Abstract

In this study, the discrete element method was used to examine the structural properties and geometric anisotropy of polydisperse granular packings with discrete uniform particle size distributions. Confined uniaxial compression was applied to granular mixtures with different particle size fractions. The particle size fraction (class) was defined as the fraction of the sample composed of particles with a certain size. The threshold value of number of particle size fractions (i.e., the value above which structural properties of assemblies remain constant) was determined. The effect of heterogeneity in particle size on the critical value of number of particle size fractions was investigated for packings with different ratios between diameters of the largest and smallest grains. The threshold number of particle size classes decreased from five to three as the diameter ratio between the largest and smallest grains increased. Regardless of the diameter ratio, the critical number of particle size fractions (above which the packing density and coordination number of the granular mixtures remained constant) was determined to be five. The study has also shown an increase in packing density of binary mixtures with particle size ratio increasing up to 2.5, which was followed by decrease in density of mixtures with larger particle size ratios, which has not so far been reported in the literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Granular materials are known to have wide ranges of structural and mechanical properties. Real granular packings are nonuniform in size and characterized by a certain degree of polydispersity. The high number of particulate assemblies involved in the industrial and natural processes contains components varying with both, material and geometric properties. The properties can be derived from the geometry of a solid body or particle and strongly affect the mechanical behavior of materials subjected to industrial processes (e.g., mixing, segregation, loading, and shearing) [1,2,3,4]. Granular solids are disperse systems in which particles are surrounded by a continuous medium [5], and they can be characterized by their particle sizes and divided into particle size fractions. In disperse systems, the bulk density and porosity depend on the particle size [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Wiącek conducted experimental and numerical studies on granular assemblies composed of uniform spherical particles and found that density decreased with an increase in the particle size [13]. Wiącek also reported larger average coordination numbers in monodisperse samples with smaller particles, because the packing density affected the contacts between particles. McGeary [6] and Rassously [8] demonstrated that for binary mixtures of spherical particles with equal volume fractions of particles but different particle sizes, the density increased with a decrease in size of smaller particles. Wiącek et al. studied the microstructural and micromechanical properties of granular assemblies with discrete, uniform particle size distributions (PSD) divided into three, five and seven particle size classes [14]. They found that the packing density of samples with a particle size ratio of 1.25 decreased substantially when the number of particle size fractions increased from three to seven; in contrast, this phenomenon was not observed in mixtures with larger particle size ratios. Based on these observations, Wiącek et al. suggested the existence of a certain value of particle size ratio between 1.25 and 2.5, below which the packing density decreases substantially with an increase in the particle size ratio.

Granular mixtures are involved in many industrial processes (e.g., milling, fragmentation, agglomeration, and sieving). These processes can generate systems with large particle size ratio, thereby affecting the geometric and mechanical properties of materials. An experimental study conducted by Lade et al. [15] and a numerical study prepared by Shire et al. [16] for binary packings with an equal volume fraction of particles of different sizes have shown a significant increase in density of samples with particle size ratios increasing up to seven. In mixtures with larger particle size ratios, small particles fit easily within the pores between large particles, thereby increasing the packing density. Jalali and Li [17] conducted molecular dynamics simulations of packings with bimodal discrete PSD and the ratio between diameters of the largest and smallest particles increasing to 2.5. They revealed larger densities of mixtures with greater particle size ratios. For binary mixtures, Sánchez et al. [18] observed a decrease in the global coordination number and a change in partial coordination number when the size of the smaller particle size fraction decreased. Authors observed that, contrary to the coordination number for contacts between large particles, the number of contacts between small spheres decreased with increasing differences between diameters of particles.

The mechanical properties and compaction characteristics of polydisperse materials have been extensively studied because, in granular systems, particle rearrangement and contact networks are determined by the degree of heterogeneity in particle size [12, 19]. Wiącek et al. [19] numerically studied the effect of particle size ratio on geometric anisotropy in binary sphere packings. They observed larger anisotropy in the contact normal orientation in samples with larger difference between the diameters of the large and small particles. In a study of systems with continuous PSD, Wiącek and Molenda found that polydisperse packings had more homogeneous distributions of contact force orientations than monodisperse packings [12]. These findings suggest that in polydisperse samples, the number of particle size fractions determines the distribution of contact angles. The authors also suggested the existence of a certain number of particle size classes above which the anisotropy of the contact normal orientation decreases with an increasing degree of polydispersity.

