Abstract

Purpose

To validate the AO Spine Subaxial Injury Classification System with participants of various experience levels, subspecialties, and geographic regions.

Methods

A live webinar was organized in 2020 for validation of the AO Spine Subaxial Injury Classification System. The validation consisted of 41 unique subaxial cervical spine injuries with associated computed tomography scans and key images. Intraobserver reproducibility and interobserver reliability of the AO Spine Subaxial Injury Classification System were calculated for injury morphology, injury subtype, and facet injury. The reliability and reproducibility of the classification system were categorized as slight (ƙ = 0–0.20), fair (ƙ = 0.21–0.40), moderate (ƙ = 0.41–0.60), substantial (ƙ = 0.61–0.80), or excellent (ƙ = > 0.80) as determined by the Landis and Koch classification.

Results

A total of 203 AO Spine members participated in the AO Spine Subaxial Injury Classification System validation. The percent of participants accurately classifying each injury was over 90% for fracture morphology and fracture subtype on both assessments. The interobserver reliability for fracture morphology was excellent (ƙ = 0.87), while fracture subtype (ƙ = 0.80) and facet injury were substantial (ƙ = 0.74). The intraobserver reproducibility for fracture morphology and subtype were excellent (ƙ = 0.85, 0.88, respectively), while reproducibility for facet injuries was substantial (ƙ = 0.76).

Conclusion

The AO Spine Subaxial Injury Classification System demonstrated excellent interobserver reliability and intraobserver reproducibility for fracture morphology, substantial reliability and reproducibility for facet injuries, and excellent reproducibility with substantial reliability for injury subtype.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The AO Spine Subaxial Injury Classification System was designed as a potential tool to help guide management of traumatic subaxial cervical spine injuries. Although subaxial spine injury classifications have existed since the 1970s, they have predominantly relied on anatomic descriptions of injury mechanisms resulting in limited clinical utility [1,2,3]. Furthermore, previous classifications designed to help guide injury management have failed to gain global adoption secondary to poor reliability [4].

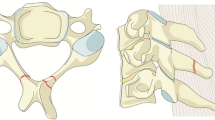

The AO Spine Subaxial Injury Classification System was therefore developed with the goal of prognosticating injury severity and creating a classification with good interobserver reliability and intraobserver reproducibility. To accomplish this, the classification system groups traumatic subaxial cervical spine lesions based on their morphology into A (stable—compression), B (potentially unstable—tension band), and C (unstable—translational) type injuries and includes a classification system of associated facet joint injuries. Morphologic injury types are further subdivided hierarchically into subtypes based on stability and injury severity [5]. In this manner, AO Spine created a concise yet comprehensive injury classification system with previous validation studies by the AO Spine Knowledge Forum Trauma group demonstrating substantial interobserver reliability and intraobserver reproducibility [6]. However, large-scale studies demonstrating the high reliability and reproducibility of the classification system are necessary.

A number of previous studies have aimed at validating subaxial cervical spine injury classifications, but they routinely rely on a small subset of validation members [7, 8]. The utilization of large study groups or international spine organizations is one method to increase the generalizability of fracture classifications, but utilization of these groups has been infrequently reported in the cervical spine literature [9]. Further, no previous study has attempted to validate a subaxial cervical spine fracture classification, while including hundreds of validation members. Therefore, the primary goal of the study was to determine the reliability and reproducibility of the AO Spine Subaxial Injury Classification System via an open call to all participating AO Spine members.

Methods

A live webinar conference was hosted for validation of the AO Spine Subaxial Injury Classification System in 2020. All AO Spine members were invited to participate. Prior to participation, each member attended a live tutorial video and training session directed by one of the creators of the fracture classification. The conference was conducted in English. In this validation, 203 AO Spine members from six different geographic regions of the world (North America, Central and South America, Europe, Africa, Asia and the Pacific, and the Middle East) elected to participate in reviewing computed tomography (CT) videos of 41 distinct subaxial cervical spine injuries. The CT videos consisted of high-resolution sagittal, axial, and coronal videos. Each CT had a viewing range limited to the area of injury. At the same time, each participant was able to view key images of the injury. The videos were presented to the validation members in a randomized order (assessment 1).

