Abstract

Background

Musculoskeletal conditions are the leading contributor to global disability and health burden. Manual therapy (MT) interventions are commonly recommended in clinical guidelines and used in the management of musculoskeletal conditions. Traditional systems of manual therapy (TMT), including physiotherapy, osteopathy, chiropractic, and soft tissue therapy have been built on principles such as clinician-centred assessment, patho-anatomical reasoning, and technique specificity. These historical principles are not supported by current evidence. However, data from clinical trials support the clinical and cost effectiveness of manual therapy as an intervention for musculoskeletal conditions, when used as part of a package of care.

Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to propose a modern evidence-guided framework for the teaching and practice of MT which avoids reference to and reliance on the outdated principles of TMT. This framework is based on three fundamental humanistic dimensions common in all aspects of healthcare: safety, comfort, and efficiency. These practical elements are contextualised by positive communication, a collaborative context, and person-centred care. The framework facilitates best-practice, reasoning, and communication and is exemplified here with two case studies.

Methods

A literature review stimulated by a new method of teaching manual therapy, reflecting contemporary evidence, being trialled at a United Kingdom education institute. A group of experienced, internationally-based academics, clinicians, and researchers from across the spectrum of manual therapy was convened. Perspectives were elicited through reviews of contemporary literature and discussions in an iterative process. Public presentations were made to multidisciplinary groups and feedback was incorporated. Consensus was achieved through repeated discussion of relevant elements.

Conclusions

Manual therapy interventions should include both passive and active, person-empowering interventions such as exercise, education, and lifestyle adaptations. These should be delivered in a contextualised healing environment with a well-developed person-practitioner therapeutic alliance. Teaching manual therapy should follow this model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions are leading contributors to the burden of global disability and healthcare [1]. Amongst other interventions, manual therapy (MT) has been recommended for the management of people with MSK conditions in multiple clinical guidelines, for example [2, 3].

MT has been described as the deliberate application of externally generated force upon body tissue, typically via the hands, with therapeutic intent [4]. It includes touch-based interventions such as thrust manipulation, joint mobilisation, soft-tissue mobilisation, and neurodynamic movements [5]. For people with MSK conditions, this therapeutic intent is usually to reduce pain and improve movement, thus facilitating a return to function and improved quality of life [6]. Patient perceptions of MT are, however, vague and sit among wider expectations of treatment including education, self-efficacy and the role of exercise, and prognosis [7].

Although the teaching and practice of MT has invariably changed over time, its foundations arguably remain unaltered and set in biomedical and outdated principles. This paper sets out to review contemporary literature and propose a revised model to inform the teaching and practice of MT.

The aim of this paper is to stimulate debate about the future teaching and practice of manual therapy through the proposal of an evidence-informed re-conceptualised model of manual therapy. The new model dismisses traditional elements of manual therapy which are not supported by research evidence. In place, the model offers a structure based on common humanistic principles of healthcare.

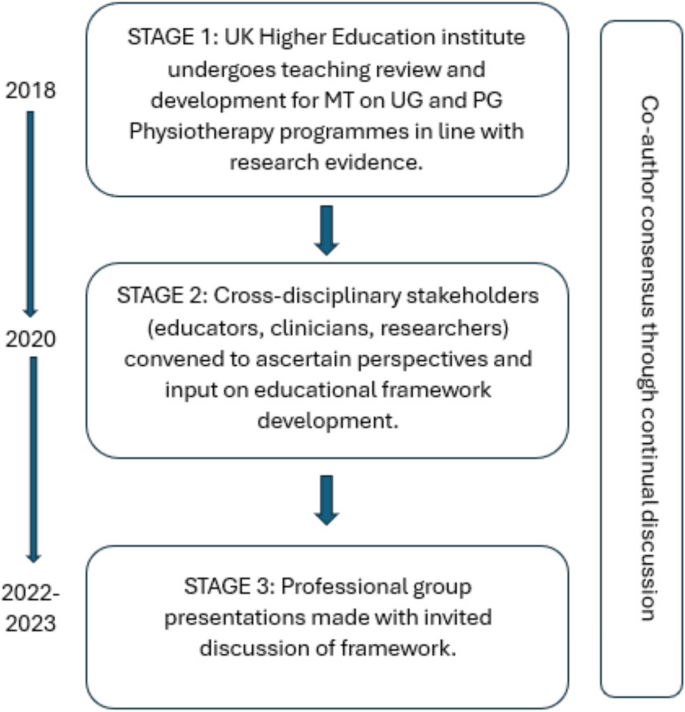

Consenus methodology

We present the literature synthesis and proposed framework as a consensus document to motivate further professional discussion developed through a simple three-stage iterative process over a 5-year period. The consensus methodology was classed as educational development which did not require ethical approval. Stage 1: a change of teaching practice was adopted by some co-authors (VG, RK, EL) on undergraduate and postgraduate Physiotherapy programmes at a UK University in 2018. This was a result of standard institutional teaching practice development which includes consideration of evidence-informed teaching. Stage 2: Input from a broader spectrum of stakeholders was sought, so a group of experienced, internationally-based educators, clinicians, and researchers from across the spectrum of manual therapy was convened. Perspectives were elicited through discussions in an iterative process. Stage 3: Presentations were made by some of the co-authors (VG, RK, SV, KY) to multidisciplinary groups (UK, Europe, North America) and feedback via questions and discussions was incorporated into further co-author discussions on the development of the framework. Consensus was achieved through repeated discussion of relevant elements. Figure 1 summarises the consensus methodology.

Clinical & cost effectiveness of manual therapy

Manual therapy has been suggested to be a valuable part of a multimodal approach to managing MSK pain and disability, for example [8]. The majority of recent systematic reviews of clinical trials report a beneficial effect of MT for a range of MSK conditions, with at least similar effect sizes to other recommended approaches, for example [9]. Some systematic reviews report inconclusive findings, for example [10], and a minority report effects that were no better than comparison or sham treatments, for example [11].

Potential benefits must always be weighed against potential harms, of course. Mild to moderate adverse events from MT (e.g. mild muscle soreness) are common and generally considered acceptable [12], whilst serious adverse events are very rare and their risk may be mitigated by good practice [13]. MT has been reported by people with MSK disorders as a preferential and effective treatment with accepted levels of post-treatment soreness [14].

MT is considered cost-effective [15] and the addition of MT to exercise packages has been shown to increase clinical and cost-effectiveness compared to exercise alone in several MSK conditions [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Further, manual therapy has been shown to be less costly and more beneficial than evidence-based advice to stay active [24].

In summary, MT is considered a useful evidence-based addition to care packages for people experiencing pain and disability associated with MSK conditions. As such, MT continues to be included in national and international clinical guidelines for a range of MSK conditions as part of multimodal care.

Principles of traditional manual therapy (TMT)

Manual therapy has been used within healthcare for centuries [4] with many branches of MT having appeared (and disappeared) over time [25]. In developed nations today, MT is most commonly utilised by the formalised professional groups of physiotherapy, osteopathy, chiropractic, as well as groups such as soft tissue therapists. All of these groups have a history that borrows heavily from traditional healers and bone-setters [26].

Although there are many elements of MT, three principles appear to have become ubiquitous within what we shall now refer to as ‘traditional manual therapy’ (TMT): clinician-centred assessment, patho-anatomical reasoning, and technique specificity [27,28,29,30]. These principles continue to influence the teaching and practice of manual therapy over recent years, for example [31].