In multicomponent particulate systems, the PSD can be described by various distribution functions that strongly affect the structural properties of the material [7, 11, 14, 20]. PSDs can generally be divided into continuous and discrete distributions. Wiącek and Molenda [12] reported significant differences between the geometric properties of mixtures with the same standard deviation of mean particle diameter, described by continuous and discrete uniform PSDs. Mixtures with continuous distributions exhibited the same microstructural characteristics, whereas discrete uniform distributions exhibited smaller packing densities and average coordination numbers than systems with continuous PSDs. For continuous distributions, normal and log-normal ones are the most frequently used to describe the particulate assemblies; however, other distributions (e.g., exponential, uniform and arbitrary) may be also applied to characterize the PSDs in granular materials. Granular materials with discrete PSDs can be composed of a variety particle size fractions (e.g., two, three, or more). A higher number of particle size classes indicated a higher degree of complexity and makes interpreting the materials’ characteristics more difficult. Numerous studies have focused on bimodal particulate beds, which are the simplest example of a polydisperse granular material [6, 13, 16,17,18,19, 21, 22], along with systems composed of three or four particle size fractions [6, 14, 23,24,25,26,27]. These studies provided valuable knowledge related to the structural and mechanical properties of polydisperse granular materials. In practical applications, mixtures of granular materials are generally defined in terms of their volume fractions; therefore, most studies on granular packings with discrete PSDs have focused on assemblies with different volume fractions. The effect of particle size ratio on packing density for granular mixtures with equal volume fractions of two, three and four components is shown in Fig. 1 [23]. For binary mixtures, the packing density increased significantly with an increase in the particle size ratio, up to a particle size ratio of nearly 50. The packing density then remained constant when particle size ratio increased further. For ternary mixtures, the change in density with particle size ratio occurred more slowly than in binary samples, and the density increased throughout the entire range of particle size ratios. For particle size ratio \(> 100\), the density was larger in ternary mixtures than in binary mixtures. Increasing the number of particle size classes to four further decreased the rate of change in packing density with the increasing particle size ratio. The density of packings with the particle size ratios \(< 10\) decreased significantly with an increase in the number of particle size fractions in system. For very large particle size ratios, the packing densities of the samples containing three- and four-sized fractions were similar. Figure 1 suggests the existence of a critical number of particle size fractions above which the structural properties of particulate system remain unchanged.

Modified after Furnas [23]

Effect of particle size ratio (large:small) on the packing density in samples composed of two, three and, four particle size fractions

While extensive studies have evaluated the effect of particle size ratio on the properties of particulate beds with discrete PSDs, these studies primarily focused on binary and ternary mixtures with different volume fractions of particles with various sizes. Relatively few studies have examined the geometric properties of granular mixtures with discrete PSD uniform by a number of particles that are also found in industrial applications. These rare mixtures represent interesting systems with largerly unknown properties.

In this study, discrete element method (DEM) was used to evaluate the structural properties of granular mixtures with an equal number of fractions of different sizes. The objective was to identify the critical number of particle size fractions above which the structural properties of the system remain constant. The effect of the particle size ratio on this critical value was also investigated. The critical number of particle size classes is of interest to researchers who model processes involving particulate assemblies along with industries where the PSDs and compositions of mixtures affect the properties of their final products. The results of this paper will help scientists and engineers to optimize industrial processes that involve grain assemblies composed of multiple particle size fractions.

2 Numerical methodology

In the recent time, numerical modeling has been used to study various applications of particulate assemblies because experimental methods cannot provide detailed information about the structural and micromechanical properties of granular materials. DEM [28], the method employed in this study, provides a way to investigate the microstructures and micromechanics of granular beddings. Three-dimensional simulations were conducted using the EDEM package [29] with a simplified version of the viscous-elastic non-linear Hertz-Mindlin contact model [13]. The interactions between particles were characterized using the soft-contact approach, in which particles overlap locally at contact points.

