Abstract

Reactions between (E)-2-aryl-1-cyano-1-nitroethenes and diazafluorene lead to acyclic 2,3-diazabuta-1,3-diene derivatives, instead of the expected pyrazoline systems. DFT calculations suggest that this is a consequence of formation of zwitterionic structure in the first stage of the reaction. It must be noted that this is a specific property of the (E)-2-aryl-1-cyano-1-nitroethenes group, in contrast to most other conjugated nitroalkenes.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Conjugated nitroalkenes (CNA) are very useful and universal synthons in organic synthesis. On their basis, many valuable compounds may be prepared, such as nitronic acid esters [1], amines [2], oximes [3] and others [2]. Additionally, the presence of a highly electron-withdrawing nitro group stimulates π-deficiency of a double bond, which activates these compounds in a stereo-controlled reaction with nucleophilic reagents such as dienes [2, 4, 5], 1,3-dipoles [3, 6] and acetylenes [4].

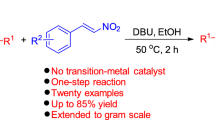

(E)-2-Phenyl-1-cyano-1-nitroethene and their aryl-substituted analogs (ACNE) were prepared for the first time in the first half of the twentieth century [7]. At present, several compounds from this group are known [8–11]. However, their chemical properties are not well known. Some compounds have been described very recently. In particular, some examples of participation of ACNE in Diels–Alder reactions as dienophiles [12–15] as well as heterodienes [8, 16, 17] are explored. Additionally, some examples of catalyzed 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions between ACNE and trimethylsilyl azide are also analyzed [18, 19]. Unfortunately, this method does not yield stable adducts, because the primary reaction products decompose partially under reaction conditions. Actually, any examples of thermal (non-catalyzed) 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions involving ACNE are unknown. This work is an attempt to fill this gap and is a continuation of our systematic study about participation of CNA in cycloaddition reactions [15, 20–24]. In particular, we have decided to shed light on the reactions between the homogenous series of ACNE (1a–1d) and diazafluorene (2), as a model allenyl-type 1,3-dipole with >(C−)–(N+)≡N functional group. Theoretically, these reactions should give attractive, from a practical point of view, nitrofunctionalized pyrazoline systems (Scheme 1). In addition to experimental studies, we also performed comprehensive quantum chemical studies to understand better the nature and molecular mechanism of these reactions.

Results and discussion

Firstly, we prepared the reaction components. For this purpose, we applied methodologies described earlier (see the experimental section). Next, the analysis of the interaction between the addends in the expected cycloaddition course was performed. Global and local electronic properties of (E)-2-aryl-1-cyano-1-nitroethenes had been analyzed in detail previously [17, 25]. It was discovered that all these compounds were characterized by a high global electrophilicity (in the case of compounds 1a–1d and were in the range of 3.14−3.68eV). In comparison (Table 1), diazafluorene has evidently weaker electrophilic nature (ω = 1.84 eV). Additionally, 2 is characterized by a relatively high global nucleophilcity (more than 3.5 eV). In consequence, the interaction between CNA 1a–1d and 2 may be considered a polar one [26]. Subsequently, the local electronic properties of addends have been analyzed. As established earlier, in all CNA 1a–1d, most of the electrophilic center is located at the β-position of the nitrovinyl moiety [17, 25]. On the other hand, most of the nucleophilic center in the >CNN moiety of 2 is located on the terminal nitrogen atom. In polar cycloadditions, a reaction course is controlled by the nature of the local nucleophile–electrophile interaction. Therefore, we have assumed that the reaction channel A should be preferred.

