Abstract

Purpose

To compare the complication rates of two different types of posterior instrumentation in patients with MMC, namely, definitive fusion and fusionless surgery (growing rods).

Methods

Single-center retrospective study of 30 MMC patients that underwent posterior instrumentation for deformity (scoliosis and/or kyphosis) treatment from 2008 until 2020. The patients were grouped based on whether they received definitive fusion or a growth-accommodating system, whether they had a complication that led to early surgery, osteotomy or non-osteotomy. Number of major operations, Cobb angle correction and perioperative blood loss were the outcomes.

Results

18 patients received a growing system and 12 were fused at index surgery. The growing system group underwent a mean of 2.38 (± 1.03) surgeries versus 1.91 (± 2.27) in the fusion group, p = 0.01. If an early revision was necessitated due to a complication, then the number of major surgeries per patient was 3.37 (± 2.44) versus 1.77 (± 0.97) in the group that did not undergo an early revision, p = 0.01. Four patients developed a superficial and six a deep wound infection, while loosening/breakage occurred in 10 patients. The Cobb angle was improved from a mean of 69 to 22 degrees postoperatively. Osteotomy did not lead to an increase in perioperative blood loss or number of major operations.

Conclusion

Growing systems had more major operations in comparison with fusion surgery and early revision surgery led to higher numbers of major operations per patient; these differences were statistically significant. Definitive fusion at index surgery might be the better option in some MMC patients with a high-risk profile.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Coronal and sagittal imbalance of the spine is a prevalent sequela in patients with meningomyelocele (MMC) and is either developmental in nature or as a result of a coexisting malformation (e.g., hemivertebrae) [1]. Spine surgery for meningomyelocele (MMC) is usually performed electively with the exceptions of postnatal MMC closure and perhaps decompressive upper cervical laminectomy in case of Chiari II malformations [2, 3]. Patients with scoliosis, which is defined as having a Cobb angle of more than 20° [4], may need spinal fusion surgery if the curve is greater than 40–50° at skeletal maturity. Otherwise, skeletally immature patients with curve rigidity [1, 5], tethered spinal cord, suboptimal sitting balance, patients requiring the use of upper limbs for balance, or patients with deteriorated pulmonary function and marked pelvic obliquity are all candidates for operation [6]. Another indication for operative treatment is rigid lumbar and thoracolumbar kyphosis causing recalcitrant skin ulcerations at the gibbus site [7].

Operative methods

Both posterior lateral fixation (PLF) and anterior spinal fixation are common surgical practices [8, 9]. Although pelvic obliquity can be addressed satisfactorily with sacropelvic sparring PLF and tautochronous anterior fixation [10], inclusion of the sacrum and pelvis in the fusion confers superior correction results; this can be done with S1 screws, Galveston technique, iliac screws, sacral alar fixation (S2) screws [11]. In order to strengthen the construct, a horizontal rod can bridge both sides of the pelvis with the sacrum in a “segmental T-assembly” [12].

Because patients with MMC are typically young in age, growing systems (fusionless surgery) offer advantages in terms of preservation of spinal growth. The main drawback of growing systems such as growing rods and vertical expandable prosthetic titanium ribs (VEPTR) is that they require additional surgeries for lengthening, exposing the patient to surgical and anesthesia risks [13]. A retrospective study by Bess et al. from 2010 [14] showed that 18% of the patients that received double growing rods experienced wound complications, while the risk for complications increased with each additional surgery by 24%. Implant problems such as loosening/breakage or implant prominence manifested in 34% of the patients. The growth guidance technique (Shilla®) [15] alleviates the need of repetitive lengthening surgeries, and even though the infection rates are different between different growth systems, the overall complication rate is similar [16]. Other disadvantages of the fusionless surgery is the stiffening of the spine (law of diminishing returns), where the Cobb angle stops improving after approximately three years of treatment [17] and the crankshaft phenomenon which is a progressive deformity, despite fusion due to remaining growth potential of the spine [18]. On the other hand, definitive fusion surgery seems to mitigate some of these risks. Standalone posterior fusions in MMC have a reported infection rate 7% [19, 20], rod breakage 20% [20], while putting screws at the apex of the curves hinders the development of the crankshaft phenomenon [12]. In a single-surgeon retrospective study of 12 non-ambulatory MMC cases of anterolateral fusion with a 6-mm titanium rod [21], there were no delayed complications in the form of pseudarthrosis, rod breakage and deep wound infections, achieving satisfactory curve correction and improved quality of life.