Each validation member was tasked with classification of each subaxial cervical spine injury based on the AO Spine Subaxial Injury Classification System, which included injury morphology (A, B, C), injury subtype (A1, A2, B1, etc.), and presence of a facet injury (Fig. 1). After 3 weeks, each participant attended a second live webinar to evaluate the same CT videos (with a new randomized order) and re-classify them (assessment 2). All answers were recorded in an online survey. Demographic data including nationality, surgical subspecialty (orthopedic spine, neurosurgery, or other), and years of experience (< 5, 5–10, 11–20, and > 20) were recorded.

Statistical analysis

A chi-square test was used to evaluate significant differences in the demographic data. Agreement percentages were used to compare the validation member’s classification grade to the “gold standard,” defined by a panel of expert spine surgeons and traumatologists who came to unanimous agreement on the classification of the injury. Cohen’s Kappa (ƙ) statistic was used to assess the reproducibility and reliability of the injury morphology (A, B, or C), injury subtype (A1, A2, A3, etc.), and facet injury (F1, F2, F3, or F4) classification between independent observers (interobserver reliability) and the reproducibility of the injury classification over two assessments (intraobserver reproducibility). The ƙ coefficients were interpreted using the Landis and Koch grading system [10]. A ƙ coefficient of less than 0.2 was defined as slight, between 0.21 and 0.4 as fair, between 0.41 and 0.6 as moderate, between 0.61 and 0.8 as substantial, and greater than 0.8 as excellent reliability or reproducibility.

Results

A total of 203 validation members elected to participate in the AO Spine Subaxial Injury Classification System. A significantly greater proportion of validation members lived in Europe (40%) and Asia (24.6%) with the remaining from Central or South America (16.7%), North America (8.9%), the Middle East (7.4%), and Africa (2.5%) (p < 0.001). Most validation members were orthopedic surgeons (60.6%) or neurosurgeons (36.9%) with only five members identifying as “other” physicians (2.5%) (p < 0.001). The “other” group consisted of residents and radiologists (Table 1).

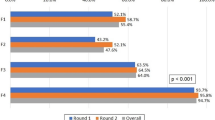

Percent agreement with gold standard

Percent agreement for fracture morphology on assessment 1 (AS1) and assessment 2 (AS2) was 95.4 and 94.7%, respectively. Percent agreement for fracture subtype (AS1: 91.7%, AS2: 90.6%) was lower than the percent agreement for fracture morphology, but similar to the percent agreement for facet injury (AS1: 88.6%, AS2: 91.3%). Additionally, the validation members had minimal variability in correctly identifying each fracture morphology [range, 87.2–97.3%], fracture subtype [range, 78.4–95.6%], and facet injury [range, 86.3–93.0%] (Table 2).

Interobserver reliability

The fracture morphology interobserver reliability (AS1: ƙ = 0.86, AS2: ƙ = 0.87) was excellent. The fracture subtype interobserver reliability (AS1: ƙ = 0.84, AS2: ƙ = 0.80) was excellent on assessment 1, but only substantial on assessment 2. The facet injury classification was substantial on both assessments (AS1: ƙ = 0.67, AS2: ƙ = 0.74) (Table 3).

We subsequently reclassified the interobserver reliability based on surgeon experience, surgical subspecialty, and geographic region to determine if a surgeon’s region of practice, surgical specialty, or experience level resulted in variability in the interobserver reliability of the injury classification. Surgeon experience did not affect interobserver reliability for fracture morphology [range, AS1: 0.83–0.89, AS2: 0.79–0.86], fracture subtype [range, AS1: 0.81–0.86, AS2: 0.76–0.84], or facet injury [range, AS1: 0.67–0.73, AS2: 0.73–0.83]. When grouping by geographic region, larger ranges in interobserver reliability were identified. Fracture morphology [range, AS1: 0.76–0.93, AS2: 0.73–0.89], fracture subtype [range, AS1: 0.75–0.89, AS2: 0.71–0.84], and facet injury [range, AS1: 0.61–0.76, AS2: 0.70–0.90] identified small variations in interobserver reliability between surgeons practicing in different regions of the world (Table 4).

