Abstract

Objective

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in biologic-naïve rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients with high disease activity and inadequate response/intolerance to methotrexate have shown interleukin-6 (IL-6) receptor inhibitors (IL-6Ri) to be superior to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) as monotherapy. This observational study aimed to compare the effectiveness of TNFi vs IL-6Ri as mono- or combination therapy in biologic/targeted synthetic (b/ts) -experienced RA patients with moderate/high disease activity.

Methods

Eligible b/ts-experienced patients from the CorEvitas RA registry were categorized as TNFi and IL-6Ri initiators, with subgroups initiating as mono- or combination therapy. Mixed-effects regression models evaluated the impact of treatment on Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI), patient-reported outcomes, and disproportionate pain (DP). Unadjusted and covariate-adjusted effects were reported.

Results

Patients initiating IL-6Ri (n = 286) vs TNFi monotherapy (n = 737) were older, had a longer RA history and higher baseline CDAI, and were more likely to initiate as third-line therapy; IL-6Ri (n = 401) vs TNFi (n = 1315) combination therapy initiators had higher baseline CDAI and were more likely to initiate as third-line therapy. No significant differences were noted in the outcomes between TNFi and IL-6Ri initiators (as mono- or combination therapy).

Conclusion

This observational study showed no significant differences in outcomes among b/ts-experienced TNFi vs IL-6Ri initiators, as either mono- or combination therapy. These findings were in contrast with the previous RCTs in biologic-naïve patients and could be explained by the differences in the patient characteristics included in this study. Further studies are needed to help understand the reasons for this discrepancy in the real-world b/ts-experienced population.

Key Points • Patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) often require switching between biologics or targeted synthetic (b/ts) disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) to achieve their treatment target. • Head-to-head randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in biologic-naïve RA patients with high disease activity and inadequate response/intolerance to methotrexate have shown interleukin-6 receptor inhibitors (IL-6Ri) to be superior to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) as monotherapy; however, there are no RCTs comparing these therapies in a population previously treated with b/tsDMARDs (i.e., b/ts-experienced patients). • This observational study compared the effectiveness of TNFi vs IL-6Ri (as mono- or combination therapy) in b/ts-experienced RA patients with moderate or high disease activity and found no significant differences in clinical outcomes for the two treatments. • A discrepancy is noted between our study and RCTs, which have shown superiority of IL-6Ri therapy (albeit in biologic-naïve patients). Further analyses may help elucidate the reason for this discrepancy in the real-world b/ts-experienced population. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a global public health challenge, with increasing rates of age-standardized point prevalence and annual incidence [1]. If inadequately treated, RA may cause joint damage, disability, and other sequelae that impact the quality of life and lead to economic losses [2]. Early diagnosis and treatment are important to reduce this disease burden in patients with RA, and a treat-to-target (TTT) approach is recommended to achieve clinical remission or low disease activity (LDA). Over the years, this has become a realistic goal with the advent of effective medications, including conventional synthetic (cs), biologic (b), and targeted synthetic (ts) disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) [3, 4].

At present, methotrexate (MTX), a csDMARD is considered an integral part of the first-line treatment strategy in patients with RA [3]. Further optimization of MTX dosage or addition of b/tsDMARDs is driven by the TTT approach. If a b/tsDMARD fails, switching to a b/tsDMARD of a different class is recommended to achieve the target; however, there are limited data to support the choice of drug class for this approach [3, 4].

Two of the currently approved b/tsDMARD therapy classes act via inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF) or interleukin-6 receptor (IL-6R), thereby playing a vital role in RA via their anti-inflammatory effects [5, 6]. Although 10% to 50% of RA patients achieve remission in 6 to 12 months with the use of the first b/tsDMARD (such as TNF inhibitor [TNFi] or IL-6R inhibitor [IL-6Ri]), either as monotherapy or in combination with csDMARDs, a meaningful proportion of patients have active disease and progression of disability [7, 8]. Thus, patients require switching between b/tsDMARDs to achieve the target of remission [3, 4], and this decision can be informed by research on the comparative effectiveness of these therapies.

A randomized Phase 3 head-to-head (H2H) trial (MONARCH) in biologic-naïve RA patients, with high disease activity and intolerance or inadequate response to MTX, showed sarilumab (an IL-6Ri) monotherapy to be superior to adalimumab (a TNFi) monotherapy for reducing disease activity and signs/symptoms of RA [9]. Tocilizumab (another IL-6Ri) also demonstrated superior clinical response than adalimumab in a Phase 4 randomized controlled trial (RCT) as monotherapy in a similar population [10]. However, there is limited research comparing the relative effectiveness of TNFi vs IL-6Ri as monotherapy or in combination with csDMARDs in RA patients with moderate or high disease activity, who have previously been treated with b/tsDMARDs (i.e., b/ts-experienced patients), in a real-world patient population.