To verify the quantum chemical simulations, we performed experimental tests of the reactions of interest. In the first step, we explored reactions involving ACNE 1a. It was found that this reaction proceeds in MeNO2 solution under mild conditions and yields a dark brown solid. HPLC analysis of the post-reaction mixture shows the existence of one reaction product, which was isolated by crystallization from ethanol. Its constitution was established by means of elemental analysis as well as spectral techniques. It was found unexpectedly that the results of the elemental analysis were fundamentally different from those of the expected adduct. Next, in the IR spectrum, any bands from NO2 as well as CN groups were not observed. On the other hand, the MS spectrum gives a molecular ion, which suggests that the molecular weight is less than that in the expected adduct. This suggest the absence of the C(CN)NO2 moiety in the molecule. Thus, we established that it is not a five-membered heterocyclic product, but a 2,3-diazabuta-1,3-diene derivative 5a. This was fully confirmed by the single crystal X-ray structure determination (Fig. 1 as well as Supplementary Material). For a full characteristic of this compound, 1H and 13C NMR spectra were also recorded (see “Experimental” section).

Similarly, we analyzed the reactions involving ACNE 1a–1d. In all cases, respectively, 2,3-diazabuta-1,3-diene derivatives 5b–5d were isolated instead of the expected nitropyrazolines. Next, we tested the reactions between diazafluorene 2 and used ACNE in other, different solvents such as acetonitrile, DCM and chlorobenzene. In all cases, only 2,3-diazabuta-1,3-diene derivatives were isolated, without any cycloadducts.

This phenomenon can be explained when assuming that the primary reaction product 3a–3d spontaneously decomposed with: C(CN)NO2 carbene elimination according to the retro-[4 + 1]-cycloaddition scheme (path C on Scheme 2). Theoretically, the highly substituted five-member heterocycles may have decomposed with the ring opening via carbene elimination. It should be highlighted, however, that any cases of this type of decomposition of nitropyrazoline systems had not been previously described. Some of these heterocycles decomposed under mild conditions, but via completely different mechanisms [28–32]. Alternatively, it may be assumed that in the first reaction stage, a zwitterionic intermediate I is formed. The zwitterionic structure of I is probably stabilized by a push–pull electronic effect, which is determined by the presence of two EWG groups (NO2 and CN) in the terminal position. A similar effect has been recently explored [11] in detail in the case of a molecule, which has similar structural moieties. In the next step, it is converted via C(CN)NO2 carbene elimination into a 2,3-diazabuta-1,3-diene derivative (Scheme 2). It should be noted at this point that the possibility of the existence of zwitterionic structures on the paths of reactions involving CNA has been recently described in the case of interactions between diarylnitrones and 1-EWG-substituted 1-nitroethenes [33, 34] as well as between thiocarbonylylides and nitroethene [35, 36].

To confirm this hypothesis, we have performed DFT simulation of theoretically possible paths for a model reaction involving CNA 1c. It was found that, in contrast to the reaction 1c + 2 → I, both cycloadditions leading finally to pyrazoline systems (3c and 4c) should be treated as forbidden from a kinetic point of view. In particular, for reactions 1c + 2 → 3c(4c), Gibbs free energy of activation is higher than 141 kJ/mol, whereas in reaction 1c + 2 → I about 128 kJ/mol. In consequence, our calculations may support mechanism via paths D + E, which is illustrated in Scheme 2. The key physical parameters of all considered transition states are presented in Fig. 2. It should be noted that the zwitterionic nature of I, as well as the charge distribution on its molecule, was confirmed by a population Mulliken analysis (see the GEDT value).

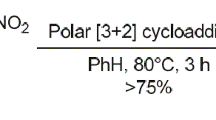

Finally, it should be noted that the described reaction course is a specific property of the ACNE group. In comparison, a similar reaction between (E)-3,3,3-trichloro-1-nitroprop-1-ene (6) (which has similar electrophilicity to ACNE [22]) and diazafluorene proceeds in MeNO2 solution under mild conditions and gives pyrazoline 7 with quantitative yield (Scheme 3). Interestingly, this adduct is easily decomposed into 8 under relatively mild conditions. This decomposition proceeded via the HCl elimination stage.

