Abstract

Objectives

Implementation of advance care planning (ACP) in people with progressive multiple sclerosis (PwPMS) is limited. We aimed to involve users (PwPMS, significant others, and healthcare professionals involved in PwPMS care) in the evaluation and refinement of a booklet to be used during the ACP conversations.

Methods

This qualitative study consisted of cognitive interviews with PwPMS and significant others and a focus group with healthcare professionals from three Italian centers. We analyzed the interviews using the framework method and the focus group using thematic analysis.

Results

We interviewed 10 PwPMS (3 women; median age 54 years; median Expanded Disability Status Scale score 6.0) and three significant others (2 women; 2 spouses and one daughter). The analysis yielded three themes: booklet comprehensibility and clarity, content acceptability and emotional impact, and suggestions for improvement. Twelve healthcare professionals (7 neurologists, 3 psychologists, one nurse, and one physiotherapist) participated in the focus group, whose analysis identified two themes: booklet’s content importance and clarity and challenges to ACP implementation. Based on analysis results, we revised the booklet (text, layout, and pictures) and held a second-round interviews with two PwPMS and one significant other. The interviewees agreed on the revisions but reaffirmed their difficulty in dealing with the topic and the need for a physician when using the booklet.

Conclusions

Appraisal of the booklet was instrumental in improving its acceptability and understandability before using it in the ConCure-SM feasibility trial. Furthermore, our data reveal a lack of familiarity with ACP practice in the Italian context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common cause of progressive neurological disability in young adults [1, 2]. Approximately 15% of people with MS have a primary progressive course at diagnosis, and an additional 35% develop secondary progressive disease after 15 years [3]. A mean reduction in life expectancy by 7–14 years has been reported, with improved figures over the last two decades [4,5,6]. Nevertheless, people with progressive MS (PwPMS) may live for many years experiencing a wide range of symptoms, impairments (including cognitive impairment, which affects 40–70% of sufferers), and comorbidities [6,7,8,9,10,11].

In this context, advance care planning (ACP) is necessary to ensure that PwPMS future care, especially at the end of life (EOL), is consistent with evidence-based practice and a person-value-centered approach [12,13,14,15]. ACP “supports adults at any age or health stage in understanding and sharing their personal values, life goals and preferences regarding treatments and future medical care” [16].

Increasing patient and public awareness of the role of ACP for improving the quality of care at the EOL is also crucial. The National Health System has a key role in providing a context for such engagement and in promoting ACP effective use [16]. Initiatives to foster the implementation of ACP have increased over the last decade and include educational programs in the healthcare setting, public awareness campaigns, and national laws [17].

Evidence from non-neurological progressive and life-threatening illnesses shows that ACP helps manage the care path, decreases unwanted life-sustaining treatments, and increases the use of hospice and palliative care [18, 19], as well as alignment with patients’ EOL preferences [19].

Nevertheless, ACP implementation has shown several challenges: it can produce an emotional burden due to thinking about death and the necessity of making plans. From healthcare professionals’ point of view, the length of time to devote to ACP discussion, the difficulty in prognostic prediction, and the disagreement about care goals among multidisciplinary team members have been reported as barriers [20, 21]. A general lack of knowledge on ACP due to inadequate training of healthcare professionals on EOL care, advance directives, and ACP has also been reported [22].

The recently published European Academy of Neurology Guideline on Palliative Care in People with Severe Progressive MS includes the following good practice statement: “It is suggested that early discussion on the future with ACP is offered to patients with severe MS” [23, 24]. This statement was based on consensus between task force members, as no evidence was found on the effectiveness of ACP in PwPMS [23,24,25]. PwPMS want to talk about their future with healthcare professionals; however, they do not have the opportunity to start these conversations [26,27,28]. The reasons are complex, and include the unpredictable trajectory of MS and the healthcare professional reluctance to discuss disease progression and care pathways at the EOL. In a qualitative study by Koffman et al., MS patients reported negative experiences of EOL-related discussions with healthcare professionals [29].

