Abstract

Determinants at the contextual level are important for children’s and adolescents’ mental health care utilization, as this is the level where policy makers and care providers can intervene to improve access to and provision of care. The objective of this review was to summarize the evidence on contextual determinants associated with mental health care utilization in children and adolescents. A systematic literature search in five electronic databases was conducted in August 2021 and retrieved 6439 unique records. Based on eight inclusion criteria, 74 studies were included. Most studies were rated as high quality (79.7%) and adjusted for mental health problems (66.2%). The determinants that were identified were categorized into four levels: organizational, community, public policy or macro-environmental. There was evidence of a positive association between mental health care utilization and having access to a school-based health center, region of residence, living in an urban area, living in an area with high accessibility of mental health care, living in an area with high socio-economic status, having a mental health parity law, a mental health screening program, fee-for-service plan (compared to managed care plan), extension of health insurance coverage and collaboration between organizations providing care. For the other 35 determinants, only limited evidence was available. To conclude, this systematic review identifies ten contextual determinants of children’s and adolescents’ mental health care utilization, which can be influenced by policymakers and care providers. Implications and future directions for research are discussed

PROSPERO ID: CRD42021276033.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Childhood and adolescence are critical phases in life for mental health. The onset of a first mental disorder occurs before age 14 in one-third of individuals, age 18 in almost half, and before age 25 in more than half of individuals [1]. A recent systematic review of high-income countries shows an overall prevalence of any childhood mental disorder of 13% [2]. The consequences of mental disorders include a negative impact on quality of life [3] and the development of school careers [4,5,6]. These disorders can even continue into adulthood [7] and may be related to worse employment outcomes [8, 9]. Apart from the individual burden of mental disorders for children and adolescents, there is also a collective social and economic burden [10, 11]. For instance, children with mental disorders may be more often involved in crime, have extra educational needs or are more likely to end up in foster care or residential care compared to children without mental disorders [12]. Despite the high prevalence and negative consequences of mental disorders in children and adolescents, many do not receive any services to deal with or reduce these disorders [2, 13, 14].

Effective prevention and early intervention strategies for mental disorders have the potential to significantly reduce the burden of disease and improve an individual’s quality of life [15, 16]. However, to develop such strategies, it is crucial to properly understand which factors contribute to children’s and adolescents’ service use. Andersen et al. [17] created the Behavioural Model of Health Service use, a theoretical framework of health service use including individual and contextual determinants. Associations of mental health service use with determinants at the individual level such as age, gender, ethnicity, and family situation have been summarized in earlier systematic reviews. For example, Elster et al. [18] performed a review on racial and ethnic disparities in care utilization among adolescents and the review by Ryan et al. [19] focused on family-related factors in associations with mental health service use. Besides determinants on the individual and family level, determinants on broader contextual levels have been shown to also explain mental health service use.

However, summarized evidence on contextual determinants of mental health service use, such as health organization and provider-related factors, is scarce and the systematic reviews available have very specific topics or study populations. The systematic review by Werlen et al. [20] is limited to interventions to improve children's access to mental health care at both the individual and contextual level. The systematic review by So et al. summarizes the evidence on policy levers to promote access to and utilization of children’s mental health services, limited to the United States of America (U.S.A.) [21]. The systematic review by Eijgermans et al. summarizes individual-level and contextual determinants associated with mental health care utilization [22]. However, this review solely included longitudinal, population-based studies.

This systematic review aims to identify, summarize and discuss all available evidence from studies on contextual determinants of mental health care utilization in children and adolescents. In this review, mental health care is defined as inpatient and outpatient services and medication use to treat mental, behavioral and emotional problems. Contextual determinants are grouped according to McLeroy’s ecological model [23]. This is a conceptual framework that distinguishes different layers surrounding an individual. In our review, we focus on layers beyond the individual and family level. These layers consist of contextual determinants that are beyond individual control, and influence multiple unrelated children, such as the school or the community, and more distal public policy. The last and most distant layer comprises macro-environmental determinants that are more difficult to influence, e.g. climate. Many contextual determinants can be influenced by or are the responsibility of policymakers and care providers. Insight into which contextual determinants influence mental health care utilization will enable care providers and policy makers to improve access to and provision of care and decrease treatment gaps in their populations. Furthermore, this knowledge can contribute to the development of preventive strategies and give directions for future research on this topic.

Methods

Literature search

This review was conducted and reported in accordance with the PRISMA statement [24] and was registered at PROSPERO (ID: CRD42021276033) on August 30, 2021. An experienced information specialist from Erasmus Medical Centre (WB) created and performed the search in five databases (Embase via Embase.com, MEDLINE ALL via Ovid, Web of Science Core Collection, the Cochrane Library CENTRAL register of Trials via Wiley and PsycINFO via Ovid). Studies examining the association between any contextual factor and children’s and adolescent’s mental health care utilization were identified from database inception until August 31, 2021 (date last searched). To capture all relevant studies, we deliberately used a broad search strategy using terms related to mental health care or psychotherapy, children or adolescents, health care utilization or therapy enrollment, and study types (controlled, cohort and international studies). We did not apply any restrictions on date but excluded non-English language articles and conference abstracts. The search can be found in Supplement 1. The search is similar to the search of a previous systematic review [22]. However, different study selection criteria were applied in both reviews. In contrast to the previous systematic review, in the current systematic review, we did not restrict the selection criteria to longitudinal, population-based studies. To identify additional relevant studies, we checked the reference lists of the studies included in the current review and other relevant systematic reviews. All articles were imported in EndNote and de-duplicated with the method by Bramer et al. [25].

Study selection criteria

For inclusion in the review, studies had to meet all of the following selection criteria:

-

(i)

Language: the full text is written in English;

-

(ii)

Study type: the study is quantitative, empirical, peer-reviewed, and published in a scientific journal;

-

(iii)

Study population: the study population is children under the age of 18 years, or a population with a mean age under 18 years and no participants over the age of 21;

-

(iv)

Geographic region: the study population is living in a Western geographical region, this to increase the comparability among studies in an already broad systematic review. Contextual determinants might be different in non-Western countries [26]. Western geographical region includes Europe (except Turkey), Northern America (the U.S.A. and Canada) and Oceania (Australia and New Zealand);

-

(v)

Outcome: the outcome of the study has to be mental health care defined as inpatient and outpatient services and medication use for the treatment of mental, behavioral and emotional problems;

-

(vi)

Determinant: the determinant has to be a contextual factor that is beyond individual control, and has an influence on multiple unrelated children. All individual or family-related determinants were excluded;

-

(vii)

Comparison group: a comparison group or reference group using no care has to be part of the study;

-

(viii)

Statistical analysis: a statistical analysis assessing an association must be performed.