In this retrospective analysis, we are presenting a review of the treatment of MMC cases in our institution, from 2008 to 2020. Particular focus was given in complications, reoperations rate and correction in relation to fusion or fusionless techniques and although this is a descriptive study, it concerns a rare patient group.

The majority of the cases presented in this study consists of patients treated with guiding rods (McCarthy Dunn technique and Shilla®). Kyphectomy was performed when needed, with fusion and PLF (Werner Fackler technique). In the fusion cases, the pelvis was routinely included for a better correction of pelvic obliquity and due to the lack of any muscle tone caudal to the lesion.

Materials and methods

Thirty patients with MMC that underwent spine surgery at the University hospital of Uppsala from 2008 to 2020 were included in this study. The study was approved by the regional committee for research and ethics (DNR 2019–02345). The patients were sub-grouped in those that were operated on with growing rods (n = 18) versus definitive fixation at index surgery (n = 12), and in those that underwent osteotomy (n = 9) versus no osteotomy (n = 21). Osteotomy was either pedicle subtraction osteotomy (PSO) or vertebral column resection (VCR). Differences between the means were compared with the Mann–Whitney test and paired student t-test. R studio [22] was used for graph design and statistics. The results are expressed as mean (± SD) unless stated otherwise.

Index surgery and major operations and complications

The index surgery (with or without osteotomy) was either installation of a growing system or definitive fusion. All subsequent surgeries following index surgery were considered major operations, except for VAC changes and planned elongations. The main complications cataloged were infections (deep and superficial), early (< 1 year) and late (> 1 year) loosening/rod breakage and dural tears.

Curve correction and osteotomy

The primary objective for curve correction was for the patient to obtain a horizontal gaze as well as the ability to sit without the development of pressure sores. Eventual kyphosis causing excessive forward leaning to the patient had to be corrected. Preoperative and postoperative Cobb angles on frontal spine X-rays were and the values were compared with a paired t-test. The risk for increased perioperative bleeding in relation to undergoing osteotomy was calculated with non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-tests.

Results

Patient demographics and comorbidities

There were 21 male and nine female patients, and the average age at surgery was 9.6 years (Table 1). Most of the patients had a concomitant Chiari type 2 malformation, while 23 had some degree of bladder dysfunction. The majority of the patients had to undergo spinal cord release surgery either at the same time as index surgery (n = 13) or prior to index surgery (n = 8). Plastic expanders for skin expansion prior to index surgery were the case for 18/30 patients. Only two patients were fully neurologically functional, in the sense that they could ambulate independently.

Amount of major surgeries

The majority of the 30 patients that were operated on received a growing system at index surgery (n = 18), while 12 patients underwent definitive fixation primarily (Table 1). In 21 cases, the curve was corrected without the need for an osteotomy. The implants used in each index surgery are listed in Table 1.

There were 64 major operations both for those that received definitive fusion and for those that received a growing system at index surgery. In general, the patients operated with a growing system (n = 18) underwent a significantly increased number of major reoperations compared to patients operated with a final fusion (n = 12), 2.38 (± 1.03) versus 1.91 (± 2.27), respectively, p = 0.01 (Fig. 1a). The fusion group had a lower reoperation rate than the growing system group. The outlier in the fusion group was a case of a 15-year-old boy that developed deep infection and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage and required multiple subsequent revision surgeries.

