Abstract

The deformation of three-dimensional highly polydisperse packings of frictional spheres with continuous unimodal and discrete uniform particle size distributions (PSDs) under uniaxial compression was investigated, using the discrete element method. The stress transmission and elasticity parameters, i.e., the effective elastic modulus and the Poisson’s ratio of the granular assemblies were examined; these parameters are important in many engineering disciplines. The influence of the shape of the PSD on the porosity and the transmission of pressures in samples was observed; however, the shape of the PSD did not affect the stiffness and the Poisson’s ratio of polydisperse granular packings. The results revealed that, in some cases, knowledge of the grain size distribution is not a critical issue for modeling granular packings composed of non-uniformly sized spheres.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Granular materials play important roles in the agriculture, food, pharmaceutical, cosmetics and constructions industries. Materials are subjected to technological processes, such as compression and mixing, whose design requires advanced research into granular matter. Granular packings differ from one another owing to the different material and geometric properties of particles composing beds. Material properties include density, stiffness and surface roughness, while the geometric properties of particles include their size, size distribution and shape. Each of these parameters has been found to determine the structure and the mechanical response of granular materials to external shear and compressive loads [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10].

Most granular packings involved in industrial and natural processes are related to polydispersity. Polydispersity affects the rearrangement of the particles and the contact network in granular systems, thus resulting in different compaction characteristics of particulate materials and powders, which is important in the chemical and construction industries. The degree of particle size heterogeneity affects geometric aspects of the packing characteristics and the mechanism of transmission of contact forces in granular systems [3, 11]. Voivret et al. [3] observed that increasing the degree of disorder of granules and the participation of small particles in highly polydisperse mixtures resulted in a decrease in the total number of contacts. These authors observed no effect of particle size span on the internal friction angle in highly polydisperse granular media. A numerical study on the effect of particle size polydispersity on the microstructural and micromechanical properties of granular assemblies with normal PSDs, carried out by Wiącek and Molenda [12], has shown slight changes in the solid fraction and coordination number (CN) in mixtures with particles whose diameters exhibited a standard deviation less than 40%. Authors observed greater anisotropy of the contact network and the dissipation of energy in highly polydisperse mixtures, than that of sphere packings with a small degree of sphere size dispersity.

Particle size distribution can be described by a continuous or a discrete distribution [13,14,15,16,17]. Normal and lognormal PSDs are often assumed in descriptions of the random variation that occurs in the data from many scientific disciplines [18,19,20] and in descriptions of granular materials, which are important in many industrial and natural processes (e.g., seeds, grains, sands, gravel, powders). In the majority of investigations performed on granular materials, the Gaussian (normal) or log-normal PSDs, which represent continuous unimodal symmetric and asymmetric PSDs, respectively, have been applied. Suzuki and Oshima [21], Hwang et al. [22], Roozbahani et al. [23] and our research group [7], have reported that various grain size distributions can be applied in the numerical analysis of granular packings, depending on the geometrical properties of the material and objective of the study.

Understanding the relationship between the PSD function and the microstructural and mechanical characteristics of granular packings is important in different industries in which granular materials are processed. This knowledge enables scientists and engineers to predict the mechanical response of particulate systems to loads applied during mechanical processes; this results in an increased efficiency of the process and in enhanced quality of the products.

Suzuki and Oshima [21] generated mixtures of spheres with log-normal, log-uniform, Rosin–Rammler and Andreasen (Gaudin–Schumann) PSDs to examine the relationship between the coordination number and the shape of the PSD. They reported that the CN deviated from the value obtained for a monodisperse sphere bed as the size distribution broadened; they found that an average \({ CN} \sim 6\), which is the value for a uniform-sized frictionless sphere packing. The CN was found to be independent of both the type of PSD and the degree of particle size heterogeneity. Hwang et al. [22] simulated two-dimensional packing structures composed of circular and ellipsoidal particles with normal, Rosin–Rammler and uniform PSDs. The porosity of granular packings was found to be strongly affected by the shape of PSD. For ellipsoidal particles, a uniform distribution provided the greatest porosity, while the smallest porosity was observed in mixtures with a normal distribution. Hwang et al. [22] reported that the average CN was dependent on the type of PSD, thus contradicting to findings of Suzuki and Oshima [21]. Roozbahani et al. [23] studied the effect of the PSD shape on the porosity of polydisperse sphere packings with the same size range and normal, exponential, log-normal, and random, size distributions; they found that a log-normal distribution provided the smallest porosity. In turn, they observed that samples with a random PSD exhibited the greatest porosity.

