Abstract

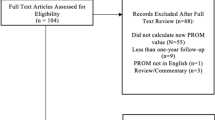

The Core Outcome Measures Index (COMI) is a reliable and valid instrument for assessing multidimensional outcome in spine surgery. The minimal clinically important score-difference (MCID) for improvement (MCIDimp) was determined in one of the original research studies validating the instrument, but has never been confirmed in routine clinical practice. Further, the MCID for deterioration (MCIDdet) has never been investigated; indeed, this needs very large sample sizes to obtain sufficient cases with worsening. This study examined the MCIDs of the COMI in routine clinical practice. All patients undergoing surgery in our Spine Center since February 2004 were asked to complete the COMI before and 12 months after surgery. The COMI has one question each on back (neck) pain intensity, leg/buttock (arm/shoulder) pain intensity, function, symptom-specific well-being, general quality of life, work disability, and social disability, scored as a 0–10 index. At follow-up, patients also rated the global effectiveness of surgery, on a 5-point Likert scale. This was used as the external criterion (“anchor”) in receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analyses to derive cut-off scores for individual improvement and deterioration. Twelve-month follow-up questionnaires were returned by 3,056 (92%) patients. The group mean COMI score change for patients declaring that the “operation helped” was a reduction of 3.1 points; the corresponding value for those whom it “did not help” was a reduction of 0.5 points. The group MCIDimp was hence 2.6 points reduction; the corresponding group MCIDdet was 1.2 points increase (0.5 minus −0.7). The area under the ROC curve was 0.88 for MCIDimp and 0.89 for MCIDdet (both P < 0.0001), indicating that the COMI had good discriminative ability. The cut-offs for individual improvement and deterioration, respectively, were ≥2.2 points decrease (sensitivity 81%, specificity 83%) and ≥0.3 points increase (sensitivity 83%, specificity 88%). The MCIDimp score of 2.2 points was similar to that reported in the original study (2–3 points, depending on external criterion used). The MCIDdet suggested that the COMI is less responsive to deterioration than to improvement, a phenomenon also reported for other spine outcome instruments. This needs further investigation in even larger patient groups. The MCIDs provide essential information for both the planning (sample size) and interpretation of the results (clinical relevance) of future clinical studies using the COMI.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Altman DG, Bland MJ (1994) Statistics notes: diagnostic tests 2: predictive values. BMJ 309:102

Balague F, Mannion AF, Pellise F, Cedraschi C (2007) Clinical update: low back pain. Lancet 369:726–728. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60340-7

Beurskens AJHM, de Vet HCW, Köke AJA (1996) Responsiveness of functional status in low back pain: a comparison of different instruments. Pain 65:71–76. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(95)00149-2

Bombardier C (2000) Outcome assessments in the evaluation of treatment of spinal disorders: summary and general recommendations. Spine 25:3100–3103. doi:10.1097/00007632-200012150-00003

Brozek JL, Guyatt GH, Schunemann HJ (2006) How a well-grounded minimal important difference can enhance transparency of labelling claims and improve interpretation of a patient reported outcome measure. Health Qual Life Outcomes 4:69. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-4-69

Campbell H, Rivero-Arias O, Johnston K, Gray A, Fairbank J, Frost H (2006) Responsiveness of objective, disease-specific, and generic outcome measures in patients with chronic low back pain: an assessment for improving, stable, and deteriorating patients. Spine 31:815–822. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000207257.64215.03

Deyo RA, Battie M, Beurskens AJHM, Bombardier C, Croft P, Koes B, Malmivaara A, Roland M, Von Korff M, Waddell G (1998) Outcome measures for low back pain research: a proposal for standardized use. Spine 23:2003–2013. doi:10.1097/00007632-199809150-00018

Deyo RA, Centor RM (1986) Assessing the responsiveness of functional scales to clinical change: an analogy to diagnostic test performance. J Chronic Dis 39:897–906. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(86)90038-X

