Abstract

Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is a peculiar type of pancreatitis of presumed autoimmune etiology. Many new clinical aspects of AIP have been clarified during the past 10 years, and AIP has become a distinct entity recognized worldwide. However, its precise pathogenesis or pathophysiology remains unclear. As AIP dramatically responds to steroid therapy, accurate diagnosis of AIP is necessary to avoid unnecessary surgery. Characteristic dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and fibrosis in the pancreas may prove to be the gold standard for diagnosis of AIP. However, since it is difficult to obtain sufficient pancreatic tissue, AIP should be diagnosed currently based on the characteristic radiological findings (irregular narrowing of the main pancreatic duct and enlargement of the pancreas) in combination with serological findings (elevation of serum γ-globulin, IgG, or IgG4, along with the presence of autoantibodies), clinical findings (elderly male preponderance, fluctuating obstructive jaundice without pain, occasional extrapancreatic lesions, and favorable response to steroid therapy), and histopathological findings (dense infiltration of IgG4-positive plasma cells and T lymphocytes with fibrosis and obliterative phlebitis in various organs). It is apparent that elevation of serum IgG4 levels and infiltration of abundant IgG4-positive plasma cells into various organs are rather specific to AIP patients. We propose a new clinicopathological entity, “IgG4-related sclerosing disease” and suggest that AIP is a pancreatic lesion reflecting this systemic disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 1961, Sarles et al.1 first reported pancreatitis associated with hypergammaglobulinemia and suggested autoimmunity as a pathogenetic mechanism. Since then, the possible role of autoimmunity in causing chronic pancreatitis has drawn the attention of several investigators. In 1992, Toki et al.2 reported four cases of an unusual type of chronic pancreatitis showing diffuse irregular narrowing of the entire main pancreatic duct. In 1995, Yoshida et al.3 summarized the clinical features of these patients and proposed the concept of autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP). Since then, many cases of AIP have been reported in Western countries as well as in Japan. Many new clinical aspects of AIP have been clarified during the past 10 years, and AIP has become a distinct entity recognized worldwide.4–6

After histologically and immunohistochemically examining various organs and extrapancreatic lesions of AIP patients, we proposed the existence of a novel clinicopathological entity, “IgG4-related sclerosing disease”, and suggested that AIP is not simply pancreatitis but a pancreatic lesion reflecting this systemic disease.7,8 Recently, IgG4-related sclerosing diseases of organs other than the pancreas have been reported.9–14 Based on our experience with 32 cases of AIP, this review focuses on the clinical, laboratory, imaging, and histopathological features of IgG4-related sclerosing disease as well as AIP. MEDLINE was searched from 1992 to May 2006 for relevant English-language articles, using a combination of the terms autoimmune pancreatitis, sclerosing pancreatitis, sclerosing cholangitis, sclerosing sialadenitis, retroperitoneal fibrosis, and IgG4. Additional sources were identified by scanning the bibliographies of original and review articles.

Autoimmune pancreatitis

Concept of AIP

AIP is a unique form of pancreatitis in which autoimmune mechanisms are suspected to be involved in the pathogenesis. AIP has many clinical, radiological, serological, and histopathological characteristics as follows: (1) elderly male preponderance; (2) frequent initial symptom of obstructive jaundice without pain; (3) occasional association with impaired pancreatic endocrine or exocrine function and various extrapancreatic lesions; (4) a favorable response to steroid therapy; (5) radiological findings of irregular narrowing of the main pancreatic duct and enlargement of the pancreas; (6) serological findings of elevation of serum γ-globulin, IgG, or IgG4 levels, along with the presence of some autoantibodies; and (7) histopathological findings of dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltration with fibrosis and obliterative phlebitis in the pancreas.15–17 Typical AIP shows diffuse changes of the pancreas, but several cases have shown segmental changes. Localized AIP may extend progressively to the whole pancreas.18,19 The current concept of AIP, including associated extrapancreatic lesions, suggests that AIP may be a systemic disease.7,8,20,21

AIP has been described by various names reflecting different aspects of the entity and each emphasizing the clinical, radiological, or histological findings: for example, chronic inflammatory sclerosis of the pancreas,1 duct-narrowing chronic pancreatitis (DNCP),2 lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis,22 nonalcoholic duct destructive chronic pancreatitis,23 and idiopathic tumefactive chronic pancreatitis.24

Prevalence

AIP is a rare disorder, but its exact incidence is unknown. In a nationwide survey conducted in Japan, 900 patients with AIP were identified,25 and the total number of patients treated for chronic pancreatitis in a year was estimated as 44 700.26 The prevalence rate of AIP among patients with chronic pancreatitis was 1.95% in this survey. We encountered 32 patients (8.4%) with AIP out of 380 patients with chronic pancreatitis clinically diagnosed in our institute. Other reported prevalence rates of AIP among chronic pancreatitis cases are 4.6% (21/451) in Japan,27 5.4% (17/315) in Korea,16 and 6.0% (23/383) in Italy.27 In North America, about 2.5% of pancreatoduodenectomies are performed for AIP because of a mistaken diagnosis of pancreatic cancer,28 and AIP cases represent between 21%29 and 23%28 of pancreatoduodenectomies performed for benign conditions. Reported AIP cases are increasing with the growing awareness of this entity around the world.

Pathogenesis

Serum IgG4 is a subtype of IgG, and its levels are frequently elevated and particularly high in AIP.30,31 Dense infiltration of IgG4-positive plasma cells is seen in various organs of AIP patients.7,8,32–34 These results suggest that IgG4 plays a major role in the pathogenesis of AIP, although the trigger for the IgG4 elevation or its pathogenetic role in AIP has not been clearly disclosed. Antilactoferrin and anti-carbonic anhydrase II (CA-II) antibodies are frequently detected in AIP patients.35 Therefore, lactoferrin and CA-II have been proposed as the target antigens, but this has not yet been fully confirmed. Although the actual effector cells of AIP have not been clearly delineated, the number of activated CD4- and CD8-positive T cells bearing HLADR is increased among the peripheral blood lymphocytes and in the pancreas of AIP patients.35 It has also been reported that this disease is closely associated with the HLA DRB1*0405-DQB1*0401 haplotype, suggesting that the specific peptide presented by these HLA molecules triggers the pathological process of the autoimmunity.36

Although the many above-mentioned findings support an immunologic mechanism of AIP, target antigens for AIP have not been detected. Its preponderant occurrence in elderly men and markedly dramatic response to oral steroid therapy suggest that the pathogenesis of AIP might not be by an autoimmune mechanism but by some other mechanism such as an allergic reaction.

Clinical manifestations

AIP occurs predominantly in elderly men.37 In our series, the mean age of the patients was 68.3 years (range, 29–83 years) and the male-to-female ratio was 4 : 1. In a study in Korea, the mean age was 59.1 years (45–75 years), and the male-to-female ratio was 15:2.16 Patients rarely show typical features of pancreatitis, and the major presenting complaint is painless obstructive jaundice due to associated sclerosing cholangitis (65%16 or 86%38 of cases). The jaundice sometimes fluctuates. Diabetes mellitus, usually type 2, is often (41%39 or 76%16 of cases) observed. In many cases, the diagnoses of diabetes mellitus and AIP are made simultaneously; some patients show exacerbation of preexisting diabetes mellitus with the onset of AIP.40 Tanaka et al.41,42 reported that diabetes mellitus with AIP was caused by T-cell-mediated mechanisms primarily involving islet β-cells as well as pancreatic duct cells. Pancreatic exocrine function is frequently impaired, but marked pancreatic insufficiency is uncommon.43 Some patients have other symptoms related to associated diseases, including salivary gland swelling due to sclerosing sialadenitis, hydronephrosis due to retroperitoneal fibrosis, and lymphadenopathy.44

