Abstract

Introduction/objectives

Lesinurad, in combination with allopurinol, has been approved for treatment of patients with gout which do not reach therapeutic serum urate target with xanthine oxidase inhibitors monotherapy. The study aimed to assess the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of adding lesinurad to allopurinol as second-line therapy, compared to febuxostat for patients with gout in Spain.

Method

A Markov model representing disease evolution was used to estimate the lifetime accumulated cost and benefits in terms of quality-adjusted-life-year (QALY). Patients could either continue with second-line treatment with lesinurad (200 mg/daily) plus allopurinol (400 mg/daily) or febuxostat (80 mg/daily) switch to allopurinol monotherapy (271 mg/daily) in case of intolerance or discontinue treatment. The treatment’s efficacy captured in the transition probabilities between health states were derived from CLEAR and EXCEL trials. Quality of life related to gout severity and flare frequency was considered by means of utilities. The total cost estimation (€, 2019) included drug acquisition cost, disease monitoring, and flare management cost. Unitary local costs derived from databases and literature. A 3% annual discount rate was applied for cost and outcomes.

Results

Lesinurad plus allopurinol provided higher QALYs (14.79) than febuxostat (14.69). Total accrued cost/patient was lower with lesinurad and allopurinol (€50,631.51) versus febuxostat (€56,698.64). Lesinurad plus allopurinol resulted more effective and less costly (dominant option) versus febuxostat.

Conclusions

Lesinurad plus allopurinol therapy compared with febuxostat seems an effective option for the management of hyperuricemia in patients who did not reach serum urate target to previous allopurinol monotherapy, associated to cost-savings for the Spanish Health System.

Key Points | |

• Lesinurad, in combination with allopurinol, has been recently authorized as second-line treatment of hyperuricemia in gout patients. | |

• Lesinurad plus allopurinol provided higher effectiveness in terms of quality-adjusted-life-years (14.79) than febuxostat (14.69). | |

• Lesinurad plus allopurinol resulted less costly (total cost/per patient) compared with febuxostat. | |

• Lesinurad plus allopurinol resulted a dominant option compared with febuxostat. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gout is a chronic, progressive, life-limiting disease [1] caused by persistent elevation of serum uric acid (sUA) levels (hyperuricemia) and characterized by the accumulation of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals in joints [2]. Acute gout flares are intensely painful and associated with functional impairment and more advance disease is characterized by tophi, frequent flares, and damage to bone and soft tissues [1, 3] leading to a considerable impact on health-related quality of life, with all aspects of daily life potentially affected [4].

In addition, gout management is associated with a substantial economic impact in healthcare systems in terms of direct costs and resource use [4] and indirect costs due to work absenteeism and lost productivity [1, 3]. The economic burden of gout is also greater for patients with inadequately-controlled gout compared with controlled disease [5].

Gout is more common in men and affects 0.5–1% of the adult population in Western countries, making it the most common form of inflammatory arthritis [6]. In Spain, a recent study, has reported a gout prevalence in adults aged 20 of 2.4% [7].

According to the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations for the management of gout [8], the aim of gout therapy is to lower sUA below the saturation threshold for MSU crystal formation in order to reduce the occurrence of acute flares, resolve tophi, and prevent joint damage. In patients with normal kidney function, allopurinol, a xanthine oxidase inhibitor (XOI), is recommended as first-line therapy [8]; however, about a third of those patients do not achieve the sUA target level and need to be treated with second-line therapy [9].

Febuxostat, a potent non-purine selective XOI, is indicated in the treatment of chronic hyperuricemia in conditions where urate deposition has already occurred (including a history or presence of tophus and/or gouty arthritis) [10].

Furthermore, emerging uricosuric has shown promising results when combined with allopurinol [8]. Lesinurad, a new selective uric acid reabsorption inhibitor, was approved by Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2015 in combination with a XOI for the adjunctive treatment of hyperuricemia in adult gout patients who have not achieved target sUA levels with an adequate dose of a XOI alone [11].

Usually, the inclusion of new treatment options represents an increase in pharmaceutical costs which can be compensated or even lead to savings in the total costs by a lower resource consumption in the management of disease.

The purpose of the present study was to assess the cost-effectiveness of lesinurad in combination with allopurinol versus febuxostat in adults with gout previously treated with allopurinol monotherapy, in Spain.

