Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to gain new insights into the epidemiologic characteristics of patients with atlas fractures and to retrospectively evaluate complication rates after surgical and non-surgical treatment.

Methods

In a retrospective study, consecutive patients diagnosed with a fracture of the atlas between 01/2008 and 07/2018 were analyzed. Data on epidemiology, concomitant injuries, fracture patterns and complications were obtained by chart and imaging review.

Results

In total, 189 patients (mean age 72 years, SD 19; 57.1% male) were treated. The most frequent trauma mechanism was a low-energy trauma (59.8%). A concomitant injury of the cervical spine was found in 59.8%, a combined C1/C2 injury in 56.6% and a concomitant fracture of the thoraco-lumbar spine in 15.4%. When classified according to Gehweiler, there were: 23.3% type 1, 22.2% type 2, 32.8% type 3, 19.0% type 4 and 1.1% type 5. Treatment of isolated atlas fractures (n = 67) consisted of non-operative management in 67.1%, halo fixation in 6.0% and open surgical treatment in 26.9%. In patients with combined injuries, the therapy was essentially dictated by the concomitant subaxial cervical injuries.

Conclusions

Atlas fractures occurred mainly in elderly people and in the majority of the cases were associated with other injuries of the head and spine. Most atlas fractures were treated conservatively. However, surgical treatment has become a safe and valid option in unstable fracture patterns involving the anterior and posterior arch (type 3) or those involving the articular surfaces (type 4).

Level of evidence

IV (Retrospective cohort study).

Graphic abstract

These slides can be retrieved under Electronic Supplementary Material.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The anatomic particularities of the atlas make its fractures unique compared to other cervical spine elements. It acts as a transitional structure between the occipital bone of the skull and the spine. It articulates with the odontoid process of the second cervical vertebra (axis) and the occiput allowing rotation, flexion, extension and lateral flexion of the head [1].

Twenty-five percent of all craniocervical injuries, 2–13% of all cervical spine injuries and 1–3% of all spinal injuries are represented by fractures of the first vertebra [1]. The main trauma mechanism in atlas fractures is axial loading which affects especially at the back of the head and with deflection of force to the lateral masses [2]. The resulting tension forces acting on the osseous ring of the atlas can result in various fractures, which commonly are described by the classification systems of Jefferson [3] and Gehweiler [4].

Fractures of the atlas are rare and frequently overlooked injuries as patients often show no neurological symptoms or clear evidence in conventional radiographic imaging. They particularly involve two age categories—elderly people with low-energy trauma and younger patients with high-energy trauma like motor vehicle accidents and falls from greater heights [5, 6].

Over the last two decades, demographic aging and advances in computed tomography (CT) technologies have increased the incidence of diagnosed atlas fractures [7]. Resulting therapy options for treatment of C1 fractures have been repeatedly discussed in the literature. Surgical stabilization has become a more established treatment modality in certain fracture patterns because modern implant systems and better intraoperative imaging [8] have changed and broadened the range of indications [9, 10].

Current studies on the epidemiology of atlas fractures and the complications associated with their treatment are missing. Hence, the purpose of this study was to gain new insights into the epidemiologic characteristics of patients with atlas fractures and to retrospectively evaluate complication rates after surgical and non-surgical treatment.

Patients and methods

Patients

This retrospective cohort study was approved by the institutional ethics committee (reference: 302/18-ek). Consecutive patients who were diagnosed with a fracture of the atlas at our Level 1 university trauma center between 01/2008 and 07/2018 were identified through a search of the clinical information system (SAP, Walldorf, Germany). Patients with existing documented objection to research in their chart were excluded.

Data acquisition

In a retrospective chart and database review, information on the patients’ baseline characteristics, the mechanism of trauma and concomitant injuries were documented.

As a standard, posttraumatic CT scans were performed in all patients. On these, the type of fracture was classified according to the system described by Gehweiler [4] (Fig. 1) by two board-certified spine surgeons (US, GO). Information on treatment modality, in-hospital complications and secondary interventions during the whole follow-up was obtained. Infections were reported as either surgical-site infections or systemic infections. Surgical-site infections were determined as wound healing problems treated by antibiotics and/or revision surgery. Systemic infections were defined as conditions with elevated inflammatory blood markers that required antibiotic treatment (as pneumonia, urinary tract infection, etc.)