The CorEvitas RA registry (formerly known as Corrona) is a prospective, multicenter, real-world registry, launched in the United States (US), and collects data (at the time of a clinical encounter) of clinical outcomes and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) from both physicians and patients. At present, the registry includes information on > 56,000 patients with RA from 857 rheumatologists across 42 states in the US [11]. Based on the CorEvitas RA registry, a retrospective examination of prospectively collected data was conducted to assess the clinical outcomes in b/ts-experienced RA patients, who received TNFi or IL-6Ri as monotherapy or in combination with csDMARDs. The objective of the study was to compare the effectiveness of second- and third-line TNFi vs IL-6Ri (as mono- or combination therapy) in treating RA patients with moderate or high disease activity.

Materials and methods

Study design and patient population

This was a retrospective, observational study in which data from adult RA patients, within the US CorEvitas RA registry [11], were evaluated. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all participating investigators obtained full ethics or institutional review board (IRB) approval (central IRB: New England Independent Review Board [NEIRB] number: 120160610 and/or individual approvals at sites). All registry patients were required to provide written informed consent prior to participation.

Adult patients with RA (≥ 18 years) who initiated a TNFi (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, or infliximab) or IL-6Ri (sarilumab or tocilizumab) during or after January 2010 (until May 2020) were included. The study period was selected based on the approval and clinical availability of IL-6Ri and TNFi classes of therapeutics. Patients were included in the study if they had a history of one or two b/tsDMARDs prior to initiation, moderate (Clinical Disease Activity Index [CDAI]: 10 to ≤ 22) or high (CDAI: > 22) disease activity at initiation [12], and recorded a follow-up visit at 6 (± 3) months after therapy initiation. Patients who were not eligible to participate in the registry included those who: (i) had a diagnosis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, spondylarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, or any other form of autoimmune inflammatory arthritis; (ii) were only on csDMARDs; or (iii) were participating/planning to participate in any RA clinical trial.

Study treatments

All RA patients with moderate or high disease activity were categorized as either TNFi or IL-6Ri initiators, both with subgroups initiating as monotherapy or combination therapy. Monotherapy initiators stopped the prior csDMARDs at the time of initiating TNFi or IL-6Ri or anytime earlier, and combination therapy initiators received MTX with or without other csDMARDs, in addition to TNFi or IL-6Ri.

Study assessments

At the baseline visit (i.e., visit at which TNFi/IL-6Ri was started), the following variables were recorded for each patient: demographic characteristics, lifestyle status, history of comorbidities, medication use, and disease severity measures including the CDAI and PROs. Clinical outcomes collected were as follows:

Clinical disease activity index

Mean change and achievement of low disease activity (LDA; CDAI: ≤ 10); achievement of minimal clinically important difference (MCID, i.e., improvement by ≥ 6 [for moderate disease activity at baseline] or ≥ 12 [for high disease activity at baseline] units) in the CDAI from baseline to follow-up; and achievement of remission (CDAI: ≤ 2.8) [12, 13].

Patient-reported outcomes

Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index (HAQ-DI) (mean change and achievement of improvement in the HAQ-DI of ≥ 0.22 or ≥ 0.30 units) [14, 15]; EuroQol-5 Dimension (EQ-5D) score (mean change); pain visual analog scale (VAS, 0–100) (mean change and achievement of improvement by ≥ 10 units); patient global assessment (VAS, 0–100) (mean change and achievement of improvement by ≥ 10 units) [16]; and fatigue (single-item VAS, 0–100) (mean change and achievement of improvement by ≥ 10 units) [17].

Disproportionate pain (DP) [18, 19]

Presence or absence of DP1 at 6 months among patients with DP1 at baseline; and presence or absence of DP2 at 6 months among patients with DP2 at baseline, for which:

Presence of DP1 is defined as:

Presence of DP2 (among those with TJC > 0) is defined as:

where, TJC is 28-tender joint count and SJC is 28-swollen joint count.

The following outcomes were measured as exploratory analyses: response to prior TNFi therapies (using duration of previous TNFi) to investigate whether response/non-response to prior TNFi therapy channeled patients to different subsequent treatments (TNFi vs IL-6Ri). Also, change in the prednisone dose from baseline to 6 months (using baseline dose of prednisone) was evaluated for all patients.

No safety outcomes were assessed in the present study.

