Abstract

To assess the methods and outcomes of virtual reality (VR), interventions aimed at inducing empathy and to evaluate if VR could be used in this manner for disability support worker (DSW) training, as well as highlight areas for future research. The authors conducted a scoping review of studies that used VR interventions to induce empathy in participants. We searched three databases for articles published between 1960 and 2021 using “virtual reality” and “empathy” as key terms. The search yielded 707 articles, and 44 were reviewed. VR interventions largely resulted in enhanced empathy skills for participants. Most studies agreed that VR’s ability to facilitate perspective-taking was key to inducing empathy for participants. Samples were often limited to the context of healthcare, medicine, and education. This literature provides preliminary evidence for the technology’s efficacy for inducing empathy. Identified research gaps relate to limited studies done, study quality and design, best practice intervention characteristics, populations and outcomes of interest, including lack of transfer and data across real-world settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

More than one billion people worldwide experience some form of disability that impacts their daily lives (Lollar and Chamie 2020). Each person will uniquely experience the effects of disability, owing to the underlying cause of the disability, the environment in which the person lives, and resources made available to them (World Health Organization and World Bank 2011)

Historically, disability support work has been based on a paternalistic system where people with disability were considered a passive subject, receiving care designed in a general way for disabled people, deprived of considering the person's individual needs, preferences, and characteristics (Wardana and Dewi 2017). As the disability support service sector has evolved in Australia, with the view that a more inclusive client decision-making approach offers better outcomes, along with other factors, such as population growth, life expectancy increase, technology, and changing social expectations, policies and training practices have struggled to keep up (Commonwealth of Australia 2020; Koritsas 2022; Wark et al. 2014).

Although studies on disability have stated the need for advancements in support training that facilitates personalised disability support, governments and organisations around the world continue to report that there is a lack of knowledge and understanding of people with disability in the support sector (Commonwealth of Australia 2020; Van Mierlo et al. 2012; World Health Organization and World Bank 2011). Perhaps, one way to close the “knowledge and understanding” gap is to turn to VR as a training intervention that could be designed to induce empathy in the user (trainee).

Several studies have reported empathy as a key characteristic of providing quality support to people with disability (Jorgensen et al. 2009; Koritsas 2022; Lee and Brennan 1999). A key factor as to why empathy is considered an important characteristic for support workers is because it facilitates the ability to imagine oneself in the shoes of another, which helps the support worker to construct and deliver a more meaningful and beneficial support environment (Lee and Brennan 1999). However, it has been reported that the ability and likelihood to empathise with others greatly depends on a person’s personality type (Dymond 1950). For that reason, VR’s unique ability to allow a user to experience immersive perspective-taking, irrespective of their personality type, may prove to be an effective training intervention that can bridge the gap between support workers who are sensitive to cues as to how others are feeling, and those who are not. Technology also provides an opportunity to customise the VR experience to the individual learner, giving us even greater scope for training across different personality types.

Whilst VR has been defined as the “ultimate empathy machine” (Milk 2015), some researchers have argued that there is limited empirical evidence to support this claim, as well as a lack of quality research that considers pre-existing biases and attitudes that may affect the results of different types of VR empathy interventions (Herrera et al. 2018). Moreover, the evidence that does exist, supporting VR as an effective empathy enhancing intervention, is largely the result of participants self-reporting their VR experiences to researchers (Gugliucci 2019; Swartzlander et al. 2017). This can be problematic if a variety of interfering factors, such as an individual’s ability to articulate their thoughts, or the respondent has reported what they think others would expect them to feel, rather than how they felt, have not been considered (Stueber 2019). Nevertheless, in the field of empathy assessment, whilst there are different approaches to measuring empathy, the self-reporting method continues to be the most popular approach in use today (Gilet et al. 2013; Ilgunaite et al. 2017; Lawrence et al. 2004).

Even though some studies concerning VR as an empathy inducing intervention have indicated that different kinds of VR experiences can increase empathy, a study by Martingano et al. (2021) performed a subgroup analyses that revealed that VR as an empathy inducing instrument was no more effective than traditional empathy enhancing methods like reading or imagining another person’s experience. Moreover, the researchers also discovered that the more immersive and interactive VR experiences were no more effective than those delivered by cheaper devices like cardboard headsets (Martingano et al. 2021). Similarly, Herrera et al. (2018); conducted a study to compare the short and long-term effects of a VR perspective-taking task against a traditional perspective-taking task, focused on inducing empathetic responses towards the homeless. The researchers found that the self-report empathy measures for any of the perspective-taking tasks in their study did not differ between conditions (Herrera et al. 2018). Nevertheless, the researchers did report a noticeably higher number of participants in the VR condition who signed a petition supporting affordable housing for the homeless, compared to participants in the less immersive and traditional conditions (Herrera et al. 2018).

One of the few studies involving informal caregivers as participants used a VR intervention called ‘Through the D'mentia Lens’ (TDL) that allowed users to experience what living with dementia might be like (Wijma et al. 2018). Thirty-five caregivers completed the pre-test and post-test and reported that TDL provided them with greater insight into how a person with dementia may experience situations (Wijma et al. 2018). TDL consisted of a virtual reality simulation movie and e-course that was graded 8.03 out of 10 and 7.66, respectively, for ‘acceptability’ by participants, with a significant reported improvement in empathy, confidence in supporting, and positive interactions with the person who had dementia (Wijma et al. 2018). Likewise, a study by Jütten et al. (2017) also used informal caregivers as participants to assess whether a mixed VR dementia simulator training called ‘Into D’mentia’ increased their empathy and understanding of dementia. The researchers used an intervention group (n = 145) and a control group (n = 56) and found that whilst the intervention group improved understanding of dementia over time, there were no significant differences between the two groups concerning empathy, sense of competence, and relationship quality (Jütten et al. 2017).

A study by Hargrove et al. (2020) considered the theory of ‘psychological proximity’, a theory that suggests that individuals will typically empathise easier with others who more closely resemble themselves, explored how effective VR is compared to traditional physical embodiment at increasing the ostensible closeness. In the VR group, the participants follow a 13-year-old Ethiopian girl for nine minutes as she gathers water and discusses the burden that collecting water has on her life. In the embodied activity group, participants physically carried two one-gallon water jugs through a building that was temperature-controlled to add warmth for 10 min. The findings of this study suggest that the VR experience was no more effective at inducing empathy and donations than the physical embodied experience (Hargrove et al. 2020). Moreover, it was identified by the researchers that the physical embodied group donated more than their VR peers, however not significantly higher (Hargrove et al. 2020). In addition, Sulpizio et al. (2015), found that females scored higher than the males relating to empathic concern, whereas Martingano et al. (2021) reported that gender played no significant moderating factor.

Indeed, findings on VR as an effective intervention to improve empathy range from it having no effect to having significant influence and also differing depending on the type of study done and the method used (Herrera et al. 2018; McEvoy et al. 2016; Steinfeld 2020). In addition, it has been reported that there is limited empirical evidence to support VR as an effective empathy inducing intervention (Herrera et al. 2018), and this appears to be even more so in the field of disability support work training.

The current review extends knowledge in the field of disability support work training, and the use of VR technology as an empathy enhancement tool, regardless of the context or discipline by evaluating a broader range of studies using a scoping review (Arksey and O'Malley 2005). Moreover, rather than being limited to studies focused on either ‘situational empathy’ (empathic reactions in a specific situation), or ‘dispositional empathy’ (empathy that is understood as a person’s persistent character trait) (Stueber 2019); we reviewed all studies that aimed to use virtual reality (digital) intervention to improve empathy. This includes using scenarios designed to simulate real-world situations that allow the participant to see what it is like in someone else’s shoes in an immersive and interactive manner.

