Abstract

Introduction

Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion (ACDF) and Anterior Cervical Corpectomy and Fusion (ACCF) are both common surgical procedures in the management of pathologies of the subaxial cervical spine. While recent reviews have demonstrated ACCF to provide better decompression results compared to ACDF, the procedure has been associated with increased surgical risks. Nonetheless, the use of ACCF in a traumatic context has been poorly described. The aim of this study was to assess the safety of ACCF as compared to the more commonly performed ACDF.

Methods

All patients undergoing ACCF or ACDF for subaxial cervical spine injuries spanning over 2 disc-spaces and 3 vertebral-levels, between 2006 and 2018, at the study center, were eligible for inclusion. Patients were matched based on age and preoperative ASIA score.

Results

After matching, 60 patients were included in the matched analysis, where 30 underwent ACDF and ACCF, respectively. Vertebral body injury was significantly more common in the ACCF group (p = 0.002), while traumatic disc rupture was more frequent in the ACDF group (p = 0.032). There were no statistically significant differences in the rates of surgical complications, including implant failure, wound infection, dysphagia, CSF leakage between the groups (p ≥ 0.05). The rates of revision surgeries (p > 0.999), mortality (p = 0.222), and long-term ASIA scores (p = 0.081) were also similar.

Conclusion

Results of both unmatched and matched analyses indicate that ACCF has comparable outcomes and no additional risks compared to ACDF. It is thus a safe approach and should be considered for patients with extensive anterior column injury.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Surgery has a fundamental role in the management of subaxial cervical spine injuries. Depending on the various mechanisms and extent of injury, a range of surgical methods and approaches may be used. Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion (ACDF) and Anterior Cervical Corpectomy and Fusion (ACCF) are both viable surgical approaches in the management of pathologies of the cervical spine [3, 11, 17, 19, 26, 28]. Although both largely established in spine surgery [23, 25], there are no clear guidelines surrounding the use of one or the other of the techniques in the setting of subaxial traumatic injuries. ACCF offers improved visualization of the injury site compared to ACDF [9] and recent reviews have demonstrated that ACCF provides better decompression results [7, 8, 28]. Nonetheless, certain reports indicate a higher perioperative complication risk associated with ACCF as compared to ACDF [18, 27]. Additionally, ACCF is more technically challenging, and its use within the context of cervical spine trauma is limited and poorly researched. In contrast, the use of ACDF for subaxial spinal injuries has been widely described within the literature. This discrepancy may arise from a reluctance to utilize ACCF due to its more invasive and risk-bearing profile.

Regardless of the approach, the goals of surgery remain decompression of the spinal cord, reduction and stabilization of the injured segment [2], and maintenance of cervical lordosis [13]. Adequate decompression of the spinal cord is essential for the prevention of increased intramedullary pressure with resulting reductions in the perfusion pressure, especially in the setting of a posttraumatic medullary edema [6, 8, 14].

In this retrospective single center study, data for all patients undergoing ACDF or ACCF for subaxial cervical spine injuries involving the fusion of three vertebrae, was reviewed. The aim of the study was to compare procedural and periprocedural complications and outcomes following ACDF or ACCF for the treatment of subaxial cervical spine injuries. This comparison seeks to delineate risk profile differences between ACCF and the more commonly used ACDF.

Methods

Patient selection

This study complies with all ethical guidelines and regulations and was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority. The study hospital is a publicly funded tertiary care center serving a region of approximately 2 million inhabitants. It is the region’s only level 1 trauma center and handles most of the spinal trauma cases in the region. Patients were identified through the surgical management software Orbit (Evry Healthcare Systems, Solna, Sweden). Medical records and imaging data from digital hospital charts were retrospectively reviewed using the health record software TakeCare (Compu Group Medical Sweden AB, Farsta, Sweden). The need for patient informed consent was waived, as per Swedish regulations on the use of retrospective patient data. The inclusion criteria were subaxial traumatic cervical spine injury, treated with 2-level ACDF or 1-level ACCF (surgeries spanning over 2 discs and fusing 3 vertebrae). The exclusion criteria were degenerative cases, non-traumatic cases, traumatic cases primarily treated with posterior or anteroposterior surgery, and cases with incomplete records. A total of 629 adult patients treated with ACDF or ACCF during the period of 2006 to 2018 were screened and 104 cases (54 ACDF and 50 ACCF) were included in the study. Preoperative diagnostic imaging included, in the vast majority, an initial trauma CT scan followed by an MRI. The cohort of patients undergoing ACDF was considered as the control group, given the established nature of the procedure in a traumatic context, as opposed to the ACCF.