Statistical analyses

Both TNFi and IL-6Ri initiators (as mono- or combination therapy) were compared at baseline and at the follow-up visit. Descriptive statistics were measured for each variable at baseline. Continuous variables were summarized using mean and standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables were reported as total number and proportion of each category. Univariate comparisons between therapy groups were performed using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables.

Since the same patient can potentially contribute to multiple observations for repeated initiations within the same drug class or across different drug classes, mixed-effects regression models with random intercept for patient were used to account for the potential correlation among separate observations from the same patient.

For mean change in outcomes, the difference from baseline to six-month follow-up was calculated for each patient and used as the dependent variable in mixed-effect linear regression models. For binary outcomes, an indicator variable was created, measuring whether a patient achieved the outcome from baseline to follow-up or not. These indicator variables were then used as dependent variables in mixed-effect logistic regression models to predict the achievement of each outcome. Unadjusted and covariate-adjusted effects (mean change in effect [β, 95% confidence interval {CI}] for linear regressions and odds ratio [OR, 95% CI] for logistic regressions) were reported. The independent variables in all models included treatment group (TNFi as reference), the baseline value of the outcome variable, and a set of additional covariates (confounders) determined a priori to be likely to influence the outcome measures. Covariates also included those characteristics which were found to be significantly different at the baseline; For monotherapy initiators, covariates included biologic line of therapy, age, duration of RA, gender, work status, history of cardiovascular disease (CVD), CDAI, and morning stiffness; for combination therapy initiators, these were biologic line of therapy, history of CVD, CDAI, patient reported pain, prior use of csDMARDs, and opioids use. These analyses were replicated for monotherapy and combination therapy initiators.

Differences in duration of prior exposure to TNFi were also investigated among patients who had received TNFi earlier. Duration of prior TNFi therapy was used as a proxy for primary and secondary non-response, which may be associated with the effectiveness of subsequent TNFi [20, 21]. The last prior TNFi was identified among patients with a history of at least one prior TNFi, and the proportion of the population was reported with the available information as well as the mean (SD) and median (25th percentile and 75th percentile) duration of therapy. Also, the proportions of the population that persisted on therapy for at least 6 and 12 months were reported. This information was presented for all eligible initiators and by line of therapy. It was assumed that therapy discontinued prior to 6 months would be more likely to be associated with primary non-response.

Lastly, prednisone use was categorized as no use, dose < 10 mg, and dose ≥ 10 mg, and summarized at baseline and at 6 months for TNFi and IL-6Ri monotherapy and combination therapy initiators.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted for mean change in outcomes and prednisone use, where outcomes were reanalyzed by considering binary response outcomes as “non-responders” and imputing continuous outcomes with last observation carried forward (LOCF) for patients who discontinued a biologic prior to the six-months follow-up.

All analyses were performed using Stata 15 and/or SAS 9.4.

Results

Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

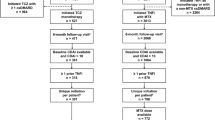

Out of 9682 patients (with moderate or high disease activity) initiating TNFi, 737 and 1315 patients were included in the study as monotherapy and combination therapy initiators, respectively. Similarly, out of 3008 patients (with moderate or high disease activity) initiating IL-6Ri, 286 and 401 patients were included in the study as monotherapy and combination therapy initiators, respectively (Fig. 1).

Patients initiating IL-6Ri (n = 286) vs TNFi monotherapy (n = 737) were older (60.0 vs 55.4 years; P < 0.001), had a longer history of RA (12.2 vs 10.0 years; P = 0.001), higher CDAI at baseline (26.9 vs 24.9; P = 0.02), and were more likely to initiate as third-line therapy (57.0% vs 30.9%; P < 0.001). Further, patients initiating IL-6Ri (n = 401) vs TNFi (n = 1315) combination therapy had higher CDAI at baseline (26.7 vs 24.8; P = 0.007) and were more likely to initiate as third-line therapy (56.4% vs 28.7%; P < 0.001). The detailed baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are described in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively.

Outcome assessments

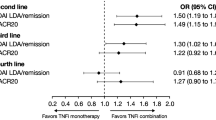

In unadjusted as well as adjusted analyses, no clinically or statistically significant differences were noted for disease activity measures, PROs, and DP between TNFi and IL-6Ri initiators, both as mono- or combination therapy, although there was one exception. In the unadjusted analyses of DP1 (all initiators) among the combination therapy group, higher odds of DP1 presence were noted at 6 months for IL-6Ri when compared with TNFi (17.8% vs 12.6%; OR: 1.64 [1.10, 2.45]; P = 0.015); however, this difference was not seen in the adjusted analyses. One-third of the TNFi and IL-6Ri monotherapy (37.0% vs 32.7%; adjusted OR [aOR]: 0.99 [0.59, 1.67]; Table 3) and combination therapy initiators (36.7% vs 31.2%; aOR: 0.96 [0.66, 1.38]; Table 4) achieved LDA.