However, they have become increasingly difficult to defend given a growing volume of empirical evidence to the contrary.

Traditional manual therapy (TMT) principles: origins and problems

Clinician-centred assessment

TMT has long had an emphasis on what we shall refer to as clinician-centred assessments. Within this, we claim, is an assumption that clinical information is both highly accurate and diagnostically important, for example [32]. Clinician-centred assessments include, for example, routine imaging, the search for patho-anatomical 'lesions’ and asymmetries, and specialised palpation. Although the focus of this paper is on the ‘hands-on’ examples of client-centred assessment, the notion of imaging is presented below to expose some of the flaws in the underlying belief system for TMT.

The emphasis on clinician-centred assessments has probably been driven, in part, by a desire for objective diagnostic tests which align well with gold-standard imaging. Indeed, since the discovery of x-rays, radiological imaging been used as an assessment for spinal pain – and a justification for using spinal manipulation – particularly in the chiropractic profession [33]. Contrary to many TMT claims, X-ray imaging is not without risk [34]. Additionally, until relatively recently (with the advent of magnetic resonance imaging) it was not widely appreciated that patho-anatomical ‘lesions’ believed to explain MSK pain conditions were nearly as common in pain-free individuals as those with pain [35]. Accordingly, the rates of unnecessary treatments, including surgery, are known to increase when imaging is used routinely [36]. For patients with non-specific low back pain, for example, imaging does not improve outcomes and risks overdiagnosis and overtreatment [37]. Hence, despite being objective in nature, the value of imaging for many MSK pain conditions (particularly spinal pain) has reduced drastically with clinical guidelines across the globe recommending against routine imaging for MSK pain of non-traumatic origin [38]. Even so, the practice of routine imaging continues [39].

Hands-on interventions are inextricably related to hands-on assessment [40], and often associated with claims of ‘specialisation’ [41]. By this we mean where a great level of training and precision are claimed to be necessary for influencing the interpretation of assessment findings, treatment decisions, and/or treatment outcomes. Implicit within this claim is that therapists who are unable to achieve such precision are not able to perform MT to an acceptable level (and thereby are not able to provide benefit to patients).

There are numerous studies that cast doubt over claims of highly specialised palpation skills. Palpation of anatomical landmarks does not reach a clinically acceptable level of validity [42]. Specialised motion palpation does not appear to be a good method for differentiating people with or without low back pain [43]. Poor content validity of specialised motion tests have been reported, in line with a lack of acceptable reference standards [44]. Palpable sensations reported by therapists are unlikely to be due to tissue deformation [45]. Furthermore, the delivery of interventions based on specialised palpatory findings is no better than non-specialised palpation [46]. Generally poor reliability of motion palpation skills has been reported, for example [47] and appear to be independent of clinician experience or training, for example [48]. Notably, person-centred palpation—for pain and tenderness for example—has slightly higher reliability, but is still fair at best [49].

This does not mean that palpation is of no use at all though; just that effective manual therapy does not depend upon it. For example, expert therapists can display high levels of interrater reliability during specialised motion palpation [50]. Focused training can improve the interrater reliability of specialised skills [51]. However, the validity of the phenomenon remains poor. Given the weight of the evidence and consistency of data over recent decades, we suggest that the role of clinician-centred hands-on assessment is no longer central to contemporary manual therapy.

Patho-anatomical reasoning

The justification for selecting particular MT interventions has historically been based upon the patho-anatomical status of local peripheral tissue [52,53,54,55]. Patho-anatomical reasoning, we propose, is the framework that links clinician-centred assessments to the desire for highly specific delivery of MT interventionsKey to this is the relationship between a patho-anatomic diagnosis and the assumed mechanisms of action of the intervention employed.

Theories for the mechanisms of action of MT interventions are many. Some of the most prominent include reductions of disc herniations [56], re-positioning of a bone or joint [32], removal of intra-articular adhesions [57], changes in the biomechanical properties of soft tissues [58], central pain modulation [59], and biochemical changes [60]. These theories have been used to justify the choice of certain interventions: a matching of diagnosis (i.e., existence of a lesion) to the effect of treatment takes place. However, most of these mechanistic theories either lack evidence or have been directly contested [61].

The causal relationship between proposed tissue-based factors such as posture, ergonomic settings, etc. and painful experience has also been disputed [62]. Although local tissue stiffness has been observed in people with pain, this is typically associated with neuromuscular responses, rather than patho-anatomical changes at local tissue level [63,64,65,66]. Overall, although some local tissue adaptions have been identified in people with recurrent MSK pain, this is inconsistent and the evidence is currently of low quality [67] are generally limited to short-term follow-up measures [68].

Technique specificity

TMT techniques have been taught with an emphasis that a particular direction, ‘grade’ of joint movement, or deformation of tissue at a very specific location in a certain way, is required to achieve a successful treatment outcome.

One problem with a demand for technique specificity in manual therapy is that an intervention does not always result in the intended effect. For example, posteroanterior forces applied during spinal mobilization consistently induce sagittal rotation, as opposed to the assumed posteroanterior translation, for example [69]. Furthermore, irrespective of the MT intervention chosen, restricting movements to a particular spinal segment is difficult and a regional, non-specific motion is typically induced, for example [70].

To support technique specificity, comparative data must repeatedly and reproducibly show superiority of outcome from specific MT interventions over non-specific MT, which is consistently not observed [71,72,73]. Some studies have demonstrated localised effects of targeted interventions [74] but there appears to be no difference in outcome related to: the way in which techniques are delivered [75]; whether technique selection is random or clinician-selected [41]; or variations in the direction of force or targeted spinal level [76]. Conversely, there is evidence that non-specific technique application may improve outcomes [77,78,79]. Further, sham techniques produce comparable results to specialised approaches [11].

Passive movement and localised touch have been associated with significant analgesic responses [80]. These data indicate the presence of an analgesic mechanism. Unfortunately, mechanistic explanation for the therapeutic effects of MT upon pain and disability still remain largely in a ‘black box’ state [81]. Nevertheless, there are several plausible mechanisms of action to explain the analgesic action of MT interventions, including the activation of modulatory spinal and supraspinal responses [82,83,84,85]. In support of this, MT interventions have been associated with a variety of neurophysiological responses [61]. However, it must be acknowledged that these studies provide mechanistic evidence based on association, which is insufficient to make causal claims [86]. Importantly, none of these neurophysiological responses have been directly related to either the analgesic mechanisms or clinical outcome and may therefore be incidental.

There is evidence that MT does not provide analgesia in injured tissues [87, 88]. Conversely, MT has been shown to decrease inflammatory biomarkers [89,90,91,92,93], although these changes have not been evaluated in the longer-term, nor associated with clinical outcomes.

A modern framework for manual therapy

We propose a new direction for the future of MT in which the teaching and practice of this core dimension of MSK care are no longer based on the traditional principles of clinician-centred assessment, patho-anatomical reasoning, and technique specificity.

In doing so, this framework places MT more explicitly as part of person-centred care and appeals to common principles of healthcare, best available evidence, and contemporary theory which avoids unnecessary and over-complicated explanations of observed effects. The framework is simple in terms of implementation and delivery and contextualised by common elements of best practice for healthcare, in line with regulated standard of practice, e.g., [94,95,96,97]. Our proposal simply illustrates the operationalisation of these common elements through manual therapy.

Too much emphasis has been given to clinician-centred assessments and this should be rebalanced with an increased use of patient-centred assessments, such as a thorough case history, the use of validated patient-reported outcome measures (PROMS), and real-time patient feedback during assessments.