Material and methods

Model structure

A state-transition Markov model developed in Microsoft Excel® was adapted to estimate costs and health benefits accrued for a hypothetical cohort of adult patients in the treatment of gout. The structure was consistent with the cost-effectiveness analysis model of lesinurad appraised by the National Institute for Health Care Excellence (NICE) [12].

The model was designed to represent the natural evolution of gout and involves 6 mutually exclusive health states defined by sUA category < 5 mg/dL, 5 to < 6 mg/dL, 6 to < 8 mg/dL, 8 to < 10 mg/dL, ≥ 10 mg/dL, and dead (Fig. 1). In each health state, the model distinguishes between tophaceous and non-tophaceous gout.

Transitions between the health states were conducted in 6-month cycles according the efficacy end points assessment in CLEAR trials (Combining Lesinurad with Allopurinol Standard of Care in Inadequate Responders) [13, 14]. Patients can enter the model from every sUA health states and after each 6-month cycle can either continuing second-line urate lowering therapy (ULT), switch to allopurinol monotherapy, discontinuing treatment, or die. Also, in each cycle the probability of developing acute gout flares at any sUA was considered.

The therapeutic alternatives compared in the model included lesinurad 200 mg once daily co-administered at the same time with allopurinol 400 mg and febuxostat 80 mg once daily.

The analysis was carried out from the perspective of the Spanish National Healthcare System (NHS).

The time horizon of the analysis was lifetime and a discount rate of 3% was applied to costs and health outcomes, in accordance with the last published recommendations for performing economic evaluations in Spain [15]. Half-cycle correction was not applied in line with recommendations from some authors published in literature [16].

Population

According to the pooled intention to treat population in CLEAR studies [13, 14], the model considered a hypothetical cohort of gout patients who progress to second-line ULT after failing to achieve target sUA of < 6 mg/dL on a clinically appropriate dose of allopurinol alone. To estimate the male and female proportion, a prevalence of gout equal to 4.55% for males and a 0.38% for females (weighted on the Spanish inhabitants older than 20 years of age [17]), was considered. The cohort of patients was distributed according to their sUA concentration (18.8% < 6 mg/dL, 63.7% 6–8 mg/dL, 15.2% 8–10 mg/dL, and 2.3% ≥ 10 mg/dL) [13, 14].

Clinical data

To evaluate the efficacy of lesinurad added to allopurinol versus febuxostat as second-line therapy for the treatment of gout in patients failing to achieve target sUA on first-line allopurinol monotherapy, an unadjusted indirect treatment comparison was conducted. The clinical efficacy of lesinurad added to allopurinol was based on aggregated data from CLEAR 1 [13] and CLEAR 2 [14] trials and clinical efficacy of febuxostat was based on APEX (Allopurinol and Placebo-Controlled Efficacy Study of Febuxostat) [18], FACT (Febuxostat versus Allopurinol-Controlled Trial) [19], and CONFIRMS [20] trials and in long-term EXCEL study (fEbuXostat/allopurinol comparative extension long-term study) [21].

Gout-associated mortality risk was excluded from analysis due to overall survival data were not available from CLEAR 1 [13] and CLEAR 2 [14] studies, assuming, conservatively, that hyperuricemia had no impact on patient survival.

Pooled efficacy data from CLEAR studies was extrapolated to estimate the transition probabilities (Table 1), treatment discontinuation rates and acute gout flares rates (Table 1) for lesinurad plus allopurinol treatment. In case of febuxostat, transition probabilities were obtained from EXCEL trial [21] (Table 1), while treatment discontinuation rates were obtained from the pooled data of the APEX [18], FACT [19], and CONFIRMS [20] studies for the first year and from the EXCEL trial for long-term (Table 1). Febuxostat-specific acute gout flare rates were estimated based on FACT [19] and EXCEL [21] clinical trial data (Table 1). For both treatments, tophus incidence data by sUA levels provided from literature [23] while tophus resolution rate were derived from study 306 [24] and study 307 [25].

Utilities

To estimate the quality-adjusted-life-years (QALYs), utility values associated with each health state were considered depending on the tophi status (non-tophaceous gout versus tophaceous gout) and the number of flares affecting the patients during each 6-month cycle (Table 1). Utility values were estimated based on SF-6D scores derived from post hoc analyses of SF-36 results at month 6 and month 12 in the CLEAR trials [22].