2 Objectives

This scoping review aimed to assess the methods and outcomes of virtual reality (VR) interventions aimed at inducing empathy and to evaluate if VR could be used in this manner for disability support worker (DSW) training, as well as highlight areas for future research. This included assessing the types of studies done, the location and context, the extent, and what facilitators and/or barriers have been attached to the success and/or failures of the use of this technology in this context. In addition, the review aims to identify and report literature on this subject matter relating to the disability support services sector. The four research questions (RQs) for this scoping review are described below.

- (RQ1):

-

What studies have been done involving the use of VR technology as an empathy enhancement medium, and to what extent, and in what context (e.g. nursing, medicine, gaming, aged care, disability support workers) are they?

- (RQ2):

-

What are the working definitions, and are there different terminologies being used for the same practices surrounding the use of VR technology as an empathy enhancement medium (e.g. virtual reality, augmented reality)?

- (RQ3):

-

What facilitators and/or barriers have been attached to the success and/or failures of the use of VR technology in this context?

- (RQ4):

-

What is known from the existing literature about the effectiveness of VR technology as an empathy enhancement tool in the disability support worker sector?

3 Methods

3.1 Study design

Since we were interested in identifying and mapping existing knowledge and concepts pertinent to VR technology as an empathy inducing intervention, a scoping review was chosen. This methodology is especially beneficial in response to the RQs in this study.

3.2 Protocol

This study was guided based on Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) scoping review methodology, and the revised adopted framework by The Joanna Briggs Institute Scoping review manual (Peters et al. 2020). Once the research team collected relevant papers, blind screening and data assessing was performed separately by the research team using the Rayyan collaborative platform. The results were then discussed amongst the research team to fine tune any discrepancies. The research team then performed a full-text assessment for eligibility and exclusion using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 (Hong et al. 2018).

To report our findings, we used components of the PRISMA ScR Extension Fillable Checklist provided by The Joanna Briggs Institute (Peters et al. 2020). This checklist was placed at the front of the working document to facilitate a standardised review process. The review process was carried out by all three members of the research team.

3.3 Eligibility criteria

The following inclusion criteria were used for this review: (1) articles must be written in English; (2) papers must be qualitative or quantitative design; (3) the virtual reality (digital) intervention was aimed to induce empathy; (4) the scenarios must be designed to simulate real-world situations that allow the participant to see what it is like in someone else’s shoes; (5) the experience is immersive and interactive; and (6) the approach is scientific (based on research, or evaluation). A publication date limit of 1960–2021 was applied in the search phase. Articles were excluded if they were non-English written articles, used technology that lacks the ability to interactively engage, used non-computer-generated technology (e.g. role playing, use of mannequin), as well as studies that describe technology development only.

3.4 Information sources and search strategy

The method of source selection for all stages was an iterative process that involved fortnightly zoom meetings between the research team to refine direction and developments and solve any incongruities.

The research team first settled on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, followed by consultation with a librarian with expertise in health and design to ascertain best practice relating to the navigation of the university’s online library to locate useful resources for our subject area.

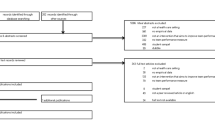

Databases searched include Web of science, Scopus, and Computers and applied sciences complete (EBSCOhost). Boolean operators were also discussed with the librarian as well as the inclusion of grey articles to attain the most relevant and comprehensive search results (Fig. 1). For this reason, literature reference lists, general google searches, as well as relevant organisations, conferences, and networks were considered as sources. Using Boolean, we searched the title, abstract, and keywords in articles. All duplications were then removed using the Rayyan web tool. Any articles lacking abstracts were appropriately located and assessed to determine their inclusion. Both title/abstract screening, and full-text screening, was initially performed by the research team. The result was then divided between the research team for blind assessment. The research team then met to resolve any conflicts. The most recent search executed prior to the screening process was in January 2021.

3.5 Study selection process

With respect to the eligibility criteria, articles were excluded if they were non-English written articles, used technology that lacks the ability to interactively engage, used non-computer-generated technology (e.g. role playing, use of mannequin), as well as studies that describe technology development only.

Owing to the nature of emerging technology, it was necessary to screen across a broad and multidisciplinary scope. To elaborate, we wanted to screen for works relating to VR technology as an empathy inducing intervention regardless of the location, context or discipline. As such, using the Rayyan web tool, we were able to highlight and screened for a combination of words and phrases where there was reference to VR technology, empathy, and user(s)/participant(s), as well as the technology’s enablement (e.g. perspective-taking, interactivity, immersive) within the titles and abstracts of articles (Fig. 2).

3.6 Methodological quality appraisal

In accordance with the MMAT critical appraisal tool, no overall score was used to assess the quality of the articles in this review (Hong et al. 2018).

3.7 Synthesis

A google form was used to collect the data from the MMAT analysis screening phase. The linked.csv file that captured the data was downloaded to a local drive and rendered as a single Microsoft Excel file. Multiple tabs were also constructed to normalise, breakdown, categorise, and map the data into workable and relevant tables for analysis, charting, validation, and coding (see appendices). The web-tool Rayyan was also frequently used as a point of reference and verification.

4 Results

The literature search returned 707 results (Fig. 3). Duplications were then removed using the Rayyan web tool, which resulted in 500 papers remaining. After both title/abstract screening, and full-text screening, 67 papers (n = 67) were divided between all three members of the research team for blind assessment. It was identified that 23 of the 67 papers failed to meet the eligibility criteria. The final result for inclusion was 44 papers (n = 44) (see Appendix 2). The following flow diagram from the PRISMA-ScR guidelines illustrates each stage of the review process (Fig. 3).

The 44 articles addressed a wide range of factors related to VR as a tool to induce empathy in participants within a variety of different contexts (see Appendix 2). Factors included discussions about the type of equipment used, the population, individuals’ experiences in different situations, and challenges and barriers that are experienced in these settings, as well as the findings and limitations of the studies.

4.1 General study characteristics

Out of the 44 articles included, 15 were done in the USA, five in the Netherlands, three in the UK, three in Cyprus, and three in Spain. Two studies were done in Australia, and two in South Korea. The remaining countries, Canada, France, Germany, Israel, Malaysia, Malta, Mexico, Italy, the Philippines, Switzerland, and Taiwan all had one study each (Table 1), (see Fig. 4). All papers included in this review were published between 2007 and 2021, with the majority (65.9%) being published after 2017 (see Appendix 2). All studies used VR technology to allow the participants, to some degree, take a first-person perspective (1PP) of what it might be like in the shoes of someone else (see Appendix 2). Finally, all studies considered how, or if, VR can be used to promote empathetic behaviours.

4.2 Studies done surrounding the use of VR technology as an empathy enhancement medium

In response to RQ1: out of the 44 articles included, 34.10% (15/44) were in the context of healthcare and medicine, making it the leading sector researching virtual reality technology as an empathy enhancement medium. In second place was the education sector with 34.10% (15/44), followed by 22.73% (10/44) of studies that fell into a broader prosocial context (see Appendix 3). Significant to the current review, no studies used ‘disability support workers’ (DSWs), and only three studies used informal caregivers (see Appendix 6).

4.3 Terminology and working definitions

In response to RQ2: out of the 44 articles included, “Virtual Reality” was the most commonly used term appearing in 97.8% (43/44) papers. Within these, 3 common working definitions were identified. This was followed by the term “Virtual environment” which appeared in 70.45% (31/44) of papers. “Empathy” was the most frequent cognitive related terminology used, appearing in 100% (44/44) studies. It was also the most frequently challenged term as it came with various definitions (see Appendix 8). The second most common cognitive related word was “Presence”, and appeared in 84.09% (37/44) studies. The most frequent word surrounding VR-related materials and hardware was “Head-mount display” appearing in 50% (22/44) studies. However, there were often alternative terms used in its place such as VR headset, which appeared in 22.73% (10/44) studies (see Appendix 8).