The new framework considers fundamental and humanistic dimensions of touch-based therapies, such as non-specific neuromodulation, communication and sense-making, physical education, and contextual clinical effectiveness. This aligns to contemporary ideas regarding therapeutic alliance and a move towards genuinely holistic healthcare [98, 99]. The framework needs to be “open” in order to represent and allow expression of the complexity of the therapeutic encounter. However, to prevent the exploitation of this openness the framework is underpinned by evidence, and any manual therapy approaches without plausible and measurable mechanisms are not supported.

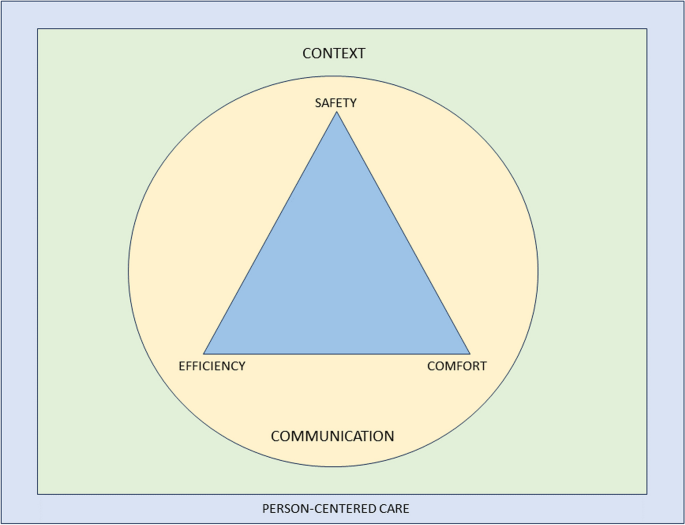

To provide the best care, common healthcare elements such as the safety and comfort of the person seeking help and therapist must be considered, and care should be provided as efficiently as possible. Our framework embraces these dimensions and employs an integration of current evidence. It is transdisciplinary in nature and may be adopted by all MT professions. Figure 1 provides a graphical representation of the framework. It is acknowledged that all components overlap, relate, and influence each. There are two main components: the practical elements on the inside, comprised of safety, comfort, and efficiency, and the conceptual themes on the outer regions, consisting of communication, context, and person-centred care Fig. 2.

Representation of a modern teaching and practice framework for manual therapy. The image is purposefully designed to be simple, and has been developed primarily to be used as a teaching aid. When displayed in a learning environment, learners and clinicians can quickly refer to the image to check their practice against each element. To keep the image clear, each element of the image is described in detail in the text below”

Practical elements

Safety

Safety for people seeking help is a primary concern for all healthcare providers, with the aims to “prevent and reduce risks, errors and harm that occur to patients [sic] during provision of health care… and to deliver quality essential health services” [100]. This, and the notion of safety more generally (including that of the therapist), should be central to way MT is taught and practised.

A fundamentally safe context should be created where there is an absence of any obvious danger or risk of harm to physical or mental health. Consideration should be given to ensuring that communication and consent processes are orientated towards the safety of both the person seeking help and the therapist. The therapist should pay attention to any sense of threat that could be present in the physical, emotional, cognitive and environmental domains of the clinical encounter, and use skilful communication to mitigate anxiety about the assessment or therapeutic process.

Safety should also be considered in the clinical context of the assessment and treatment approach, ensuring that relevant and meaningful safety screenings have been undertaken [67, 101]. There remains a need for good, skilful practice and development of manually applied techniques, but this can be achieved without reference to the principles of TMT and without the dogma of a proprietary therapeutic approach.

Comfort

Comfort suggests that both the person seeking help and the therapist are physically and emotionally content during the assessment and therapeutic process. For example, the person seeking help is agreeable with any necessary state of dress (sociocultural difference should be considered); the person is relaxed and untroubled in whatever position they are in, and is adequately supported whether sitting, standing or recumbent during assessment and treatment; the therapist is comfortable with their positioning and posture; any discomfort produced by the therapeutic process is negotiated and agreed. Any physical mobilisation or touch should be applied with respect to the feedback from the person in relation to their comfort, rather than a pre-determined force based on the notion of resistance. This process requires clinical phronesis, sensitivity, responsivity, dexterity, and embodied communication [102].

Efficiency

The therapeutic process should be undertaken in a well-organised, competent manner aiming to achieve maximum therapeutic benefit with minimum waste of effort, time, or expense. To enhance the efficiency dimension, the assessment and therapeutic process should be an integral part of a holistic educational and/or activity-based approach to the management of the people which might also address psychological, nutritional, or ergonomic aspects of care, while being aware of social determinants to health. Recommendations exist which serve as a useful guide for enhancing care and promoting self-management in an efficient way [103].

A principle of this new model of MT is that therapists should not lose sight of the goals they develop with the people they help and ensure that there is coherence between their management aims and their techniques. Therapists should aim to support a person’s self-efficacy and use active approaches to empower them in their recovery. The overall number of therapeutic applications should be made in the context of fostering therapeutic alliance and supporting people to make sense of their situation and symptoms. This should be informed by contemporary views of the effects of manual therapy, emphasising a “physical education process” to promote sense-making and self-efficacy in alliance with the people they aim to help.

Clinical interactions need to be reproducible under a person’s own volition, serving to enhance self-empowerment. For example, someone could be taught how to “self-mobilise” if a positive effect is found with a particular therapeutic application. This should be appropriately scaffolded with behavioural change principles and functional contextualism that promote autonomy and self-management, rather than inappropriate reliance on the therapist [103, 104].

An important and emergent notion from the proposed model is to question what constitutes indications for MT given that the model excludes traditional factors which would have informed whether manual therapy is indicated or not for a particular person. The response to this sits within the efficiency and safety dimensions: MT can be beneficial as part of a multi-dimensional approach to management across a broad population of people with musculoskeletal dysfunction, with no evidence to suggest any clinician-centered or patho-anatomical finding influences outcomes. The choice of whether or not to include MT as part of a management strategy should therefore be a product of a lack of contraindications and shared-decision making.

This framework aligns with evidence-based propositions that effectiveness and efficiency in assessment, diagnosis, and outcomes are not reliant on the therapist’s skill set of specialised elements of TMT, but rather other factors—for example variations in pain phenotypes [5].

Conceptual themes

Communication

Communication is the overriding critical dimension to the whole therapeutic process and should be aimed at addressing peoples’ fundamental needs to make sense of their symptoms and path to recovery. The delivery and uptake of the therapy should therefore be operationalised in a communication process that meaningfully represents shared-decision making and the best possible attempt to contextualise the therapy in positive and evidence-informed explanations of the process and desired effects [105].

Within a therapeutic encounter, practitioners must give the time to listen to peoples’ accounts and explanations of their symptoms, including their ideas about their cause [106]. The assessment and diagnostic process should be a shared endeavour, for example, the negotiation of symptom reproduction. This should be done in a manner that facilitates sense-making, and which simultaneously encourages people to move on from unhelpful beliefs about their symptoms [107, 108], encouraging understanding of the uncertain nature of pain and injury. Person-centered communication requires attention to what we communicate and how we communicate across the entire clinical interaction including interview, examination, and management planning [109]. Therapists need to be open, reflective, aware and responsive to verbal and non-verbal cues, and demonstrate a balance between engaging with people (e.g. eye-gaze) and writing/typing notes during the interview [110,111,112].