Using these criteria, two reviewers (SV and DE) independently screened titles and abstracts for eligibility. In case of disagreement, a decision was made by consensus or the study was included for full-text evaluation. Hereafter, two reviewers (SV and DE) assessed the full-text of the remaining studies with the same criteria. During the full-text evaluation, there were seven cases of disagreement, for which a third reviewer (WJ) was consulted.

Data extraction

Using a predesigned form, the following data were extracted as characteristics of the included studies: first author, year of publication, country, study design, number of participants, database, type of study population, age, type of mental health care and reporter of mental health care utilization. Regarding the studied determinants, the following data were extracted: the determinant studied in association with mental health care utilization, whether this association was significant and if so, the direction and measure of the association, and if applicable, any subgroup findings and whether or not the association was adjusted for mental health problems. This process was completed by one researcher (SV). A random selection of 8 studies (10%) was assessed by a second researcher (DE) with almost perfect inter-rater agreement (Kappa = 0.88) [27].

Quality assessment

For quality assessment of the included studies, the QualSyst tool of Kmet et al. [28] was used. In this checklist, 14 items are listed, which were scored with 2 (yes), 1 (partial), or 0 points (no) each. To calculate the quality score per study, all scores were added together and divided by the total possible sum. This process was completed by one researcher (DE). A random selection of 8 studies (10%) was assessed by a second researcher (SV) with almost perfect inter-rater agreement (Kappa = 0.86) [27]. Based on this final score, the quality of the study was rated high (≥ 0.80), medium (≥ 0.60 and < 0.80), or low (< 0.60). These cutoffs are in line with other studies that used the QualSyst Tool [29,30,31].

Data synthesis

Identified determinants were categorized according to a slightly modified version of McLeroy’s widely used ecological model, comprising three contextual levels surrounding an individual, beyond the individual and interpersonal level (Fig. 1) [23]. The first is the organizational level, including determinants that are related to institutions visited by an individual, such as school or a sports club. The second is the community level, including determinants that are related to the community and neighborhood where an individual lives, such as its physical environment, availability of services or the quality of relationships within the neighborhood. The third is the public policy level, including determinants that are related to national and/or regional policies and the organization of care. Examples are national or state-wide laws, financial structures for the provision of care and the extent of collaboration between health care providers. For the purpose of this review, a fourth level was added. This level is the macro-environmental, including determinants that are difficult to control, such as weather conditions, seasons and national Holidays.

To summarize the evidence on the association of contextual determinants and children’s and adolescents’ mental health care utilization, a previously established method was used [32,33,34]. The number of studies that reported a significant association in the same direction between a contextual determinant and mental health care utilization was divided by the total number of studies that examined that determinant. Determinants investigated by four or more studies were coded as: no association (00) when 0–33% of studies found a significant association in the same direction; inconsistent association (??) when 34–59% of studies found a significant association in the same direction; positive (+ +) or negative (− −) association when 60–100% of studies found a significant association in the same direction. Determinants investigated by three studies or less were coded as limited evidence. To provide insight in the direction of the limited evidence, the same criteria were applied to the determinants investigated by four or more studies, but only with one symbol (i.e., 0, ?, + and −). The rules for classifying the level of evidence are summarized in Table 1. There are three notes to this classification: 1) if multiple studies from one database assessed the same contextual determinant, this counts as one study in summarizing the evidence; 2) if a study reports both an association and no association (e.g., when the determinant is associated with outpatient care, but not with inpatient), the association outweighs no association; and 3) if the number of studies reporting a positive and negative association was equal, and based on above rules would be labelled as evidence of a positive or negative association, the determinant was nevertheless coded as inconsistent evidence.

Results

Study identification and selection

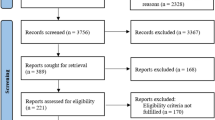

The flowchart of study selection is presented in Fig. 2. In total, 10,479 potentially relevant studies were identified. After de-duplication, 6439 studies were screened on title and abstract, which resulted in 153 eligible studies for full-text screening. Of those, 74 studies met the selection criteria and were included in the review [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108].

Characteristics of the included studies

The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 2. The majority of the included studies were conducted in the U.S.A. (83.8%) and were published in 2010 or later (63.5%). In addition, 71.3% of the included studies were conducted with a longitudinal, experimental or quasi-experimental design. The number of participants varied widely, ranging from fewer than 100 participants to more than 1,000,000 participants. No studies were conducted solely among children in early childhood (0–3 years old) and more than half of the studies (60.8%) included a broad age range covering more than one age category (e.g., childhood and adolescence). Approximately one-third of the included studies (35.1%) were performed in a general population, the other studies were performed in specific populations such as children with mental health problems or using any type of care (35.1%), children from low-income families (14.9%), children involved in the child welfare system (4.1%), children with disabilities (2.7%) or a combination of these specific groups (5.4%). Various types of mental health care were assessed in the included studies, mostly a combination of inpatient and outpatient (33.8%) or outpatient only (27.0%), whereby half of the studies (50.0%) used administrative data. Approximately two-thirds (66.2%) of the studies adjusted for (the level of) mental health problems in the studied associations. Detailed information on the characteristics of the included studies can be found in Supplement 2.

Quality assessment

Most studies (79.7%) were rated as high quality, the remaining studies were rated as moderate quality. No studies received a low-quality score. The items “description of the study design” and “method of subject selection” most often scored poorly. Detailed information on the quality assessment can be found in Supplement 3.

Contextual determinants associated with mental health care utilization

Table 3 provides an overview of all contextual determinants of mental health care utilization in children and adolescents that were investigated in the 74 studies. Studies that were both rated as high quality and adjusted for mental health problems are presented in bold, hereafter referred to as high-quality well-adjusted studies. In total, 45 determinants were identified, of which 35 with limited evidence (77.7%). Results are presented according to levels of McLeroy’s modified ecological model: organizational, community, public policy and macro-environmental (Fig. 1) [23].