Wiącek and Molenda [7] conducted discrete element method (DEM) simulations for polydisperse packings of spheres with a small degree of particle size heterogeneity (equal to 20% of the particle mean diameter) and, with normal, log-normal, random, and uniform PSDs. Authors observed no effect of the shape of PSD on the microstructure in the packings with continuous PSDs. A uniform distribution provided a smaller solid fraction and CN than that provided by the normal distribution of diameters of spheres. The continuous distributions provided the same microstructure and micromechanical characteristics of polydisperse sphere packings; thus, the choice of the shape of a continuous PSD for DEM simulations of quasi-static processes should not be a critical issue if the micromechanical properties of the packings are considered.

Dahl et al. [14] conducted three-dimensional simulations of unbounded shear flows to investigate the stresses and granular energy in particulate systems with Gaussian and lognormal sphere size distributions. The shear stresses in mixtures were found to be similar to those predicted on the basis of monodisperse kinetic theory and that were independent of the width of the PSD. Pressures in samples decreased with an increase in degree of particle size heterogeneity; however, the shape of the PSD was not observed to affect the pressure.

A particulate assembly subjected to external loads undergoes deformations, and the bulk response of a material is strongly affected by its porosity [24]. Schöpfer et al. [24] conducted DEM simulations of confined triaxial extension and compression tests for polydisperse samples with power-law and uniform bimodal PSDs. Their results showed that the strength and angle of internal friction were strictly related to the porosities of the samples; however, they were independent of the PSD. The Young’s modulus decreased substantially with an increase in porosity and was high in packings with a power-law PSD. The Poisson’s ratio, which was independent of porosity, was high in mixtures with uniform and bimodal distributions.

A review of the literature reveals that the results of studies on the influence of the shape of the PSD on the microstructure and mechanical characteristics of granular packing are frequently inconsistent. This inconsistency may be due to the fact that the structural properties of granular packing and its mechanical behavior depend on both, the particle size polydispersity and the contact density [25,26,27]. Because the contact density is determined via a generation procedure and loading process, the order of the curves for different distributions as well as their trends may differ among various projects.

A review of the literature also reveals that the majority of investigations conducted so far has been devoted to particulate assemblages with a small degree of polydispersity and has addressed only their structure and micromechanics. No comprehensive study on the effect of the type of PSD on the structure and mechanical properties of highly polydisperse granular mixtures has been reported so far, thus resulting in a research gap. The previous studies, despite being important to engineers and technological process designers, are insufficient. Therefore, the objective of the presented project was to analyze the compression mechanics of highly polydisperse granular mixtures with various PSDs; the analyzed traits include the structural and mechanical properties of these materials at both the microscale and macroscale. The normal, log-normal and non-uniform random distribution functions were applied to compare properties of mixtures with different continuous unimodal PSDs. Investigations were also extended to ternary packings with uniform discrete PSDs. Ternary mixtures represent the simplest case of polydisperse particulate systems, which exhibit interesting behavior. Understanding such behavior could pave the way for fast and accurate interpretation of the effects observed in complex packings of non-uniformly sized grains. In some cases, multicomponent granular packings can be replaced by simple bidisperse or tridisperse samples [28], which decreases computational effort and is of interest to researchers and engineers.

2 Numerical method

Because experimental studies cannot provide detailed insights into the microstructure and micromechanical properties of particulate assemblies, numerical simulation techniques are increasingly preferred to represent granular media. In this study, discrete element simulations were performed to investigate compression mechanics of polydisperse granular packings. The DEM, which is based on a microstructural approach, is a numerical technique for investigating the mechanical behavior of particulate systems in detail [29]. In the present study, a simplified non-linear Hertz–Mindlin contact model was used.