Laboratory findings

Few patients show marked elevation of serum pancreatic enzymes. The patients with biliary lesions show elevation of serum bilirubin and hepatobiliary enzymes. Some patients show peripheral eosinophilia or elevation of serum IgE levels. Hypergammaglobulinemia (>2.0 g/dl) and elevated serum IgG levels (>1800 mg/dl) are detected in 59%–76%45–47 and 53%16–71%45 of AIP patients, respectively. A diagnostic autoantibody for AIP has not been detected. Autoantibodies including antinuclear antibody and rheumatoid factor are present in 43%–75%39,46,47 and 13%–30%39,46,47 of patients, respectively. Serological findings may change spontaneously during the course of AIP.48 In 2001, Hamano et al.30 reported that serum IgG4 levels are significantly and specifically high in AIP patients and are closely associated with disease activity. According to their report, the use of a cutoff value of 135 mg/dl for the serum IgG4 level resulted in a high rate of accuracy (97%), sensitivity (95%), and specificity (97%) for differentiating AIP from pancreatic cancer. Some AIP patients show elevated serum IgG4 levels in spite of normal IgG levels. However, the sensitivity of elevated serum IgG4 levels is 63%–68% in other reports.15,16,49 Elevation of serum IgG4 levels has been reported in a patient with pancreatic cancer.50

Radiological findings

Typical cases of AIP show diffuse enlargement of the pancreas, the so-called sausage-like appearance, on computed tomography (CT), ultrasonography (US), and magnetic resonance image (MRI). On dynamic CT and MRI, there is delayed enhancement of the swollen pancreatic parenchyma (Fig. 1a).47,51–53 The affected pancreatic lesion shows decreased intensity on the T1-weighted image and increased intensity on the T2-weighted image compared with the signal intensity in the liver.51,53,54 Since inflammatory and fibrous changes involve the peripancreatic adipose tissue, a capsule-like rim surrounding the pancreas, which appears as a low-density area on CT and as a hypointense area on a T2-weighted MRI (Fig. 1b), is detected in some cases.47,51–54 US shows an enlarged hypoechoic pancreas with hyperechoic spots (Fig. 1c).47,51,53 Pancreatic calcification or pseudocyst is uncommon. Some cases show a focal enlargement of the pancreas, similar to that seen with pancreatic cancer.47,55–57 On endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, an irregular, narrow main pancreatic duct is seen diffusely throughout the pancreas in typical cases. The degree of narrowing of the main pancreatic duct varies in the same patient (Fig. 1d). In some cases, there is segmental narrowing of the main pancreatic duct, but upstream dilatation of the distal pancreatic duct is less often noted than in pancreatic cancer (Fig. 1e).47,57 In a majority of AIP patients, both the ventral and dorsal pancreatic ducts are involved, while some patients show the involvement of only the dorsal pancreatic duct. Patients without involvement of the ventral pancreas tend rarely to present with obstructive jaundice.58,59 Stenosis of the extrahepatic or intrahepatic bile duct is frequently observed (Fig. 1e). Marked wall thickening of the extrahepatic bile duct or gallbladder is sometimes detected on US or endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS).53,60,61 Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography does not adequately show the narrow portion of the main pancreatic duct,54 but it can adequately demonstrate stenosis of the bile duct with dilatation of the upper biliary tract.53 Cervical, hilar, and abdominal lymphadenopathy is sometimes detected on CT.47,49 On angiography, encasement of the peripancreatic arteries and stenosis of the portal vein are sometimes observed.47,62 F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography occasionally demonstrates intense FDG uptake in the pancreas of AIP patients.63–65

Radiological findings of patients with autoimmune pancreatitis. a Diffuse enlargement of the pancreas showing delayed enhancement on computed tomography scan. b A hypointense capsule-like rim surrounding the swollen pancreas on a T2-weighted magnetic resonance image. c Diffuse hypoechoic swollen pancreas with hyperechoic spots on US. d Diffuse irregular narrowing of the main pancreatic duct on endoscopic retrograde pancreatography. Degree of narrowing varies. e Stenosis of the lower bile duct and segmental narrowing of the main pancreatic duct of the pancreatic head on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Upstream dilatation of the distal pancreatic duct is less noted than with pancreatic cancer. f After steroid therapy, both stenosis of the bile duct and narrowing of the main pancreatic duct (e) improved

Histopathological and immunohistochemical findings

In gross appearance, the pancreas in AIP shows firm and mass-like enlargement with a thick capsule. The hallmark of the histological findings in the pancreas of AIP patients is dense inflammatory cell infiltration and fibrosis in a periductal and interlobular distribution (Fig. 2a). The inflammatory infiltrate consists mainly of lymphocytes and plasma cells with occasional formation of lymphoid follicles. Perineural infiltration is sometimes detected. Fibrosis is usually diffuse and dense, but loose with stromal edema in some cases. The acinar cells are then more or less replaced by inflammatory cells and fibrosis, and the lobular architecture of the pancreas is almost lost. The pancreatic duct is narrowed by periductal fibrosis and lymphoplasmacytic infiltration (Fig. 2b). The infiltrate is primarily subepithelial, and the ductal epithelium is usually preserved except for sparse infiltration by lymphocytes. This is appropriately labeled as lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis. Another highly characteristic histological finding is obliterative phlebitis of the variably sized pancreatic veins and involvement of the portal vein with lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and proliferation of fibroblasts in and around the wall of the vein (Fig. 2c). Such an inflammatory process widely and intensely involves the contiguous soft tissue and peripancreatic retroperitoneal tissue.22,32,66–69 Saito et al.70 reported that histological recovery of the pancreas, including amelioration of the fibrosis and infiltration of inflammatory cells and a substantial increase in the number of acinar cells, was detected in a patient with AIP after steroid therapy. The wall of the bile duct and gallbladder thickens, histologically showing the same inflammatory process as that of the pancreas. Regional lymph nodes are swollen up to 2.0 cm in diameter, and show histologically marked follicular hyperplasia and dense plasmacytic infiltration in the paracortical and medullary regions.22,32

Histological findings of the pancreas of patients with autoimmune pancreatitis. a Prominent periductal and interlobular fibrosis with a dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and acinar destruction (hematoxylin-eosin stain) b Pancreatic duct narrowed by periductal nonocclusive fibrosis and lymphoplasmacyticinfiltration (elastica-van Gieson stain) c Obliterative phlebitis of the pancreatic veins with prominent lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and fibrosis (elastica-van Gieson stain)

These characteristic histological findings of AIP are detected during its active phase, and may be a gold standard for diagnosing AIP.71 However, diagnosing AIP on the basis of a biopsy or an EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy is sometimes difficult, because of the small sample size.

Immunohistochemically, infiltrating inflammatory cells in the pancreas consist of CD4- or CD8-positive T lymphocytes and IgG4-positive plasma cells (Fig. 3a). Dense infiltration [>30/high-power field (hpf)] of IgG4-positive plasma cells in the pancreas is not observed in chronic alcoholic pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer. Infiltration of abundant IgG4-positive plasma cells is also detected in various organs such as the peripancreatic retroperitoneal tissue, major duodenal papilla, biliary tract, intrahepatic periportal area (Fig. 3b), salivary glands (Fig. 3c), gastric mucosa, colonic mucosa, lymph nodes (Fig. 3d), or bone marrow of AIP patients.7,8,32–34

Diagnostic criteria and differential diagnosis

As it is usually difficult to take specimens from the pancreas, currently, AIP should be diagnosed on the basis of combination with clinical, laboratory, and imaging studies. The Japan Pancreas Society has proposed “Diagnostic Criteria for Autoimmune Pancreatitis, 2002,” containing three items: (1) radiological imaging showing diffuse enlargement of the pancreas and diffuse irregular narrowing of the main pancreatic duct (more than one-third the length of the entire pancreas); (2) laboratory data demonstrating abnormally elevated levels of serum γ-globulin or IgG, or the presence of autoantibodies; and (3) histological examination of the pancreas showing lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and fibrosis. For the diagnosis of AIP, either all of the criteria should be present or criterion 1 together with either criterion 2 or criterion 3. The presence of the imaging criterion is essential for diagnosing AIP.27,72 These criteria are based on the minimum consensus features of AIP to avoid a misdiagnosis pancreatic cancer as far as possible. However, the accumulation of many AIP cases has revealed several diagnostic limitations to these criteria, and revised criteria has been proposed in 2006.73 According to these new criteria, cases showing localized ductal narrowing over less than one-third the length of the pancreas can be diagnosed, and serological findings showing elevation of the serum IgG4 level is included as one diagnostic factor. Recently, new diagnostic criteria have been proposed in Korea74 and the United States75 that include two more factors: response to steroid therapy and other-organ involvement.