Organizational level

Twelve studies reported on 16 different determinants at the organizational level. Four of these studies were classified as high quality and adjusted for mental health problems. There was evidence for a positive association between having access to a school-based health center and mental health care utilization (5/6 studies). Of these six studies, only one was a high-quality well-adjusted study. All other 15 determinants had limited evidence (Table 3).

Community level

Thirty-two studies reported on 9 determinants at the community level. Sixteen of these studies were classified as high quality and adjusted for mental health problems. Evidence for an association was found for the region of residence (8/10 studies). Six out of these ten studies were high quality and well-adjusted. Evidence for a positive association was found for high accessibility of services (5/8 studies; with 6/8 high-quality well-adjusted studies), living in an urban area (13/15 studies; with 7/15 high-quality well-adjusted studies) and living in an area with a high socio-economic status (5/9 studies; with 6/9 high-quality well-adjusted studies; multiple studies from one database count as one in summarizing the evidence). All other five determinants had limited evidence (Table 3).

Public policy level

Thirty-six studies reported on 12 determinants at the public policy level. Twenty-seven of these studies were classified as high quality and adjusted for mental health problems. There was evidence for a positive association for implementing a parity law (i.e., treating the reimbursement of mental health care costs the same as other health care costs) (5/7 studies; with 7/7 high-quality well-adjusted studies), a mental health screening program (4/5 studies; with 2/5 high-quality well-adjusted studies), collaboration between health service providers (3/5 studies; with 4/5 high-quality well-adjusted studies), a fee-for-service plan compared to a managed care plan (3/4 studies; with 3/4 high-quality well-adjusted studies) and an expansion of health insurance (4/6 studies; with 4/6 high-quality well-adjusted studies). All other seven determinants had limited evidence (Table 3).

Macro-environmental level

There were two studies examining eight determinants at the macro-environmental level, of which one was a high-quality well-adjusted study. All eight determinants had limited evidence.

Discussion

This review aimed to summarize the evidence of contextual determinants associated with mental health care utilization in children and adolescents. In total, 45 determinants at the organizational, community, public policy and macro-environmental level were identified and for ten determinants evidence was found of an association with mental health care utilization in children and adolescents. Evidence for an association was found for having access to a school-based health center, region of residence, living in an urban area, living in an area with a high accessibility of mental health care, living in an area with a high socio-economic status, having a mental health parity law, a mental health screening program, collaboration between care provider organizations, fee-for-service plan (compared to a managed care plan) and extension of health insurance. These determinants were found in mostly high-quality well-adjusted studies, except for having access to a school-based health center, where only one study was of high quality and well-adjusted. For the other 35 identified determinants, the evidence was limited.

Organizational level

At the organizational level, there was evidence for a positive association between having access to a school-based mental health center and mental health care utilization [67, 68, 75, 92, 106], but the quality and level of adjustment of the underlying studies were limited. Usually, children do not seek mental health care on their own but depend on caregivers, teachers or other adults to seek mental health care for them [109]. School-based health centers might play an important role in the access to mental health care since school health professionals are often the first professionals that are contacted when children have mental health problems [110]. Furthermore, school-based health center professionals receive specialized training for the identification of mental health problems in school-aged youth [75]. Children and adolescents in schools with a school-based health center benefit in terms of accessibility by receiving either on-site mental health screening and counseling services or by being referred to mental health services outside the school [17]. In addition, school-based health centers have in a previous systematic review also shown to be important for several educational and health-related outcomes [111]. School-based health centers might be a powerful tool to reach many children and adolescents at once and have several positive effects, as school is a place where early intervention can be facilitated [37].

In this review, only studies on school-related determinants were found at the organizational level. However, the organizational level also includes sports clubs or other organizations that are visited by children and adolescents [23]. These should be addressed in future research to get a more complete overview of determinants of mental health care use at the organizational level.

Community level

Region of residence was associated with mental health care utilization [35, 41, 47, 52, 54, 64, 99, 105]. However, the direction of association is not straightforward for this determinant as this highly depends on which regions were compared with each other and which region served as the reference. As seen in this review, it is most likely that not the geographical location of the region itself is associated with mental health care utilization but the characteristics of that specific region. Evidence for a positive association was found for three of these area characteristics; a high area-level socio-economic status [35, 55, 57, 71, 76], high accessibility of health services [35, 38, 78, 88, 92] and an urban area [38, 44, 47, 50, 52, 64, 71, 77, 84, 85, 92, 100, 101]. These area characteristics might explain the association with the region of residence. In addition, the community level is a complex level where different factors can interfere with each other [112]. For example, living in an urban area is associated with higher accessibility of care, which can lead to higher care utilization [113]. Furthermore, the association between area-level socio-economic status and mental health care use can be dependent on the number of psychiatrists in the area [53, 114].

Although the evidence was limited, no association was found between area population characteristics and mental health care use, such as the racial/ethnic composition of the area [53, 57] and county child population (i.e., the number of children in an area) [65]. The role of ethnicity in predicting mental health care utilization might primarily be at the individual level rather than at the overall community level [57, 65].

Public policy level

Determinants at the policy level such as parity laws and type of healthcare financing are mainly studied in the U.S.A., where there is no universal health coverage [115]. The most common insurance is private insurance, whereas public insurance is only for disadvantaged groups. There is also a group that is uninsured. In Europe, Canada and Australia, mental health care is covered by a national public health insurance program funded by taxes or government levies [115, 116]. This might explain why determinants at the policy level are less studied in these countries.

In this review, there was evidence of a positive association between parity laws and mental health care utilization [42, 79, 91, 98, 104]. Mental health parity requires insurance coverage for mental health conditions, including substance abuse disorder treatment to be equal to coverage for any other medical condition. A systematic review of policy levers reported that mental health parity increased access to children’s mental health services, by improved affordability [21]. Health insurance expansion also relates to improved affordability, for which evidence for a positive association was found in this review [49, 86, 93, 95].