Gehweiler classification of atlas fractures [4]. Type 1: fractures of the anterior arch (Jefferson II, Landells I). Type 2: fractures of the anterior arch (Jefferson I, Landells I). Type 3: fractures of the anterior and posterior arch (Jefferson III, Landells II). Type 4: fractures of the lateral mass (Jefferson IV, Landells III). Type 5: isolated fractures of the transverse process. J Jefferson, L Landells

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as frequencies (n) with percentages (%) and means with the standard deviation (SD). Post-test analysis was done using SPSS for Windows V25.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). All data are reported as frequencies (n) with percentages (%) and means with the standard deviation (SD).

Nonparametric tests were used for the comparison of differences in means between patients older than 65 years and younger patients, and cross-tables with chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests were used for the comparison of nominal data. The level of significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

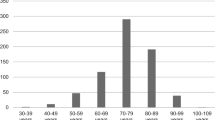

During the observation period of 10 years, 189 patients (mean age 72 years, SD 19, range 6–97 years) were treated with a fracture of the atlas. The majority of the patients (108/189, 57.1%) were of male gender. Leading trauma mechanism was a low-energy trauma (113/189, 59.8%), in three of which this was associated with a metastatic lesion of the first vertebra.

Of 189 atlas fractures included, only 63 were isolated injuries. One or more concomitant injuries to the head and spine were present in 66.7% (Fig. 2), a concomitant fracture of the cervical spine (C2–C7) in 59.8%, and at least one fracture of the whole spine (C2–L5) in 64.6%. A concomitant head injury was found in 25.9% of the cases, and in 15/189 patients (7.9%) this included intracranial hemorrhage. Fractures of the occipital condyles were seen in 10/189 cases (5.3%). A combined atlanto-axial fracture was present in 107/189 cases (56.6%), and concomitant fractures of the thoraco-lumbar spine were observed in 23/189 patients (15.4%).

When classified by Gehweiler, 23.3% represented type 1 fractures, 22.2% type 2 fractures, 32.8% type 3 fractures, 19.0% type 4 fractures and 1.1% type 5 fractures (Fig. 3). Two fractures could not be classified: one combination of an anterior arch and a comminuted lateral mass fracture and one transverse split of the whole ring. In one patient, only MRT imaging was available that did not allow for a proper classification.

Fracture pattern distributions according to Gehweiler. Type 1: fractures of the anterior arch (Jefferson II, Landells I). Type 2: fractures of the anterior arch (Jefferson I, Landells I). Type 3: fractures of the anterior and posterior arch (Jefferson III, Landells II). Type 4: fractures of the lateral mass (Jefferson IV, Landells III). Type 5: isolated fractures of the transverse process

Two of the 189 patients were treated in an outpatient setting only. The mean duration of hospitalization was 12 days (SD 10, range 1–77). The average time between trauma and treatment was 4 days (SD 7, range 0–44). In-hospital complications included thromboembolic events in 2/187 patients (1.1%), surgical-site infection (n = 2) or systemic infection (n = 25) in 27/187 patients (14.4%), and delirium in 18/187 patients (9.6%). All-cause 30-day mortality was 12.2% (23/189). Causes of death could not be attributed to the atlas fractures except for three patients with cardiac arrhythmia and/or respiratory failure on admission that might be related to brainstem compression. Seven patients died before treatment could be applied.

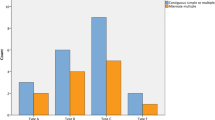

Treatment consisted of non-operative treatment with soft or rigid collars in 82/182 (45.1%), with halo fixation in 13 (7.1%) and with open surgical procedures in 87 patients (47.8%, Table 1). However, in many cases, the indication for surgery was made due to concomitant injuries of the adjacent cervical spine segments. In isolated fractures of the atlas without concomitant injuries to the occipital condyle or C2–C7 that were amenable for treatment (n = 67), non-operative treatment with a soft or rigid collar was performed in 45/67 cases (67.1%), halo fixation in 4/67 (6.0%) and open surgical fixation in 18/67 patients (26.9%, Fig. 4).

