Abstract

Purpose

To describe emotional barriers and facilitators to deprescribing (the planned reduction or discontinuation of medications) in older adults with cancer and polypharmacy.

Methods

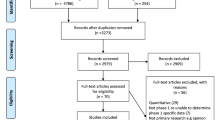

Virtual focus groups were conducted over Zoom with 5 key informant groups: oncologists, oncology nurses, primary care physicians, pharmacists, and patients. All groups were video- and audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Focus group transcripts were analyzed using inductive content analysis, and open coding was performed by two coders. A codebook was generated based on the initial round of open coding and updated throughout the analytic process. Codes and themes were discussed for each transcript until consensus was reached. Emotion coding (identifying text segments expressing emotion, naming the emotion, and assigning a label of positive or negative) was performed by both coders to validate the open coding findings.

Results

All groups agreed that polypharmacy is a significant problem. For clinicians, emotional barriers to deprescribing include fear of moral judgment from patients and colleagues, frustration toward patients, and feelings of incompetence. Oncologists and patients expressed ambivalence about deprescribing due to role expectations that physicians “heal with med[ication]s.” Emotional facilitators of deprescribing included the involvement of pharmacists, who were perceived to be neutral, discerning experts. Pharmacists described emotionally aware communication strategies when discussing deprescribing with other clinicians and expressed increased awareness of patient context.

Conclusion

Deprescribing can elicit strong and predominantly negative emotions among clinicians and patients which could inhibit deprescribing interventions. The involvement of pharmacists in deprescribing interventions could mitigate these emotional barriers.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05046171. Date of registration: September 16, 2021.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Polypharmacy is the concurrent use of multiple medications and is highly prevalent in older adults with cancer. A recent analysis of older adults treated in community oncology settings showed 61.3% were on ≥5 regular medications and 14.5% were on ≥10 regular medications, in addition to their cancer treatment-related and supportive care medications [1]. Polypharmacy is more common in patients with cancer and cancer survivors than in community-dwelling patients without a cancer history [2, 3]. Polypharmacy is associated with adverse outcomes in older adults with cancer [4], including hospitalizations, decreased overall survival, chemotherapy toxicity, falls, and functional decline.

“Deprescribing” is the planned reduction or discontinuation of medications that may pose risk higher than benefit, supervised by a healthcare professional [5]. It has been proposed as a key intervention to reduce potential harms from polypharmacy. However, meta-analyses of deprescribing intervention trials have shown limited effectiveness in reducing adverse outcomes in older adults [6, 7]. Analyses are hampered by wide variability in deprescribing interventions, which range from simple educational interventions targeting prescribers to complex multi-disciplinary team interventions. One recent meta-analysis indicated that comprehensive medication review, typically performed by a pharmacist, may have the most effectiveness (compared to a range of other deprescribing interventions) in reducing adverse outcomes such as potentially inappropriate medication use and mortality [6]. Another meta-analysis suggested a reduction in adverse outcomes for personalized (patient-specific) deprescribing approaches, versus no reduction for general education interventions like educating clinicians on deprescribing [8]. However, there are few studies investigating deprescribing in older adults with cancer [9], and studies that have enrolled these patients have been largely focused on end-of-life deprescribing [10, 11].

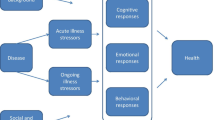

Deprescribing can be considered an example of “de-implementation,” which poses broad challenges for patients, clinicians, and organizations. De-implementation involves the discontinuation of practices that are ineffective, less effective than alternative practices, or potentially harmful [12]. Compared to implementation of a tested intervention, de-implementation induces doubt, confusion, fear, and aversion, and therefore involves unique emotional and cognitive barriers [13, 14]. Although most patients are willing to stop medications if their physician recommends it [15, 16], deprescribing requires more time and effort than that involved in prescribing the medication. Two thirds of outpatient visits in the USA involve prescribing a medication [17], and one study reported the average time spent discussing a new medication was 49 s (5% of total visit time) [18]. In contrast, assessing the risks and benefits of each medication in the context of the patient’s current situation, a precursor to deprescribing, can require 10–15 min or more [9]. In modern allopathic medicine, prescribing a pill to address a concern is an expected interaction in the clinic by both patients [19, 20] and care providers [21, 22], exposing a strong cultural and scientific preference for addressing tractable problems with straightforward solutions (i.e., a pill) [23] over difficult, intractable problems inherent to aging, illness, and disability [24]. Systems barriers such as fragmented care [22] and poor electronic health record interoperability [25] further hinder deprescribing. Although significant attention is paid to addressing care fragmentation and interoperability, structural changes alone may not address a medical culture that has created moral distress in providers and care teams by creating time pressure, emphasizing “productivity,” and prioritizing number of patients seen and procedures completed over quality and comprehensiveness of care [26].