In sensitivity analyses, no clinically meaningful differences were noted, with exception of the patient global assessment in the monotherapy initiators; IL-6Ri monotherapy initiators reported higher odds of achieving patient global assessment compared to TNFi monotherapy initiators (OR = 1.62; 1.12–2.35) (Online Supplementary Table 1 and Online Supplementary Table 2).

Among monotherapy (TNFi, n = 319; IL-6Ri, n = 115) and combination therapy (TNFi, n = 617; IL-6Ri, n = 173) initiators with available data on immediate prior TNFi therapy, no meaningful differences were noted between TNFi vs IL 6Ri for the duration of prior TNFi (Table 5).

Further, no meaningful differences were found between TNFi and IL-6Ri initiators (as mono- or combination therapy) for the use of prednisone, with majority of the patients continuing either at their baseline dose or switching to a low dose/no use of prednisone after 6 months of treatment (Online Supplementary Table 3 and Online Supplementary Table 4).

Discussion

In this retrospective real-world evaluation of a b/ts-experienced cohort, TNFi and IL-6Ri initiators had similar clinical outcomes (i.e., disease activity, PROs, and DP), regardless of whether they initiated as monotherapy or combination therapy.

Due to the limited number of real-world biologic-naïve patients initiating IL-6Ri monotherapy in this large retrospective registry, the present study did not evaluate biologic-naïve patients such as the ones included in the H2H trials, systematic literature reviews, and network meta-analysis, which have shown improved clinical outcomes with IL-6Ri when compared with TNFi as monotherapy [9, 10, 22,23,24,25,26]. Although evidence exists for similar clinical outcomes of TNFi and IL-6Ri as combination therapy in biologic-naïve patients [22, 23], no H2H trials in combination with a csDMARD have been conducted so far.

Compared with prior H2H trials [9, 10], patients in the present study were 4–6 years older, and had 2–4 years longer disease duration and half the disease activity (in terms of CDAI) at baseline. The H2H trials compared the efficacy of IL-6Ri with adalimumab in b/ts-naïve RA patients while the present study included the b/ts-experienced patients on IL-6Ri and various TNFi drugs (not limited to adalimumab). Further, the dose of IL-6Ri (tocilizumab) used in the trial [10] was higher as compared with the approved starting dose in clinical practice and the real-world studies, where tocilizumab (subcutaneous or intravenous) was initiated either at low doses or escalated over time as per the patient’s disease activity [27,28,29]. Lastly, the present study included those patients who either had prior use of csDMARDs and/or were on combination therapy with csDMARDs, while the patients in H2H trials were those considered inappropriate candidates for the continued treatment with MTX. All these differences with the populations included in the previous H2H trials may have contributed to a reduced difference in effectiveness between the two treatments in this study [30, 31].

In line with the recently published definition of “difficult-to-treat RA” by the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (i.e., patients who have failed ≥ 2 b/tsDMARD therapies), there were approximately 30% TNFi and 57% IL-6Ri initiators in this study who would fall in this category and thus, would have been classified as refractory to the treatment [32]. Therefore, it is possible that the larger fraction of “difficult-to-treat patients” in the IL-6Ri cohort may have influenced the results in favor of the TNFi cohort. While most of the components included in the “difficult-to-treat RA” definition were adjusted in the present study, some of the factors (such as radiographic progression) were not adjusted.

There was a high proportion of patients who had prior TNFi exposure (88.8%–92.1%) in our study. Literature suggests that a better treatment response would occur when switching from a TNFi to an alternative mechanism of action therapy [33,34,35,36]. Since many patients initiating a TNFi had already failed another TNFi in our b/ts-experienced cohort, we investigated for a potential selection bias in patients who received a follow-on TNFi. Patients with secondary non-response to a TNFi may be more likely to respond to another TNFi than patients with primary non-response [20, 21]. Thus, duration of prior TNFi therapy was used as a proxy for primary and secondary non-response, assuming therapy discontinued within 6 months after initiation would be more likely to be associated with primary non-response. The distribution of prior TNFi discontinuation within or after 6 months of therapy did not differ between the TNFi and IL-6Ri cohorts. However, time on prior TNFi may not have been a good surrogate for primary and secondary non-response [36, 37].