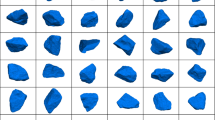

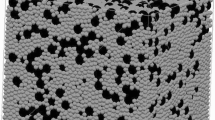

Monodisperse and polydisperse samples with the uniform discrete PSDs (characterized by an equal number of particles of different sizes in the sample \(N_{f})\) and different numbers of particle size classes were generated for the simulations. Two parameters were introduced to characterize the samples: (1) the particle size ratio (g), defined as the ratio of diameter of the largest grains in sample to the diameter of the smallest grains in sample and (2) the number of particle size fractions (n). To facilitate comparison among systems, one size fraction in all simulated assemblies was composed of spheres with diameters of 6 mm (\(D_{l}\)). The diameters of the smallest particles (\(D_{s}\)) were chosen so that g ranged between 1.25 and 5. In binary beddings with \(g > 2.5\), small particles percolate downwards between large grains [30] and may not be trapped in the tetrahedrons and octahedrons formed by larger spheres [31]; thus, granular mixtures with values of g both larger and smaller than 2.5 were examined. The differences between the diameters of spheres in neighboring size classes were consistent in simulated systems. Figure 2 shows the PSD histograms of mixtures with \(g = 5\) and different n. The total numbers of particles in the systems varied from 9400 to 21,600; however, the system volume (\(\sim 1400~\hbox {cm}^{3}\)) and the volume of the solid fraction (\(\sim 800~\hbox {cm}^{3}\)) were the same. Table 1 presents the values of Ds and \(D_{l}\) for each value of g for the simulated systems. The values of \(N_{f}\) along with volume fractions of particles with given diameter in samples (\(V_{f}\)) for different values of g are presented in Table 2. Table 3 provides the DEM input parameters used in the simulations.

The numerical procedure included two stages: sample preparation and a uniaxial confined compression test. During sample preparation, particles with random initial coordinates were generated inside rectangular box with dimensions of \(0.12~\hbox {m} \times 0.12~\hbox {m}\) and a thickness of 0.1 m, which was then placed above the chamber of uniaxial compression apparatus with the same dimensions. The chamber was equipped with rigid, frictional walls that did not deform under the applied load. The sample size referred to the representative elementary volume of polydisperse granular beddings, as established by Wiącek and Molenda [32]. The particles were allowed to settle down under gravity, generating the sample. When a state of equilibrium was reached, the granular bedding was uniaxially compressed by the top cover of the chamber, which moved vertically downward at a constant velocity of 3 m/min. Based on an internationally accepted procedure [33], the maximum vertical pressure on the top cover was 100 kPa. Three replicate tests were performed for each sample to verify repeatability.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Particle size polydispersity

The effects of g and n on the polydispersity of the granular beddings were statistically analyzed. Increasing g from 1.25 to 5 resulted in an decrease in the mean particle diameter from 5.4 to 3.6. Figure 3 shows the standard deviation of particle mean diameter (s.d.) for different values of n and g ranging from 1.25 to 5. Regardless of the g value, the s.d. decreased by more than 50% with an increase in n from 2 to 9. The largest decrease in s.d. (nearly 30%) was observed when n increased from 2 to 3. Upon a further increase in the value of n to 5, s.d. decreased by 14%. Each subsequent increase in n decreased the degree of particle size heterogeneity to a lesser degree. The difference between the s.d. values calculated for mixtures with \(n=7\) and 9 did not exceed 3%.

3.2 Packing density

Figure 4 presents the initial packing density for different values of n and g. For \(\hbox {g} < 2.5\), the packing density decreased with an increase in the value of n, while the differences between sample densities decreased as the degree of heterogeneity in the mixtures increased. Surprisingly, the densities of samples with \(g = 1.25\) and \(n > 2\) were smaller than those for monodisperse assemblies of spheres. Additional simulations were conducted for \(1.25< g < 2.5\) to determine the value of g below which the packing density of multicomponent mixtures was smaller than the density of sample composed of uniformly sized spheres. The inset of Fig. 4 suggests that \(g=1.67\) can be considered as the threshold value. Figure 4 shows that packing densities of samples with \(g \le 2.5\) was maximized at \(n = 2\) and packing density decreased significantly with increasing n. In contrast, for \(g > 2.5\), the packing density at \(n= 2\) was smaller compared with those of more complex mixtures.