Evidence for a positive association was also found in this review for the type of care financing (fee-for-service plan compared to a managed care plan). Under the fee-for-service model, health care providers receive payment for every delivered service, while under managed care the state pays a fixed amount per enrollee. The latter encourages more cost-effective service provision. In this review, children in a fee-for-service program were more likely to utilize mental health care compared to children in a managed care program [44, 52, 80]. However, such an association was not found in a study of children using welfare services who also have more extensive needs for mental health services [88].

Collaboration between mental health care providers was positively associated with mental health care utilization. One study found that the linkage between child welfare and mental health services led towards more care for children with the highest needs, but less mental health care in general [65]. Yet, the other studies showed that more collaboration and integrated care services led to more care utilization among children and adolescents with mental health problems.

The recognition of mental health problems is the first step in the decision to utilize mental health care [117]. Screening for mental health problems can facilitate this recognition and help professionals to refer children in need for care [118, 119]. Implementation of screening programs showed a positive association with mental health care utilization in various settings. The screening programs of the included studies were carried out by primary care providers, in waiting rooms of well-child clinics and at schools. One study did not find an association between screening and care utilization. A possible explanation is that they screened five-year-old children, which might be too young for an effective screening program as many mental health problems develop later in childhood [1].

Macro-environmental level

For the determinants at the environmental level, evidence was limited. The identified determinants were derived from only two studies. A potential determinant at the macro-environmental level that is – in our opinion – missing in the current literature is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health care use. The restrictions related to the pandemic have been studied at the policy level [39, 102], but not the effect of the pandemic itself.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this was the first systematic review to investigate a broad range of contextual determinants associated with mental health care utilization in children and adolescents. In this review, a modified version of McLeroy’s ecological model was used to categorize the identified determinants, covering all contextual levels beyond the individual and interpersonal level [23]. Using another model might have led to a different grouping of the determinants. Nevertheless, placing a determinant within a certain level does not influence the level of evidence of that determinant. No restrictions were made on the type of study population or specific age groups, which increases the likelihood that all relevant studies on this topic were included. Furthermore, the search for this review was created by an experienced information specialist who has a PhD degree on literature retrieval in systematic reviews.

Nevertheless, some limitations of this review should also be acknowledged. First, a wide variety of mental health services and populations was included. Research suggests that determinants that are associated with service use may vary across types, amount of service and populations [22, 120], which might have increased the chance to find no or inconclusive associations in our study. Despite the diversity in services and populations, only studies from Western countries and among children under 21 years were included to increase the comparability among studies. Consequently, relevant articles including non-Western countries and people over 21 years might have been excluded.

Second, to assess the level of evidence, guidance for summarizing evidence across studies of different designs and populations is limited. Therefore, a pragmatic approach was chosen as developed and used by others in previously published research [32,33,34]. Choosing a more strict cut-off level (e.g. 67% instead of 60% of studies finding the same direction of an association) would lead to slightly different results. As can be seen in Table 3 this would lead to a different result for only one of the 10 determinant for which evidence was found, which is accessibility of services (inconsistent evidence instead of evidence for a positive association). Furthermore, the approach used for the assessment of the level of evidence does not allow to account for the quality of the studies. As most of the studies were of high quality this might not present a major problem. In the case of studies with limited quality or not well adjusted for mental health problems, this was clearly mentioned. For summarizing the evidence, determinants were grouped together, although the operationalization of determinants might have differed between studies. However, not grouping determinants together would have led to more determinants with limited evidence. Third, most of the included studies were considered as ‘high quality’. It might be that the cut-off for ‘high quality’ was too liberal as the QualSyst tool considers primarily the presence of certain components rather than the quality of these components. Further, the QualSyst tool might lack sensitivity to distinguish articles that are already of good quality from each other [121]. Yet, this tool has been used in many systematic reviews before and can be used for all types of study designs [28,29,30,31]. Most of the studies at the organizational level were not adjusted for mental health problems. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted with caution as the associations between the determinant and mental health care could be direct, but also indirect through mental health problems. Moreover, most of the studies in this review were conducted in the U.S.A. This decreases the external validity of the findings for countries in Europe and Oceania where the health care system is different [115, 116]. Last, the search strategy was restricted to English literature. Therefore, relevant studies carried out in different languages might have been missed.

Implications and future research

Several implications can be drawn from this review. Determinants in contextual levels were identified, of which some can guide care providers and policy makers to improve the access to and provision of care. At the organizational level, evidence of an association between school-based health centers and mental health care utilization was found, although this should be interpreted with caution as most of the studies were of low quality and did not adjust for mental health problems. Our findings indicate that more research is necessary on school-based health centers and access to mental health services. If these centers are found to be important for access to mental health services, at the community level wider implementation of these centers could be warranted in areas that have lower mental health care use, such as areas with a low socioeconomic status, a low accessibility of services and rural areas. In addition, at the policy level, the implementation of mental health screening programs and expansion of mental health insurance coverage, including the implementation of parity laws are warranted as well as the encouragement of collaborations between organizations providing mental health care to increase mental health care utilization and improve access to care.

Future research is necessary, as for most of the identified determinants in this review limited evidence was available, meaning they were studied in three or less studies. To provide stronger evidence on contextual determinants of mental health care use, more research is needed on the understudied determinants. Especially at the organizational level, the number of studies was low. The only determinant with sufficient evidence was a school-based health center, which probably are typical for the U.S.A. Other forms of health service provision at schools that might be more common in countries outside the U.S.A. and their role in improving accessibility to mental health services for youth need further study. Moreover, at this organizational level, only school-related factors were studied, whereas other organizations, such as sports clubs or childcare/kindergarten facilities, can also play important roles in children’s access to care. Also, on the other contextual levels, studies on characteristics of care providers are lacking. Several examples are suggested by Stiffman et al. [109, 122], such as the level of training of the mental health professional, provider behavior, structure or culture of the organization providing care and collaboration between gateway providers. Because of the diversity in the measurement of determinants and mental health care use and a low number of studies on many determinants meta-analyses were not possible for this review. However, future studies should include meta-analyses on well-defined determinants.

Future research should also focus on an understudied age group, which is (early) childhood. Most of the included studies in this review were performed among adolescents. Another direction for future research is to focus on disentangling the mechanisms behind the association we found evidence for. For example, fee-for-service plans led to more care use as compared to managed care. It is important to understand the mechanism behind this association and whether this difference in financing system impacts the quality of care. Last, it is recommended to always adjust for mental health problems when studying mental health care use. In that way, the distinction can be made between determinants that are directly or indirectly related to mental health care use.

