Abstract

Purpose

The etiology of neck/shoulder pain is complex. Our purpose was to investigate if respiratory disorders are risk factors for troublesome neck/shoulder pain in people with no or occasional neck/shoulder pain.

Methods

This prospective cohort study was based on the Stockholm Public Health Cohorts (SPHC) 2006/2010 and the SPHC 2010/2014. We included adults who at baseline reported no or occasional neck/shoulder pain in the last six months, from the two subsamples (SPHC 06/10 n = 15 155: and SPHC 2010/14 n = 25 273). Exposures were self-reported asthma at baseline in SPHC 06/10 and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) at baseline in SPHC 10/14. The outcome was having experienced at least one period of troublesome neck/shoulder pain which restricted work capacity or hindered daily activities to some or to a high degree during the past six months, asked for four years later. Binomial regression analyses were used to calculate risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

Results

Adjusted results indicate that those reporting to suffer from asthma at baseline had a higher risk of troublesome neck/shoulder pain at follow-up four years later (RR 1.48, 95% CI 1.10–2.01) as did those reporting to suffer from COPD (RR 2.12 95%CI 1.54–2.93).

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that those with no or occasional neck/shoulder pain and reporting to suffer from asthma or COPD increase the risk for troublesome neck/shoulder pain over time. This highlights the importance of taking a multi-morbidity perspective into consideration in health care. Future longitudinal studies are needed to confirm our findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Musculoskeletal pain in the neck and upper body is common and has a considerable impact on the individual’s work ability and the health care systems [1,2,3]. In 2015, neck pain together with low back pain also was the leading cause of disability in most countries measured in years lived with disability (YLD) as measured in the Global Burden of Disease study [4, 5]. The estimated one-year incidence of neck pain is around 20% with a higher incidence noted in office and computer workers and reportedly higher in women [1, 2]. Chronic neck pain (> 3 months) has increased > 20% during the last decade and a reason for this may be an aging population around the world [5].

Several determinants of neck pain have been suggested. A study on the long-term prognosis of neck pain showed that biomechanical exposures such as manual handling and working with the hands above shoulder level have negative influences on the prognosis of neck pain [6]. In addition, the importance of lifestyle factors as well as job-related factors such as job strain has been highlighted for no or occasional neck and shoulder pain to become troublesome [7,8,9,10]. Further, individuals who lose time at work due to sick leave because of neck pain seem to be at higher risk for subsequent episodes of lost time at work and prolonged disability due to neck pain [11].

The prevalence of chronic neck and back pain in people suffering from respiratory disorders has recently been reported [12,13,14]. de Miguel-Díez et al. [12] investigated a cohort suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and 40% of those reported chronic neck pain while 45% reported chronic low back pain. Aligning with that, Bentsen et al. (2020), found that 47% of a Norwegian cohort of peoples with COPD reported neck/back pain and raised the question that more knowledge is needed how pain interferes with the lives of those suffering from COPD. A recent cross-sectional study that investigated risk factors for the development of neck and shoulder pain suggested that exercises that enhance breathing and heart rate were associated with a reduced risk of experiencing neck or shoulder pain, but there was no association between general physical activity and upper body pain [10]. The diaphragm and other important breathing muscles are suggested to play a role in postural control [15] as well as in spinal stiffness [16]. It has in addition been suggested that people with neck pain have an impaired respiratory dysfunction due to the thoracic mobility and the functions of the neck muscles [17,18,19,20]. A recent review further reported a significant difference in maximum inspiratory and expiratory pressures in patients with chronic neck pain compared to asymptomatic subjects [21]. Among respiratory disorders, COPD is a chronic condition that leads to a pathologic degeneration of the respiratory system [22,23,24]. Moreover, in people suffering from asthma, hyperventilation is a problem affecting the breathing muscles and consequently the neck, shoulder, and the thoracic region [25, 26]. During an asthma attack there is an increase in the use of the respiratory muscles as well as in the maintenance of adequate ventilation in daily life activities and the association between head and shoulder position and peak expiratory flow rate has been reported in people with asthma [27].

