Abstract

Purpose

In clinical decision-making, it is crucial to discuss the probability of adverse outcomes with the patient. A large proportion of the outcomes are difficult to classify as either failure or success. Consequently, cutoff values in patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) for “failure” and “worsening” are likely to be different from those of “non-success”. The aim of this study was to identify dichotomous cutoffs for failure and worsening, 12 months after surgical treatment for lumbar disc herniation, in a large registry cohort.

Methods

A total of 6840 patients with lumbar disc herniation were operated and followed for 12 months, according to the standard protocol of the Norwegian Registry for Spine Surgery (NORspine). Patients reporting to be unchanged or worse on the Global Perceived Effectiveness (GPE) scale at 12-month follow-up were classified as “failure”, and those considering themselves “worse” or “worse than ever” after surgery were classified as “worsening”. These two dichotomous outcomes were used as anchors in analyses of receiver operating characteristics (ROC) to define cutoffs for failure and worsening on commonly used PROMs, namely, the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), the EuroQuol 5D (EQ-5D), and Numerical Rating Scales (NRS) for back pain and leg pain.

Results

“Failure” after 12 months for each PROM, as an insufficient improvement from baseline, was (sensitivity and specificity): ODI change <13 (0.82, 0.82), ODI% change <33% (0.86, 0.86), ODI final raw score >25 (0.89, 0.81), NRS back-pain change <1.5 (0.74, 0.86), NRS back-pain % change <24 (0.85, 0.81), NRS back-pain final raw score >5.5 (0.81, 0.87), NRS leg-pain change <1.5 (0.81, 0.76), NRS leg-pain % change <39 (0.86, 0.81), NRS leg-pain final raw score >4.5 (0.91, 0.85), EQ-5D change <0.10 (0.76, 0.83), and EQ-5D final raw score >0.63 (0.81, 0.85). Both a final raw score >48 for the ODI and an NRS >7.5 were indicators for “worsening” after 12 months, with acceptable accuracy.

Conclusion

The criteria with the highest accuracy for defining failure and worsening after surgery for lumbar disc herniation were an ODI percentage change score <33% for failure and a 12-month ODI raw score >48. These cutoffs can facilitate shared decision-making among doctors and patients, and improve quality assessment and comparison of clinical outcomes across surgical units. In addition to clinically relevant improvements, we propose that rates of failure and worsening should be included in reporting from clinical trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In spine surgery, several well-validated patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) have been recommended, such as the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) [1], Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) for leg pain and back pain [2], and the EuroQol 5D (EQ-5D) [3]. Still, clinicians are often unfamiliar with their interpretation. In large cohorts, even small and clinically irrelevant PROM changes tend to reach statistical significance [4]. To provide cutoffs on PROM changes that are perceived as meaningful and important by the patients, the “minimal important change” (MIC) has been defined by various methods [5,6,7]. A recent review proposed an MIC cutoff for the ODI of ten points, or 30% improvement from baseline [8]. Several studies have identified MIC cutoffs for the NRS back pain and leg pain from 2 to 2.5 [8, 9]. In addition, cutoffs for substantial clinical improvements, such as “success” after lumbar disc surgery, have been reported both for the ODI (20), NRS back pain (2.5), NRS leg pain (3.5), and EQ-5D (0.3) [9,10,11]. A large proportion of the patients are difficult to classify as either improved, unchanged, or worse after surgery [12]. Consequently, cutoffs on the PROMs for deterioration and “failure” may be different from those of “non-success”. Previously, authors have used various methods and different concepts for defining cutoffs for clinical meaningful improvements [10, 12], resulting in a diversity of recommended threshold values [8, 21, 22]. This makes it even more difficult to disentangle “failure” from constructs developed to identify improvements. There is clearly a grey zone between “failure” and “non-success” [13], “minimal meaningful improvements”, or a “satisfactory symptom state” [14]. Using an external anchor method to define “failure” more accurately could provide more robust definitions of this outcome category [11]. It is, therefore, important to differentiate between “failure” and “non-success”.