Deyo RA, Diehr P, Patrick DL (1991) Reproducibility and responsiveness of health status measures. Statistics and strategies for evaluation. Control Clin Trials 12(Suppl):142S–158S. doi:10.1016/S0197-2456(05)80019-4

Ferrer M, Pellise F, Escudero O, Alvarez L, Pont A, Alonso J, Deyo R (2006) Validation of a minimum outcome core set in the evaluation of patients with back pain. Spine 31:1372–1379. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000218477.53318.bc discussion 1380

Grob D, Bartanusz V, Jeszenszky D, Kleinstück FS, Lattig F, O’Riordan D, Mannion AF (2009) A prospective cohort study of two lumbar fusion techniques. JBJS (Br) (submitted)

Hagg O, Fritzell P, Nordwall A, Group SLSS (2003) The clinical importance of changes in outcome scores after treatment for chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J 12:12–20

Hashimoto H, Komagata M, Nakai O, Morishita M, Tokuhashi Y, Sano S, Nohara Y, Okajima Y (2006) Discriminative validity and responsiveness of the Oswestry Disability Index among Japanese outpatients with lumbar conditions. Eur Spine J 15:1645–1650. doi:10.1007/s00586-005-0022-7

Mannion AF, Elfering A, Staerkle R, Junge A, Grob D, Dvorak J, Jacobshagen N, Semmer NK, Boos N (2007) Predictors of multidimensional outcome after spinal surgery. Eur Spine J 16:777–786. doi:10.1007/s00586-006-0255-0

Mannion AF, Elfering A, Staerkle R, Junge A, Grob D, Semmer NK, Jacobshagen N, Dvorak J, Boos N (2005) Outcome assessment in low back pain: how low can you go? Eur Spine J 14:1014–1026. doi:10.1007/s00586-005-0911-9

Mannion AF, Junge A, Grob D, Dvorak J, Fairbank JC (2006) Development of a German version of the Oswestry Disability Index. Part 2: sensitivity to change after spinal surgery. Eur Spine J 15:66–73. doi:10.1007/s00586-004-0816-z

Mannion AF, Porchet F, Kleinstück F, Lattig F, Jeszenszky D, Bartanusz V, Dvorak J, Grob D (2009) The quality of spine surgery from the patient’s perspective. Part 1. The Core Outcome Measures Index (COMI) in routine practice. Eur Spine J. doi:10.1007/s00586-009-0942-8

Ostelo RW, de Vet HC (2005) Clinically important outcomes in low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 19:593–607. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2005.03.003

Ostelo RW, de Vet HC, Knol DL, van den Brandt PA (2004) 24-item Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire was preferred out of six functional status questionnaires for post-lumbar disc surgery. J Clin Epidemiol 57:268–276. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.09.005

Ostelo RW, Deyo RA, Stratford P, Waddell G, Croft P, Von Korff M, Bouter LM, de Vet HC (2008) Interpreting change scores for pain and functional status in low back pain: towards international consensus regarding minimal important change. Spine 33:90–94

Revicki DA, Cella D, Hays RD, Sloan JA, Lenderking WR, Aaronson NK (2006) Responsiveness and minimal important differences for patient reported outcomes. Health Qual Life Outcomes 4:70. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-4-70

Schunemann HJ, Akl EA, Guyatt GH (2006) Interpreting the results of patient reported outcome measures in clinical trials: the clinician’s perspective. Health Qual Life Outcomes 4:62. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-4-62

Streiner DL, Cairney J (2007) What’s under the ROC? An introduction to receiver operating characteristics curves. Can J Psychiatry 52:121–128

White P, Lewith G, Prescott P (2004) The core outcomes for neck pain: validation of a new outcome measure. Spine 29:1923–1930. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000137066.50291.da

Conflict of interest statement

None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mannion, A.F., Porchet, F., Kleinstück, F.S. et al. The quality of spine surgery from the patient’s perspective: Part 2. Minimal clinically important difference for improvement and deterioration as measured with the Core Outcome Measures Index. Eur Spine J 18 (Suppl 3), 374–379 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-009-0931-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-009-0931-y