Treatment of isolated atlas fractures by fracture pattern (n = 67). Patients with concomitant injuries to the occipital condyle or C2–C7 are excluded. C1 direct: direct open reduction and internal fixation of the atlas (anterior and posterior approaches). C1/2 fusion: anterior or posterior fusion C1–C2. C0–C2+: posterior fusion from occiput to C2 and beyond

Secondary interventions during the whole follow-up were necessary in 14/189 patients (7.4%); this included one patient who had a re-fracture of the atlas after a second fall, three patients with non-operative treatment that required secondary stabilization with halo fixation, and two patients with implant removal after more than a year, three patients with halo fixation that required secondary C1/2 fusion. Revision surgery of open fixation was necessary in 5/87 (5.7%) cases; this included surgical-site infection in two and loss of reduction in three cases.

Patients older than 65 years were more likely to be female (p < 0.001, Table 2), sustain a low-energy trauma (p < 0.001) and to suffer of in-hospital complications including death (p = 0.004). In addition, patients older than 65 years were more likely to present with fractures Gehweiler type 1 and 2 while younger patients more frequently had fractures type 3 and 4 (p = 0.008). Younger patients had more concomitant fractures of the occipital condyle (p = 0.028) and elderly patients had more combined C1/C2 fractures (p < 0.001).

Patients who were treated non-operatively had a shorter hospital stay (p = 0.002, Table 3) but were more likely to die during the hospitalization. The difference in hospital stay was still significant when comparing only patients who did not die during their initial hospitalization (non-operative: 10 days, SD 10; operative: 14 days, SD 11; p < 0.001). The occurrence of in-hospital infections (p = 0.836), thromboembolic events (p = 1.0) and delirium (p = 0.806) was not different between operatively and non-operatively treated patients. Patients with a high-energy trauma (p = 0.028) and patients with a concomitant fracture of C2 (p < 0.001) were more likely to receive operative treatment.

Discussion

This study presents epidemiologic data on atlas fractures over an observation period of 10 years.

It was found that the majority of patients with atlas fractures are male and that most cases occurred in the elderly population with a mean age of 72 years. This is in line with findings of previous epidemiologic studies on this topic that confirm a higher incidence of C1 fractures among the elderly [5, 11].

The main cause of trauma was a low-energy trauma which typically occurs in the older population where frequent falls combined with degenerative changes and reduced mobility of the lower cervical spine increase the risk of upper cervical fractures.

Only 33% of all atlas fractures were isolated injuries. About two-thirds of the cases were diagnosed with one or more concomitant head and spine injuries, and especially combined atlanto-axial fractures were seen in more than half of the patients. Previous studies have shown that atlas fractures rarely occur in isolation but often in association with other injuries of the spine [12, 13]. The combination of C1 and C2 injuries has been reported for 40–44% of the patients with atlas fractures in the literature [1, 9]. This was confirmed by findings of the present study, even though the incidence of concomitant injuries was noticeably higher compared to previously published results. Possible explanations include that CT imaging increasingly has become a standard diagnostic procedure for injuries of the cervical spine. The high percentage of concomitant intracranial bleedings may also be a result of the increased prevalence of oral anticoagulants in elderly patients. In fact, the high co-prevalence of occiput and C2 fractures and intracranial bleedings found in this series of cohort with atlas fractures strongly suggest a low threshold for performing CT imaging in these cases.

The distribution of fracture patterns according to Gehweiler showed that the majority of the injuries are type 3 fractures, followed by type 1 and 2, and then less frequently type 4 articular fractures. The transverse process fractures (Gehweiler 5) were found to be a rarity, which may be rooted in the rather subtle clinical symptoms they cause. This distribution of fracture patterns is consistent with data from previous studies [14, 15].

While isolated atlas fractures of type 1, 2 and 5 were preferably managed non-operatively, type 3 fractures and type 4 fractures were more often treated surgically in our study. This is in congruence with current treatment guidelines [16]. Despite inconsistent recommendations in the literature, fractures Gehweiler type 1, 2 and 5 are consistently being treated with conservative therapy.

