Abstract

Introduction

Biologics have improved the treatment of rheumatic diseases, resulting in better outcomes. However, their high cost limits access for many patients in both North America and Latin America. Following patent expiration for biologicals, the availability of biosimilars, which typically are less expensive due to lower development costs, provides additional treatment options for patients with rheumatic diseases. The availability of biosimilars in North American and Latin American countries is evolving, with differing regulations and clinical indications.

Objective

The objective of the study was to present the consensus statement on biosimilars in rheumatology developed by Pan American League of Associations for Rheumatology (PANLAR).

Methods

Using a modified Delphi process approach, the following topics were addressed: regulation, efficacy and safety, extrapolation of indications, interchangeability, automatic substitution, pharmacovigilance, risk management, naming, traceability, registries, economic aspects, and biomimics. Consensus was achieved when there was agreement among 80% or more of the panel members. Three Delphi rounds were conducted to reach consensus. Questionnaires were sent electronically to panel members and comments about each question were solicited.

Results

Eight recommendations were formulated regarding regulation, pharmacovigilance, risk management, naming, traceability, registries, economic aspects, and biomimics.

Conclusion

The recommendations highlighted that, after receiving regulatory approval, pharmacovigilance is a fundamental strategy to ensure safety of all medications. Registries should be employed to monitor use of biosimilars and to identify potential adverse effects. The price of biosimilars should be significantly lower than that of reference products to enhance patient access. Biomimics are not biosimilars and, if they are to be marketed, they must first be evaluated and approved according to established regulatory pathways for novel biopharmaceuticals.

Key Points

• Biologics have improved the treatment of rheumatic diseases.

• Their high cost limits access for many patients in both North America and Latin America.

• Biosimilars typically are less expensive, providing additional treatment options for patients with rheumatic diseases.

• PANLAR presents its consensus on biosimilars in rheumatology

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Biologics have improved the treatment of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs), preventing joint damage and resulting in better outcomes. In several previous publications, the Pan American League of Associations of Rheumatology (PANLAR) has discussed the advances in the use of biological therapies to treat RMDs in Latin America (LA) [1,2,3]. LA has a heterogeneous population estimated at 577 million people, with diverse healthcare systems and different levels of access, ranging from those that provide broad coverage to those in which individuals have to pay out-of-pocket for medical expenditures [4,5,6]. Following patent expiration for biologicals, biosimilars, which typically are less expensive due to lower development costs, have the potential to increase patient access to these very effective medications, and thereby may provide additional treatment options for patients with rheumatic diseases [7,8,9,10].

A biosimilar is a biological product that is “highly similar” to an existing approved reference product and has “no clinically meaningful differences” [11]. Biosimilars are equivalent in efficacy and comparable in safety to their reference biologics. However, unlike small-molecule generic drugs for which the active chemical substance is synthesized to be identical to that of the reference small molecule drug, biosimilars usually are not identical to their reference products because these complex molecules are manufactured in living cells by a process that is more complex than that for small-molecule drugs [12, 13]. Another drug category, the biomimics, also known as “intended copies,” are replicas of approved biologic drugs that had received marketing approval without adhering to the international standards for evaluation and approval of biosimilars. Biomimics of etanercept and rituximab are currently available in some Asian and Latin American countries [14]. Considering the evolving state of biologics, biosimilars, and biomimics in the Americas and the inconsistency of regulations regarding biosimilars among LA countries, PANLAR has created a consensus statement on biosimilars in rheumatology.

Methods

This consensus statement was intended for a target audience of rheumatologists and other healthcare providers, regulators, legislators, and patients. The consensus process was developed by four groups: the PANLAR steering committee, the scientific committee, panel members, and an external review panel. The steering committee was comprised of three representatives of PANLAR (the PANLAR president, a PANLAR education and scientific committee officer, and a rheumatologist). PANLAR selected members of the scientific committee to develop the consensus, based on professional experience in rheumatology, expertise in pharmacologic therapies for rheumatic diseases and in biosimilars, and disclosure of conflicts of interest (COI) supported by the conflict of interest form of the Health and Care Excellence, NICE, on which the members declared the absence of COI. This scientific committee consisted of two rheumatologists (one with expertise in clinical epidemiology and guidelines development), and one epidemiologist. The scientific committee had complete independence to develop the consensus statement, since PANLAR was the sole supporter of this project with no funding from or participation by the pharmaceutical industry. The consensus process development was guided by the GIN-McMaster Guideline Development Checklist [15]. This checklist contains 18 topics and 146 items, as well as a webpage to facilitate its use by guideline developers to ensure that no key steps are missed [15]. All steps in the development of the PANLAR consensus on biosimilars were documented to ensure transparency and traceability. A modified Delphi process, in which participants’ answers are analyzed anonymously, was chosen for development of the consensus statement [16]. Using this approach, it is possible for many participants to express opinions freely and confidentially with a low probability of a convener or moderator introducing bias. Additionally, this methodology allows Internet-based voting, making it convenient, cost-effective, and not limited by geographic diversity [16].

Panel member selection

The scientific committee and the PANLAR steering committee used the following criteria to select panel members: expertise on pharmacologic therapies for rheumatic diseases and on biosimilars, teaching and research experience, and potential COI, disclosed using a standard form. Each PANLAR member national society, college, or association nominated three candidates, and PANLAR selected one candidate from each of its four geographical regions (North, Central, Bolivarian, and Southern region). During a web-based conference, the curriculum vitae and COI declaration of each candidate was reviewed by members of the steering and scientific committees and the panel members were chosen. This meeting was recorded digitally to ensure transparency throughout the process. One panel member was chosen from each of the 21 PANLAR member-countries and 4 members were appointed by PANLAR from each of the four geographical regions, for a total of 25 panel members. The external review panel consisted of six experts in biosimilars, selected by PANLAR and the scientific committee. This external review panel was responsible for reviewing the questions or solving any other issues that might arise during the consensus development process.