Conclusion

Reactions between allenyl-type 1,3 dipoles and ethylene/acetylene derivatives proceed generally according to the cycloaddition scheme [27–39]. Unexpectedly, diazafluorene reacts with (E)-2-aryl-1-cyano-1-nitroethenes via another mechanism. In particular, in these processes, acyclic 2,3-diazabuta-1,3-diene derivatives are formed instead of heterocyclic adducts. Probably, this is a consequence of the formation of the zwitterionic structure in the first reaction stage. This hypothesis is supported by DFT calculations. It must be noted that there is a specific property of the (E)-2-aryl-1-cyano-1-nitroethenes group, in contrast to most other conjugated nitroalkenes. We found that a similar reaction between (E)-3,3,3-trichloro-1-nitroprop-1-ene and diazafluorene proceeds under mild conditions and gives 4-nitropyrazoline as the product.

Experimental

The melting points were determined on a Boetius apparatus and are uncorrected. Elemental analyses were performed on a Perkin-Elmer PE-2400 CHN apparatus. IR spectra were recorded on a Bio-Rad spectrophotometer in CCl4 solution. The 1H NMR (500 MHz) and 13C NMR (125 MHz) spectra were recorded on a Bruker AMX 500 spectrometer. Liquid chromatography (HPLC) was done using a Knauer apparatus equipped with a UV/Vis detector. For monitoring of the reaction progress, LiChrospher 18-RP 5 μm column (4 × 240 mm) and 75% methanol as the eluent at a flow rate of 1.0 cm3/min were used.

Nitroalkenes 1a–1d [9, 11] and 6 [46] and diazafluorene (2) [45] were synthesized according to the procedures described earlier.

X-ray crystal structure determination

The X-ray diffraction intensities for 5a were collected at 120 K on SuperNova X-ray diffractometer equipped with Atlas S2 CCD detector using the mirror-monochromatized CuKα radiation (λ = 1.54184 Å). All data were collected using the ω scan technique, with an angular scan width of 1.0°. The programs CrysAlis CCD, CrysAlis Red and CrysAlisPro [40, 41] were used for data collection, cell refinement and data reduction. The structures were solved by direct methods using SHELXS-97 and refined by the full-matrix least squares on F 2 using the SHELXL-97 [42]. The H atoms were positioned geometrically and allowed to ride on their parent atoms, with U iso(H) = 1.2 U eq(C). The molecular plot was drawn with Olex2 [43]. Compound 5a crystallizes in an orthorhombic Pna21 space group. The molecule is nearly planar. The two aromatic parts of the molecule are twisted around the central linear fragment by ca. 14.6(9)°. The bond lengths in the linear fragment were as follows: C1 = N1 1.302(6) Å, N1–N2 1.392(6) Å, N2 = C14 1.298(6) Å, and C14–C15 1.442(7) Å, showing some degree of electron delocalization along this molecular fragment in comparison to another related structure of p-methoxybenzaldehyde 9-fluorenylidenehydrazone with the respective bond lengths: C8 = N2 1.286 (4) Å, N1–N2 1.418 (3) Å, N1 = C7 1. 264 (4) Å, and C7–C6 1.453 (4) Å (atom labels as in the original paper) [44].

The experimental details and final atomic parameters for 5a have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre as supplementary material (CCDC ID 1448932). Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge on request via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/conts/retrieving.html (or from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12, Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 1223 336033).

Reactions between CNA and diazafluorene: general procedure

A mixture of appropriate nitroalkene (1a–1d or 6, 0.012 mol) and diazafluorene (0.010 mol) in 5 cm3 of the appropriate solvent was stirred at room temperature for 12 h. The solvent was evaporated in vacuo to dryness and the semisolid residue was recrystallized firstly from ethanol and then from cyclohexane.