The indication for operative treatment of lumbar disc herniation is relative, and the decision to operate must be based on a trade-off between possible benefits, risks, and costs [15]. In clinical trials, focus is generally placed on improvements such as “success rates”. To enhance quality assessment and shared decision-making, it is crucial to consider the other end of the scale and to discuss the possibility of adverse outcomes with the patients. Avoiding inefficient operations may have a greater impact on treatment outcomes, than improving surgical technique [16]. The first step would be to try to define cutoffs for “failure” and “worsening” on the PROMs. When informing the patient about possible outcomes, we think that it is important to differentiate between being unchanged after surgery, which might be an acceptable risk, and actually getting worse, which might be harmful. Previous studies show that larger cohorts are needed to clearly define clinically meaningful thresholds for such outcomes, especially for worsening [17, 18].

The Norwegian Registry for Spine Surgery (NorSpine) collects clinical data (PROMs) on the majority of patients operated for lumbar disc herniation in Norway. Its purpose is to evaluate treatment outcomes from the “real life” of daily clinical practice and use this information to improve the quality of the health services [19, 20]. The aim of this study was to estimate the most accurate cutoffs for both failure and worsening after surgical treatment of lumbar disc herniation, using data from the large registry cohort of the NORspine. Such benchmark criteria could be used for calculating sample size in research and facilitate shared decision-making among doctors and patients, clinical audit, and comparisons of outcomes across surgical units.

Methods

Patient population and data collection

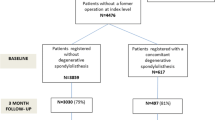

6840 patients operated for lumbar disc herniation between January 1st, 2007 and February 28th, 2014 were followed for 12 months, according to the standard NORspine protocol. The NORspine is a comprehensive clinical registry for quality control and research. Both emergency and elective cases are registered. We included all patients who were treated for lumbar disc herniation with lumbar discectomy and/or herniectomy. Fusion procedures or laminectomy with removal of midline structures were not included. Table 1 describes the exclusion criteria in the current study. This study comprises 38 of 40 (95%) Norwegian private and public centers, performing surgery for degenerative spinal disorders. The inclusion rate for lumbar disc herniation is currently about 65% in the NORspine.

Informed consent was obtained from all patients and participation was neither mandatory, nor required to gain access to healthcare. According to Norwegian legislation, patients over the age of 15 can independently consent to participation in the registry. The registry protocol has been approved by the Data Inspectorate of Norway. This study was submitted to the regional ethical committee for medical research which categorized it as a clinical audit study, not in need of their formal approval [21].

At admission for surgery, the patients completed a baseline questionnaire on demographics, lifestyle issues, and PROMs. During the hospital stay, the surgeon recorded data concerning diagnosis, treatment, and comorbidity on a standard registration form. Twelve months after surgery, a questionnaire was distributed by regular post, completed at home by the patients, and returned to the central registry unit without involvement of the treating hospitals. One reminder with a new copy of the questionnaire was sent to those who did not respond.

Patient-reported outcome measures

The PROM questionnaires were identical at baseline and follow-up. The ODI version 2.0 was used to assess pain-related disability. It contains ten questions on limitations of activities of daily living. Each item is rated 0–5 and then transferred into a percentage score ranging from 0 (none) to 100 (maximum pain-related disability) [1].

Pain was reported on the numerical rating scale of 0–10 for both back pain (NRS back pain) and leg pain (NRS leg pain), where 0 = no pain and 10 = worst conceivable pain [2].

Generic health-related quality of life was assessed by the EQ-5D [22], which has been validated for a similar patient population [23]. It evaluates five dimensions: mobility, self-care, activities of daily living, pain, and anxiety and/or depression. For each dimension, the patient describes three possible levels of problems (none, mild-to-moderate, and severe). This descriptive system, therefore, contains 35 = 243 combinations or index values for health status. The total score ranges from −0.59 to 1, where 1 corresponds to perfect health and 0 to death. Negative values are considered to be worse than death.

The patient-rated benefit of the operation was rated on a Global Perceived Effect scale (GPE) at follow-up [24]. The response alternatives were: 1 = “completely recovered”, 2 = “much better”, 3 = “somewhat better”, 4 = “no change”, 5 = “somewhat worse”, 6 = “much worse”, and 7 = “worse than ever”.