Conclusion

This review identified ten contextual determinants that are positively associated with children’s and adolescents’ mental health care utilization; having access to a school-based health center, region of residence, living in an urban area, an area with a high accessibility of mental health care, an area with a high socio-economic status, implementing a mental health parity law, a mental health screening program, collaboration between organizations providing care, a fee-for-service plan (compared to a managed care plan) and extension of health insurance. Policymakers and care providers should be aware that contextual factors play a role in mental health care use by youth. Our findings indicate that addressing contextual factors is possible on organizational, community and public policy levels to improve access to and provision of care.

References

Solmi M, Radua J, Olivola M, Croce E, Soardo L, Salazar de Pablo G, Il Shin J, Kirkbride JB, Jones P, Kim JH, Kim JY, Carvalho AF, Seeman MV, Correll CU, Fusar-Poli P (2021) Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01161-7

Barican JL, Yung D, Schwartz C, Zheng Y, Georgiades K, Waddell C (2022) Prevalence of childhood mental disorders in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis to inform policymaking. Evid Based Ment Health 25:36–44

Dey M, Landolt MA, Mohler-Kuo M (2012) Health-related quality of life among children with mental disorders: a systematic review. Qual Life Res 21:1797–1814

Schulte-Körne G (2016) Mental health problems in a school setting in children and adolescents. Dtsch Arztebl Int 113:183

Sagatun Å, Heyerdahl S, Wentzel-Larsen T, Lien L (2014) Mental health problems in the 10th grade and non-completion of upper secondary school: the mediating role of grades in a population-based longitudinal study. BMC Public Health 14:1–13

Hjorth CF, Bilgrav L, Frandsen LS, Overgaard C, Torp-Pedersen C, Nielsen B, Boggild H (2016) Mental health and school dropout across educational levels and genders: a 4.8-year follow-up study. BMC Public Health 16:976

Mulraney M, Coghill D, Bishop C, Mehmed Y, Sciberras E, Sawyer M, Efron D, Hiscock H (2021) A systematic review of the persistence of childhood mental health problems into adulthood. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 129:182–205

Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony JC, De Graaf RON, Demyttenaere K, Gasquet I, De Girolamo G, Gluzman S, Gureje OYE, Haro JM (2007) Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the world health organization’s world mental health survey initiative. World Psychiatry 6:168

Veldman K, Reijneveld SA, Ortiz JA, Verhulst FC, Bültmann U (2015) Mental health trajectories from childhood to young adulthood affect the educational and employment status of young adults: results from the TRAILS study. J Epidemiol Community Health 69:588–593

Kessler RC, Heeringa S, Lakoma MD, Petukhova M, Rupp AE, Schoenbaum M, Wang PS, Zaslavsky AM (2008) Individual and societal effects of mental disorders on earnings in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Am J Psychiatry 165:703–711

Knapp M (2003) Hidden costs of mental illness. Br J Psychiatry 183:477–478

Scott S, Knapp M, Henderson J, Maughan B (2001) Financial cost of social exclusion: follow up study of antisocial children into adulthood. BMJ 323:191

Angold A, Costello EJ, Burns BJ, Erkanli A, Farmer EMZ (2000) Effectiveness of nonresidential specialty mental health services for children and adolescents in the “real world.” J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 39:154–160

Sanchez AL, Cornacchio D, Poznanski B, Golik AM, Chou T, Comer JS (2018) The effectiveness of school-based mental health services for elementary-aged children: a meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 57:153–165

Conley CS, Shapiro JB, Kirsch AC, Durlak JA (2017) A meta-analysis of indicated mental health prevention programs for at-risk higher education students. J Couns Psychol 64:121

Rapee RM (2013) The preventative effects of a brief, early intervention for preschool-aged children at risk for internalising: follow-up into middle adolescence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 54:780–788

Andersen RM, Davidson PL (2007) Improving access to care in America: individual and contextual indicators. Changing the US health care system: key issues in health services policy and management, 3rd edn. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA, US, pp 3–31

Elster A, Jarosik J, VanGeest J, Fleming M (2003) Racial and ethnic disparities in health care for adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 157:867–874

Ryan SM, Jorm AF, Toumbourou JW, Lubman DI (2015) Parent and family factors associated with service use by young people with mental health problems: a systematic review. Early Interv Psychiatry 9:433–446

Werlen L, Gjukaj D, Mohler-Kuo M, Puhan MA (2019) Interventions to improve children’s access to mental health care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 29:e58

So M, McCord RF, Kaminski JW (2019) Policy levers to promote access to and utilization of children’s mental health services: a systematic review. Adm Policy Ment Health 46:334–351

Eijgermans DGM, Fang Y, Jansen D, Bramer WM, Raat H, Jansen W (2021) Individual and contextual determinants of children’s and adolescents’ mental health care use: a systematic review. Child Youth Serv Rev 131:106288

McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K (1988) An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q 15:351–377

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71

Bramer WM, Giustini D, de Jonge GB, Holland L, Bekhuis T (2016) De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc: JMLA 104:240–243

Wang PS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Bruffaerts R, de Girolamo G, de Graaf R, Gureje O, Haro JM, Karam EG, Kessler RC, Kovess V, Lane MC, Lee S, Levinson D, Ono Y, Petukhova M, Posada-Villa J, Seedat S, Wells JE (2007) Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. The Lancet 370:841–850

Landis JR, Koch GG (1977) The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33:159–174

Kmet LM, Cook LS, Lee RC (2004) Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research

Radez J, Reardon T, Creswell C, Lawrence PJ, Evdoka-Burton G, Waite P (2021) Why do children and adolescents (not) seek and access professional help for their mental health problems? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 30:183–211

Reardon T, Harvey K, Baranowska M, O’Brien D, Smith L, Creswell C (2017) What do parents perceive are the barriers and facilitators to accessing psychological treatment for mental health problems in children and adolescents? A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 26:623–647

Sivaramakrishnan H, Gucciardi DF, McDonald MD, Quested E, Thogersen-Ntoumani C, Cheval B, Ntoumanis N (2021) Psychosocial outcomes of sport participation for middle-aged and older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2021.2004611

