahrnehmung deutschsprachiger Hochschullehrer für Betriebswirtschaft in der internationalen Forschung. Eine Pilotstudie zu Zitationsverhalten und möglichen Einflussfaktoren. Die Betriebswirtschaft 65:350–372

Fülbier RU, Weller M (2011) A glance at German Financial Accounting Research between 1950 and 2005: a publication and citation analysis. Schmalenbach Bus Rev 63(1):2–33

German Academic Association of Business Research (2022) German Academic Association of Business Research. https://vhbonline.org/en/about-us. Accessed 4 Mar 2022

Glänzel W, Thijs B, Schubert A, Debackere K (2009) Subfield-specific normalized relative indicators and a new generation of relational charts: methodological foundations illustrated on the assessment of institutional research performance. Scientometrics 78(1):165–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-008-2109-5

Gorraiz J, Gumpenberger C, Schlögl C (2014) Usage versus citation behaviours in four subject areas. Scientometrics 101(2):1077–1095. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-014-1271-1

Halevi, G., Moed, H. & Bar-Ilan, J. Suitability of Google Scholar as a source of scientific information and as a source of data for scientific evaluation, J Informetr, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JOI.2017.06.005 (2017).

Hansen H, Mendling J, Neumann G (2019) Wirtschaftsinformatik. De Gruyter, Berlin

Harzing AW (2010) The Publish or Perish Book: your guide to effective and responsible citation analysis. Tarma Software Research Pty, Melbourne

Harzing AW (2016) Publish or Perish 4 User’s Manual. In: Tarma Softw. Res. Ltd. https://email.uni-graz.at/owa/#path=/mail. Accessed 5 Jul 2023

Hayashi T, Fujigaki Y (1999) Differences in knowledge production between disciplines based on analysis of paper styles and citation patterns. Scientometrics 46(1):73–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02766296

Heiber H (1986) Messung universitärer Forschungsleistungen mit Hilfe der Zitatenanalyse. In: Fisch R, Daniel H-D (eds) Messung und Förderung von Forschungsleistung. Konstanz, pp 135–149

Hilbert F, Barth J, Gremm J et al (2015) Coverage of academic citation databases compared with coverage of scientific social media: personal publication lists as calibration parameters. Online Inf Rev 39(2):255–264. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-07-2014-0159

Jacso P (2006) Deflated, inflated and phantom citation counts. Online Inf Rev 30(3):297–309. https://doi.org/10.1108/14684520610675816

Jacso P (2008) Google Schlar revisited. Online Inf Rev 32(1):102–114. https://doi.org/10.1108/14684520810866010

Johannes Kepler University Linz (2022) Faculty of Social Sciences, Economics and Business Homepage. www.jku.at/en/faculty-of-social-sciences-economics-business/. Accessed 19 Oct 2022

Jonkers K (2009) Emerging ties: factors underlying China’s co-publication patterns with western european and north american research systems in three molecular life science subfields. Scientometrics 80(3):775–795. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-008-2115-7

Kelly M (2015) Citation patterns of Engineering, Statistics, and Computer Science Researchers: an internal and external citation analysis across multiple Engineering Subfields. Coll Res Libr 76(7):859–882. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.76.7.859

Kronman U, Gunnarsson M, Karlsson S (2010) The bibliometric database at the Swedish Research Council – contents, methods and indicators

Laengle S, Merigo JM, Modak NM, Yang JB (2020) Bibliometrics in operations research and management science: a university analysis. Ann Oper Res 294(1–2):769–813. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-018-3017-6

Liao, H., Tang, M., Li, Z. & Lev, B. Bibliometric analysis for highly cited papers in operations research and management science from 2008 to 2017 based on Essential Science Indicators, Omega - Int J Manag Sci, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2018.11.005 (2019).

Macharzina K, Wolf J, Oesterle M-J (1993) Quantitative evaluation of German Research output in Business Administration. Manag Int Rev 33(1):65–83

Macharzina K, Wolf J, Rohn A (2004) Quantitative evaluation of German Research output in Business Administration: 1992–2001. Manag Int Rev 44(3):335–359

Martín-Martín A, Orduna-Malea E, Thelwall M, López-Cózar ED (2018) Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus: a systematic comparison of citations in 252 subject categories. J Informetr 12:1160–1177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2018.09.002

Merigo JM, Yang JB (2017) A bibliometric analysis of operations research and management science. Omega - Int J Manag Sci 73:37–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2016.12.004

Meyer M, Waldkirch RW, Zaggl MA (2012) Relative performance measurement of researchers: the impact of data source selection. sbr 64:308–330

Mingers J, Lipitakis E (2010) Counting the citations: a comparison of Web of Science and Google Scholar in the field of business and management. Scientometrics 85(2):613–625. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-010-0270-0