ConCure-SM is a multi-phased project aimed to construct and test the efficacy of an MS-specific ACP intervention, consisting of a training program on ACP for healthcare professionals caring for PwPMS and a booklet to be used during the ACP conversation [30]. The training program includes a residential module and an on-site module. The residential module (one-and-half day duration, continuing medical education accredited) includes a theoretical session on the clinical, ethical, and statutory principles of shared decision-making and ACP; two empirical sessions on conducting ACP conversations in various clinical scenarios using the ConCure-SM booklet through guided role play exercises; and two self-evaluation sessions. The on-site module supports healthcare professionals at the centers on issues concerning the conduction of ACP conversations during the feasibility trial. A web-based trial platform contains the trial case record forms and the self-reported outcome measures [30].

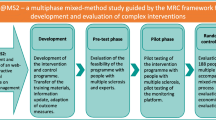

In ConCure-SM project phase 1, we co-produced the ACP booklet. In phase 2, we set up the intervention (which includes the booklet), which is currently being tested for efficacy in the feasibility trial (Fig. 1).

Flow chart of the ConCure-SM project. The two pictures embedded are cover miniatures of the provisional and final booklet. ACP, advance care planning; 4-ACP-E, 4-item ACP Engagement (outcome measure); HP, health professional; MS, multiple sclerosis; NPT, normalization process theory; PwPMS, people with progressive MS; QOC, quality of communication (outcome measure); SO, significant other

The present study refers to project phase 1. Specifically, our objectives were to assess the acceptability and understandability of the ACP booklet for users (PwPMS, significant others, and healthcare professionals) and to refine the booklet accordingly.

Methods

We conducted a multicenter, qualitative study applying the cognitive interview technique with PwPMS and significant others and a focus group meeting with healthcare professionals. We followed the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) (online supplemental file 1).

For PwPMS and significant others, one-to-one cognitive interviews were considered the most appropriate to limit the interview burden and to make it easier for participants to express their feelings. Conceived by cognitive psychologists [31], the cognitive interview technique is traditionally used to evaluate comprehension issues in questionnaire design and to improve self-reported instruments [32]. This technique has also been used to test the understanding of patient information leaflets [33,34,35].

For the healthcare professionals, we chose the focus group to promote interaction and exchange of ideas.

Booklet development

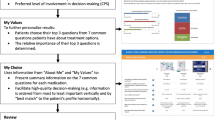

In 2020, an interdisciplinary panel, including an expert patient and a representative of the Italian MS Society, translated and adapted the ACP booklet of the Health Quality & Safety Commission’s New Zealand National ACP Program (online supplemental file 2). The resulting booklet in its provisional version (online supplemental file 3) comprised an introduction, a “guidance,” and the ACP document (the even pages) to be completed electronically or manually by PwPMS together with the referring physician. The introduction explained ACP concepts and advance directives according to the Italian Law 219/2017 and described why ACP is important in MS. Ten fillable sections followed: “My advance care plan,” “What matters to me,” “What worries me,” “Why I’m making an advance care plan,” “How I make decisions,” “If I were no longer able to make decisions: my trustee,” “Thinking about my EOL,” “My treatment and care choices,” “Signatures,” and “Abbreviations.”

Research settings and sampling

The study involved three Italian MS research centers: the Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, Milan; the Azienda USL-IRCCS of Reggio Emilia; and the IRCCS Santa Lucia Foundation, Rome.

PwPMS and significant others aged 18 years or older and fluent in Italian were eligible. PwPMS had to be diagnosed for 1 or more years, able to communicate, and without severe cognitive impairment (clinician’s judgement); they were purposely selected as assorted in age, gender, disability status, age at MS diagnosis, and age at progression. Eligible PwPMS and significant others were invited to participate by neurologists at each participating center. Participants who provided informed consent were contacted by phone or e-mail by an interviewer who provided further details on the study procedures and set a comfortable time for the online interview. PwPMS and significant others were informed that a psychologist dedicated to the study was available (scheduled teleconference or telephone call) in the event negative thoughts or distress arose from reading the booklet or from participation in the interview.

The healthcare professionals were selected following convenience sampling. They were contacted by e-mail among those meeting the following inclusion criteria: physicians, psychologists, nurses, social workers, or physiotherapists with expertise in caring for PwPMS and fluency in Italian.