Graphs of major surgeries per patient; a. number of major operations depending on type of index surgery; b. major operations based on whether they had a complication that led to early surgery. The red dot signifies the mean and the brackets the standard deviation (p values calculated with Mann–Whitney-Wilcoxon test)

Complications

Patients that suffered from a complication that led to early surgery (n = 8), had to undergo a mean of 3.37 (± 2.44) major surgeries, which was statistically significantly higher than the rest of the patients (n = 22) that had a mean of 1.77 (± 0.97) major surgeries, p = 0.01 (Fig. 1b). The most common complication was deep wound infection that occurred in 21% of the patients (n = 7) and required surgical revision (Table 2). Late loosening or rod breakage occurred also in 21% of the patients, while early loosening happened in 12% of the total amount of cases (n = 4). Also, accidental dural tear occurred inadvertently in six cases out of 17 (35%), in two of these cases, the CSF leak was persistent. The first of the two cases was a definitive fusion with osteotomy on a 10-year-old girl that had to be revised with wound exploration and suturing of the dural tear. The second case was a definitive fusion without osteotomy on a 15-year-old-boy that developed a deep wound infection that had to undergo eight revision surgeries. The persistent CSF leak stopped in both cases after a ventricular shunt was placed by the neurosurgeons. Note that in 13 out of 30 patients, there was an intentional opening of the dural sack because of spinal cord release, this is why we count the six accidental dural tears out of 17 and not 30 patients.

Deformity correction and perioperative blood loss

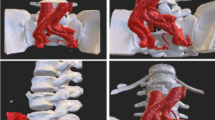

The majority of the patients had more than one curve that needed correction, thereby comparisons of multiple curves for each patient were enabled. However, because of missing records, we were able to compare the pre- and postoperative x-rays in 15 out of 30 patients. Thus, there were n = 7 lumbar, n = 12 thoracic, n = 4 thoracolumbar and n = 10 sagittal pre- and postoperative x-rays (Fig. 2). The most marked corrections were observed in the lumbar spine, where the preoperative Cobb value was 62.83 (± 17.53) and the postoperative value was 12.67 (± 13.03), p < 0.001.

An association between osteotomy or VCR with the amount of perioperative blood loss or the number of major reoperations was not found. The osteotomy group (n = 8) had a mean bleeding of 533.12 (± 396.85) mL, while the rest of the patients (n = 19) had a mean of 1147.68 (± 931.39) mL, p = 0.73 (Fig. 3a). Similarly, osteotomy (n = 9) did not lead to increased number of major operations, with a mean of 2 (± 0.70) versus 2.28 (± 1.90) operations in the rest of the patients (n = 21), p = 0.56 (Fig. 3b).

Discussion

The purpose of spine surgery in MMC is to address the patients’ postural problems, primarily while sitting in the wheelchair. High Cobb values are an indication for surgery as well, as high-grade scoliosis is not compatible with life [10].

A generally acceptable practice for younger children is the use of growing systems instead of definitive fixation, in order to avoid stunting trunk growth [23]. In our series, 33% (10/30 patients) developed a postoperative infection, 10% (3/10) was superficial wound infection that went on remission with oral antibiotics, while 23% was deep wound infection that necessitated revision surgeries. It has been advocated that growing systems do not significantly increase complication rates in comparison with fusions [19], as long posterior instrumentations are also thought to be coupled with increased risk for postoperative infections [21, 24]. In the present retrospective study, growing rods increased the number of major surgeries by 25% in comparison to definitive fusion, a difference that was statistically significant. A complication that led to early surgery also led to a 100% increase in the number of major operations per patient. A 2021 study by Johnston et al. [25]of patients with early-onset scoliosis raised questions about the validity of relying solely on the thoracic spine height threshold (18 cm) as an effective measure for treatment outcomes. It was shown that residual curves of ≥ 50 degrees, and not the age at index surgery (< 5 or ≥ 5 years) nor the thoracic height were correlated with worse pulmonary function tests. Thus, a case can be made that the function in children with MMC may not be affected, in spite of limited vital capacity, and for that reason definite fusion might be an option even in younger age.

Out of the 12 MMC patients that underwent definitive posterior fusion, 7 (58%) were fused to the sacrum in order to better address the correction of their deformity, which also been shown to improve the patients’ sitting ability [24]. It has been suggested however that if acceptable deformity correction is achievable, ending the construct at L4 allows for better mobility of the patients in their wheelchairs [21]. In Araujo’s [26] retrospective study from 2021 of MMC patients with a standalone posterior fusion, they achieved a mean Cobb angle correction of 47 degrees in 34 patients (mean 102 degrees preoperatively and 55 degrees postoperatively). In our current series, we achieved an average correction of 47 degrees, from 69 degrees preoperative to 22 degrees postoperatively. In the 9 patients that kyphosis was addressed, we achieved a correction of 92% [from 66,2 (± 42,5) degrees preoperatively, to 5,6 (± 30,8) degrees]. Concordantly, in a retrospective study of 30 MMC patients from Özcan et al. [27], treated with growing rods, a 96% correction of the kyphotic deformity was reported, from a mean 115 degrees preoperative to 5,1 postoperatively.