The most important disease that should be differentiated from AIP is pancreatic cancer. Clinically, patients with pancreatic cancer and AIP share many features, such as being elderly, having painless jaundice, developing new-onset diabetes mellitus, and having elevated tumor markers.47 Radiologically, focal swelling of the pancreas, the “double-duct sign,” representing strictures in both the biliary and pancreatic ducts, as well as angiographic abnormalities can sometimes be seen in both pancreatic cancer and AIP. As AIP responds dramatically to steroid therapy, accurate diagnosis of AIP can avoid unnecessary laparotomy or pancreatic resection. Imaging findings, such as a mass showing delayed enhancement and a capsule-like rim on dynamic CT or MRI, and segmental narrowing of the main pancreatic duct associated with a less-dilated upstream pancreatic duct, are all useful in differentiating pancreatic cancer from AIP. Measurement of serum IgG4 levels is a useful tool for differentiating between the two diseases. We preliminarily reported that IgG4-immunostaining of biopsy specimens taken from the major duodenal papilla of AIP patients may support the diagnosis of AIP.76 Although improvement in clinical findings with steroid therapy may be useful in the differential diagnosis of AIP from pancreatic cancer, empiric administration of steroids should be avoided in order not to misdiagnose pancreatic cancer as AIP.

It is of uppermost importance to consider the possible presence of AIP in elderly patients presenting with obstructive jaundice and a pancreatic mass.

Treatment and prognosis

Some AIP patients improve spontaneously.77,78 Steroid therapy is clinically, morphologically, and serologically effective in AIP patients (Fig. 1e,1f). In cases with obstructive jaundice, endoscopic or percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage must be done, and in cases of diabetes mellitus, glucose levels must be controlled before steroid therapy is started. The preferred initial dose of prednisolone is 30–40 mg/day, and it is tapered by 5 mg every 1–2 weeks. Serological and imaging tests are performed periodically after commencement of steroid therapy. Usually, pancreatic size is normalized within a few weeks, and biliary drainage becomes unnecessary within 1–2 months. Patients in whom complete radiological improvement is documented can stop their medication, but most other patients require continued maintenance therapy with prednisolone 5 mg/day.78 In half of steroid-treated patients, impaired exocrine or endocrine function improves.40,43 Some AIP patients relapse during maintenance therapy or after stopping steroid medication and should be retreated with high-dose steroid therapy. The indications for steroid therapy in AIP include obstructive jaundice due to stenosis of the bile duct or the presence of other associated systemic diseases, such as retroperitoneal fibrosis.79 Steroid therapy is also effective for sclerosing cholangitis that relapses after surgery.80,81

The long-term prognosis of AIP is not well known. In our 1- to 22-year follow-up study of AIP patients, the prognosis was almost always good, except in two patients who progressed to pancreatic insufficiency after resection.82 It has been reported that recurrent attacks of AIP result in pancreatic stone formation in some cases.38

Clinical subtype

Some young patients suffer from AIP. These young AIP patients are more likely to have abdominal pain and serum amylase elevation than middle-aged or elderly patients.83 According to American66 and Italian67 reports, AIP patients with neutrophilic infiltration in the epithelium of the pancreatic duct are younger, more commonly have inflammatory bowel disease, and have a weaker association with sialadenitis than patients without neutrophilic infiltration. AIP might be a heterogeneous disease with different clinical aspects, and these patients with young onset might be another subtype from the usual AIP as defined in Japan.84 Further international study of a larger series of clinically relevant subtypes of AIP is necessary.

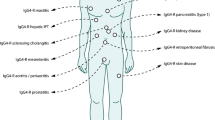

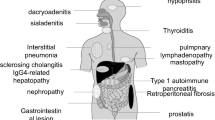

Extrapancreatic lesions of AIP

AIP patients frequently have various extrapancreatic lesions. Since these extrapancreatic lesions show similar histopathological findings to those in the pancreas, they are possibly induced by the same IgG4-related fibroinflammatory mechanisms as AIP.

Multifocal fibrosclerosis is an uncommon fibroproliferative systemic disorder with multiple manifestations, including sclerosing cholangitis, fibrosis of the salivary glands, retroperitoneal fibrosis, Riedel’s thyroiditis, and fibrotic pseudotumor of the orbit. As histopathological findings of these disorders are similar, fibrotic changes with lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and occasional phlebitis, it has been suggested that they are all interrelated and probably represent different manifestations of a common disorder of fibroblastic proliferation.85 Several cases of pancreatic pseudotumor or chronic pancreatitis associated with multifocal fibrosclerosis have been reported.86–89 The development of specific inflammation in extensive organs as well as in the pancreas in AIP patients strongly suggests a close relationship between AIP and multifocal fibrosclerosis.32

Sclerosing cholangitis

Sclerosing cholangitis is a heterogeneous disease that may be associated with choledocholithiasis, biliary tumor, or infection. Sclerosing cholangitis of unknown origin is called primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). PSC is progressive, despite conservative therapy, and involves the intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts, resulting in liver cirrhosis. The effect of steroid therapy is questionable, and liver transplantation currently provides the greatest hope for a possible cure. It occurs in patients in their 30s and 40s and is frequently associated with inflammatory bowel disease.90,91 The pancreatogram is not abnormal in most cases.92

Sclerosing cholangitis is frequently associated with AIP. In many cases, the stenosis is located in the lower part of the common bile duct (Fig. 1e), but EUS or intraductal ultrasonography shows wall thickening of the common bile duct even in the segment in which abnormalities are not clearly observed with cholangiography.60,61 When stenosis is found in the intrahepatic or the hilar hepatic bile duct, the cholangiographic appearance is very similar to that of PSC.92,93 Sclerosing cholangitis associated with AIP responds dramatically well to steroid therapy.79,92,93 The histological findings of sclerosing cholangitis associated with AIP include transmural fibrosis and dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltration of the bile duct wall along with lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and fibrosis in the periportal area of the liver. Compared with PSC, lymphoplasmacytic infiltration is more dense, the degree of fibrosis is less severe, and onion skin appearance is rarely observed. Dense infiltration of IgG4-positive plasma cells has been detected in the bile duct wall and the periportal area of patients with AIP, but it has not been detected in those of patients with PSC.7,8 Furthermore, elevation of serum IgG4 levels was not detected in our three patients with PSC. Given the age at onset, associated diseases, pancreatographic findings, response to steroid therapy, prognosis, and IgG4-related serological and immunohistochemical data, sclerosing cholangitis associated with AIP should be differentiated from PSC.92,93 In particular, discrimination between the two diseases is necessary before making therapeutic decisions.

Recently, three cases (in a 50-year-old woman, a 56-year-old man, and a 77-year-old man) of sclerosing cholangitis with elevated serum IgG4 levels and dense infiltration of IgG4-positive plasma cells in the bile duct wall but with no apparent pancreatic lesions compatible with AIP were reported.9 It is likely that these patients had an IgG4-related systemic disease with no clinical manifestations other than sclerosing cholangitis.

Sclerosing sialadenitis (Kuttner’s tumor and Mikulicz’s disease)

Sclerosing sialadenitis has been referred to as Kuttner’s tumor, on account of its presentation as a firm swelling of the salivary gland that is difficult to differentiate from a neoplasm.94 Mikulicz’s disease is a unique condition that involves enlargement of the lachrymal and salivary glands associated with prominent mononuclear infiltration.95 The pathogenesis of Kuttner’s tumor and Mikulicz’s disease is unknown.

Some cases of AIP associated with Sjögren’s syndrome have been reported.87,96 In our series, swelling of the salivary glands was detected in 7 of 30 (23%) patients with AIP, and it was associated with cervical or mediastinal lymphadenopathy. In these patients, the salivary glands showed dense infiltration of IgG4-positive plasma cells and fibrosis. However, only a few (<3/hpf) IgG4-positive plasma cells were seen to infiltrate the salivary glands of 50 patients with Sjögren’s syndrome, and serum IgG4 levels were not elevated in ten patients with Sjögren’s syndrome.8 Salivary gland function examined by sialochemistry and salivary gland scintigraphy was markedly impaired in many patients with AIP.40,97 Elevation of serum IgG4 levels and dense infiltration of IgG4-positive plasma cells in the salivary glands were usually detected in patients with sclerosing sialadenitis; furthermore, two of five patients with sclerosing sialadenitis developed AIP during follow-up.8,98 These findings suggest a close relationship between AIP and sclerosing sialadenitis. Furthermore, the salivary gland lesion associated with AIP is different from that of Sjögren’s syndrome.