About 2 weeks before the interviews/focus group, participants received the provisional booklet to familiarize with. Participation was voluntary, and no material incentive was given to study participants.

Data collection

The cognitive interviews and the focus group were held online—to respect COVID-19 restriction measures—between September 2020 and January 2021. All were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

The interviewers (LDP, SV, and AMG) used a pre-planned guide (online supplemental file 4) and prompted PwPMS and significant others to think aloud when answering questions, to explore comprehension and judgments on the ACP booklet items. SV and LDP moderated the focus group using a non-directive style. They asked healthcare professionals to identify unclear or difficult parts/sections and any missing issues. The participants did not know the interviewers and moderators before the study.

Data analysis

We analyzed the cognitive interviews using the framework method [36] according to an inductive approach considered appropriate for making themes emerge and allowing inter-coder agreement. LDP and SV read the transcriptions extensively and wrote comments and initial thoughts in a memo. They coded the text of the first six interviews line by line independently and produced a provisional list of themes as a framework. The themes were discussed with LG. Then, LDP and SV independently reviewed the themes and, through discussions with LG, renamed them if needed and defined subthemes. LDP applied the framework defined from the analysis of the first interviews to the remaining data. She then extracted the most meaningful narratives from the cognitive interviews to draft the final report, which was checked and amended by SV and LG. MP and LG thematically analyzed the focus group transcript by generating codes describing booklet usability from the healthcare professional perspective [37, 38]. The two researchers independently derived themes and subthemes by gathering codes together. After agreeing on the first themes/subthemes, they met the focus group moderators (LDP and SV) and challenged the provisional themes through discussion. Finally, MP and LG reconfigured the themes and subthemes.

As part of the study, two PwPMS and one significant other selected from the most informative, participated in a second round of interviews to validate revisions to the provisional booklet.

Reflexivity

The interviewers, moderators, and analysts were experts in qualitative methods and were supervised by a qualitative methodologist (LG). All authors managed to view the data based on interdisciplinary discussions. Therefore, even if their different backgrounds (LDP and MP are researchers and bioethicists, SV is a palliative care physician, LG is a methodologist trained in education, and AMG is a researcher and a psychologist) may have had a role in suggesting interpretations (interpretation bias), the interdisciplinary work on analysis concurred to bracket personal interests or disciplinary assumptions. The interviewers did not have any existing relationship with the interviewees and were external to the work settings of the healthcare professionals.

Ethical considerations

The ethics committees of each participating center granted formal ethical approvals (Milan, clearance number: 73/2020; Reggio Emilia, clearance number: 2020/0104408; Rome, clearance number: CE/PROG.846). Participants were provided with an information sheet when contacted, and they signed specific, informed consent forms and privacy/confidentiality agreements before data collection.

Results

Cognitive interviews

Eleven PwPMS and three significant others (2 women, 2 spouses, and one daughter) agreed to participate in the study. Of these, seven PwPMS and all the significant others were from Northern Italy. One PwPMS withdrew consent after viewing the booklet, which he experienced as too emotionally engaging. None of the participants requested an interview with the psychologist dedicated to the study.

The median (range) age of the 10 interviewed PwPMS was 54 years (43–71); three were women; median Expanded Disability Status Scale score was 6.0 (4.0–8.5); median age at MS diagnosis was 38 years (21–54); median age at progression was 46 years (35–66).

Following the participants’ request, three interviews (2 with PwPMS and one with SO) were conducted on the telephone; one PwPMS was interviewed in the presence of his spouse. The interviews lasted between 36 and 80 min; 10 were held by LDP, two by SV, and one by AMG.

The interviews provided information related to three themes: booklet’s comprehensibility and clarity, content acceptability and emotional impact, and suggestions for improvement. The main quotations for each identified theme are reported in Table 1.

Comprehensibility and clarity

Participants found the booklet’s title, introduction, and guidance understandable and clear. They reported that the title was consistent with its content and that the guidance embedded in each section was helpful. The examples provided were clear, and the language was plain.

Most participants understood the gradual approach of ACP. However, PwPMS reported that the physician’s role in the ACP process was not openly explained. They also stressed that the booklet needs the presence of a physician to be filled out.