Definition of failure and worsening

Patients reporting to be unchanged or worse (categories 4–7) on the GPE scale at 12-month follow-up were classified as “failure”, and those considering themselves worse or worse than ever (GPE 6–7) were classified as “worsening”.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, IBM Version 23.0).

We excluded all patients who did not respond at 12 months, and compared baseline characteristics of both respondents and non-respondents. This strategy was based on a study on a comparable patient population from NORspine and a recent and similar Danish study [25, 26].

For all PROMs, the mean change, mean % change (except for EQ-5D), and mean final raw score were assessed against the GPE by one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc analysis (Tukey, α = 0.05) and by analyses of co-variance (ANCOVA, generalized linear model) with adjustment for baseline scores. Correlation analyses between PROMs and the GPE were done by Spearman rank correlation for all measures, except for the final raw scores in which Pearson was used.

Cutoffs for all scores were estimated by Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves. When analyzing criteria for “failure”, cases with failure were defined as those who reported to be unchanged or worse (categories 4–7) on the GPE scale at 12 months. All other categories on the GPE scale (1–3) were defined as “no failure”. When comparing patients, reporting being considerably worse (GPE 6–7), with those who reported an unchanged status (GPE 4–5), those reporting improvement (GPE 1–3) were excluded from these analyses. To determine the cutoff with the highest sensitivity and specificity for both failure and worsening, the closest point to the upper left corner of the ROC curve was calculated from the coordinates of the curve. Area under the curve (AUC) calculations were performed to determine how well the instruments differentiated between the outcome groups. An AUC value of >0.70 was considered acceptable [27]. The overall accuracy for each cutoff was calculated with a confusion matrix. In the presentation of the results, we included AUC and cutoff values only for variables with an AUC value above 0.70. Results for PROMS with poorer accuracy can be provided on request.

To investigate whether the optimal cutoffs differed between important subgroups in the registry sample, sensitivity analyses were performed between first time vs reoperation and between macroscopic (“open”) vs microscope or loupe-assisted discectomy. To evaluate the impact of different baseline scores on the cutoffs, cutoff calculations were also carried out on those with low- and high baseline disability.

Differences between elective and emergency cases at 12-month follow-up were calculated for all PROMs by Student’s t test and for the GPE by Mann–Whitney U test.

Floor and ceiling effects were assessed by calculating the frequency of the highest and lowest possible scores at baseline. If 15% of patients had a minimal or maximal score value at baseline, these were considered as floor or ceiling effects [27, 28].

Results

6840 out of 9930 (69%) patients had 12-month follow-up data. Among those lost to follow-up were more smokers, a higher number of sickness benefits recipients, and more patients who had been operated previously (Table 2). Furthermore, they had a lower level of education, and fewer were operated on for paresis. Except for back pain, there was no statistical significant difference in PROMs at baseline. Patients who did not respond to the follow-up scored slightly higher for back pain than those who responded.

During surgery, an operating microscope or loupes were used in 5936 of 6840 (87%) cases. A total of 885 (13%) had a reoperation on the same level, 466 (7%) on a different level, and 66 (1%) on both the same and a different level between L1 and S1. The perioperative complication rate was 169 (3%) with 115 (2%) dural tears, 21 (0.3%) nerve root injuries, 24 (0.4%) hematomas requiring transfusion or reoperation, and 9 (0.1%) cardiorespiratory complications.

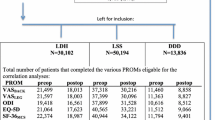

Few data points were missing for the baseline PROMs: ODI (13, 0.2%), EQ-5D (252, 3.7%), NRS back pain (170, 2.5%), and NRS leg pain (159, 2.3%). At 12-month follow-up, 40 (0.6%) were missing data on GPE, 11 (0.2%) on ODI, 520 (7.6%) on EQ-5D, 47 (0.7%) on NRS back pain, and 66 (1%) on NRS leg pain. GPE scores for the entire population are shown in Table 3. Mean improvement (95% CI) for each PROM from baseline to 12-month follow-up for the total sample was 28.7 (28.2–29.2) for the ODI, 0.45 (0.44–0.46) for EQ-5D, 3.2 (3.1–3.3) for back pain, and 4.4 (4.3–4.5) for leg pain, p < 0.001.