Resource use and costs

In line with the perspective, only direct costs were considered which included pharmaceutical costs, health state medical resource costs, and those associated with treatment and management of acute gout flares.

The pharmaceutical costs reflected drugs-acquisition costs which were estimated based on the ex-factory prices [26] with national mandatory deductions [27] (Table 2). The average cost of allopurinol monotherapy administered in first-line was estimated as the weighted sum of costs per dose category (35.82% 200 mg/day, 57.76% 300 mg/day, and 6.42% 400 mg/day). As the initiation of ULT is initially associated with increased risk of gout flares [29], the model considered prophylaxis treatment with colchicine (80% 1 mg/day and 20% 0.50 mg/day) during the first 6 months in lesinurad plus allopurinol and during the first 5 months in febuxostat treatment. Patients developing acute gout flares during treatment were managed by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (59.10%), corticosteroids (30.50%), or colchicine (10.40%).

Disease management costs were estimated based on health resource consumption referred to specialist visits, medical examinations and diagnostic test, which was provided by a rheumatologist with wide expertise and knowledge about gout (Table 2). The unitary costs of specialist visits and diagnostic tests were obtained from local national database of health costs [28].The cost of an acute gout flare management was obtained from the literature [30].

All costs were expressed in euros, 2019 values, and in those costs obtained from literature, the cost was inflated in 2019 based on the Spanish general consumer price index [17].

Sensitivity analysis

Both, one-way (OWA) and probabilistic sensitivity analyses (PSA) were performed to evaluate the robustness of the model and to determine the uncertainty surrounding model parameters. For the OWA, the following parameters were varied: discount rate (0% and 5%), allopurinol alternative dose in combination (300 mg/day), health state medical resource costs (± 10%), medical costs per flare treated (±10%), and considering a mortality ratio based on literature [31]. Additional scenario, considering the management cost of adverse events (AEs) (rheumatology visit per AE, €152.15 [28]) was also tested based on safety data [13, 14, 18,19,20].

PSA were performed using 1000 Monte Carlo simulations. The value of each key parameter would vary according a specific probability distribution assigned to each parameter. Beta distribution were applied for transition probabilities and discontinuation rates; log-normal distribution for mortality ratios and monitoring costs; and normal distribution for acute gout flares rate, medical costs of acute gout flares, and utilities.

Results

Base case

Over a lifetime horizon, 67.86% of lesinurad plus allopurinol-treated patients achieved sUA < 6 mg/dl versus 54.94% with febuxostat. Also, the mean number of flares per patient/year and the mean number of patient/years with tophi was lower with lesinurad plus allopurinol (8.06 and 9.30, respectively) than febuxostat-treated patients (9.42 and 10.90, respectively). In terms of quality of life, lesinurad plus allopurinol treatment was more effective than febuxostat treatment, yielding 14.79 QALY per patient versus 14.69 QALYs (Table 3). Regarding the total expenditure, lesinurad plus allopurinol represented a total cost of €50,631.51 per patient compared with €56,698.64 with febuxostat. Flare costs were lower in the lesinurad plus allopurinol (€44,561.08) comparing to febuxostat treatment (€52,883.11) whereas pharmaceutical and health state medical costs were higher (incremental costs €1511.43 and €743.47, respectively) (Table 3). The analysis indicated that lesinurad added to allopurinol as a second-line treatment was a dominant option, more effective and less costly, relative to febuxostat treatment.

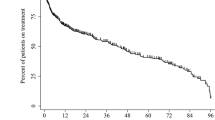

Sensitivity analysis

Regarding the OWA, lesinurad added to allopurinol remained as a dominant option in all the scenarios tested. The scenario having most influence on the results was considering alternative mortality risk based on literature evidence [31], followed by medical cost per flare treatment (Fig. 2).

A cost-effectiveness plane (Fig. 3a) and a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (Fig. 3b) were used to show PSA results. Out of 1000 Monte-Carlo simulations, 97.60% of the cases presented an ICUR under a €25,000 per QALY gained willingness-to-pay threshold [32].

Discussion

The results obtained in this analysis suggest a higher effectiveness of treatment with lesinurad plus allopurinol due to the greater number of patients at target sUA levels (< 6 mg/dl) which entails improvements in quality of life and cost savings of €6067.13 per patient.