1-(4-Chlorophenyl)-2,3-diaza-4-(9-fluorenylidene)buta-1,3-diene (5a, C20H13ClN2)

Yield: 95%; t R = 10.6 min; yellow crystals; m.p.: 103–105 °C; IR (KBr): \(\bar{\nu }\) = 2160, 1954, 1539, 1083 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 8.54 (s, 1H, CH), 7.92 (d, 1H, J = 7.6 Hz, CHAr), 7.88 (d, 2H, J = 8.5 Hz, CHAr), 7.68–7.62 (m, 2H, CHAr), 7.52–7.43 (m, 5H, CHAr), 7.35–7.31 (m, 2H, CHAr) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 158.2, 142.5, 137.3, 132.9, 131.6, 131.3, 131.0, 130.6, 129.8, 129.3, 128.3, 128.2, 123.0, 122.9, 120.1, 120.0, 119.9 ppm; MS: m/z = 316 (M+), 205; UV–Vis (methanol): λ max = 342, 260, 196 nm.

1-(4-Fluorophenyl)-2,3-diaza-4-(9-fluorenylidene)buta-1,3-diene (5b, C20H13FN2)

Yield: 93%; t R = 9.5 min; yellow crystals; m.p.: 99–101 °C; IR (KBr): \(\bar{\nu }\) = 2160, 1957, 1549, 1103 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 8.56 (s, 1H, CH), 7.96 (dd, 2H, J = 5.5 Hz, 8.7 Hz, CHAr), 7.92 (d, 1H, J = 7.6 Hz, CHAr), 7.66–7.62 (m, 2H, CHAr), 7.46–7.43 (m, 3H, CHAr), 7.33 (q, 2H, J = 8.7 Hz, CHAr), 7.22 (t, 2H, J = 8.5 Hz, CHAr) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 158.5, 142.1 (d, J C–F = 114.4 Hz), 136.8, 131.7, 131.5, 131.2, 130.7, 130.6, 130.5, 130.3, 128.2, 122.9, 120.0, 119.9, 116.3, 116.1, 116.0 ppm; MS: m/z = 300 (M+), 205; UV–Vis (methanol): λ max = 338, 259, 201 nm.

1-Phenyl-2,3-diaza-4-(9-fluorenylidene)buta-1,3-diene (5c, C20H14N2)

Yield: 95%; t R = 8.5 min; orange crystals; m.p.: 83–84 °C; IR (KBr): \(\bar{\nu }\) = 2161, 1955, 1543, 1099 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 8.59 (s, 1H, CH), 8.49 (d, 1H, J = 7.5 Hz, CHAr), 7.97–7.93 (m, 3H, CHAr), 7.66–7.62 (m, 2H, CHAr), 7.54–7.52 (m, 3H, CHAr), 7.46–7.42 (m, 2H, CHAr), 7.36–7.31 (m, 2H, CHAr) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 160.4, 159.6, 142.5, 136.9, 134.4, 131.7, 131.5, 131.2, 130.7, 129.0, 128.7, 128.1, 127.9, 127.7, 125.5, 122.9, 120.8, 119.9 ppm; MS: m/z = 282 (M+), 205; UV–Vis (methanol): λ max = 338, 255, 208 nm.

1-(4-Methoxylphenyl)-2,3-diaza-4-(9-fluorenylidene)buta-1,3-diene (5d, C21H16N2O)

Yield: 95%; t R = 9.2 min; yellow crystals; m.p.: 127–130 °C; IR (KBr): \(\bar{\nu }\) = 2160, 2038, 1599, 1099 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 8.58 (s, 1H, CH), 8.57 (d, 1H, J = 7.8 Hz, CHAr), 7.94 (d, 1H, J = 9.5 Hz, CHAr), 7.91 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz, CHAr), 7.65 (dd, 2H, J = 8.2 Hz, 5.2 Hz, CHAr), 7.43 (t, 2H, J = 6.7 Hz, CHAr), 7.35–7.31 (m, 2H, CHAr), 7.05–7.03 (m, 2H, CHAr), 3.90 (s, 3H, CH3) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 162.3, 160.3, 160.0, 142.4, 137.0, 131.8, 131.3, 131.0, 130.8, 130.7, 130.5, 128.2, 128.1, 127.3, 122.8, 119.9, 119.8, 114.5, 55.5 ppm; MS: m/z = 312 (M+), 205; UV–Vis (methanol): λ max = 358, 225, 197 nm.