People should be given the opportunity to discuss their understanding of the diagnosis and options for treatment and rehabilitation. The decision-making process is dialogical, in which alternative options to the offered therapy should also be discussed with the comparative risks and benefits of all available management options, including doing nothing [113, 114].

The therapist must fully appreciate the potential consequences of touch without consent. Continual dialogue should ensure that all parties are moving towards mutually agreed goals. The context of the therapy should be explicitly communicated to give appropriate context for any particular intervention as part of a holistic, evidence-based approach [115,116,117]. Therapists should be aware that their own beliefs can affect the way they communicate with their people; in the same way, a person’s context affects how they communicate what they expect from their treatment [107, 118,119,120]. The construction of contextual healing scenarios which support positive outcomes, whilst minimising nocebic effects, is critical to effective healthcare [121,122,123].

There is a growing academic interest in the nature, role, and purpose of social and affective touch, and any re-framing of MT should consider touch as a means of communication to develop and enhance cooperative communications and strengthen the therapeutic relationship [124,125,126,127,128,129]. It can be soothing for a person in pain to experience the caring touch of a professional therapist [130]; on the other hand, probing, diagnostic, and touch can be experienced as alienating [131,132,133]. Touch can alter a person’s sense of body ownership and their ability to recognise and process their emotions by modulating interoceptive precision [129, 134, 135], and intentional touch may be perceived differently from casual, unfocussed touch [136, 137]. There is also a thesis that touch generates shared understanding and meaning [138,139,140]. This wider appreciation of touch should be embedded in modern MT communication.

Context

The contextual quality of a person’s experience of the therapeutic encounter can affect satisfaction and clinical outcomes [141,142,143,144,145]. The context in which therapeutic care takes place should therefore be developed to enhance this experience. There could be very local, practical aspects of the context, such as the type of passive information available in the clinical space, e.g. replacing biomedical and pathological imagery and objects with positive, active artefacts; judicious and thoughtful organisation and use of treatment tables to discourage a sense of passivity and disempowerment; allocating a comfortable space where communication can take place; colour schemes and light sources which facilitate positivity; ensuring consistency through all clinical and administrative staff promoting encouraging and non-nocebic messages. Importantly, the way the therapist dresses influences peoples’ perception of their healthcare experience [146, 147], and that in turn should be contextually and culturally sensitive [148,149,150].

Beyond the local clinical space is the broader social environment. The undertaking of MT should serve a role in a person’s engagement with their social environment. For example, someone returning home after engaging with their therapist and disseminating positive health messages within their home and social networks; people acting as advocates for self-empowered healthcare. Furthermore, early data have demonstrated that aligning treatment with the beliefs and values of culturally and linguistically diverse communities enhances peoples’ engagement with their healthcare [151].

Person-centred care

Here we borrow directly from one of the most established and clinically useful definitions of Person-Centered Medicine [152]:

“(Person-Centered Medicine is) an affordable biomedical and technological advance to be delivered to patients [sic] within a humanistic framework of care that recognises the importance of applying science in a manner that respects the patients [sic] as a whole person and takes full account of [their] values, preferences, aspirations, stories, cultural context, fears, worries and hopes and thus that recognises and responds to [their] emotional, social and spiritual necessities in addition to [their] physical needs” [152], p219.

Person-centred care incorporates a person’s perspective as part of the therapeutic process. In practice, therapists need to communicate in a manner that creates adequate conversational space to elicit a person’s agenda (i.e. understanding, impact of pain, concerns, needs, and goals), which guides clinical interactions. This approach encourages greater partnership in management [109, 153, 154].

A roadmap outlining key actions to implement person-centeredness in clinical practice has been outlined in detail elsewhere [155]. This includes screening for serious pathology, health co-morbidities and psychosocial factors; adopting effective communication; providing positive health education; coaching and supporting people towards active self-management; and facilitating and managing co-care (when needed) [154].

It is critical and necessary now to make these features explicit and central to the revised model of MT proposed in this paper. We wish to identify common ground across all MT professions in order to achieve a trans-disciplinary understanding of the evidence supporting the use of MT.

We acknowledge that our arguments here are rooted in empiricism and deliberately based on available research data from within the health science disciplines. We also acknowledge that there is a wider debate about future directions in person-centred care arising from the current evolution of the evidence-based health care movement, which has pointed to the need to learn more about peoples’ lived experiences, to redefine the model of the therapeutic relationship. Although beyond the scope of this paper, a full exploration of modern health care provision involves reconsideration of the ethics and legal requirements of communication and shared decision-making [156,157,158,159]. The authors envision this paper as a stimulus for self-reflection, stakeholder discussions, and ultimately change that can positively impact outcomes for people who seek manual therapy interventions.

Conclusions

Manual therapy has long been part of MSK healthcare and, given that is likely to continue. Current evidence suggests that effectiveness does not rely on the traditional principles historically developed in any of the major manual therapies. Therefore, the continued teaching and practice based on the principles of clinician-centred palpation, patho-anatomical reasoning, and technique specificity are no longer justified and may well even limit the value of MT.

A revised and reconceptualised framework of MT, based on the humanistic domains of safety, comfort and efficiency and underpinned by the dimensions of communication, context and person-centred care will ensure an empowering, biopsychosocial, evidence-informed approach to MSK care. We propose that the future teaching and practice of MT in physiotherapy, osteopathy, chiropractic, and all associated hands-on professions working within the healthcare field should be based on this new framework.

Availability of data and materials

N/A.

References

Young C, Argáez C. CADTH Rapid Response Reports. Manual Therapy for Chronic Non-Cancer Back and Neck Pain: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Copyright © 2020 Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health.; 2020.

Blanpied PR, Gross AR, Elliott JM, Devaney LL, Clewley D, Walton DM, et al. Neck Pain: Revision 2017. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017;47(7):A1-a83.

NICE. Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management. NICE guideline [NG59]. 2016.

Pettman E. A history of manipulative therapy. J Man Manip Ther. 2007;15(3):165–74.

Damian K, Chad C, Kenneth L, David G. Time to evolve: the applicability of pain phenotyping in manual therapy. J Man Manip Ther. 2022;30(2):61–7.

McCarthy CJ. Combined Movement Theory: Rational Mobilization and Manipulation of the Vertebral Column. London, UK: Churchill Livingstone; 2010.

Subialka JA, Smith K, Signorino JA, Young JL, Rhon DI, Rentmeester C. What do patients referred to physical therapy for a musculoskeletal condition expect? A qualitative assessment. Musculoskel Sci Pract. 2022;59:102543.

Louw A, Nijs J, Puentedura EJ. A clinical perspective on a pain neuroscience education approach to manual therapy. J Man Manip Ther. 2017;25(3):160–8.

Wilhelm M, Cleland J, Carroll A, Marinch M, Imhoff M, Severini N, et al. The combined effects of manual therapy and exercise on pain and related disability for individuals with nonspecific neck pain: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J Man Manip Ther. 2023;31(6):393–407.

Schenk R, Donaldson M, Parent-Nichols J, Wilhelm M, Wright A, Cleland JA. Effectiveness of cervicothoracic and thoracic manual physical therapy in managing upper quarter disorders - a systematic review. J Man Manipulative Therap. 2021:1–10.

Lavazza C, Galli M, Abenavoli A, Maggiani A. Sham treatment effects in manual therapy trials on back pain patients: a systematic review and pairwise meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(5):e045106.