Intraobserver reproducibility

Intraobserver reproducibility for fracture morphology (Type A, B, and C) and fracture subtype (A1-C) was excellent (ƙ = 0.85 and 0.88, respectively), while intraobserver reproducibility for facet injuries (F1-F4) was substantial (ƙ = 0.76) (Table 5).

Similar to the interobserver reliability, intraobserver reproducibility was reclassified based on surgeon experience, surgical subspecialty, and geographic region to determine if these factors influenced reproducibility. Although surgeons with 11–20 years’ experience had slightly higher intraobserver reproducibility in fracture morphology (ƙ = 0.91), fracture subtype (ƙ = 0.87), and facet injury (ƙ = 0.80), the range of the reproducibility based on years of surgical experience was quite low for injury morphology [range, 0.86–0.91], injury subtype [range, 0.83–0.87], and facet injury [range, 0.74–0.80]. There was a similar low variability in intraobserver reproducibility based on surgical subspecialty for fracture morphology (ortho ƙ: 0.89, neuro ƙ: 0.85), subtype (ortho ƙ: 0.85, neuro ƙ: 0.83), and facet injury (ortho ƙ: 0.77, neuro ƙ: 0.73). Further, geographic regions had minimal effect on the reproducibility of identifying injury morphology [range, 0.83–0.91], injury subtype [range, 0.77–0.86], or facet injury [range, 0.73–0.80] (Table 6).

Discussion

The international validation of the AO Spine Subaxial Injury Classification System resulted in classification accuracy of greater than 90% for fracture morphology and fracture subtype on both assessments and demonstrated excellent interobserver reliability and intraobserver reproducibility for fracture morphology, substantial to excellent reliability and reproducibility for fracture subtypes, and substantial reliability and reproducibility for facet injuries. Further, each fracture morphology type (A, B, and C), fracture subtype (A1, B1, C1, etc.) and facet injury type (F1, F2, F3, and F4) had at minimum substantial reliability and reproducibility indicating the system may be universally applied across all subaxial cervical spine injuries. Overall, the results from this international validation study support the utilization of the AO Spine Subaxial Injury Classification System as a tool to communicate subaxial cervical spine injury patterns on a global scale.

The first study to validate the AO Spine Subaxial Injury Classification System was a pilot study that consisted of ten AO Spine Knowledge Forum Trauma members [6]. Their validation study demonstrated the classification had substantial interobserver reliability for injury subtypes (ƙ = 0.64) and injury morphology (ƙ = 0.65) with substantial intraobserver reproducibility for injury morphology (ƙ = 0.77) and injury subtype (ƙ = 0.75) [6]. The AO Spine pilot study combined facet injuries into fracture morphology (A, B, C, and F) and injury subtypes (A1, B1, C1, F1, etc.) making a direct comparison between the international validation study and the pilot study groups difficult. However, when comparing the AO Spine pilot group’s facet injury interobserver reliability (ƙ = 0.66) to the international validation group’s facet injury reliability (AS1: 0.67, AS2: 0.74) both validation groups had a similar substantial reliability. It can also be reasonably assumed that the AO Spine pilot study had similar intraobserver reproducibility (ƙ = 0.75) compared to the international validation after accounting for the separation of fracture morphology reproducibility (ƙ = 0.85) and facet injury reproducibility (ƙ = 0.76).6 Given the disparate injury morphology reliability between the international group and AO Spine pilot study group, it is unlikely inclusion of facet injuries alone accounted for the large gap in reliability (ƙ = 0.87 vs. 0.65, respectively). While substantial, the reproducibility for facet fracture classification remains lower than that of fracture subtype and morphology. This is likely secondary to difficulties distinguishing between F1 and F2 which are commonly misdiagnosed for one another. Reproducibility would likely improve with CT scan imaging with 1 mm cuts [11].