Two reports dealing with IgG4-related sialadenitis have been published.10,11 Kitagawa et al.10 reported that dense infiltration of IgG4-positive plasma cells was detected in the salivary glands of 12 patients with sclerosing sialadenitis (Kuttner’s tumor), and five of these patients (five men; average age, 64.8 years) had associated sclerosing lesions in extrasalivary glandular tissue, such as is the case in AIP, while the remaining seven patients (three men and four women; average age, 64.4 years) had only salivary gland involvement. Yamamoto et al.11 reported that in seven patients (two men and five women; average age, 66.7 years) with Mikulicz’s disease, there was a marked elevation of serum IgG4 levels and dense infiltration of IgG4-positive plasma cells in the lachrymal and salivary glands, and that these findings were not were detected in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. We experienced a patient with AIP showing enlargement of bilateral lacrimal glands that improved after steroid therapy.98 Thus, many cases of sclerosing sialadenitis, including Kuttner’s tumor and Mikulicz’s disease, could be salivary gland lesions of IgG4-related systemic disease.

Retroperitoneal fibrosis

In 1948, Ormond99 described two patients who presented with anuria caused by bilateral ureteral obstruction due to envelopment and compression of the ureters by an inflammatory retroperitoneal process identified as idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis. Idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis is an uncommon entity of obscure origin usually confined to the retroperitoneal space and the pelvic brim.

A total of ten patients (ten men; average age, 63.5 years), including our four patients, have been reported to have retroperitoneal fibrosis associated with AIP.46,100–103 In three cases, retroperitoneal fibrosis occurred 10 to 18 months before the onset of AIP. Dense infiltration of IgG4-positive plasma cells and obliterative phlebitis were found in both the pancreas and retroperitoneal fibrous mass (Fig. 3e). These retroperitoneal fibrotic lesions associated with AIP seem to be retroperitoneal lesions of IgG4-related systemic disease. In all nine of the patients who were treated with steroids, both the retroperitoneal fibrosis and AIP were resolved. Recently, a case of a 52-year-old man with retroperitoneal and mediastinal fibrosis who exhibited elevation of serum IgG4 levels in the absence of AIP was reported.14

Lymphadenopathy

Little attention has been given to lymph node swelling in AIP patients. In a study using gallium-67 scintigraphy, pulmonary hilar gallium-67 uptake was found in 16 of 24 patients with AIP.104 In our series, abdominal lymphadenopathy of up to 2 cm in diameter was observed in five of eight patients at laparotomy, and cervical or mediastinal lymphadenopathy of up to 1.5 cm in diameter was observed in 7 of 28 patients on CT.8 In all these cases, the lymphadenopathy disappeared after steroid therapy. Furthermore, cervical lymphadenopathy was obvious in five of six patients with IgG4-related sclerosing sialadenitis. Dense infiltration of IgG4-positive plasma cells was detected in all abdominal lymph nodes (AIP, n = 6; and sclerosing sialadenitis, n = 1) and cervical lymph nodes (AIP, n = 2; and sclerosing sialadenitis, n = 3) (Fig. 3c). However, only a few IgG4-positive plasma cells were seen to infiltrate abdominal lymph nodes of patients with chronic alcoholic pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer, or cervical lymph nodes of patients with Sjögren’s syndrome.8

Sclerosing cholecystitis

In our series, thickening of the gallbladder was detected on US or CT in 11 of 32 (34%) patients with AIP. Dense infiltration of IgG4-positive plasma cells and lymphocytes, as well as transmural fibrosis, was detected in the gallbladder wall of six of eight examined patients.105

Interstitial pneumonia

A 63-year-old man had concurrent interstitial pneumonia and AIP, both of which improved after steroid therapy. Transbronchial lung biopsy showed dense infiltration of IgG4-positive plasma cells in the alveolar septum.106 Recently, Hirano et al.107 reported that 4 (four men; average age, 69.5 years) of 30 patients with AIP had pulmonary involvement, and they showed good response to steroid therapy.

Tubulointerstitial nephritis

Two cases (in a 64-year-old man108 and a 66-year-old man109) of tubulointerstitial nephritis associated with AIP have been reported. Both diseases improved after steroid therapy. The renal biopsy done in one case showed IgG4-positive staining along the tubular basement membrane and infiltration of IgG4-positive plasma cells into the tubulointerstitium.

Hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor

Hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor is a rare benign lesion characterized by polyclonal lymphoplasmacytic infiltration with fibrosis and is sometimes misdiagnosed as primary hepatic malignant tumor. In two reported cases (a 48-year-old man65 and a 79-year-old man110) of hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor associated with AIP, the tumor showed dense infiltration of IgG4-positive plasma cells, fibrosis, and obliterative phlebitis. Both the hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor and AIP improved after steroid therapy. Zen et al.12 found extensive and dense fibrosis with dense infiltration of IgG4-positive plasma cells and lymphocytes, and obliterative phlebitis was seen in the bile duct lesions of five patients (five men; average age, 65.0 years) with a hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor associated with sclerosing cholangitis. This suggests that these conditions could be included in a common disease entity.

Inflammatory pseudotumor of the lung

We treated a 63-year-old man who had a concurrent inflammatory pseudotumor of the lung and AIP, both of which improved after steroid therapy. The resected lung tumor showed dense infiltration of IgG4-positive plasma cells and lymphocytes intermixed with fibrosis and obliterative phlebitis. Zen et al.13 reported nine cases (five men, four women; average age, 56.8 years) with an inflammatory pseudotumor of the lung that had the same pathological findings as those mentioned above; no cases were associated with AIP, and two cases were associated with sclerosing sialadenitis or lymphadenopathy.

Other reported lesions associated with AIP are pseudotumor of the hypophysis,111 immune thrombocytopenic purpura,112,113 autoimmune sensorineural hearing loss,113 hypothyroidism,114 anosmia,115 and loss of taste.115

IgG4-related sclerosing disease

By histologically and immunohistochemically examining various organs of AIP patients, dense infiltration of IgG4-positive plasma cells as well as CD4- or CD8-positive T lymphocytes and fibrosis have been observed in the peripancreatic retroperitoneal tissue, bile duct wall, gallbladder wall, periportal area of the liver, salivary glands, as well as the pancreas of AIP patients.7,8,32 All extrapancreatic lesions associated with AIP such as sclerosing cholangitis, sclerosing sialadenitis, or retroperitoneal fibrosis show infiltration of abundant IgG4-positive plasma cells, but the infiltration is not detected in those of PSC, Sjögren’s syndrome, sialolithiasis, chronic alcoholic pancreatitis, or pancreatic cancer. Both pancreatic and extrapancreatic lesions of AIP respond well to steroid therapy, being different from PSC.

We therefore propose the existence of a novel clinicopathological entity, an IgG4-related sclerosing disease incorporating sclerosing pancreatitis, cholangitis, sialadenitis, and retroperitoneal fibrosis with lymphadenopathy. It is histopathologically characterized by extensive IgG4-positive plasma cell and T-lymphocyte infiltration of various organs. Major clinical manifestations are apparent in the pancreas, bile duct, salivary glands, and retroperitoneum, in which tissues fibrosis with obliterative phlebitis is pathologically induced. AIP is not simply a pancreatitis, but it is, in fact, a pancreatic lesion reflecting an IgG4-related systemic disease. Sclerosing cholangitis, sclerosing sialadenitis, and retroperitoneal fibrosis associated with AIP are different from PSC, Sjögren’s syndrome, and so-called idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis. Most IgG4-related sclerosing diseases have been found to be associated with AIP, but IgG4-related sclerosing diseases without pancreatic involvement have been reported. Some pseudotumors may be involved in this disease. In some cases, only one or two organs are clinically involved, while in others three or four organs are affected (Fig. 4). The disease occurs predominantly in elderly males, is frequently associated with lymphadenopathy, and responds well to steroid therapy. Serum IgG4 levels and immunostaining with anti-IgG4 antibody are useful in making the diagnosis.8,116 The precise pathogenesis and pathophysiology of IgG4-related sclerosing disease remain unclear (Table 1).

Since malignant tumors are frequently suspected on initial presentation, IgG4-related sclerosing disease should be considered in the differential diagnosis to avoid unnecessary surgery.

Conclusion

AIP has many clinical, serological, morphological, and histopathological characteristic features. AIP should be diagnosed based on combination of these findings. In an elderly man presenting with obstructive jaundice and a pancreatic mass, AIP should be considered as one of the differential diagnoses to avoid unnecessary surgery.