The PANLAR steering committee defined the following topics as priorities to be explored during the consensus: regulation, efficacy and safety, extrapolation of indications, interchangeability, automatic substitution, pharmacovigilance, risk management, naming, traceability, registries, economic aspects, and biomimics. Questionnaires were developed to address each of these topics, using a five-point Likert scale for responses (1 completely disagree–5 completely agree). The steering committee anticipated that three Delphi rounds would be sufficient to reach consensus. Consensus was achieved when there was agreement among 80% or more of panel members. Questions for which consensus was not reached were reformulated and circulated in subsequent Delphi rounds until consensus was reached. If consensus was not achieved after the third round, those questions were excluded for further consideration [17].

Comprehensive literature review

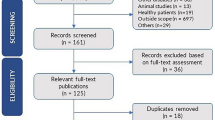

A comprehensive literature review was conducted in June 2017. MEDLINE via PubMed was the database consulted according to the following Mesh terms:

-

“Biosimilar Pharmaceuticals”[Mesh]

-

(“Patient Safety”[Mesh]) AND “Biosimilar Pharmaceuticals”[Mesh]

-

(“Economics, Pharmaceutical”[Mesh]) AND “Biosimilar Pharmaceuticals”[Mesh]

-

(“Pharmacovigilance”[Mesh]) AND “Biosimilar Pharmaceuticals”[Mesh]

-

“Biosimilar Pharmaceuticals”[Mesh] AND Immunogenicity [All Fields]

-

(“Therapeutic Equivalency”[Mesh]) AND “Biosimilar Pharmaceuticals”[Mesh]

-

(“Drug and Narcotic Control”[Mesh]) AND “Biosimilar Pharmaceuticals”[Mesh]

-

(“Forecasting”[Mesh]) AND “Biosimilar Pharmaceuticals”[Mesh]

This literature search yielded 226 publications related to the research question of comparative effectiveness and safety of biosimilars with their reference products in patients with rheumatic diseases. Of these, 108 articles were selected and classified into the following topics: extrapolation of indications, safety, regulation, interchangeability, pharmacovigilance, immunogenicity, and pharmacoeconomic. These articles were sent to the panelists with the first version of the questionnaire.

Questionnaires

Following a comprehensive literature review and considering the heterogeneity of the panel members (language, culture, national healthcare system, and expertise on biosimilars), the scientific committee designed the first questionnaire (Q1). This questionnaire consisted of 22 questions with 44 possible answers and free space for comments. The objective was to assess the knowledge of the panel members regarding the concept of biosimilars, regulation, and safety. Q1 was circulated via email and all answers were analyzed anonymously. After the first Delphi round, panel members met face-to face in September 2017 at the II PANLAR Review Course in Rheumatology-Biosimilars update in Lima, Peru. At this meeting, panel members discussed a variety of topics related to the regulatory approval and use of biosimilars and biomimics. During this meeting, a second questionnaire (Q2) containing 15 questions on topics about which consensus was not achieved during the first round was circulated to the panel members.

The topic of biomimics was included in a third questionnaire (Q3) since, during the meeting in Lima, panel members had indicated that it was a fundamental topic. Q3 consisted of 12 questions related to nomenclature, safety and efficacy, traceability, pharmacovigilance, extrapolation of indications, automatic substitution, and economic aspects. After review by the steering and scientific committees, Q3 was circulated to the panel members. The third Delphi round was conducted according to the same procedure as was used in the previous Delphi rounds.

Results

The results of each round of discussion are presented below (Table 1).

All answers for which there was agreement among 80% or more of panel members were considered to have reached consensus. After the first round, consensus was achieved regarding definitions, production, comparability, regulation, immunogenicity, interchangeability ,and the scientific rationale for the extrapolation of indications (detailed information in Appendix. Those topics about which consensus was not achieved were automatic substitution, switching, and economic aspects. Based on the responses and comments during the first round, the second questionnaire (Q2) was designed. Of the 15 questions and 23 possible answers included in Q2, consensus was achieved for 9 of the answers (39%). The topics for which consensus was not achieved in Q2 were safety and efficacy, economic aspects, extrapolation of indications, and automatic substitution. A third questionnaire (Q3) was then created to address the issues not resolved by Q2. Q3 included 12 questions with 22 possible answers. Consensus was achieved for 7 of the answers (31%) addressing the topics of regulation, pharmacovigilance, risk management, traceability, naming, registries, economic aspects, and biomimics. Consensus could not be achieved on the remaining 15 answers about extrapolation of indications, switching, and automatic substitution; these topics were then excluded for further discussion and were not addressed in the PANLAR consensus statement on biosimilars.

PANLAR position

The position of PANLAR regarding biosimilars, based on the consensus process, is presented and discussed below (Table 2):

-

1.

Biosimilars should be considered as a treatment option for patients with rheumatic diseases.

Biosimilarity indicates that there are no clinically significant differences between a biosimilar that has been approved by a regulatory body in a highly regulated area and its reference product in terms of safety, quality, and efficacy. The determination of biosimilarity includes extensive analytical studies comparing a proposed biosimilar to its reference product and assessment of pharmacokinetic (PK)/pharmacodynamic (PD) parameters and efficacy in comparative clinical studies to establish equivalent efficacy and comparable safety and immunogenicity of the proposed biosimilar to its reference product [18].

