Abstract

Mental illness heightens risk of medical emergencies, emergency hospitalisation, and readmissions. Innovations for integrated medical–psychiatric care within paediatric emergency settings may help adolescents with acute mental disorders to get well quicker and stay well enough to remain out of hospital. We assessed models of integrated acute care for adolescents experiencing medical emergencies related to mental illness (MHR). We conducted a systematic review by searching MEDLINE, PsychINFO, Embase, and Web of Science for quantitative studies within paediatric emergency medicine, internationally. We included populations aged 8–25 years. Our outcomes were length of hospital stay (LOS), emergency hospital admissions, and rehospitalisation. Limits were imposed on dates: 1990 to June 2021. We present a narrative synthesis. This study is registered on PROSPERO: 254,359. 1667 studies were screened, 22 met eligibility, comprising 39,346 patients. Emergency triage innovations reduced admissions between 4 and 16%, including multidisciplinary staffing and training for psychiatric assessment (F(3,42) = 4.6, P < 0.05, N = 682), and telepsychiatry consultations (aOR = 0.41, 95% CI 0.28–0.58; P < 0.001, N = 597). Psychological therapies delivered in emergency departments reduced admissions 8–40%, including psychoeducation (aOR = 0.35, 95% CI 0.17–0.71, P < 0.01, N = 212), risk-reduction counselling for suicide prevention (OR = 2.78, 95% CI 0.55–14.10, N = 348), and telephone follow-up (OR = 0.45, 95% CI 0.33–0.60, P < 0.001, N = 980). Innovations on acute wards reduced readmissions, including guided meal supervision for eating disorders (P = 0.27), therapeutic skills for anxiety disorders, and a dedicated psychiatric crisis unit (22.2 vs 8.5% (P = 0.008). Integrated pathway innovations reduced readmissions between 8 and 37% including family-based therapy (FBT) for eating disorders (X2(1,326) = 8.40, P = 0.004, N = 326), and risk-targeted telephone follow-up or outpatients for all mental disorders (29.5 vs. 5%, P = 0.03, N = 1316). Studies occurred in the USA, Canada, or Australia. Integrated care pathways to psychiatric consultations, psychological therapies, and multidisciplinary follow-up within emergency paediatric services prevented lengthy and repeat hospitalisation for MHR emergencies. Only six of 22 studies adjusted for illness severity and clinical history between before- and after-intervention cohorts and only one reported socio-demographic intervention effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mental disorders are experienced by 10% of children and adolescents globally [1], and 16% in the UK [2]. Physical health emergencies often have mental health-related (MHR) aetiologies, exacerbators, and consequences, indicating that mental and physical illnesses are interrelated [3]. Comorbid mental disorders are present in 10–19% of all paediatric emergencies [4, 5], and mental illness significantly increases risk of medical emergency admission and readmissions [6]. Frequent attenders at paediatric emergency departments more commonly present with psychiatric complaints than with accidental injury [7]. Examples of physical manifestations of mental disorders are self-harm and suicide attempts, psychological trauma leading to somatisation, eating disorders leading to serious nutritional deficiencies, and substance and alcohol dependence leading to intoxication [5]. This exemplifies how some MHR emergencies are inherently multimorbid and require integrated paediatric and psychiatric care. Fifty percent of all lifetime mental disorders have an onset prior to 14 years of age [8], and mental illness hinders social, educational, and occupational development. [9] Thus, there is a need to intervene effectively at the critical moment when adolescents present with MHR emergencies, to prevent persistent and pervasive complications [10].

MHR emergencies require a multidisciplinary response to comprehensively meet the biopsychosocial needs of young people. National and local health policies in the UK advocate for integrated care, through collaborations between providers, intervening early, and evidence-based mental health services [11,12,13]. At a regional level, introducing multidisciplinary teams and cross-service planning reduced the average length of inpatient stay 22% and admissions 7% [14]. Whilst local targets for integrated emergency care for children and adolescents were established in 2019, challenges in collaborative commissioning persist. This informed our research objective to evidence effective models of care to encourage investment.