Surgical technique

All surgeries were performed by at least one attending senior neurosurgeon. A standard right-sided Smith-Robinson approach was performed in all cases.

ACDF: following discectomy and osteophyte removal, decompression was performed using a high-speed drill at both levels. The posterior longitudinal ligament was typically not opened unless disrupted due to the trauma. PEEK cages were used in all cases.

ACCF: following discectomy above and below the intended vertebrae, corpectomy was performed using a high-speed drill. The posterior longitudinal ligament was typically removed. When using a titanium mesh cage (TMC), as done in 41 of the cases, a cage of appropriate dimensions was chosen, filled with the salvaged bone from the vertebra, and placed in the corpectomy defect. Expandable PEEK cages were otherwise used in six, and iliac crest autograft in three cases.

Adequate alignment and correct position of the cage was confirmed by fluoroscopy. An anterior plate was then positioned, bridging the vertebrae above and below the cage(s) and stabilized with bicortical screws under fluoroscopic guidance.

Postoperative follow-up

Patients were mobilized without collars after surgery. Postoperative clinical controls and a CT-scan were usually performed within the first 24 h. In adherence with routine protocols, all patients underwent follow-up CT scans at approximately 4 weeks and 3 months after initial surgery. All patients were clinically evaluated by their surgeon after 3 months. The median time to short-term follow-up in this cohort was 3 months (IQR: 1–5). Additional imaging, in selected cases, was performed when clinically indicated. The last clinical follow-ups were performed at a median of 76 months postoperatively.

Statistics and matching

For descriptive purposes, categorical data are presented as number (proportion). The normality of continuous data was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Since the distribution of all continuous data deviated significantly from a normal distribution pattern, medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) were used. Variables potentially interfering with the primary study outcome were identified based on previous studies. Case–control matching was then used to account for these potential confounders. Variables that were included in the matching process were age and the preoperative ASIA score, with degrees of freedom of 5 and 0, respectively. Owing to the inherent distinctions in surgical indications between ACDF and ACCF, there is a potential overrepresentation of more severe and extensive injuries among patients undergoing ACCF. This could introduce bias into the results, potentially exaggerating the surgical risks associated with this procedure. Therefore, the process of matching based on the aforementioned variables aims to establish cohorts with comparable severity of injuries, mitigating the impact of these underlying differences. Statistical significance was set to p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS and R.

Results

Unmatched analysis

In total 629 patients were screened and 104 patients undergoing ACDF or ACCF, both involving the removal of 2-discs and the fusion of 3 vertebrae, were identified and included in the unmatched analysis (Table 1). There was no significant difference in male sex distribution between ACDF and ACCF groups (70% vs 74%, p = 0.680). Patients in the ACDF group were significantly older than those in the ACCF group (62.9 vs 39 years, p < 0.001). No significant difference in body mass index (BMI) was found between the groups (25 vs 24, p = 0.122). Regarding trauma mechanism, the ACDF group had a higher proportion of patients experiencing fall from height (36% vs. 30%) and road traffic accidents (30% vs. 16%) compared to the ACCF group (p = 0.043).

Radiologically, a significant difference was found in the occurrence of traumatic disc ruptures between ACDF and ACCF groups (76% vs 50%, p = 0.006). Vertebral body injuries were, however, more common in the ACCF than the ACDF group (90% vs 52%, p < 0.001).

No significant differences were found in surgical complication rates, including wound infection, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak, dysphagia, other complications, and the composite outcome for any complication, between ACDF and ACCF groups (Table 2).

At long-term follow-up (median: 76 months; IQR: 76), there was no significant difference in the distribution of ASIA scores between the ACDF and ACCF groups (p = 0.319). There were no deaths recorded within the 30-day postoperative period, and only one death in the 90-day postoperative period. The patient who died had received an ACCF, but the death was unrelated to the procedure. In total, three patients died within one year of their injury, two of whom received an ACDF, and one an ACCF.

Matched analysis

After matching based on age and preoperative ASIA score, an analysis was performed comparing 30 cases with each approach (Table 1). There was no significant difference in the distribution of male sex (63% vs 70%, p = 0.584), age (49 vs 42 years, p = 0.220), BMI (24 vs 24, p = 0.987), trauma mechanism (p = 0.115), or preoperative ASIA scores between the two groups (p > 0.999).

Radiologically, significant differences were observed in the occurrence of traumatic disc rupture (ACDF: 77%, ACCF: 50%, p = 0.032) and vertebral body injury (ACDF: 53%, ACCF: 90%, p = 0.002). Surgery was performed on average within 48 h of the trauma, without any significant difference between the groups (p = 0.055).