Three continuous unimodal PSDs: normal, log-normal, and random, that were complemented by a discrete uniform distribution, were considered in this study. The first PSD is a continuous normal distribution described by the following probability density function:

where D is a random particle diameter, \(\mu \) is the mean or expectation of the distribution and \(\sigma \) is the standard deviation. A histogram of the normal distribution of the diameters of particles is shown in Fig. 1a.

The second continuous unimodal PSD is a log-normal distribution. It is represented as follows:

which is closely related to the normal distribution. A histogram of the log-normal distribution of the diameters of particles is illustrated in Fig. 1b.

The third-unimodal PSD is a continuous PSD with diameters of spheres non-uniformly and randomly sized within the range between 0.35\(D_{b}\) and 5.2\(D_{b}\), where \(D_{b }= 7.3\) mm is the diameter of a basic sphere modeled in simulations. A histogram of the random distribution of the diameters of particles is shown in Fig. 1c.

The fourth PSD is a discrete uniform distribution expressed by the following probability function:

where n is the number of fractions in the mixture. Ternary sphere packings were generated with an equal number of particles with diameters of 2, 7.3 and 12.6 mm. A histogram of the uniform distribution of diameters of particles is illustrated in Fig. 1d.

In this study, three-dimensional (3D) simulations of uniaxial confined compression of granular packings were conducted, using the EDEM package [30]. The uniaxial compression test is a common method for determining the mechanical properties of granular materials of interest to technological process designers. Both, physical [31, 32] and numerical [10, 33,34,35,36] modeling of the compression of a granular solid may provide useful scientific insight and valuable knowledge necessary for efficient design.

The uniaxial compression test enables analysis of the stress–strain characteristics of granular solids and determination of material parameters such as the lateral-to-vertical pressure ratio (k), the modulus of elasticity (E), or the Poisson’s ratio (\(\nu \)). The uniaxial compression apparatus with square cross section 0.12 m long and 0.132 m high was modeled to measure loads in two perpendicular horizontal directions x and y in a sample subjected to deformation in vertical direction z (Fig. 2). The dimensions of the sample were greater than 15 mean particle diameters (\(\bar{{D}})\) which we previously found to be a representative elementary volume for polydisperse granular assemblies [37]. Packings were composed of spheres with the same mean particle diameter (\(\bar{{D}}=7.3\,\hbox {mm}\)) and standard deviation of particle mean diameter (\(\sigma = 0.6\bar{{D}}\)). The number of particles in samples varied from 2200 for log-normal and random distributions to 2300 and 2400 for normal and uniform distributions, respectively. The spheres were simulated with the following input parameters: density \({\rho }= 1720\,\hbox {kg}/\hbox {m}^{3}\), Poisson’s ratio \(\nu = 0.26\), Young’s modulus \(Y = 560\,\hbox {MPa}\), coefficient of restitution for collisions between particles \(e_{pp}=0.21\), the coefficient of restitution for collisions between a particle and a wall of \(e_{pw }= 0.54\), a coefficient of static friction between spheres \({\mu }_{spp }= 0.4\), and the coefficient of static friction between a sphere and a wall of \({ \mu }_{spw }= 0.29\). Because the real materials exhibit some rolling strength, the coefficient of rolling friction \(\mu \)\(_{r }= 0.01\) was applied. The walls of the chamber were modeled with \({\rho }= 7800\,\hbox {kg/m}^{3}, \nu = 0.3\) and \(Y = 200\) GPa, which were material parameters of the steel.

The particles with random initial coordinates were generated in the box with a height that was twice that of the chamber of the apparatus. The spheres then settled onto the bottom of the test chamber under gravitational force which resulted in different initial anisotropies of packings. The initial configuration of the sample with normal PSDs is shown in Fig. 2. As soon as the total kinetic energy of the particles decreased to less than 10 \(^{-5}\)J, which was considered an equilibrium state, spheres were compressed through the top cover of the chamber, which was moved vertically downward at a constant velocity of 3 m/min. A maximum vertical pressure on the cover \({\sigma }_{z }= 100\) kPa was adopted in accordance with the recommendation of Eurocode 1 [38] for the measurement of solid properties of general relevance for silo design. The simulations were conducted with the time step varying from 10\(^{-7}\) to 10\(^{-5}\). Three replicate experiments were performed for each PSD to verify repeatability of the numerical tests. The coefficients of variation in the samples did not exceed 5 and 3% for the solid fraction and the average CN, respectively, which demonstrates good test repeatability.