4.4 Facilitators attached to outcomes

In response to RQ3: out of the 44 articles included, 100% (44/44) of studies recognised perspective-taking as an important characteristic of empathy. 65.91% (29/44) papers, to some degree, ascribed VR’s capacity to enable perspective-taking as a facilitator. 45.46% (20/44) papers, noted presence, or the level of presence, as a key facilitator. It should also be noted that presence, along with immersion was frequently discussed as an interrelated factor of perspective-taking (see Appendix 10).

4.5 Barriers attached to outcomes

In response to RQ3: out of the 44 articles included, the most common reported barriers were related to a lack of “measures”, that is 56.81% (25/44). This was followed by both “sample size” and factors relating to “control and reliability”, a total of 43.19% (19/44) (see Appendix 11).

4.6 What is known from the existing literature?

In response to RQ4: out of the 44 articles included, 81.82% (36/44) of studies reported on existing literature that reinforced VR’s potential to facilitate the activation of prosocial characteristics. The remaining studies, 18.19% (8/44), reported on existing literature that used a more disputed, and/or indecisive, narrative towards VR’s capacity to facilitate the activation of prosocial characteristics (see Appendix 8). Problematic to the current review, no studies explicitly used disability support workers, with the closest cohort being informal caregivers (see Appendix 7).

5 Discussion

We performed a systematic and comprehensive scoping review that included 44 papers relating to the use of VR technology as an empathy enhancement tool. Our findings illustrate that since 2017 there has been substantial growth of interest in this area. Although not definitive, there was significant evidence to support VR as an effective intervention to induce empathy in participants, owing to its unique ability to facilitate perspective-taking, engagement, immersion, and presence (see Appendix 9). This calls into question the findings of Bang and Yildirim (2018), Deladisma et al. (2007), Herrera et al. (2018), Jütten et al. (2017), Kim et al. (2020), MacDorman (2019), McEvoy et al. (2016), and Steinfeld (2020), who found VR was not an effective intervention for enhancing empathy, or reported a more disputed, and/or indecisive outcome. In addition, some studies found interesting results when investigating the effects of viewing interventions through different display devices that are purported to facilitate a greater sense of immersion and presence, compared to less immersed systems. For example, Weinel et al. (2018) found no clear benefit in using a VR-cardboard version compared to a 360 YouTube video version, but acknowledge the inferior quality of VR-cardboard devices compared to the more expensive VR HMD solutions that offer higher resolutions and levels of immersion, which may impact the ability to induce empathy. On the other hand, Bang and Yildirim (2018) did compare a VR headset (Oculus Rift) to a YouTube 360° video, via a desktop computer, and found that even with the more expensive HMD, the empathy levels did not vary between display devices. Nevertheless, there was significant variation in the reporting and context of the studies reviewed, which could affect decision-making. Moreover, the research in this area is in its infancy, with some papers identifying important factors that weren’t considered in their study design, such as probable influences like “control”, “reliability”, and “psychometric and physiological measures”. As such, these kinds of probable influences should be considered for any future studies. Furthermore, our results suggest that the methodology used to enhance empathy via VR, can be improved. When we compared the length of the VR experience employed by the 44 studies, we identified a lack of consistency, which suggests a dearth of understanding relating to how the length of VR exposure affects participants (see Appendix 2). Similarly, we compared the types of VR head-mount display gear used and identified a significant variation between studies (see Appendix 4, Appendix 9). This suggests a lack of understanding relating to how the quality, type, and design of the equipment influences the experience. Additionally, our results suggest that the terminology and working definitions also lack consistency. When we investigated this area, we identified numerous studies that reported on the complex and/or wide-ranging definition of empathy. One explanation for this was attributed to its use by different disciplines (Stavroulia and Lanitis 2019). In any event, this lack of consensus on the meaning of empathy further highlights the need for greater definition and understanding of conditions and findings, particularly since our results illustrate the different sectors and context in which this field of research is occurring.

In regard to barriers attached to outcomes, our results suggest that a lack of measures was the most common, including the need for greater “psychometric and physiological” considerations. This was followed by sample size and diversity, and factors relating to control and reliability, which were reported by several studies to be the factor that influenced their abilities to make generalisations. In addition, we also identified other less common factors such as scenario content, time restrictions, technology, and study design limitations (see Appendix 11).

In regard to facilitators attached to outcomes, our results suggest that perspective-taking is the most commonly agreed factor that facilitates empathy. Despite the fact that VR has been labelled the “ultimate empathy machine” (Milk 2015); it is VR’s ability to allow perspective-taking, as well as other interrelated factors, such as presence, immersion, embodiment, and interactivity that has made it popular amongst researchers in this field (Barbot and Kaufman 2020; Ventura et al. 2021). The level of these factors was also reported as playing a key role in influencing prosocial change in participants, as well as other factors such as, the level of user VR experience, avatar relatability, and individual personality qualities. However, this varied across studies, suggesting a lack of consensus and understanding concerning individual facilitators and how they influence the VR experience. Therefore, it could be argued that the addition of a more holistic and longitudinal standpoint is needed to appreciate how these interrelated factors best work together in VR environments to activate prosocial qualities.

In regard to the existing literature, our results point to VR as a promising medium to facilitate the activation of prosocial characteristics, including empathy. Though some studies did provide indecisive or disputative findings, an explanation for this could be the infancy of their research as well as measuring and sample limitations.

It should be noted that there are some limitations in our scoping review. First, the nature of scoping reviews is that the focus is on breadth rather than depth of information, which is the case here. Secondly, though it is generally accepted that meta-analyses are not typical characteristics of scoping reviews, it was appropriate for our objectives to use this method to map and analyse key information. Finally, our findings are generalisable to the limitations discussed in the eligibility criteria section.

We believe our results will be useful and of interest to those researching in the field of VR as an empathy enhancement medium. The knowledge we have gained from conducting this scoping review will be used to advance our own research in this exciting and promising new area. It is clear from this scoping review, that there is a dearth of understanding and consensus in this research, and in particular, in the area of disability support workers. As such, we intend to conduct empirical research in this field, with a particular interest in contributing to the disability support sector.

6 Limitations

Because studies exploring the effectiveness of VR as an empathy enhancing intervention are in their early stages, the inclusion of quasi-experimental studies in this review may be problematic since they lack features of random assignment to VR treatment and control. Furthermore, the generalisability of findings is questionable given that interpretations are largely based on limited studies where not all variables were considered, such as “psychological proximity”, “pre-existing biases”, “cultural factors”, “gender effects”, and “practice effects”. Moreover, the results of some studies we reviewed were based on a modest sample size (Barbot and Kaufman 2020; Cheng et al. 2010; Hamilton-Giachritsis et al. 2018; Johnsen and Lok 2008; Muller et al. 2017; Trinidad and Linsangan 2018), which may not offer a true representation of the targeted population. Likewise, findings are questionable due to the lack of real-world application, conditions and environments in which evaluations occurred. In addition, there was a significant lack of studies done that used caregivers or disability support workers (DSWs) as participants, which was problematic for our research aims.

7 Conclusion

From the forty-four articles reviewed, thirty-five studies reported in the literature reinforced VR’s potential to facilitate the activation of prosocial characteristics to some degree. This is encouraging, suggesting that VR may be an acceptable intervention for DSW training. This is important since studies on disability have reported the need for advancements in support training that facilitates personalised disability support. Moreover, governments and organisations around the world continue to report that there is a lack of knowledge and understanding of people with disability in the support sector (Commonwealth of Australia 2020; Van Mierlo et al. 2012; World Health Organization and World Bank 2011). Nevertheless, studies in this field are limited and in their early stages, even more so involving DSWs as participants, which is problematic for our research focus for the current review. It is hoped that findings from this review will motivate new research in this area.