The Spearman rank correlation coefficients between the GPE and the change scores of the instruments were high for mean % changes with 0.8 for the ODI, 0.7 for NRS back pain and leg pain, and moderate for mean changes with 0.6 (ODI), 0.5 (NRS back pain), 0.6 (NRS leg pain), and 0.5 (EQ-5D). The Pearson correlation coefficients were high for all the final raw scores with 0.8 (ODI), 0.7 (NRS leg pain), 0.8 (NRS back pain), and 0.7 (EQ-5D). All correlation coefficients were statistically significant (p < 0.001).

ANOVA with post hoc analysis (Tukey, α = 0.05) indicated that the mean changes of all of the PROMs were significantly different between GPE categories 1–3 and 4. The mean of the final raw scores for all of the PROMs, as well as the mean change in ODI, EQ-5D, and NRS leg pain, and the mean ODI% change score at 12 months were able to differentiate between “no change” (4) and “much worse” (6) with statistical significance. Mean changes in NRS back pain, as well as mean % change in NRS back- and leg pain were not statistically significant different between those “unchanged” (4) and those reporting to be “much worse” (6).

After evaluating the mean score differences of all PROMs across the categories of the GPE, the study group concluded that the definition of a score range of 4–7 for “failure” and 6–7 for “worsening” was appropriate (Table 3). Figures illustrating these differences are shown in the appendix (Figs. 1x–4x).

For each GPE outcome group, the baseline adjusted mean scores of the PROMs (ANCOVA) after 12 months are shown in Table 3.

Cutoff values

For differentiation between “failure” vs no failure in the whole cohort, all PROMs had an acceptable AUC of >0.70 (Table 4). The PROM with the highest accuracy was the mean ODI% change score with an AUC of 0.93 and a correct classification rate of 86% (Fig. 1).

For differentiation between “worsening” vs unchanged and slightly worse, the AUCs were poor (<0.70) for score changes of all outcome measures. The final raw scores of all four PROMs showed acceptable AUCs. The PROM with the highest accuracy was the ODI raw score with an AUC of 0.76 and a correct classification rate of 69% (Fig. 2). The ROCs for all of the PROMs are illustrated in the appendix (Figs. 5x–9x).

Based on these cutoff values, the ODI change classified 26%, the ODI% change score 23%, and the ODI raw score at 12 months 27% of lumbar disc surgeries as failure. Failure rates assessed by cutoffs of the less accurate PROMs are shown in the appendix (Table 4x).

The percentages of patients classified as worsening by the cutoffs on the final PROM raw scores were 7% for ODI, 8% for EQ-5D, 7% for NRS leg pain, and 8% for NRS back pain.

Sensitivity analysis

When comparing patients operated for the first time with those who had been operated previously, values for cutoff, sensitivity, and specificity were similar (Tables 2x and 3x in appendix). When investigating the effect of low and high baseline disability (based on the 25th and 75th percentile of the baseline score for ODI), the cutoffs for “failure” and “worsening” in the PROMs varied considerably, both for change scores, % change scores, and the final raw score (Table 1x, appendix). For example, in the group with high disability at baseline, the failure cutoff for the mean % change in ODI was 30% higher than in the low disability group.

Compared to elective surgery, emergency cases had statistically significant worse baseline PROM scores and experienced a greater score improvement at 12 months. Accordingly, no statistically difference in any of the 12-month PROM raw scores was found between these two groups. Furthermore, they reported the same GPE after 12 months, with a median score of 2 (Table 5x, appendix).