Funabashi M, Pohlman KA, Goldsworthy R, Lee A, Tibbles A, Mior S, et al. Beliefs, perceptions and practices of chiropractors and patients about mitigation strategies for benign adverse events after spinal manipulation therapy. Chiropr Man Therap. 2020;28(1):46.

Rushton A, Carlesso LC, Flynn T, Hing WA, Rubinstein SM, Vogel S, et al. International Framework for Examination of the Cervical Region for Potential of Vascular Pathologies of the Neck Prior to Musculoskeletal Intervention: International IFOMPT Cervical Framework. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2022;53(1):7–22.

Thomas M, Thomson OP, Kolubinski DC, Stewart-Lord A. The attitudes and beliefs about manual therapy held by patients experiencing low back pain: a scoping review. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2023;65:102752.

Lilje S, van Tulder M, Wykman A, Aboagye E, Persson U. Cost-effectiveness of specialised manual therapy versus orthopaedic care for musculoskeletal disorders: long-term follow-up and health economic model. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2023;15:1759720x221147751.

Abbott JH, Robertson MC, Chapple C, Pinto D, Wright AA, Leon de la Barra S, et al. Manual therapy, exercise therapy, or both, in addition to usual care, for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: a randomized controlled trial. 1: clinical effectiveness. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21(4):525–34.

Bove AM, Smith KJ, Bise CG, Fritz JM, Childs JD, Brennan GP, et al. Exercise, Manual Therapy, and Booster Sessions in Knee Osteoarthritis: Cost-Effectiveness Analysis From a Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Phys Ther. 2018;98(1):16–27.

Leininger B, McDonough C, Evans R, Tosteson T, Tosteson AN, Bronfort G. Cost-effectiveness of spinal manipulative therapy, supervised exercise, and home exercise for older adults with chronic neck pain. Spine J. 2016;16(11):1292–304.

Tsertsvadze A, Clar C, Court R, Clarke A, Mistry H, Sutcliffe P. Cost-effectiveness of manual therapy for the management of musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review and narrative synthesis of evidence from randomized controlled trials. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2014;37(6):343–62.

UK Beam Trial Team. United Kingdom back pain exercise and manipulation (UK BEAM) randomised trial: effectiveness of physical treatments for back pain in primary care. BMJ. 2004;329(7479):1377.

UK Beam Trial Team. United Kingdom back pain exercise and manipulation (UK BEAM) randomised trial: cost effectiveness of physical treatments for back pain in primary care. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2004;329(7479):1381.

van Dongen JM, Groeneweg R, Rubinstein SM, Bosmans JE, Oostendorp RA, Ostelo RW, et al. Cost-effectiveness of manual therapy versus physiotherapy in patients with sub-acute and chronic neck pain: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Spine J. 2016;25(7):2087–96.

Woods B, Manca A, Weatherly H, Saramago P, Sideris E, Giannopoulou C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of adjunct non-pharmacological interventions for osteoarthritis of the knee. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(3):e0172749.

Aboagye E, Lilje S, Bengtsson C, Peterson A, Persson U, Skillgate E. Manual therapy versus advice to stay active for nonspecific back and/or neck pain: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Chiropr Man Therap. 2022;30(1):27.

Paris SV. A History of Manipulative Therapy Through the Ages and Up to the Current Controversy in the United States. J Man Manipulative Ther. 2000;8(2):66–77.

MacDonald CW, Osmotherly PG, Parkes R, Rivett DA. The current manipulation debate: historical context to address a broken narrative. J Man Manipulative Therap. 2019;27(1):1–4.

Fryer G. Intervertebral dysfunction: a discussion of the manipulable spinal lesion. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2003;6(2):64–73.

McCarthy CJ. Spinal manipulative thrust technique using combined movement theory. Man Ther. 2001;6(4):197–204.

Vickers A, Zollman C. ABC of complementary medicine Massage therapies. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 1999;319(7219):1254–7.

Evans DW. Osteopathic principles: More harm than good? Int J Osteopath Med. 2013;16(1):46–53.

Mourad F, Yousif MS, Maselli F, Pellicciari L, Meroni R, Dunning J, et al. Knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes of spinal manipulation: a cross-sectional survey of Italian physiotherapists. Chiropr Man Therap. 2022;30(1):38.

Cyriax JH, Cyriax PJ. Cyriax's Illustrated Manual of Orthopaedic Medicine. 3rd ed: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1996.

Young KJ. Words matter: the prevalence of chiropractic-specific terminology on Australian chiropractors’ websites. Chiropr Man Therap. 2020;28(1):18.

Jenkins HJ, Downie AS, Moore CS, French SD. Current evidence for spinal X-ray use in the chiropractic profession: a narrative review. Chiropr Man Therap. 2018;26:48.

Brinjikji W, Luetmer PH, Comstock B, Bresnahan BW, Chen LE, Deyo RA, et al. Systematic literature review of imaging features of spinal degeneration in asymptomatic populations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36(4):811–6.

Mafi JN, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Landon BE. Worsening trends in the management and treatment of back pain. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(17):1573–81.

Hall AM, Aubrey-Bassler K, Thorne B, Maher CG. Do not routinely offer imaging for uncomplicated low back pain. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2021;372:n291.

Lin I, Wiles L, Waller R, Goucke R, Nagree Y, Gibberd M, et al. What does best practice care for musculoskeletal pain look like? Eleven consistent recommendations from high-quality clinical practice guidelines: systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(2):79.

Hall AM, Scurrey SR, Pike AE, Albury C, Richmond HL, Matthews J, et al. Physician-reported barriers to using evidence-based recommendations for low back pain in clinical practice: a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):49.

Eriksson L, Ekenberg L, Melander-Wikman A. The concept of palpation of the shoulder – A basic element of physiotherapy practice: A focus group study with physiotherapists. Adv Physiother. 2012;14(4):183–93.

Nim CG, Downie A, O’Neill S, Kawchuk GN, Perle SM, Leboeuf-Yde C. The importance of selecting the correct site to apply spinal manipulation when treating spinal pain: Myth or reality? A systematic review. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):23415.

Alexander N, Rastelli A, Webb T, Rajendran D. The validity of lumbo-pelvic landmark palpation by manual practitioners: A systematic review. Int J Osteopath Med. 2021;39:10–20.

Leboeuf-Yde C, van Dijk J, Franz C, Hustad SA, Olsen D, Pihl T, et al. Motion palpation findings and self-reported low back pain in a population-based study sample. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2002;25(2):80–7.

Najm WI, Seffinger MA, Mishra SI, Dickerson VM, Adams A, Reinsch S, et al. Content validity of manual spinal palpatory exams - A systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2003;3:1.

Chaudhry H, Schleip R, Ji Z, Bukiet B, Maney M, Findley T. Three-dimensional mathematical model for deformation of human fasciae in manual therapy. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2008;108(8):379–90.

Gabriel A, Konrad A, Roidl A, Queisser J, Schleip R, Horstmann T, et al. Myofascial Treatment Techniques on the Plantar Surface Influence Functional Performance in the Dorsal Kinetic Chain. J Sports Sci Med. 2022;21(1):13–22.

Nolet PS, Yu H, Côté P, Meyer A-L, Kristman VL, Sutton D, et al. Reliability and validity of manual palpation for the assessment of patients with low back pain: a systematic and critical review. Chiropr Man Therap. 2021;29(1):33.

Seffinger MA, Najm WI, Mishra SI, Adams A, Dickerson VM, Murphy LS, et al. Reliability of spinal palpation for diagnosis of back and neck pain: a systematic review of the literature. Spine. 2004;29(19):E413–25.

