Abstract

Background

Frequent presenters (FPs) are a group of individuals who visit the hospital emergency department (ED) frequently for urgent care. Many among the group present with the main diagnosis of mental health conditions. This group of individual tend to use ED resources disproportionally and significantly affects overall healthcare outcomes. No previous reviews have examined the profiles of FPs with mental health conditions.

Aims

This study aims to identify the key socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who frequently present to ED with a mental health primary diagnosis by performing a comprehensive systematic review of the existing literature.

Method

PRISMA guideline was used. PubMed, PsycINFO, Scopus and Web of Science (WOS) were searched in May 2023. A manual search on the reference list of included articles was conducted at the same time. Covidence was used to perform extraction and screening, which were completed independently by two authors. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined.

Results

The abstracts of 3341 non-duplicate articles were screened, with 40 full texts assessed for eligibility. 20 studies were included from 2004 to 2022 conducted in 6 countries with a total patient number of 25,688 (52% male, 48% female, mean age 40.7 years old). 27% were unemployed, 20% married, 41% homeless, and 17% had tertiary or above education. 44% had a history of substance abuse or alcohol dependence. The top 3 diagnoses are found to be anxiety disorders (44%), depressive disorders (39%) schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders (33%).

Conclusion

On average, FPs are middle-aged and equally prevalent in both genders. Current data lacks representation for gender-diverse groups. They are significantly associated with high rates of unemployment, homelessness, lower than average education level, and being single. Anxiety disorder, depressive disorder, and schizophrenia spectrum disorders are the most common clinical diagnoses associated with the group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The hospital emergency department (ED) is the first point of contact when people seek urgent medical care. In Australia, there were 8.8 million ED visits in 2021–2022, with a total population of under 26 million [1]. Other than the well-known physical health emergencies like myocardial infarction or stroke, mental health services are provided in the ED as well. Mental health-related presentations accounted for 3.5% of all ED presentations in the Australian public health system in 2020–2021 [2]. A group of individuals commonly known as the ‘frequent presenter’ (FP) repeatedly present themselves to ED seeking emergency care. Many have labelled this group of patients as ‘frequent flyers’ [3]. They are well known for disproportionally occupying the emergency medical resources and contributing to the increasingly overcrowded ED [4, 5]. They place a significant strain on emergency medical resources, and many frontline healthcare workers have struggled to come up with solutions to reduce the number of presentations [6]. On the other hand, people who present to the ED with mental health complaints tend to face longer waiting hours and poorer care compared to those with general medical conditions [7]. We do acknowledge that this is a complicated issue with a wide variety of different presentations or medical complications within the FP group. Currently, there are gaps in knowledge in terms of the community modelling of the issue, public expectations, and attitudes towards different types of mental health services, and the relationship between FPs’ presentation with their social or clinical factors. To address the situation better, policymakers first need to understand the needs of this group of patients and initiate strategies tailored to their social and clinical characteristics. Numerous studies have been published in the past investigating key features of FPs with mental health conditions. This systemic review aims to identify and consolidate the key socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of FPs with a primary mental health diagnosis from existing literature to provide a starting point for future engagement.

2 Method

A comprehensive systematic search and review of published studies on frequent presenters with mental health conditions in hospital ED was conducted based on Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [8].

Search terms were designed to combine both medical subject headings (MeSH) with common terms used for frequent presenters and/or frequent presentations. 4 databases were accessed for search on 11th of May 2023. MeSH terms were only utilized when searching on PubMed. Table 1 below lists the full search strategy. The term ‘mental health’ was not included in the search strategy in order to include studies on general frequent presentations as well. This is considering that some articles might discuss mental health frequent presentations separately but choose not to include them in the title or abstract.

Studies were included if they:

-

Were original studies that analysed aspects of trends, patterns, and characteristics of frequent presentations to ED with mental health diagnosis.

-

Defined ‘frequent presentation’ as 3 or more ED visits annually or equivalent.

-

Were published between Jan 2000 and April 2023 (23 years approximately).

-

Were in English.

Studies were excluded if they:

-

Were on the paediatric population.

-

Were based in military or non-civilian hospital.

-

Were reviews or editorials.

-

Were not peer-reviewed.

-

Did not have full text available.

-

Limited the scope of psychiatric conditions.

Articles published to before January 2000 were excluded as the criteria for psychiatric diagnosis, and clinical approach has changed significantly over time. The included time frame generated enough publications for the purpose of this review. Paediatric-focused studies were excluded because many of the socio-demographic characteristics of adults are not applicable to the paediatric population. In addition, frequent presentation in the paediatric population is often psycho-somatic in nature and strongly influenced by family factors [9], which is beyond the scope of this review. The consent process of this cohort lies on their parents or legal guardians, which could jeopardize the accuracy of the data collected.

The following two processes were completed by two authors independently, with conflicts resolved by a third person. After the full text review had been completed, included studies were assessed using the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Study Quality Assessment Tools [10]. Reference lists of the full-text studies were screened and added for further screening if deemed appropriate. Data extraction was carried out onto a standardized Excel sheet which included: (1) basic study information (primary author, year of publication, country in which the study was conducted, diagnostic criteria); (2) features related to FP (definition of FP, FP number as % of total ED visitor number vs number of visits made by FP as % of total visits, sample size, FP admission rate); (3) socio-demographic characteristics (gender, age, employment status, marriage status, homelessness, education level); and (4) mental health conditions (top 3 diagnosis, substance use and alcohol dependence history). After initial data extraction, available data were combined to provide an overview of the social and clinical characteristics of FPs. The studies provided different aspects of the social and clinical characteristics of the patients included. Thus, the overall value was calculated based on corresponding available data only.