Mental illness is often lifelong [15], and 8–13% of those hospitalised in paediatric settings return within one month, significantly higher than non-MHR admissions [4, 16]. The effectiveness of therapeutic modalities on improving health outcomes is well documented. [17] For example, integrating family-based therapy within acute hospitalisation has been provided in medical emergencies that are accompanied by a comorbid mental illness—particularly eating disorders and suicide attempts. This is known as partial hospitalisation, which involves transferring the patient from an inpatient ward to outpatient family-based therapy once medical stabilisation is complete; aimed at reducing the degree of institutionalisation [18]. Integrated family-based therapy as partial hospitalisation improved young people’s psychosocial functioning and parental self-efficacy to support the young person to stay well. This review adopted the hypothesis that providing family-based therapy as an integrated intervention from acute hospitalisation for MHR emergencies would reduce repeat hospitalisation, helping young people to stay out of hospital. Other types of integrated psychological interventions are aimed at supporting young people to stay out of hospital after an MHR emergency, such as outpatient follow-up with a psychiatrist, or individual therapy, which were also included in this review. We know that these interventions are health effective, but we do not yet know whether they are effective for health maintenance. Preferably, evaluations will test for sustained health outcomes, but patient data is often not recorded centrally after leaving the hospital. This highlights the need to monitor admissions, readmissions, and length of hospital stay (LOS), as proxies for efficient and sustained recovery, with minimal institutionalisation. Recent evidence indicates that integrating multidisciplinary staffing to provide both medical and psychiatric triage, as well as delivering low-intensity psychological therapy within acute psychiatric settings improved service efficiency and treatment capacity [19]. Yet, there is limited evidence whether these therapies improve healthcare efficiency when integrated into paediatric emergency settings.

Innovations for integrated care implies that the individual received both medical and psychological emergency care in one care-package, i.e. initiated within one emergency care visit. This optimises patients’ time rather than visiting multiple providers for different aspects of care. When facilities do not allow integrated care provision in one location, it may be necessary to supplement care with additional specialist services. Thus, the term ‘innovation’ refers to establishing models of integrated care that are delivered by, or integrated alongside, emergency departments and acute hospitalisation. One example of integrated care is providing psychological assessment and treatment, subject to the patient being well enough to participate, alongside acute medical care [20]—instead of prolonged hours of unstructured time and social isolation on an acute ward. These innovations have implications not only for improving health outcomes [11, 17], but most importantly to avoid institutionalisation by minimising time spent in hospital and supporting return to a home environment [17].

We identified an evidence gap—whether embedding psychiatry within paediatric emergency settings improves health maintenance to stay out of hospital. We present an evidence synthesis and implications for clinical practice and research.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

This systematic review adhered to PRISMA guidelines [21]. We included quantitative observational studies published in peer-reviewed journals that evaluated innovations located within acute paediatric hospital services, such as the emergency department, emergency admission wards, emergency crisis centres, intensive care wards, and emergency referrals from these acute services to outpatient services. We included both innovations for integrated care provision and integrated care pathways, whenever the care was delivered as emergency healthcare. This included any intervention that provided psychological care provided by mental health practitioners, such as family-based therapy, psychiatric follow-up or aftercare, or individual therapy, either within, or integrated alongside, emergency healthcare. Given that intensive therapeutic interventions delivered alongside acute hospitalisation are conceptually different from brief psychological support delivered in emergency departments and inpatient wards, we also extracted the staffing requirements and intervention duration for all studies reviewed—important considerations for cost–benefit analysis. We included study samples up to 25 years of age [22] if the study also included those aged below 18 years. The outcomes of interest were emergency admissions, emergency rehospitalisation, and LOS in acute settings. All study designs using a control group were included.

We defined participants as presenting with MHR emergencies, which are identified symptomatically and behaviourally, considering that underlying mental illnesses are not necessarily diagnosed. Hence, we included cohorts of either MHR emergency presentations (i.e, self-harm, suicide attempts, and intoxication) as well as specific mental illnesses (i.e. eating disorders, substance abuse and alcohol-related disorders, mood disorders, neurodevelopmental disorders, and psychotic disorders). These groups were informed by the ICD-11 and a service evaluation for MHR paediatric emergencies [5].

The search strategy was developed in correspondence with a university librarian. We searched MEDLINE (May 28, 2021), PsycINFO (Jun 10, 2021), Embase (Jun 10, 2021), and Web of Science (Jun 15, 2021) for published articles. We searched database subject headings and free-text keywords using a four-concept strategy consisting of (i) young people aged < 26 years, (ii) acute hospital settings (i.e. acute paediatrics, emergency medicine, and emergency department), (iii) with symptoms indicating mental illness, and (iv) admissions, LOS, or readmissions. We iteratively updated the search as new terms were identified in key texts found from the search. We imposed a date restriction from the year 1990 to current. Search strategies are provided in supplementary file 1.

Search results were de-duplicated in Zotero and again in Covidence software for systematic reviews. Two reviewers (MO and MA) identified studies that met inclusion criteria through screening of all titles and abstracts, then full-text screening using Covidence. Any discrepancies were resolved through consensus after discussion between both reviewers.