We proposed a new clinicopathological entity of IgG4-related sclerosing disease. It is characterized by extensive IgG4-positive plasma cell and T-lymphocyte infiltration of various organs, and major clinical manifestations are apparent in the pancreas, bile duct, retroperitoneum, and salivary glands, in which tissues fibrosis with obliterative phlebitis is pathologically induced. Much work needs to be done internationally to understand the full spectrum of this disease.

References

H Sarles JC Sarles R Muratoren C Guien (1961) ArticleTitleChronic inflammatory sclerosing of the pancreas—an autonomous pancreatic disease? Am J Dig Dis 6 688–698 10.1007/BF02232341 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaF3c%2Fms1amsQ%3D%3D Occurrence Handle13746542

F Toki T Kozu I Oi (1992) ArticleTitleAn usual type of chronic pancreatitis showing diffuse irregular narrowing of the entire main pancreatic duct on ERCP. A report of four cases Endoscopy 24 640

K Yoshida F Toki T Takeuchi S Watanabe K Shiratori N Hayashi (1995) ArticleTitleChronic pancreatitis caused by an autoimmune abnormality. Proposal of the concept of autoimmune pancreatitis Dig Dis Sci 40 1561–1568 10.1007/BF02285209 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK2MzlsVCqtg%3D%3D Occurrence Handle7628283

K Okazaki (2003) ArticleTitleAutoimmune pancreatitis is increasing in Japan Gastroenterology 125 1557–1558 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.09.011 Occurrence Handle14628815

KO Kim MH Kim SS Lee DW Seo SK Lee (2004) ArticleTitleAutoimmune pancreatitis: it may be a worldwide entity Gastroenterology 126 1214 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.02.044 Occurrence Handle15057766

R Sutton (2005) ArticleTitleAutoimmune pancreatitis—also a Western disease Gut 54 581–583 10.1136/gut.2004.058438 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD2M7pslynsA%3D%3D Occurrence Handle15831898

T Kamisawa N Funata Y Hayashi Y Eishi M Koike K Tsuruta et al. (2003) ArticleTitleA new clinicopathological entity of IgG4-related autoimmune disease J Gastroenterol 38 982–984 10.1007/s00535-003-1175-y Occurrence Handle1:CAS:528:DC%2BD3sXovVKnu7Y%3D Occurrence Handle14614606

T Kamisawa H Nakajima N Egawa N Funata K Tsuruta A Okamoto (2006) ArticleTitleIgG4-related sclerosing disease incorporating sclerosing pancreatitis, cholangitis, sialadenitis and retroperitoneal fibrosis with lymphadenopathy Pancreatology 6 132–137 10.1159/000090033 Occurrence Handle1:CAS:528:DC%2BD28XjslKktL0%3D Occurrence Handle16327291

H Hamano S Kawa T Uehara Y Ochi M Takayama K Komatsu et al. (2005) ArticleTitleImmunoglobulin G4-related lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing cholangitis that mimics infiltrating hilar cholangiocarcinoma: part of a spectrum of autoimmune pancreatitis? Gastrointest Endosc 62 152–157 10.1016/S0016-5107(05)00561-4 Occurrence Handle15990840

S Kitagawa Y Zen K Harada M Sasaki Y Sato H Minato et al. (2005) ArticleTitleAbundant IgG4-positive plasma cell infiltration characterizes chronic sclerosing sialadenitis (Kuttner’s tumor) Am J Surg Pathol 29 783–791 10.1097/01.pas.0000164031.59940.fc Occurrence Handle15897744

M Yamamoto S Harada M Ohara C Suzuki Y Naishiro H Yamamoto et al. (2005) ArticleTitleClinical and pathological differences between Mikulicz’s disease and Sjogren’s syndrome Rheumatology 44 227–234 10.1093/rheumatology/keh447 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD2M%2FlsVSlsw%3D%3D Occurrence Handle15509627

Y Zen K Harada M Sasaki Y Sato K Tsuneyama J Haratake et al. (2004) ArticleTitleIgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis with and without hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor, and sclerosing pancreatitis-associated sclerosing cholangitis. Do they belong to a spectrum of sclerosing pancreatitis? Am J Surg Pathol 28 1193–1203 Occurrence Handle15316319

Y Zen S Kitagawa H Minato H Kurumaya K Katayanagi S Masuda et al. (2005) ArticleTitleIgG4-positive plasma cells in inflammatory pseudotumor (plasma cell granuloma) of the lung Hum Pathol 36 710–717 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.05.011 Occurrence Handle1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2MXntVOisrg%3D Occurrence Handle16084938

Y Zen A Sawazaki S Miyayama K Notsumata N Tanaka Y Nakanuma (2006) ArticleTitleA case of retroperitoneal and mediastinal fibrosis exhibiting elevated levels of IgG4 in the absence of sclerosing pancreatitis (autoimmune pancreatitis) Hum Pathol 37 239–243 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.11.001 Occurrence Handle16426926

K Okazaki K Uchida T Chiba (2001) ArticleTitleRecent concept of autoimmune-related pancreatitis J Gastroenterol 36 293–302 10.1007/s005350170094 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3MzhsFOntA%3D%3D Occurrence Handle11388391

KP Kim MH Kim MH Song SS Lee DW Seo SK Lee (2004) ArticleTitleAutoimmune chronic pancreatitis Am J Gastroenterol 99 1605–1616 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30336.x Occurrence Handle15307882

LP Lara ST Chari (2005) ArticleTitleAutoimmune pancreatitis Curr Gastroenterol Rep 7 101–106 Occurrence Handle15802097

A Horiuchi S Kawa T Akamatsu Y Aoki K Mukawa N Furuya et al. (1998) ArticleTitleCharacteristic pancreatic duct appearance in autoimmune chronic pancreatitis: a case report and review of the Japanese literature Am J Gastroenterol 93 260–263 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00260.x Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1c7islOksQ%3D%3D Occurrence Handle9468255

Y Koga K Yamaguchi A Sugitani K Chijiiwa M Tanaka (2002) ArticleTitleAutoimmune pancreatitis starting as a localized form J Gastroenterol 37 133–137 10.1007/s005350200009 Occurrence Handle11871765

T Kamisawa N Egawa H Nakajima (2003) ArticleTitleAutoimmune pancreatitis is a systemic autoimmune disease Am J Gastroenterol 98 2811–2812 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08758.x Occurrence Handle14687846

MN Toosi J Heathcote (2004) ArticleTitlePancreatic pseudotumor with sclerosing pancreato-cholangitis: is this a systemic disease? Am J Gastroenterol 99 377–382 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04075.x

K Kawaguchi M Koike K Tsuruta A Okamoto I Tabata N Fujita (1991) ArticleTitleLymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis with cholangitis: a variant of primary sclerosing cholangitis extensively involving pancreas Hum Pathol 22 387–395 10.1016/0046-8177(91)90087-6 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK3M3mslGgsg%3D%3D Occurrence Handle2050373

N Ectors B Maillet R Aerts K Geboes A Donner F Borchard et al. (1997) ArticleTitleNon-alcoholic duct destructive chronic pancreatitis Gut 41 263–268 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK2svkslSmug%3D%3D Occurrence Handle9301509 Occurrence Handle10.1136/gut.41.2.263

D Yadav K Notohara TC Smyrk JE Clain RK Pearson MB Famell et al. (2003) ArticleTitleIdiopathic tumefactive chronic pancreatitis: clinical profile, histology, and natural history after resection Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 1 129–135 10.1053/cgh.2003.50016 Occurrence Handle15017505

I Nishimori A Tamaoki S Kawa S Tanaka K Takeuchi T Kamisawa et al. (2006) ArticleTitleInfluence of steroid therapy on the course of diabetes mellitus in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis: findings from a nationwide survey in Japan Pancreas 32 244–248 10.1097/01.mpa.0000202950.02988.07 Occurrence Handle1:CAS:528:DC%2BD28Xktlyqtrs%3D Occurrence Handle16628078

Research Committee of Intractable Diseases of the Pancreas. Result of nationwide survey on chronic pancreatitis in 2002 (in Japanese). In: Otsuki M editor. Annual Report of the Research Committee of Intractable Diseases of the Pancreas. Kitakyushu; 2004. p. 109-2

RK Pearson DS Longnecker ST Chari TC Smyrk K Okazaki L Frulloni et al. (2003) ArticleTitleControversies in clinical pancreatology. Autoimmune pancreatitis: does it exist? Pancreas 27 1–13 10.1097/00006676-200307000-00001 Occurrence Handle12826899