3 Results

The initial search, as detailed in the Method section, generated 6022 studies, with 2681 identified by Covidence as duplicates. An additional 2 studies were added from citation searching. 3341 studies were screened through title and abstract screening, with 3297 irrelevant studies eliminated. 46 articles 26 were assessed with the full-text review, and 26 were excluded, with the majority reason being that they did not provide or meet frequent presentation criteria (n = 15). The process has been summarised in PRISMA [8] flowchart in Fig. 1. 20 studies were included for the purpose of this review.

All 20 studies can be rated as ‘Good’ based on NHLBI Study Quality Assessment Tools.

Among the 20 studies included published between 2004 and 2022, 6 were from US, 6 from Canada, 4 from Europe and 4 from Australia. 19 studies were retrospective in design and obtained patient data from ED patient record system or equivalent, among which, 1 study [11] combined this data with additional patient interview. Additionally, 1 study [12] is prospective in design and actively recruited patients.

3.1 Sample size and FP definition

Many studies included more than one sample group with different presentation frequencies as a comparison. For the purpose of this review, only the groups that met the inclusion criteria of ‘3 or more times per year or equivalent’ were included in the analysis. The criteria defined in studies that met this criterion varied, ranging from a minimum of ≥ 3 visits/year to a maximum of ≥ 10 visits/year. Many researchers argued that [13] ≥ 4 visits/year should be adopted as universal definition of frequent presentation, with 3 Australian studies included in this review using this as an inclusion criterion. However, multiple recent studies [14,15,16] with large sample sizes defined frequent presentations as ≥ 3 visits/year. Thus, this definition was chosen to maximize the number of articles and FPs that can be included.

The studies included had sample FP size ranging from 13 to 10,969. Overall, 25,688 FP were included in this review, with mean sample size of 1284. Some studies have demonstrated a significant burden to ED from this group of patients, as demonstrated by FP number as percentage of total ED visitor number (0.1–4.4%) vs. number of total visits made by FP as % of total visits (2.0–8.5%).

3.2 Social profile

19 studies (n = 19) provided the gender of the patients; 52% were male and 48% were female. 1 patient was classified as identifying as neither male nor female. 19 studies included the age of the patients, with some expressed as mean or median and others divided by age group. Notably, there are different ways of assigning age groups, this review has adopted the most commonly used method (≤ 20, 21–40, 41–60 and 60 +). 15% of overall patients have an age 20 and below, 47% fall within 21–40, 25% with age 41–60, and 13% are aged 60 and above. Most studies limited their patient group to aged 12 or 18 and above. 1 study only investigated the young population aged 8–26, omitted from population-wise calculations other than gender and FP admission rate. Overall, the average age was 40.7 years.

As for socio-demographic characteristics, on average, 27% of sampled patients were employed (6–54%, n = 9), 20% married (6–31%, n = 5), 41% homeless (16–78%, n = 8) and 17% have education level as tertiary or above (7–47%, n = 4).

3.3 Clinical profile

19 studies included patients’ diagnoses, with 14 specifying the diagnostic criteria used—either ICD 9/10 or DSM IV/V. Notably, some studies have combined certain common diagnoses (such as anxiety and depression) together. For the purpose of this review, the diagnostic category listed under Table 1 is based on DSM-V [17]. The top three diagnostic categories were summarized from each study, with the final calculation of the top three most diagnosed conditions for frequent presenters being: anxiety disorder (44%), depressive disorders (39%) and schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders (33%). Other common diagnostic categories include bipolar and related disorders, ‘substance-related and addictive disorders’ and ‘personality disorders. Substance abuse history, including alcohol dependence, was reported by 15 studies, with a prevalence of 44% among frequent presenters.

4 Discussion

This review provided an overview of the research conducted on FPs with mental health conditions from 2000 to May 2023. Despite significant differences in terms of sample size, FP definition, and aspects of patient characteristics investigated among studies, this review attempted to assess and summarize social-demographic and clinical characteristics of FPs with mental health conditions on a population basis to be able to inform future development of evidence-based interventions to improve the quality of care and reduce the burden on the healthcare system.

4.1 Profiles of FPs

Most studies have included basic profiles such as gender and age. Overall, there is a slightly higher proportion of male FPs (52%), with 14 studies reporting more males than females in their cohort. On a population basis, despite females higher prevalence of mental health conditions than their male counterparts, female tends to have more internalizing disorders (such as depressive disorders and anxiety disorders), whereas male tends to have more externalizing disorders (including attention-deficit, conduct, and substance use disorder), which could potentially explain the relatively higher frequency of ED visits by male [33, 34]. The FPs typically present with suicidality, substance, or alcohol intoxication with or without psychosis, and frequent relapses of symptoms. Additionally, many presents with significant aggression while in ED, adding to the complicity of managing the FPs. Meanwhile, males are less likely to seek mental health help compared to their female counterparts and more likely to become acutely unwell [35, 36], thus resulting in ED presentations. Multiple factors contribute to this phenomenon, including frequent self-medication with drugs and alcohol and social and certain clinicians’ biases toward masculine stereotypes [37].

The majority of studies only reported the number or percentage of one gender (male or female), with the presumption that gender is a binary concept. Only 1 study [31] has included males and females, females and a third category for gender-diverse groups. This could partially be due to a lack of awareness from researchers and clinicians or a lack of precise and inclusive gender data on existing electronic health record (EHR) systems [38, 39]. However, research has shown that gender-diverse group, in general, reports more mental health conditions than their homosexual and cisgender counterparts [40].