The packing density of binary samples at different values of g is shown in Fig. 5. For \(\hbox {g} < 2.5\), the packing density increased with an increase in the value of g. In these mixtures, small spheres filled the pores between larger particles. Further increasing g beyond 2.5 resulted in a decrease in \(\varphi \), because of only partially filled the pores between larger particles by significantly smaller spheres. These results agree with the findings by Jalali and Li [17] related to binary mixtures with uniform discrete PSDs and \(g \le 2.5\). Mc’Geary [6] and Rassously [8], who conducted experimental and numerical studies on binary mixtures with uniform volume fractions of components, found that the packing density of samples increased by increasing g well above 2.5. Compared to mixtures with a uniform number of fractions of components, more numerous small particles are able to fully fill voids between larger spheres in packings with uniform volume fractions of components, resulting in greater packing density. The largest increase in packing density with increasing g value was observed at \(g < 10\), which supports the previous findings of Furnas (see Fig. 1) [23].

Figure 5 shows the packing densities at different values of g for mixtures with \(n=3\) and 9. The values of \(\varphi \) were larger for ternary packings compared to the packings with \(n = 9\). The packing densities increased significantly with increasing g up to value of 3.75; further increase in g resulted in slight increase in \(\varphi \) value. The differences between the densities of sphere packings with \(g \ge 2.5\) fell within the range of scattering. Figures 4 and 5 indicate that when \(g \ge 2.5\), g had no effect on the packing density of granular packings with \(n > 2\). The results indicate that the packing densities of granular materials with uniform PSD based on particle number are not sensitive to the degree of heterogeneity in particle size. The above results agree with the findings of Wiącek and Molenda [12] regarding granular packings with normal PSD. Figure 4 shows that the threshold value of n, above which the packing density remains constant, is determined by the particle size ratio. Although the particle size distribution became more homogeneous with increasing n, the critical number of particle size fractions for packing density decreased with an increase in n. For \(g < 2.5\), \(n = 5\) was identified as the critical value; however, for granular packings with \(g > 2.5\), a critical value is \(n = 3\).

3.3 Average coordination number

Figure 6 shows the average coordination number as a function of g for granular packings, under a vertical pressure of 100 kPa. Although the packing density increased (Fig. 5), the coordination number decreased by approximately 15% as a g increased from 1.25 to 2.5. A further increase in g to 5 resulted in a nearly 5% decrease in CN. In granular packings with small g, ordered structures were formed by similarly sizes particles and each particle was supported by several neighboring particles and supported other particles, resulted in larger CN. Because the polydispersity prevented the formation of a more ordered structure, in more heterogeneous mixtures with larger g, small spheres partially filled the pores between larger particles, resulting in smaller average coordination numbers. These results are in agreement with the findings of Göncü et al. [10] and Wiącek and Molenda [12], who reported fewer contacts between particles in mixtures with greater degrees of polydispersity.

Distributions of contact normal orientations in granular packings with different values of n and g, under compressive load of 100 kPa. Solid lines are harmonic fits according to Eq. (1)

The evolution of the effect of n on average coordination number in mixtures with \(g = 1.25\) provided interesting results. In samples with \(n = 9\), the CN was more than 5% lower than that of mixtures with \(n = 2\) (inset of Fig. 6). The CN(g) curves exhibit similar trends to the \(\varphi (g)\) curves, indicating that in mixtures with \(g<1.46\), the number of contacts was determined primarily by the packing density. In mixtures with g values of 2.5 and 5, an increase in particle size fractions from 2 to 3 resulted in an increase in average coordination number by 6% and 10%, respectively, despite a decrease in packing density of samples. The medium-sized particles in ternary samples decreased differences between sizes of contacting particles, producing denser contact networks. Further increasing n slightly affected the number of contacts in examined mixtures; thus, \(n = 3\) was established as the threshold value above which CN remained constant.

3.4 Geometric anisotropy

Figure 7 shows the distributions of contact normal orientations in compressed granular packings with different values of n and g. The contact angle (\(\theta \)) was defined as the ratio between the z and x components of the contact normal force. The distribution function of the contact orientation can be fitted by harmonic approximation corresponding to the second terms of the Fourier expansion of \(P(\theta )\)

where a is a measure of the degree of anisotropy, and \(\theta _n \) indicates the principal direction of anisotropy. The probability of the contact orientations \(P\left( \theta \right) \) is given by