Surgical complications, including wound infection, CSF leak, dysphagia, other complications, and the composite outcome for any complication, did not show significant differences between the ACDF and ACCF groups. The occurrence of construct failure and supplementary posterior fixation did not differ between the groups (p = 0.990).

No significant difference was found in the distribution of long-term (median: 76 months; IQR: 92) ASIA scores between ACDF and ACCF groups (p = 0.081), or the postoperative mortality rates (Table 2).

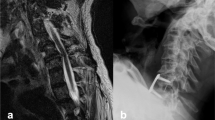

Pre- and postoperative CT and MRI imaging of two patients treated with 1-level ACCF and 2-level ACDF, respectively, is provided (Figs. 1 and 2).

Discussion

In this study, we reviewed our experience with two-level ACDF vs one-level ACCF for the treatment of subaxial cervical spine injuries, contrasting the two techniques regarding complications and outcomes. As expected, ACCF was more commonly performed in patients with vertebral body injury (p = 0.002), and ACDF in those with traumatic disc rupture (p = 0.032). With greater severity of injury, i.e. vertebral body injury, ACCF was favored. ACCF is known to be technically more challenging and carries a higher risk of complications, such as injury to the dura, spinal cord, or nerve roots [10, 15, 21, 30]. However, in this study the complications and clinical outcomes did not significantly differ between ACDF and ACCF groups. This is in line with previous literature on degenerative cervical spine surgery, which revealed similar outcomes and complication rates between one-level ACCF and two level ACDF. The only differences seen between the two procedures concerned operative time, blood loss, and length of hospital stay, all in favor of ACDF [5, 12, 22].

Evidence provided by studies on degenerative cervical spine suggest a higher degree of decompression achieved with ACCF compared to ACDF [1, 10, 15, 24, 24]. This should arguably be the case even in the context of traumatic cervical spine injuries, although very few studies describe the role of ACCF in the management of cervical spine injuries. Nonetheless, our findings provide evidence for the safety of ACCF in the treatment of subaxial cervical spine injuries. ACCF provided adequate decompression of the spinal cord and comparable neurological outcomes to ACDF, without any additional complications. In a nationwide matched analysis comparing ACDF to ACCF based on data from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP), the authors reached similar conclusions and suggested the use of the procedure that best accomplishes the surgical objectives [5]. Interestingly, in that study, ACCF was associated with major postoperative adverse events. This association, however, was later revoked, after adjusting for operative time, where the operative time was a larger risk factor for complications than the approach itself [5]. Efforts should be made to select the right patients, and surgeon, for the procedure, rather than avoiding ACCF for fear of its risk profile.

In fact, a gap in the literature regarding the use of ACCF in the treatment of subaxial cervical spine injuries was detected as only a few studies with limited sample sizes were found. More studies analyzing the outcomes of ACCF in the treatment of cervical spine injuries are warranted to increase the understanding of the risks and benefits of the procedure.

In their series of 99 patients, Madan et al. found ACCF to yield good clinical outcomes regarding postoperative disability and neurological function. Most of the patients (90%) reported mild to no disability on the neck disability index (NDI) and 59% scored ASIA E at last follow-up (vs. 34% on admission). No patients experienced any neurological deterioration [2]. Similarly, in our study most patients (60%) had a long-term postoperative ASIA score of E (vs. 38% on admission) and no patients experienced deterioration.

In a study from a low resource setting on 14 patients undergoing ACCF for subaxial spine injuries, 58% of the patients experienced neurological improvements postoperatively, which is in line with our results (51%). However, a considerably higher rate of complications was reported compared to our results (57% vs. 12%), most likely owing to the differences in settings [4].

The aim of this study was to investigate if ACCF was associated with a higher complication rate compared to ACDF. In the direct comparison between the two treatments no differences were found. To ensure that the lack of difference was not explained by baseline differences between the groups, a matching was performed based on patient age and admission AIS scores. These variables have repeatedly been identified as outcome predictors in the management of traumatic spine injuries [4]. Matching did not affect the outcome of the comparison between ACCF and ACDF.

While we have not fund increased risks associated with ACCF as compared to ACDF, it must be acknowledged that the indications differ between the two procedures. It could be argued that matching based on neurology disregards the more extensive vertebral body injuries associated with spinal cord injury on the one hand and uncomplicated ligamentous injuries treated with ACDF on the other.

Yet, the unmatched analysis failed to reveal noteworthy differences, despite an anticipated higher complication rate within the ACCF-group.

