Abstract

In addition to headache, migraine is characterized by a series of symptoms that negatively affects the quality of life of patients. Generally, these are represented by nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia and osmophobia, with a cumulative percentage of the onset in about 90% of the patients. From this point of view, menstrually related migraine—a particularly difficult-to-treat form of primary headache—is no different from other forms of migraine. Symptomatic treatment should therefore be evaluated not only in terms of headache relief, but also by considering its effect on these migraine-associated symptoms (MAS). Starting from the data collected in a recently completed multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study with almotriptan in menstrually related migraine, an analysis of the effect of this drug on the evolution of MAS was performed. Data suggest that almotriptan shows excellent efficacy on MAS in comparison to the placebo, with a significant reduction in the percentages of suffering patients over a 2-h period of time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Migraine is much more than just headache since it is characterized by a series of symptoms that are often particularly severe and disturbing for the patients and which greatly contribute to worsening their quality of life. The most common migraine-associated symptoms (MAS) are nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia and osmophobia, with a cumulative percentage of the onset in about 90% of the patients.

In menstrually related migraine (MRM), a particularly difficult-to-treat form of primary headache, MAS are also present in percentages similar to the other forms of migraine (non-MRM). Data in recent literature report that in MRM versus non-MRM, pre-treatment nausea is present in 40.4 versus 33.4% of attacks, phonophobia in 71.3 versus 75.4% of attacks and photophobia in 84.0 versus 78.9% of attacks, respectively [1].

MRM is a common form of migraine affecting more than 50% of female migraineurs [2]. Population-based studies indicate that this type of migraine, which occurs during the perimenstrual period, is mostly migraine without aura and is significantly more likely (but not exclusively) to occur on the 2 days before and on the first 3 days of menses. Only a small percentage of female migraineurs (7–12%) have migraine attacks exclusively occurring in this period, a condition known as “pure menstrual migraine”.

The various drugs used to treat ‘ordinary’ migraine may be prescribed for MRM, but triptans—selective 5-hydroxytriptamine (5-HT) 1B/1D receptor agonists, which are considered the most effective specific acute anti-migraine medications—are preferable for MRM in view of its difficult-to-treat nature [2, 3].

Almotriptan is one of the most recent selective 5-HT 1B/1D receptor agonists successfully used for the acute treatment of migraine. It is rapidly absorbed, with very good oral bioavailability (80%), and at the usual dose of 12.5 mg is at least as or even more effective than sumatriptan 100 mg and has a significantly better tolerability profile [4].

A placebo-controlled randomized study with almotriptan in MRM was recently concluded and data relevant to the number of patients reporting MAS were therefore available for a separate analysis. It is interesting to evaluate the effects of the symptomatic treatment of the migraine attack more closely, not only as far as pain relief is concerned, but also in terms of MAS evolution, particularly if patients are suffering from MRM.

The aim of this analysis is to show and discuss the evolution of nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia and osmophobia in MRM patients following treatment with almotriptan 12.5 mg or placebo.

Methods

The original trial was a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study that was followed by an open phase. In the double-blind period, two single menstrual migraine attacks per menstrual cycle were treated with almotriptan or placebo (and vice versa). In the open phase, two additional single attacks (3rd and 4th) per menstrual cycle were treated with almotriptan.

The primary objective of the original study consisted in proving the effectiveness (superiority hypothesis) of almotriptan versus placebo by testing the percentages of patients pain free at 2 h (primary study end point) following drug intake.

Patients were provided with a diary card to record their migraine attacks for each menstrual cycle under consideration. In particular, at 0, 15, 30, 60, 120 min and 24 h after drug intake, the presence or absence of nausea, vomiting, phonophobia, photophobia and osmophobia were recorded along with the intensity of headache pain and other parameters.

Treatment

Almotriptan or matching placebo was self-administered at the onset of the first menstrual migraine attack occurring during the specified window (day −2 to +3) of the menstrual cycle. One single menstrual migraine attack per menstrual cycle was treated in four different menstrual cycles. One out of the first two of the four attacks was placebo-treated. Each attack was treated with one single tablet.