The present study is the first cost-effectiveness analysis of lesinurad added to allopurinol in second-line treatment of patients with gout developed from the perspective of the Spanish NHS. The model used for this cost-effectiveness analysis was employed by NICE as a tool for the development of single technology appraisal [12] and has been used for the evaluation of the efficiency of lesinurad added to allopurinol versus febuxostat from the perspective of the Italian NHS, estimating an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of €77.53 per QALY gained, which was also considered a cost-effective option [33].

This analysis has some potential limitations, some of which are inherent to this type of pharmacoeconomic models. Due to the lack of a direct comparison between lesinurad and febuxostat, the clinical parameters used in the analysis have been extracted from different sources; however, all parameters are based on publications with high level of clinical evidence and have been validated by expert rheumatologist. In the absence of head-to head clinical trial evidence, indirect treatment comparisons provide useful evidence and represent a valuable set of analytical tools to inform clinical evidence in cost-effectiveness analysis [34]. Other limitation was the absence of mortality risk associated with gout in the model, despite a recent study concluded that mortality risk is associated with both severity and highest levels of sUA compared with the general population [3]. Nevertheless, due to lack of survival end points on clinical trials [13, 14], the analysis assuming, conservatively, that hyperuricemia has no impact on survival. Another key parameter is the quality of life. Due to the lack of utility values availability in the Spanish population, utilities values are taken from mean SF-6D scores in CLEAR studies. However, these trial-based utilities are consistent with other utility value reported in the literature [30, 35,36,37,38,39,40,41].

Despite the limitations described previously, the results of the sensitivity analysis confirm that the uncertainty associated with the parameters used in the modeling did not represent a significant deviation from the results obtained in the base case. The PSA results show that the cost per additional QALY gained with lesinurad plus allopurinol compared with febuxostat remains below the last cost-effectiveness threshold published by Health Technology Assessment Agencies in our country [32].

References

Grassi W, De Angelis R (2012) Clinical features of gout. Reumatismo 63:238–245. https://doi.org/10.4081/reumatismo.2011.238

Neogi T, Jansen TL, Dalbeth N, Fransen J, Schumacher HR, Berendsen D, Brown M, Choi H, Edwards NL, Janssens HJ, Lioté F, Naden RP, Nuki G, Ogdie A, Perez-Ruiz F, Saag K, Singh JA, Sundy JS, Tausche AK, Vazquez-Mellado J, Yarows SA, Taylor WJ (2015) Gout classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European league against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheumatol 67:2557–2568. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.39254

Perez-Ruiz F, Martínez-Indart L, Carmona L, Herrero-Beites AM, Pijoan JI, Krishnan E (2014) Tophaceous gout and high level of hyperuricaemia are both associated with increased risk of mortality in patients with gout. Ann Rheum Dis 73:177–182. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202421

Shields GE, Beard SM (2015) A systematic review of the economic and humanistic burden of gout. Pharmacoeconomics 33:1029–1047. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-015-0288-5

Rai SK, Burns LC, De Vera MA, Haji A, Giustini D, Choi HK (2015) The economic burden of gout: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 45:75–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.02.004

Mikuls TR, Saag KG (2006) New insights into gout epidemiology. Curr Opin Rheumatol 18:199–203. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.bor.0000209435.89720.7c

Seoane-Mato D, Sánchez-Piedra C, Díaz-González F, Bustabad S (2018) Prevalence of rheumatic diseases in adult population in Spain. EPISER 2016 study. Ann Rheum Dis 77:535–536. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-eular.6463

Richette P, Doherty M, Pascual E, Barskova V, Becce F, Castañeda-Sanabria J, Coyfish M, Guillo S, Jansen TL, Janssens H, Lioté F, Mallen C, Nuki G, Perez-Ruiz F, Pimentao J, Punzi L, Pywell T, So A, Tausche AK, Uhlig T, Zavada J, Zhang W, Tubach F, Bardin T (2017) 2016 updated EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of gout. Ann Rheum Dis 76:29–42. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209707

Perez-Ruiz F, Sanchez-Piedra CA, Sanchez-Costa JT, Andrés M, Diaz-Torne C, Jimenez-Palop M, De Miguel E, Moragues C, Sivera F (2018) Improvement in diagnosis and treat-to-target management of hyperuricemia in gout: results from the GEMA-2 transversal study on practice. Rheumatol Ther 5:243–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-017-0091-1