Beynon AM, Hebert JJ, Walker BF. The interrater reliability of static palpation of the thoracic spine for eliciting tenderness and stiffness to test for a manipulable lesion. Chiropr Man Therap. 2018;26:49.

Petersen EJ, Thurmond SM, Shaw CA, Miller KN, Lee TW, Koborsi JA. Reliability and accuracy of an expert physical therapist as a reference standard for a manual therapy joint mobilization trial. J Man Manip Ther. 2021;29(3):189–95.

Petersen EJ, Thurmond SM, Buchanan SI, Chun DH, Richey AM, Nealon LP. The effect of real-time feedback on learning lumbar spine joint mobilization by entry-level doctor of physical therapy students: a randomized, controlled, crossover trial. J Man Manip Ther. 2020;28(4):201–11.

Abbott JH, Flynn TW, Fritz JM, Hing WA, Reid D, Whitman JM. Manual physical assessment of spinal segmental motion: intent and validity. Man Ther. 2009;14(1):36–44.

Bialosky JE, Simon CB, Bishop MD, George SZ. Basis for spinal manipulative therapy: a physical therapist perspective. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2012;22(5):643–7.

Henderson CN. The basis for spinal manipulation: chiropractic perspective of indications and theory. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2012;22(5):632–42.

Sizer PS Jr, Felstehausen V, Sawyer S, Dornier L, Matthews P, Cook C. Eight critical skill sets required for manual therapy competency: a Delphi study and factor analysis of physical therapy educators of manual therapy. J Allied Health. 2007;36(1):30–40.

Ombregt L. A System of Orthopaedic Medicine: Elsevier; 2013.

Cramer GD, Henderson CN, Little JW, Daley C, Grieve TJ. Zygapophyseal joint adhesions after induced hypomobility. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33(7):508–18.

George JW, Tunstall AC, Tepe RE, Skaggs CD. The Effects of Active Release Technique on Hamstring Flexibility: A Pilot Study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(3):224–7.

Bialosky JE, Bishop MD, Price DD, Robinson ME, George SZ. The mechanisms of manual therapy in the treatment of musculoskeletal pain: a comprehensive model. Man Ther. 2009;14(5):531–8.

Plaza-Manzano G, Molina-Ortega F, Lomas-Vega R, Martínez-Amat A, Achalandabaso A, Hita-Contreras F. Changes in biochemical markers of pain perception and stress response after spinal manipulation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014;44(4):231–9.

Zusman M. Mechanism of mobilization. Physical Therapy Reviews. 2011;16(4):233–6.

De Carvalho DE, de Luca K, Funabashi M, Breen A, Wong AYL, Johansson MS, et al. Association of Exposures to Seated Postures With Immediate Increases in Back Pain: A Systematic Review of Studies With Objectively Measured Sitting Time. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2020;43(1):1–12.

Colloca CJ, Keller TS. Stiffness and neuromuscular reflex response of the human spine to posteroanterior manipulative thrusts in patients with low back pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2001;24(8):489–500.

Colloca CJ, Keller TS, Gunzburg R. Biomechanical and neurophysiological responses to spinal manipulation in patients with lumbar radiculopathy. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2004;27(1):1–15.

Reed WR, Long CR, Kawchuk GN, Sozio RS, Pickar JG. Neural Responses to Physical Characteristics of a High-velocity, Low-amplitude Spinal Manipulation: Effect of Thrust Direction. Spine. 2018;43(1):1–9.

Reed WR, Pickar JG, Sozio RS, Liebschner MAK, Little JW, Gudavalli MR. Characteristics of Paraspinal Muscle Spindle Response to Mechanically Assisted Spinal Manipulation: A Preliminary Report. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2017;40(6):371–80.

Devecchi V, Rushton AB, Gallina A, Heneghan NR, Falla D. Are neuromuscular adaptations present in people with recurrent spinal pain during a period of remission? a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(4):e0249220.

Pagé I, Nougarou F, Lardon A, Descarreaux M. Changes in spinal stiffness with chronic thoracic pain: Correlation with pain and muscle activity. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(12):e0208790.

Lee RY, McGregor AH, Bull AM, Wragg P. Dynamic response of the cervical spine to posteroanterior mobilisation. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2005;20(2):228–31.

Ross JK, Bereznick DE, McGill SM. Determining cavitation location during lumbar and thoracic spinal manipulation: is spinal manipulation accurate and specific? Spine. 2004;29(13):1452–7.

Donaldson M, Petersen S, Cook C, Learman K. A Prescriptively Selected Nonthrust Manipulation Versus a Therapist-Selected Nonthrust Manipulation for Treatment of Individuals With Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2016;46(4):243–50.

McCarthy CJ, Potter L, Oldham JA. Comparing targeted thrust manipulation with general thrust manipulation in patients with low back pain. A general approach is as effective as a specific one. A randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2019;5(1):e000514.

Sutlive TG, Mabry LM, Easterling EJ, Durbin JD, Hanson SL, Wainner RS, et al. Comparison of short-term response to two spinal manipulation techniques for patients with low back pain in a military beneficiary population. Mil Med. 2009;174(7):750–6.

Tuttle N, Evans K, Sperotto dos Santos Rocha C. Localised manual therapy treatment has a preferential effect on the kinematics of the targeted motion segment. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2021;56:102457.

Ali MN, Sethi K, Noohu MM. Comparison of two mobilization techniques in management of chronic non-specific low back pain. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2019;23(4):918–23.

de Oliveira RF, Costa LOP, Nascimento LP, Rissato LL. Directed vertebral manipulation is not better than generic vertebral manipulation in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomised trial. J Physiother. 2020;66(3):174–9.

Gevers-Montoro C, Provencher B, Northon S, Stedile-Lovatel JP, Ortega de Mues A, Piché M. Chiropractic Spinal Manipulation Prevents Secondary Hyperalgesia Induced by Topical Capsaicin in Healthy Individuals. Front Pain Res (Lausanne, Switzerland). 2021;2:702429.

Provencher B, Northon S, Piché M. Segmental Chiropractic Spinal Manipulation Does not Reduce Pain Amplification and the Associated Pain-Related Brain Activity in a Capsaicin-Heat Pain Model. Front Pain Res (Lausanne, Switzerland). 2021;2:733727.

Watanabe N, Piché M. Editorial: Mechanisms and Effectiveness of Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Pain Management. Front Pain Res (Lausanne, Switzerland). 2022;3:863751.

Muhsen A, Moss P, Gibson W, Walker B, Jacques A, Schug S, et al. The Association Between Conditioned Pain Modulation and Manipulation-induced Analgesia in People With Lateral Epicondylalgia. Clin J Pain. 2019;35(5):435–42.

Howick J, Glasziou P, Aronson JK. Evidence-based mechanistic reasoning. J Roy Soc Med. 2010;103(11):433–41.

Haavik Taylor H, Murphy B. The effects of spinal manipulation on central integration of dual somatosensory input observed after motor training: a crossover study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33(4):261–72.

Haavik-Taylor H, Murphy B. Cervical spine manipulation alters sensorimotor integration: a somatosensory evoked potential study. ClinNeurophysiol. 2007;118(2):391–402.

Ogura T, Tashiro M, Masud M, Watanuki S, Shibuya K, Yamaguchi K, et al. Cerebral metabolic changes in men after chiropractic spinal manipulation for neck pain. Altern Ther Health Med. 2011;17(6):12–7.