We offer some suggestions for future research. For instance, some industry sectors may traditionally have limited experience with technology. As such, it may be beneficial to pay greater attention to influencing variables, such as “practice effects” and sample size. Moreover, in industries where tight budgets tend to be the norm, such as the disability support work sector (NDS 2021; PWD 2022; Ryan and Stanford 2018); greater attention to cost-effectiveness and practicality may be beneficial towards understanding the feasibility of introducing a VR intervention into real-world settings.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Adefila A, Graham S, Clouder L, Bluteau P, Ball S (2016) myShoes—the future of experiential dementia training? J Ment Health Train Educ Pract 11(2):91–101. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMHTEP-10-2015-0048

Arksey H, O’Malley L (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 8(1):19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Bang E, Yildirim C (2018) Virtually empathetic? examining the effects of virtual reality storytelling on empathy. Springer, Cham

Barbot B, Kaufman JC (2020) What makes immersive virtual reality the ultimate empathy machine? Discerning the underlying mechanisms of change. Comput Hum Behav 111:106431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106431

Barreda-Ángeles M, Aleix-Guillaume S, Pereda-Baños A (2020) An “empathy machine” or a “just-for-the-fun-of-it” machine? effects of immersion in nonfiction 360-video stories on empathy and enjoyment. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 10:683–688. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0665

Batson C, Ahmad N (2009) Using empathy to improve intergroup attitudes and relations. Soc Issues Policy Rev 3(1):141–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-2409.2009.01013.x

Batson CD, Polycarpou MP, Harmon-Jones E, Imhoff HJ, Mitchener EC, Bednar LL, Klein TR, Highberger L (1997) Empathy and attitudes: Can feeling for a member of a stigmatized group improve feelings toward the group? J Pers Soc Psychol 72:105–118

Camilleri V, Montebello M, Dingli A, Briffa V (2017) Walking in small shoes: investigating the power of VR on empathising with children's difficulties. In: 2017 23rd international conference on virtual system & multimedia (VSMM), 31 Oct–4 Nov 2017

Buchman S, Henderson D (2019) Interprofessional empathy and communication competency development in healthcare professions’ curriculum through immersive virtual reality experiences. J Interprofess Educ Pract 15:127–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjep.2019.03.010

Campbell D, Lugger S, Sigler GS, Turkelson C (2021) Increasing awareness, sensitivity, and empathy for Alzheimer’s dementia patients using simulation. Nurse Educ Today 98:104764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104764

Cheng Y, Chiang H-C, Ye J, Cheng L-H (2010) Enhancing empathy instruction using a collaborative virtual learning environment for children with autistic spectrum conditions. Comput Educ 55(4):1449–1458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.06.008

Christofi M, Michael-Grigoriou D, Kyrlitsias C (2020) A virtual reality simulation of drug users’ everyday life: the effect of supported sensorimotor contingencies on empathy. Front Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01242

Cohen J (1992) A power primer. Psychol Bull 112:155–159

Commonwealth of Australia (2020) NDIS workforce interim report. Parliament House, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia Retrieved from https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/National_Disability_Insurance_Scheme/ImplementationForecast/Committee_Custom_Links/Interim_Report_2021

Deladisma AMMDMPH, Cohen MMD, Stevens AMD, Wagner PPD, Lok BPD, Bernard TBS, Oxendine CBS, Schumacher LPD, Johnsen KBS, Dickerson R, Raij AMS, Wells RBS, Duerson MPD, Harper JGMD, Lind DSMD (2007) Do medical students respond empathetically to a virtual patient? Am J Surg 193(6):756–760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.01.021

Dymond RF (1950) Personality and empathy. J Consult Psychol 14(5):343–350. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0061674

Formosa NJ, Morrison BW, Hill G, Stone D (2018) Testing the efficacy of a virtual reality-based simulation in enhancing users’ knowledge, attitudes, and empathy relating to psychosis. Aust J Psychol 70(1):57–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12167

Gilet A-L, Mella N, Studer J, Grühn D, Labouvie-Vief G (2013) Assessing dispositional empathy in adults: a French validation of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI). Can J Behav Sci 45(1):42–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030425

Gugliucci MR (2019) Virtual reality medical education project enhances empathy. Innov Aging 3(Suppl 1):S298

Hamilton-Giachritsis C, Banakou D, Garcia Quiroga M, Giachritsis C, Slater M (2018) Reducing risk and improving maternal perspective-taking and empathy using virtual embodiment. Sci Rep 8(1):2975–2910. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21036-2

Hargrove A, Sommer JM, Jones JJ (2020) Virtual reality and embodied experience induce similar levels of empathy change: experimental evidence. Comput Hum Behav Rep 2:100038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2020.100038

Herrera F, Bailenson J, Weisz E, Ogle E, Zaki J (2018) Building long-term empathy: a large-scale comparison of traditional and virtual reality perspective-taking. PLoS ONE 13(10):e0204494. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204494

Hong QN, Pluye P, Fabregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenaise P, Gagnon MP, Griffiths F, Nicolau B, O’Cathain A, Rousseau MC, Vedel I (2018) Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) Version 2018. In: Mixed methods appraisal tool public. McGill University, pp 1–11

Ilgunaite G, Giromini L, Di Girolamo M (2017) Measuring empathy: a literature review of available tools. Appl Psychol Bull 280:2–28

Ingram KM, Espelage DL, Merrin GJ, Valido A, Heinhorst J, Joyce M (2019) Evaluation of a virtual reality enhanced bullying prevention curriculum pilot trial. J Adolesc 71(1):72–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.12.006

Jeffrey D (2016) Empathy, sympathy and compassion in healthcare: Is there a problem? Is there a difference? Does it matter? R Soc Med 109(12):446–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076816680120

Johnsen K, Lok B (2008) An evaluation of immersive displays for virtual human experiences. In: Proceedings of the IEEE virtual reality conference, EEE; 2008. pp 133–136

Jorgensen D, Parsons M, Reid MG, Weidenbohm K, Parsons J, Jacobs S (2009) The providers’ profile of the disability support workforce in New Zealand. Health Soc Care Comm 17(4):396–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00839.x

Jütten LH, Mark RE, Maria Janssen BWJ, Rietsema J, Dröes R-M, Sitskoorn MM (2017) Testing the effectivity of the mixed virtual reality training Into D’mentia for informal caregivers of people with dementia: protocol for a longitudinal, quasi-experimental study. BMJ Open 7(8):e015702–e015702. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015702

Jütten LH, Mark RE, Sitskoorn MM (2018) Mixed virtual reality simulator into D’mentia enhance empathy and understanding and decrease burden in informal dementia caregivers? Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 3(68):453–466. https://doi.org/10.1159/000494660

Kalyanaraman S, Penn DL, Ivory JD, Judge A (2010) The virtual doppelganger: effects of a virtual reality simulator on perceptions of Schizophrenia. J Nervous Mental Dis 198(6):437–443. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181e07d66

Kang J (2018) Effect of interaction based on augmented context in immersive virtual reality environment. Wirel Person Commun 98(2):1931–1940. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11277-017-4954-0

Kim J, Jung YH, Shin Y (2020) Feasibility of a virtual reality-based interactive feedback program for modifying dysfunctional communication: a preliminary study. BMC Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00418-0

Koritsas S (2022) Decision-making support: the impact of training on disability support workers who work with adults with cognitive disability. Brain Impair. https://doi.org/10.1017/BrImp.2022.14

Kors MJL, Ferri G, Spek EDvd, Ketel C, Schouten BAM (2016) A breathtaking journey on the design of an empathy-arousing mixed-reality game. In: Proceedings of the 2016 annual symposium on computer–human interaction in play, association for computing machinery

Kors MJL, Spek EDvd, Bopp JA, Millenaar K, Teutem, RLv, Ferri G, Schouten BAM (2020) The curious case of the Transdiegetic Cow, or a mission to foster other-oriented empathy through virtual reality. In: Proceedings of the 2020 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems, Honolulu, HI, USA

Lawrence EJ, Shaw P, Baker D, Baron-Cohen S, David AS (2004) Measuring empathy: reliability and validity of the Empathy Quotient. Psychol Med 34(5):911–920. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291703001624

Lollar DJ, Chamie M (2020) International public health and global disability. In: Springer, New York, pp 149–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-0888-3_7