Regardless, the surgeon's decision-making process should prioritize a comprehensive understanding of the underlying pathology rather than solely relying on the statistical risk of complications. This distinction is crucial as the two procedures, while occasionally overlapping, cater to different surgical indications.

Finally, in the context of traumatic cervical spine injuries, there is a need for randomized controlled trials to evaluate the contribution of ACCF relative to ACDF in patients eligible for both approaches.

Strengths and limitations

This study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to compare the surgical complications and long-term outcomes following ACCF or ACDF surgeries spanning over 2 discs and fusing 3 vertebrae in the treatment of subaxial cervical spine injuries. Case–control matching was used to account for the effect of potential confounders. The study limitations include its retrospective and single-center design. Moreover, variables such as baseline comorbidity, operative time, blood loss, and length of stay were unavailable and were not accounted for in the comparative analysis. Among all patients screened, only 104 and 60 were included in the unmatched and matched analyses, respectively. This relatively small sample size nonetheless represents the largest cohort to date on ACCF for traumatic injuries. Finally, an important limitation has to do with the generalizability of the findings, given the fact that all procedures were performed in a highly specialized center with extensive experience with both procedures.

Conclusion

In this study, subaxial cervical spine injuries treated with either ACDF or ACCF spanning over two disc-spaces and three vertebral levels were compared. Despite a greater injury severity in patients receiving ACCF, the frequency of postoperative complications and instrument failure did not differ between approaches. Treatment with ACCF demonstrated comparable long-term neurological outcomes to ACDF. This study provides evidence suggesting similar risk profiles between ACCF and ACDF. In the hands of experienced surgeons, ACCF is a relatively safe approach without increased risk of morbidity and warrants consideration for patients with extensive vertebral injury.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Aly MH, Elashry AH, Elkatatny AAAM (2021) Corpectomy in sub-axial cervical fracture in tertiary center in third world country. Med J Cairo Univ 89(1):257–65

Ashkenazi E, Smorgick Y, Rand N, Millgram MA, Mirovsky Y, Floman Y (2005) Anterior decompression combined with corpectomies and discectomies in the management of multilevel cervical myelopathy: a hybrid decompression and fixation technique. J Neurosurg Spine 3(3):205–209

Badhiwala JH, Wilson JR, Witiw CD, Harrop JS, Vaccaro AR, Aarabi B et al (2021) The influence of timing of surgical decompression for acute spinal cord injury: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Neurol 20(2):117–126

Bohlman HH, Emery SE, Goodfellow DB, Jones PK (1993) Robinson anterior cervical discectomy and arthrodesis for cervical radiculopathy. Long-term follow-up of one hundred and twenty-two patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 75(9):1298–307

Chen Z, Liu B, Dong J, Feng F, Chen R, Xie P et al (2016) Comparison of anterior corpectomy and fusion versus laminoplasty for the treatment of cervical ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament: a meta-analysis. Neurosurg Focus 40(6):E8

Cho BY, Lim J, Sim HB, Park J (2010) Biomechanical analysis of the range of motion after placement of a two-level cervical ProDisc-C versus hybrid construct. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 35(19):1769–76

Cloward RB (1958) The anterior approach for removal of ruptured cervical disks. J Neurosurg 15(6):602–617

Dhaliwal P, Gomez A, Zeiler FA (2023) Case report: continuous spinal cord physiologic monitoring following traumatic spinal cord injury-a report from the Winnipeg Intraspinal Pressure Study (WISP). Front Neurol 14:1069623

Dorai Z, Morgan H, Coimbra C (2003) Titanium cage reconstruction after cervical corpectomy. J Neurosurg 99(1 Suppl):3–7

Emery SE, Bohlman HH, Bolesta MJ, Jones PK (1998) Anterior cervical decompression and arthrodesis for the treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Two to seventeen-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 80(7):941–51

Fessler RG, Steck JC, Giovanini MA (1998) Anterior cervical corpectomy for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Neurosurgery 43(2):257–65; discussion 65–7

Galivanche AR, Gala R, Bagi PS, Boylan AJ, Dussik CM, Coutinho PD et al (2020) Perioperative outcomes in 17,947 patients undergoing 2-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion versus 1-level anterior cervical corpectomy for treatment of cervical degenerative conditions: a propensity score matched national surgical quality improvement program analysis. Neurospine 17(4):871–878

Goffin J, Geusens E, Vantomme N, Quintens E, Waerzeggers Y, Depreitere B et al (2004) Long-term follow-up after interbody fusion of the cervical spine. J Spinal Disord Tech 17(2):79–85