Sparks C, Cleland JA, Elliott JM, Zagardo M, Liu WC. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging to determine if cerebral hemodynamic responses to pain change following thoracic spine thrust manipulation in healthy individuals. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2013;43(5):340–8.

Evans DW. How to gain evidence for causation in disease and therapeutic intervention: from Koch’s postulates to counter-counterfactuals. Med Health Care Philos. 2022;25(3):509–21.

Lascurain-Aguirrebeña I, Newham D, Critchley DJ. Mechanism of Action of Spinal Mobilizations: A Systematic Review. Spine. 2016;41(2):159–72.

Parravicini G, Bergna A. Biological effects of direct and indirect manipulation of the fascial system Narrative review. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2017;21(2):435–45.

Crane JD, Ogborn DI, Cupido C, Melov S, Hubbard A, Bourgeois JM, et al. Massage therapy attenuates inflammatory signaling after exercise-induced muscle damage. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(119):119ra13.

Degenhardt BF, Darmani NA, Johnson JC, Towns LC, Rhodes DC, Trinh C, et al. Role of osteopathic manipulative treatment in altering pain biomarkers: a pilot study. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2007;107(9):387–400.

Kovanur-Sampath K, Mani R, Cotter J, Gisselman AS, Tumilty S. Changes in biochemical markers following spinal manipulation-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2017;29:120–31.

Lohman EB, Pacheco GR, Gharibvand L, Daher N, Devore K, Bains G, et al. The immediate effects of cervical spine manipulation on pain and biochemical markers in females with acute non-specific mechanical neck pain: a randomized clinical trial. J Man Manip Ther. 2019;27(4):186–96.

Teodorczyk-Injeyan JA, McGregor M, Triano JJ, Injeyan SH. Elevated Production of Nociceptive CC Chemokines and sE-Selectin in Patients With Low Back Pain and the Effects of Spinal Manipulation: A Nonrandomized Clinical Trial. Clin J Pain. 2018;34(1):68–75.

Council GC. The Code: Standards of conduct, performance and ethics for chiropractors. GCC; 2019.

Council HaCP. Standards of Proficiency - Physiotherapists. HCPC; 2013.

Council GO. Osteopathic Practice Standards. GOC; 2023.

Therapies TCfST. GCMT Code of Practice, Ethics and Proficiency for Professional Associations. GCMT; 2023.

Daluiso-King G, Hebron C. Is the biopsychosocial model in musculoskeletal physiotherapy adequate? An evolutionary concept analysis. Physiotherapy theory and practice. 2020:1–17.

Søndenå P, Dalusio-King G, Hebron C. Conceptualisation of the therapeutic alliance in physiotherapy: is it adequate? Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2020;46:102131.

World Health Organisation. Patient Safety 2019 [Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/patient-safety#:~:text=Patient%20Safety%20is%20a%20health,during%20provision%20of%20health%20care.

Vogel S, Mars T, Keeping S, Barton T, Marlin N, Froud R, et al. Clinical Risk Osteopathy and Management Scientific Report. 2012.

Ekerholt K, Bergland A. Learning and knowing bodies: Norwegian psychomotor physiotherapists’ reflections on embodied knowledge. Physiother Theory Pract. 2019;35(1):57–69.

Hutting N, Johnston V, Staal JB, Heerkens YF. Promoting the Use of Self-management Strategies for People With Persistent Musculoskeletal Disorders: The Role of Physical Therapists. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2019;49(4):212–5.

Kongsted A, Ris I, Kjaer P, Hartvigsen J. Self-management at the core of back pain care: 10 key points for clinicians. Braz J Phys Therap. 2021.

Elwyn G, Durand MA, Song J, Aarts J, Barr PJ, Berger Z, et al. A three-talk model for shared decision making: multistage consultation process. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2017;359:j4891.

Broom B. The Practice of Whole Person-Centred Healthcare. In: Anjum RL, Copeland S, Rocca E, editors. Rethinking Causality, Complexity and Evidence for the Unique Patient: A CauseHealth Resource for Healthcare Professionals and the Clinical Encounter. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 215–26.

Darlow B, Dowell A, Baxter GD, Mathieson F, Perry M, Dean S. The enduring impact of what clinicians say to people with low back pain. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(6):527–34.

Stewart M, Loftus S. Sticks and Stones: The Impact of Language in Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018;48(7):519–22.

Lin I, Wiles L, Waller R, Caneiro JP, Nagree Y, Straker L, et al. Patient-centred care: the cornerstone for high-value musculoskeletal pain management. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(21):1240–2.

Cowell I, O’Sullivan P, O’Sullivan K, Poyton R, McGregor A, Murtagh G. Perceptions of physiotherapists towards the management of non-specific chronic low back pain from a biopsychosocial perspective: A qualitative study. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2018;38:113–9.

Edmond SN, Keefe FJ. Validating pain communication: current state of the science. Pain. 2015;156(2):215–9.

O’Keeffe M, Cullinane P, Hurley J, Leahy I, Bunzli S, O’Sullivan PB, et al. What Influences Patient-Therapist Interactions in Musculoskeletal Physical Therapy? Qualitative Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis. Phys Ther. 2016;96(5):609–22.

Copnell G. Informed consent in physiotherapy practice: it is not what is said but how it is said. Physiotherapy. 2018;104(1):67–71.

Lee A. Bolam’ to “Montgomery” is result of evolutionary change of medical practice towards ’patient-centred care. Postgrad Med J. 2017;93(1095):46–50.

Lewis J, O’Sullivan P. Is it time to reframe how we care for people with non-traumatic musculoskeletal pain? Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(24):1543–4.

Lewis J, Ridehalgh C, Moore A, Hall K. This is the day your life must surely change: Prioritising behavioural change in musculoskeletal practice. Physiotherapy. 2021.

Lewis JS, Stokes EK, Gojanovic B, Gellatly P, Mbada C, Sharma S, et al. Reframing how we care for people with persistent non-traumatic musculoskeletal pain. Suggestions for the rehabilitation community. Physiotherapy. 2021.

Bishop A, Foster NE, Thomas E, Hay EM. How does the self-reported clinical management of patients with low back pain relate to the attitudes and beliefs of health care practitioners? A survey of UK general practitioners and physiotherapists. Pain. 2008;135(1–2):187–95.

Darlow B, Fullen BM, Dean S, Hurley DA, Baxter GD, Dowell A. The association between health care professional attitudes and beliefs and the attitudes and beliefs, clinical management, and outcomes of patients with low back pain: a systematic review. Eur J Pain (London, England). 2012;16(1):3–17.

Lakke SE, Soer R, Krijnen WP, van der Schans CP, Reneman MF, Geertzen JH. Influence of Physical Therapists’ Kinesiophobic Beliefs on Lifting Capacity in Healthy Adults. Phys Ther. 2015;95(9):1224–33.

Howe LC, Leibowitz KA, Crum AJ. When Your Doctor “Gets It” and “Gets You”: The Critical Role of Competence and Warmth in the Patient-Provider Interaction. Front Psych. 2019;10:475.

Newell D, Lothe LR, Raven TJL. Contextually Aided Recovery (CARe): a scientific theory for innate healing. Chiropr Man Therap. 2017;25:6.

Rossettini G, Camerone EM, Carlino E, Benedetti F, Testa M. Context matters: the psychoneurobiological determinants of placebo, nocebo and context-related effects in physiotherapy. Arch Physiother. 2020;10:11.