The current analysis had some important differences compared with other studies, which had suggested better outcomes when patients were switched to a different class of biologics after a TNFi failure rather than rechallenged with another TNFi (i.e., cycling) [33,34,35,36]. In our study, CDAI was the primary outcome, whereas in some similar analyses, persistence was used as an outcome [33, 34, 36]; there were only 6 months of follow-up; and approximately one-third of the TNFi initiators and more than half of the IL-6Ri initiators were on their second treatment switch.

Though similar efficacy has been reported for TNFi and other biologics (with different mechanisms of action) in RA, there may be patient subsets with differences noted in clinical outcomes. For example, the AMPLE trial reported similar efficacy for abatacept and adalimumab in all patients with RA [38], while its exploratory analysis showed an association between seropositivity (anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies [ACPA] and/or rheumatoid factor) and better clinical response with abatacept than adalimumab [39]. Similarly, various subsets of RA patients have shown better treatment responses with IL-6Ri compared with TNFi [40,41,42,43]. Recently, machine learning was used to identify a rule to predict the treatment response to sarilumab and suggested that the subset of RA patients with ACPA and CRP > 12.3 mg/L might respond better to sarilumab than to adalimumab [40]; this finding was also validated in a real-world setting [41].

The present study was designed to better inform clinicians about treatment options in patients who have failed prior b/tsDMARDs. The major strengths of this study were its observational real-world nature (reflective of current clinical practices in the US) and the large number of enrolled patients [44]. Further, our methodology was based on logistic regression to control confounders, which is known to yield similar results as propensity score methods in observational studies [45, 46]. However, as with every retrospective observational study, there are limitations. Patients and physicians were unblinded to treatment, and there could be unidentified selection or channeling biases (such as factors affecting adherence to therapy, monitoring requirements, and beliefs and preferences of patients/physicians) that may influence the choice as well as outcomes of a therapy in clinical practice [37, 44]. Also, the visits occurred every 6 months in the study and thus, possible dose changes for the treatments that occurred in between visits might not have been captured accurately in the registry, especially if there were multiple changes. Clinical trials, on the other hand, frequently use pre-determined dose escalation schemas. This difference may have accounted for some of the discrepancy in the study findings. Further, there was no assessment done for the relationship between prednisone and/or non-prescription medications (such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) with b/tsDMARDs, which was outside the scope of current analyses, and may have an impact on the effect of b/tsDMARD therapies. Lastly, the findings for DP1 and DP2 need to be validated in future studies.

In conclusion, no significant differences were noted in clinical outcomes for TNFi vs IL-6Ri initiators (as mono- or combination therapy) in b/ts-experienced patients in this observational study. Results from RCTs have shown that IL-6Ri therapy in biologic-naïve patients is more efficacious than TNFi therapy. This inconsistency may be explained by the fact that the present study included real-world b/ts-experienced patients. Further analyses may help understand the reasons for this inconsistency and optimize the clinical outcomes for patients with RA.

Data availability

Data are available from CorEvitas, LLC through a commercial subscription agreement and are not publicly available. No additional data are available from the authors.

References

Safiri S, Kolahi AA, Hoy D et al (2019) Global, regional and national burden of rheumatoid arthritis 1990–2017: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease study 2017. Ann Rheum Dis 78(11):1463–1471. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215920

Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Barton A et al (2018) Rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 4:18001. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2018.1

Fraenkel L, Bathon JM, England BR et al (2021) 2021 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 73(7):924–939. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.24596

Smolen JS, Landewe RBM, Bijlsma JWJ et al (2020) EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis 79(6):685–699. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216655

Wei ST, Sun YH, Zong SH et al (2015) Serum levels of IL-6 and TNF-alpha may correlate with activity and severity of rheumatoid arthritis. Med SciMonit 21:4030–38. https://doi.org/10.12659/msm.895116

Smolen JS, Aletaha D, McInnes IB (2016) Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 388(10055):2023–2038. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30173-8

Tanaka Y, Mola EM (2014) IL-6 targeting compared to TNF targeting in rheumatoid arthritis: studies of olokizumab, sarilumab and sirukumab. Ann Rheum Dis 73(9):1595–1597. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-205002

Stevenson M, Archer R, Tosh J et al (2016) Adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, tocilizumab and abatacept for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis not previously treated with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and after the failure of conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs only: systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 20(35):1–610. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta20350

Burmester GR, Lin Y, Patel R et al (2017) Efficacy and safety of sarilumab monotherapy versus adalimumab monotherapy for the treatment of patients with active rheumatoid arthritis (MONARCH): a randomised, double-blind, parallel-group phase III trial. Ann Rheum Dis 76(5):840–847. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210310