As part of a clinical trial investigating deprescribing interventions for older adults starting chemotherapy (Decreasing Polypharmacy in Older Adults With Curable Cancers Trial, PI: Ramsdale, ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05046171) focus groups were conducted to elicit barriers and facilitators to deprescribing. Although barriers and facilitators to deprescribing have been described previously [27,28,29], we are aware of no prior research on emotional barriers to deprescribing in older adults with cancer. Insufficient attention to emotional and behavioral nuances rooted in a particular culture of medicine or cancer care could limit dissemination and sustainability of deprescribing, even if other barriers are addressed. In this paper, emotional resistance to deprescribing is explored.

Methods

Study design and participants

Virtual focus groups were conducted over Zoom with 5 key informant groups: oncologists (n=6), oncology nurses (n=7), primary care physicians (n=7), pharmacists (n=7), and patients (n=9). All focus groups occurred between November 2020 and August 2021. These participant groups were selected based on involvement in evaluating or experiencing medication usage for older adults seen in the oncology clinic. Oncologists were recruited via email to eligible individuals from University of Rochester Wilmot Cancer Institute, its community affiliate Interlakes Oncology, and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) community affiliate sites. Oncologist participants were eligible if they were in active clinical practice at one or more of the above locations. Oncology nurses, primary care physicians, and pharmacists were recruited via email to eligible individuals from the University of Rochester Medical Center. All individuals in active employment as an oncology nurse, primary care physician, or pharmacist were eligible. Patients were recruited from the Stakeholders for Care in Oncology & Research for our Elders Board (SCOREBoard) [30], which is the patient advisory board for the Cancer and Aging Research Group (CARG). SCOREBoard participants did not have formal training about deprescribing. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the University of Rochester Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided informed consent. Participants were not paid for participation in the focus group activities.

Focus groups were conducted by trained moderators (EC or JB, both research coordinators) with a second moderator (ER, the principal investigator and a practicing geriatric oncologist) observing all groups and taking contemporaneous notes. All groups were video- and audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Focus group discussion lasted an average of 54 min (range 44–62 min). A semi-structured interview guide was tailored to each group using “funnel” (moving from broad topics to narrower ones) and “reverse funnel” (starting with a narrow topic and broadening the focus) approaches to facilitate coverage of all relevant topics related to polypharmacy in older adults and deprescribing (Supplemental Appendix) [31]. Interview guide topics included definitions of polypharmacy, current medication-related workflows, communication about medications, and approaches to deprescribing. An introduction to the focus group introduced the reason for the research, to gather perspectives on polypharmacy and deprescring as part of a NCI-funded trial. The PI (ER) is a colleague of most of the participants. The focus group participants had not previously met or interacted with the other moderators.

Analysis

Debriefing sessions were held with moderators following each group for comparing notes and impressions. Focus group transcripts were analyzed using inductive content analysis [32]. Open coding was performed by the principal investigator (ER) and one additional coder (AM). A codebook was generated based on the initial round of open coding and updated throughout the analytic process. Codes and themes were discussed for each transcript until consensus was reached. A summary of key themes and interpretations for each group was sent to the group participants for comment via email (member checking) [33]. Based on a notable and surprising theme of emotional resistance to deprescribing identified in the open coding, we made a decision to recode the data using emotion coding [34] to explore this unexpected phenomenon in more depth. Emotion coding consisted of identifying text segments expressing emotion, naming the emotion (e.g., frustration, anger, gratitude) and assigning a label of positive or negative. Portions of the transcript not expressing positive or negative emotion were considered neutral. Emotion coding was performed by ER and one additional coder, with discrepancies reviewed and discussed until consensus was reached. All analyses were completed using MAXQDA 2020 software. The COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (COREQ) checklist was used and is included in the supplemental appendix [35].