Data extraction and quality assessment

A Microsoft Excel sheet was used to extract study designs, country, dates, sample sizes, participant characteristics (including gender, age, ethnicity, and diagnoses), innovation and comparator characteristics, and outcome measures (numeric and risk ratios). Two reviewers (MO and MA) blindly assessed the quality of extracted studies using an adapted version of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for observational designs [23]. The NOS item measuring absence of outcome at the start of the study was removed given it was not relevant to our extracted studies, which all used retrospective data. We added two questions to the ‘comparability’ section of the NOS, adopted from questions 10 and 11 of the National Heart, Lung and Blood institute’s (NHLBI) ‘Quality assessment tool for before–after studies with no control group’ [24], assessing the appropriate time frame of outcome measurement to capture intervention effects and statistical comparisons. Quality assessment scores had an 85% interrater reliability. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion to agree to a final score. Quality assessment scores are provided in supplementary table 2.

All 22 studies used retrospective designs with routinely collected hospital data, comprising 16 before–after intervention designs, three non-randomised control trials, and three retrospective observational designs. Thus, all samples were complete in representing the population of young people using those services. Six studies were rated as good quality [25,26,27,28,29,30], 12 were fair quality [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42], and 4 were poor quality [43,44,45,46]. There was considerable variability between study methodologies, particularly the post-intervention time frame to capture the intervention effects. The main area of weakness was the comparability of intervention and control groups, whereby four studies provided no statistical calculation, only six controlled for potential confounders, and only three used a rigorous method such as propensity score matching or interrupted time series analysis [25, 27, 38]. All studies were included in the narrative synthesis.

Data analysis

We grouped studies by emergency care setting and innovation type to investigate the effect of healthcare innovations in each setting. A narrative synthesis was conducted for (i) triage in the emergency department, (ii) psychological therapy in the emergency department, and (iii) psychological therapy on the inpatient ward or provided as an integrated pathway referral. The narrative synthesis followed guidance for systematic reviews [47] to critique the evidence for effectiveness of interventions—i.e. what interventions (mechanisms) were effective (outcomes) for whom, in what settings and locations (contexts). This also identified evidence gaps. Due to heterogeneity in intervention types in the final set of studies, a meta-analysis was not considered.

Results

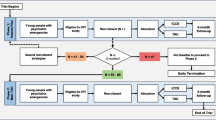

Our initial search generated 2033 results, of which 366 were duplicates, resulting in 1667 studies to be screened. After title and abstract screening, 50 relevant articles were identified, of which 22 met inclusion criteria after full-text screening. No further studies were identified through forward and backward searches in the references. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flowchart of study selection.

All studies were from high-income countries, with 15 in the United States of America (USA), six in Canada, and one in Australia. Six studies included participants over the age of 18 years. In total, 39,346 young people were included across all studies, of whom between 6 and 37% were admitted for emergency care, spending between 183 and 363 min in the emergency department. All participants were referred by the emergency department for assessment by a mental health practitioner. Measuring readmission after discharge ranged between 30 days and one year across all studies, resulting in a wide-ranging 16–71% of participants with emergency readmissions. All studies extracted clinical characteristics from patient records, recorded as ICD-9 or -10 codes [48], referral for psychiatric assessment or service, or surveyed caregivers on the presence of intentional self-injury. Most studies reported patient demographics, but only one stratified intervention effects by age. For outcomes, ten studies reported on emergency admissions, six reported LOS in the emergency department, six on LOS in inpatient setting, and six on inpatient readmissions after discharge. Factors significantly associated with emergency admissions in multivariate analyses were (i) at the service level, higher volume of emergency visits (incident rate ratio, IRR = 1.004, 95% CI 1.003–1.005), and proportion of MHR emergencies (IRR = 1.004, 95% CI 1.002–1.006) [27]; (ii) at the individual level, older age (OR = 1.17, 95% CI 1.03–1.33), suicidal ideation with or without self-harm (OR = 3.07 or 4.70, 95% CI 1.12–11.01), and clinical diagnoses (when compared to depression), including bipolar or other mood disorders (OR = 13.05, 95% CI 3.57–47.71), and oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder (OR = 3.88, 95% CI 1.11–13.58) [30].