Gabay C, Emery P, van Vollenhoven R et al (2013) Tocilizumab monotherapy versus adalimumab monotherapy for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (ADACTA): a randomised, double-blind, controlled phase 4 trial. Lancet 381(9877):1541–1550. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60250-0

CorEvitas (2022) Rheumatoid Arthritis Registry. Available from: https://www.corevitas.com/registry/rheumatoid-arthritis. Accessed on 30 Nov 2022

Smolen JS, Aletaha D (2014) Scores for all seasons: SDAI and CDAI. Clin Exp Rheumatol 32:75–79

Curtis JR, Yang S, Chen L et al (2015) Determining the minimally important difference in the clinical disease activity index for improvement and worsening in early rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 67(10):1345–1353. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22606

Wells GA, Tugwell P, Kraag GR et al (1993) Minimum important difference between patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the patient’s perspective. J Rheumatol 20(3):557–560

Greenwood MC, Doyle DV, Ensor M (2001) Does the Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire have potential as a monitoring tool for subjects with rheumatoid arthritis? Ann Rheum Dis 60(4):344–348. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.60.4.344

Anderson JK, Zimmerman L, Caplan L et al (2011) Measures of rheumatoid arthritis disease activity: Patient (PtGA) and Provider (PrGA) Global Assessment of Disease Activity, Disease Activity Score (DAS) and Disease Activity Score with 28-Joint Counts (DAS28), Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI), Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI), Patient Activity Score (PAS) and Patient Activity Score-II (PASII), Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data (RAPID), Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity Index (RADAI) and Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity Index-5 (RADAI-5), Chronic Arthritis Systemic Index (CASI), Patient-Based Disease Activity Score With ESR (PDAS1) and Patient-Based Disease Activity Score without ESR (PDAS2), and Mean Overall Index for Rheumatoid Arthritis (MOI-RA). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 63(Suppl 11):S14–S36. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20621

Hewlett S, Dures E, Almeida C (2011) Measures of fatigue: Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue Multi-Dimensional Questionnaire (BRAF MDQ), Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue Numerical Rating Scales (BRAF NRS) for severity, effect, and coping, Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire (CFQ), Checklist Individual Strength (CIS20R and CIS8R), Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS), Functional Assessment Chronic Illness Therapy (Fatigue) (FACIT-F), Multi-Dimensional Assessment of Fatigue (MAF), Multi-Dimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI), Pediatric Quality Of Life (PedsQL) Multi-Dimensional Fatigue Scale, Profile of Fatigue (ProF), Short Form 36 Vitality Subscale (SF-36 VT), and Visual Analog Scales (VAS). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 63(Suppl 11):S263–S286. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20579

Nijs J, Torres-Cueco R, van Wilgen CP et al (2014) Applying modern pain neuroscience in clinical practice: criteria for the classification of central sensitization pain. Pain Physician 17(5):447–457

Choy E, Bykerk V, Lee CY et al (2022) Disproportionate articular pain is a frequent phenomenon in rheumatoid arthritis and responds to treatment with sarilumab. Rheumatology (Oxford) keac659. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keac659

Bombardieri S, Ruiz AA, Fardellone P et al (2007) Effectiveness of adalimumab for rheumatoid arthritis in patients with a history of TNF-antagonist therapy in clinical practice. Rheumatology (Oxford) 46(7):1191–1199

Blom M, Kievit W, Fransen J et al (2007) Effectiveness of switch to a second anti-TNF-α in primary nonresponders, secondary nonresponders and failure due to adverse events [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum 56(Suppl):S165

Buckley F, Finckh A, Huizinga TWJ et al (2015) Comparative efficacy of novel DMARDs as monotherapy and in combination with methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis patients with inadequate response to conventional DMARDs: a network meta-analysis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 21(5):409–23. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2015.21.5.409

Jansen JP, Buckley F, Dejonckheere F et al (2014) Comparative efficacy of biologics as monotherapy and in combination with methotrexate on patient reported outcomes (PROs) in rheumatoid arthritis patients with an inadequate response to conventional DMARDs–a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 12:102. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-12-102

Best JH, Kuang Y, Jiang Y et al (2021) Comparative efficacy (DAS28 remission) of targeted immune modulators for rheumatoid arthritis: a network meta-analysis. Rheumatol Ther 8(2):693–710. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-021-00322-y

Choy EH, Bernasconi C, Aassi M et al (2017) Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with anti-tumor necrosis factor or tocilizumab therapy as first biologic agent in a global comparative observational study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 69(10):1484–1494. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23303