Statistical analysis

For each symptom and for each scheduled time, the percentage of patients was analyzed using a generalized linear model implemented with binomial distribution, log-link function and generalized estimating equations (GEE). Results were reported as risk ratio (RR) with associated 95% CL and two-tailed p values. The main analysis was performed on the modified intention-to-treat population (mITT), defined as all randomized patients who received at least one dose of study medication and in whom the evaluation of the primary outcome, at both the first and the second period of the double-blind phase, was available.

Results

Following a screening period, 147 outpatient women aged 18–50 and suffering from MRM without aura (IHS criteria) were randomized: 74 to almotriptan-placebo and 73 to placebo-almotriptan; 122 patients completed the double-blind phase (mITT) and 105 completed the additional open follow-up phase (two further attacks).

Patient disposition is summarized in Table 1.

All patients were Caucasian and no statistically significant differences were found when comparing age, height and weight (Table 2).

In general, descriptive statistics highlighted that: (a) about half of the migraine attacks occurred between the first and second day of the menstrual period, (b) moderate/severe headache occurred in 55–60% of migraine attacks and (c) an association with other symptoms (nausea, vomiting, etc.) was present in about 90% of patients. Around 30% of the patients were able to treat migraine attack during its mild phase.

The study achieved its main objective of demonstrating the superiority of almotriptan compared to placebo in terms of percentage of patients being pain free at 2 h. Furthermore, almotriptan was well-tolerated, with few adverse events compared to placebo.

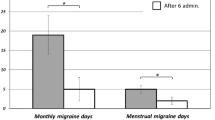

The results on MAS appear to be consistent with the migraine pain scale results, with sparse statistically significant differences in favor of almotriptan (Fig. 1a–e). The principal findings are summarized below.

Nausea

Double-blind phase

The percentages of patients that experienced nausea varied, respectively, from 43.4% (almotriptan) and 41% (placebo) at 15 min with a RR of 1.04 (95% CI; 0.86–1.27; p value = 0.6609) to 19% (almotriptan) and 36.7% (placebo) at 2 h with a RR of 0.52 (95% CI; 0.36–0.76; p value = 0.0007) and to 10.1% (almotriptan) and 19.1% (placebo) at 24 h with a RR of 0.52 (95% CI; 0.28–0.96; p value = 0.0354).

Follow-up phase

The percentages of patients that experienced nausea varied, respectively, from 41.8% (attack no. 3) and 36.2% (attack no. 4) at 15 min to 14.5% (attack no. 3) and 14.4% (attack no. 4) at 2 h and to 10.5% (attack no. 3) and 11.9% (attack no. 4) at 24 h.

Vomiting

Double-blind phase

The percentages of patients that experienced vomiting varied, respectively, from 3.3% (almotriptan) and 4.9% (placebo) at 15 min with a RR of 0.58 (95% CI; 0.16–2.13; p value = 0.4100) to 4.1% (almotriptan) and 9.2% (placebo) at 2 h with a RR of 0.44 (95% CI; 0.18–1.13; p value = 0.0876) and to 2.5% (almotriptan) and 0.9% (placebo) at 24 h with a RR not estimated.

Follow-up phase

The percentages of patients that experienced vomiting varied, respectively, from 6.4% (attack no. 3) and 1.9% (attack no. 4) at 15 min to 2.7% (attack no. 3) and 1% (attack no. 4) at 2 h and to 1% (attack no. 3) and 0% (attack no. 4) at 24 h.

Photophobia

Double-blind phase

The percentages of patients that experienced photophobia varied, respectively, from 58.2% (almotriptan) and 60.7% (placebo) at 15 min with a RR of 0.96 (95% CI; 0.83–1.10; p value = 0.5421) to 33.1% (almotriptan) and 49.2% (placebo) at 2 h with a RR of 0.67 (95% CI; 0.50–0.90; p value = 0.0083) and to 10.9% (almotriptan) and 22.6% (placebo) at 24 h with a RR of 0.42 (95% CI; 0.21–0.80; p value = 0.0092).

Follow-up phase

The percentages of patients that experienced photophobia varied, respectively, from 60% (attack no. 3) and 59% (attack no. 4) at 15 min to 24.5% (attack no. 3) and 21.2% (attack no. 4) at 2 h and to 12.4% (attack no. 3) and 15.8% (attack no. 4) at 24 h.