3 Results and discussion

Figure 3 shows the span of the PSD, calculated for granular packings with various shapes of PSD. The particle size span, which is a measure of the degree of polydispersity of mixture, is defined as follows [11]:

where \(D_{\min } \) and \(D_{\max } \) are the smallest and the largest sphere diameters, respectively. The case \(s = 0\) corresponds to a monodisperse distribution, while \(s = 1\) represents an infinitely polydisperse system. The particle size span decreased from 0.73 for the assembly with a uniform PSD to 0.97 for the mixture with a log-normal distribution (Fig. 3). The difference between size spans calculated for packings with normal and uniform distributions exceeded 23%, despite the same mean diameter of spheres and standard deviation of particle mean diameter in these mixtures.

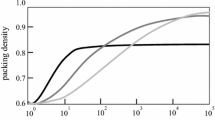

The evolution of porosity (\(\varPhi \)) in mixtures with various PSDs when the mixtures were subjected to compressive loads is shown in Fig. 4. The mean values are shown along with error bars that indicate \(\pm 1\,{ s.d.}\) Mixtures with normal, log-normal, and random PSDs exhibited similar initial porosities. The uniform distribution provided greater porosity than the continuous PSDs; however, the difference in \(\varPhi \) values calculated for a ternary sample and for one with Gaussian PSD function did not exceed 3%. The porosity decreased sharply at low vertical stresses that resulted from initial fast consolidation of loose sample because of the rearrangement of particles and the filling of empty pores between spheres. For high compressive loads, less or no particle rearrangements occured in mechanically stable samples and a slow monotonic decrease in porosity was observed. For a vertical pressure of 100 kPa, the porosity was the smallest in assemblies with log-normally and randomly distributed diameters of particles. The \(\varPhi \) values increased by more than 3 and 7% in packings with normal and uniform PSDs, respectively, which corroborates previous findings reported by Hwang et al. [22] for two-dimensional packings of circular particles. These results are in partial agreement with those previously reported by authors for mixtures with a small degree of polydispersity (\(\sigma =\) 0.2\(\bar{{D}})\) [7], where the authors observed a slight differences between densities of packings with continuous PSDs in the examined mixtures. A decrease of few percent in the packing density was observed in mixtures with a discrete uniform PSD, as compared with the packing density in samples with continuous PSDs. These findings suggest that the degree of polydispersity may determine differences between densities of packings with various PSDs.

The shape of the PSD function slightly influenced the average CN, which represents the number of contacts in a sample per number of particles. Figure 5 shows the evolution of the average CN in samples with different PSDs subjected to compressive loads. The results indicate that the differences in CN values for various PSD functions lie within the range of scatter. This result corroborates our previous findings [7] and those of Suzuki and Oshima [21] who observed negligible differences between the average CNs in packings of spheres with various continuous PSDs. We observed smaller CNs in samples with a small degree of particle size heterogeneity and a discrete uniform PSD than the CNs calculated for continuous PSDs [7]. This effect was not observed in the present study, which suggests that the influence of the type of PSD on the average CN can be determined by the degree of particle polydispersity.

The compression process was observed in the present study to comprise two stages, which is consistent with the observations of Duberg and Nyström [39], Sheng et al. [40] and Frenning [41]. In the first stage of compression, for compressive pressures lower than 15 kPa, the perturbation of the top layer of particles due to loads exerted by the cover of the chamber induced substantial changes in particle positions and in interparticle contacts. The CN decreased because of rearrangements of spheres without the formation of stable contacts. The average CNs reached minima lower than 3 for the log-normal, random, and uniform distributions, which corroborates the findings of Sheng et al. [40] and Frenning [41]. The first stage continued until the particles began to assume spatially frustrated configurations. The system reached a state where its capacity to rearrange was exhausted and where particles were locked by structurally stable contacts with neighboring particles. On reaching that state, any further decrease in porosity of granular packing might result only from deformation of elastic spheres under increasing applied load. In the second stage of the compression process, new stable contacts were formed and a rapid increase in the CN was observed.