Gallace A. Social Touch. In: Olausson H, Wessberg J, Morrison I, McGlone F, editors. Affective Touch and the Neurophysiology of CT Afferents: Springer; 2016.

Gallace A, Spence C. The science of interpersonal touch: an overview. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;34(2):246–59.

Kelly MA, Nixon L, McClurg C, Scherpbier A, King N, Dornan T. Experience of Touch in Health Care: A Meta-Ethnography Across the Health Care Professions. Qual Health Res. 2018;28(2):200–12.

McGlone F, Cerritelli F, Walker S, Esteves J. The role of gentle touch in perinatal osteopathic manual therapy. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;72:1–9.

Olausson H, Wessberg J, Morrison I, McGlone F. Affective Touch and the Neurophysiology of CT Afferents: Springer; 2016.

McParlin Z, Cerritelli F, Rossettini G, Friston KJ, Esteves JE. Therapeutic Alliance as Active Inference: The Role of Therapeutic Touch and Biobehavioural Synchrony in Musculoskeletal Care. Front Behav Neurosci. 2022;16:897247.

Meijer LL, Ruis C, van der Smagt MJ, Scherder EJA, Dijkerman HC. Neural basis of affective touch and pain: A novel model suggests possible targets for pain amelioration. J Neuropsychol. 2021.

Allen-Collinson J, Pavey A. Touching moments: phenomenological sociology and the haptic dimension in the lived experience of motor neurone disease. Sociol Health Illn. 2014;36(6):793–806.

Bjorbækmo WS, Mengshoel AM. “A touch of physiotherapy” - the significance and meaning of touch in the practice of physiotherapy. Physiother Theory Pract. 2016;32(1):10–9.

Nummenmaa L, Tuominen L, Dunbar R, Hirvonen J, Manninen S, Arponen E, et al. Social touch modulates endogenous μ-opioid system activity in humans. Neuroimage. 2016;138:242–7.

Calsius J, De Bie J, Hertogen R, Meesen R. Touching the Lived Body in Patients with Medically Unexplained Symptoms. How an Integration of Hands-on Bodywork and Body Awareness in Psychotherapy may Help People with Alexithymia. Front Psychol. 2016;7:253.

Gentsch A, Crucianelli L, Jenkinson P, Fotopoulou A. The touched self: Affective touch and body awareness in health and disease. Affective touch and the neurophysiology of CT afferents Springer; 2016.

Cerritelli F, Chiacchiaretta P, Gambi F, Ferretti A. Effect of Continuous Touch on Brain Functional Connectivity Is Modified by the Operator’s Tactile Attention. Front Hum Neurosci. 2017;11:368.

Tramontano M, Cerritelli F, Piras F, Spanò B, Tamburella F, Piras F, et al. Brain Connectivity Changes after Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment: A Randomized Manual Placebo-Controlled Trial. Brain Sci. 2020;10(12):969.

Øberg GK, Blanchard Y, Obstfelder A. Therapeutic encounters with preterm infants: interaction, posture and movement. Physiother Theory Pract. 2014;30(1):1–5.

Øberg GK, Normann B, Gallagher S. Embodied-enactive clinical reasoning in physical therapy. Physiother Theory Pract. 2015;31(4):244–52.

Consedine S, Standen C, Niven E. Knowing hands converse with an expressive body – An experience of osteopathic touch. Int J Osteopath Med. 2016;19:3–12.

Barbosa CD, Balp MM, Kulich K, Germain N, Rofail D. A literature review to explore the link between treatment satisfaction and adherence, compliance, and persistence. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:39–48.

Boulding W, Glickman SW, Manary MP, Schulman KA, Staelin R. Relationship between patient satisfaction with inpatient care and hospital readmission within 30 days. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(1):41–8.

Manary MP, Boulding W, Staelin R, Glickman SW. The patient experience and health outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(3):201–3.

Sherriff B, Clark C, Killingback C, Newell D. Musculoskeletal practitioners’ perceptions of contextual factors that may influence chronic low back pain outcomes: a modified Delphi study. Chiropr Man Therap. 2023;31(1):12.

Sherriff B, Clark C, Killingback C, Newell D. Impact of contextual factors on patient outcomes following conservative low back pain treatment: systematic review. Chiropr Manual Therap. 2022;30(1):20.

Mercer E, Mackay-Lyons M, Conway N, Flynn J, Mercer C. Perceptions of outpatients regarding the attire of physiotherapists. Physiother Can. 2008;60(4):349–57.

Petrilli CM, Mack M, Petrilli JJ, Hickner A, Saint S, Chopra V. Understanding the role of physician attire on patient perceptions: a systematic review of the literature— targeting attire to improve likelihood of rapport (TAILOR) investigators. BMJ Open. 2015;5(1):e006578.

Beach MC, Fitzgerald A, Saha S. White Coat Hype: Branding Physicians With Professional Attire. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(6):467–8.

Bearman G, Bryant K, Leekha S, Mayer J, Munoz-Price LS, Murthy R, et al. Healthcare Personnel Attire in Non-Operating-Room Settings. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(2):107–21.

Rehman SU, Nietert PJ, Cope DW, Kilpatrick AO. What to wear today? Effect of doctor’s attire on the trust and confidence of patients. Am J Med. 2005;118(11):1279–86.

Brady B, Veljanova I, Schabrun S, Chipchase L. Integrating culturally informed approaches into physiotherapy assessment and treatment of chronic pain: a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7):e021999.

Miles A, Mezzich JE. The care of the patient and the soul of the clinic: person-centered medicine as an emergent model of clinical practice. Int J Person Centred Med. 2012;1(2):207–22.

Cowell I, McGregor A, O’Sullivan P, O’Sullivan K, Poyton R, Schoeb V, et al. How do physiotherapists solicit and explore patients’ concerns in back pain consultations: a conversation analytic approach. Physiother Theory Pract. 2021;37(6):693–709.

Hutting N, Caneiro JP, Ong'wen MO, Miciak M, Roberts LE. Patient-centered care in musculoskeletal practice: key elements to support clinicians to focus on the person. 2021.

Caneiro JP, Roos EM, Barton CJ, O’Sullivan K, Kent P, Lin I, et al. It is time to move beyond “body region silos” to manage musculoskeletal pain: five actions to change clinical practice. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(8):438–9.

Greenhalgh T, Howick J, Maskrey N, EBM Renaissance Group. Evidence based medicine: a movement in crisis? Brit Med J. 2014;348:g3725.

Greenhalgh T, Snow R, Ryan S, Rees S, Salisbury H. Six ‘biases’ against patients and carers in evidence-based medicine. Bmc Med. 2015;13(1):200.

Loughlin M, Fuller J, Bluhm R, Buetow S, Borgerson K. Theory, experience and practice. J Eval Clin Pract. 2016;22(4):459–65.

Simpson JK, Innes S. Informed consent, duty of disclosure and chiropractic: where are we? Chiropr Man Therap. 2020;28(1):60.

Acknowledgements

N/A.

Use of any animal or human data or tissue

N/A.

Funding

No funding was received for this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and research design: RK, KJY, DWE, EL, AM, VG. Data collection: All authors. Data analysis: All authors. Writing and editing of the manuscript: All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants are co-authors. Ethical approval was not necessary.

Consent for publication

N/A.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kerry, R., Young, K.J., Evans, D.W. et al. A modern way to teach and practice manual therapy. Chiropr Man Therap 32, 17 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12998-024-00537-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12998-024-00537-0