where N is the total number of particles. Figure 8 displays the degree of contact orientation anisotropy as a function of n for samples with various values of g, when subjected to a vertical load of 100 kPa. Heterogeneous distributions of contact angles with a preference for the vertical and horizontal directions were observed in monodisperse samples, in which ordered structures were formed by uniformly sized particles. The prevalence of contact normals directed vertically and horizontally was also observed in binary packings, that increased with increasing g. In all packings with \(g = 1.25\), in which particles were arranged in a nearly crystalline formation, the vertical contact direction prevailed and degree of contact orientation anisotropy changed slightly with increasing n. For samples with \(g > 1.25\), degree of anisotropy in the distribution of contact angles decreased with increasing n. These finding agree with those of Wiącek and Molenda [12] for polydisperse samples with continuous PSDs and the results of Wiącek et al. [19] for binary granular packings. The results suggested that the distribution of contact angles in polydisperse granular packings was determined by number of particle size classes and the authors suggested the existence of a certain value of n above which the anisotropy of contact normal orientations decreases with increasing g. In this study, the degree of anisotropy in the distribution of contact angles decreased throughout the entire range of n; however, the change in a value with number of particle size classes occurred more slowly for \(n > 5\).

4 Conclusions

In this study, uniaxial confined compression tests were simulated for polydisperse sphere packings with uniform PSDs using DEM. Mixtures with equal number fractions of particles with different sizes were generated to determine the threshold number of particle size fractions above which the structural properties and geometric anisotropy of the mixtures remained constant. The effect of the degree of heterogeneity in particle size on the critical value of n was investigated for packings with various particle size ratios.

The packing density and average coordination number both decreased with increasing number of particle size fractions from two to five in mixtures with \(g \le 1.67\). In mixtures with \(g > 1.67\), the packing density and average coordination number increased with increasing n from two to three. These results indicate that the threshold value of n above which structural properties (i.e., packing density and coordination number) remain constant was affected by g; however, for g values ranging from 1.25 to 5, the critical value was \(n=5\).

The findings of these study revealed the strong relation between geometric anisotropy and number of particle size fractions in the studied mixtures. Regardless of g, the geometric anisotropy of the distribution of contact normal orientation decreased with increasing n.

Till date, few efforts have investigated the properties of granular mixtures with discrete PSDs and uniform number fractions of particles. Thus, this study provides valuable information about the structural properties of granular packings with equal number fractions of particles with different sizes.

References

Zhang, Y.M., Napier-Munn, T.J.: Effects of particle size distribution, surface area and chemical composition on Portland cement strength. Powder Technol. 83, 245–252 (1995)

Bentham, C., Dutt, M., Hancock, B., Elliott, J.: Effects of size polydispersity on pharmaceutical particle packings. In: Garcia-Rojo, R., Herrmann, H.J., McNamara, S. (eds.) Powders and Grains 2005. Balkema, Rotterdam (2005)

Voivret, C., Radjaï, F., Delenne, J.-Y., El Youssoufi, M.S.: Multiscale force networks in highly polydisperse granular media. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 178001 (2009)

Remy, B., Khinast, J.G., Glasser, B.J.: Polydisperse granular flows in a bladed mixer: experiments and simulations of cohesionless spheres. Chem. Eng. Sci. 66, 1811–1824 (2011)

Figura, L.O., Teixeira, A.A.: Food Physics: Physical Properties-Measurement and Applications. Springer, Berlin (2007)

McGeary, R.K.: Mechanical packing of spherical particles. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 44, 513–523 (1961)

Hwang, K.J., Wu, Y.S., Lu, W.M.: Effect of size distribution of spheroidal particles on the surface structure of a filter cake. Powder Technol. 91, 105–113 (1997)

Rassolusly, S.M.K.: The packing density of ‘perfect’ binary mixtures. Powder Technol. 103, 145–150 (1999)

Voivret, C., Radjaï, F., Delenne, J.-Y., El Youssoufi, M.S.: Space-filling properties of polydisperse granular media. Phys. Rev. E 76 (2007). Art. No. 021301

Göncü, F., Durán, O., Luding, S.: Constitutive relations for the isotropic deformation of frictionless packings of polydisperse spheres. C. R. Mec. 338, 570–586 (2010)

Wiącek, J., Molenda, M.: Microstructure and micromechanics of polydisperse granular materials: effect of the shape of particle size distribution. Powder Technol. 268, 237–343 (2014)