There seems to be an association between respiratory disorders and neck/shoulder pain and to the best of our knowledge, no study has investigated this association in a prospective design. As the scientific evidence of the importance of respiratory disorders for the develop neck/shoulder pain is scarce and new knowledge may improve clinical management and recommendation for the patients the individual patient, the current area is important to pursue. Our aim was to investigate if respiratory disorders reported are risk factors for reporting troublesome neck/shoulder pain four years later in people with no or occasional neck/shoulder pain at baseline.

Methods

Study design

This prospective cohort study is based on two subsamples from the Stockholm Public Health Cohort (SPHC): one with baseline in 2006 and followed up in year 2010 (SPHC 06/10) (n = 25,173) and one with baseline in 2010 and followed up in year 2014 (SPHC 10/14) (n = 30,730). SPHC is a population-based cohort set up by the Stockholm County Council to collect information about significant contributors to the burden of disease [28]. Details of the data collection and questionnaires are reported elsewhere [28]. The subsample of SPHC 06/10 was used to analyze if reported asthma at baseline was a risk factor, and the subsample SPHC 10/14 was used to analyze if reported COPD at baseline was a risk factor. Information about asthma was not available in the SPHC 10/14, and information about COPD was not available in the SPHC 06/10. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden (2015/1204–32).

Study population

The flow of study persons in this study is displayed in Fig. 1. Eligible for inclusion in the current study was men and women (> 18 years old) who answered the SPHC 06/10 and the 10/14 survey, respectively. To form study populations at risk for troublesome neck/shoulder pain, the inclusion was based on a question in the SPHC survey; “During the previous six months, have you experienced neck or shoulder pain?” (“No”, “Yes, a couple of days in the last six months”, “Yes, a couple of days each month, “Yes, a couple of days each week” and “Yes, everyday”). We included those who answered with either “No” or “Yes, a couple of days last six months” at baseline, here defined as a population with no or occasional neck/shoulder pain. Those with missing data at baseline on the questions on asthma (n = 159) in the SPHC 06/10 and in SPHC 2010/14 on COPD (n = 254) were excluded. As were those with no data on neck/shoulder pain (SPHC 06/10 n = 237, SPHC10/14 n = 399). Thus, our study population was n = 15,155 in SPHC 06/10 and in SPHC10/14 n = 25,273 (Fig. 1).

In SPHC 06/10 n = 959 (6%) reported asthma at baseline and in SPHC 10/14 n = 498 (2%) reported COPD at baseline.

Baseline questionnaire and exposure

Baseline data were elicited with questions regarding demographic characteristics, physical health, psychological health, psychosocial factors, socioeconomic factors, lifestyle, and social factors. These questions were included in the 2006 and 2010 survey, respectively, as reported previously [28].

Exposure

Potential factors of importance for the incidence of troublesome neck/shoulder pain were self-reported asthma and COPD. The questions to measure this were: (i) Do you suffer from asthma? Answered by no/ yes (SPHC 06/10), (ii) Do you suffer from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Answered by no/ yes (SPHC10/14).

Potential confounders

Potential confounding factors were considered in accordance with previous research on risk factors for neck pain, clinical considerations, and availability, after careful discussion about if they instead possibly could be intermediators or colliders. A directed acyclic graph (DAG) was used for this consideration (Fig. 2). Potential confounders reported at baseline in the present study were; age (continuous and dichotomized into < 22, 23–31, 32–41 and > 41); sex (men/women); weight (kg); height (cm); smoking habits (yes, daily); low back pain experienced the previous six months (yes; more than two days); socioeconomic class (unskilled and semiskilled workers, skilled workers, assistant non-manual employee, intermediate non-manual employees, and employed/ self-employed/professional); main physical workload in the past 12 months in the SPCH 06/10 cohort (sedentary, light, moderately heavy, and heavy) and main physical activity load in the past 12 months in the SPHC10/14 (sedentary, light, moderately heavy, and heavy); time spent on household work per week in the SPCH 06/10 (yes > 10 h) and time spent on household work per day in the SPCH 10/14 (yes > 2 h); experience of stress in the SPCH 06/10 (yes, once/month or more), and perceived stress in the SPCH 10/14 (yes, more and much more than usual); country of birth (Sweden/elsewhere); and leisure physical activity level (sedentary < 2 h per week).