4′,5′-Dihydro-4′-nitro-5′-(trichloromethyl)spiro[9H-fluorene-9,3′-[3H]pyrazole] (7, C16H10Cl3N3O2)

Yield: 93%; t R = 14.8 min; white crystals; m.p.: 138–140 °C; IR (KBr): \(\bar{\nu }\) = 2993, 2950, 1557, 1359, 748 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.83 (d, 1H, J = 8.5 Hz, CHAr), 7.79 (d, 1H, J = 6.9 Hz, CHAr), 7.61–7.58 (m, 1H, CHAr), 7.52 (t, 1H, J = 7.6 Hz, CHAr), 7.46–7.42 (m, 2H, CHAr), 7.33–7.29 (m, 1H, CHAr), 7.03 (d, 1H, J = 7.0 Hz, CHAr), 6.82 (d, 1H, J = 7.6 Hz, CHAr), 5.70 (d, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz, CHAr) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 142.0, 134.7, 131.5, 131.1, 129.0, 128.4, 125.2, 124.1, 121.0, 120.9, 104.5, 103.8, 94.8, 88.6 ppm.

4′,5′-Dihydro-4′-nitro-5′-(dichloromethylene)spiro[9H-fluorene-9,3′-[3H]pyrazole] (8, C16H9Cl2N3O2)

Yield: 96%; white crystals; m.p.: 175–177.5 °C; IR (KBr): \(\bar{\nu }\) = 3014, 2975, 2910, 1629, 1560, 1353, 742 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.83–7.81 (m, 2H, CHAr), 7.58–7.52 (m, 2H, CHAr), 7.36–7.31 (m, 2H, CHAr), 7.11 (d, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz, CHAr), 6.86 (d, 1H, J = 8.6 Hz, CHAr), 5.73 (s, 1H, CHAr) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 142.2, 140.5 136.4, 134.5, 131.3, 131.0, 129.0, 128.8, 124.9, 122.6, 121.1, 120.9, 101.2, 87.9 ppm; MS: m/z = 345 (M+).

Quantum chemical calculations

All calculations reported in this paper were performed on “Zeus” supercomputer in the “Cyfronet” computational center in Cracow. Global and local electronic properties were estimated on the basis of structures obtained—according to Domingo suggestions [47, 48]—on the basis of B3LYP/6-31G(d) calculations. For this purpose, we have used structures created by the standard procedure [49]. In particular, the electronic chemical potentials (μ) and chemical hardness (η) were evaluated in terms of one-electron energies of FMO (E HOMO and E LUMO) using the equations:

Next, the values of μ and η were then used for the calculation of global electrophilicity (ω) [47, 48] according to the formula:

and the global nucleophilicity (N) [50] can be expressed in terms of the equation:

The local nucleophilicity (N k ) [51] condensed to atom k was calculated using global nucleophilicity N and Parr function P −k [52] according to the formula:

For the simulation of the reaction paths, hybrid functional B3LYP with the 6-31 ++G(d), basis set included in the GAUSSIAN 09 package [53] was used. It was found previously that calculations using B3LYP functional illustrate well the structure of transition states in polar 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions involving conjugated nitroalkenes [22, 23, 30]. The critical points on the reaction paths were localized in an analogous manner as in the case of the previously analyzed cycloadditions of diaryldiazomethanes with nitroacetylene [54]. In particular, for structure optimization of the reactants and the reaction products, the Berny algorithm was applied. First-order saddle points were localized using the QST2 procedure. The transition states were verified by diagonalization of the Hessian matrix and by an analysis of the intrinsic reaction coordinates (IRC).