Age-wise, 21–40 years old were identified as the most prevalent age group (47%), with a population average of 40.7 years. These results are reasonable since data has shown that mental and behavioural conditions peak in the 15–34 age group (52.8%) and steadily decline as people get older [34]. Interestingly, the peak and median age at onset for any mental disorder were 14.5 years and 18 years, which might suggest that many symptoms tend to be poorly controlled as people grow to middle age, resulting in frequent presentation [41]. Meanwhile, research in Japan has indicated that people aged 20–39 years tend to have the least help-seeking behaviour, leading to severe psychological distress with potentially acute presentations [42]. As people age, however, there tends to be an increase in self-reported mental health symptoms caused by physical illness as people’s resilience to disease [43].

Given their profile, more mental health campaigns could be aimed at males (MOVEMBER for Men), gender diverse (Rainbow Health Australia) and young adult age groups (Orygen Youth Health in Australia) to promote help-seeking behaviour. Given the young average age of onset, early diagnosis by child and adolescents mental health services with early intervention could potentially reduce the number of future presentations.

4.2 Socio-demographic characteristics

Previous studies have identified income, residence, education, marital and employment status as the principal socio-demographic factors associated with mental disorders [44, 45]. In this review, employment status, homelessness, marital and education status were included for analysis.

The overall employment rate was 27% among the FP group. Unemployment has long been established as more prevalent among people with mental health disorders. According to a report published by OECD in 2012 [46], people with severe mental disorders (SMD) are 6–7 times more likely to be unemployed (45–55%) than people without, and those with common mental disorders (CMD) 2–3 times (30–40%). The OECD data is used as a comparison in this review (where available), considering that all studies included were conducted in OECD countries. Unemployment has been associated with an increase in the probability of poor mental health, with the association most prominent in the long-term unemployment group [46]. Unemployed people commonly report feelings of worthlessness and anhedonia and are more commonly diagnosed with chronic depression and anxiety [47]. However, research is less clear on whether there’s a causal relationship between the two factors, and if there is, which resulted in the other [48, 49].

Financial difficulty as a result of unemployment causes homelessness [50, 51], with 41% of the group recorded as homeless at least once when they presented to ED. Whereas the most recent homeless data reported by OECD countries ranges between 0.01 and 0.86% of the nation’s total population [52]. Among the 6 countries included in this review, despite the US topping the homelessness chart with Switzerland being the lowest, it is not reflective of the population homeless data in either country as both the US and Switzerland's homeless rates were 0.18% in 2020 [52]. On the other hand, Australia has a homeless population of 0.48%, the highest among the 6 countries [52]. Studies have indicated that homelessness is both a cause and a result of mental health conditions [53].

People with a tertiary education level and above was 17%, significantly lower than the OECD average of 31–47% from 2004 to 2021 for 25–34 years-old age group and 18–30% in the same period for 55–64 years-old [54]. Studies have shown that better education helps with better access to psychosocial resources, such as a sense of control, resilience, and cultural activities, which all contribute to good mental health [55].

Marital status is another major socio-demographic factor. On a population basis, the number of adults ages 25 to 54 who are married fell from 67% in 1990 to 53% in 2019 in the US [56], which is still significantly higher than the FP group’s marriage rate of 20%. Studies have found that marriage could provide psychological benefits and is a protective factor for mental health [57,58,59]. However, it can be contradictory as sometimes unstable marriage and early marriage can increase distress [60].

From the data above, we can argue that by addressing the existing social challenges such as unemployment, homelessness, poverty, and low education levels, the government is also tackling and reducing the potential mental health crisis experienced by the targeted group of individuals. More mental health education could also be provided at schools, universities, and workplaces to promote awareness. Social welfare institutes could liaise with community mental health teams to provide counselling services for those without employment or home.

4.3 Clinical characteristics

Statistically, it is unsurprising that anxiety disorder (44%) and depressive disorders (39%) top the diagnostic charts as they are also the first and second most prevalent mental health conditions in the US, with population annual prevalence of 19.1% and 8.4% respectively [61]. However, schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders, which represent 33% of frequent presentations, have much lower population prevalence, between 0.25% and 0.64% [61]. It is unsurprising that schizophrenia represents a tiny portion of the population with mental health conditions that present so often. Schizophrenia can present with a wide range of positive and negative symptoms [62], such as hallucinations, delusions, and disturbances in thought and behaviour. Meanwhile, 40% of schizophrenia patients are also affected by depression, 65% affected by anxiety symptoms [63, 64]. All of these contribute to the high presentation rate in this group of patients despite representing a small portion of psychiatry diagnoses in the community. The presentation rate is lower than depression and anxiety, which could be explained by the established community-based care models for schizophrenia that partially reduce the emergency presentations to hospitals [65]. Citing the high prevalence of depression and anxiety in both the community and among the FP group, we urgently need a community-based model for their treatment and management. More training could be provided for general practitioners (GPs) to improve their knowledge of psychiatry.

In many cases, those who presented to ED were brought in by law enforcement agencies against their free will due to patients’ lack of insight [66]. Some presentations of schizophrenia, such as acute psychosis, require timely hospital treatment with multidisciplinary input, which has been associated with lower rehospitalization rates and improved psycho-social skills [67]. It has been well-established that early diagnosis and intervention bring better outcomes [68]. However, developed countries generate much more research in the field than underdeveloped regions; thus, the general consensus might be biased and new studies with new diagnostic criteria and intervention plans might generate different results.