EMA (2019) Adenuric: Summary of product characteristics. [Internet]. European Medicines Agency. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/adenuric-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 15 mar 2019

EMA (2017) Zurampic: summary of product characteristics. [Internet]. European Medicines Agency. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/zurampic-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 15 mar 2019

NICE (2016) Single technology appraisal. Lesinurad for treating chronic hyperuricaemia in people with gout [IT761]. [internet]. National Institute for health and care excellence. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta506/documents/committee-papers. Accessed 8 mar 2019

Saag KG, Fitz-Patrick D, Kopicko J, Fung M, Bhakta N, Adler S, Storgard C, Baumgartner S, Becker MA (2017) Lesinurad combined with allopurinol: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in gout patients with an inadequate response to standard-of-care allopurinol (a US-based study). Arthritis Rheumatol 69:203–212. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.39840

Bardin T, Keenan RT, Khanna PP, Kopicko J, Fung M, Bhakta N, Adler S, Storgard C, Baumgartner S, So A (2017) Lesinurad in combination with allopurinol: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with gout with inadequate response to standard of care (the multinational CLEAR 2 study). Ann Rheum Dis 76:811–820. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209213

López-Bastida J, Oliva J, Antoñanzas F, García-Altés A, Gisbert R, Mar J, Puig-Junoy J (2010) Spanish recommendations on economic evaluation of health technologies. Eur J Health Econ 11:513–520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-010-0244-4

Barendregt JJ (2009) The half-cycle correction: banish rather than explain it. Med Decis Mak 29:500–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X09340585

INE (2019) [Internet]. Instituto Nacional de Estadística. https://www.ine.es/. Accessed 2 Jan 2019

Schumacher HR Jr, Becker MA, Wortmann RL, Macdonald PA, Hunt B, Streit J, Lademacher C, Joseph-Ridge N (2008) Effects of febuxostat versus allopurinol and placebo in reducing serum urate in subjects with hyperuricemia and gout: a 28-week, phase III, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group trial. Arthritis Rheum 59:1540–1548. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.24209

Becker MA, Schumacher HR Jr, Wortmann RL, MacDonald PA, Eustace D, Palo WA, Streit J, Joseph-Ridge N (2005) Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout. N Engl J Med 353:2450–2461. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa050373

Becker MA, Schumacher HR, Espinoza LR, Wells AF, MacDonald P, Lloyd E, Lademacher C (2010) The urate-lowering efficacy and safety of febuxostat in the treatment of the hyperuricemia of gout: the CONFIRMS trial. Arthritis Res Ther 12:63. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2978

Becker MA, Schumacher HR, MacDonald PA, Lloyd E, Lademacher C (2009) Clinical efficacy and safety of successful longterm urate lowering with febuxostat or allopurinol in subjects with gout. J Rheumatol 36:1273–1282. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.080814

Pérez-Ruiz F, So A, Kandaswamy P, Karra R, Keton K, Perk S, Bardin T (2018) Estimating health-related quality of life for gout patients: a post-hoc analysis of utilities from the clear trials. Ann Rheum Dis 77:132. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-eular.6822

Yu T-F, Gutman A (1967) Principles of current management of primary gout. Am J Med Sci 254:893–907. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000441-196712000-00019

Saag K, Becker MA, Storgard C, Fung M, Bhakta N, Adler S, Hu J, Bardin T (2016) Examination of serum uric acid (sUA) lowering and safety with extended lesinurad + allopurinol treatment in subjects with gout. Ann Rheum Dis 75:371–37371. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-eular.2727

Dalbeth N, Jones G, Terkeltaub R, Khanna D, Fung M, Baumgartner S, Perez-Ruiz F (2019) Efficacy and safety during extended treatment of lesinurad in combination with febuxostat in patients with tophaceous gout: CRYSTAL extension study. Arthritis Res Ther 21:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-018-1788-4

Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Farmacéuticos (2019) Base de datos del Conocimiento Sanitario - Bot Plus 2.0 [Internet]. Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Farmacéuticos. https://botplusweb.portalfarma.com/. Accessed 4 Jan 2019

MSCBS (2019) Relación informativa de medicamentos afectados por las deducciones establecidas en el Real Decreto Ley 8/2010 de 20 de mayo por el que se adoptan medidas extraordinarias para la reducción del déficit público. [Internet]. Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social. https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/farmacia/pdf/DeduccionesENERO19.pdf. Accesed 4 jan 2019