Floor and ceiling effects

No floor or ceiling effects were detected. Only 9 (0.1%) patients scored 0 and 7 (0.1%) patients scored 100 on the baseline ODI. Furthermore, 107 (1.6%) scored 0 and 590 (8.8%) scored 10 in the NRS back-pain scale. For the NRS leg pain, scale numbers were 55 (0.8%) for 0 and 728 (10.9%) for 10. In the EQ-5D, only 12 (0.2%) patients scored the minimum and 20 (0.3%) the maximum at baseline.

Discussion

We estimated the optimal cutoff values for failure and worsening 12 months after surgery for lumbar disc herniation, using four recommended PROMs. An ODI% improvement of less than 33% was the most accurate measure for identifying patients for whom the surgery had failed. Back pain, both the mean % change, and the final raw score at 12 months, also showed high accuracy for identifying failure. We found no significant difference in outcome scores among patient groups who considered themselves as “unchanged” or “slightly worse”, which is in accordance with a previous study [12]. A final ODI raw score of more than 48 at 12-month follow-up had the highest accuracy for identifying patients reporting worsening, followed by a final raw score of 7.5 for NRS back pain. A potential explanation for this finding might be that those with a final ODI over a threshold value of 48 will tend to consider themselves as worse, irrespective of the amount of change. These patients are exhausted after more than a year with unresolved severe pain and disability, not compatible with a normal life (Fig. 10x, appendix). One previous study also found a high correspondence between the final raw score and the GPE scale as an external anchor [17].

Compared to the GPE, all cutoffs categorized a higher proportion of the outcomes as “failure” or “worsening”. Since the individual PROMs represent different concepts, the variation between the individual outcome measures and GPE scale is to be expected [10, 11]. For instance, even the disease-specific ten item ODI could fail to address issues important to patients. Individuals might also weigh each item differently according to their preferences.

We chose to classify all patients who scored unchanged or worse (GPE > 3), as “failure” and those scoring much worse or worse than ever (GPE 6–7) as “worsening”. These definitions are supported by our data, i.e., differences in mean PROMs between the GPE groups in ANOVA and ANCOVA analyses, as shown in Table 3 and Figs. 1x–5x (appendix). A large group of patients (n = 1676, 24%) classified themselves as “slightly better”, “unchanged”, or “slightly worse” on the GPE, and would be the most susceptible of being misclassified [12]. While it was not possible to separate the “unchanged” from the “slightly worse” based on PROMs, patients defining themselves as “slightly better” (16%) had a mean improvement in the ODI score of 15.1, more than the previously defined cutoff for the Minimal Clinical Important Change (MCIC) [8]. Hence, it is reasonable not to include them in the failure group. While non-success implies a degree of improvement, failure does not, which might be of importance for litigation issues. The distinction between these two concepts could also be used in the development of predictive models in value-based health care [29].

The mean PROM improvements in this study were in line with results from other clinical trials [30,31,32,33]. Failure and success rates, however, are highly dependent on where the cutoff levels are set to classify outcomes, and types of PROMs used [11]. Mean change in NRS back pain showed the highest failure rate (31%) and mean change in NRS leg pain the lowest (20%). Back-pain intensity is not the primary indication for lumbar discectomy without fusion. It could therefore be expected that, for instance, the NRS leg pain classified a lower failure rate [34]. Our findings indicate that patients reporting failure and worsening tend to be concerned about back pain, even though leg pain may have improved. An explanation may be that a large proportion of patients operated for lumbar disc disease will expect a substantial improvement in back pain [35].

Methodological challenges

The global perceived effect is a frequently used external anchor to define cutoffs on PROMs. Still, it has several weaknesses related to recall bias [17], lack of objectivity [36], and for not taking into account the measurement precision [6]. More objective criteria, such as return to work or use of pain killers, have been proposed [36]. However, they tend to be subgroup specific (e.g., only considering the working population) and may also be susceptible to confounding [37]. Some authors argue that the criteria should be defined prior to treatment by letting the patients quantify, e.g., on a pain scale, how great a satisfying improvement should be [38]. To the best of our knowledge, no such alternative and well-validated external anchors for self-reported questionnaires exist. Unlike the European Spine Tango registry, the NORspine does not collect data on the surgeon’s overall assessment of outcome [39]. Lack of “expert opinion” might represent a weakness. However, surgeons and patients agree only in 50% of cases when assessing outcomes, and surgeons tend to rate the end result over-optimistically [40]. Another weakness related to anchor-based methods is misclassification. In our population, the ODI% cutoff of 33% improvement at 12 months (AUC 0.93, sensitivity/specificity 86%) gave a false-positive rate of 14% and a false-negative rate of 15%.