Another frequent diagnosis of FPs reported by frontline ED staff is borderline personality disorder (BPD). However, only 3 studies have identified personality disorder as the top 3 diagnoses. A Spanish study [69] has identified that 9% of total visits to psychiatric emergency services involved a diagnosis of BPD, among which 63% were female, 33% had depression or anxiety, 45% with substance use disorder, and 28% presented with disruptive behaviour. A study in Australia [70] has found similar results, with 15% of BPD patients having concurrent schizophrenia or mood disorder. However, on hospital records, BPD patients only represent less than 2% of total ED presentations in general hospitals, despite the perception that people with BPD are disproportionately reliant on emergency services [70]. A study has found that many psychiatrists are not willing to disclose or document the diagnosis of BPD due to stigma and uncertainty [71]. Meanwhile, frontline ED staff have less training in this field than mental health specialists and might not have enough time to explore the diagnosis. In addition, BPD patients usually present with a diagnosis that is more severe and easier to diagnose, such as the abovementioned substance use disorder, depression, anxiety, and schizophrenia, which are commonly documented. Substance abuse, including alcohol dependence, is widely known to be more prominent in people with mental health conditions. An estimated 2% of the world's population is dependent on alcohol or an illicit drug [80], with a lifetime prevalence of 6.5% for alcohol and 8.9% for substances [81], much lower than the 44% from the FP cohort. 7 studies have included substance-related and addictive disorders as their top 3 diagnoses. Over half of patients with substance and alcohol dependence are associated with co-occurring mental health conditions such as mood disorder, depression and anxiety, and schizophrenia [72, 73], which further contributed to their ED visits on top of their acute toxication episodes.

Bipolar and related mood disorders (BD) are another commonly seen diagnosis in FPs. It is the top 3 diagnosis in 7 out of 20 studies included in this review. More than 2.2 million ED visits were made by patients with BD in the US in 2018, among which 300 thousand patients received BD as the principal diagnosis, with most others present with suicidal ideations, anxiety disorders or substance-related concerns [74]. Unsurprisingly, many of the BD patients come from lower-income households [74]. Another study in Latin America in 2011 [85] also mentioned that BD patients were more likely to report alcohol abuse, ADHD, depression, and panic disorders with significantly higher suicidal ideation than non-BD patients, which potentially predisposes to their frequent presentation.

Given FP’s clinical profile, all of the top 3 conditions identified are manageable in community to prevent acute relapse thus reducing number of hospital presentations. Early diagnosis, early intervention, and continuous follow-up with safety-netting are the keys to keep them away from ED.

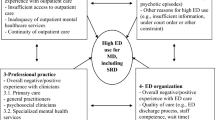

4.4 Influence on care

Many studies have acknowledged the strain on the medical workforce from the FP group with mental health conditions. As illustrated in Table 2, this group of patients tend to use ED resources disproportionally more (as demonstrated by ‘FP number as % of total ED visitor number vs number of visits made by FP as % of total visits’) compared to the general population. Despite frequent presentations, their overall admission rate of 26% is very similar to that of the general population—28% in Australia [1], and 20% in the US [75]. Often, people have longer stay in the ED, causing obstacles for other patients in genuine need to come for help. In Australian settings, 10% of ED mental health presentations had a length of stay longer than 16 h in 2020–2021, much longer than the same measure for all ED presentations of 9 h [2]. The Australian Medical Association (AMA) reported in 2022 that those with mental health admission requirements wait, on average of up to 28 h before admission due to a lack of hospital beds [76]. Some visits could be easily prevented with community support such as GPs, mental health nurses, peer workers or family support. People with mental health distress often find it hard to navigate complex community resources, so they seek ED care where 24-h care is available.

We acknowledge that there are many forms of bias and social stigma on people with mental health conditions, especially in less developed countries. A 2016 report has indicated that mental disorders are subject to the greatest amount and extent of negative judgements and stigmatization, which have long-lasting and devastating effects on patients’ illnesses [77]. Social exclusion and prejudices could also exacerbate their symptoms of mental illness [77]. As a result, many mental health conditions are not diagnosed or treated in their early stages, thus resulting in hospital ED presentation during the acute episode. For FPs, on top of the bias experienced in society, many frontline ED staff have labelled the FP group as ‘frequent flyers’ out of frustration, which partially stems from the lack of management knowledge despite recognizing them as being vulnerable [6]. From the patients’ perspective, many have complained of a lack of empathy from the treating team and felt unappreciated or misunderstood [78]. From the medical system’s perspective, difficulties in resolving the current situation create a ‘revolving-door’ service circle [79], thus resulting in more presentations and frustration from both sides of the medical service, in addition to the financial cost of public medical insurance. Meanwhile, in full-service hospitals, critical emergency resources could be drained away by community-manageable mental health presentations from more urgent conditions such as myocardial infarctions or strokes, which might result in an overall reduction in healthcare outcomes. It is worthwhile to mention that there is a need for a new study to be conducted in Australia on FP to know if there is a change in trend and community perception around the issue and to know how the stigma from ED staff on mental health FPs has changed the presentation pattern over time.

Clearly, there is a significant gap between the demand of community mental health services needed by the FPs and the model or level of care currently provided. This will be addressed under ‘Suggestions’.

4.5 Suggestions

Before we dive into strategies to tackle the current crisis, we recognize the importance of patients present to the ED with the appearance of mental health conditions also to be assessed by general ED physicians to rule out general medical causes of mental health issues, such as delirium or thyroid conditions. Many models to address the FP issue have been proposed in the past [80]. General mental health presentations are a result of acute stressors on top of their long-term socio-demographic disadvantage and clinical conditions. Dedicated mental health triage services and emergency psychiatrists can help reduce bed-block and reserve critical medical resources for patients with general medical conditions. ED staff training can include basic knowledge of dealing with frequently presenting patients, thus reducing frustration. Interventions with inter-professional approach has proven beneficial in FP’s care, with reduction in ED presentation frequencies [81]. For FP with mental health conditions, the multi-disciplinary treating team can include the patient’s treating psychiatrist, psychologist, mental health nurse, social worker, and other healthcare professionals relevant to the patient’s condition.