Outcome

The outcome was based on questions in the surveys sent four years after the baseline; the 2010 follow-up survey for Asthma and the 2014 follow-up survey for COPD. The outcome was based on the questions on having experienced at least one period of troublesome neck/shoulder pain during the past six months. Participants who answered “yes” to both of the following questions were defined as having had experienced troublesome neck/shoulder pain: “During the past six months, have you felt pain, (at least a couple of days per week) in your neck or shoulder? If so, have these restricted your work capacity or hindered you in daily activities to some degree or to a high degree?”

Statistical analysis

For the analyses of associations between the prognostic factors and the outcome, binomial regression models were used. The results are presented as risk ratios (RR), along with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

Potential confounding factors were identified by directed acyclic graph (DAG) (Fig. 2). The identified potential confounding factors were then added one at a time to the crude regression model. As described by Rothman and Greenland [29], a possible confounding factor that changed the crude RR by 10% or more was considered a confounder and was entered into the final and adjusted model.

Results

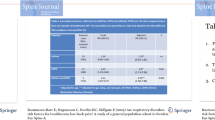

Among people reporting asthma at baseline 2006 (n = 959), 44 persons (5%) reported troublesome neck/shoulder pain in 2010 and among persons reporting COPD at baseline 2010 (n = 498), 35 persons (7%) reported troublesome neck/shoulder pain in 2014. Approximately 50 % of the cohorts were women (SPHC 06/10 51% (n = 7732) and SPHC 10/14 52 % (n = 13,221). Mean age of the cohorts was 49 (SD16) and 50 years (SD18), respectively, and for those suffering from asthma, 45 (SD16) years or for COPD 50 (SD18) years. The demographics of the study population stratified by those who suffered from asthma and COPD at baseline are presented in Table 1.

Age, gender, and smoking emerged as confounding factors for the analyses of asthma and COPD. Adjusted results indicate that those suffering from asthma at baseline 2006 have an increased risk to experience troublesome neck/shoulder pain at follow-up in year 2010 (RR 1.48, 95% CI 1.10–2.01) as do those suffering from COPD at baseline 2010 at follow-up in year 2014 (RR 2.12, 95% CI 1.54–2.93) (Table 2).

Discussion

Our findings show that those who reported no or occasional neck/shoulder pain and reported to suffer from asthma or COPD at baseline, indeed had a higher risk to experience troublesome neck/shoulder at the follow-up four years later. To the best of our knowledge this is the first study investigated this in a longitudinal design. It has previously been reported that an association exists between neck pain and respiratory functions and that interventions to deal with respiratory function might be of value [21]. These findings are presented in studies with a cross-sectional design, thus not specifying the causal effect. A recent review studied factors such as physical activity, sleep disorder and lifestyle factors proposed to associate with pain but was not able to find any sure causal association between the investigated risk factors and neck/shoulder pain [10]. Their results however indicated that exercises enhancing breathing and heart rate were associated with a reduced risk for chronic neck/shoulder pain [10]. It has in addition been reported that people with neck pain may improve pain and pulmonary functions with such exercises [30].

COPD is a disorder that is highly debilitating, and asthma is previously reported to have an impact on health-related quality of life [22, 24, 31]. Some previous studies have in addition reported that respiratory disorders are risk factors for developing troublesome low back pain over time [32, 33] Smith et al. [32] reported that women with respiratory problems developed low back pain over time and vice versa. In addition, a longitudinal cohort study from our research group found that respiratory disorders, both asthma and COPD, were risk factor for developing troublesome low back pain over time [33].