Importantly, we found that the cutoffs also were highly depending on the baseline PROM score. For instance, severely disabled patients will require disproportionally greater improvements than the less disabled, not to consider the surgery as failed. This is in accordance with findings of other studies and illustrates the importance of taking into account the baseline score while interpreting PROM change scores, regardless of using absolute or percentage change scores [18, 41]. Consequently, one should adjust for the baseline score when using such outcome criteria in clinical trials and risk factor analyses. A possible cause might be higher expectations towards improvements among patients with high baseline pain and disability [42]. Fulfillment of expectations has also been identified as a major predictor for positive patient-rated positive outcome after surgery [35]. Similar to findings by Elkan et al., emergency cases presented with more severe symptoms and had a greater amount of change on the PROM scores, thus reported the same improvement on the GPE scale [43].

Limitations and strengths of this study

Loss to follow-up at 12 months was 31.1%. Two Scandinavian registry studies found that a loss to follow-up of 12–22% did not bias conclusions about treatment effects [25, 26]. Even if baseline PROMs were similar between respondents and non-respondents in our study, several baseline characteristics of non-respondents have been associated with poorer outcomes [44]. This could represent a selection bias, especially when measuring the exact failure and worsening rate, but less so when defining PROM cutoffs over a large range of outcomes. Follow-up was only 12 months, but previous studies have shown mean outcome values to be stable from 1 up to 8 years [26, 45].

An advantage of this study is the large sample size and high external validity due to patient recruitment from everyday practice. In a smaller single-center study from 2013, Gum et al. tried to define clinically important deterioration among patients operated with lumbar fusion for various diagnoses, but found it difficult to define cutoffs. They concluded that a larger patient population was needed to identify accurate cutoffs, since worsening is a relatively rare event [41]. We have used a much larger and more condition-specific cohort.

Future perspectives

Both clinicians and administrators have questioned whether quality registries can improve clinical practice and feedback comprehendible information to patients and clinicians [3]. An advantage of dichotomous outcomes is the possibility to provide risk estimates in terms of probability. In clinical decision-making, percentwise probability would be easier to understand than estimates based on continuous outcome data (e.g., linear regressing coefficients). More research is needed to identify risk factors for adverse outcomes and to learn how such new knowledge can be conveyed efficiently to patients and health care providers.

Conclusion

We have defined cutoff values with acceptable sensitivity and specificity on validated PROMs to classify outcomes as “failure” and “worsening” 12 months after lumbar disc surgery.

Implication

These criteria could facilitate shared decision-making among physicians and patients, quality assessment, and comparison of clinical outcomes across surgical units. In addition to clinically relevant improvements, we propose that rates of failure and worsening should be included in reporting from clinical trials.

References

Baker DJ, PPB, FCT (1990) The Oswestry Disability Index revisited: its reliability, repeatability and validity, and a comparison with the St Thomas’s Disability Index. Back pain. New approaches to rehabilitation and education. 174–186

Mp J, Karoly P (1992) Self-report scales and procedures for assessing pain in adults. In: DC T, Melzack R (eds) Handbook of pain assessment. The Guilford Press, New York, pp 135–151

van Hooff ML, Jacobs WCH, Willems PC et al (2015) Evidence and practice in spine registries: a systematic review, and recommendations for future design of registries. Acta Orthop 86:1–11. doi:10.3109/17453674.2015.1043174

Wyrwich KW, Norquist JM, Lenderking WR, Acaster S (2013) Methods for interpreting change over time in patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res 22:475–483. doi:10.1007/s11136-012-0175-x

Wright A, Hannon J, Hegedus EJ, Kavchak AE (2012) Clinimetrics corner: a closer look at the minimal clinically important difference (MCID). J Man Manip Ther 20:160–166. doi:10.1179/2042618612Y.0000000001