The group that underwent osteotomy or VCR did not have a statistically significant difference from the non-osteotomy group, in regard neither to major reoperations nor in the amount of bleeding. To that might have contributed the development of our surgical technique, the use of tranexamic acid and pedicle screw navigation system that have been evolved and are now routinely used in our institution. These findings are in accordance with the literature, whereby blood loss and operative time have not been clearly coupled with higher risk for infection [26]. In accordance with these previous findings, we did not find a correlation between blood loss and infection.

Although meningomyelocele is a rare clinical entity, a limitation of the present study is the small number of patients included (n = 30). In 15 patients, the measurement of the change in the Cobb angle was not feasible due to missing records. Another weakness lies in the studies retrospective design but performing an RCT would be a difficult, if not impossible, endeavor.

Conclusion

Growing systems led to a significantly higher number of major reoperations compared to final fusions. Complications that led to early surgery were associated to a higher number of major reoperations. Osteotomy or VCR was not correlated with the amount of perioperative blood loss, nor the number of major reoperations. The patients’ postural problems improved after surgery and they were satisfied, despite complications such as revision surgeries. The option of choosing a system for definitive fusion should be strongly considered, especially in patients close to adolescence because the significantly lower risk of developing complications. In our patient group, the oldest patients that underwent correction with growing rods were two 10-year-old patients, while the youngest three patients that underwent correction with fusion were one 10 years old, one 11 years old and a one 12 years old. There were totally 12 patients that were fused (median of 13.5 and a 0.25, 0.75 IQR of 12.7 and 14.2 years, respectively). Thus, 10 years of age might represent a gray zone for definitive fusion, however, if the patient is in urgent need of surgery and is from 11 to 12 years old, then deformity correction with fusion could be appropriate.

References

Guille JT, Sarwark JF, Sherk HH, Kumar SJ (2006) Congenital and developmental deformities of the spine in children with myelomeningocele. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 14(5):294–302

McLone DG (1998) Care of the neonate with a myelomeningocele. Neurosurg Clin N Am 9(1):111–120

Messing-Junger M, Rohrig A (2013) Primary and secondary management of the Chiari II malformation in children with myelomeningocele. Childs Nerv Syst 29(9):1553–1562

Trivedi J, Thomson JD, Slakey JB, Banta JV, Jones PW (2002) Clinical and radiographic predictors of scoliosis in patients with myelomeningocele. J Bone Joint Surg Am 84(8):1389–1394

Tsirikos AI, Mains E (2012) Surgical correction of spinal deformity in patients with cerebral palsy using pedicle screw instrumentation. J Spinal Disord Tech 25(7):401–408

Altiok H, Riordan A, Graf A, Krzak J, Hassani S (2016) Response of scoliosis in children with myelomeningocele to surgical release of tethered spinal cord. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 22(4):247–252

Altiok H, Finlayson C, Hassani S, Sturm P (2011) Kyphectomy in children with myelomeningocele. Clin Orthop Relat Res 469(5):1272–1278

Geiger F, Parsch D, Carstens C (1999) Complications of scoliosis surgery in children with myelomeningocele. Eur Spine J 8(1):22–26

Mummareddy N, Dewan MC, Mercier MR, Naftel RP, Wellons JC 3rd, Bonfield CM (2017) Scoliosis in myelomeningocele: epidemiology, management, and functional outcome. J Neurosurg Pediatr 20(1):99–108

Wild A, Haak H, Kumar M, Krauspe R (2001) Is sacral instrumentation mandatory to address pelvic obliquity in neuromuscular thoracolumbar scoliosis due to myelomeningocele? Spine 26(14):E325–E329