Several neurophysiological reasons behind the interrelationship between neck/shoulder pain and respiratory disorders have been discussed. The diaphragm muscle is reported to play an important role in the muscular respiratory system and in addition a key role in spinal stability and posture [15, 32, 34]. Bordoni et al. [22] discussed the association between a poor functioning diaphragm and COPD and reported that the diaphragm loses its function to contribute to the intra-abdominal pressure in COPD, thus impacting on the spinal stiffness or spinal posture [22]. For those suffering from asthma the physical mechanism seem to be similar as due to the presence of expiratory flow limitation and exercise-induced bronchoconstriction, thus dynamic lung hyperinflation is common [25]. Further, a decline in the inspiratory muscle strength in maximal breathing capacity may lead to a hypertension of the accessory breathing muscles connected to the rib cage and the neck, thus possible increasing the risk of neck pain [35].

Another possible explanation, taking the multi-morbidity perspective into consideration is the association between a sedentary lifestyle, respiratory disorders, and pain. People suffering from COPD reportedly have a lower daily activity level compared to healthy [36]. In our analyses we tested for several confounders including a sedentary lifestyle, which however did not emerge as a confounding factor. A recent study investigating comorbidity in chronic conditions with a sedentary behavior, reported that asthma, and chronic lung disease have been found to have an association with disability, mobility and with chronic back and joint pain [37]. Since the proportion of older people is increasing in the population, the study of multi-morbidity of physical disorders is important to decrease personal suffering and the socioeconomic costs and increase quality of life [38].

Strengths and limitations

A strength of the present study is its prospective design in a general population in which the exposures asthma and COPD were measured at baseline and prior to outcome. Several potential confounders were considered. In our analyses of the association between the exposures and the outcome, we adjusted for age, gender, and daily smoking. Even so, we cannot rule out the risk of unmeasured or residual confounding such as medication, ethnicity, lifestyle, and psychological distress and in addition of misclassification of confounding.

We used two subsamples of the Stockholm Public Health Cohort. The reason for this was that there was only question on either of the exposures in the subsamples. A limitation to the present study is that the questions on asthma and COPD were measured with a single question, which may lead to a misclassification of the exposure. However, since we have no reason to believe that a potential misclassification of the exposure is related to the outcome in a prospective cohort study, the most probable would be non-differential misclassification and a potential dilution of the true association between the exposures and the outcome. Another limitation might be the low power in our analyses as we had few exposed cases. Even so, our findings indicate a risk for people exposed to asthma and COPD to develop troublesome neck/shoulder pain at follow-up.

The response rate from baseline 2006 to follow-up 2010 was 73% and for SPHC 10/14 71%. This means in addition that there might be a risk of selection bias. We have no reason to believe though that the proportion that were exposed to asthma or COPD would differ between those who answered and those lost to follow-up. Therefore, we judge the risk of selection bias to be low. However, the generalizability of our results extends only to cohorts considered comparable to ours.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that those with no or occasional neck/shoulder pain and reporting asthma or COPD increase the risk for troublesome neck/shoulder pain over time. This highlights the importance of taking a multi-morbidity perspective into consideration in health care. Future longitudinal studies are needed to confirm our findings.

Data availability

Data may be available on request to https://www.folkhalsoguiden.se/halsa-stockholm/halsa-stockholm---for-forskare/.