A couple of reasons may explain why the international validation results had a higher injury morphology reliability when compared to the pilot study. First, the international validation group had 203 participants, compared to the AO Spine pilot study that had 10 participants. This improves the margin of error for a participant who has difficulty applying the classification to cervical spine injuries. Perhaps more importantly, the classification system was available for global use five years prior to the international validation study, giving participants time to utilize the classification system in their spine practice before participating in the international validation. Even though our results suggest there is no correlation between surgeon experience and improved AO Spine Subaxial Injury Classification System reliability or reproducibility, no study has examined if increased application of the classification to cervical spine injuries improves a participants accuracy. Of note, no previous study has found a correlation between surgeon experience and the reliability and reproducibility of different AO Spine classifications [12, 13].

A neurosurgery and orthopedic spine attending and three neurosurgery residents performed a separate independent validation of the AO Spine Subaxial Injury Classification System [14]. The intraobserver reproducibility for injury morphology was excellent for both attending spine surgeons (ƙ = 0.86 and 0.95, respectively), and substantial for residents (ƙ = 0.66–0.75) [13]. This held true for injury subtypes with spine surgeons demonstrating excellent reproducibility (ƙ = 0.80 and 0.93, respectively), and residents demonstrating substantial reproducibility (ƙ = 0.63–0.67). When evaluating injury morphology and injury subtype reliability, kappa coefficients ranged from moderate (morphology: ƙ = 0.52 vs. subtype: ƙ = 0.51) on assessment 1 to substantial (morphology: ƙ = 0.63 vs. subtype: ƙ = 0.60) on assessment 2 [14]. The contrast in injury morphology reliability between neurosurgery residents and attending surgeons suggests additional use of the classification may improve its accuracy and the importance of clinical experience in understanding nuanced spinal anatomy and fracture patterns, but future studies are required to confirm this finding.

The AO Spine Latin America Trauma Study group also validated the reliability of facet injuries based on the AO Spine Subaxial Injury Classification System and found surgeons practicing in South America compared to Central America, neurosurgeons compared to orthopedic spine surgeons, and surgeons with 5–10 years’ experience had a greater classification accuracy based on univariate analysis [15]. However, on multivariate analysis only South America region remained significant, while hospital type became significant [15]. Although our study identified an increase in orthopedic spine specialists participating in the webinar, both neurosurgeons and orthopedic spine surgeons had excellent interobserver reliability and intraobserver reproducibility for fracture morphology and subtype, with substantial facet injury interobserver reliability and intraobserver reproducibility. Further, there was minimal variation in intraobserver reproducibility and interobserver reliability based on geographic region. This is consistent with literature evaluating previous AO Spine fracture classification systems in which geographic region did not account for any significant variation in the radiographic classification of thoracolumbar fractures [13].

Limitations were present during this study, which require discussion. A previous iteration of this study was attempted in 2018 with the intention to validate the AO Spine Subaxial Injury Classification System on an international scale. However, the disappointing validation outcomes resulted in methodological design alterations and subsequent re-validation of the classification system in 2020. Although discussed in a separate manuscript, the improvement in validation methodology likely accounted for the substantial to excellent reliability and reproducibility of this classification system. Unique CT videos, which were not previously circulated, were displayed during the 2020 validation. Therefore, any participant who may have had access to the 2018 validation injury films would not obtain an advantage during the 2020 validation. Additionally, due to the utilization of a live webinar to validate the subaxial cervical spine injury classification, participating members were given limited time to classify each injury. This may have led some members who process images at a slower rate, have less experience, or are not fluent in the English language to struggle with completing the validation in a timely fashion, which could have artificially suppressed the reliability and reproducibility of the classification [16,17,18,19]. However, given the substantial to excellent reliability and reproducibility of the classification system on a global level, this was likely of limited significance. While use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) would be helpful to better evaluate the extent of associated soft tissue injuries, AO Spine classification systems utilize CT scans to classify all injuries to minimize inequality gaps present globally that limit access to MRI in some areas [20, 21]. CT scan remains the gold standard for spinal trauma work up, as they are quicker and more accessible than MRIs, with some spine surgeons reporting MRIs taking greater than 24 h to obtain [22].