Copay AG, Subach BR, Glassman SD et al (2007) Understanding the minimum clinically important difference: a review of concepts and methods. Spine J 7:541–546

van der Roer N, Ostelo RWJG, Bekkering GE et al (2006) Minimal clinically important change for pain intensity, functional status, and general health status in patients with nonspecific low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 31:578. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000201293.57439.47

Ostelo RWJG, Deyo RA, Stratford P et al (2008) Interpreting Change Scores for Pain and Functional Status in Low Back Pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 33:90–94. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815e3a10

Glassman SD, Copay AG, Berven SH et al (2008) Defining substantial clinical benefit following lumbar spine arthrodesis. J Bone Jt Surg Am 90:1839–1847

Copay AG, Martin MM, Subach BR et al (2010) Assessment of spine surgery outcomes: inconsistency of change amongst outcome measurements. Spine J 10:291–296

Solberg T, Johnsen LG, Nygaard OP, Grotle M (2013) Can we define success criteria for lumbar disc surgery? Estimates for a substantial amount of improvement in core outcome measures. Acta Orthop 84:196–201

Copay AG, Glassman SD, Subach BR et al (2008) Minimum clinically important difference in lumbar spine surgery patients: a choice of methods using the Oswestry Disability Index, Medical Outcomes Study questionnaire Short Form 36, and Pain Scales. Spine J 8:968–974. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2007.11.006

van Kampen DA, Willems WJJ, van Beers LWAH et al (2013) Determination and comparison of the smallest detectable change (SDC) and the minimal important change (MIC) of four-shoulder patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). J Orthop Surg Res 8:40. doi:10.1186/1749-799X-8-40

Fekete TF, Haschtmann D, Kleinstück FS et al (2016) What level of pain are patients happy to live with after surgery for lumbar degenerative disorders? Spine J 16:S12–S18. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2016.01.180

Mroz TE, McGirt M, Chapman JR et al (2014) More “Why” and Less “How”. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 39:S7–S8. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000000539

Deyo RA, Mirza SK (2009) The case for restraint in spinal surgery: does quality management have a role to play? EurSpine J 18(Suppl 3):331–337

Grøvle L, Haugen AJ, Hasvik E et al (2014) Patients’ ratings of global perceived change during 2 years were strongly influenced by the current health status. J Clin Epidemiol 67:508–515. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.001

Mannion AF, Porchet F, Kleinstück FS et al (2009) The quality of spine surgery from the patient’s perspective: part 2. Minimal clinically important difference for improvement and deterioration as measured with the Core Outcome Measures Index. Eur Spine J 18:374–379. doi:10.1007/s00586-009-0931-y

McGirt MJ, Parker SL, Asher AL et al (2014) Role of prospective registries in defining the value and effectiveness of spine care. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 39:S117–S128. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000000552

Larsson S, Lawyer P, Silverstein MB (2010) From concept to reality. Aging (Albany NY). doi:10.1140/epjcd/s2004-03-1694-8

Ruyter KW (2015) REK sør-øst Knut W. Ruyter 22845518 24.06.2015

Dolan P, Gudex C, Kind P, Williams A (1996) The time trade-off method: results from a general population study. Heal Econ 5:141–154

Solberg TK, Olsen JA, Ingebrigtsen T et al (2005) Health-related quality of life assessment by the EuroQol-5D can provide cost-utility data in the field of low-back surgery. Eur Spine J 14:1000–1007

Kamper SJ, Ostelo RW, Knol DL et al (2010) Global Perceived Effect scales provided reliable assessments of health transition in people with musculoskeletal disorders, but ratings are strongly influenced by current status. J Clin Epidemiol 63:760–766

Hojmark K, Stottrup C, Carreon L, Andersen MO (2015) Patient-reported outcome measures unbiased by loss of follow-up. Single-center study based on DaneSpine, the Danish spine surgery registry. Eur spine J Off Publ Eur Spine Soc Eur Spinal Deform Soc Eur Sect Cerv Spine Res Soc. doi:10.1007/s00586-015-4127-3