Few PwPMS considered the booklet wordy or redundant.

Content acceptability and emotional impact

Participants, particularly PwPMS, reported that the booklet contents were emotionally demanding; some PwPMS found the description of MS quite difficult and suggested removing the sentence on life expectancy. PwPMS found some pictures, including the cover picture, melancholic, and gloomy. Generally, participants considered the booklet helpful in fostering and improving physician–patient communication, by exploring “the unsaid.”

Suggestions for improvement

Few participants suggested to improve the layout, which was defined as confusing. One PwPMS suggested using abstract pictures with warm colors. Few participants also asked for better explanations of some unfamiliar words and avoiding repetitions.

Focus group

Twelve healthcare professionals (7 neurologists, 3 psychologists, one nurse, and one physiotherapist) participated in the focus group, which lasted 105 min. The analysis identified two main themes: booklet content importance and clarity and challenges to ACP implementation. The main quotations for each theme identified are reported in Table 2.

Content importance and clarity

Healthcare professionals found that the booklet was relevant to clinical practice, even if they never had any direct experience of ACP. They found the booklet too long and its content redundant. Moreover, some of the proposed topics were identified as unclear, while some subjects were not well explained (e.g., palliative sedation, role of the trustee, futile treatments at EOL).

Challenges to ACP implementation

The healthcare professionals found ACP implementation challenging for the difficulty in choosing the right time and their discomfort in talking about EOL issues and choices. For them, the booklet could foster adverse reactions or emotions. Doubts arose about which professional would be responsible for initiating the ACP discussion. Moreover, they convened that patients should use the booklet only together with a healthcare professional. They finally recommended a customized approach to the use of the booklet, tailored to each patient.

Revision of the booklet and second-round cognitive interviews

Based on the qualitative analysis results, we collected the proposed changes (online supplemental file 5) and revised the booklet (online supplemental file 6) accordingly.

We involved two PwPMS and one significant other in the second-round interviews. They confirmed that the revised booklet was improved in clarity of contents and layout. They reported overall satisfaction with the new pictures. However, they reaffirmed the difficulty in facing the booklet topics and the need for a physician when reading out and completing it.

Discussion

This multicenter, qualitative study involved intended users (PwPMS, significant others, and healthcare professionals involved in MS care) in the evaluation and refinement of a booklet to be used during the ACP conversations.

Appraisal of the booklet was crucial for improving its comprehensibility and clarity. Both PwPMS and significant others clearly understood that the booklet described ACP as a process for sharing personal decisions about future care, included EOL care. Still, they reported common misunderstandings about the physician’s role in this process. Moreover, they perceived some concepts as unfamiliar. It is worth mentioning that open EOL conversations through ACP are uncommon in Italy. The Italian Law n. 219/2017 “Provisions for informed consent and advance directives” was approved after a fervent public and political debate lasting almost 20 years. The law identifies paths for the affirmation of patient autonomy and a patient-clinician relationship based on reciprocal trust and respect: the patient’s right to consent to or refuse treatment (article 1); pain therapy, dignity at the EOL, and avoidance of unreasonable treatment obstinacy (article 2); advance directives (article 4); and ACP (article 5). Since the law has entered into force, many initiatives have been promoted to facilitate ACP discussions, but they are not clearly structured, and few studies have been conducted to collect data on ACP use in Italy. We chose the New Zealand “My Advance Care Plan & Guide” (online supplemental file 2) because of its structure and embedded guidance, which helps the patient and the healthcare professional navigate along the ACP process, from the identification of patient values to EOL care choices. This tool is part of a New Zealand Ministry of Health initiative to promote consistency in ACP practice and fulfilment of the 1996 Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights.