The first set of innovations improved psychiatric triage in the emergency department, including telepsychiatry consultations (N = 2), multidisciplinary staffing (N = 3), and clinical guidance training (N = 1), which were effective in reducing LOS [27, 34, 37, 39] and emergency admissions (see Table 1) [26, 34, 38]. Innovations for staff restructuring formed a multidisciplinary team comprising child psychiatrists and mental health social workers, supplemented with staff training in psychiatric triage, which reduced admissions 4–16% and LOS by 85–150 min (P < 0.05). [27, 34] Multidisciplinary staffing for medical and psychiatric assessments supported a new referral pathway to an urgent care team, which reduced admissions from the emergency department from 6.3 to 2.3% (F(3,42) = 4.6, P < 0.05) [38]. Next, the use of telepsychiatry consultations in the emergency department reduced emergency admissions (OR = 0.42, 95% CI = 0.30–0.59, P < 0.01); which was sustained after accounting for small differences in age and diagnoses between pre- and post-intervention cohorts (adjusted OR = 0.41, 95% CI 0.28–0.58, P < 0.01) [26]. Yet, whilst admissions reduced, there was longer LOS in the emergency department by 1 h (183 vs 125 min, P < 0.01), arguably, a fair trade-off to avoid admission. However, this longer LOS may have been confounded by differences in staff and patient characteristics during the day shift (the intervention group) and the night shift (the control group who received face-to-face consultations), which were not accounted for. A counterargument is provided by another telepsychiatry consultation study, which used a rigorous study design of 3 months before–after intervention, reporting a reduction in LOS from 285 to 193 min (P = 0.03) [39]. Alternatively, introducing clinical guidance training without staff restructuring or telepsychiatry reduced LOS from 259 to 216 min (P = 0.01) [37], though admission rates were not studied.

Next, innovations embedding psychological therapies within the emergency department (see Table 2), included psychoeducation (N = 3), a newly established crisis unit (N = 3), and telephone follow-up (N = 2). Suicide prevention psychoeducation was delivered to caregivers of adolescents with suicidal ideation in a mixed gender and white/non-white cohort; whilst the innovation did not significantly reduce return emergency visits, there was a significant reduction in emergency admissions (32.8% pre-intervention to 24.5% post-intervention) (OR = 2.78, 95% CI 0.55–14.10, N = 185, P < 0.01) [29]. This reduction did not differ by ethnicity, age, gender, insurance type, or clinical complexity. When targeting all MHR emergencies, a psychiatric liaison program delivered by a social worker and a child psychiatrist similarly reduced emergency admissions (adjusted OR = 0.35, 95% CI 0.17–0.71, P < 0.01), and LOS 27% (95% CI 0–46%, P = 0.05) [30]. A 24-h triage and psychoeducation service reduced LOS from 332 to 244 min (P < 0.01) [41], but reported no change in admissions.

The most effective innovation in the emergency department was introducing a psychiatric crisis unit, which significantly reduced admissions between 15 and 20% [33, 46] and LOS around 45% [40, 46]. A large tertiary care hospital established an inpatient psychiatric urgent care unit adjacent to the emergency department, which reduced the rate of inpatient admissions to the paediatric acute ward from 22.2 to 8.5%, 12 months pre- and post-intervention (P = 0.008) [33]. This intervention increased the capacity for psychiatric assessments (226 vs 91, P < 0.01), yet the LOS increased by 55 min to deliver psychological therapies. There was a 40% reduction in admissions and 45% reduction in LOS after a complex intervention encompassing a psychiatric crisis unit, multidisciplinary and structured triage, and separate waiting rooms for high-acuity and low-acuity patients, though no raw data were reported. [46].

Introducing a multidisciplinary telephone follow-up service from the emergency department for patients and caregivers of MHR emergencies, consisting mainly of suicide-related emergencies, reduced admissions by 16% (OR = 0.45, 95% CI 0.33–0.60, P < 0.001) [28]. For LOS, another telephone follow-up study reported a monthly total LOS reduction from 315 to 298 h [43]. All psychological innovations required psychiatric staff for assessment and treatment.

Innovations embedding psychological therapies within acute inpatient settings included therapeutic skills training (N = 1), meal supervision (N = 1), and outpatient aftercare or telephone follow-up (N = 3), which reduced readmissions between 7.7 and 37% and inpatient LOS between 3 and 31 days (see Table 3). Inpatient innovations included a therapeutic skills group for anxiety disorders, encompassing grounding exercises, meditation, yoga, and relaxation strategies [44], which reduced 30-day readmissions (9.5%) and 90-day readmissions (15.6%) compared to individual and family psychoeducation; 74% (N = 64) were female and no statistical comparison was reported. A standardised meal supervision program for eating disorders (N = 56), compared to no supervision in the control group (N = 52), comprised a trained staff member at the bedside discussing patient-specific preferences, averting conversations about weight, body image, and calories [36]. Playing music or watching TV acted as distractive coping strategies. The innovation reduced LOS by 3 days (P = 0.27) reaching weight restoration in shorter time. Participants were predominantly from White ethnicities (89–100%) and female (82–87%).