Lee HJ, Brennan PF (1999) Empathy in informal caregiving: extension of a concept from professional practice. J Korean Acad Nurs 29(5):1123–1133. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.1999.29.5.1123

MacDorman KF (2019) In the uncanny valley, transportation predicts narrative enjoyment more than empathy, but only for the tragic hero. Comput Hum Behav 94:140–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.01.011

Merriam-Webster (2021) earphone. Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/earphone

Misztal S, Carbonell G, Zander L, Schild J (2020) Simulating illness: experiencing visual migraine impairments in virtual reality

MFMER (2023) EEG (electroencephalogram). Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/eeg/about/pac-20393875

Milk C (2015) How virtual reality can create the ultimate empathy machine. TED Talks

Martingano AJ, Hererra F, Konrath S (2021) Virtual reality improves emotional but not cognitive empathy: a meta-analysis. Technology, Mind, and Behavior, 2, No Pagination Specified-No Pagination Specified. https://doi.org/10.1037/tmb0000034

McCarthy J (2007) What is artificial intelligence? 1–15. http://www-formal.stanford.edu/jmc/whatisai.pdf

McEvoy KA, Oyekoya O, Ivory AH, Ivory JD (2016) Through the eyes of a bystander: the promise and challenges of VR as a bullying prevention tool. In: 2016 IEEE virtual reality (VR), 19–23 March 2016

Mustapha S, Razali MM (2020) Rediscovery of empathy in youth through an interactive virtual reality experience. In: 16th IEEE international colloquium on signal processing and its applications (CSPA)

Muller DA, Kessel CRv, Janssen S (2017) Through pink and blue glasses: designing a dispositional empathy game using gender stereotypes and virtual reality. In: Extended abstracts publication of the annual symposium on computer–human interaction in play (CHI PLAY'17 extended abstracts), Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Navarrete J, Martínez-Sanchis M, Bellosta-Batalla M, Baños R, Cebolla A, Herrero R (2021) Compassionate embodied virtual experience increases the adherence to meditation practice. Appl Sci 11(3):1276

NDS (2021) Federal budget submission https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-05/171663_national_disability_services.pdf

North MS, Fiske ST (2012) An inconvenienced youth? Ageism and its potential intergenerational roots. Psychol Bull 5(138):982–997. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027843

Oh SY, Bailenson J, Weisz E, Zaki J (2016) Virtually old: Embodied perspective taking and the reduction of ageism under threat. Comput Hum Behav 60:398–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.007

Patané I, Lelgouarch A, Banakou D, Verdelet G, Desoche C, Koun E, Salemme R, Slater M, Farne A (2020) Exploring the effect of cooperation in reducing implicit racial bias and its relationship with dispositional empathy and political attitudes. Front Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.510787

PWD (2022) Peak disability org slams 2022 Federal Budget for ‘short-changing’ people with disability. People with disability Australia. https://pwd.org.au/peak-disability-org-slams-2022-federal-budget-for-short-changing-people-with-disability/

Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco A, Khalil H (2020) ‘Chapter 11: scoping reviews—JBI manual for evidence synthesis—JBI GLOBAL WIKI. JBI. https://synthesismanual.jbi.global/

Roswell RO, Cogburn CD, Tocco J, Martinez J, Bangeranye C, Bailenson JN, Wright M, Mieres JH, Smith L (2020) Cultivating empathy through virtual reality: advancing conversations about racism, inequity, and climate in medicine. Acad Med 95(12):1882–1886. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003615

Ryan R, Stanford J (2018) A portable training entitlement system for the disability support services sector. T. A. Institute. https://australiainstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/ASU_Training_Report_Formatted.pdf

Schutte NS, Stilinović EJ (2017) Facilitating empathy through virtual reality. Motiv Emot 41(6):708–712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-017-9641-7

Segovia KY, Bailenson JN (2012) Virtual imposters: responses to avatars that do not look like their controllers. Soc Influ 7(4):285–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/15534510.2012.670906

Slater P, Hasson F, Gillen P, Gallen A, Parlour R (2019) Virtual simulation training: Imaged experience of dementia. Int J Older People Nurs 14(3):e12243. https://doi.org/10.1111/opn.12243

Stark-Wroblewski K, Kreiner DS, Boeding CM, Lopata AN, Ryan JJ, Church TM (2008) Use of virtual reality technology to enhance undergraduate learning in abnormal psychology. Teach Psychol 35(4):343–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/00986280802374526

Stavroulia K, Baka E, Lanitis A, Magnenat-Thalmann N (2018) Designing a virtual environment for teacher training: Enhancing presence and empathy. In: ACM international conference proceeding series

Stavroulia K-E (2019) Designing immersive virtual training environments for experiential learning. In: Conference on object oriented programming systems languages and applications

Stavroulia KE, Lanitis A (2019) Enhancing reflection and empathy skills via using a virtual reality based learning framework. Int J Emerg Technol Learn 14(7):18–36. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v14i07.9946

Steinfeld N (2020) To be there when it happened: immersive journalism, empathy, and opinion on sexual harassment. J Pract 14(2):240–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2019.1704842

Stueber K (2019) Measuring empathy. In: The Metaphysics Research Lab (eds) Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy: Department of Philosophy, Stanford University

Sulpizio V, Committeri G, Lambrey S, Berthoz A, Galati G (2013) Selective role of lingual/parahippocampal gyrus and retrosplenial complex in spatial memory across viewpoint changes relative to the environmental reference frame. Behav Brain Res 242:62–75

Sulpizio V, Committeri G, Galati G (2014) Distributed cognitive maps reflecting real distances between places and views in the human brain. Front Hum Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00716

Sulpizio V, Committeri G, Metta E, Lambrey S, Berthoz A, Galati G (2015) Visuospatial transformations and personality: evidence of a relationship between visuospatial perspective taking and self-reported emotional empathy. Exp Brain Res 233(7):2091–2102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-015-4280-2

Swartzlander B, Dyer E, Gugliucci MR (2017) We are alfred: empathy learned through a medical education virtual reality project.

Tong X, Gromala D, Kiaei Ziabari SP, Shaw CD (2020) Designing a virtual reality game for promoting empathy toward patients with chronic pain: feasibility and usability study. JMIR Ser Games 8(3):e17354. https://doi.org/10.2196/17354

Trinidad KR, Linsangan NB (2018) Understanding the mentally disturbed’s reality through heart rate controlled virtual reality inducing artificial auditory hallucination and persecutory paranoia. Melville, New York

van Loon A, Bailenson J, Zaki J, Bostick J, Willer R (2018) Virtual reality perspective-taking increases cognitive empathy for specific others. PLoS ONE 13(8):e0202442. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202442

Van Mierlo LD, Meiland FJM, Van der Roest HG, Dröes R-M (2012) Personalised caregiver support: effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in subgroups of caregivers of people with dementia. Int. J. Geriat. Psychiatry 27(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2694

Ventura S, Cardenas G, Miragall M, Riva G, Baños R (2021) How does it feel to be a woman victim of sexual harassment? The effect of 360°-video-based virtual reality on empathy and related variables. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 24(4):258–266. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2020.0209

Wardana A, Dewi NPYP (2017) Moving away from paternalism: the new law on disability in Indonesia. Asia-Pac J Hum Rights Law 18(2):172–195. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718158-01802003

Wark S, Hussain R, Edwards H (2014) The training needs of staff supporting individuals ageing with intellectual disability. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 27(3):273–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12087

Washington E, Shaw C (2019) The effects of a VR intervention on career interest, empathy, communication skills, and learning with second-year medical students. In: Springer, Cham, pp 67–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27986-8_7

Weinel J, Cunningham S, Pickles J (2018) Deep subjectivity and empathy in virtual reality: a case study on the autism TMI virtual reality experience. In: Filimowicz M, Tzankova V (eds) New directions in third wave human-computer interaction. Springer, Cham, pp 183–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73356-2_11