Results

Analysis revealed agreement by clinicians and patients that polypharmacy was a problem requiring investigation and intervention. There were no statements in any of the focus groups indicating low prioritization or lack of recognition of polypharmacy.

Patient 1: “But many times, people are taking medications that they've just been taking for years and they don't need them anymore, or they've become harmful.” Patient 2: “I agree.” (Patients)

“I think it’s a real problem.…[s]o yeah, polypharmacy is on the problem list. And I think it’s a diagnosis. And really much more dangerous in an elderly population than somebody young.” (Community oncologist)

Despite these statements, discussion about how to address polypharmacy and implement deprescribing elicited multiple barriers and facilitators; this paper focuses on those eliciting emotion as evidenced by use of semantics, tone, or use of sarcasm.

Emotional barriers to deprescribing

Although participants recognized polypharmacy as a problem, prompts to discuss how to explicitly implement deprescribing elicited emotional barriers to deprescribing, including expressions of fear, shame, anxiety, doubt, confusion, and frustration (Table 1 and Supplemental Table 1). Two subthemes related to emotional barriers overlapped within the oncologist, primary care physician (PCP), and pharmacist groups:

-

1.

Clinicians were apprehensive about reactions and moral judgments from colleagues, including being judged as “stupid” or disrespectful of other clinicians’ expertise.

-

2.

Clinicians felt preoccupied about the reactions and moral judgments from patients, such as patients feeling abandoned or angry.

Three further subthemes were identified from the oncologist, PCP, and nurse groups, but not the pharmacist group:

-

1.

Clinicians exhibited frustration with what they perceived to be patients’ unreliability, lack of insight, and perceived resistance about their medications.

-

2.

Clinicians felt uncertain about their competence to deprescribe.

-

3.

System-level issues like care fragmentation and time pressure exacerbated feelings of overwhelm and confusion.

An additional subtheme that emerged within the oncologist group was ambivalence about deprescribing, due to perceived conflict with the physician’s role to treat with medications. Patients expressed a similar variation of this subtheme, believing that the physician’s role compelled them to prescribe the newest and “best” medications.

Emotional facilitators of deprescribing

Subthemes related to emotional facilitators of deprescribing were also identified (Table 2 and Supplemental Table 2). All focus group participants expressed unprompted, spontaneous positive emotion toward pharmacists. Pharmacists were universally viewed as trustworthy, objective, and expert. They were also perceived as being “outside” of the role expectations and time pressures experienced by other clinicians. Pharmacists themselves expressed confidence in their abilities and role related to deprescribing. As a separate subtheme, pharmacists talked about their ability to negotiate the emotions invoked by deprescribing, and specifically noted their training and approach to communicating with physicians; these approaches included specific awareness of the emotional context of these discussions, and the need to mitigate adverse emotional reactions. Lastly, a facilitator subtheme revealed that unlike other clinicians, pharmacists more often situated their comments about patients within a nuanced understanding of the system complexity and patient experience within that system. These comments were typically expressed in an emotionally neutral way, in contrast to the negative emotional content around perceived patient-centered barriers expressed by oncologists, PCPs, and oncology nurses. Unsurprisingly, patients were also attuned to individual context and experience.

Validation of results with emotion coding

Emotion coding revealed 161 text segments expressing negative emotion and 44 statements expressing positive emotion. The most common negative emotions expressed were frustration (n=33), being overwhelmed (n=23), and concern/alarm (n=16). The most common positive emotions expressed were appreciation (n=21), satisfaction (n=7), and pride (n=5). Most negative emotional statements were expressed by oncologists (n=57) and primary care physicians (n=49), followed by nurses (n=29), patients (n=15), and pharmacists (n=11). Primary care physicians had the highest number of positive emotional expressions (n=16) followed by oncologists (n=9), nurses (n=9), patients (n=6), and pharmacists (n=4).