All calculations were carried out for the simulated presence of nitromethane as the reaction medium. For this purpose, PCM [55] was used. For optimized structures, the thermochemical data for the temperature T = 298 K and pressure p = 1 atm were computed using vibrational analysis data. Global electron density transfer (GEDT) [56] was calculated according to the formula:

where q A is the net Mulliken charge and the sum is taken over all the atoms of the dipolarophile. Indexes of σ-bonds development (l) were calculated according to the formula [30]:

where r TS A–B is the distance between the reaction centers A and B at the TS and r P A–B is the same distance at the corresponding product.

References

Belenkii LI (2007) Nitrile Oxides. In: Feuer H (ed) Nitrile oxides, nitrones, and nitronates in organic synthesis. Wiley, New Jersey, p 1

Ono N (2001) The nitro group in organic synthesis. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim

Perekalin VV, Lipina ES, Berestovitskaya VM, Efremov DA (1994) Nitroalkenes: conjugated nitro compounds. Wiley, Chichester

Halimehjani AZ, Namboothiri INN, Hooshmand SE (2014) RSC Adv 4:31261

Dresler E, Jasińska E, Łapczuk-Krygier A, Kącka A, Nowakowska Bogdan E, Jasiński R (2015) Chemik 69:645

Jasiński R (2015) Reakcje 1,3-dipolarnej cykloaddycji: aspekty mechanistyczne i zastosowanie w syntezie organicznej. RTN, Radom

Ried W, Köhler E (1956) Liebbigs Ann Chem 598:144

Amantini D, Fringuelli F, Piermatti O, Pizzo F, Vaccaro L (2001) Green Chem 3:229

Boguszewska-Czubara A, Łapczuk-Krygier A, Rykała K, Biernasiuk A, Wnorowski A, Popiołek Ł, Maziarka A, Hordyjewska A, Jasiński R (2015) J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 31:900

Valizadeh H, Mamaghani M, Badrian A (2005) Synth Commun 35:785

Jasiński R, Mirosław B, Demchuk OM, Babyuk D, Łapczuk-Krygier A (2016) J Mol Struct 1108:689

Łapczuk-Krygier A, Ponikiewski P, Jasiński R (2014) Crystallogr Rep 59:961

Baichurin RI, Aboskalova NI, Trukhin EV, Berestovitskaya VM (2015) Russ J Gen Chem 85:1845

Fringuelli F, Girotti R, Piermatti O, Pizzo F, Vaccaro L (2006) Org Lett 8:5741

Jasiński R, Rzyman M, Barański A (2010) Coll Czech Chem Commun 75:919

Fringuelli F, Matteucci M, Piermatti O, Pizzo F, Burla MC (2001) J Org Chem 66:4661

Jasiński R, Kubik M, Łapczuk-Krygier A, Kącka A, Dresler E, Boguszewska-Czubara A (2014) React Kinet Mech Catal 113:333

Amantini D, Fringuelli F, Piermatti O, Pizzo F, Zunino E, Vaccaro L (2005) J Org Chem 70:6526

Fringuelli F, Lanari D, Pizzo F, Vaccaro L (2008) Eur J Org Chem 23:3928

Jasiński R (2014) Comput Theor Chem 1046:93

Szczepanek A, Jasińska E, Kącka A, Jasiński R (2015) Curr Chem Lett 4:33

Jasiński R, Ziółkowska M, Demchuk OM, Maziarka A (2014) Central Eur J Chem 12:586