JM Hardacre CA Iacobuzio-Donahue TA Sohn SC Abraham CJ Yeo KD Lillemoe et al. (2003) ArticleTitleResults of pancreaticoduodenectomy for lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis Ann Surg 237 853–859 10.1097/00000658-200306000-00014 Occurrence Handle12796582

SC Abraham RE Wilentz CJ Yeo TA Sohn JL Cameron JK Boitnott et al. (2003) ArticleTitlePancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple resections) in patients without malignancy: are they all “chronic pancreatitis” Am J Surg Pathol 27 110–120 10.1097/00000478-200301000-00012 Occurrence Handle12502933

H Hamano S Kawa A Horiuchi H Unno N Furuya T Akamatsu et al. (2001) ArticleTitleHigh serum IgG4 concentrations in patients with sclerosing pancreatitis N Engl J Med 344 732–738 10.1056/NEJM200103083441005 Occurrence Handle1:CAS:528:DC%2BD3MXitFamt7k%3D Occurrence Handle11236777

K Hirano Y Komatsu N Yamamoto Y Nakai N Sasahira N Toda et al. (2004) ArticleTitlePancreatic mass lesions associated with raised concentration of IgG4 Am J Gastroenterol 99 2038–2040 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40215.x Occurrence Handle15447769

T Kamisawa N Funata Y Hayashi K Tsuruta A Okamoto K Amemiya et al. (2003) ArticleTitleClose relationship between autoimmune pancreatitis and multifocal fibrosclerosis Gut 52 683–687 10.1136/gut.52.5.683 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3s7ntlGqug%3D%3D Occurrence Handle12692053

T Kamisawa N Egawa H Nakajima K Tsuruta A Okamoto Y Hayashi et al. (2005) ArticleTitleGastrointestinal findings in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis Endoscopy 37 1127–1130 10.1055/s-2005-870369 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD2MngtV2ltA%3D%3D Occurrence Handle16281144

T Kamisawa H Nakajima N Egawa Y Hayashi N Funata (2004) ArticleTitleAutoimmune pancreatitis can be confirmed with gastroscopy Dig Dis Sci 49 155–156 10.1023/B:DDAS.0000011618.74277.6d Occurrence Handle14992451

K Okazaki K Uchida M Ohana H Nakase S Uose M Inai et al. (2000) ArticleTitleAutoimmune-related pancreatitis is associated with autoantibodies and Th1/Th2-type cellular immune response Gastroenterology 118 573–581 10.1016/S0016-5085(00)70264-2 Occurrence Handle1:CAS:528:DC%2BD3cXit1Smsb0%3D Occurrence Handle10702209

S Kawa M Ota K Yoshizawa A Horiuchi H Hamano Y Ochi et al. (2002) ArticleTitleHLA DRB10405-DQB10401 haplotype is associated with autoimmune pancreatitis in the Japanese population Gastroenterology 122 1264–1269 10.1053/gast.2002.33022 Occurrence Handle11984513

T Kamisawa M Yoshiike N Egawa H Nakajima K Tsuruta A Okamoto et al. (2004) ArticleTitleChronic pancreatitis in the elderly in Japan Pancreatology 4 223–227 10.1159/000078433 Occurrence Handle15148441

M Takayama H Hamano Y Ochi H Saegusa K Komatsu T Muraki et al. (2004) ArticleTitleRecurrent attacks of autoimmune pancreatitis result in pancreatic stone formation Am J Gastroenterol 99 932–937 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04162.x Occurrence Handle15128363

A Horiuchi S Kawa H Hamano M Hayama K Kiyosawa (2002) ArticleTitleERCP features in 27 patients with autoimmune pancreatitis Gastrointest Endosc 55 494–499 Occurrence Handle11923760

T Kamisawa N Egawa S Inokuma K Tsuruta A Okamoto N Kamata et al. (2003) ArticleTitlePancreatic endocrine and exocrine function and salivary gland function in autoimmune pancreatitis before and after steroid therapy Pancreas 27 235–238 10.1097/00006676-200310000-00007 Occurrence Handle1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2cXks1yisQ%3D%3D Occurrence Handle14508128

S Tanaka T Kobayashi K Nakanishi M Okubo T Murase M Hashimoto et al. (2000) ArticleTitleCorticosteroid-responsive diabetes mellitus associated with autoimmune pancreatitis Lancet 356 910–911 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02684-2 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3cvos1Cmsw%3D%3D Occurrence Handle11036899

S Tanaka T Kobayashi K Nakanishi M Okubo T Murase M Hashimoto et al. (2001) ArticleTitleEvidence of primary β-cell destruction by T-cells and β-cell differentiation from pancreatic ductal cells in diabetes associated with active autoimmune chronic pancreatitis Diabetes Care 24 1661–1667 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3Mvoslagtw%3D%3D Occurrence Handle11522716

T Kamisawa T Nakamura N Egawa H Nakajima K Tsuruta A Okamoto (2006) ArticleTitleDigestion and absorption of patients with autoimmune pancreatitis Hepatogastroenterology 53 138–140 Occurrence Handle16506393

T Kamisawa N Egawa H Nakajima K Tsuruta A Okamoto (2005) ArticleTitleExtrapancreatic lesions in autoimmune pancreatitis J Clin Gastroenterol 39 904–907 10.1097/01.mcg.0000180629.77066.6c Occurrence Handle16208116

S Kawa H Hamano (2003) ArticleTitleAutoimmune pancreatitis and bile duct lesions J Gastroenterol 38 1201–1203 10.1007/s00535-003-1213-9 Occurrence Handle14714265

K Uchida K Okazaki M Asada S Yazumi M Ohana T Chiba (2003) ArticleTitleCase of chronic pancreatitis involving an autoimmune mechanism that extended to retroperitoneal fibrosis Pancreas 26 92–94 10.1097/00006676-200301000-00016 Occurrence Handle12499924

T Kamisawa N Egawa H Nakajima K Tsuruta A Okamoto N Kamata (2003) ArticleTitleClinical difficulties in the differentiation of autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma Am J Gastroenterol 98 2694–2699 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08775.x Occurrence Handle14687819

N Egawa T Irie Y Tu T Kamisawa (2003) ArticleTitleA case of autoimmune pancreatitis with initially negative autoantibodies turning positive during the clinical course Dig Dis Sci 48 1705–1708 10.1023/A:1025426508414 Occurrence Handle14560987

T Kamisawa A Okamoto N Funata (2005) ArticleTitleClinicopathological features of autoimmune pancreatitis in relation to elevation of serum IgG4 Pancreas 31 28–31 10.1097/01.mpa.0000167000.11889.3a Occurrence Handle1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2MXmvVamtLs%3D Occurrence Handle15968244

Kamisawa T, Chen PY, Tu Y, Nakajima H, Egawa N, Tsuruta K, et al. Pancreatic cancer with a serum IgG4 concentration. World J Gastroenterol 2006 (in press)

H Irie H Honda S Baba T Kuroiwa K Yoshimitsu T Tajima et al. (1998) ArticleTitleAutoimmune pancreatitis: CT and MR characteristics AJR Am J Roentgenol 170 1323–1327 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1c3jtlOqtQ%3D%3D Occurrence Handle9574610

N Furukawa T Muranaka K Yasumori R Matsubayashi K Hayashida Y Arita (1998) ArticleTitleAutoimmune pancreatitis: radiologic findings in three histologically proven cases J Comput Assist Tomogr 22 880–883 10.1097/00004728-199811000-00007 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1M%2Flslemuw%3D%3D Occurrence Handle9843225

DV Sahani SP Kalva J Farrell MM Maker S Saini PR Mueller et al. (2004) ArticleTitleAutoimmune pancreatitis: imaging features Radiology 233 345–352 Occurrence Handle15459324

T Kamisawa PY Chen Y Tu H Nakajima N Egawa K Tsuruta et al. (2006) ArticleTitleMRI and MRCP findings in autoimmune pancreatitis World J Gastroenterol 12 2919–2922 Occurrence Handle16718819

A Servais SR Pestieau O Detry P Honore J Belaiche J Boniver et al. (2001) ArticleTitleAutoimmune pancreatitis mimicking cancer of the head of pancreas: report of two cases Acta Gastroenterol Belg 64 227–230 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3Mvis1GisQ%3D%3D Occurrence Handle11475142