Wijma EM, Veerbeek MA, Prins M, Pot AM, Willemse BM (2018) A virtual reality intervention to improve the understanding and empathy for people with dementia in informal caregivers: results of a pilot study. Aging Ment Health 22(9):1121–1129. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1348470

World Health Organization, World Bank (2011) World report on disability 2011. In: World Health Organization, Geneva

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. No funds, grants, or other support was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LT wrote the main manuscript text and prepared figures and tables. JP and RM provided supervision, validation, methodology. All authors performed blind screening and data analysis and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article. The authors declare they have no financial interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Breakdown of countries where studies were conducted and count

Appendix 2: studies reviewed with first author, title, country, objectives, sample size, display device, software, scales analysis, study design, findings – sorted by year of publication

First author, year of publication | Title | Country | Objectives | Sample size | Display Device | Software | ScalesAnalysis | Study Design | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Deladisma et al. (2007) | Do medical students respond empathetically to a virtual patient? | USA | This study investigated whether more complex communication skills, such as nonverbal behaviours and empathy, were similar when students interacted with a VP or standardised patient (SP) | 84 2nd year medical students at the University of Florida and the Medical College of Georgia | HMD | virtual patients (VP) (DIgital ANimated Avatar, DIANA) | Cronbach’s alpha (measured consistently), t-test (Comparison), Pearson’s correlation coefficient (correlation between nonverbal communicative behaviours and the observed measure of empathy) | Between-subjects (Randomised) | Medical students demonstrate nonverbal communication behaviours and respond empathetically to a VP, although the quantity and quality of these behaviours were less than those exhibited in a similar SP scenario. Student empathy in response to the VP was less genuine and not as sincere as compared to the SP scenario |

Johnsen and Lok (2008) | An Evaluation of Immersive Displays for Virtual Human Experiences | USA | This study compares a large-screen display to a non-stereo head-mounted display (HMD) for a virtual human (VH) experience | 27 medical students. 3rd year Med (13 male, 10 female). 1st year physician’s assistant school (2 male, 2 female) | HMD (non-stereo), and a fish-tank projection display (FTPD) | Interpersonal Simulator (IPS) | Self-Ratings, ANOVAs | Within-subjects (Comparison) | Results showed that student self-ratings of empathy were significantly higher in the HMD; however, when compared to observations of student behaviour, students using the large-screen display were able to more accurately reflect on their use of empathy.—Self-Ratings: students in the HMD group (M = 5.15, SD = 1.82) rated their use of empathy higher than students in the FTPD group (M = 3.64, SD = 1.34) |

Cheng et al. (2010) | Enhancing empathy instruction using a collaborative virtual learning environment for children with autistic spectrum conditions | Taiwan | The study investigated evidence of improved understanding of empathy using a collaborative virtual learning environment (CVLE)—3D empathy systems | 3 children with Autistic Spectrum Condition (ASC) who attended mainstream schools. Boys aged 8–10 | Desktop computer | collaborative virtual learning environment (CVLE)—3D empathy system. Avatars | Empathy Rating Scale (ERS) | Within-subjects | The CVLE 3D empathy system had significant and positive effects on participant use of empathy, both within the CVLE 3D empathy system and in terms of maintaining learning in understanding empathy |

Kalyanaraman et al. (2010) | The Virtual Doppelganger | USA | The study investigated the effectiveness of virtual simulations of mental illnesses in inducing empathy to combat stereotypical response | 112 participants (68 women, 44 men, mean age = 22.25 years) from a psychology research participant pool as well as from the university community | HMD, Desktop computer | VR simulation (immersive experience simulating the symptoms of schizophrenia) | Index of 12 items asking participants to rate how well a series of adjectives. Adapted from Batson et al. (1997) | Between-subjects (Randomised) | The virtual simulation + empathy condition induced greater empathy and more positive perceptions towards people suffering from schizophrenia than the control or written empathy-set condition. Interestingly, the simulation-only condition resulted in the greatest desire for social distance whereas not significantly differing on empathy and attitude measures from either the written empathy or simulation + empathy conditions |

Sulpizio et al. (2015) | Visuospatial transformations and personality: evidence of a relationship between visuospatial perspective taking and self-reported emotional empathy | Italy | The study investigated the relationship between visuospatial perspective taking and self-report measures of the cognitive and emotional components of empathy in young adults | 148 volunteers (85 females; mean age = 25 years, SD = 4.4). All subjects were right-handed | Monitor | Virtual environment used by [72, 73]. Avatar | Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) and Emotional Empathy Scale (BEES). ANOVA, Pearson’s correlation | Within-subjects | Significant gender effect on the empathy scores, with the females scoring higher than the males. 2) The main finding is that individuals who were able to more rapidly recall the target position from the perspective primed by another observer, obtained higher scores at the BEES, which assesses the tendency to share the emotional experiences of others and represents a genuine measure of emotional/affective empathy |

Adefila et al. (2016) | myShoes—the future of experiential dementia training? | UK | This study investigates the use of virtual reality (VR) to enhance experiential dementia training that would expose the user to an experience that gives them a sense of what living with dementia might be like | 55 self-selecting students studying health and social care degrees, including adult and mental health nurses, clinical psychologists, occupational therapists, paramedics, physiotherapists and social workers | HMD | Dementia simulation. Avatar | Self-assess empathy, confidence and competence (in relation to dementia patients) in pre- and post-tests. (two-tailed ANOVA test) | Within-subjects. Pilot (Exploratory study) | Despite a limited sample on which the simulation was tested, it appears to have enabled students to think beyond ‘treatment, to consider how the person might feel, and shift their approach accordingly |

Kors et al. (2016) | A Breathtaking Journey. On the Design of an Empathy-Arousing Mixed-Reality Game | Netherlands | This study investigates the use of an embodied and multisensory mixed-reality game aimed to induce empathy for refugees by providing a first-person perspective | 70 from the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany and England. Group 1: 32 participants (13 females, 19 males,). Group 2: 38 participants (13 females, 25 males) | HMD (Oculus Rift Development Kit 2) | A Breathtaking Journey (ABTJ) is an embodied mixed-reality game | Four coding schemes were supported by theoretical grounding for each code (Socially-Shared Narrative Schemas, Post-hoc Narrative Interpolations, Emotional Markers, and Embodied Feelings). To examine them more in detail, the researchers made a first broad pass coding emotional statements utilising ‘factor model for correlated basic emotions' | Between-subjects (Randomised) (Qualitative study w/grounded theory/open coding methodology) | Participants mostly expand through emotions rather than logic. This is somewhat owing to the setup of the design, but also an indication that immersive technology is able to convey complex emotional experiences |

McEvoy et al. (2016) | Through the eyes of a bystander: The promise and challenges of VR as a bullying prevention tool | USA | This study investigates the potential of virtual reality (VR) in bystander-focused bullying prevention campaigns. It compares the effects of virtual reality simulations to that of video intervention | 78 Participants in a one-factor, three-condition laboratory experiment. w/follow-up qualitative focus group study (N = 10) | HMD (Oculus Rift Development Kit), LCD monitor | Unity Software package. Avatars | item index measures w/ Cronbach's Alpha | Between-subjects (Randomised). Three conditions | The only significant effects observed were on feelings of empathy, with scores in the video condition higher than in the other two conditions, and on perceptions of bullying as a problem in participants’ schools, again with scores highest in the video condition |