References

Hoy DG, Protani M, De R, Buchbinder R (2010) The epidemiology of neck pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 24:783–792

Fejer R, Kyvik KO, Hartvigsen J (2006) The prevalence of neck pain in the world population: a systematic critical review of the literature. Eur Spine J 15:834–848

Holm LW, Bohman T, Lekander M, Magnusson C, Skillgate E (2020) Risk of transition from occasional neck/back pain to long-duration activity limiting neck/back pain: a cohort study on the influence of poor work ability and sleep disturbances in the working population in Stockholm County. BMJ Open 10:e033946

Hoy D, March L, Woolf A, Blyth F, Brooks P, Smith E et al (2014) The global burden of neck pain: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 73:1309–1315

Hurwitz EL, Randhawa K, Yu H, Cote P, Haldeman S (2018) The Global Spine Care Initiative: a summary of the global burden of low back and neck pain studies. Eur Spine J 27:796–801

Grooten WJ, Mulder M, Josephson M, Alfredsson L, Wiktorin C (2007) The influence of work-related exposures on the prognosis of neck/shoulder pain. Eur Spine J 16:2083–2091

Bohman T, Holm LW, Hallqvist J, Pico-Espinosa OJ, Skillgate E (2019) Healthy lifestyle behaviour and risk of long-duration troublesome neck pain among men and women with occasional neck pain: results from the Stockholm public health cohort. BMJ Open 9:e031078

Rasmussen-Barr E, Grooten WJ, Hallqvist J, Holm LW, Skillgate E (2014) Are job strain and sleep disturbances prognostic factors for neck/shoulder/arm pain? A cohort study of a general population of working age in Sweden. BMJ Open 4:e005103

Skillgate E, Pico-Espinosa OJ, Hallqvist J, Bohman T, Holm LW (2017) Healthy lifestyle behavior and risk of long duration troublesome neck pain or low back pain among men and women: results from the Stockholm Public Health Cohort. Clin Epidemiol 9:491–500

Peterson G, Pihlstrom N (2021) Factors associated with neck and shoulder pain: a cross-sectional study among 16,000 adults in five county councils in Sweden. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 22:872

Carroll LJ, Hogg-Johnson S, Cote P, van der Velde G, Holm LW, Carragee EJ et al (2008) Course and prognostic factors for neck pain in workers: results of the bone and joint decade 2000–2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine 33:S93-100

de Miguel-Diez J, Lopez-de-Andres A, Hernandez-Barrera V, Jimenez-Trujillo I, Del Barrio JL, Puente-Maestu L et al (2018) Prevalence of pain in COPD patients and associated factors: report from a population-based study. Clin J Pain 34:787–794

Fuentes-Alonso M, Lopez-de-Andres A, Palacios-Cena D, Jimenez-Garcia R, Lopez-Herranz M, Hernandez-Barrera V et al (2020) COPD is associated with higher prevalence of back pain: results of a population-based case-control study, 2017. J Pain Res 13:2763–2773

Bentsen SB, Holm AM, Christensen VL, Henriksen AH, Smastuen MC, Rustoen T (2020) Changes in and predictors of pain and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med 171:106116

Hodges PW, Gandevia SC (2000) Changes in intra-abdominal pressure during postural and respiratory activation of the human diaphragm. J Appl Physiol 89:967–976

Hodges P, Kaigle Holm A, Holm S, Ekstrom L, Cresswell A, Hansson T et al (2003) Intervertebral stiffness of the spine is increased by evoked contraction of transversus abdominis and the diaphragm: in vivo porcine studies. Spine 28:2594–2601

Dimitriadis Z, Kapreli E, Strimpakos N, Oldham J (2013) Respiratory weakness in patients with chronic neck pain. Man Ther 18:248–253

Dimitriadis Z, Kapreli E, Strimpakos N, Oldham J (2016) Respiratory dysfunction in patients with chronic neck pain: what is the current evidence? J Bodyw Mov Ther 20:704–714

Kapreli E, Vourazanis E, Billis E, Oldham JA, Strimpakos N (2009) Respiratory dysfunction in chronic neck pain patients. A pilot study Cephalalgia 29:701–710

Wirth B, Amstalden M, Perk M, Boutellier U, Humphreys BK (2014) Respiratory dysfunction in patients with chronic neck pain - influence of thoracic spine and chest mobility. Man Ther 19:440–444

Kahlaee AH, Ghamkhar L, Arab AM (2017) The Association Between Neck Pain and Pulmonary Function: a Systematic Review. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 96:203–210