Solberg TK, Sorlie A, Sjaavik K et al (2011) Would loss to follow-up bias the outcome evaluation of patients operated for degenerative disorders of the lumbar spine?: a study of responding and non-responding cohort participants from a clinical spine surgery registry. Acta Orthop 82:56–63. doi:10.3109/17453674.2010.548024

de Vet HC, Ostelo RW, Terwee CB et al (2007) Minimally important change determined by a visual method integrating an anchor-based and a distribution-based approach. Qual Life Res 16:131–142

Terwee CB, Bot SD, De Boer MR et al (2007) Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol 60:34–42

Resnick DK, Tosteson ANA, Groman RF, Ghogawala Z (2014) Setting the equation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 39:S43–S50. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000000581

Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD et al (2006) Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT): a randomized trial. JAMA 296:2441–2450

Stromqvist B, Fritzell P, Hagg O et al (2013) Swespine: the Swedish spine register: the 2012 report. Eur Spine J 22:953–974

Whitmore RG, Curran JN, Ali ZS et al (2015) Predictive value of 3-month lumbar discectomy outcomes in the NeuroPoint-SD Registry. J Neurosurg Spine 23:1–8. doi:10.3171/2015.1.SPINE14890

Porchet F, Bartanusz V, Kleinstueck FS et al (2009) Microdiscectomy compared with standard discectomy: an old problem revisited with new outcome measures within the framework of a spine surgical registry. Eur Spine J 18(Suppl 3):360–366

Sørile A, Moholdt V, Kvistad KA et al (2012) Modic type i changes and recovery of back pain after lumbar microdiscectomy. Eur Spine J 21:2252–2258. doi:10.1007/s00586-012-2419-4

Mannion AF, Junge A, Elfering A et al (2009) Great expectations: really the novel predictor of outcome after spinal surgery? Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 34:1590–1599

Gatchel RJ, Mayer TG (2010) Testing minimal clinically important difference: additional comments and scientific reality testing. Spine J 10:330–332. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2010.01.019

Glassman SD, Carreon LY (2010) Thresholds for health-related quality of life measures: reality testing. Spine J 10:328–329. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2009.12.026

Ferreira ML, Herbert RD, Ferreira PH et al (2012) A critical review of methods used to determine the smallest worthwhile effect of interventions for low back pain. J Clin Epidemiol 65:253–261

Roder C, Chavanne A, Mannion AF et al (2005) SSE Spine Tango–content, workflow, set-up. www.eurospine.org-Spine Tango. Eur Spine J 14:920–924

Kleinstuck FS, Grob D, Lattig F et al (2009) The influence of preoperative back pain on the outcome of lumbar decompression surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 34:1198–1203

Gum JL, Glassman SD, Carreon LY (2013) Clinically important deterioration in patients undergoing lumbar spine surgery: a choice of evaluation methods using the Oswestry Disability Index, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey, and pain scales. J Neurosurg Spine 19:564–568. doi:10.3171/2013.8.SPINE12804

Mancuso CA, Duculan R, Stal M, Girardi FP (2014) Patients expectations of lumbar spine surgery. Eur Spine J 24:2362–2369. doi:10.1007/s00586-014-3597-z

Elkan P (2016) Similar result after non-elective and elective surgery for lumbar disc herniation : an observational study based on the SweSpine register. Eur Spine J. doi:10.1007/s00586-016-4419-2

Mannion AF, Elfering A (2006) Predictors of surgical outcome and their assessment. Eur Spine J 15(Suppl 1):S93–108

Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, Tosteson ANA et al (2014) Surgical versus nonoperative treatment for lumbar disc herniation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 39:3–16. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000000088

Acknowledgements

This project receives funding from The Norwegian Medical Association—Foundation for quality improvement and patient safety, and The Regional Health Authority of Northern Norway.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Werner, D.A.T., Grotle, M., Gulati, S. et al. Criteria for failure and worsening after surgery for lumbar disc herniation: a multicenter observational study based on data from the Norwegian Registry for Spine Surgery. Eur Spine J 26, 2650–2659 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-017-5185-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-017-5185-5