-

2.

Post-marketing pharmacovigilance programs should be implemented to identify and assess any potential safety issues related to the use of biosimilars.

Pharmacovigilance is fundamental to monitoring the safety and efficacy of any drug and must be implemented following the approval and marketing of biosimilars [19]. The United States Food & Drug Administration (FDA) and Health Canada have spontaneous adverse event reporting systems. However, few countries in LA have adequate post-marketing monitoring systems in place. To complicate matters, in most Latin American countries, there are several different agencies or organizations that receive adverse event reports, and these do not always communicate with one another [20]. It is necessary to implement a centralized system to collect pharmacovigilance data, thereby optimizing the analysis and interpretation of these data [21]. The Americas Health Foundation (AHF) convened a meeting of experts from LA to address the gaps between national biologics registries and national surveillance agencies dealing with biosimilars [20]. The group discussed with policymakers its recommendations to implement a pharmacovigilance system [20]. They defined that the key goals of the system should be to identify patients receiving the drug, to monitor these patients over time for adverse reactions and the effectiveness of the biosimilar, and to collect data about efficacy in indications for which the biosimilar was not studied in clinical trials and therapeutic substitution. PANLAR should monitor these pharmacovigilance initiatives and ensure that they are maintained.

-

3.

A risk management plan (RMP) for approved biosimilars should be required by regulatory agencies. The RMP for a biosimilar should be the same as that for its reference product.

A comprehensive system for surveillance of adverse events associated with both originator biologics and biosimilars would provide evidence to reduce skepticism and uncertainty among prescribers regarding the use of biosimilars. The EMA and the FDA each requires RMPs of both originator biologics and biosimilars. These RMPs mandate post-marketing monitoring of the safety and efficacy of approved biosimilars [12, 22]. Similar RMPs are not yet required by regulatory agencies in all Latin American countries.

-

4.

The implementation of registries is encouraged to supplement post-approval surveillance for safety concerns related to biosimilars.

Registries are designed to gather population-based data systematically about the clinical presentation and treatment of diseases, including the nature and frequency of adverse events, to supplement data collected in clinical trials [23]. The Spanish Society of Rheumatology launched the BIOBADASER (registry) in 2000 to identify and estimate the risk of adverse events occurring during the conduct of clinical practice and to assess the long-term retention of treatment with biologic agents [24]. In 2007, with sponsorship from PANLAR, several Latin American countries formed the BIOBADAMERICA collaboration to reproduce the BIOBADASER registry in their respective countries [24]. In the USA, the American College of Rheumatology launched the RISE registry in 2014, in which data are extracted from electronic medical records used by rheumatology practices. However, challenges remain in implementing post-approval surveillance in countries that lack registries or that fail to maintain and update their existing registries [25].

-

5.

A naming convention should be implemented to clearly identify and distinguish a specific product (biosimilar or reference biologics).

Naming is crucial to track medications for proper pharmacovigilance [26]. In the USA, the FDA has specified that biosimilars should have unique nonproprietary names that are distinguished from those of their reference products by four-letter suffices which are devoid of meaning [27]. In Mexico, Colombia, Argentina, Brazil, and Chile, there is no nonproprietary naming convention to distinguish biosimilars from their reference products [28]. The World Health Organization recommends that the standard international nonproprietary name (INN) system be used for biosimilars to enable easy recognition of the active ingredient [29]. This system is employed in the European Union (EU), where a biosimilar has the same INN as its reference product [30]. Thus, in the EU, a biosimilar may be distinguished from its reference product only by its different proprietary (brand) name. However, the policy of using the same nonproprietary name for both a biosimilar and its reference product poses challenges regarding traceability and pharmacovigilance (safety assessments) unless the brand names remain consistent and are always used [31]. EU legislation requires that, for all reports of adverse drug reactions, all appropriate measures should be taken to identify the brand name and lot number of the drug, as well as the INN [32].

-

6.

Strategies to ensure traceability should be implemented to follow all steps involved in the supply chain, enabling association of adverse effects with a specific medication.

Other than in the USA, where no biosimilar has yet been approved as being “interchangeable,” it is expected that biosimilars and reference products may be substituted back and forth repeatedly as will biosimilars of the same reference product. Thus, there will be a need to track and document which products a patient receives [22]. In the USA, this could be done by using the nonproprietary name that includes a unique four-letter suffix. However, this will be challenging in LA because of the huge differences in national healthcare systems, cultures, and socio-economic status. Thus, different strategies should be developed and implemented in each country in accordance with regional needs and available resources.

-

7.

The price of biosimilars should be significantly lower than that of their reference products, potentially increasing access to expensive medications used to treat rheumatic diseases.

If priced significantly lower than their reference products, biosimilars should enhance access to these biologic medications. Some studies suggest that biosimilars exert downward pressure on pricing [33]. In Central and Eastern Europe, the introduction of CT-P13 resulted in a 20–60% reduction in the cost of infliximab. In 2015 in Norway, where there is a single payer and a “winner-takes-all” bidding process, CT-P13 was priced 69% lower than reference infliximab [34, 35]. Studies have estimated that the potential savings in the USA from using biosimilars over a 10-year period could range between USD $25 billion and USD $100 billion [36]. In Chile, Brazil, and Mexico, biosimilars are priced 20 to 35% lower than their reference biologics in [28]. Mestre-Ferrandiz and colleagues suggested that, as physicians become more confident about the data supporting interchangeability between biosimilars and their reference products, the prices could decrease, provided that incentives are in place for both payers and patients to benefit from price competition [37]. They highlighted that initiatives focusing on short-term savings (price cuts for originators, reference pricing or substitution rules (without outcomes data) could put the opportunity to create a more competitive market at risk [37] .