For integrated pathways, introducing family-based therapy (FBT) to an existing partial hospitalisation program (PHP) for eating disorders reduced 3-year readmissions by 7.7% [35]. The FBT innovation used family-based psychotherapy and art therapy (N = 138), compared to traditional PHP, involving relapse prevention, goal setting, and neurobiology psychoeducation, which significantly reduced readmission (X2 (1,326) = 8.40, P = 0.004, N = 188). Two further studies evaluated outpatient FBT, specifically for individuals with anorexia nervosa. Family-based psychotherapy compared to a control group of psychoeducational family sessions [32] significantly reduced readmissions for weight restoration (34.4 vs. 71.4%, P = 0.03). In the second study, both intervention (N = 32) and control (N = 16) groups received 20 FBT sessions, yet the intervention group received an additional 20 FBT psychotherapy sessions, whereas controls received individual cognitive-based therapy (CBT) [42]. The prolonged FBT group had significantly higher 12-month readmissions (28.2 vs. 14.3%, P < 0.001), albeit shorter readmission LOS (mean days = 71.93, SD = 68.28) than the controls (mean days = 12.51, SD = 24.67, P < 0.001). Thus, FBT treatment modality and length of therapy mattered. In both studies, participants were predominantly female (94–95%), and commonly had comorbidity (21.7% mood disorders, 19.6% anxiety disorders) [42] and eating disorder psychopathology. [32]

Two Canadian studies compared those who received outpatient aftercare comprising any follow-up assessment, onward referral, residential treatment, or physician service, compared to those who received no aftercare, and reported contrasting findings. One recorded a 32% reduction in 90-day readmissions (adjusted hazard ratio, aHR = 0.68, 95% CI 0.58–0.80, P < 0.001, N = 15,628) [31]; the other a 38% increase in risk of 1-year readmission (aHR = 1.38, 95% CI 1.14–1.66, P < 0.001, N = 3004) [25]. However, these contrasting findings might explain more about short- and long-term readmission in this cohort rather than the intervention effects of general outpatient follow-up, given that the 'no aftercare' groups were allocated based on lower clinical acuity, thus, causing allocation bias. Alternatively, an integrated intervention for ‘troubleshoot’ telephone follow-up service was provided for caregivers (N = 1211) [45]. The modal recipient groups were those with depressive, attention deficit hyperactivity (ADHD), anxiety, post-traumatic stress (PTSD), and autism spectrum disorders due to high risk of readmission. This reduced 30-day readmission by 29.5% in year 1, 7.9% in year 2, and 5.1% in year 3.

This review summarises evidence for healthcare innovations within three paediatric emergency settings. First, within emergency departments: multidisciplinary and telepsychiatry triage both reduced LOS in the emergency department and emergency admissions; however, telepsychiatry showed propensity to increase time spent in the emergency department. Early intervention therapy in the emergency department, either through short-term psychoeducation, telephone follow-up, or a dedicated psychiatric unit for high-acuity patients reduced admissions between 10 and 35%, which simultaneously reduced waiting times. Second, on the acute ward, psychological therapy for anxiety disorders and guided meal supervision for eating disorders showed promise for reducing LOS and readmissions; yet robust methods were lacking. Third, integrated interventions alongside hospitalisation signposted adolescents with eating disorders to FBT delivered as partial hospitalisation, which reduced readmissions by 9–37%. However, prolonging FBT up to 40 sessions compared to 20 sessions increased readmissions by 14%. This evidence suggests that engaging caregivers of adolescents with MHR crises in psychological intervention helped adolescents to avoid institutionalisation within medical hospitals.

Discussion

This is the first evidence synthesis for healthcare innovations of integrated care for young people with MHR emergencies to reduce emergency hospitalisation and rehospitalisation, and length of hospital stay—that is, to get well quickly and stay well enough to remain out of hospital. These models of integrated care focussed on embedding psychiatric consultations to improve triage into acute hospitalisation and embedding psychological therapies into typically medical services to improve integrated pathways within inpatient services. Innovations for integrated care and integrated pathways set out to improve the comprehensiveness of care for medical emergencies with aetiology in mental disorder [3], such as self-inflicted harm, eating disorders, and intoxication. Innovations for integrated care show promising evidence for reducing the rate of emergency admissions to an acute ward, the LOS in both the emergency department and inpatient setting, and the rehospitalisation rate after discharge. Thus, integrated care not only improves health outcomes [17, 18] and effectively reduces psychiatric hospitalisation [19]—this review adds that signposting to psychological interventions also reduces emergency readmissions in paediatric emergency settings too. Whilst there is sometimes no alternative to hospitalisation for medical emergencies [16, 17], integrating psychiatric care into emergency services helps to triage effectively, intervene earlier, and signpost to therapeutic support, reducing lengthy and repeat hospitalisation.