Likewise, most studies report similar rates of surgical treatment of unstable type 3 (“Jefferson”) fractures [9, 14]. In contrast to the literature, however, almost every fourth Gehweiler 4 fracture in our population was treated operatively. The literature mainly recommends conservative treatment for isolated fractures of the lateral masses [10]. However, recent studies observed frequently a lateral displacement of the lateral mass fragments associated with subluxation of the occipital condyle resulting in neck pain, head malposition and impaired head rotation [17]. Hence, some guidelines advocate for surgery in Gehweiler 4 fractures with joint incongruency [9, 18]. In this context, it must be noted that the decision for and the type of surgery was frequently made based on concomitant injuries of the adjacent cervical spine segments.

The in-hospital complications observed in this study were in the range of what is known from other case series [1, 10]. Nosocomial infections as well as the development of a delirium must be considered as high-risk complications after surgery of elderly patients. In our cohort, patients who were treated non-operatively had a shorter hospital stay but were more likely to die during the hospitalization. Hence, as in other studies, the impact of a surgical intervention on the occurrence of complications was minor, as most part in-hospital complications were determined by the prevalence of preexisting comorbidities [13, 19].

The limitations of this study are associated with the retrospective design and the lack of follow-up examinations. It is difficult to assess post hoc what influence the patients’ illness had in some cases on the decision for or against surgical treatment. It might be that patients with estimated higher perioperative morbidity were frequently treated non-operatively even though the fracture pattern itself would have suggested surgery. An indication for this is the higher in-hospital mortality in the non-operative group. In fact, some patients might have died before surgery was possible.

We also did not perform a radiographic assessment of fracture union rates. The lack of complications or nonunions does not necessarily mean that these patients had good functional outcomes. The definition of “low-energy trauma” used in this retrospective analysis is very broad. Especially in elderly patients, it can often be difficult to precisely assess how deep and with how much energy the patient fell. This is a problem also known from thoraco-lumbar fractures in elderly patients.

Even though a large sample in total, the number of patients in each fracture pattern group did not allow statistic comparisons of operative versus non-operative treatment across single fracture types. Thus, the findings of this study cannot be used to support operative versus non-operative treatment for specific fracture patterns of the atlas. Future prospective comparative studies need to further investigate the potential benefit of operative versus non-operative treatment of atlas fractures in elderly patients.

Conclusion

It was found that atlas fractures occurred mainly in elderly people and in the majority of the cases were associated with other injuries of the head and spine. Most atlas fractures can be treated conservatively. However, surgical treatment has become a safe and valid option in unstable fracture patterns involving the anterior and posterior arch (type 3) or those involving the articular surfaces (type 4). Both detecting concomitant injuries and assessing instability and joint incongruence may be facilitated by the regular use of CT imaging in these patients.

References

Kakarla UK, Chang SW, Theodore N, Sonntag VKH (2010) Atlas fractures. Neurosurgery 66(3 Suppl):60–67. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.NEU.0000366108.02499.8F

Ryba L, Cienciala J, Chaloupka R, Repko M, Vyskočil R (2016) Poranění horní krční páteře (Injury of upper cervical spine). Soud Lek 61(2):20–25

Jefferson G (1919) Fracture of the atlas vertebra. Report of four cases, and a review of those previously recorded. Br J Surg 7(27):407–422. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800072713

Gehweiler JA, Duff DE, Martinez S, Miller MD, Clark WM (1976) Fractures of the atlas vertebra. Skelet Radiol 1(2):97–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00347414

Watanabe M, Sakai D, Yamamoto Y, Sato M, Mochida J (2010) Upper cervical spine injuries: age-specific clinical features. J Orthop Sci 15(4):485–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00776-010-1493-x

Jubert P, Lonjon G, Garreau de Loubresse C (2013) Complications of upper cervical spine trauma in elderly subjects. A systematic review of the literature. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res OTSR 99(6 Suppl):S301–S312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otsr.2013.07.007

Smith RM, Bhandutia AK, Jauregui JJ, Shasti M, Ludwig SC (2018) Atlas fractures: diagnosis, current treatment recommendations, and implications for elderly patients. Clin Spine Surg 31(7):278–284. https://doi.org/10.1097/BSD.0000000000000631