Despite the importance of reducing ED waiting times and more hospital beds for mental health patients, we strongly advocate for more resources to be allocated to community mental health services with multiple benefits. On a community level, case-based management and a patient-centred approach can be tailored to specific patients’ needs, with a higher rate of patient satisfaction, better clinical outcomes, and reduced ED visits and admissions [82, 83]. Nursing models such as the Buurtzorg [84] could be expanded to provide mental health support and social welfare services at a local level. In Australia, the Royal Commission on Victoria’s Mental Health System [85] (the Commission) has recommended integrating mental health and wellbeing services into local communities with a regionalised governance body.

In case of a mental health crisis, the Commission recommended 24-h telehealth services that provide triage and emergency support. Such services have been made available in many developed countries like Australia (Lifeline, Beyond Blue), Canada (Talk Suicide Canada), and the US (988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline) etc., with most being 24/7 and toll-free. However, many developing countries still lack dedicated suicide prevention services staffed by mental health professionals. Many authorities refer people at crisis to emergency police lines, which are not necessarily staffed by people good at mental health crisis management. Such hotline services could be complemented by outreach services from peer workers on site and followed up by mental health professionals. Community wellbeing centres and domestic violence services can provide safe spaces and crisis respite facilities, which play the role of hospital ED to reduce unnecessary presentations, thus improving the overall quality of care in ED. Social housing programs, financial assistance for the unemployed, and better education infrastructure could reduce the incidence of mental health conditions by addressing the identified risk factors for frequent presentations. Involuntary treatment orders should always be considered as a measure of last resort, with thorough police training delivered by clinicians. Mental health services and law enforcement agencies could also engage in community education on related regulations to promote awareness.

Funding is the key to all policies and medical treatment. An OECD report from 2021 indicated that mental ill-health drives economic costs of more than 4% of countries GDP [86]. The report has praised countries like Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Norway and the UK for leading the mental health campaign [86]. However, despite the growing attention, OECD countries, in general, have not significantly increased funding for mental health in the past [86]. Given the Australian example, government spending on mental health-related services increased by an average rate of 4% annually between 2016–2017 and 2020–2021, with an average annual increase of only 2.8% in real terms [87]. This has led to the AMA statement in 2018 claiming that ‘mental health and psychiatric care is grossly underfunded when compared to physical health’ in Australia [88]. A similar situation is seen in Canada, where the Canadian Mental Health Association criticized the nation’s Budget 2023 being ‘out of touch with mental health crisis’ [89]. In addition, as identified by this review, 44% of the FPs with mental health conditions have a history of substance abuse. Resources for addiction treatment could also be another area of major investment to consider by the future government budget.

4.6 Limitations and implications on future research

There are several limitations to this review. First, only English publications with available full texts were included (conference abstracts without full texts articles published in English were excluded), which could lead to language and accessibility bias. Second, as mentioned above, few studies have included gender-diverse grouping in their patient profile. Given the prevalence of mental health issues among the group [40], future studies and electronic health records should take this into account. Third, there are significant differences in frequent presentation definitions among different studies. Most studies have defined frequent presentation as 3 or 4 more visits per year, with some others defining the criteria on a monthly basis. As such, patients with different presentation frequencies were analysed together in this review. However, those who present 10 times a year more may have a different social or clinical profile than those who present 4 times a year. Standardized approach to define frequent presentations should be adopted in the future. In addition, studies sampled limited and different aspects of the socio-demographic or clinical profiles of their respective patient cohort. This review only included the most relevant aspects, but there are many others worth analysing, such as patients’ source of referral, primary care usage, and past admission history. Moreover, most studies did not include the acute stressors that prompt patients’ ED visits or their utilization of community resources such as general practitioners or private psychiatrists. Future studies could include as many aspects of patients’ profiles as possible. This could be helpful in identifying the immediate need and predisposing factor of their presentations. Different diagnostic tools used also add to the difficulties in standardized analysis. A gold standard and regulated version of mental health diagnostic tools should be developed and implemented. The goal of these strategies is to facilitate mental health care on a community level to reduce the number of presentations, thus promoting the overall healthcare outcome.

5 Conclusion

Frequent presenters with mental health condition utilize the emergency medical services disproportionally compared to the general public. This review is one of the first studies that summarized the profile, socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of FPs with mental health conditions. On average, FPs are middle aged and equally prevalent in both gender. Current data lacks representation for gender diverse group. They are significantly associated with high rate of unemployment, homelessness, lower than average education level, and being single. Anxiety disorder, depressive disorder, and schizophrenia spectrum disorders are the most common clinical diagnosis associated with the group. However, we also acknowledge the limitations of this review, stemming from the exclusion of non-English articles, difference in frequent presentation definition and a lack of standardized approach to define and analyse this unique group of patients. Based on our findings, we have made recommendations to improve care for this group of patients, including ED staff training, better community mental health resourcing, 24/7 telehealth hotline service, and stronger government funding on mental health. This review serves as starting point for those looking to develop a care model addressing the frequent presentation issue and improving the overall health outcomes from emergency department utilization.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- AMA:

-

Australian Medical Association

- BD:

-

Bipolar disorder

- CMD:

-

Common mental disorders

- DSM:

-

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders

- ED:

-

Emergency Department

- EHR:

-

Electronic health record

- FPs:

-

Frequent presenters

- ICD:

-

International classification of diseases

- MeSH:

-

Medical subject headings

- NHLBI:

-

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute

- OECD:

-

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- SES:

-

Socio-economic status

- SMD:

-

Severe mental disorders

- WOS:

-

Web of science

References

Emergency department care activity. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/myhospitals/intersection/activity/ed#:~:text=In%202021-22%3A,were%20Admitted%20to%20this%20hospital. Accessed 17 June 2023.