Engaging family members or guardians was an innovative treatment modality for specific MHR emergencies. This was evident in innovations providing FBT aftercare for eating disorders [32, 35], risk-prevention psychoeducation for guardians of individuals with suicide-related emergencies [29], and risk-targeted follow-up for caregivers of individuals with suicidality, PTSD, ADHD, or autism [28, 45]. The important role of parental figures in aftercare therapies and recovery might be associated with their related risk factors, which are commonly deprivations such as parental mental illness, childhood trauma (ACEs), conflict in the home, and socioeconomic deprivation [49].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, there were more medical emergencies for eating disorders, but fewer for suicidality and substance-related disorders [5], which might be due to increased time spent at home and the absence of school and community activities, respectively. Designing and testing psychological interventions for integrated care should consider differing response styles between clinical cohorts, as well as adjust for annual fluctuations in emergency service utilisation during the COVID-19 pandemic, using multilevel or stratified intervention effects.

Our review identified evidence gaps for what innovations are effective for whom, and in what settings. For instance, family-based therapy delivered as aftercare from acute settings (i.e. partial hospitalisation) for adolescents with eating disorders consistently reduced ‘the revolving door’ of repeat admissions. Yet, robust evidence of psychoeducation for acute inpatients with anxiety-related and eating disorders was limited. Few studies reported ethnicity characteristics of the sample, nor tested intervention effects for individual differences such as ethnicity and gender. Most studies were in predominantly White female populations; thus, socio-demographic differences in responses to treatment modalities are not yet known. This further evidenced the White centricity within mental health research, particularly in paediatrics [50]. Given that all studies involved naturalistic hospital data, this lack of nuance may be due to ethnic disparities in access to psychiatric services [51].

Methodologically, before–after intervention comparisons of hospital data were the typical study design, which sought to mimic a randomised control trial given the homogeneity of setting and participants in the intervention and control groups. However, annual changes in service use [5] demonstrates the need to adjust for individual differences between the pre- and post-intervention cohorts, which was often missing in studies reviewed. Propensity score matching is a robust approach to adjust for these variations, being careful of allocation bias. Better still, future designs should report intervention effects by gender, ethnicity, and clinical cohorts, to evidence what works for whom, and to what effect.

To encourage commissioning, future evaluations must report the resources required for establishing integrated care and pathways, to permit accurate cost–benefit analyses for reducing hospitalisation. All studies we reviewed required multidisciplinary staffing at minimum, and new capital facilities at most. The co-location of psychiatry space as well as expertise, alongside acuity risk triage were key components of reducing over-medicalisation of MHR emergencies and improving access to psychotherapies. Most studies we reviewed were conducted in the USA or Canada. This might be due to country characteristics using private and social insurance as dominant health expenditures [52]. Competitive markets incentivise care providers to be cost-effective. As the UK further implements decentralised commissioning [12], we might see more evaluative research of this kind. However, comprehensive and integrated care is not synonymous with competitive markets [53], and it will be important to keep patient safety, care integration, and quality of care as the rationale for improving efficiency—synonymous with increasing service capacity [13].

Data availability

MO had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All data collected for this article, including data extraction tables, are included in this published article in the tables and supplementary files.

Abbreviations

- ACE:

-

Adverse childhood events

- ADHD:

-

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- aHR:

-

Adjusted hazard ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CBT:

-

Cognitive behavioural therapy

- FBT:

-

Family-based therapy

- ICD-10:

-

International Classification of Diseases version 10

- IRR:

-

Incidence rate ratio

- LOS:

-

Length of stay

- MDT:

-

Multidisciplinary teams

- MHR:

-

Mental health related

- NHLBI:

-

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute

- NOS:

-

Newcastle–Ottawa Scale

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PTSD:

-

Post-traumatic stress disorder

- PHP:

-

Partial hospitalisation program

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- USA:

-

United States of America

References

WHO. Adolescent mental health. [Cited 2021 Sep 17]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health

NHS Digital. Mental Health of Children and Young People in England, 2020: Wave 1 follow up to the 2017 survey. [Cited 2021 Dec 6]. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-in-england/2020-wave-1-follow-up

Aarons G, Monn A, Leslie L et al (2008) The association of mental and physical health problems in high-risk adolescents: a longitudinal study. J Adolesc Health 43:260–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.01.013

Feng J, Toomey S, Zaslavsky A, Nakamura M, Schuster M (2017) Readmission after pediatric mental health admissions. Pediatrics 140:e20171571. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-1571

Chadi N, Piano CS-D, Osmanlliu E, Gravel J, Drouin O (2021) Mental health-related emergency department visits in adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multicentric retrospective study. J Adolesc Health 69:847–850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.07.036