Hwang SL, Lee KS, Su YF, Kuo TH, Lieu AS, Lin CL et al (2007) Anterior corpectomy with iliac bone fusion or discectomy with interbody titanium cage fusion for multilevel cervical degenerated disc disease. J Spinal Disord Tech 20(8):565–570

Katz AD, Mancini N, Karukonda T, Cote M, Moss IL (2019) Comparative and predictor analysis of 30-day readmission, reoperation, and morbidity in patients undergoing multilevel ACDF versus single and multilevel ACCF using the ACS-NSQIP dataset. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 44(23):E1379–E87

Kristof RA, Kiefer T, Thudium M, Ringel F, Stoffel M, Kovacs A et al (2009) Comparison of ventral corpectomy and plate-screw-instrumented fusion with dorsal laminectomy and rod-screw-instrumented fusion for treatment of at least two vertebral-level spondylotic cervical myelopathy. Eur Spine J 18(12):1951–1956

Lee MJ, Dumonski M, Phillips FM, Voronov LI, Renner SM, Carandang G et al (2011) Disc replacement adjacent to cervical fusion: a biomechanical comparison of hybrid construct versus two-level fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 36(23):1932–9

Lo C, Tran Y, Anderson K, Craig A, Middleton J (2016) Functional priorities in persons with spinal cord injury: using discrete choice experiments to determine preferences. J Neurotrauma 33(21):1958–1968

Madan A, Thakur M, Sud S, Jain V, Singh Thakur RP, Negi V (2019) Subaxial cervical spine injuries: outcomes after anterior corpectomy and instrumentation. Asian J Neurosurg 14(3):843–847

Oh MC, Zhang HY, Park JY, Kim KS (2009) Two-level anterior cervical discectomy versus one-level corpectomy in cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 34(7):692–6

Qiu Y, Xie Y, Chen Y, Ye J, Wang F, Zeng J et al (2020) Adjacent two-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion versus one-level corpectomy and fusion in cervical spondylotic myelopathy: Analysis of perioperative parameters and sagittal balance. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 194:105919

Radcliff KE, Limthongkul W, Kepler CK, Sidhu GD, Anderson DG, Rihn JA et al (2014) Cervical laminectomy width and spinal cord drift are risk factors for postoperative C5 palsy. J Spinal Disord Tech 27(2):86–92

Rogers WK, Todd M (2016) Acute spinal cord injury. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 30(1):27–39

Ryken TC, Heary RF, Matz PG, Anderson PA, Groff MW, Holly LT et al (2009) Cervical laminectomy for the treatment of cervical degenerative myelopathy. J Neurosurg Spine 11(2):142–149

Smith GW, Robinson RA (1958) The treatment of certain cervical-spine disorders by anterior removal of the intervertebral disc and interbody fusion. J Bone Joint Surg Am 40-A(3):607–24

Tatter C, Persson O, Burstrom G, Edstrom E, Elmi-Terander A (2020) Anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion for degenerative and traumatic spine disorders, single-center experience of a case series of 119 patients. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 20(1):8–17

Theodore N, Martirosyan N, Hersh AM, Ehresman J, Ahmed AK, Danielson J, Sullivan C, Shank CD, Almefty K, Lemole GM Jr, Kakarla UK, Hadley MN (2023) Cerebrospinal fluid drainage in patients with acute spinal cord injury: a multi-center randomized controlled trial. World Neurosurg S1878-8750(23):00846-X. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2023.06.078

Wang T, Wang H, Liu S, An HD, Liu H, Ding WY (2016) Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion versus anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion in multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 95(49):e5437

Wei-bing X, Wun-Jer S, Gang L, Yue Z, Ming-xi J, Lian-shun J (2009) Reconstructive techniques study after anterior decompression of multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Spinal Disord Tech 22(7):511–515

Wen Z, Lu T, Wang Y, Liang H, Gao Z, He X (2018) Anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion and anterior cervical discectomy and fusion using titanium mesh cages for treatment of degenerative cervical pathologies: a literature review. Med Sci Monit 24:6398–6404

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute. None of the authors received funding. AET is supported by Region Stockholm in a clinical research appointment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VGE. wrote the main manuscript text and prepared figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Participant consent and ethics statement

The need for patient consent was waved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority, as per Swedish laws on the use of retrospective patient data. This study complies with all ethical regulations and was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr: 2016/1708–31/4).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

El-Hajj, V.G., Singh, A., Fletcher-Sandersjöö, A. et al. Safety of anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion (ACCF) for the treatment of subaxial cervical spine injuries, a single center comparative matched analysis. Acta Neurochir 166, 280 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-024-06172-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-024-06172-1