Bordoni B, Marelli F, Morabito B, Sacconi B, Caiazzo P, Castagna R (2018) Low back pain and gastroesophageal reflux in patients with COPD: the disease in the breath. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 13:325–334

Westerik JA, Metting EI, van Boven JF, Tiersma W, Kocks JW, Schermer TR (2017) Associations between chronic comorbidity and exacerbation risk in primary care patients with COPD. Respir Res 18(1):31

Chen YW, Camp PG, Coxson HO, Road JD, Guenette JA, Hunt MA et al (2017) Comorbidities that cause pain and the contributors to pain in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 98:1535–1543

Shei RJ, Paris HL, Wilhite DP, Chapman RF, Mickleborough TD (2016) The role of inspiratory muscle training in the management of asthma and exercise-induced bronchoconstriction. Phys Sportsmed 44:327–334

Lunardi AC, Marques da Silva CC, Rodrigues Mendes FA, Marques AP, Stelmach R, FernandesCarvalho CR (2011) Musculoskeletal dysfunction and pain in adults with asthma. J Asthma 48:105–110

Robles-Ribeiro PG, Ribeiro M, Lianza S (2005) Relationship between peak expiratory flow rate and shoulders posture in healthy individuals and moderate to severe asthmatic patients. J Asthma 42(9):783–786

Svensson AC, Fredlund P, Laflamme L, Hallqvist J, Alfredsson L, Ekbom A et al (2013) Cohort profile: the stockholm public health cohort. Int J Epidemiol 42:1263–1272

Rothman KJ, Greenland S (2008) Introduction to stratified analysis. 3rd, edn. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams&Williams, Philadelphia

Dareh-Deh HR, Hadadnezhad M, Letafatkar A, Peolsson A (2022) Therapeutic routine with respiratory exercises improves posture, muscle activity, and respiratory pattern of patients with neck pain: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 12:4149

Hernandez G, Dima AL, Pont A, Garin O, Marti-Pastor M, Alonso J et al (2018) Impact of asthma on women and men: comparison with the general population using the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire. PLoS ONE 13:e0202624

Smith MD, Russell A, Hodges PW (2014) The relationship between incontinence, breathing disorders, gastrointestinal symptoms, and back pain in women: a longitudinal cohort study. Clin J Pain 30:162–167

Rasmussen-Barr E, Magnusson C, Nordin M, Skillgate E (2019) Are respiratory disorders risk factors for troublesome low-back pain? A study of a general population cohort in Sweden. Eur Spine J 28:2502–2509

Hodges PW, Gandevia SC, Richardson CA (1997) Contractions of specific abdominal muscles in postural tasks are affected by respiratory maneuvers. J Appl Physiol 83:753–760

Hellebrandova L, Chlumsky J, Vostatek P, Novak D, Ryznarova Z, Bunc V (2016) Airflow limitation is accompanied by diaphragm dysfunction. Physiol Res 65:469–479

Vorrink SN, Kort HS, Troosters T, Lammers JW (2011) Level of daily physical activity in individuals with COPD compared with healthy controls. Respir Res 12:33

Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, Koyanagi A (2017) Physical chronic conditions, multimorbidity and sedentary behavior amongst middle-aged and older adults in six low- and middle-income countries. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 14:147

Picco L, Achilla E, Abdin E, Chong SA, Vaingankar JA, McCrone P et al (2016) Economic burden of multimorbidity among older adults: impact on healthcare and societal costs. BMC Health Serv Res 16:173

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute. The Stockholm Public Health Cohort was financed by Stockholm county council

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, and analysis were performed by ERB and ES. The first draft of the manuscript was written by ERB and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by Stockholm’s Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics and conformed to the declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rasmussen-Barr, E., Nordin, M. & Skillgate, E. Are respiratory disorders risk factors for troublesome neck/shoulder pain? A study of a general population cohort in Sweden. Eur Spine J 32, 659–666 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-022-07509-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-022-07509-z