M Tabata J Kitayama H Kanemoto T Fukasawa H Goto K Taniwaka (2003) ArticleTitleAutoimmune pancreatitis presenting as a mass in the head of the pancreas: a diagnosis to differentiate from cancer Am Surg 69 363–366 Occurrence Handle12769204

T Kamisawa A Okamoto N Funata (2004) ArticleTitleAutoimmune pancreatitis Gastrointest Endosc 59 865–866 10.1016/S0016-5107(04)00344-X Occurrence Handle15173800

T Kamisawa N Egawa M Shimizu T Igari (2005) ArticleTitleAutoimmune dorsal pancreatitis Pancreas 30 94–95 10.1097/01.mpa.0000153336.50482.59 Occurrence Handle15632708

T Kamisawa Y Tu N Egawa H Nakajima K Tsuruta A Okamoto (2006) ArticleTitleInvolvement of pancreatic and bile ducts in autoimmune pancreatitis World J Gastroenterol 12 612–614 Occurrence Handle16489677

N Hyodo T Hyodo (2003) ArticleTitleUltrasonographic evaluation in patients with autoimmune-related pancreatitis J Gastroenterol 38 1155–1161 10.1007/s00535-003-1223-7 Occurrence Handle14714253

K Hirano Y Shiratori Y Komatsu N Yamamoto N Sasahira N Toda et al. (2003) ArticleTitleInvolvement of the biliary system in autoimmune pancreatitis: a follow-up study Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 1 453–464 10.1016/S1542-3565(03)00221-0 Occurrence Handle15017645

T Kamisawa (2005) ArticleTitleAngiographic findings in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis Radiology 236 371 Occurrence Handle15987989

Y Nakamoto T Saga T Ishimori T Higashi M Mamede K Okazaki et al. (2000) ArticleTitleFDG-PET of autoimmune-related pancreatitis: preliminary results Eur J Nucl Med 27 1835–1838 10.1007/s002590000370 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3M7ltlagtw%3D%3D Occurrence Handle11189947

T Higashi T Saga Y Nakamoto T Ishimori K Fujimoto R Doi et al. (2003) ArticleTitleDiagnosis of pancreatic cancer using fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET)—usefulness and limitations in “clinical reality” Ann Nucl Med 17 261–279 10.1007/BF02988521 Occurrence Handle12932109

A Kanno K Satoh K Kimura A Masamune T Asakura M Unno et al. (2005) ArticleTitleAutoimmune pancreatitis with hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor Pancreas 31 420–423 10.1097/01.mpa.0000179732.46210.da Occurrence Handle16258381

K Notohara LJ Burgart D Yadav S Chari TC Smyrk (2003) ArticleTitleIdiopathic chronic pancreatitis with periductal lymphoplasmacytic infiltration. Clinicopathologic features of 35 cases Am J Surg Pathol 27 1119–1127 10.1097/00000478-200308000-00009 Occurrence Handle12883244

G Zamboni J Luttges P Capelli L Frulloni G Cavallini P Pederzoli et al. (2004) ArticleTitleHistopathological features of diagnostic and clinical relevance in autoimmune pancreatitis: a study on 53 resection specimens and 9 biopsy specimens Virchows Arch 445 552–563 10.1007/s00428-004-1140-z Occurrence Handle15517359

K Suda M Takase Y Fukumura K Ogura A Ueda T Matsuda et al. (2005) ArticleTitleHistopathologic characteristics of autoimmune pancreatitis based on comparison with chronic pancreatitis Pancreas 30 355–358 10.1097/01.mpa.0000160283.41580.88 Occurrence Handle15841047

MH Song MH Kim SJ Jang SK Lee SS Lee J Han et al. (2005) ArticleTitleComparison of histology and extracellular matrix between autoimmune pancreatitis and alcoholic chronic pancreatitis Pancreas 30 272–278 10.1097/01.mpa.0000153211.64268.70 Occurrence Handle15782107

T Saito S Tanaka H Yoshida T Imamura J Ukegawa T Deki et al. (2002) ArticleTitleA case of autoimmune pancreatitis responding to steroid therapy Pancreatology 2 550–556 10.1159/000066092 Occurrence Handle12435868

ST Chari S Echelmeyer (2005) ArticleTitleCan histopathology be the “Gold Standard”“for diagnosing autoimmune pancreatitis? Gastroenterology 129 2118–2120 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.10.034 Occurrence Handle16344083

InstitutionalAuthorName72 Members of the Criteria Committee for Autoimmune Pancreatitis of the Japan Pancreas Society (2002) ArticleTitleDiagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis by the Japan Pancreas Society (in Japanese) Suizou (J Jpn Pancreas Soc) 17 585–587

K Okazaki S Kawa T Kamisawa S Naruse S Tanaka I Nishimori et al. (2006) ArticleTitleClinical diagnostic criteria of autoimmune pancreatitis: revised proposal J Gastroenterol 41 626–631 Occurrence Handle16932998

KP Kim MH Kim JC Kim SS Lee DW Seo SK Lee (2006) ArticleTitleDiagnostic criteria for autoimmune chronic pancreatitis revised World J Gastroenterol 12 2487–2496 Occurrence Handle16688792

MJ Levy MJ Wiersema ST Chari (2006) ArticleTitleChronic pancreatitis: focal pancreatitis or cancer? Is there arole for FNA/biopsy? Autoimmune pancreatitis Endoscopy 38 e30–5 10.1055/s-2006-946648

T Kamisawa Y Yu H Nakajima N Egawa K Tsuruta A Okamoto (2006) ArticleTitleUsefulness of biopsying the major duodenal papilla to diagnose autoimmune pancreatitis: a prospective study using IgG4-immunostaining World J Gastroenterol 12 2031–2033 Occurrence Handle16610052

I Ozden F Dizdaroglu A Poyanli A Emre (2005) ArticleTitleSpontaneous regression of a pancreatic head mass and biliary obstruction due to autoimmune pancreatitis Pancreatology 5 300–303 10.1159/000085287 Occurrence Handle15855829

T Wakabayashi Y Motoo Y Kojima H Makino N Sawabu (1998) ArticleTitleChronic pancreatitis with diffuse irregular narrowing of the main pancreatic duct Dig Dis Sci 43 2415–2425 10.1023/A:1026621913192 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1M%2FjvFOgtg%3D%3D Occurrence Handle9824128

T Kamisawa N Egawa H Nakajima K Tsuruta A Okamoto (2004) ArticleTitleMorphological changes after steroid therapy in autoimmune pancreatitis Scand J Gastroenterol 39 1154–1158 10.1080/00365520410008033 Occurrence Handle1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2cXpsVSlsb0%3D Occurrence Handle15545176

T Taniguchi H Tanio S Seko O Nishida F Inoue M Okamoto et al. (2003) ArticleTitleAutoimmune pancreatitis detected as a mass in the head of the pancreas without hypergammaglobulinemia, which relapsed after surgery. Case report and review of the literature Dig Dis Sci 48 1465–1471 10.1023/A:1024743218697 Occurrence Handle12924637

D Padilla T Cubo P VilLarejo R Pardo A Jara R Plaza Particlede la et al. (2005) ArticleTitleResponse to steroid therapy of sclerosing cholangitis after duodenopancreatectomy due to autoimmune pancreatitis Gut 54 1348–1349 10.1136/gut.2005.070672 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD2Mvjt1GltA%3D%3D Occurrence Handle16099810

T Kamisawa M Yoshiike N Egawa H Nakajima K Tsuruta A Okamoto (2005) ArticleTitleTreating patients with autoimmune pancreatitis: results from a long-term follow-up study Pancreatology 5 234–240 10.1159/000085277 Occurrence Handle15855821

Kamisawa T, Wakabayashi T, Sawabu, N. Autoimmune pancreatitis in young adults. J Clin Gastroenterol 2006 (in press)

T Kamisawa (2005) ArticleTitleClinical subtype of autoimmune pancreatitis Intern Med 44 785–786 10.2169/internalmedicine.44.785 Occurrence Handle16157973

DE Comings KB Skubi JV Eyes AG Motulsky (1967) ArticleTitleFamilial multifocal fibrosclerosis Ann Intern Med 66 884–892 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaF2s7mtFWksQ%3D%3D Occurrence Handle6025229