Mongeon P, Paul-Hus A (2015) The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: a comparative analysis. Scientometrics 106(1):213–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1765-5

Müller H, Dilger A (2016) Wie der Forschungsschwerpunkt den Zitationserfolg beeinflusst – eine empirische untersuchung für die deutschsprachige BWL. Betriebswirtschaftliche Forsch und Prax 68(1):36–52

Perrey E, Utz Schäffer, Kramer S (2010) Rechnungslegungsforschung in deutschsprachigen wissenschaftlichen Zeitschriften. Eine Publikationsanalyse. (Financial Accounting Research in German speaking academic journals. A publication analysis). Z Betriebswirtschaft 70(6):481–494

Pommerehne WW, Renggli MFP (1986) Die Messung universitärer Forschungsleistung am Beispiel der Wirtschaftswissenschaften. In: Fisch R, Daniel H-D (eds) Messung und Förderung von Forschungsleistung. Konstanz, pp 89–134

Šember M, Utrobičić A, Petrak J (2010) Croatian Medical Journal Citation score in Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar. Croat Med J 51(2):99–103. https://doi.org/10.3325/cmj.2010.51.99

Sievert M, Haughawout M (1989) An editor’s influence on citation patterns: a case study of Elementary School Journal. J Am Soc Inf Sci 40(5):334–341. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(198909)40:53.0.CO;2-S

Slyder JB, Stein BR, Sams BS et al (2011) Citation pattern and lifespan: a comparison of discipline, institution, and individual. Scientometrics 89(3):955–966. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-011-0467-x

Spiegel-Rösing I (1977) Science Studies. Bibliometric and content analysis. Soc Stud Sci 7:97–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631277700700111

Toutkoushian RK, Porter SR, Danielson C, Hollis PR (2003) Using publications counts to measure an institution’s research productivity. Res High Educ 44(2):121–148. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022070227966

University of Graz (2023) School of Business, Economics, and Social Sciences Homepage. www.sowi.uni-graz.at/en/school-of-business-economics-and-social-sciences/. Accessed 26 Sep 2022

University of Innsbruck (2022) Faculty of Business and Management Homepage. www.uibk.ac.at/fakultaeten/betriebswirtschaft/index.html.en. Accessed 20 Oct 2022

University of Klagenfurt (2023) Faculty of Management and Economics Homepage. www.aau.at/en/wiwi/. Accessed 20 Oct 2022

University of Vienna (2023) Faculty of Business, Economics and Statistics Homepage. www.wirtschaftswissenschaften.univie.ac.at/en/. Accessed 20 Oct 2022

Vera-Baceta MA, Thelwall M, Kousha K (2019) Web of Science and Scopus language coverage. Scientometrics 121(3):1803–1813

Verleysen FT, Engels TCE (2018) How arbitrary are the weights assigned to books in performance-based research funding? An empirical assessment of the weight and size of monographs in Flanders. ASLIB J Inf Manag 70(6):660–672. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-05-2018-0110

Vieira PC, Teixeira AAC (2010) Are Finance, Management and Marketing Autonomous Fields of Scientific Research? An analysis based on Journal Citations. Scientometrics 85(3):627–646. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-010-0292-7

Vienna University of Economics and Business (2023) Homepage. https://www.wu.ac.at/en/. Accessed 26 Mar 2022

Waltman L (2016) A review of the literature on citation impact indicators. J Informetr 10(2):365–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2016.02.007

Wolf J, Rohn A, Macharzina K (2005) Institution und Forschungsproduktivität: Befunde und Interpretation aus der deutschsprachigen Betriebswirtschaftslehre. DBW 65(1):62–77

Wu DS, Xie YJ, Dai QZ, Li JP (2016) A systematic overview of operations research/management science research in mainland China: bibliometric analysis of the period 2001–2013. Asia-Pacific J Oper Res 33(6). https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217595916500445

Zitt M (2013) Variability of citation behavior between scientific fields and the normalization problem: the “citing-side” normalization in context. COLLNET J Sci Inf Manag 7(1):55–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/09737766.2013.802619

Zumelzu E, Presmanes B (2003) Scientific cooperation between Chile and Spain: joint mainstream publications (1991–2000). Scientometrics 58(3):547–558. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SCIE.0000006879.96909.ef

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the reviewers for their helpful comments.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Graz.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Sandra Boric. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Christian Schlögl, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schlögl, C., Boric, S. & Reichmann, G. Publication and citation patterns of Austrian researchers in operations research and other sub-disciplines of business administration as indexed in Web of Science and Scopus. Cent Eur J Oper Res 32, 711–736 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10100-023-00877-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10100-023-00877-x