-

8.

Biomimics (“intended copies,” replicas of biologics that have not been reviewed or approved according to international guidelines provided by the WHO for biosimilar approval) cannot be considered to be biosimilars. Therefore, PANLAR does not recommend their use.

Few data are available regarding the efficacy and safety of biomimics. These drugs have neither been reviewed nor approved by a regulatory agency according to a pathway for approval of biosimilars. Biomimics may differ from originator biologics in their primary structure, dosage, and formulation, which may result in clinically significant differences in efficacy or safety, with the potential to compromise patient care [38]. In Mexico, where biomimics are marketed, there has been automatic substitution by pharmacies of etanercept and rituximab biomimics for the originator products [39]. The lack of adequate post-marketing surveillance programs in some countries, where biomimics are substituted for originator biopharmaceuticasls in an unregulated manner, puts patients at risk for adverse outcomes.

Discussion

Biologics have improved the long-term outcome of a variety of inflammatory diseases. However, some Latin American countries spend a significant portion of their healthcare budget on biologics, which comprise less than 3% of drug prescriptions [40]. As patents for some biologics have expired or will soon expire, the availability of lower-cost biosimilars has introduced competition to the market for biologics used to treat chronic inflammatory diseases [39]. Thus, PANLAR organized a consensus process to develop a consensus statement to guide its members in the use of biosimilars. There was consensus among panel members regarding definitions, basic concepts, and scientific methods used in the regulatory process to evaluate biosimilars. Most of the participants agreed about the basic concepts of quality, safety, and biosimilarity. Since biosimilars have come to market only recently in the Americas, some topics remained controversial among panel members and are not yet harmonized across all regulatory agencies, such as nomenclature, extrapolation of approval to indications in which the biosimilar has not been evaluated in clinical trials, and automatic substitution [28]. There is a need for “real world” outcomes data, such as that about the consequences of changing (transitioning) from a biologic to its biosimilar, to assist healthcare providers in evaluating biosimilars.

No consensus was achieved regarding extrapolation of indications. Some regulatory agencies suggest that decisions regarding extrapolation of indications should be made on an indication-by-indication basis. In Canada, for example, the biosimilar infliximab-dyyb (Inflectra®) was approved in 2014 to treat rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, in which it had been studied, and, by extrapolation, to treat plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Initially, because of differences between the biosimilar and its reference product in glycosylation and in antibody-dependent cell mediated cytotoxicity, Health Canada denied extrapolation of approval to the indications of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. However, in 2016, Health Canada granted the biosimilar infliximab-dyyb approval to treat Crohn’s disease, fistulizing Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis based on similarity between the biosimilar and its reference product in quality, mechanism of action, and safety profile, and on accumulated clinical experience with the reference product [41].

The panel members also did not reach consensus about automatic substitution (the practice of dispensing an equivalent interchangeable medication at the pharmacy level, without consulting the prescribing healthcare provider, instead of that which had been prescribed) [42]. Although the panel members agreed on the definition of interchangeability, the difference of opinion centered around substitution without the prescriber’s authorization. Many details still need to be elucidated. What will be required to grant the designation of “interchangeable”? How many switches between reference product and biosimilar will be required in clinical trials? Will all regulatory agencies require PK and PD parameters as primary outcome measures? What role, if any, will drug delivery devices play in the determination of interchangeability? We anticipate that multiple switches between biosimilars and their reference products and among different biosimilars of the same reference product are likely to occur to contain drug costs in Latin American markets. The absence of an ideal pharmacovigilance system in some countries will impede the post-marketing assessment of efficacy and adverse events associated with the prescribed biosimilar [20]. Also, healthcare providers are unlikely to agree with substitution without their explicit authorization.

The nocebo effect has contributed significantly to discontinuation of treatment with a biosimilar by patients in some European countries who had undergone nonmedical switching from a biologic agent to which they had been responding. The EMA guidance on substitution of a reference biologic with a biosimilar asserts that oversight of such substitution is the responsibility of individual European Union member states and should occur only under the direction of a healthcare professional [43] [44]. In most European countries (including Italy, Spain, the UK, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Germany), automatic substitution is either discouraged or not allowed [37]. In other countries, such as Australia, substitution of biosimilars for their reference products takes place with certain exemptions [45]. Should automatic substitution be adopted in LA? Regardless, the question remains: shall we strengthen pharmacovigilance, as has occurred in many European countries in which nationwide mandatory switches are ongoing, or do such switches violate the principle of shared decision-making?

An important topic added to the third questionnaire was that of biomimics (or “intended copies”), which are replicas of biologic agents that have not been reviewed by a regulatory agency according to a pathway for biosimilar approval yet are marketed in several Latin American countries [39]. Most panel members agreed that all biomimics should be required to demonstrate efficacy and safety in well-designed comparative effectiveness clinical trials and be subject to regulatory review according to the pathway for biosimilar approval recommended by the WHO so that, if approved, they could be considered to be true biosimilars. Similar recommendations have been proposed by a group of experts from LA [46]. However, if a biomimic fails to meet analytical criteria for biosimilarity, it should not be considered to be a biosimilar and should be required to undergo evaluation as a novel biologic. The issues surrounding biomimics are an important agenda item to be discussed among PANLAR members so as to develop national policies that harmonize regulation of biomimics across all Latin American countries.