A Clark RK Zeman PL Choyke FM White MI Burrell EG Grant et al. (1988) ArticleTitlePancreatic pseudotumors associated with multifocal idiopathic fibrosclerosis Gastrointest Radiol 13 30–32 10.1007/BF01889019 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaL1c7mslGnug%3D%3D Occurrence Handle3350266

R Waldram H Kopelman D Tsantoulas R Williams (1975) ArticleTitleChronic pancreatitis, sclerosing cholangitis, and sicca complex in two siblings Lancet 1 550–552 10.1016/S0140-6736(75)91560-3 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaE2M7hsl2lsQ%3D%3D Occurrence Handle47019

I Sjogren B Wengle M Korsgren (1979) ArticleTitlePrimary sclerosing cholangitis associated with fibrosis of the submandibular glands and the pancreas Acta Med Scand 205 139–141 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaE1M7gtVKrtg%3D%3D Occurrence Handle760402 Occurrence Handle10.1111/j.0954-6820.1979.tb06019.x

JM Levey J Mathai (1998) ArticleTitleDiffuse pancreatic fibrosis: an uncommon feature of multifocal idiopathic fibrosclerosis Am J Gastroenterol 93 640–642 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.181_b.x Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1c3jsF2qug%3D%3D Occurrence Handle9576463

NF LaRusso RH Wiesner J Ludwig RL MacCarty (1984) ArticleTitleCurrent concepts. Primary sclerosing cholangitis N Eng J Med 310 899–903 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaL2c7kt1WmsQ%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1056/NEJM198404053101407

RH Wiesner PM Grambsch ER Dickson J Ludwig RC MacCarty EB Hunter et al. (1989) ArticleTitlePrimary sclerosing cholangitis: natural history, prognostic factor and survival analysis Hepatology 10 430–436 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaL1MznvFShuw%3D%3D Occurrence Handle2777204

T Nakazawa H Ohara H Sano T Ando S Aoki S Kobayashi et al. (2005) ArticleTitleClinical differences between primary sclerosing cholangitis and sclerosing cholangitis with autoimmune pancreatitis Pancreas 30 20–25 Occurrence Handle15632695

T Kamisawa N Egawa K Tsuruta A Okamoto N Funata (2005) ArticleTitlePrimary sclerosing cholangitis may be overestimated in Japan J Gastroenterol 40 318–319 10.1007/s00535-004-1543-2 Occurrence Handle15830296

H Kuttner (1886) ArticleTitleUeber entzundliche Tumoren der submaxillar Speicheldruse Bruns Beitr Klin Chir 8 815–828

AJ Schaffer AW Jacobsen (1927) ArticleTitleMikulicz’s syndrome: a report of ten cases Am J Dis Child 34 327–346

PP Muntefusco AC Geiss RL Bronzo S Randall F Kahn MJ McKinley (1984) ArticleTitleSclerosing cholangitis, chronic pancreatitis, and Sjogren’s syndrome: a syndrome complex Am J Surg 147 822–826 10.1016/0002-9610(84)90212-5

T Kamisawa Y Tu N Egawa N Sakaki S Inokuma N Kamata (2003) ArticleTitleSalivary gland involvement in chronic pancreatitis of various etiologies Am J Gastroenterol 98 323–326 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07230.x Occurrence Handle12591049

T Kamisawa H Nakajima T Hishima (2006) ArticleTitleClose relationship between chronic sclerosing sialadenitis and IgG4 Intern Med J 36 527–529 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2006.01119.x Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD28vksVWjug%3D%3D Occurrence Handle16866659

JK Ormond (1948) ArticleTitleBilateral ureteral obstruction due to envelopment and compression by an inflammatory retroperitoneal process J Urol 59 950–954

H Hamano S Kawa Y Ochi H Unno N Shiba M Wajiki et al. (2002) ArticleTitleHydronephrosis associated with retroperitoneal fibrosis and sclerosing pancreatitis Lancet 359 1403–1404 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08359-9 Occurrence Handle11978339

Y Fukukura F Fujiyoshi F Nakamura H Hamada M Nakajo (2003) ArticleTitleAutoimmune pancreatitis associated with idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis AJR 181 993–995 Occurrence Handle14500215

T Kamisawa M Matsukawa M Ohkawa (2005) ArticleTitleAutoimmune pancreatitis associated with retroperitoneal fibrosis JOP 10 260–263

T Kamisawa PY Chen Y Tu H Nakajima N Egawa (2006) ArticleTitleAutoimmune pancreatitis metachronously associated with retroperitoneal fibrosis with IgG4-positive plasma cell infiltration World J Gastroenterol 12 2955–2957 Occurrence Handle16718827

H Saegusa M Momose S Kawa H Hamano Y Ochi M Takayama et al. (2003) ArticleTitleHilar and pancreatic gallium-67 accumulation is characteristic feature of autoimmune pancreatitis Pancreas 27 20–25 10.1097/00006676-200307000-00003 Occurrence Handle12826901

T Kamisawa Y Tu H Nakajima N Egawa K Tsuruta A Okamoto et al. (2006) ArticleTitleSclerosing cholecystitis associated with autoimmune pancreatitis World J Gastroenterol 12 3736–3739 Occurrence Handle16773691

T Taniguchi M Ko S Seko O Nishida F Inoue H Kobayashi et al. (2004) ArticleTitleInterstitial pneumonia associated with autoimmune pancreatitis Gut 53 770 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD2c7osF2hsw%3D%3D Occurrence Handle15082601

K Hirano T Kawabe Y Komatsu S Matsubara O Togawa T Arizumi et al. (2006) ArticleTitleHigh-rate pulmonary involvement in autoimmune pancreatitis Intern Med J 36 58–61 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2006.01009.x Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD28%2FitlSnsA%3D%3D Occurrence Handle16409315

Y Uchiyama-Tanaka Y Mori T Kimura K Sonomura S Umemura N Kishimoto et al. (2004) ArticleTitleAcute tubulointerstitial nephritis associated with autoimmune-related pancreatitis Am J Kid Dis 43 e18–e25 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.12.006 Occurrence Handle14981637

S Takeda J Haratake T Kasai C Takeda E Takazakura (2004) ArticleTitleIgG4-associated idiopathic tubulointerstitial nephritis complicating autoimmune pancreatitis Nephrol Dial Transplant 19 474–476 10.1093/ndt/gfg477 Occurrence Handle14736977

N Sasahira T Kawabe A Nakamura K Shimura H Shimura E Itobayashi et al. (2005) ArticleTitleInflammatory pseudotumor of the liver and peripheral eosinophilia in autoimmune pancreatitis World J Gastroenterol 11 922–925 Occurrence Handle15682495

HJ Vliet Particlevan der RM Perenboom (2004) ArticleTitleMultiple pseudotumors in IgG4-associated multifocal systemic fibrosis Ann Intern Med 141 896–897 Occurrence Handle15583245

A Nakamura H Funatomi A Katagiri K Katayose K Kitamura T Seki et al. (2003) ArticleTitleA case of autoimmune pancreatitis complicated with immune thrombocytopenia during maintenance therapy with prednisolone Dig Dis Sci 48 1968–1971 10.1023/A:1026170304531 Occurrence Handle14627342

H Ohara T Nakazawa H Sano T Ando T Okamoto H Takada et al. (2005) ArticleTitleSystemic extrapancreatic lesions associated with autoimmune pancreatitis Pancreas 31 232–237 10.1097/01.mpa.0000175178.85786.1d Occurrence Handle16163054

K Komatsu H Hamano Y Ochi M Takayama T Muraki K Yoshizawa et al. (2005) ArticleTitleHigh prevalence of hypothyroidism in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis Dig Dis Sci 50 1052–1057 10.1007/s10620-005-2703-9 Occurrence Handle15986853

BS Dooreck P Katz JS Barkin (2004) ArticleTitleAutoimmune pancreatitis in the spectrum of autoimmune exocrinopathy associated with sialoadenitis and anosmia Pancreas 28 105–107 10.1097/00006676-200401000-00018 Occurrence Handle14707740

T Kamisawa (2006) ArticleTitleIgG4-related sclerosing disease Intern Med 45 125–126 10.2169/internalmedicine.45.0137 Occurrence Handle16508224

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by Research for Intractable Disease of the Pancreas, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kamisawa, T., Okamoto, A. Autoimmune pancreatitis: proposal of IgG4-related sclerosing disease. J Gastroenterol 41, 613–625 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-006-1862-6

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-006-1862-6