Conclusion

The AO Spine Subaxial Injury Classification System demonstrated excellent intraobserver reproducibility for fracture morphology and fracture subtype with substantial reproducibility for facet injury. The classification system also had substantial to excellent results when assessing interobserver reliability for fracture morphology, fracture subtype and facet injury. When assessing the reliability and reproducibility of the classification system for each fracture subtype and facet injury variation, the AO Spine Subaxial Injury Classification System demonstrated at minimum substantial reliability and/or reproducibility indicating its global applicability as a classification tool for subaxial cervical spine injuries.

References

Holdsworth F (1970) Fractures, dislocations, and fracture-dislocations of the spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am 52(8):1534–1551

Allen BL Jr, Ferguson RL, Lehmann TR, O’Brien RP (1976) A mechanistic classification of closed, indirect fractures and dislocations of the lower cervical spine. Spine 7(1):1–27. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-198200710-00001

Harris JH Jr, Edeiken-Monroe B, Kopaniky DR (1986) A practical classification of acute cervical spine injuries. Orthop Clin North Am 17(1):15–30

Vaccaro AR, Hulbert RJ, Patel AA et al (2007) The subaxial cervical spine injury classification system: a novel approach to recognize the importance of morphology, neurology, and integrity of the disco-ligamentous complex. Spine 32(21):2365–74. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181557b92

Schroeder GD, Canseco JA, Patel PD et al (2021) Establishing the injury severity of subaxial cervical spine trauma: validating the hierarchical nature of the AO spine subaxial cervical spine injury classification system. Spine 46(10):649–657. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000003873

Vaccaro AR, Koerner JD, Radcliff KE et al (2016) AOSpine subaxial cervical spine injury classification system. Eur Spine J 25(7):2173–2184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-015-3831-3

Lee WJ, Yoon SH, Kim YJ, Kim JY, Park HC, Park CO (2012) Interobserver and intraobserver reliability of sub-axial injury classification and severity scale between radiologist, resident and spine surgeon. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 52(3):200–3. https://doi.org/10.3340/jkns.2012.52.3.200

Silva OT, Sabba MF, Lira HI et al (2016) Evaluation of the reliability and validity of the newer AO Spine subaxial cervical injury classification (C3–C7). J Neurosurg Spine. 25(3):303–8. https://doi.org/10.3171/2016.2.SPINE151039

Kanagaraju V, Yelamarthy PKK, Chhabra HS et al (2019) Reliability of Allen Ferguson classification versus subaxial injury classification and severity scale for subaxial cervical spine injuries: a psychometrics study. Spinal Cord 57(1):26–32. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-018-0182-z

Landis JR, Koch GG (1977) The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33(1):159–174

Cabrera JP, Yurac R, Guiroy A et al (2021) Accuracy and reliability of the AO Spine subaxial cervical spine classification system grading subaxial cervical facet injury morphology. Eur Spine J 30:1607–1614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-021-06837-w

Karamian BA, Schroeder GD, Levy HA et al (2021) The Influence of surgeon experience and subspeciality on the reliability of the AO spine sacral classification system. Spine 46(24):1705–1713. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000004199

Schroeder GD, Kepler CK, Koerner JD et al (2016) Is there a regional difference in morphology interpretation of A3 and A4 fractures among different cultures? J Neurosurg Spine 24(2):332–339. https://doi.org/10.3171/2015.4.SPINE1584