This consensus statement has strengths, such as the independence of the Scientific Committee and the project’s complete funding by PANLAR, making external funding sources unnecessary. The declaration and management of conflicts of interest during the panel members’ selection ensured transparency for the process. All steps of the consensus process were planned, implemented, and documented following the GIN-McMaster Checklist guidance [15]. The modified Delphi approach using online voting was appropriate, considering the geographical distribution of participants from throughout LA and North America. Panel members had the opportunity to articulate their opinions in the online questionnaires and to suggest inclusion of positions for further discussion at the face-to face meeting that took place in Lima.

However, there are also potential weaknesses to this process, such as differing levels of knowledge about and experience with biosimilars among the panel members. Also, because the Steering Committee and panel members were chosen to represent a variety of geographical regions with diverse healthcare systems and regulations regarding drug approval, it might have been more difficult to reach consensus. However, when agreement on a topic was achieved, it exemplified valid consensus.

Following publication of this consensus statement, the next steps will be to disseminate them through a variety of media and to educate healthcare providers, patients, caregivers, and policymakers about biosimilars. By doing so, a larger number of healthcare professionals and patients will become familiar with the topic of biosimilars and should more readily accept their use in clinical practice. The II PANLAR Review Course in Rheumatology (Lima) was a successful example of an educational program in which experts on biosimilars presented information about a variety of topics, enhancing participants’ knowledge about biosimilars. Additional and extensive dissemination of information about biosimilars throughout LA and North America should help both patients and healthcare providers to better understand this topic, facilitating shared decision-making and thereby increasing acceptance of biosimilars. With their increased market penetrance, biosimilars should increase market competition, driving down the high cost of biologic agents and thereby increasing access to these effective treatments for rheumatologic and other inflammatory diseases. PANLAR plans to update these recommendations in 2 years.

Conclusions

Given the lack of harmonized regulations regarding biosimilars in LA and North America, this paper proposes consensus recommendations based on established international guidelines to be followed by the various stakeholders who care for patients with rheumatologic diseases. The participants in this consensus statement acknowledged that standardization of nomenclature to ensure traceability, establishment of an effective pharmacovigilance system for surveillance of adverse events, and implementation of appropriate risk management plans should provide for comprehensive monitoring of the use of biosimilars. It is essential that healthcare providers and patients actively collaborate to generate “real world” data in registries to provide ongoing assessment of biosimilar use. Dissemination of this consensus statement through educational programs can help patients, healthcare professionals, and policymakers to better understand the development and incorporation of biosimilars into clinical practice. Further discussion among these stakeholders should address unresolved issues such as the potential consequences of multiple switches, automatic substitution (provided that interchangeability has been demonstrated), and extrapolation of indications. The results of this consensus statement should facilitate access to biologic therapies for rheumatologic diseases by promoting the use of high-quality biosimilar medications at competitive prices.

Change history

20 May 2019

The two co-authors of the mentioned above article were incorrect. The correct are authors should have been “P. A. Beltrán” instead of “P. A. B. Roa” and “J. F. Diaz-Coto” instead of “L. Diaz Soto”.

References

Cardiel MH (2006) First Latin American position paper on the pharmacological treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 45(Suppl 2):ii7–ii22. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kei500

Soriano ER, Galarza-Maldonado C, Cardiel MH, Pons-Estel BA, Massardo L, Caballero-Uribe CV, Achurra-Castillo AF, Barile-Fabris LA, Chavez-Corrales J, Diaz-Coto JF, Esteva-Spinetti MH, Guibert-Toledano M, Palazuelos FI, Keiserman MW, Lomonte AV, Mota LM, Pineda Villasenor C, Alarcon GS (2008) Use of rituximab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: the Latin American context. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 47(7):1097–1099. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ken015a

Massardo L, Suarez-Almazor ME, Cardiel MH, Nava A, Levy RA, Laurindo I, Soriano ER, Acevedo-Vazquez E, Millan A, Pineda-Villasenor C, Galarza-Maldonado C, Caballero-Uribe CV, Espinosa-Morales R, Pons-Estel BA (2009) Management of patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Latin America: a consensus position paper from Pan-American League of Associations of Rheumatology and Grupo Latino Americano De Estudio De Artritis Reumatoide. J Clin Rheumatol : practical reports on rheumatic & musculoskeletal diseases 15(4):203–210. https://doi.org/10.1097/RHU.0b013e3181a90cd8

Al Maini M, Adelowo F, Al Saleh J, Al Weshahi Y, Burmester GR, Cutolo M, Flood J, March L, McDonald-Blumer H, Pile K, Pineda C, Thorne C, Kvien TK (2015) The global challenges and opportunities in the practice of rheumatology: white paper by the World Forum on Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases. Clin Rheumatol 34(5):819–829. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-014-2841-6

Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M et al (2012) Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet (London, England) 380(9859):2163–2196. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61729-2

Burgos-Vargas R, Catoggio LJ, Galarza-Maldonado C, Ostojich K, Cardiel MH (2013) Current therapies in rheumatoid arthritis: a Latin American perspective. Reumatologia Clinica 9(2):106–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reuma.2012.09.001

Alvarez-Hernandez E, Pelaez-Ballestas I, Boonen A, Vazquez-Mellado J, Hernandez-Garduno A, Rivera FC, Teran-Estrada L, Ventura-Rios L, Ramos-Remus C, Skinner-Taylor C, Goycochea-Robles MV, Bernard-Medina AG, Burgos-Vargas R (2012) Catastrophic health expenses and impoverishment of households of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Reumatologia Clinica 8(4):168–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reuma.2012.05.002

Mody GM, Brooks PM (2012) Improving musculoskeletal health: global issues. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 26(2):237–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2012.03.002