Mental health services provided in emergency departments. https://www.aihw.gov.au/mental-health/topic-areas/emergency-departments. Accessed 17 June 2023.

Shehada ER, He L, Eikey EV, Jen M, Wong A, Young SD, Zheng K. Characterizing frequent flyers of an emergency department using cluster analysis. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2019;264:158–62. https://doi.org/10.3233/shti190203.

LaCalle E, Rabin E. Frequent users of emergency departments: the myths, the data, and the policy implications. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:42–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.01.032.

Slankamenac K, Zehnder M, Langner TO, Krähenmann K, Keller DI. Recurrent emergency department users: two categories with different risk profiles. J Clin Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8030333.

Chastonay OJ, Lemoine M, Grazioli VS, Canepa Allen M, Kasztura M, Moullin JC, Daeppen JB, Hugli O, Bodenmann P. Health care providers’ perception of the frequent emergency department user issue and of targeted case management interventions: a cross-sectional national survey in Switzerland. BMC Emerg Med. 2021;21:4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-020-00397-w.

Judkins S, Fatovich D, Ballenden N, Maher H. Mental health patients in emergency departments are suffering: the national failure and shame of the current system: a report on the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine’s Mental Health in the Emergency Department Summit. Australas Psychiatry. 2019;27:615–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856219852282.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021;18: e1003583. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583.

Leon SL, Polihronis C, Cloutier P, Zemek R, Newton AS, Gray C, Cappelli M. Family factors and repeat pediatric emergency department visits for mental health: a retrospective cohort study. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;28:9–20.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Study Quality Assessment Tools|NHLBI, NIH. 2021. Accessed 1 June 2023. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools.

Mehl-Madrona LE. Prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses among frequent users of rural emergency medical services. Can J Rural Med. 2008;13:22–30.

Arfken CL, Zeman LL, Yeager L, White A, Mischel E, Amirsadri A. Case-control study of frequent visitors to an urban psychiatric emergency service. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:295–301. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.55.3.295.

Locker TE, Baston S, Mason SM, Nicholl J. Defining frequent use of an urban emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2007;24:398–401. https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.2006.043844.

Fleury MJ, Rochette L, Grenier G, Huynh C, Vasiliadis HM, Pelletier E, Lesage A. Factors associated with emergency department use for mental health reasons among low, moderate and high users. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2019;60:111–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2019.07.006.

Gentil L, Grenier G, Vasiliadis HM, Huynh C, Fleury MJ. Predictors of recurrent high emergency department use among patients with mental disorders. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094559.

Armoon B, Cao ZR, Grenier G, Meng XF, Fleury MJ. Profiles of high emergency department users with mental disorders. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;54:131–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2022.01.052.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Pasic J, Russo J, Roy-Byrne P. High utilizers of psychiatric emergency services. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:678–84. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.56.6.678.

Ledoux Y, Minner P. Occasional and frequent repeaters in a psychiatric emergency room. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41:115–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-005-0010-6.

Brunero S, Fairbrother G, Lee S, Davis M. Clinical characteristics of people with mental health problems who frequently attend an Australian emergency department. Aust Health Rev. 2007;31:462–70. https://doi.org/10.1071/ah070462.

Wooden MD, Air TM, Schrader GD, Wieland B, Goldney RD. Frequent attenders with mental disorders at a general hospital emergency department. Emerg Med Australas. 2009;21:191–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-6723.2009.01181.x.

Vandyk AD, VanDenKerkhof EG, Graham ID, Harrison MB. Profiling frequent presenters to the emergency department for mental health complaints: socio-demographic, clinical, and service use characteristics. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2014;28:420–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2014.09.001.

Brennan JJ, Chan TC, Hsia RY, Wilson MP, Castillo EM. Emergency department utilization among frequent users with psychiatric visits. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:1015–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12453.

Chang G, Weiss AP, Orav EJ, Rauch SL. Predictors of frequent emergency department use among patients with psychiatric illness. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:716–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.09.010.

Vu F, Daeppen JB, Hugli O, Iglesias K, Stucki S, Paroz S, Canepa Allen M, Bodenmann P. Screening of mental health and substance users in frequent users of a general Swiss emergency department. BMC Emerg Med. 2015;15:27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-015-0053-2.

Richard-Lepouriel H, Weber K, Baertschi M, DiGiorgio S, Sarasin F, Canuto A. Predictors of recurrent use of psychiatric emergency services. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66:521–6. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400097.

Sirotich F, Durbin A, Durbin J. Examining the need profiles of patients with multiple emergency department visits for mental health reasons: a cross-sectional study. Soc Psychiatr Psychiatry Epidemiol. 2016;51:777–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1188-5.

Buhumaid R, Riley J, Sattarian M, Bregman B, Blanchard J. Characteristics of frequent users of the emergency department with psychiatric conditions. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26:941–50. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2015.0079.

Meng X, Muggli T, Baetz M, D’Arcy C. Disordered lives: life circumstances and clinical characteristics of very frequent users of emergency departments for primary mental health complaints. Psychiatry Res. 2017;252:9–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.02.044.