Discussion

In this manuscript, we explore emotional barriers and facilitators of deprescribing to address polypharmacy in older adults with cancer. Polypharmacy is very common in this population, and It is particularly challenging for those starting cancer treatment since chemotherapy regimens typically include the treatment agents themselves along with multiple supportive care medications (e.g., antiemetics). Cancer-related symptoms often require yet more medications. The oncology clinic provides many potential facilitators for addressing polypharmacy: a cancer diagnosis often prompts re-evaluation of goals of care and treatment priorities; oncologists see patients frequently, often assuming primary care roles for their patients, and pharmacists may be more accessible due to their role in evaluating and preparing cancer treatments. Deprescribing within the oncology clinic has been shown in a small pilot study to be feasible and well-accepted by patients [9]. However, data on implementation and outcomes in this context remain very sparse, outside of data surrounding end-of-life deprescribing. A cluster-randomized trial to evaluate and compare two implementation strategies for deprescribing has been developed and is currently accruing patients. Focus groups were conducted with oncologists, nurses, PCPs, pharmacists, and patients prior to trial initiation to provide feedback to refine implementation approaches. Participants unanimously recognized polypharmacy to be a significant issue. Although this may reflect self-selection bias in volunteering for the focus groups, participants expressed an awareness in medical literature and media surrounding polypharmacy in older adults.

Many of the barriers and facilitators emerging from these groups overlap with those previously described in the literature, including individual-level emotional factors such as fear and uncertainty [22, 36, 37]. The frequency of emotional responses in these focus groups, and particularly statements of negative emotion around deprescribing, is noteworthy: although negative emotions were expressed within the context of discussing real or perceived barriers to implementation (such as patient expectations or time pressure), the emotions themselves represent barriers to deprescribing.

Clinicians expressed multiple emotional barriers to deprescribing, including moral emotions about being judged by colleagues or patients, shame, frustration toward patients, and uncertainty. Both clinicians and patients expressed ambivalence about deprescribing, indicating that it conflicted with what they had been taught to expect from a healthcare interaction [38]. Text segments expressing a negative emotion were higher than positive expressions within these focus groups; although all groups stated that polypharmacy is a problem, all groups except pharmacists had difficulty envisioning interventions. Instead, there was a clear tendency to raise perceived barriers to intervention with signifiers of negative emotion including “I feel” statements, sarcasm, and shifts in intonation or volume. By contrast, pharmacists utilized neutral language and expression, endorsed self-confidence and expertise, acknowledged the need for emotionally aware communication around deprescribing, and recognized how patient context could affect their ability to understand medications.

Deimplementation in healthcare, of which deprescribing is an example, can provoke emotions and psychological biases in clinicians that hinder action [39, 40]. The psychological context and requirements of deimplementation differ substantially: deimplementation involves “unlearning,” which can induce emotional reactance that increases,rather than decreases, the commitment to the prior learning [41]. In the case of deprescribing, unease can result from re-evaluating and overturning prior decisions regarding the benefit of medications. Clinicians are susceptible to overvaluing their prior decisions (endowment effect), interpreting new evidence as reaffirming their previously held beliefs (confirmation bias), and prioritizing emotionally vivid feedback such as their experiences with a disgruntled patient in their decisions (availability heuristic) [14]. Deprescribing also challenges the therapeutic illusion favoring action over inaction in medicine [42]: it violates the role expectations of those who “heal with meds” [38] and the belief that “more” and “newer” are necessarily better. Finally, care fragmentation and time pressures resulting from healthcare delivery, organization, and financing, can amplify the effects of these biases. In these focus groups, this amplification could be detected in statements deferring or diffusing responsibility for deprescribing via expression of fears about “staying in one’s lane,” avoiding conflict with other prescribers, facing legal concerns, and anticipating patient reactions.

Patients are susceptible to similar psychological biases and expectations. However, a large survey study of Medicare beneficiaries revealed that two-thirds of older patients wanted to decrease their medication usage, and 92% were willing to stop medications if recommended by their physician [15]. Patients’ desire to de-implement other low-value interventions has also been shown in the context of the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation’s Choosing Wisely campaigns [43], indicating that clinicians may be overestimating patient resistance to deimplementation. However, the time required to engage in education and “unlearning” with patients may be unrealistic in the setting of short clinic visits, particularly oncology visits where other discussions are prioritized.