Baumert B, Blautzik J, Körner M, Reiser M, Linsenmaier U (2008) Aktuelle bildgebende Diagnostik der Wirbelsäulenerkrankungen (Advanced imaging of spine disease). Der Chirurg; Zeitschrift fur alle Gebiete der operativen Medizen 79(10):906–917. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00104-008-1516-8

Kandziora F, Scholz M, Pingel A, Schleicher P, Yildiz U, Kluger P, Pumberger M, Korge A, Schnake KJ (2018) Treatment of atlas fractures: recommendations of the spine section of the german society for orthopaedics and trauma (DGOU). Glob Spine J 8(2 Suppl):5S–11S. https://doi.org/10.1177/2192568217726304

Mead LB, Millhouse PW, Krystal J, Vaccaro AR (2016) C1 fractures: a review of diagnoses, management options, and outcomes. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 9(3):255–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-016-9356-5

Matthiessen C, Robinson Y (2015) Epidemiology of atlas fractures—a national registry-based cohort study of 1537 cases. Spine J 15(11):2332–2337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2015.06.052

Kayser R, Weber U, Heyde CE (2006) Verletzungen des kraniozervikalen Ubergangs (Injuries to the craniocervical junction). Der Orthopade 35(3):244–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00132-005-0920-8

Schären S, Jeanneret B (1999) Atlas fractures. Der Orthopade 28(5):385–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00003622

Kandziora F, Chapman JR, Vaccaro AR, Schroeder GD, Scholz M (2017) Atlas fractures and atlas osteosynthesis: a comprehensive narrative review. J Orthop Trauma 31(Suppl 4):S81–S89. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0000000000000942

Kandziora F, Schnake K, Hoffmann R (2010) Verletzungen der oberen halswirbelsäule. Teil 2: knöcherne verletzungen (Injuries to the upper cervical spine. Part 2: osseous injuries). Der Unfallchirurg 113(12):1023–1039. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00113-010-1896-3

Scholz M, Schleicher P, Kandziora F, Badke A, Dreimann M, Gebhard H, Gercek E, Gonschorek O, Hartensuer R, Jarvers J-SG, Katscher S, Kobbe P, Koepp H, Korge A, Matschke S, Mörk S, Müller CW, Osterhoff G, Pécsi F, Pishnamaz M, Reinhold M, Schmeiser G, Schnake KJ, Schneider K, Spiegl UJA, Ullrich B (2018) Empfehlungen zur Diagnostik und Therapie oberer Halswirbelsäulenverletzungen: axisringfrakturen (Recommendations for Diagnosis and Treatment of Fractures of the Ring of Axis). Zeitschrift fur Orthopadie und Unfallchirurgie 156(6):662–671. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0620-9170

Keskil S, Göksel M, Yüksel U (2016) Unilateral lag-screw technique for an isolated anterior 1/4 atlas fracture. J Craniovertebral Junction Spine 7(1):50–54. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-8237.176625

Schleicher P, Scholz M, Kandziora F, Badke A, Dreimann M, Gebhard HW, Gercek E, Gonschorek O, Hartensuer R, Jarvers J-SG, Katscher S, Kobbe P, Koepp H, Matschke S, Mörk S, Müller CW, Osterhoff G, Pécsi F, Pishnamaz M, Reinhold M, Schmeiser G, Schnake KJ, Schneider K, Spiegl UJA, Ullrich B (2019) Empfehlungen zur Diagnostik und Therapie oberer Halswirbelsäulenverletzungen: Atlasfrakturen (Recommendations for the Diagnostic Testing and Therapy of Atlas Fractures). Z Orthop Unfall 157(5):566–573. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0809-5765

Delcourt T, Bégué T, Saintyves G, Mebtouche N, Cottin P (2015) Management of upper cervical spine fractures in elderly patients: current trends and outcomes. Injury 46(Suppl 1):S24–S27. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-1383(15)70007-0

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

CEH has received royalties from Medacta Int. GO has given paid lectures for Medtronic and Stryker. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests. There was no external funding for this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fiedler, N., Spiegl, U.J.A., Jarvers, JS. et al. Epidemiology and management of atlas fractures. Eur Spine J 29, 2477–2483 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-020-06317-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-020-06317-7