Although PwPMS and significant others appraised the booklet as helpful, they focused more on its emotional impact than on its clarity or comprehensibility. Three types of cognitive bias can explain this finding [39,40,41,42]: “Framing bias,” the framing of information (here ACP) which influences the reasoning process; “Projection bias,” when pain, depression, and anger mediate patients’ ability to make consistent treatment choices; and “Present bias,” tending to place excessive weight on the current over the future situation. While the “Framing bias” specifically applies to the present study, where PwPMS and significant others were asked to examine a booklet out of the context for which it is intended to be used (i.e., the ACP process), the other two biases also pertain to the ConCure-SM feasibility trial and were addressed in the trial protocol [30]. Considering the “Present bias,” the training program which is part of the trial specifically focuses on priming neurologists and other healthcare professionals in discussing with patients their future goals of care, including the EOL phase. Considering the “Projection bias,” since a study-related increase in emotional burden cannot be ruled out, PwPMS mood symptoms, assessed through the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, are being recorded at baseline and during follow-up. The independent Data and Safety Monitoring Committee monitors this safety outcome as well as the occurrence of any serious adverse event (admission to psychiatric ward, suicide attempt, death) [30].

Consistently with the most recent literature, healthcare professionals highlighted the common barriers to ACP implementation: hesitance to discuss EOL with patients, fear of causing them distress and loss of hope, lack of knowledge and self-confidence in ACP conversations, and time/space constraints [1, 20,21,22, 43, 44]. A scoping review on ACP interventions in neurodegenerative disorders found a total of 10 randomized controlled studies, all conducted in the dementia setting [25]. A recently published pilot trial on a nurse-led interview to promote ACP in patients with early dementia showed that the intervention was well received by patients and their significant others. Participants expressed satisfaction with the procedure, especially regarding the opportunity to discuss a sensitive topic with the help of a facilitator [45]. However, only 16 patients were enrolled out of 105 screened; the trial revealed misconceptions about dementia and ACP in patients, significant others, and healthcare professionals, as well as structural and institutional challenges. The authors concluded that “a large scale trial to test a dementia-specific tool of ACP is currently not feasible in Western Switzerland and should be endorsed in a systemic approach of ACP” [45].

Healthcare professionals identified the long trajectory of MS as an additional challenge, with the risk of anticipating too much ACP discussion or deferring to a stage when it is not possible anymore due to patients’ loss of their deliberation capacity. These findings point out the need for training neurologists and other MS healthcare professionals in ACP.

This study has some limitations. Although the cognitive interviews were the most appropriate approach, the topic was challenging, and the interviews often shifted from the cognitive appraisal of the booklet to its emotional impact. Second, data saturation was not discussed (online supplemental file 1). Finally, our findings are specific to the Italian context, and few participants were women; thus, transferability may be limited.

Conclusions

Acknowledging that our ultimate goal is to provide evidence on the effectiveness of the ConCure-SM intervention, we believe that the present results provide new knowledge on the co-production of an MS-specific ACP intervention and on the challenges envisaged to ACP implementation in Italy.

Data availability

Interview and focus group quotations are available in the manuscript, and the interview and focus group guides are provided within the manuscript’s supporting information. Interviews and focus group meeting transcripts cannot be made publicly available as study participants consented to participate with the understanding that their data would remain anonymous and confidential. Further excerpts of the study data are available on request from the Ethics Committee of Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, Milan (institutional contact: comitatoetico@istituto-besta.it).

Code availability

See “Data availability”.

References

Walton C, King R, Rechtman L, Kaye W, Leray E, Marrie RA, Robertson N, La Rocca N, Uitdehaag B, van der Mei I, Wallin M, Helme A, Angood Napier C, Rijke N, Baneke P (2020) Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: insights from the Atlas of MS, third edition. Mult Scler 26:1816–1821. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458520970841

Reich DS, Lucchinetti CF, Calabresi PA (2018) Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 378:169–180. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1401483

Filippi M, Bar-Or A, Piehl F, Preziosa P, Solari A, Vukusic S, Rocca MA (2018) Multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 4:43. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-018-0041-4

Kingwell E, van der Kop M, Zhao Y, Shirani A, Zhu F, Oger J, Tremlett H (2012) Relative mortality and survival in multiple sclerosis: findings from British Columbia, Canada. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 83:61–66. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2011-300616

Scalfari A, Knappertz V, Cutter G, Goodin DS, Ashton R, Ebers GC (2013) Mortality in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology 81:184–192. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829a3388

Lunde HMB, Assmus J, Myhr KM, Bø L, Grytten N (2017) Survival and cause of death in multiple sclerosis: a 60-year longitudinal population study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 88:621–625. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2016-315238