The degree of mobilization of friction at the sphere-to-sphere contacts was examined for granular packings with different PSD functions. The friction was considered to be fully mobilized when the average ratios of tangential and normal contact forces (\(F^{t}/F^{n})\) equaled the coefficient of static friction between spheres, which was 0.4 in these simulations. The average value of \(F^{t}/F^{n}\) was 0.195 for the uncompressed polydisperse assembly with a normal PSD; this value increased by more than 28% for mixtures with log-normal and random PSDs (Fig. 6). The average value of \(F^{t}/F^{n}\) was nearly 17% higher in the ternary sample, as compared to packing with the Gaussian PSD function. In uncompressed packings, the shape of the PSD was found to affect the degree of mobilization of friction at the point of contact between particles; however, no influence of the PSD type on mobilization of friction was observed in sphere packings under a vertical pressure of 100 kPa (Fig. 6). These results are in agreement with those of our previous findings for mixtures with small degree of particle size polydispersity [7]. However, in the packings examined in the present study, mobilization of friction differed for various continuous PSDs.

At low compressive loads, stronger anisotropy effects and a greater contribution of the nonaffine motions, which are affected by the PSD, may be observed [42], thus resulting in different \(F^{t}/F^{n}\) values. The approximate average values of \(F^{t}/F^{n}\) at high compressive loads in all of the simulated packings was strictly related to approximately the same percentage contribution of contacts with nearly fully mobilized friction (\(F^{t}/F^{n}> 0.38\)) in all of the samples.

At low vertical pressures, a sharp increase in the average ratio of tangential-to-normal contact forces was observed because of the rearrangement of particles in the sample, which was followed by a weak increase in \(F^{t}/F^{n}\) values in mechanically stable samples at great compressive loads. The evolution of the average \(F^{t}/F^{n}\) value with imposed compressive loads for sphere packings with a normal PSD is shown in the inset of Fig. 6.

The stress–strain relationships for lateral and horizontal pressures in the examined packings are plotted in Fig. 7. Three PSD-s were selected to simplify the figure. Samples with a uniform PSD were less compressible than mixtures with continuous PSDs. In packings with normal and random PSDs, the vertical and horizontal stresses reached maxima at relative strains that were larger by 10 and 17%, respectively, than the maximal stresses of mixtures with a uniform distribution. However, in the whole range of stress, the differences between relative strains calculated for various PSDs were within the range of scatter.

The elastic response of highly polydisperse granular packings to a compressive load was examined in this study using the definition of effective elastic modulus taken from Eurocode 1 [38], which is represented as follows:

where H is the height of the assembly, \({\varDelta \sigma }_{z}\) is the change in vertical pressure during each time step, \({\varDelta u}_{z}\) is the change in vertical displacement, and \(k_{L}\) is the ratio of the change in lateral pressure to the change in vertical pressure during each time step. The equation for effective elastic modulus was derived from Hook’s law under the assumption of linear elasticity and isotropy of the medium. The stress tensor has been given in terms of a strain tensor, on the basis of the theory of elasticity [43]; however, the traditional theory of elasticity in soil mechanics requires crude assumptions that neglected discontinuity, non-homogeneity, or elasticity of real assemblies. Further assumptions include rigidity of container walls, symmetry of wall loads, and constancy of the lateral-to-vertical pressure ratio.

Figure 8 shows the evolution of E under an imposed compressive load in mixtures with various PSD functions. The effective elastic moduli of polydisperse granular packings increased with increasing compressive loads because of a decrease in porosity of the sample, which is consistent with the results presented by Schöpfer et al. [24]. These authors also reported that the elasticity of polydisperse mixtures was affected by PSD. In the current study, no effect of the shape of PSD on stiffness of samples was observed. High variation of the E values was observed, which was probably a result of a nonreplicable spatial structure of the randomly generated assemblies.