Slankamenac K, Heidelberger R, Keller DI. Prediction of recurrent emergency department visits in patients with mental disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00048.

Casey M, Perera D, Enticott J, Vo H, Cubra S, Gravell A, Waerea M, Habib G. High utilisers of emergency departments: the profile and journey of patients with mental health issues. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2021;25:316–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13651501.2021.1904998.

Cullen P, Leong RN, Liu B, Walker N, Steinbeck K, Ivers R, Dinh M. Returning to the emergency department: a retrospective analysis of mental health re-presentations among young people in New South Wales, Australia. BMJ Open. 2022;12: e057388. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057388.

Boyd A, Van de Velde S, Vilagut G, de Graaf R, O’Neill S, Florescu S, Alonso J, Kovess-Masfety V. Gender differences in mental disorders and suicidality in Europe: results from a large cross-sectional population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2015;173:245–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.11.002.

Health conditions prevalence. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/health-conditions-prevalence/2020-21. Accessed 11 June 2023.

Chatmon BN. Males and mental health stigma. Am J Mens Health. 2020;14:1557988320949322. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988320949322.

Parent MC, Hammer JH, Bradstreet TC, Schwartz EN, Jobe T. Men’s mental health help-seeking behaviors: an intersectional analysis. Am J Mens Health. 2018;12:64–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988315625776.

Sagar-Ouriaghli I, Godfrey E, Bridge L, Meade L, Brown JSL. Improving mental health service utilization among men: a systematic review and synthesis of behavior change techniques within interventions targeting help-seeking. Am J Mens Health. 2019;13:1557988319857009. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988319857009.

Lau F, Antonio M, Davison K, Queen R, Devor A. A rapid review of gender, sex, and sexual orientation documentation in electronic health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27:1774–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaa158.

Cahill S, Makadon H. Sexual orientation and gender identity data collection in clinical settings and in electronic health records: a key to ending LGBT health disparities. LGBT Health. 2014;1:34–41. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2013.0001.

Taylor J, Power J, Smith E, Rathbone M. Bisexual mental health and gender diversity: findings from the ‘Who I Am’ study. Aust J Gen Pract. 2020;49:392–9.

Solmi M, Radua J, Olivola M, Croce E, Soardo L, de Pablo GS, Il Shin J, Kirkbride JB, Jones P, Kim JH, et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:281–95. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01161-7.

Yamauchi T, Suka M, Yanagisawa H. Help-seeking behavior and psychological distress by age in a nationally representative sample of Japanese employees. J Epidemiol. 2020;30:237–43. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20190042.

Lorem GF, Schirmer H, Wang CEA, Emaus N. Ageing and mental health: changes in self-reported health due to physical illness and mental health status with consecutive cross-sectional analyses. BMJ Open. 2017;7: e013629. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013629.

Hubbard G, den Daas C, Johnston M, Dixon D. Sociodemographic and psychological risk factors for anxiety and depression: findings from the Covid-19 health and adherence research in Scotland on Mental Health (CHARIS-MH) cross-sectional survey. Int J Behav Med. 2021;28:788–800. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-021-09967-z.

Fleury M-J, Grenier G, Bamvita J-M, Perreault M, Jean C. Typology of adults diagnosed with mental disorders based on socio-demographics and clinical and service use characteristics. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:67. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-11-67.

Junna L, Moustgaard H, Martikainen P. Current unemployment, unemployment history, and mental health: a fixed-effects model approach. Am J Epidemiol. 2022;191:1459–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwac077.

Farré L, Fasani F, Mueller H. Feeling useless: the effect of unemployment on mental health in the Great Recession. IZA J Labor Econ. 2018;7:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40172-018-0068-5.

Owen K, Watson N. Unemployment and mental health. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 1995;2:63–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.1995.tb00145.x.

Bartelink VHM, Zay Ya K, Guldbrandsson K, Bremberg S. Unemployment among young people and mental health: a systematic review. Scand J Public Health. 2020;48:544–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494819852847.

AIHW media releases. https://www.aihw.gov.au/news-media/media-releases/2002/oct/financial-difficulty-most-common-reason-for-homele. Accessed 11 June 2023.

Ryu S, Fan L. The relationship between financial worries and psychological distress among U.S. adults. J Fam Econ Issues. 2023;44:16–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-022-09820-9.

OECD. OECD affordable housing database. https://www.oecd.org/housing/data/affordable-housing-database/. Accessed 11 June 2023.

Johnson G, Chamberlain C. Are the homeless mentally ill? Aust J Soc Issues. 2011;46:29–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1839-4655.2011.tb00204.x.

OECD. Population with tertiary education. https://data.oecd.org/eduatt/population-with-tertiary-education.htm. Accessed 11 June 2023.

Niemeyer H, Bieda A, Michalak J, Schneider S, Margraf J. Education and mental health: do psychosocial resources matter? SSM Popul Health. 2019;7:100392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100392.

Fry R, Parker K. Rising share of U.S. adults are living without a spouse or partner. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2021/10/05/rising-share-of-u-s-adults-are-living-without-a-spouse-or-partner/#fnref-31655-3. Accessed 11 June 2023.

Jace CE, Makridis CA. Does marriage protect mental health? Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc Sci Q. 2021;102:2499–515. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.13063.

Williams DR, Takeuchi D, Adair R. Marital status and psychiatric disorders among blacks and whites. J Health Soc Behav. 1992;33:140–57.

Carlson DL, Kail BL. Socioeconomic variation in the association of marriage with depressive symptoms. Soc Sci Res. 2018;71:85–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2017.12.008.