Chiaravalloti ND, DeLuca J (2008) Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 7:1139–1151. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70259-X

Higginson IJ, Hart S, Silber E, Burman R, Edmonds P (2006) Symptom prevalence and severity in people severely affected by multiple sclerosis. J Palliat Care 22:158–165

Hirst C, Swingler R, Compston DA, Ben-Shlomo Y, Robertson NP (2008) Survival and cause of death in multiple sclerosis: a prospective population-based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 79:1016–1021. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2007.127332

Sumelahti ML, Hakama M, Elovaara I, Pukkala E (2010) Causes of death among patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 16:1437–1442. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458510379244

Giordano A, Ferrari G, Radice D, Randi G, Bisanti L, Solari A, POSMOS study, (2012) Health-related quality of life and depressive symptoms in significant others of people with multiple sclerosis: a community study. Eur J Neurol 19:847–854. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03638.x

Forte DN, Kawai F, Cohen C (2018) A bioethical framework to guide the decision-making process in the care of seriously ill patients. BMC Med Ethics 19:78. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-018-0317-y

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guidelines (2021). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng197/resources/shared-decision-making-pdf-66142087186885. Accessed 15 July 2023

Rietjens JAC, Sudore RL, Connolly M, van Delden JJ, Drickamer MA, Droger M, van der Heide A, Heyland DK, Houttekier D, Janssen DJA, Orsi L, Payne S, Seymour J, Jox RJ, Korfage IJ, European Association for Palliative Care (2017) Definition and recommendations for advance care planning: an international consensus supported by the European Association for Palliative Care. Lancet Oncol 18:e543–e551. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30582-X

Hickman SE, Lum HD, Walling AM, Savoy A, Sudore RL (2023) The care planning umbrella: the evolution of advance care planning. J Am Geriatr Soc 71:2350–2356. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.18287

Prince-Paul M, DiFranco E (2017) Upstreaming and normalizing advance care planning conversations—a public health approach. Behav Sci 7:18. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7020018

Rietjens J, Korfage I, Taubert M (2021) Advance care planning: the future. BMJ Support Palliat Care 11:89–91. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002304

Koffler S, Mintzker Y, Shai A (2020) Association between palliative care and the rate of advanced care planning: a systematic review. Palliat Support Care 18:589–601. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951519001068

Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Rietjens JA, van der Heide A (2014) The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med 28:1000–1025. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216314526272

Bernard C, Tan A, Slaven M, Elston D, Heyland DK, Howard M (2020) Exploring patient-reported barriers to advance care planning in family practice. BMC Fam Pract 21:94. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-020-01167-0

Tokunaga-Nakawatase Y, Ochiai R, Sanjo M, Tsuchihashi-Makaya M, Miyashita M, Ishikawa T, Watabe S (2020) Perceptions of physicians and nurses concerning advanced care planning for patients with heart failure in Japan. Ann Palliat Med 9:1718–1731. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm-19-685

Herreros B, Benito M, Gella P, Valenti E, Sánchez B, Velasco T (2020) Why have advance directives failed in Spain? BMC Med Ethics 21:113. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-020-00557-4

Solari A, Giordano A, Sastre-Garriga J, Köpke S, Rahn AC, Kleiter I, Aleksovska K, Battaglia MA, Bay J, Copetti M, Drulovic J, Kooij L, Mens J, Meza Murillo ER, Milanov I, Milo R, Pekmezovic T, Vosburgh J, Silber E, Veronese S, EAN guideline task force (2020) EAN guideline on palliative care of people with severe, progressive multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol 27:1510–1529. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.14248

Solari A, Giordano A, Sastre-Garriga J, Köpke S, Rahn AC, Kleiter I, Aleksovska K, Battaglia MA, Bay J, Copetti M, Drulovic J, Kooij L, Mens J, Murillo ERM, Milanov I, Milo R, Pekmezovic T, Vosburgh J, Silber E, Veronese S, Patti F, Voltz R, Oliver DJ (2020) EAN guideline on palliative care of people with severe, progressive multiple sclerosis. J Palliat Med 23:1426–1443. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2020.0220