The lateral-to-vertical pressure ratio (k), which is defined as the ratio of horizontal pressure in the x direction to the vertical pressure (see Fig. 2), was calculated for polydisperse samples with different PSD functions. Figure 9 shows the evolution of the pressure ratios with imposed compressive load in the simulated mixtures. Similar to the porosity, the k values decreased sharply because of rearrangement of particles during initial fast consolidation of the sample at vertical stresses up to \(\sim \) 20 kPa. Further gradual mobilization of friction in points of contact between particles with increasing vertical pressure resulted in a slight change in the k values. For a vertical pressure of 100 kPa, the k value was the highest in the mixture with the normally distributed diameters of spheres. A 6% decrease in the pressure ratio in the ternary sample and a greater than 10% decrease in packings with log-normal and random PSD functions were, probably related to the initial values of \(F^{t}{/}F^{n}\), which determined the transmission of pressures through the compressed particulate system. The inset of Fig. 9 shows the k values estimated for polydisperse samples with different PSDs for a vertical load of 100 kPa.

On the basis of the theory of elasticity, when an elastic material is subjected to confined uniaxial deformation, the Poisson’s ratio (\(\nu \)) can be expressed as a function of k [44] as follows:

Because the Poisson’s ratio of a material is related to its elastic modulus [43], which was approximated for all of the samples, slight differences in \(\nu \) values in packings with various PSDs were observed (Fig. 10).

Figure 11 shows the evolution of the Poisson’s ratio in samples with different PSD functions when the samples were subjected to compressive loads. For most common materials the Poisson’s ratio is in the range 0–0.5, while perfectly incompressible materials have a Poisson’s ratio of 0.5.

The Poisson’s ratio decreased sharply at small vertical pressures, which was followed by a slow decrease at vertical pressures greater than 20 kPa. Because the Poisson’s ratio is a function of the lateral-to-vertical pressure ratio and the latter one was found to be determined by the porosity of the material, the porosity dependence of the Poisson’s ratio is evident. These results contradict the findings of Schöpfer et al. [24], who found that the Poisson’s ratio was independent of porosity.

At low compressive loads, large differences in elastic response of the mixtures with various PSDs were observed. These differences were probably caused by stronger anisotropy effects and greater contribution of the nonaffine motions affected by PSD [42].

4 Conclusions

In this study, the compression mechanics of polydisperse granular mixtures with different PSDs was examined. 3D discrete element simulations of uniaxial compression test were conducted for highly polydisperse packings composed of spheres with normally, log-normally, randomly and uniformly distributed diameters of particles. The mean particle size and standard deviation of the particle mean diameter (0.6\(\bar{{D}})\) were set to be the same in all of the samples.

The analyzed parameters included porosity, number of contacts, and degree of mobilization of friction at the sphere-to-sphere contacts, which enabled a detailed interpretation of the effects observed in polydisperse mixtures at the macroscale. Behaviors studied macroscopically included the transmission of pressures in particulate assemblies and the evolution of elastic parameters (effective elastic modulus and the Poisson’s ratio) with imposed compressive loads.

The porosity of samples decreased sharply at low vertical stresses because of the rearrangement of particles and the filling of empty pores between spheres during the initial fast consolidation of loose samples. At high compressive loads, weak or no particle rearrangements in mechanically stable samples occurred and a monotonic decrease in porosity was observed. Changes in the lateral-to-vertical pressure ratio and the Poisson’s ratio in samples subjected to external loads were strictly related to changes in porosities of packings. Coordination number, effective elastic modulus, and degree of mobilization of friction in contacts between particles also showed relationships with the structure of particulate assemblages. Substantial differences in the values of parameters calculated for samples with normal and log-normal PSDs were observed, despite the close relation between these two distribution functions. Contrary to expectations, the microstructural and mechanical properties of mixtures with log-normal PSD were similar to properties of packing with a random PSD.

This study has shown that the shape of the PSD affected the porosity and transmission of pressures in highly polydisperse granular assemblies subjected to compressive loads; however, the average CN and the elastic parameters were found to be independent of the PSD function. The results revealed that, in some cases, knowledge of the grain size distribution is not a critical issue for modeling granular packings composed of non-uniformly sized spheres.