Silva OT, Sabba MF, Lira HI et al (2016) Evaluation of the reliability and validity of the newer AO Spine subaxial cervical injury classification (C3–C7. J Neurosurg Spine 25(3):303–308. https://doi.org/10.3171/2016.2.SPINE151039

Cabrera JP, Yurac R, Guiroy A et al (2021) Accuracy and reliability of the AO Spine subaxial cervical spine classification system grading subaxial cervical facet injury morphology. Eur Spine J 30(6):1607–1614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-021-06837-w

Faber LG, Maurits NM, Lorist MM (2012) Mental fatigue affects visual selective attention. PLoS ONE 7(10):e48073. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0048073

Salthouse TA (1996) The processing-speed theory of adult age differences in cognition. Psychol Rev 103(3):403–428. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.103.3.403

Eckert MA, Keren NI, Roberts DR, Calhoun VD, Harris KC (2010) Age-related changes in processing speed: unique contributions of cerebellar and prefrontal cortex. Front Hum Neurosci 4:10. https://doi.org/10.3389/neuro.09.010.2010

Barrón-Estrada ML, Zatarain-Cabada R, Romero-Polo JA, Monroy JN (2021) Patrony: A mobile application for pattern recognition learning. Educ Inf Technol (Dordr) 8:1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10636-7

Ogbole GI, Adeyomoye AO, Badu-Peprah A et al (2018) Survey of magnetic resonance imaging availability in West Africa. Pan Afr Medical J 30:240. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2018.30.240.14000

Volpi G (2016) Radiography of diagnostic imaging in Latin America. Nucl Medicine Biomed Imaging 1:10–12. https://doi.org/10.15761/nmbi.1000105

Schroeder GD, Canseco JA, Patel PD et al (2020) Establishing the injury severity of subaxial cervical spine trauma validating the hierarchical nature of the AO spine subaxial cervical spine injury classification system. Spine. https://doi.org/10.1097/brs.0000000000003873

Acknowledgements

The authors of the manuscript would like to thank Olesja Hazenbiller for her assistance in developing the methodology and providing support during the validation. We would also like to thank Christian Knoll and Janik Hilse from the AO Innovation Translation Center for their support with the statistical analysis, developing the methodology, and database structure.

AO Spine Validation Participants:

Bruno Lourenco Costa, Martin Estefan, Ahmed Dawoud, Ariel Kaen, Sung-Joo Yuh, Segundo Fuego, Francisco Mannara, Gunaseelan Ponnusamy, Tarun Suri, Subiiah Jayakumar, Luis Cuchen Rodriguez, Derek Cawley, Amauri Godinho, Johnny Duerinck, Nicola Montemurro, Kubilay Ozdener, Zachary Hickman, Alsammak Wael, Dilip Gopalakrishnan, Bruno Santos, Olga Morillo, Yasunori Sorimachi, Naohisa Miyakoshi, Mahmoud Alkharsawi, Nimrod Rahamimov, Vijay Loya, Peter Loughenbury, Jose Rodrigues, Nanda Ankur, Olger Alarcon, Nishanth Ampar, Kai Sprengel, Macherla Subramaniam, Kyaw Linn, Panchu Subramanian, Georg Osterhoff, Sergey Mlyavykh, Elias Javier Martinez, Uri Hadelsberg, Alvaro Silva, Parmenion Tsitsopoulos, Satyashiva Munjal, Selim Ayhan, Nigel Gummerson, Anna Rienmuller, Joachim Vahl, Gonzalo Perez, Eugene Park, Alvin Pun, Kartigeyan Madhivanan, Andrey Pershin, Bernhard Ullrich, Nasser Khan, Olver Lermen, Hisco Robijn, Nicolas Gonzalez Masanes, Ali Abdel Aziz, Takeshi Aoyama, Norberto Fernandez, Aaron HJills, Hector Roldan, Alessandro Longo, Furuya Takeo, Tomi Kunej, Jain Vaibhav, Juan Delgado-Fernandez, Guillermo Espinosa Hernandez, Alessandro Ramieri, Lingjie Fu, Andrea Redaelli, Jibin Francis, Bernucci Claudio, Ankit Desai, Pedro Bazan, Rui Manilha, Maximo-Alberto Diez-Ulloa, Lady Lozano, Thami Benzakour, John Koerner, Fabricio Medina, Rian Vieira, O. Clark West, Mohammad El-Sharkawi, Christina Cheng, Rodolfo Paez, Sofien Benzarti, Tarek Elhewala, Stipe Corluka, Ahmad Atan, Bruno Santiago, Jamie Wilson, Raghuraj Kundangar, Pragnesh Bhatt, Amit Bhandutia, Slavisa Zagorac, Shyamasunder Nerrkaje, Anton Denisov, Daniela Linhares, Guillermo Ricciardi, Eugen Cezar Popescu, Dave Bharat, Stacey Darwish, Ricky Rasschaert, Arne Mehrkens, Mohammed Faizan, Sunao Tanaka, Aaron Hockley, Aydinli Ufuk, Michel Triffaux, Oleksandr Garashchuk, Dave Dizon, Rory Murphy, Ahmed Alqatub, Kiran Gurung, Martin Tejeda, Rajesh Lakhey, Arun Viswanadha, Oliver Riesenbeck, Daniel Rapetti, Rakesh Singh, Naveenreddy Vallapureddy, Triki Amine, Osmar Moraes, Dalia Ali, Alberto Balestrino, Luis Luna, Lukas Grassner, Eduardo Laos, Rajendra Rao Ramalu, Sara Lener, Gerardo Zambito, Andrew Patterson, Christian Konrads, Mario Ganau, Mahmoud Shoaib, Konstantinos Paterakis, Zaki Amin, Garg Bhavuk, Adetunji Toluse, Zdenek Klezl, Federico Sartor, Ribakd Rioja, Konstantinos Margetis, Paulo Pereira, Nuno Neves, Darko Perovic, Ratko Yurak, Karmacharya Balgopal, Joost Rutges, Jeronimo Milano, Alfredo Figueiredo, Juan Lourido, Salvatore Russo, Chadi Tannoury, David Orosco Falcone, Matias Pereria Duarte, Sathish Muthu, Hector Aceituno, Devi Tokala, Jose Ballesteros Plaza, Luiz dal Oglio da Rocha, Rodrigo Riera, Shah Gyanendra, Zhang Jun, David Suarez-Fernandez, Ali Oner, Geoffrey Tipper, Ahmad Osundina, Waeel Hamouda, Zacharia Silk, Ignacio Fernandez Bances, Aida Faruk Senan Nur, Anuj Gupta, Saul Murrieta, Francesco Tamburrelli, Miltiadis Georgiopoulos, Amrit Goyal, Sergio Zylbersztejn, Paloma Bas, Deep Sharma, Janardhana Aithala, Sebastian Kornfeld, Sebastian Cruz-Morande, Rehan Hussain, Maria Garcia Pallero, Hideki Nagashima, Hossein Elgafy, Om Patil, Joana Guasque, Ng Bing Wui, Triantafyllos Bouras, Kumar Naresh, Fon-Yih Tsuang, Andreas Morakis, Sebastian Hartmann, Pierre-Pascal Girod, Thomas Reihtmeier, Welege Wimalachandra.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The AO Spine Injury Classification Systems were developed and funded by AO Spine through the AO Spine Knowledge Forum Trauma, a focused group of international spine trauma experts. AO Spine is a clinical division of the AO Foundation, which is an independent medically guided not-for-profit organization. Study support was provided directly through the AO Spine Research Department.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Karamian, B.A., Schroeder, G.D., Lambrechts, M.J. et al. An international validation of the AO spine subaxial injury classification system. Eur Spine J 32, 46–54 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-022-07467-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-022-07467-6