Franse CB, Wang L, Constant F, Fries LR, Raat H (2019) Factors associated with water consumption among children: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 16:64

Mazarello Paes V, Hesketh K, O’Malley C, Moore H, Summerbell C, Griffin S, van Sluijs EM, Ong KK, Lakshman R (2015) Determinants of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in young children: a systematic review. Obes Rev 16:903–913

Sallis JF, Prochaska JJ, Taylor WC (2000) A review of correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc 32:963–975

Abbas S, Ihle P, Adler JB, Engel S, Günster C, Holtmann M, Kortevoss A, Linder R, Maier W, Lehmkuhl G, Schubert I (2017) Predictors of non-drug psychiatric/psychotherapeutic treatment in children and adolescents with mental or behavioural disorders. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 26:433–444

Atkins MS, Shernoff ES, Frazier SL, Schoenwald SK, Cappella E, Marinez-Lora A, Mehta TG, Lakind D, Cua G, Bhaumik R, Bhaumik D (2015) Redesigning community mental health services for urban children: supporting schooling to promote mental health. J Consult Clin Psychol 83:839–852

Azrin ST, Huskamp HA, Azzone V, Goldman HH, Frank RG, Burnam MA, Normand SL, Ridgely MS, Young AS, Barry CL, Busch AB, Moran G (2007) Impact of full mental health and substance abuse parity for children in the federal employees health benefits program. Pediatrics 119:e452-459

Bai Y, Wells R, Hillemeier MM (2009) Coordination between child welfare agencies and mental health service providers, children’s service use, and outcomes. Child Abuse Negl 33:372–381

Bakolis I, Stewart R, Baldwin D, Beenstock J, Bibby P, Broadbent M, Cardinal R, Chen S, Chinnasamy K, Cipriani A, Douglas S, Horner P, Jackson CA, John A, Joyce DW, Lee SC, Lewis J, McIntosh A, Nixon N, Osborn D, Phiri P, Rathod S, Smith T, Sokal R, Waller R, Landau S (2021) Changes in daily mental health service use and mortality at the commencement and lifting of COVID-19 “lockdown” policy in 10 UK sites: a regression discontinuity in time design. BMJ Open. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049721

Barry CL, Busch SH (2008) Caring for children with mental disorders: do state parity laws increase access to treatment? J Mental Health Policy Econ 11:57–66

Bird HR, Shrout PE, Duarte CS, Shen SA, Bauermeister JJ, Canino G (2008) Longitudinal mental health service and medication use for ADHD among Puerto Rican youth in two contexts. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatr 47:879–889

Block EP, Xu H, Azocar F, Ettner SL (2020) The mental health parity and addiction equity act evaluation study: child and adolescent behavioral health service expenditures and utilization. Health Econ 29:1533–1548

Booth RG, Allen BN, Bray Jenkyn KM, Li L, Shariff SZ (2018) Youth mental health services utilization rates after a large-scale social media campaign: population-based interrupted time-series analysis. JMIR Ment Health 5:e27

Brannan AM, Heflinger CA (2005) Child behavioral health service use and caregiver strain: comparison of managed care and fee-for-service medicaid systems. Ment Health Serv Res 7:197–211

Britto MT, Klostermann BK, Bonny AE, Altum SA, Hornung RW (2001) Impact of a school-based intervention on access to healthcare for underserved youth. J Adolesc Health 29:116–124

Brown RP, Imura M, Mayeux L (2014) Honor and the stigma of mental healthcare. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 40:1119–1131

Bryson SA, Akin BA (2015) Predictors of admission to acute inpatient psychiatric care among children enrolled in medicaid. Adm Policy Ment Health 42:197–208

Chisolm DJ, Klima J, Gardner W, Kelleher KJ (2009) Adolescent behavioral risk screening and use of health services. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res 36:374–380

Cidav Z, Marcus SC, Mandell DS (2014) Home- and community-based waivers for children with autism: effects on service use and costs. Intellect Dev Disabil 52:239–248

Cohen P, Hesselbart CS (1993) Demographic factors in the use of children’s mental health services. Am J Public Health 83:49–52

Cole MB, Qin Q, Sheldrick RC, Morley DS, Bair-Merritt MH (2019) The effects of integrating behavioral health into primary care for low-income children. Health Serv Res 54:1203–1213

Cook JA, Heflinger CA, Hoven CW, Kelleher KJ, Mulkern V, Paulson RI, Stein-Seroussi A, Fitzgibbon G, Burke-Miller J, Williams M, Kim JB (2004) A multi-site study of medicaid-funded managed care versus fee-for-service plans’ effects on mental health service utilization of children with severe emotional disturbance. J Behav Health Serv Res 31:384–402

Cummings JR (2014) Contextual socioeconomic status and mental health counseling use among US adolescents with depression. J Youth Adolesc 43:1151–1162

Davila IG, Cramm H, Chen S, Aiken AB, Ouellette B, Manser L, Kurdyak P, Mahar AL (2020) Intra-provincial variation in publicly funded mental health and addictions “services” use among Canadian armed forces families posted across Ontario. Can Stud Popul 47:27–39

Efron D, Gulenc A, Sciberras E, Ukoumunne OC, Hazell P, Anderson V, Silk TJ, Nicholson JM (2019) Prevalence and predictors of medication use in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: evidence from a community-based longitudinal study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 29:50–57

Finnvold JE (2019) How income inequality and immigrant background affect children’s use of mental healthcare services in Oslo. Norway Child Indic Res 12:1881–1896

Fitts JJ, Aber MS, Allen NE (2019) Individual, family, and site predictors of youth receipt of therapy in systems of care. Child Youth Care Forum 48:737–755

Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Alegría M, Costello EJ, Gruber MJ, Hoagwood K, Leaf PJ, Olin S, Sampson NA, Kessler RC (2013) School mental health resources and adolescent mental health service use. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 52:501–510

Grimes KE, Creedon TB, Webster CR, Coffey SM, Hagan GN, Chow CM (2018) Enhanced child psychiatry access and engagement via integrated care: a collaborative practice model with pediatrics. Psychiatr Serv 69:986–992

Hacker K, Penfold R, Arsenault LN, Zhang F, Soumerai SB, Wissow LS (2017) The impact of the Massachusetts behavioral health child screening policy on service utilization. Psychiatr Serv 68:25–32