Oh et al. (2016) | Virtually old: Embodied perspective taking and the reduction of ageism under threat | USA | This study investigates how the level of immersion, afforded by different media platforms, can facilitate perspective taking in demanding (presence of intergroup threat) or less demanding (absence of intergroup threat) in the context of ageism | 148 participants (53 men, 95 women) from a medium-sized western university. 64 (43.2%) were White, 47 (31.8%) were Asian, 16 (10.8%) were Latino, 11 (7.4%) were Black, and 10 (6.8%) reported another ethnicity. The mean age of the participants was 21.03 (SD ¼ 2.00) | HMD ((Oculus Rift Development Kit 2) | immersive virtual environment (IVE). Avatars | 7-point Likert-type scale w/Cronbach's a. 2 × 2 analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) tests were performed with gender and race as covariates | Between-subjects (Randomised) | Study2 (direct and concrete)—In contrast to the promising results in Study 1 (indirect), when the threat manipulation was more experiential and intentional, increasing immersion was not enough to overcome empathic avoidance. This impact of inferred intentionality also closely echoes (Segovia and Bailenson 2012) study. However, it is worth noting that intergenerational tension is typically caused by the notion that the elderly are inconveniencing the youth [75] rather than by hostile intergenerational contact |

Camilleri et al. (2017) | Walking in small shoes: investigating the power of VR on empathising with children's difficulties | Malta | This study investigates what effect a VR environment would have on the individuals’ perceptions and whether it could lead to a change towards a more empathic behaviour in a school setting | 63 participants (convenience sampling) recruited from teachers’ continuous professional development sessions, parental meetings and two educator conferences. 26.2% (male), 73.8% (female), 42.2% (25–34 age range), and 29.7% (35–44 age range) | HMD (Samsung Gear VR Headset) | The VR experience (1PP) was designed for the Headset. Head tracking technology (Unity 3D platform). The experience used the primarily visual and auditory sensory cues. 360 film (immersion) | 5-point Likert Scale for both pre- and post-VR surveys. w/ paired-samples t-test | Within-subjects | Participants did register a statistically significant change in attitude towards being able to associate to another person’s suffering |

Muller et al. (2017) | Through Pink and Blue Glasses | Netherlands | This study investigates the prospects of combining the concepts of Virtual Reality empathy games and sexism to enhance empathy | 19 participants from the faculty of Industrial Design at Eindhoven University of Technologys | HMD (HTC Vive) | Through Pink and Blue Glasses (TPBG). The experience is designed using Unity for the HTC Vive headset. Mixamo (software used to give characters a skeleton and standard animations) | 7-point Likert-scale. Empathy questions are built upon the interpersonal reactivity index (IRI) | Within-subjects | It was concluded that a relation exists between how relatable the experience is to the personal life of the player, and the stimulation of dispositional empathy. 2) being able to switch perspectives during the game turned out to help the players empathise with the other gender in real life. 3) Choosing a character can highly impact the player. 4) using thoughts and comments through sound design works for increasing the feeling of identification and creating a touching experience. 5) found a link between the feeling of credibility and the amount of people (models) in the room |

Schutte and Stilinović (2017) | Facilitating empathy through virtual reality | Australia | This study investigates whether Virtual Reality (VR) experience can prompt greater empathy. The context focuses on a young girl living in a refugee camp. It also explores whether greater engagement with VR connects VR experience to empathy | 24 university students from Australia (14 women and 10 men). Mean age of 19.92 (SD = 3.46) | VR Head-mount Used, 360 film | ‘Clouds over Sidra’ (a young girl living in a refugee camp). 360 film (immersion) | 5-point scale w/Chronbach’s alpha | Between-subjects (Randomised) | Both empathic perspective-taking and empathic concern were greater among participants in the virtual reality condition, with t(22) = 2.36, p = .03, partial eta squared = 0.20. and t(22) = 2.34, p = .03, partial eta squared = 0.20, respectively. The effect sizes for all of these comparisons between participants in the virtual reality condition and the control condition are large [76] |

Bang and Yildirim (2018) | Virtually empathetic?: Examining the effects of virtual reality storytelling on empathy | USA | The study investigates whether VR storytelling was a viable intervention for inducing a state of empathy | 44 students (15 women, 29 men). Average age of 22.35 (SD = 3.49) | HMD (Oculus Rift). Desktop computer via a YouTube 360° video | After Solitary (short documentary about a prison inmate’s solitary confinement experiences) | State Empathy Questionnaire (SEQ) 7-point Likert scale | Between-subjects | This finding suggests that watching the documentary in VR was not substantially different from watching it on YouTube with respect to the extent to which an individual empathises with the emotional experience of another person |

Hamilton-Giachritsis et al. (2018) | Reducing risk and improving maternal perspective-taking and empathy using virtual embodiment | Spain | This study investigates the use of immersive virtual reality to place parents in the position of a child to assess the effect on perspective-taking and empathy | 20 Spanish mothers aged 31 to 47 years (mean age 39.3, SD = 4.05, SE = 0.9). All participants were the biological mother of at least one child (total of 30 children, M = 1.51 children, range 1–3); children’s ages were 6 months to 15 years (M = 6.23 years, SD = 3.36, SE = 0.61) | HMD | IVR environment. Avatars | Empathy was measured in two ways: Mind in the Eyes test (general empathy) and AAPI subscale (parenting empathy). w/ANOVA | Within-subjects. Pilot (Randomised). Exploratory study | Participants reported a strong body ownership illusion for the child body that led to cognitive, emotional and physical reactions. Experiencing negative maternal behaviour increased levels of empathy. In addition, the Negative mother led to increased feelings of fear of violence. Physiological data indicated greater stress in the Negative than Positive condition |

Herrera et al. (2018) | Building long-term empathy: A large-scale comparison of traditional and virtual reality perspective-taking | USA | This study investigates two experiments that were conducted in order to compare the short and long-term effects of a traditional perspective-taking task and a VR perspective-taking | 117 participants (40 men and 75 women), and 2 participants who identified as other. The ages ranged between 15 and 57 (M = 22.94, SD = .95). 33 (28%) White, 7 (6%) Hispanic, 8 (6.8%) Indian, 49 (41.8%) Asian, 7 (6.8%) African American, and 13 (11.1%) multiracial | HMD (Oculus Rift DK2) w/infrared camera. Desktop computer | IVE (1PP). Avatars | All participants completed a pre-intervention questionnaire which included demographic questions, the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI), and the Beliefs about Empathy scale. w/ANOVA | Mixed design (Randomised) | Results show that participants who performed any type of perspective-taking task reported feeling more empathetic and connected to the homeless than the participants who only received information |

Ingram et al. (2019) | Evaluation of a virtual reality enhanced bullying prevention curriculum pilot trial | USA | This study is a pseudo-randomised pilot trial of a virtual reality enhanced bullying prevention programme among middle school students in the Midwest United States | 118 (7th and 8th grade students) from two Midwest United States middle schools. (72 control condition school, 46 experimental condition school). 55% girls, 43% boys, and 2% as non-binary or another gender. Ages ranged from 11 to 14 years (x¯ = 12.50, SD = 0.61). 25% African-American/Black, 3% Asian or Pacific Islander, 9% Hispanic/Latinx, 24% mixed race, 37% white, and 2% other. The schools were demographically similar (Intervention School: 785 students, 34% African/American/Black, 20% White, 54% female; Control School: 680 students, 33% African/American/Black, 29% White, 54% female) | HMD (Daydream goggles) | The virtual reality scenarios (realistic bully relevant scenarios using Daydream goggles), a commercially available virtual reality delivery system that has been used in previous virtual reality research | 5-item Empathy subscale of the Teen Conflict Scale. w/Cronbach's alpha | Between-subjects (Pseudo-randomised pilot trial) | The virtual reality condition yielded increased empathy from pre-to post-intervention compared to the control condition. Through the mediating role of empathy, changes in the desirable directions were also observed for traditional bullying, sense of school belonging, and willingness to intervene as an active bystander, but not for cyberbullying or relational aggression |