Oblikue Consulting (2019) Base de datos de costes sanitarios eSalud [Internet]. Oblikue Consulting. http://www.oblikue.com/bddcostes/. Accessed 3 Jan 2019

Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T, Pascual E, Barskova V, Conaghan P, Gerster J, Jacobs J, Leeb B, Lioté F, McCarthy G, Netter P, Nuki G, Perez-Ruiz F, Pignone A, Pimentão J, Punzi L, Roddy E, Uhlig T, Zimmermann-Gòrska I, EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (2006) EULAR evidence-based recommendations for gout. Part II: management. Report of a task force of the EULAR standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 65:1312–1324. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2006.055269

Pérez-Ruiz F, Díaz-Torné C, Carcedo D (2016) Cost-effectiveness analysis of febuxostat in patients with gout in Spain. J Med Econ 19:604–610. https://doi.org/10.3111/13696998.2016.1149482

Degli Esposti L, Desideri G, Saragoni S, Buda S, Pontremoli R, Borghi C (2016) Hyperuricemia is associated with increased hospitalization risk and healthcare costs: evidence from an administrative database in Italy. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 26:951–961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2016.06.008

Vallejo-Torres L, García-Lorenzo B, Serrano-Aguilar P (2018) Estimating a cost-effectiveness threshold for the Spanish NHS. Health Econ 27:746–761. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3633

Ruggeri M, Basile M, Drago C, Rolli FR, Cicchetti A (2018) Cost-effectiveness analysis of Lesinurad/allopurinol versus Febuxostat for the Management of Gout/hyperuricemia in Italy. Pharmacoeconomics 36:625–636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-018-0643-4

Jansen JP, Fleurence R, Devine B, Itzler R, Barrett A, Hawkins N, Lee K, Boersma C, Annemans L, Cappelleri JC (2011) Interpreting indirect treatment comparisons and network meta-analysis for health-care decision making: report of the ISPOR task force on indirect treatment comparisons good research practices: part 1. Value Health 14:417–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2011.04.002

Khanna D, Ahmed M, Yontz D, Ginsburg SS, Park GS, Leonard A, Tsevat J (2008) The disutility of chronic gout. Qual Life Res 17:815–822. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-008-9355-0

DiBonaventura M, Andrews LM, Yadao AM, Kahler KH (2012) The effect of gout on healthrelated quality of life, work productivity, resource use and clinical outcomes among patients with hypertension. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 12:821–829. https://doi.org/10.1586/erp.12.60

Khanna PP, Nuki G, Bardin T, Tausche AK, Forsythe A, Goren A, Vietri J, Khanna D (2012) Tophi and frequent gout flares are associated with impairments to quality of life, productivity, and increased healthcare resource use: results from a cross-sectional survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes 10:117. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-10-117

Strand V, Khanna D, Singh JA, Forsythe A, Edwards NL (2012) Improved health-related quality of life and physical function in patients with refractory chronic gout following treatment with pegloticase: evidence from phase III randomized controlled trials. J Rheumatol 39:1450–1457. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.111375

Beard SM, von Scheele BG, Nuki G, Pearson IV (2014) Cost-effectiveness of febuxostat in chronic gout. Eur J Health Econ 15:453–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-013-0486-z

Jutkowitz E, Choi HK, Pizzi LT, Kuntz KM (2014) Cost-effectiveness of allopurinol and febuxostat for the management of gout. Ann Intern Med 161:617–626. https://doi.org/10.7326/M14-0227

Spaetgens B, Tran-Duy A, Wijnands J, van der Linden S, Boonen A (2015) Health and utilities in patients with gout under the care of a rheumatologist. Arthritis Care Res 67:1128–1136. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22551

Funding

This study was funded by Grünenthal Spain.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

María Presa and Itziar Oyagüez are employees of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research Iberia (PORIB), a consultant company specializing in healthcare outcomes research and economic evaluation of health technology, which received unrestricted financial support by Grünenthal to assist with the local adaptation of the model and manuscript drafting. Fernando Pérez-Ruiz has received fees from Grünenthal for advisory work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Presa, M., Pérez-Ruiz, F. & Oyagüez, I. Second-line treatment with lesinurad and allopurinol versus febuxostat for management of hyperuricemia: a cost-effectiveness analysis for Spanish patients. Clin Rheumatol 38, 3521–3528 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04739-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04739-3