Hacker KA, Penfold RB, Arsenault LN, Zhang F, Soumerai SB, Wissow LS (2015) Effect of pediatric behavioral health screening and colocated services on ambulatory and inpatient utilization. Psychiatr Serv 66:1141–1147

Halladay J, Bennett K, Weist M, Boyle M, Manion I, Campo M, Georgiades K (2020) Teacher-student relationships and mental health help seeking behaviors among elementary and secondary students in Ontario Canada. J Sch Psychol 81:1–10

Hamersma S, Ye J (2021) The effect of public health insurance expansions on the mental and behavioral health of girls and boys. Soc Sci Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113998

Howell E, McFeeters J (2008) Children’s mental health care: differences by race/ethnicity in urban/rural areas. J Health Care Poor Underserved 19:237–247

Hurlburt MS, Leslie LK, Landsverk J, Barth RP, Burns BJ, Gibbons RD, Slymen DJ, Zhang J (2004) Contextual predictors of mental health service use among children open to child welfare. Arch Gen Psychiatry 61:1217–1224

Husky MM, Kaplan A, McGuire L, Flynn L, Chrostowski C, Olfson M (2011) Identifying adolescents at risk through voluntary school-based mental health screening. J Adolesc 34:505–511

Hussaini KS, Offutt-Powell T, James G, Koumans EH (2021) Assessing the effect of school-based health centers on achievement of national performance measures. J Sch Health. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.13060

Hutchinson P, Carton TW, Broussard M, Brown L, Chrestman S (2012) Improving adolescent health through school-based health centers in post-Katrina New Orleans. Child Youth Serv Rev 34:360–368

Ivert AK, Torstensson Levander M, Merlo J (2013) Adolescents’ utilisation of psychiatric care, neighbourhoods and neighbourhood socioeconomic deprivation: a multilevel analysis. PLoS ONE 8:e81127

Janopaul-Naylor E, Morin SL, Mullin B, Lee E, Barrett JG (2019) Promising approaches to police-mental health partnerships to improve service utilization for at-risk youth. Transl Issues Psychol Sci 5:206–215

Johnson SE, Lawrence D, Hafekost J, Saw S, Buckingham WJ, Sawyer M, Ainley J, Zubrick SR (2016) Service use by Australian children for emotional and behavioural problems: findings from the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and Wellbeing. Aust New Zealand J Psychiatry 50:887–898

Joyce NR, Huskamp HA, Hadland SE, Donohue JM, Greenfield SF, Stuart EA, Barry CL (2017) The alternative quality contract: impact on service use and spending for children with ADHD. Psychiatr Serv 68:1210–1212

Kang-Yi CD, Mandell DS, Hadley T (2013) School-based mental health program evaluation: children’s school outcomes and acute mental health service use. J Sch Health 83:463–472

Kaplan DW, Brindis CD, Phibbs SL, Melinkovich P, Naylor K, Ahlstrand K (1999) A comparison study of an elementary school-based health center: effects on health care access and use. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 153:235–243

Kaplan DW, Calonge BN, Guernsey BP, Hanrahan MB (1998) Managed care and school-based health centers: use of health services. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 152:25–33

Kim M, Garcia AR, Yang S, Jung N (2018) Area-socioeconomic disparities in mental health service use among children involved in the child welfare system. Child Abuse Negl 82:59–71

Kodjo CM, Auinger P (2004) Predictors for emotionally distressed adolescents to receive mental health care. J Adolesc Health 35:368–373

Kovess-Masfety V, Van Engelen J, Stone L, Otten R, Carta MG, Bitfoi A, Koc C, Goelitz D, Lesinskiene S, Mihova Z, Fermanian C, Pez O, Husky M (2017) Unmet need for specialty mental health services among children across Europe. Psychiatr Serv 68:789–795

Li X, Ma J (2020) Does mental health parity encourage mental health utilization among children and adolescents? Evidence from the 2008 mental health parity and addiction equity act (MHPAEA). J Behav Health Serv Res 47:38–53

Mandell DS, Boothroyd RA, Stiles PG (2003) Children’s use of mental health services in different medicaid insurance plans. J Behav Health Serv Res 30:228–237

Mann E, Pyevich M, Eyck PT, Scholz T (2021) Impact of shared plans of care on healthcare utilization by children with special healthcare needs and mental health diagnoses. Matern Child Health J 25:584–589

McKay MM, Stoewe J, McCadam K, Gonzales J (1998) Increasing access to child mental health services for urban children and their caregivers. Health Soc Work 23:9–15

Mendenhall AN (2012) Predictors of service utilization among youth diagnosed with mood disorders. J Child Fam Stud 21:603–611

Monz BU, Houghton R, Law K, Loss G (2019) Treatment patterns in children with autism in the United States. Autism Res 12:517–526

Paananen R, Santalahti P, Merikukka M, Rämö A, Wahlbeck K, Gissler M (2013) Socioeconomic and regional aspects in the use of specialized psychiatric care–a Finnish nationwide follow-up study. Eur J Public Health 23:372–377

Patrick C, Padgett DK, Burns BJ, Schlesinger HJ, Cohen J (1993) Use of inpatient services by a national-population - do benefits make a difference. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatr 32:144–152

Quast T, Gregory S, Storch EA (2018) Utilization of mental health services by children displaced by Hurricane Katrina. Psychiatr Serv 69:580–586

Raghavan R, Leibowitz AA, Andersen RM, Zima BT, Schuster MA, Landsverk J (2006) Effects of medicaid managed care policies on mental health service use among a national probability sample of children in the child welfare system. Child Youth Serv Rev 28:1482–1496

Rocks S, Fazel M, Tsiachristas A (2020) Impact of transforming mental health services for young people in England on patient access, resource use and health: a quasi-experimental study. BMJ Open. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034067

Sayal K, Owen V, White K, Merrell C, Tymms P, Taylor E (2010) Impact of early school-based screening and intervention programs for ADHD on children’s outcomes and access to services: Follow-up of a school-based trial at age 10 years. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 164:462–469

Sen BP, Blackburn J, Morrisey MA, Kilgore ML, Menachemi N, Caldwell C, Becker DJ (2018) Impact of mental health parity and addiction equity act on costs and utilization in Alabama’s children’s health insurance program. Acad Pediatr. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2018.07.014