Because typical granular materials involved in industrial and natural processes can be described by various PSD functions, the scientific outcomes from this project should find wide application in research investigation granular mechanics and in the design of processes, in which particulate mixtures participate.

References

Zhang, Y.M., Napier-Munn, T.J.: Effects of particle size distribution, surface area and chemical composition on Portland cement strength. Powder Technol. 83, 245–252 (1995)

O’Sullivan, C., Bray, J.-D., Riemer, M.-F.: Influence of particle shape and surface friction variability on response of rod-shaped particulate media. J. Eng. Mech. 128, 1182–1192 (2002)

Voivret, C., Radjaï, F., Delenne, J.-Y., El Youssoufi, M.-S.: Multiscale force networks in highly polydisperse granular media. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 188001 (2009)

Shaebani, M.R., Madadi, M., Luding, S., Wolf, D.E.: Influence of polydispersity on micromechanics of granular materials. Phys. Rev. E 85, 011301 (2012)

Kumar, N., Imole, O.I., Magnanimo, V., Luding, S.: Effects of polydispersity on the micro-macro behawior of granular assemblies under different deformation paths. Particuology 12, 64–79 (2014)

Wiącek, J., Molenda, M., Horabik, J., Ooi, J.Y.: Influence of grain shape and intergranular friction on material behavior in uniaxial compression: experimental and DEM modeling. Powder Technol. 217, 435–442 (2012)

Wiącek, J., Molenda, M.: icrostructure and micromechanics of polydisperse granular materials: effect of the shape of particle size distribution. Powder Technol. 268, 237–243 (2014)

Marczewska, I., Rojek, J., Kačianauskas, R.: Investigation of the effective elastic parameters in the discrete element model of granular material by triaxial compression test. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 16, 64–75 (2016)

Parafiniuk, P., Wiącek, J., Bańda, M., Molenda, M.: Pressure distribution in an assembly of wooden cylinders with various aspect ratios under uniaxial compression. Granul. Matter. 8, 2 (2016)

Wiącek, J., Stasiak, M., Parafiniuk, P.: Effective elastic properties and pressure distribution in bidisperse granular packings: DEM simulations and experiment. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 17, 271–280 (2017)

Voivret, C., Radjaï, F., Delenne, J.-Y., El Youssoufi, M.-S.: Space-filling properties of polydisperse granular media. Phys. Rev. E 6, 021301 (2007)

Wiącek, J., Molenda, M.: Effect of particle polydispersity on micromechanical properties and energy dissipation in granular mixtures. Particuology 16, 91–99 (2014)

Latham, J.-P., Munijza, A., Lu, Y.: On the prediction of void porosity and packing of rock particulates. Powder Technol. 125, 10–27 (2002)

Dahl, S.-R., Clelland, R., Hrenya, C.M.: Three-dimensional, rapid shear flow of particles with continuous size distributions. Powder Technol. 138, 7–12 (2003)

Durán, O., Kruyt, N.P., Luding, S.: Analysis of three-dimensional micro-mechanical strain formulations of granular materials: evaluation of accuracy. Int. J. Solids Struct. 47, 251–260 (2010)

Gardiner, B.-S., Tordessilas, A.: Effects of particle size distribution in a three-dimensional micropolar continuum model of granular media. Powder Technol. 161, 110–121 (2006)

Desmond, K.W., Weeks, E.R.: Influence of particle size distribution on random close packing of spheres. Phys. Rev. E 90, 022204 (2014)

Limpert, E., Stahel, W.-A., Abbt, M.: Log-normal distributions across the sciences: keys and clues. Bioscience 51, 341–352 (2001)

DiPietro, R.-S., Johnson, H.-G., Bennett, S.-P., Nummy, T.-J., Lewis, L.-H., Heiman, D.: Determining magnetic nanoparticle size distributions for thermomagnetic measurements. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 222506 (2010)

Sørenson, M.: On the size distribution of sand. Preprint No. 2006-3, Department of Applied Mathematics and Statistics, University of Copenhagen (2006)

Suzuki, M., Oshima, T.: Co-ordination number of a multi-component randomly packed bed of spheres with size distribution. Powder Technol. 44, 213–218 (1985)