Benson R, Zhao SS, Goodson N et al (2020) Biologic monotherapy in the biologic naive patient with rheumatoid arthritis (RA): results from an observational study. Rheumatol Int 40(7):1045–1049. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04531-6

Prescribing information (2022) Tocilizumab. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/125276s120s121lbl.pdf. Accessed on 30 Nov 2022

Pappas DA, John A, Curtis JR et al (2016) Dosing of Intravenous Tocilizumab in a Real-World Setting of Rheumatoid Arthritis: Analyses from the Corrona Registry. Rheumatol Ther 3(1):103–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-016-0028-0

Punekar R, Choi J, Boklage S et al (2019) Real-World Dose Modification Patterns of Subcutaneous Tocilizumab Among Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Am Health Drug Benefits 12(8):400–409

Kilcher G, Hummel N, Didden EM et al (2018) Rheumatoid arthritis patients treated in trial and real world settings: comparison of randomized trials with registries. Rheumatology (Oxford) 57(2):354–369. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kex394

Eichler HG, Abadie E, Breckenridge A et al (2011) Bridging the efficacy-effectiveness gap: a regulator’s perspective on addressing variability of drug response. Nat Rev Drug Discov 10(7):495–506. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd3501

Nagy G, Roodenrijs NMT, Welsing PM et al (2021) EULAR definition of difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 80(1):31–35. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217344

Chastek B, Becker LK, Chen CI et al (2017) Outcomes of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor cycling versus switching to a disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug with a new mechanism of action among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Med Econ 20(5):464–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2016.1275653

Wei W, Knapp K, Wang L et al (2017) Treatment persistence and clinical outcomes of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor cycling or switching to a new mechanism of action therapy: real-world observational study of rheumatoid arthritis patients in the United States with prior tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy. Adv Ther 34(8):1936–1952. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-017-0578-8

Migliore A, Pompilio G, Integlia D et al (2021) Cycling of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors versus switching to different mechanism of action therapy in rheumatoid arthritis patients with inadequate response to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors: a Bayesian network meta-analysis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 13:1759720X211002682. https://doi.org/10.1177/1759720X211002682

KarpesMatusevich AR, Duan Z, Zhao H et al (2021) Treatment sequences after discontinuing a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a comparison of cycling versus swapping strategies. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 73(10):1461–1469. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.24358

Zhang J, Shan Y, Reed G et al (2011) Thresholds in disease activity for switching biologics in rheumatoid arthritis patients: experience from a large U.S. cohort. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 63(12):1672–79. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20643

Schiff M, Weinblatt ME, Valente R et al (2014) Head-to-head comparison of subcutaneous abatacept versus adalimumab for rheumatoid arthritis: two-year efficacy and safety findings from AMPLE trial. Ann Rheum Dis 73(1):86–94. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203843

Fleischmann R, Weinblatt M, Ahmad H et al (2019) Efficacy of abatacept and adalimumab in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis with multiple poor prognostic factors: post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled clinical trial (AMPLE). Rheumatol Ther 6(4):559–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-019-00174-7

Rehberg M, Giegerich C, Praestgaard A et al (2021) Identification of a rule to predict response to sarilumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis using machine learning and clinical trial data. Rheumatol Ther 8(4):1661–1675. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-021-00361-5

Yun H, Curtis J, Chen L et al (2021) Real world validation of a rule to predict response to sarilumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: analysis from the RISE Registry [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 73(Suppl 9). https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/real-world-validation-of-a-rule-to-predict-response-to-sarilumab-in-patients-with-rheumatoid-arthritis-analysis-from-the-rise-registry/. Accessed 10 Apr 2023

Nakayama Y, Hashimoto M, Watanabe R et al (2021) Favorable clinical response and drug retention of anti-IL-6 receptor inhibitor in rheumatoid arthritis with high CRP levels: the ANSWER cohort study. Scand J Rheumatol 13:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/03009742.2021.1947005

Genovese MC, Burmester GR, Hagino O et al (2020) Interleukin-6 receptor blockade or TNFalpha inhibition for reducing glycaemia in patients with RA and diabetes: post hoc analyses of three randomised, controlled trials. Arthritis Res Ther 22(1):206. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-020-02229-5

Blonde L, Khunti K, Harris SB et al (2018) Interpretation and impact of real-world clinical data for the practicing clinician. Adv Ther 35(11):1763–1774. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-018-0805-y

Shah BR, Laupacis A, Hux JE et al (2005) Propensity score methods gave similar results to traditional regression modeling in observational studies: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 58(6):550–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.10.016

Stürmer T, Joshi M, Glynn RJ et al (2006) A review of the application of propensity score methods yielded increasing use, advantages in specific settings, but not substantially different estimates compared with conventional multivariable methods. J Clin Epidemiol 59:437–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.07.004

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the investigators and patients who participated in the CorEvitas Rheumatoid Arthritis Registry. Statistical support for the sensitivity analysis was provided by Page Moore (CorEvitas). Medical writing support for this manuscript was provided by Vasudha Chachra (Sanofi) and Nupur Chaubey (former employee of Sanofi).