Jütten et al. (2018) | Can the Mixed Virtual Reality Simulator into D'mentia Enhance Empathy and Understanding and Decrease Burden in Informal Dementia Caregivers? | Netherlands | This study investigates whether the mixed virtual reality dementia simulator training Into D'mentia increased informal caregivers' understanding for people with dementia, their empathy, sense of competence, relationship quality with the care receiver, and/or decreased burden, depression, and anxiety | 145 (intervention group), 56 (control group). Group-matched on sex and level of education. All participants were adult informal caregivers (who spent at least 8 h per week on caregiving) of a relative, spouse, or friend with dementia who lived at home | Not Specified | Mixed virtual reality dementia simulator | Two subscales of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) (Davis, 1980, as cited in [21], were used to measure empathy: Perspective Taking and Empathic Concern. w/Cronbach's α. Five-point Likert scale | Between-subjects (Quasi-experimental longitudinal) | Eighty-five per cent of the participants in the intervention group found the intervention useful; 76% said they had changed their approach to caregiving, and 61% stressed that the intervention had increased their understanding of dementia. No significant differences were found between the two groups over time regarding empathy, sense of competence, relationship quality with the care receiver, burden, depression, and anxiety, at either group or individual level |

Kang (2018) | Effect of Interaction Based on Augmented Context in Immersive Virtual Reality Environment | South Korea | To verify the effect of the interaction based on augmented context, a test that compared a VR environment that replicates the real world with a VR environment to which augmented information is added was conducted | 30 men and women (ages 23–38, average age 29 years) participated in the evaluation conducted of the two different VR interfaces | HMD, Desktop computer Used, Avatars | A 3D digital girl was created for the test using the software ‘Maya’. Kinect SDK | Qualitative assessment used to determine the level of users’ emotional immersion (Scale 1 to 10) | Between-subjects | The results of the questionnaire survey indicate that the users who experienced the interaction based on augmented context were more satisfied with the contents and also felt more empathetic with the contents. This indicates that augmented information related to a story and situation in a VR space, which does not exist in the real world, positively affects the level of user immersion in terms of gesture interaction, efficiency of the interaction, and level of emotional satisfaction |

Formosa et al. (2018) | Testing the efficacy of a virtual reality‐based simulation in enhancing users’ knowledge, attitudes, and empathy relating to psychosis | Australia | This study examined the efficacy of a virtual reality (VR) education system that simulates the experience of the positive symptomology associated with schizophrenic spectrum and other psychotic disorders | 50 participants. 22 male (age range: 21–63 years) and 28 females (age range: 21–61 years), 3 students (graduated from an Australian undergraduate psychology degree. 47 individuals from the general public | VR Head-mount Used, Avatars | VR simulation in psychological education | A similar model of [77] quantitative assessment was used. Only, the items on the questionnaire were changed to measure knowledge of diagnostic criteria (The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition; American Psychiatric Association, 2013, as cited in [51]. w/Cronbach's α and point system | Within-subjects (Experimental group) | After VR exposure, participants demonstrated significantly more favourable attitudes and empathetic understanding at post-intervention compared to pre-intervention. Participant’s knowledge also measured significantly higher post intervention. In addition, gains in empathy shared a positive relationship with both fidelity and user buy-in, suggesting that the gain in empathy towards individuals diagnosed with a schizophrenic or other psychotic disorder was linked to both the emotional experience of the ‘stigmatised other’ (fidelity) and the perceived utility of VR simulation in psychological education (user buy-in) |

Stavroulia et al. (2018) | Designing a virtual environment for teacher training | Switzerland | This study aims to assess the influence of the graphical realism of a virtual classroom to the levels of presence and development of empathy skills for trainee teachers. It also investigates whether there are significant differences between training in a VR classroom and a real physical classroom and how this affects the trainee teacher | 33 participants took part in the experiment all from higher education (66.6% male and 33.3% female). 63.6% (25 to 29 age range). 27.3% (30 to 39 age range), two (50 to 59 age range), and one (18 to 24 age range). There are differences between the three groups relative to teaching experience. First group (54.6% had 1 to 2 years teaching experience), (36.4% no teaching experience at all). Second group (72.8% had 1 to 5 years teaching experience). The third group (45.5% had 1 to 5 years teaching experience), (36.4% had 6 to 10 years’ experience). Most participants were not accustomed to virtual reality technology (57.6% reported to have little user experience) | HMD (VIVE) | VR application (Developed with the Unity© game engine). The 3D avatars (teachers and students) were created using the online software Autodesk® Character Generator | Empathy Scale w/Cronbach’s Alpha and Kruskal–Wallis H test | Between-subjects, (Three conditions) | Concerning empathy, the results indicate cultivation of empathy skills. What is important is that the participants of all groups claim the importance of entering the students’ position to understand his/her perspective. There are no significant differences between the three groups except for one variable that relates with teachers’ ability to put himself/herself in the position of a student who is racially and/or ethnically different. The results revealed a significant difference between the participants that used the VR system and those who were trained in the physical environment as those who experienced the virtual world claimed that teachers can put himself/herself in the position of someone who is racially and/or ethnically different, while the physical group tend to disagree |

Trinidad and Linsangan (2018) | Understanding the mentally disturbed's reality through heart rate controlled virtual reality inducing artificial auditory hallucination and persecutory paranoia | Philippines | The study aims to develop a virtual reality (VR) system as a supplemental tool in training would be mental health clinicians | 5 young adults | HDM (OCULUS RIFT) | VR with Auditory Hallucination and Persecutory Paranoia Stimuli | Empathy scale (based on Kiersma-Chen). T-statistic measurements for heart rate sensing node. w/Shapiro–Wilk test | Within-subjects | The examination of log file entries showed the game is able to detect negative effect and adjusted the simulations’ attributes accordingly.—(T-statistic, Critical T-statistic, p-value). Based on a right-tailed test for dependent samples, the t-statistic was computed to be 0.3178 which is less than the critical t-value, 2.1318. The p-value was found to be 0.3833 which is greater than α = 0.05. Hence, there is sufficient evidence to support the claim that the virtual reality system cannot develop or enhance an individual's empathy towards a person with mental health problems. The results of the quantitative measurement suggested that the system did not enhance a player's empathy towards persons |

van Loon et al. (2018) | Virtual reality perspective-taking increases cognitive empathy for specific others | USA | The study aims to further the research on an "exercise" for the "muscle" that is empathy, which, in doing so, increases an individual's capacity to be prosocial | 180 participants from a medium-sized private university on the west coast (72 males, 106 females, and 2 individuals who identified as some other gender). Ages ranged from 18 to 29 (M = 20.28) and was racially diverse | HMD (HTC Vive) | Software not specified. Three IVEs were created independent of any participant’s responses. Steve or James Avatar | Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI). The IRI measures tendency towards empathic concern. w/Cronbach’s α | Between-subjects (Randomised), three conditions | The VRPT experience increased participants’ ensuing propensity to take the perspective of their partner, only if it was the matching individual whose perspective participants assumed in the VR. This effect of VRPT on perspective-taking was qualified by participants self-reporting of immersion in the virtual environment. The researchers found no effects of VRPT experience on behaviour in the economic games |

Weinel et al. (2018) | Deep Subjectivity and Empathy in Virtual Reality: A Case Study on the Autism TMI Virtual Reality Experience | UK | This study provides a case study of the Autism TMI Virtual Reality Experience, as a way to investigate design issues for these simulations. The study suggests that VR may offer limited benefits over 360-video for generating a sense of empathy | 20 participants were recruited from a University campus and consisted of undergraduate and postgraduate students, faculty staff and administrative staff (1 female and 19 male) | VR-cardboard and the 360 YouTube video (Viewed on Apple iMac with a built-in 21-inch display full screen mode) | The Autism Too Much Information (TMI) Virtual Reality Experience is a virtual reality (VR) application produced by The National Autistic Society (NAS) as part of an awareness campaign | Likert scale. w/two open-ended questions. A one-way MANOVA test. w/Wilk’s test | Between-subjects (Randomised) | No difference overall between the VR-cardboard and 360 YouTube formats. The results of the user experience study suggest that the participants found the Autism TMI VR Experience provides an effective means through which to communicate the subjective experience of an autistic person, leading to a sense of empathy: both groups in the study indicated high levels of agreement with the empathy overall impression. This is achieved through the use of a first-person POV representation |