Castaneda-Hernandez G, Szekanecz Z, Mysler E, Azevedo VF, Guzman R, Gutierrez M, Rodriguez W, Karateev D (2014) Biopharmaceuticals for rheumatic diseases in Latin America, Europe, Russia, and India: innovators, biosimilars, and intended copies. Joint Bone Spine : revue du rhumatisme 81(6):471–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2014.03.019

Moorkens E, Jonker-Exler C, Huys I, Declerck P, Simoens S, Vulto AG (2016) Overcoming barriers to the market access of biosimilars in the European Union: the case of biosimilar monoclonal antibodies. Front Pharmacol 7:193. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2016.00193

FDA (2017) Biosimilar and Interchangeable Products. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/TherapeuticBiologicApplications/Biosimilars/ucm580419.htm. Accessed 31/03/2018 2018

EMA (2017) Biosimilars in the EU Information guide for healthcare professionals. https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/leaflet/biosimilars-eu-information-guide-healthcare-professionals_en.pdf. Accessed 31/03/2018 2018

Kay J (2011) Biosimilars: a regulatory perspective from America. Arthritis Res Ther 13(3):112. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar3310

Castaneda-Hernandez G, Gonzalez-Ramirez R, Kay J, Scheinberg MA (2015) Biosimilars in rheumatology: what the clinician should know. RMD open 1(1):e000010. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2014-000010

Schunemann HJ, Wiercioch W, Etxeandia I, Falavigna M, Santesso N, Mustafa R, Ventresca M, Brignardello-Petersen R, Laisaar KT, Kowalski S, Baldeh T, Zhang Y, Raid U, Neumann I, Norris SL, Thornton J, Harbour R, Treweek S, Guyatt G, Alonso-Coello P, Reinap M, Brozek J, Oxman A, Akl EA (2014) Guidelines 2.0: systematic development of a comprehensive checklist for a successful guideline enterprise. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l’Association medicale canadienne 186(3):E123–E142. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.131237

Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H (2000) Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs 32(4):1008–1015

Nair R, Aggarwal R, Khanna D (2011) Methods of formal consensus in classification/diagnostic criteria and guideline development. Semin Arthritis Rheum 41(2):95–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2010.12.001

Pineda C, Castaneda Hernandez G, Jacobs IA, Alvarez DF, Carini C (2016) Assessing the immunogenicity of biopharmaceuticals. BioDrugs : clinical immunotherapeutics, biopharmaceuticals and gene therapy 30(3):195–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-016-0174-5

Azevedo VF, Meirelles Ede S, Kochen Jde A, Medeiros AC, Miszputen SJ, Teixeira FV, Damiao AO, Kotze PG, Romiti R, Arnone M, Magalhaes RF, Maia CP, de Carvalho AV (2015) Recommendations on the use of biosimilars by the Brazilian Society of Rheumatology, Brazilian Society of Dermatology, Brazilian Federation of Gastroenterology and Brazilian Study Group on Inflammatory Bowel Disease—focus on clinical evaluation of monoclonal antibodies and fusion proteins used in the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev 14(9):769–773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2015.04.014

Pineda C, Caballero-Uribe CV, de Oliveira MG, Lipszyc PS, Lopez JJ, Mataos Moreira MM, Azevedo VF (2015) Recommendations on how to ensure the safety and effectiveness of biosimilars in Latin America: a point of view. Clin Rheumatol 34(4):635–640. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-015-2887-0

Mysler E, Scheinberg M (2012) Biosimilars in rheumatology: a view from Latin America. Clin Rheumatol 31(9):1279–1280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-012-2068-3

Dorner T, Strand V, Cornes P, Goncalves J, Gulacsi L, Kay J, Kvien TK, Smolen J, Tanaka Y, Burmester GR (2016) The changing landscape of biosimilars in rheumatology. Ann Rheum Dis 75(6):974–982. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209166

Mysler E, Pineda C, Horiuchi T, Singh E, Mahgoub E, Coindreau J, Jacobs I (2016) Clinical and regulatory perspectives on biosimilar therapies and intended copies of biologics in rheumatology. Rheumatol Int 36(5):613–625. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-016-3444-0

Carmona L, de la Vega M, Ranza R, Casado G, Titton DC, Descalzo MA, Gomez-Reino J (2014) BIOBADASER, BIOBADAMERICA, and BIOBADADERM: safety registers sharing commonalities across diseases and countries. Clin Exp Rheumatol 32(5 Suppl 85):S-163–S-167

de la Vega M, da Silveira de Carvalho HM, Ventura Rios L, Goycochea Robles MV, Casado GC (2013) The importance of rheumatology biologic registries in Latin America. Rheumatol Int 33(4):827–835. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-012-2610-2

FDA (2017) Nonproprietary naming of biological products. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidances/ucm459987.pdf. Accessed 31/03/2018 2018

FDA (2107) Guidance compliance regulatory information. www.fda.gov/guidances/ucm459987.pdf. Accessed 31/03/2018 2018

de la Cruz C, de Carvalho AV, Dorantes GL, Londono Garcia AM, Gonzalez C, Maskin M, Podoswa N, Redfern JS, Valenzuela F, van der Walt J, Romiti R (2017) Biosimilars in psoriasis: clinical practice and regulatory perspectives in Latin America. J Dermatol 44(1):3–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.13512

OMS (2006) WHO informal consultation on interna tional nonproprietary names (INN) policy for biosimilar products https://www.who.int/medicines/services/inn/BiosimilarsINN_Report.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 31/03/2018 2018