Giordano A, De Panfilis L, Perin M, Servidio L, Cascioli M, Grasso MG, Lugaresi A, Pucci E, Veronese S, Solari A (2022) Advance care planning in neurodegenerative disorders: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19:803. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020803

Strupp J, Hartwig A, Golla H, Galushko M, Pfaff H, Voltz R (2012) Feeling severely affected by multiple sclerosis: what does this mean? Palliat Med 26:1001–1010. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216311425420

Edmonds P, Vivat B, Burman R, Silber E, Higginson IJ (2007) Loss and change: experiences of people severely affected by multiple sclerosis. Palliat Med 21:101–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216307076333

Cottrell L, Economos G, Evans C, Silber E, Burman R, Nicholas R, Farsides B, Ashford S, Koffman JS (2020) A realist review of advance care planning for people with multiple sclerosis and their families. PLoS ONE 15:e0240815. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240815

Koffman J, Penfold C, Cottrell L, Farsides B, Evans CJ, Burman R, Nicholas R, Ashford S, Silber E (2022) “I wanna live and not think about the future” what place for advance care planning for people living with severe multiple sclerosis and their families? A qualitative study. PloS One 17:e0265861. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265861

De Panfilis L, Veronese S, Bruzzone M, Cascioli M, Gajofatto A, Grasso MG, Kruger P, Lugaresi A, Manson L, Montepietra S, Patti F, Pucci E, Solaro C, Giordano A, Solari A (2021) Study protocol on advance care planning in multiple sclerosis (ConCure-SM): intervention construction and multicentre feasibility trial. BMJ Open 11:e052012. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052012

Jobe JB (2003) Cognitive psychology and self-reports: models and methods. Qual Life Res 12:219–227. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1023279029852

Murtagh FE, Addington-Hall JM, Higginson IJ (2007) The value of cognitive interviewing techniques in palliative care research. Palliat Med 21:87–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216306075367

Lake AA, Speed C, Brookes A, Heaven B, Adamson AJ, Moynihan P, Corbett S, McColl E (2007) Development of a series of patient information leaflets for constipation using a range of cognitive interview techniques: LIFELAX. BMC Health Serv Res 7:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-7-3

Okan Y, Petrova D, Smith SG, Lesic V, Bruine de Bruin W (2019) How do women interpret the NHS information leaflet about cervical cancer screening? Med Decis Making 39:738–754. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X19873647

Smith SG, Vart G, Wolf MS, Obichere A, Baker HJ, Raine R, Wardle J, von Wagner C (2015) How do people interpret information about colorectal cancer screening: observations from a think-aloud study. Health Expect 18:703–714. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12117

Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S (2013) Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 13:117. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

Braun V, Clarke V (2021) Thematic analysis. A practical guide. Sage, London

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3:77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Samuelson W, Zeckhauser R (1988) Status quo bias in decision making. J Risk Uncertain 1:7–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00055564

Ozdemir S, Finkelstein EA (2018) Cognitive bias: the downside of shared decision making. JCO Clin Cancer Inform 2:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1200/CCI.18.00011

Quoidbach J, Gilbert DT, Wilson TD (2013) The end of history illusion. Science 339(6115):96–98. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1229294

Chochinov HM, Tataryn D, Clinch JJ, Dudgeon D (1999) Will to live in the terminally ill. Lancet 354(9181):816–819. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(99)80011-7

De Panfilis L, Rossi PG, Mazzini E, Pistolesi L, Ghirotto L, Noto A, Cuocolo S, Costantini M (2020) Knowledge, opinion, and attitude about the Italian Law on advance directives: a population-based survey. J Pain Symptom Manage 60:906-914.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.06.020

Lankarani-Fard A, Knapp H, Lorenz KA, Golden JF, Taylor A, Feld JE, Shugarman LR, Malloy D, Menkin ES, Asch SM (2010) Feasibility of discussing end-of-life care goals with inpatients using a structured, conversational approach: the go wish card game. J Pain Symptom Manage 39:637–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.08.011

Bosisio F, Sterie A, RubliTruchard E, Jox RJ (2021) Implementing advance care planning in early dementia care: results and insights from a pilot interventional trial. BMC Geriatr 21:573. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02529-8

Acknowledgements

This work was promoted by the “Gruppo di studio Bioetica e Cure Palliative” of the Italian Neurological Society (SIN). We would like to thank the PwPMS and their significant others, to whom this research is dedicated. The funding sources played no role in the study design and played no role in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

COLLABORATORS

ConCure-SM project investigators

Lead by A. Solari, Milan (alessandra.solari@istituto-besta.it).