Ronaldson A, Elton L, Jayakumar S, Jieman A, Halvorsrud K, Bhui K (2020) Severe mental illness and health service utilisation for nonpsychiatric medical disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 17:e1003284. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003284

Greenfield G, Okoli O, Quezada-Yamamoto H et al (2021) Characteristics of frequently attending children in hospital emergency departments: a systematic review. BMJ Open 11:e051409. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051409

Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt T, Harrington H, Milne B, Poulton R (2003) Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60:709–717. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.709

Education Policy Institute. Children and Young People’s Mental Health: State of the Nation - The Education Policy Institute. [Cited 2021 Dec 6]. Available from: https://epi.org.uk/publications-and-research/children-young-peoples-mental-health-state-nation/

Steinglass J, Walsh B (2016) Neurobiological model of the persistence of anorexia nervosa. J Eat Disord 4:19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-016-0106-2

Yonek J, Lee C-M, Harrison A, Mangurian C, Tolou-Shams M (2020) Key components of effective pediatric integrated mental health care models: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr 174:487–498. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0023

North West London Clinical Commissioning Groups. NW London sustainability and transformation plan. V01 Oct 2016, pp. 1–61. [Cited 2021 Dec 6]. Available from: https://www.nwlondonccgs.nhs.uk/application/files/8815/8402/7829/nwl_stp_october_submission_v01pub.pdf.

NHS England. NHS mental health implementation plan 2019/20 – 2023/24. [Cited 2021 Dec 6]. Available from: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/nhs-mental-health-implementation-plan-2019-20-2023-24.pdf

West London Mental Health NHS Trust. North West London CAMHS New Model of Care. [Cited 2021 Dec 6]. Available from: https://www.healthcareconferencesuk.co.uk/assets/presentations-post-conference/september-2019/camhs-7-oct/dr-elizabeth-fellow-smith.pdf

Chen H, Cohen P, Kasen S, Johnson JG, Berenson K, Gordon K (2006) Impact of adolescent mental disorders and physical illnesses on quality of life 17 years later. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 160:93–99. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.160.1.93

Edgcomb J, Sorter M, Lorberg B, Zima B (2020) Psychiatric readmission of children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatr Serv 71:269–279. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201900234

Clisu D, Layther I, Dover D et al (2021) Alternatives to mental health admissions for children and adolescents experiencing mental health crises: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591045211044743

Hoste RR (2015) Incorporating family-based therapy principles into a partial hospitalization programme for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: challenges and considerations. J Fam Ther 37:41–60

Chen A, Dinyarian C, Inglis F, Chiasson C, Cleverley K (2020) Discharge interventions from inpatient child and adolescent mental health care: a scoping review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01634-0

Vusio F, Thompson A, Birchwood M, Clarke L (2020) Experiences and satisfaction of children, young people and their parents with alternative mental health models to inpatient settings: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 29:1621–1633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01420-7

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 339:b2700. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2700

Fusar-Poli P (2019) Integrated mental health services for the developmental period (0–25 years): a critical review of the evidence. Front Psychiatry 10:1–17. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00355

Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. 2021. [cited 2021 Jun 18]. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

NHLBI. Study Quality Assessment Tools. 2021. [cited 2021 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

Carlisle C, Mamdani M, Schachar R, To T (2012) Aftercare, emergency department visits, and readmission in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 51:283-293.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2011.12.003

Desai P, Vega R, Adewale A, Manuel M, Shah K, Nianiaris N (2019) The use of telemedicine for child psychiatric consultations in an inner-city hospital. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.144.2MA5.432

Ishikawa T, Chin B, Meckler G, Hay C, Doan Q (2021) Reducing length of stay and return visits for emergency department pediatric mental health presentations. CJEM 23:103–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43678-020-00005-7

Greenfield B, Hechtman L, Tremblay C (1995) Short-term efficacy of interventions by a youth crisis team. Can J Psychiatry 40:320–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674379504000607

Parast L, Bardach N, Burkhart Q et al (2018) Development of new quality measures for hospital-based care of suicidal youth. Acad Pediatr 18:248–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.09.017

Sheridan D, Sheridan J, Johnson K et al (2016) The effect of a dedicated psychiatric team to pediatric emergency mental health care. J Emerg Med 50:e121–e128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.10.034

Cheng C, Chan C, Gula C, Parker M (2017) Effects of outpatient aftercare on psychiatric rehospitalization among children and emerging adults in Alberta, Canada. Psychiatr Serv 68:696–703. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201600211

Gusella J, Campbell A, Lalji K (2017) A shift to placing parents in charge: does it improve weight gain in youth with anorexia? Paediatr Child Health 22:269–272. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/pxx063