Slade EP (2002) Effects of school-based mental health programs on mental health service use by adolescents at school and in the community. Ment Health Serv Res 4:151–166

Snowden LR, Masland M, Wallace N, Fawley-King K, Cuellar AE (2008) Increasing California children’s medicaid-financed mental health treatment by vigorously implementing medicaid’s early periodic screening, diagnosis, and treatment (EPSDT) program. Med Care 46:558–564

Sobel SN, Anisman S, Hamdy H (1998) Factors affecting emergency service utilization at a rural community mental health center. Commun Ment Health J 34:157–163

Stein BD, Sorbero MJ, Goswami U, Schuster J, Leslie DL (2012) Impact of a private health insurance mandate on public sector autism service use in Pennsylvania. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 51:771–779

Sterling S, Kline-Simon AH, Jones A, Hartman L, Saba K, Weisner C, Parthasarathy S (2019) Health care use over 3 years after adolescent SBIRT. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2803

Stevens J, Klima J, Chisolm D, Kelleher KJ (2009) A trial of telephone services to increase adolescent utilization of health care for psychosocial problems. J Adolesc Health 45:564–570

Stuart EA, McGinty EE, Kalb L, Huskamp HA, Busch SH, Gibson TB, Goldman H, Barry CL (2017) Increased service use among children with autism spectrum disorder associated with mental health parity law. Health Aff 36:337–345

Sturm R, Ringel JS, Andreyeva T (2003) Geographic disparities in children’s mental health care. Pediatrics 112:e308

Sullivan AL, Sadeh S (2015) Psychopharmacological treatment among adolescents with disabilities: prevalence and predictors in a nationally representative sample. Sch Psychol Q 30:443–455

Thomas KC, Ellis AR, McLaurin C, Daniels J, Morrissey JP (2007) Access to care for autism-related services. J Autism Dev Disord 37:1902–1912

Tromans S, Chester V, Harrison H, Pankhania P, Booth H, Chakraborty N (2020) Patterns of use of secondary mental health services before and during COVID-19 lockdown: observational study. BJPsych Open. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.104

van der Linden J, Drukker M, Gunther N, Feron F, van Os J (2003) Children’s mental health service use, neighbourhood socioeconomic deprivation, and social capital. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 38:507–514

Walter AW, Yuan Y, Cabral HJ (2017) Mental health services utilization and expenditures among children enrolled in employer-sponsored health plans. Pediatrics 139:S127–S135

Waxmonsky JG, Baweja R, Liu G, Waschbusch DA, Fogel B, Leslie D, Pelham WE Jr (2019) A commercial insurance claims analysis of correlates of behavioral therapy use among children with ADHD. Psychiatr Serv 70:1116–1122

Williams KA, Chapman MV (2015) Mental health service use among youth with mental health need: do school-based services make a difference for sexual minority youth? School Ment Health 7:120–131

Witt WP, Kasper JD, Riley AW (2003) Mental health services use among school-aged children with disabilities: the role of sociodemographics, functional limitations, family burdens, and care coordination. Health Serv Res 38:1441–1466

Zablotsky B, Maenner MJ, Blumberg SJ (2019) Geographic disparities in treatment for children with autism spectrum disorder. Acad Pediatr 19:740–747

Stiffman AR, Pescosolido B, Cabassa LJ (2004) Building a model to understand youth service access: the gateway provider model. Ment Health Serv Res 6:189–198

Bains RM, Diallo AF (2016) Mental health services in school-based health centers: systematic review. J Sch Nurs 32:8–19

Knopf JA, Finnie RKC, Peng Y, Hahn RA, Truman BI, Vernon-Smiley M, Johnson VC, Johnson RL, Fielding JE, Muntaner C, Hunt PC, Phyllis Jones C, Fullilove MT (2016) School-based health centers to advance health equity: a community guide systematic review. Am J Prev Med 51:114–126

Krabbendam L, van Vugt M, Conus P, Söderström O, Empson LA, van Os J, Fett A-KJ (2021) Understanding urbanicity: how interdisciplinary methods help to unravel the effects of the city on mental health. Psychol Med 51:1099–1110

Murray G, Judd F, Jackson H, Fraser C, Komiti A, Hodgins G, Pattison P, Humphreys J, Robins G (2004) Rurality and mental health: the role of accessibility. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 38:629–634

Annequin M, Weill A, Thomas F, Chaix B (2015) Environmental and individual characteristics associated with depressive disorders and mental health care use. Ann Epidemiol 25:605–612

Ridic G, Gleason S, Ridic O (2012) Comparisons of health care systems in the United States, Germany and Canada. Materia socio-medica 24:112–120

Armstrong BK, Gillespie JA, Leeder SR, Rubin GL, Russell LM (2007) Challenges in health and health care for Australia. Med J Aust 187:485–489

Cauce AM, Domenech-Rodríguez M, Paradise M, Cochran BN, Shea JM, Srebnik D, Baydar N (2002) Cultural and contextual influences in mental health help seeking: a focus on ethnic minority youth. J Consult Clin Psychol 70:44

Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB (2002) Unmet need for mental health care among US children: variation by ethnicity and insurance status. Am J Psychiatry 159:1548–1555

Levitt JM, Saka N, Romanelli LH, Hoagwood K (2007) Early identification of mental health problems in schools: the status of instrumentation. J Sch Psychol 45:163–191

Li W, Dorstyn DS, Denson LA (2016) Predictors of mental health service use by young adults: a systematic review. Psychiatr Serv 67:946–956

Landais LL, Damman OC, Schoonmade LJ, Timmermans DRM, Verhagen EALM, Jelsma JGM (2020) Choice architecture interventions to change physical activity and sedentary behavior: a systematic review of effects on intention, behavior and health outcomes during and after intervention. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 17:1–37

Stiffman AR, Hadley-Ives E, Doré P, Polgar M, Horvath VE, Striley C, Elze D (2000) Youths’ access to mental health services: the role of providers’ training, resource connectivity, and assessment of need. Ment Health Serv Res 2:141–154

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Verhoog, S., Eijgermans, D.G.M., Fang, Y. et al. Contextual determinants associated with children’s and adolescents’ mental health care utilization: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-02077-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-02077-5