Jasiński R (2009) Coll Czech Chem Commun 74:1341

Jasiński R, Kwiatkowska M, Barański A (2009) J Mol Struct (TheoChem) 910:80

Jasiński R, Barański A (2010) J Mol Struct (TheoChem) 949:8

Domingo LR, Saez JA (2009) Org Biomol Chem 7:3576

Jasiński R (2015) J Fluorine Chem 176:35

Parham WE, Hasek WR (1953) J Am Chem Soc 76:799

Parham WE, Serres C, O’Connor PR (1957) J Am Chem Soc 80:588

Parham WE, Braxton HG, Serres C (1960) J Org Chem 26:1831

Gabitiv FA, Kremleva OB, Fridman AL (1976) Chem Heterocycl Comp 12:826

Franck-Neuman M, Miesch M (1984) Tetrahedron Lett 25:2909

Jasiński R (2013) Tetrahedron 69:927

Jasiński R (2015) Tetrahedron Lett 56:532

Huisgen R, Penelle J, Mloston G, Buyle-Padias A, Hall HK (1992) J Am Chem Soc 114:266

Jasiński R (2015) RSC Adv 5:101045

Gucma M, Gołębiewski MW, Michalczyk AK (2016) Monatsh Chem 147:1809

Gupta M, Gupta M, Paul S, Kant R, Gupta VK (2015) Monatsh Chem 146:143

Siadati SA (2016) Helv Chim Acta 99:273

Brower F, Burkett H (1953) J Am Chem Soc 75:1082

Grasse PB, Brauer BE, Zupancic JJ, Kaufmann KJ, Schuster GB (1983) J Am Chem Soc 105:6833

Oxford Diffraction Xcalibur CCD System (2009) CRYSALIS Software System Version 1.171. Oxford Diffraction Ltd. Abingdon, Oxfordshire, UK

CrysAlisPro Software System (2014) Version 1.171.37.34, Agilent Technologies, Oxford, UK

Sheldrick GM (2008) Acta Cryst A64:112

Dolomanov OV, Bourhis LJ, Gildea RJ, Howard JAK, Puschmann H (2009) J Appl Cryst 42:339

Fun HK, Chantrapromma S, Razak IA, Usman A, Ma W, Tian YP, Zhang SY, Wu JY, Xie FX (2001) Acta Cryst E57:o1043

Parr RG, von Szentpaly L, Liu LS (1999) J Am Chem Soc 121:1922

Domingo LR, Aurell MJ, Perez P, Contreras R (2002) Tetrahedron 58:4417

Dodziuk H, Demchuk OM, Bielejewska A, Koźmiński W, Dolgonos G (2004) Supramol Chem 16:287

Domingo LR, Chamorro E, Perez P (2008) J Org Chem 73:4615

Perez P, Domingo LR, Duque-Norena M, Chamorro E (2009) J Mol Struct (TheoChem) 895:86

Domingo LR, Perez P, Saez JA (2013) RSC Adv 3:1486

Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery Jr JA, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam NJ, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas O, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ (2009) Gaussian 09, Revision A.01. Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT

Jasiński R (2015) Monatsh Chem 146:591

Cossi M, Rega N, Scalmani G, Barone V (2003) J Comp Chem 24:669

Domingo LR (2014) RSC Adv 4:32415

Acknowledgements

The research was carried out with the equipment purchased thanks to the financial support of the European Regional Development Fund in the framework of the Operational Program Development of Eastern Poland 2007–2013 (Contract No. POPW.01.03.00-06-009/11-00, equipping the laboratories of the Faculties of Biology and Biotechnology, Mathematics, Physics and Informatics, and Chemistry for studies of biologically active substances and environmental samples). The authors thank also the Polish Ministry of Science and Education for financial support (Project No. C-2/259/2015/DS) as well as for Cracov Computing Centre “Cyfronet” for permission to use high-performance computers (Grant No. MNiSW/Zeus_lokalnie/PK/009/2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Jasiński, R., Kula, K., Kącka, A. et al. Unexpected course of reaction between (E)-2-aryl-1-cyano-1-nitroethenes and diazafluorene: why is there no 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition?. Monatsh Chem 148, 909–915 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00706-016-1893-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00706-016-1893-5