Funding

The registry was sponsored by CorEvitas, LLC and the analysis was funded by Sanofi and Regeneron. Access to study data was limited to CorEvitas and CorEvitas statisticians completed all the analysis; all authors contributed to the interpretation of the results. CorEvitas has been supported through contracted subscriptions in the last two years by AbbVie, Amgen, Arena, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Chugai, Eli Lilly and Company, Genentech, Gilead, GSK, Janssen, LEO, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfizer Inc., Regeneron, Sanofi, Sun, and UCB.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

COB, VPB, SF, KF, JCJ, DAP, TB, JMK, and EC contributed substantially to the conception and design of the work related to this document. COB, VPB, JCJ, DAP, JMK, and EC contributed substantially to the data acquisition for the work related to this document. All authors contributed substantially to the data analysis or interpretation of the work related to this document, reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all participating investigators obtained full ethics or IRB approval for conducting research in patients. The Sponsor approval and continuing review were obtained through a central IRB (NEIRB number: 120160610). For academic investigative sites that did not receive a waiver to use the central IRB, approval was obtained from the respective governing IRBs, and documentation of approval was submitted to the Sponsor prior to initiating any study procedures. All registry patients were required to provide written informed consent prior to participation.

Previous publications

The data in part were presented at American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Convergence 2021 (November 01–10, 2021).

Reference: Sebba A, Bingham C, Bykerk V, et al. (2021) Comparative Effectiveness of TNF Inhibitor vs IL-6 Receptor Inhibitor as Monotherapy or Combination Therapy with Methotrexate in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: Analysis from CorEvitas’ RA Registry [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 73 (suppl 9). Accessed on: November 30, 2022.

Competing interests

AS received consulting fees from Sanofi, Lilly, Amgen, and Gilead, and honoraria from Sanofi, Lilly, and Genentech. COB received consulting fees from AbbVie, Gilead, Lilly, Janssen, Regeneron/Sanofi, and Pfizer, and grants/contracts from BMS. VPB received consulting fees from Amgen, BMS, Gilead, Genzyme Corp, Regeneron, and UCB; grants for research and analysis (in kind) from Amgen, BMS, Genzyme Corp., Pfizer, Regeneron, UCB, and Sanofi Aventis; and research funds (to institution) from Amgen and BMS. SF is an employee of Sanofi and may hold stocks or stock options and patents (planned, issued, or pending) in Sanofi. KF is an employee of Sanofi and may hold stocks or stock options. JCJ was an employee of CorEvitas, LLC at the time of this analysis. DAP received consulting fees from Sanofi, AbbVie, Gtech Roche Hellas, and Novartis; has leadership or fiduciary role (paid or unpaid) for CorEvitas, LLC, and is on Board of Directors for Corrona Research Foundation; is an employee of CorEvitas, LLC, and may hold stocks or stock options. TB was an employee of CorEvitas, LLC at the time of this analysis. SSD was an employee of CorEvitas, LLC at the time of this analysis. JMK is a consultant for CorEvitas, LLC. MU is an employee of CorEvitas, LLC. EC received grants/contacts from BioCancer, Biogen, Pfizer, and Sanofi; consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Biocon, BMS, Chugai Pharma, Eli Lilly, Galapagos, Gilead, Janssen, Merck Serono, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi, and UCB; honoraria from Amgen, Eli Lilly, Galapagos, Gilead, Pfizer, Roche, and Sanofi; support for attending meetings and/or travel from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, and Gilead; and fees for participation in Data Safety Monitoring/Advisory Board of Eli Lilly, Galapagos, Gilead, Roche, Sanofi, and UCB.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jud C Janak, Taylor Blachley and Swapna S Dave: Affiliation at the time of study.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sebba, A., Bingham, C.O., Bykerk, V.P. et al. Comparative effectiveness of TNF inhibitor vs IL-6 receptor inhibitor as monotherapy or combination therapy with methotrexate in biologic-experienced patients with rheumatoid arthritis: An analysis from the CorEvitas RA Registry. Clin Rheumatol 42, 2037–2051 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-023-06588-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-023-06588-7