Steering Committee: M. Cascioli, L. De Panfilis, M. G. Grasso, A. Giordano, A. Lugaresi, E. Pucci, A. Solari, C. Solaro, S. Veronese, M. Bruzzone, P. Kruger, A. Gajofatto (University of Verona), F. Patti (University Hospital Policlinico Vittorio Emanuele, Catania).

Data Safety and Monitoring Committee: K. Brazil (School of Nursing and Midwifery, Queen’s University of Belfast, Belfast, Northern Ireland, UK), B. Farsides (Brighton & Sussex Medical School, Falmer, Brighton, UK), L. Orsi (The Italian Society of Palliative Care (SICP), Milan, Italy, C. Peruselli (SICP, Milan, Italy), and D. Oliver (The Tizard Centre, University of Kent, Canterbury, UK) (Chair).

Data Management and Analysis Committee: M. Farinotti (data manager) and A. Giordano.

Qualitative Analysis Panel: M. Cascioli, L. De Panfilis, L. Ghirotto, K. Mattarozzi (Department of Experimental, Diagnostic and Specialistic Medicine, School of Medicine, Alma Mater Studiorum University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy), M. Perin, and S. Veronese.

Healthcare Professional Training Panel: M. Cascioli, L. De Panfilis, K. Mattarozzi, E. Pucci, M. Rimondini (Section of Clinical Psychology, Department of Neuroscience, Biomedicine and Movement Sciences, University of Verona, Policlinico G.B. Rossi, Verona, Italy), A. Solari, and S. Veronese.

Linguistic Validation Panel: M. Farinotti, A. Giordano, P. Kruger, A. Solari, S. Veronese, and three independent translators.

Enrolling Centers: Department of Neuroscience, Biomedicine and Movement Sciences, University of Verona; Unit of Neurology, Borgo Roma Hospital, Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Integrata Verona: A. Gajofatto, A. Filosa, R. Orlandi; Department of Rehabilitation, CRRF “Mons. L. Novarese,” Moncrivello (VC): C. Solaro, E. Grange; Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia: L. De Panfilis, S. Montepietra, F. Sireci; UOSI Riabilitazione Sclerosi Multipla, IRCCS Istituto delle Scienze Neurologiche di Bologna; Dipartimento di Scienze Biomediche e Neuromotorie, Università di Bologna, Bologna: A. Lugaresi, L. Sabbatini, C. Scandellari, E. Ferriani; IRCCS Santa Lucia Foundation, Rome: M.G. Grasso, G. Presicce; University Hospital Policlinico Vittorio Emanuele, Catania: F. Patti, C.G. Chisari, S. Toscano.

Funding

We thank the Italian Ministry of Health (RRC) and the “Associazione marchigiana sclerosi multipla e altre malattie neurologiche ODV-ETS” for their support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LDP, SV, LG, and AS contributed to study conception, design, and protocol development. LDP, SV, LG, MP, MF, MGG, PK, LM, AL, AMG, EP, CS, and AS were involved in data collection and analysis. AG, LDP, and AS drafted the manuscript. AG, LDP, SV, MB, MC, MF, AMG, MGG, PK, AL, LM, MP, EP, CS, LG, and AS approved the final submitted manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The ethics committees of each participating center granted formal ethical approvals (Milan, clearance number 73/2020; Reggio Emilia, clearance number 2020/0104408; Rome, clearance number CE/PROG.846).

Consent to participate

Participants were provided with an information sheet when contacted, and they signed specific, informed consent forms and privacy/confidentiality agreements before data collection.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Giordano, A., De Panfilis, L., Veronese, S. et al. User appraisal of a booklet for advance care planning in multiple sclerosis: a multicenter, qualitative Italian study. Neurol Sci 45, 1145–1154 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-023-07087-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-023-07087-y