Hasken C, Wagers B, Sondhi J, Miller J, Kanis J (2020) The impact of a new on-site inpatient psychiatric unit in an urban paediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000002177

Holder S, Rogers K, Peterson E, Shoenleben R, Blackhurst D (2017) The impact of mental health services in a pediatric emergency department: the implications of having trained psychiatric professionals. Pediatr Emerg Care 33:311–314. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000000836

Huryk K, Casasnovas A, Feehan M, Paseka K, Gazzola P, Loeb K (2021) Lower rates of readmission following integration of family-based treatment in a higher level of care. Eat Disord 29:677–684. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2020.1823173

Kells M, Schubert-Bob P, Nagle K et al (2017) Meal supervision during medical hospitalization for eating disorders. Clin Nurs Res 26:525–537. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054773816637598

Mahajan P, Thomas R, Rosenburg D et al (2007) Evaluation of a child guidance model for visits for mental disorders to an inner-city pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 33:212–217. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0b013e31803e177f

Parker K, Roberts N, Williams C, Benjamin M, Cripps L, Woogh C (2003) Urgent adolescent psychiatric consultation: from the accident and emergency department to inpatient adolescent psychiatry. J Adolesc 26:283–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-1971(03)00014-9

Reliford A, Adebanjo B (2019) Use of telepsychiatry in pediatric emergency room to decrease length of stay for psychiatric patients, improve resident on-call burden, and reduce factors related to physician burnout. Telemed J E Health 25:828–832. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2018.0124

Rogers S, Griffin L, Masso P Jr, Stevens M, Mangini L, Smith S (2015) CARES: improving the care and disposition of psychiatric patients in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 31:173–177. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000000378

Uspal N, Rutman L, Kodish I, Moore A, Migita R (2016) Use of a dedicated, non-physician-led mental health team to reduce pediatric emergency department lengths of stay. Acad Emerg Med 23:440–447. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12908

Wallis A, Miskovic-Wheatley J, Madden S, Alford C, Rhodes P, Touyz S (2018) Does continuing family-based treatment for adolescent anorexia nervosa improve outcomes in those not remitted after 20 sessions? Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 23:592–600. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104518775145

Cummings M, Kandefer S, Van Cleve J et al (2020) Preliminary assessment of a novel continuum-of-care model for young people with autism spectrum disorders. Psychiatr Serv 71:1313–1316. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201900574

McDowell G, Valleru J, Adams M, Fristad MA (2020) Centering, affective regulation, and exposure (CARE) group: mindful meditation and movement for youth with anxiety. Evid-Based Pract Child Adolesc Ment Health 5:139–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/23794925.2020.1784058

Ramsbottom H, Farmer L (2018) Reducing pediatric psychiatric hospital readmissions and improving quality care through an innovative readmission risk predictor tool. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs 31:14–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcap.12203

Stricker F, O’Neill K, Merson J, Feuer V (2018) Maintaining safety and improving the care of pediatric behavioral health patients in the emergency department. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 27:427–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2018.03.005

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, Britten N, Roen K, Duffy S (2006) Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme Version. Lancaster University, UK, p b92

WHO. International Classification of Diseases (ICD). [Cited 2021 Dec 6]. Available from: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/classification-of-diseases

Adolescence: Developmental stage and mental health morbidity. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2011; 57: 13–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764010396691

Walker S, Barnett P, Srinivasan R, Abrol E, Johnson S (2021) Clinical and social factors associated with involuntary psychiatric hospitalisation in children and adolescents: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and narrative synthesis. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 5:501–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00089-4

Chui Z, Gazard B, MacCrimmon S et al (2020) Inequalities in referral pathways for young people accessing secondary mental health services in south east London. Eur Child Adolesc Psych 30:113–1128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01603-7

International Health Care System Profiles. [Cited 2021 Dec 6]. Available from: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/international-health-policy-center/system-profiles

The Health Foundation. Competition in healthcare - The Health Foundation. [Cited 2021 Dec 6]. Available from: https://www.health.org.uk/publications/competition-in-healthcare

Funding

Authors MO, SB, and DN are funded by National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration Northwest London. The views expressed in the publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the UK Department of Health and Social Care or its arm's length bodies, or other government departments. The funder had no role in study design, study selection, analysis, interpretation, or writing of the report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DN initiated the study. MO registered the study with PROSPERO. MO and MA conducted the search, screening, and quality assessment. MO and MA extracted the data. All authors interpreted the results. MO drafted the manuscript and is the guarantor. All authors revised the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Otis, M., Barber, S., Amet, M. et al. Models of integrated care for young people experiencing medical emergencies related to mental illness: a realist systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 32, 2439–2452 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-02085-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-02085-5