Wiącek, J., Molenda, M.: Effect of particle polydispersity on micromechanical properties and energy dissipation of granular mixtures. Particuology 16, 91–99 (2014)

Wiącek, J.: Geometrical parameters of binary granular mixtures with size ratio and volume fraction: experiments and DEM simulations. Granul. Matter 18, 42 (2016)

Wiącek, J., Molenda, M., Stasiak, M.: On the effect of number of granulometric fractions on structure and micromechanics of compresses granular packings. Particuology (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.partic.2018.01.001

Lade, P.V., Liggio, C.D., Yamamuro, J.A.: Effects of non-plastic fines on minimum and maximum void ratios of sand. Geotech. Test. J. GTJODJ 21, 336–347 (1998)

Shire, T., O’Sullivan, C., Hanley, K.: The influence of finer fraction and size-ratio on the micro-scale properties of dense bimodal materials. In: Soga, K., Kumar, K., Biscontin, G., Kuo, M. (eds.) Geomechanics from Micro to Macro. Taylor & Francis Group, London (2015)

Jalali, P., Li, M.: Model for estimation of critical packing density in polydisperse hard-disc packings. Phys. A 381, 230–238 (2007)

Sánchez, J., Auvient, G., Cambou, B.Ł.: Coordination number and geometric anisotropy in binary sphere mixtures. In: Soga, K., Kumar, K., Biscontin, G., Kuo, M. (eds.) Geomechanics from Micro to Macro. Taylor & Francis Group, London (2015)

Wiącek, J., Parafiniuk, P., Stasiak, M.: Effect of particle size ratio and contribution of particle size fractions on micromechanics of uniaxially compressed binary sphere mixtures. Granul. Matter 19, 34 (2017)

Roozbahani, M.-M., Huat, B.-B.-K., Asadi, A.: The effect of different random number distributions on the porosity of spherical particles. Adv. Powder Technol. 24, 26–35 (2013)

Skrinjar, O., Larsson, P.-L.: On discrete element modelling of compaction of powders with size ratio. Comput. Mater. Sci. 31, 131–146 (2004)

Chen, D., Torquato, S.: Confined disordered strictly jammed binary sphere packings. Phys. Rev. E 92, 062207 (2015)

Furnas, C.C.: Grading aggregates I—mathematical relations for beds of broken solids of maximum density. Ind. Eng. Chem. 23, 1052–1058 (1931)

Zou, R.P., Bian, X., Pinson, D., Yang, R.Y., Yu, A.B., Zulli, P.: Coordination number of ternary mixtures of spheres. Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 20, 335–341 (2003)

O’Sullivan, C., Cui, L.: Micromechanics of granular material response during load reversals: combined DEM and experimental study. Powder Technol. 193, 289–302 (2009)

Yi, L.Y., Dong, K., Zou, R., Yu, A.: Coordination number of the packing of ternary mixtures of spheres: DEM simulations versus measurements. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 50, 8773–8785 (2011)

Ogarko, V., Luding, S.: Prediction of polydisperse hard-sphere mixture behavior using tridisperse systems. Soft Matter 9, 9530–9534 (2013)

Cundall, P.A., Strack, O.D.: A discrete element model for granular assemblies. Géotechnique 29, 47–65 (1979)

EDEM Software. Retrieved from www.dem-solutions.com/ software/edem-software. Accessed 01 May 2017 (2018)

Dutt, M., Elliott, A.E.: Granular dynamics simulations of the effect of grain size dispersity on uniaxially compacted powder blends. Granul. Matter 16, 243–248 (2014)

Krishna P., Pandey D.: Close-packed structures. In: Taylor, C.A., (ed.) International Union of Crystallography Commission on Crystallographic Teaching, First Series Pamphlets, No. 5, University College Cardiff Press, Cardiff. (1981)

Wiącek, J., Molenda, M.: Representative elementary volume analysis of polydisperse granular packings using discrete element method. Particuology 27, 88–94 (2016)

Eurocode 1, “Actions on Structures. Part 4. Silos and Tanks”, EN 1991–4 (2006)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wiącek, J., Stasiak, M. Effect of the particle size ratio on the structural properties of granular mixtures with discrete particle size distribution. Granular Matter 20, 31 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10035-018-0800-7

Received:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10035-018-0800-7