Hwang, K.J., Wu, Y.S., Lu, W.M.: Effect of size distribution of spheroidal particles on the surface structure of a filter cake. Powder Technol. 91, 105–113 (1997)

Roozbahani, M.M., Huat, B.B.K., Asadi, A.: The effect of different random number distributions on the porosity of spherical particles. Adv. Powder Technol. 24, 26–35 (2013)

Schöpfer, M.P.J., Abe, S., Childs, C., Walsh, J.J.: The impact of porosity and crack density on the elasticity, strength and friction of cohesive granular materials: insights from DEM modeling. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 46, 250–261 (2009)

Goldenberg, C., Goldhrish, I.: Friction enhance elasticity in granular solids. Nature 433, 188–191 (2005)

Shaebani, M.R., Unger, T., Kertész, J.: Unjamming of granular packings due to local perturbations: stability and decay of displacements. Phys. Rev. E 76, 030301(R) (2007)

Shaebani, M.R., Unger, T., Kertész, J.: Unjamming due to local perturbations in granular packings with and without gravity. Phys. Rev. E 76, 030301(R) (2007)

Dutt, M., Elliott, J.M.: Granular dynamics simulations of the effect of grain size dispersity on uniaxially compacted powder blends. Granul. Matter 16, 243–248 (2014)

Cundall, P.A., Strack, O.D.: A discrete element model for granular assemblies. Géotechnique 29, 47–65 (1979)

EDEM Software (2016). www.dem-solutions.com/software/ edem-software

Rusinek, R., Molenda, M., Sykut, J., Pits, N., Tys, J.: Uniaxial compression of rapeseed using apparatus with cuboid chamber. Acta Agrophys. 10, 677–685 (2007)

Sawicki, S.: Elasto-plastic interpretation of oedometric test. Arch. Hydro Eng. Environ. Mech. 41, 111–131 (1994)

Hentz, S., Donzé, F.V., Daudeville, L.: Discrete element modeling of concrete submitted to dynamic loading at high strain rates. Comput. Struct. 82, 2509–2524 (2004)

Skrinjar, O., Larrson, L.P.: On discrete element modelling of compaction of powders with size ratio. Comput. Mater. Sci. 31, 131–146 (2004)

Azadi, P., Farnood, R., Yan, N.: Discrete element modeling of the mechanical response of pigment containing coating layers under compression. Comput. Mater. Sci. 42, 50–56 (2008)

Thornton, C.: Numerical simulations of deviatronic shear deformation of granular media. Géotechnique 50, 43–53 (2000)

Wiącek, J., Molenda, M.: Representative elementary volume analysis of polydisperse granular packings using discrete element method. Particuology 27, 88–94 (2016)

Eurocode 1. Actions on Structures. Part 4. Silos and Tanks. EN 1991–4 2006 (2006)

Duberg, M., Nyström, C.: Studies on direct compression of tablets. XVII. Porosity-pressure curves for the characterization of volume reduction mechanisms in powder compression. Powder Technol. 46, 67–75 (1986)

Sheng, Y., Lawrence, C.J., Briscoe, B.J., Thornton, C.: Numerical studies of uniaxial powder compaction process by 3D DEM. Eng. Comput. 21, 304–317 (2004)

Frenning, G.: Compression mechanics of granule beds: a combined finite/discrete element study. Chem. Eng. Sci. 65, 2464–2471 (2010)

Shaebani, M.R., Boberski, J., Luding, S., Wolf, D.E.: Unilateral interactions in granular packings: a model for the anisotropy modulus. Granul. Matter. 14, 265–270 (2012)

Landau, L.D., Lifshitz, E.M.: Theory of Elasticity. Pergamon Press, Oxford (1970)

Molenda, M., Stasiak, M.: Determination of the elastic constants of cereal grains in a uniaxial compression test. Inter. Agroph. 16, 61–65 (2002)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wiącek, J., Molenda, M. Numerical analysis of compression mechanics of highly polydisperse granular mixtures with different PSD-s. Granular Matter 20, 17 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10035-018-0788-z

Received:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10035-018-0788-z