Funk S, Lovejoy S, Mencio G, Martus J (2016) Rigid instrumentation for neuromuscular scoliosis improves deformity correction without increasing complications. Spine 41(1):46–52

Vialle R, Thevenin-Lemoine C, Mary P (2013) Neuromuscular scoliosis. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 99(1 Suppl):S124–S139

Odent T, Ilharreborde B, Miladi L, Khouri N, Violas P, Ouellet J, Cunin V, Kieffer J, Kharrat K, Accadbled F (2015) Fusionless surgery in early-onset scoliosis. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 101(6):S281–S288

Bess S, Akbarnia BA, Thompson GH, Sponseller PD, Shah SA, El Sebaie H, Boachie-Adjei O, Karlin LI, Canale S, Poe-Kochert C, Skaggs DL (2010) Complications of growing-rod treatment for early-onset scoliosis: Analysis of one hundred and forty patients. J Bone Joint Surg 92(15):2533–2543

McCarthy RE, McCullough FL (2014) Shilla growth guidance for early-onset scoliosis: results after a minimum of five years of follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 97(19):1578–1584

Kim G, Sammak SE, Michalopoulos GD, Mualem W, Pinter ZW, Freedman BA, Bydon M (2022) Comparison of surgical interventions for the treatment of early-onset scoliosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurosurg Pediatr 31(4):342–357

Sankar WN, Skaggs DL, Yazici M, Johnston CE, Shah SA, Javidan P, Kadakia RV, Day TF, Akbarnia BA (2011) Lengthening of dual growing rods and the law of diminishing returns. Spine 36(10):806–809

B. Dohin, J.F. Dubousset (1994) European Spree Journal Prevention of the crankshaft phenomenon with anterior spinal epiphysiodesis in surgical treatment of severe scoliosis of the younger patient, Eur Spine J, pp. 165–168.

Canaz H, Alatas I, Canaz G, Gumussuyu G, Cacan MA, Saracoglu A, Ucar BY (2018) Surgical treatment of patients with myelomeningocele-related spine deformities: study of 26 cases. Childs Nerv Syst 34(7):1367–1374

Mazur MBMJ, Dickens DR, Doig WG (1986) Efficacy of surgical management for scoliosis in myelomeningocele: correction of deformity and alteration of functional status. J Pediatr Orthop 6(5):568–575

Tsirikos AI, Wordie SJ (2021) The surgical treatment of spinal deformity in children with non-ambulatory myelomeningocele. Bone Joint J 103:1133–1141

R Core Team (2021) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/.

J.P. Can E Bas, Zeynep D Olgun, (2015) Gokhan Demirkiran, Paul Sponseller, Muharrem Yazici, Safety and Efficacy of Apical Resection Following Growth-friendly Instrumentation in Myelomeningocele Patients With Gibbus: Growing Rod Versus Luque Trolley. J Pediatr Orthop 35(8):e98-103

Efficacy of surgical management for scoliosis in myelomeningocele: correction of deformity and alteration of functional status.

C.E. Johnston, L.A. Karol, D. Thornberg, C. Jo, P. Eamara (2021) The 18-cm Thoracic-Height Threshold and Pulmonary Function in Non-Neuromuscular Early-Onset Scoliosis: A Reassessment, JB & JS open access 6(4)

de Araujo AO, Gomes CR, Fava D, Borigato EVM, Duarte LMR, de Oliveira RG (2021) Short-term surgical complications of spinal fusion in myelomeningocele. Spine Deform 9(4):1151–1159

Özcan Ç, Polat Ö, Alataş İ, Çamur S, Sağlam N, Uçar BY (2020) Clinical and radiological results of kyphectomy and sliding growing rod surgery technique performed in children with myelomeningocele. J Orthop Surg Res 15(1):576–576

Funding

Open access funding provided by Uppsala University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors state that they have no conflicts of interest to declare in regard to the present work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kontakis, M.G., Pazarlis, K., Karlsson, T. et al. Growing rods in meningomyelocele lead to increased risk for complications in comparison with fusion; a retrospective study of 30 patients treated for at the University Hospital of Uppsala. Eur Spine J 33, 739–745 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-023-07996-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-023-07996-8