Phonophobia

Double-blind phase

The percentages of patients that experienced phonophobia varied, respectively, from 59% (almotriptan) and 54.9% (placebo) at 15 min with a RR of 1.07 (95% CI; 0.93–1.24; p value = 0.3288) to 30.6% (almotriptan) and 41.7% (placebo) at 2 h with a RR of 0.73 (95% CI; 0.53–1.01; p value = 0.0566) and to 10.1% (almotriptan) and 18.3% (placebo) at 24 h with a RR of 0.48 (95% CI; 0.24–0.95; p value = 0.0347).

Follow-up phase

The percentages of patients that experienced phonophobia varied, respectively, from 50% (attack no. 3) and 48.6% (attack no. 4) at 15 min to 18.2% (attack no. 3) and 20.2% (attack no. 4) at 2 h and to 11.4% (attack no. 3) and 13.9% (attack no. 4) at 24 h.

Osmophobia

Double-blind phase

The percentages of patients that experienced osmophobia varied, respectively, from 20.5% (almotriptan) and 15.6% (placebo) at 15 min with a RR of 1.32 (95% CI; 0.92–1.89; p value = 0.1375) to 12.4% (almotriptan) and 12.5% (placebo) at 2 h with a RR of 0.99 (95% CI; 0.55–1.81; p value = 0.9856) and to 4.2% (almotriptan) and 6.1% (placebo) at 24 h with a RR of 0.62 (95% CI; 0.19–2.05; p value = 0.4340).

Follow-up phase

The percentages of patients that experienced osmophobia varied, respectively, from 15.5% (attack no. 3) and 12.4% (attack no. 4) at 15 min to 1.8% (attack no. 3) and 3.8% (attack no. 4) at 2 h and to 4.8% (attack no. 3) and 4% (attack no. 4) at 24 h.

Conclusions

MRM is particularly difficult to treat and the presence of associated symptoms significantly worsens patient functioning. This is also highlighted by the correlation found between the severity of MAS (especially nausea, photophobia and phonophobia) and impaired functioning. In fact, quality of life is critically lowered by the presence of severe MAS, and consequently symptomatic treatment should also be carefully evaluated in terms of its efficacy in affecting MAS.

Almotriptan has proven to be effective in the control of migraine pain in menstrual migraine [5]. The present study demonstrated that almotriptan in MRM treatment showed excellent efficacy on MAS in comparison to placebo, with a significant reduction in the percentages of suffering patients over a 2-h period of time. These positive data were also confirmed during the open follow-up phase.

References

Diamond ML, Cady RK, Mao L, Biondi DM, Finlayson G, Greenberg SJ, Wright P (2008) Characteristics of migraine attacks and responses to almotriptan treatment: a comparison of menstrually related and nonmenstrually related migraines. Headache 48:248–258

Granella F, Sances G, Allais G, Nappi R, Tirelli A, Benedetto C, Brundu B, Facchinetti F, Nappi G (2004) Characteristics of menstrual and nonmenstrual attacks in women with menstrually related migraine referred to headache centres. Cephalalgia 24:707–716

Allais G, Castagnoli Gabellari I, De Lorenzo C, Mana O, Benedetto C (2007) Menstrual migraine: clinical and therapeutical aspects. Expert Rev Neurother 7(9):1105–1120

Dowson AJ, Massiou H, Laynex JM, Cabarrocas X (2002) Almotriptan is an effective and well tolerated treatment for migraine pain: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled clinical trial. Cephalalgia 22:453–461

Allais G, Acuto G, Cabarrocas X, Esbri R, Benedetto C, Bussone G (2006) Efficacy and tolerability of almotriptan versus zolmitriptan for the acute treatment of menstrual migraine. Neurol Sci 27(Suppl 2):S193–S197

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Almirall SA, Spain.

Conflict of interest statement

G. Acuto is an employee of Almirall SpA, Italy. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest related to the publication of this article.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Allais, G., Acuto, G., Benedetto, C. et al. Evolution of migraine-associated symptoms in menstrually related migraine following symptomatic treatment with almotriptan. Neurol Sci 31 (Suppl 1), 115–119 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-010-0302-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-010-0302-9