EMA (2012) Questions and answers on biosimilar medicines (similar biological medicinal products). https://www.medicinesforeurope.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/WC500020062.pdf. Accessed 31/03/2018 2017

Vermeer NS, Spierings I, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK, Straus SM, Giezen TJ, Leufkens HG, Egberts TC, De Bruin ML (2015) Traceability of biologicals: present challenges in pharmacovigilance. Expert Opin Drug Saf 14(1):63–72. https://doi.org/10.1517/14740338.2015.972362

Calvo B, Zuniga L (2014) EU’s new pharmacovigilance legislation: considerations for biosimilars. Drug Saf 37(1):9–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-013-0121-z

Brodszky V, Baji P, Balogh O, Pentek M (2014) Budget impact analysis of biosimilar infliximab (CT-P13) for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in six Central and Eastern European countries. Eur J Health Econ : HEPAC : health economics in prevention and care 15(Suppl 1):S65–S71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-014-0595-3

Braun J, Kudrin A (2016) Switching to biosimilar infliximab (CT-P13): evidence of clinical safety, effectiveness and impact on public health. Biologicals : journal of the International Association of Biological Standardization 44(4):257–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biologicals.2016.03.006

GABI GaBI (2015) Huge discount on biosimilar infliximab in Norway http://www.gabionline.net/Biosimilars/General/Huge-discount-on-biosimilar-infliximab-in-Norway. Accessed 31/03/2018 2018

A A, R K, R B (2007) Modeling federal cost savings of follow-on biologics. https://avalere.com/research/docs/Follow_on_Biologic_Modeling_Framework.pdf. Accessed 31/03/2018 2018

Mestre-Ferrandiz J, Towse A, Berdud M (2016) Biosimilars: how can payers get long-term savings? PharmacoEconomics 34(6):609–616. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-015-0380-x

Azevedo V, Hassett B, Fonseca JE, Atsumi T, Coindreau J, Jacobs I, Mahgoub E, O’Brien J, Singh E, Vicik S, Fitzpatrick B (2016) Differentiating biosimilarity and comparability in biotherapeutics. Clin Rheumatol 35(12):2877–2886. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-016-3427-2

Scheinberg M, Castaneda-Hernandez G (2014) Anti-tumor necrosis factor patent expiration and the risks of biocopies in clinical practice. Arthritis Res Ther 16(6):501. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-014-0501-5

Miguel F, Areli L, Gabriel M, Patrick R (2013) Unfolding the biosimilar landscape in Latin America. http://www.pmlive.com/pharma_intelligence/unfolding_the_biosimilar_landscape_in_latin_america_470137. Accessed 31/03/2018 2018

PFIZER (2016) Health Canada approves Inflectra® (biosimilar infliximab) for three additional indications: Crohn’s disease, fistulizing Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. https://www.pfizer.ca/node/1731. Accessed 31/03/2018 2018

Ebbers HC, Chamberlain P (2014) Interchangeability. An insurmountable fifth hurdle? Gen Biosimilars Initiat J (GaBI Journal) 3:88–93. https://doi.org/10.5639/gabij.2014.0302.022

Kvien TK (2017) Switching from originator product to biosimilars in rheumatology, dermatology and gastroenterology: clinical evidence. http://gabi-journal.net/wp-content/uploads/Kvien-GCC-V18A05LB.pdf. Accessed 31/03/2018 2018

EMA (2014) Guideline on similar biological medicinal products containing biotechnology -derived proteins as active substance: quality issues. https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-similar-biological-medicinal-products-containing-biotechnology-derived-proteins-active_en-0.pdf. Accessed 31/03/2018 2018

WHO (2016) WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization. https://www.who.int/biologicals/expert_committee/WHO_TRS_999_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 31/03/2018 2018

Azevedo V, Mysler E, Aceituno A, Hughes J, Flores-Murrieta F, Ruiz de Castilla EM (2014) Recommendations for the regulation of biosimilars and their implementation in Latin America, vol 3. doi:https://doi.org/10.5639/gabij.2014.0303.032, 3, 148

Funding

This work was supported by the Pan-American League of Associations for Rheumatology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SK, JB, PB, CG, CVC, ES, CP, and VF designed and conceived the study. JB and PB developed search strategies, provided workflow suggestions, conducted the literature review, and analyzed the data. SK, JB, PB, EM, and JK wrote and revised the manuscript. PANLAR provided key institutional support and funding. All authors participated in the consensus development process, read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Definitions accepted by consensus

-

1.

What are biological drugs? Biological drugs are made up of proteins such as hormones (growth hormones, insulin, erythropoietin), human body naturally produced enzymes or monoclonal antibodies, but also of blood products, immunological medicines (such as serum and vaccines), allergens, and technological products (like gene and cell therapy products).

-

2.

How are biological drugs produced? These products are obtained by methods which include, but are not limited to, human or animal origin cell cultures, culture and propagation of microorganisms and viruses, processing from human or animal biological tissues or fluids, transgenesis, Deoxyribonucleic Acid techniques (DNA), and hybridoma techniques.

-

3.

What are biosimilar medications? They are biotech products that have been proven to be comparable to a reference product that has already been quality approved, non-clinical and clinical assessment through studies with adequate methodology in each case.

-

4.

How are biosimilar drugs differentiated from generic small molecule chemical drugs? In manufacturing techniques, their size and molecular complexity or their stability. Small molecule drugs are usually manufactured by chemical synthesis, while most biosimilar products are manufactured with living systems such as microorganisms and animal cells and are purified by a complex manufacturing process. Small molecule drugs usually have well-defined chemical structures and can often be analyzed to determine their various components. However, this is not the case for biosimilars, whose inherent molecular variability makes them harder to characterize than small molecule drugs.