Hynek KA, Abebe DS, Liefbroer AC, Hauge LJ, Straiton ML. The association between early marriage and mental disorder among young migrant and non-migrant women: a Norwegian register-based study. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22:258. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01836-5.

Statistics. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics. Accessed 12 June 2023.

Hany M, Rehman B, Azhar Y, Chapman J. Schizophrenia. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing LLC; 2023.

Conley RR, Ascher-Svanum H, Zhu B, Faries DE, Kinon BJ. The burden of depressive symptoms in the long-term treatment of patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2007;90:186–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2006.09.027.

Temmingh H, Stein DJ. Anxiety in patients with schizophrenia: epidemiology and management. CNS Drugs. 2015;29:819–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-015-0282-7.

Gowda GS, Isaac MK. Models of care of schizophrenia in the community—an international perspective. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2022;24:195–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-022-01329-0.

Light E. Rates of use of community treatment orders in Australia. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2019;64:83–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2019.02.006.

Dixon LB, Dickerson F, Bellack AS, Bennett M, Dickinson D, Goldberg RW, Lehman A, Tenhula WN, Calmes C, Pasillas RM, et al. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychosocial treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:48–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbp115.

Larsen TK, Melle I, Auestad B, Haahr U, Joa I, Johannessen JO, Opjordsmoen S, Rund BR, Rossberg JI, Simonsen E, et al. Early detection of psychosis: positive effects on 5-year outcome. Psychol Med. 2011;41:1461–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291710002023.

Pascual JC, Córcoles D, Castaño J, Ginés JM, Gurrea A, Martín-Santos R, Garcia-Ribera C, Pérez V, Bulbena A. Hospitalization and pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder in a psychiatric emergency service. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:1199–204. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2007.58.9.1199.

Broadbear JH, Rotella JA, Lorenze D, Rao S. Emergency department utilisation by patients with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder: an acute response to a chronic disorder. Emerg Med Australas. 2022;34:731–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/1742-6723.13970.

Sisti D, Segal AG, Siegel AM, Johnson R, Gunderson J. Diagnosing, disclosing, and documenting borderline personality disorder: a survey of psychiatrists’ practices. J Pers Disord. 2016;30:848–56. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi_2015_29_228.

Kingston REF, Marel C, Mills KL. A systematic review of the prevalence of comorbid mental health disorders in people presenting for substance use treatment in Australia. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2017;36:527–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12448.

Flynn PM, Brown BS. Co-occurring disorders in substance abuse treatment: issues and prospects. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;34:36–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2006.11.013.

Eseaton PO, Oladunjoye AF, Anugwom G, Onyeaka H, Edigin E, Osiezagha K. Emergency department utilization by patients with bipolar disorder: a national population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2022;313:232–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.06.086.

Venkatesh AK, Dai Y, Ross JS, Schuur JD, Capp R, Krumholz HM. Variation in US hospital emergency department admission rates by clinical condition. Med Care. 2015;53:237–44. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000000261.

Health system failing those with poor mental health. https://www.ama.com.au/media/health-system-failing-those-poor-mental-health. Accessed 22 July 2023.

Rössler W. The stigma of mental disorders: a millennia-long history of social exclusion and prejudices. EMBO Rep. 2016;17:1250–3. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.201643041.

Mautner DB, Pang H, Brenner JC, Shea JA, Gross KS, Frasso R, Cannuscio CC. Generating hypotheses about care needs of high utilizers: lessons from patient interviews. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16(Suppl 1):S26-33. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2013.0033.

Huhtakangas M, Tuomikoski A, Kyngäs H, Kanste O. Frequent attenders experiences of encounters with healthcare personnel: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Nursing & Health Sciences 2021;23:53-68. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12784.

Mao W, Shalaby R, Agyapong VIO. Interventions to reduce repeat presentations to hospital emergency departments for mental health concerns: a scoping review of the literature. Healthcare. 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11081161.

Adam P, Brandenburg DL, Bremer KL, Nordstrom DL. Effects of team care of frequent attenders on patients and physicians. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28:247–57. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020944.

Altin SV, Stock S. The impact of health literacy, patient-centered communication and shared decision-making on patients’ satisfaction with care received in German primary care practices. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:450. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1693-y.

Gonçalves S, von Hafe F, Martins F, Menino C, Guimarães MJ, Mesquita A, Sampaio S, Londral AR. Case management intervention of high users of the emergency department of a Portuguese hospital: a before-after design analysis. BMC Emerg Med. 2022;22:159. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-022-00716-3.

Beckers T, Koekkoek B, Hutschemaekers G, Tiemens B. Potential predictive factors for successful referral from specialist mental-health services to less intensive treatment: a concept mapping study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13: e0199668. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0199668.

Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System Final Report; Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System: 2 March 2021, 2021.

OECD. A new benchmark for mental health systems. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2021. https://doi.org/10.1787/4ed890f6-en.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Expenditure on mental health-related services. Accessed 11 June 2023. https://www.aihw.gov.au/mental-health/topic-areas/expenditure.

Australian Medical Association. POSITION STATEMENT on Mental Health—2018. AMA: Australia. 2018.

Canadian Mental Health Association. Budget 2023 out of touch with mental health crisis. CMHA. 2023.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Z. wrote the main manuscript text, S.D. proofread and provided guidance.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

No competing interests or funding were involved in this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Z., Das, S. Unveiling the patterns: exploring social and clinical characteristics of frequent mental health visits to the emergency department—a comprehensive systematic review. Discov Ment Health 4, 17 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44192-024-00070-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44192-024-00070-9