-

5.

What is a biological reference product? It is an innovative biological drug, which has been authorized for the first time for clinical use.

-

6.

What is comparability? The systematic process leading to conclude that products have very similar quality attributes before and after changes in the manufacturing process have taken place and that no adverse impact on the safety or efficacy, including immunogenicity, of the drug has occurred. In some cases, non-clinical or clinical data may contribute to the conclusion.

-

7.

What is biosimilarity? It is a demonstration of the absence of clinically significant biosimilar differences with respect to the reference biological drug, which should be confirmed with appropriate clinical studies. Likewise, rigorous and extensive analytical assessments are the basis of the similarity assessment. It means that a biosimilar is “very similar” to the biological reference despite minor differences in clinically inactive components and that there are no clinically significant differences between them in terms of safety, purity, and potency of the product.

-

8.

What is interchangeability? It is a property where it is possible to change a biosimilar for a reference product or vice versa without adding risk or decreasing effectiveness for patients. In general, interchangeability assumes that in controlled patients it is possible to switch from one product to another without alterations in safety and efficacy.

-

9.

What is automatic replacement? It is a situation where a distributor decides to change one product for another, often due to cost related issues. There must be at least the guarantee that the products are interchangeable; these changes are made at the pharmacy without the authorization of the prescriber.

-

10.

What scientific rationale underlies the approval of biosimilar drugs? Demonstration of the absence of clinically significant differences with regards to the reference biological drug, to be confirmed with appropriate clinical studies. In addition, rigorous and extensive analytical assessments are the basis of the similarity assessment.

-

11.

What assessment should be performed for the approval of a biosimilar? Submitting the results of a comparability analysis between the biosimilar and the reference biological drug. This comparability analysis should include: (A) Quality comparability: physical-chemical and biological comparability. (B) Non-clinical comparability: non-clinical comparative studies. (C) Clinical comparability: comparative clinical studies, including immunogenicity studies. Ensuring that there are no clinically significant differences between the proposed biosimilar and the reference biological drug in terms of safety, quality and efficacy. This includes a specific clinical program that contains comparative studies of PK, PD, efficacy, and safety (including immunogenicity) adequate for establishing equivalence to the originating product as a comparator in pre-regulatory testing.

-

12.

What is extrapolation? It is the process by which regulatory approval of the biosimilar drug is allowed for the treatment of diseases that have not been specifically studied during the clinical development of the disease such approval is possible only if its biosimilarity has been demonstrated and if the mechanism of action is the same among the different indications to extrapolate.

-

13.

What is the scientific rationale for the extrapolation of indications? It requires to adequately consider:

-

That the mechanisms of action are the same and reasonably understood.

-

That comparative clinical tests have been performed in the most sensitive environment(s) with potential differences in safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity.

-

The differences in the risk-benefit balance between the studied and non-studied indications.

-

The differences in patient populations within and between indications.

-

The potential risk to patient safety when assessing the justification for extrapolation.

Demonstrating the biosimilarity that allows to conclude that the quality, efficacy, and safety (including immunogenicity) of the biosimilar is of such magnitude that its clinical behavior for the indications approved will be equal to the reference biological.

-

14.

How to evaluate the immunogenicity of biosimilar products? The evaluation of the immunogenicity of a biosimilar must be made (according to the complexity of the molecule) following the same principles as in the biological reference drug: Demonstration during clinical trials of the production of Anti-Drug Antibodies; triggering of anaphylactic reactions, infusion reactions, and other adverse reactions. It is evaluated using a stepped approach. First, a detection assay is used to detect the presence of Anti-Drug Antibodies (ADA) in treated patients. This is followed by confirmatory trials to determine the specificity of Anti-Drug Antibodies for the biological drug and to eliminate false positives. For positive anti-drug antibody samples, characterization assays are performed to determine the titer and type of Anti-Drug Antibodies, and bioassays or ligand binding assays are used to identify neutralizing antibodies. To assess the potential clinical impact of Anti-Drug Antibodies, immunogenicity assessments are performed in conjunction with pharmacokinetic, safety, and efficacy assessments with all the data considered.

-

15.

What is non-clinical evaluation of biosimilars to determine their efficacy and/or safety? For biosimilar drugs, non-clinical (sometimes also called “pre-clinical”) studies should be performed prior to the initiation of any clinical study with human subjects. Non-clinical data for a biosimilar product are usually generated through an abbreviated program of tests or in vitro studies, in accordance with EU guidelines.

Non-clinical studies usually include repeat dose toxicity studies, as well as pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics (FC/ FD) studies in a suitable animal model, together with local tolerance tests. The FC/FD parameters for these studies, as well as the predefined level of similarity of these parameters, should be scientifically justified to support comparability with the reference product. The purpose of these studies is to give additional support to the comparability or to detect potential differences between biosimilar and reference products.

-

16.

Do biosimilars improve accessibility to high-impact therapies? Health systems managers see biosimilars as a more economical alternative than reference biological drugs and a cost saving opportunity that contributes to the sustainability of the system. It is estimated that a biosimilar will be between 15 and 30% cheaper than the reference biological drug.

-

17.

What criteria should be taken into account to determine the value payable by health systems for a biosimilar? When it has been shown that the products are comparable and the reference product is already the standard of care, the cost minimization analysis is relevant if the Health Technology Assessment body wishes to conduct an evaluation.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kowalski, S.C., Benavides, J.A., Roa, P.A.B. et al. PANLAR consensus statement on biosimilars. Clin Rheumatol 38, 1485–1496 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04496-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04496-3