Nonetheless, all participant groups arrived at a similar resolution for addressing not only systemic but psychological barriers to deprescribing: embracing pharmacists as the locus of deprescribing. Pharmacists were noted as trustworthy by all groups, and they expressed high self-efficacy in understanding and addressing nuanced perspectives around medication use in older adults. Transcript analysis revealed a shared understanding that pharmacists could mediate the cognitive dissonance exposed by the process of deprescribing, displacing this dissonance and its associated emotions onto an objective and expert third party. Helfrich et. al. suggest that a dual process model of cognition is applicable in this situation, whereby “unlearning” (reflective cognition) and substitution of an alternative action (automatic cognition) could work in concert to enhance de-implementation [41]. Pharmacists describe role behaviors supporting clinicians in both processes: they reflect and reframe information to clinicians, and they provide an alternative action for clinicians to perform (e.g., consulting the pharmacist). Furthermore, they help to offset the systemic factors such as time pressure and multitasking that inhibit clinicians’ reflective cognition and capacity for deimplementation [44]. In the focus group, pharmacists described awareness of the emotional impact of their roles, as well as specific training to allow them to navigate and mitigate this impact. Well-designed randomized trials focused on pharmacist-led interventions have successfully reduced high-risk medications in older adults without cancer [45, 46].

This study has several limitations. First, the focus groups were not specifically undertaken to elicit or understand emotions about deprescribing, and it is possible that thematic saturation was not reached. Second, different groups had somewhat different patterns of emotional expression (see Tables 1 and 2), and it is unclear whether these patterns are generalizable across similar groups (i.e., whether nurses consistently express different emotional reactions than oncologists, for example). We did not perform additional focus groups to evaluate these limitations. Third, most participants were recruited from a single institution, and across all groups the participants worked together and knew one another, which may have influenced their emotional expression. Finally, emotions are conveyed via tone of voice, facial expressions, body language, and other cues that cannot be detected in written transcripts. We augmented open coding analysis of the transcripts with contemporaneous notes, recorded videos, and member checking, but some emotional nuance still may have been lost as the focus groups were conducted via teleconferencing.

In conclusion, care providers working in an oncology setting and older adult patients with cancer express emotional reactions that signify potential barriers and faciltators to deprescribing. Emotional barriers include worry, fear, and ambivalence; facilitators include trust in pharmacist expertise, emotionally aware communication, and empathy to patient context. Despite a growing literature and associated guidelines supporting planned medication discontinuation, deprescribing remains an uncommon practice in the oncology clinic for older adults with cancer. Although this lack of uptake is related to multiple systemic and institutional barriers, the specific emotions induced by contemplation of deprescribing may be underappreciated barriers. How these emotions either inhibit or facilitate deprescribing behaviors is rarely explored in the literature. Deimplementation (such as deprescribing) invokes different emotional responses and biases compared to implementation (such as prescribing), which may create unique difficulties in designing interventions to reduce inappropriate medication use. Many of the emotional responses are linked to either common cognitive biases (such as overcommitment to one’s prior decision to initiate a medication) or to deeply acculturated values in medicine (such as healing with medications, or using the “newest and best” technologies). Utilizing solely logic- and data-based retraining is unlikely to address these emotional barriers. Instead, the focus groups as a whole suggest a different approach: the transference of some responsibility for deimplementation onto an “objective” and expert adjudicator: the clinical pharmacist. Due to their role and training, clinical pharmacists may not be subject to the same cognitive biases and role acculturation, and they may be able to assist clinicians in their own “unlearning” processes by providing reframing and substituted action. In our clinical trial, pharmacist-led deprescribing will be tested against a patient education brochure in the oncology clinic for older adults with polypharmacy initiating cancer treatment. The trial is designed with an adaptive “lead-in” period to refine and adapt the pharmacist intervention, to determine how best to utilize the pharmacist skillset to enhance facilitation of deprescribing and mitigate identified barriers. The cluster-randomized portion of the trial will collect both effectiveness and feasibility outcomes. Since clinical pharmacists are tightly integrated into oncology practice, this poses a scalable and effective mechanism for decreasing polypharmacy and improving outcomes in these patients. Further research is needed to address how deprescribing is optimally performed in older patients with cancer and polypharmacy [47].

Data Availability

The raw/processed data required to reproduce the above findings cannot be shared at this time due to anticipated difficulty de-identifying transcripts, and because the data also forms part of an ongoing study.

References

Mohamed MR, Mohile SG, Juba KM et al (2023) Association of polypharmacy and potential drug-drug interactions with adverse treatment outcomes in older adults with advanced cancer. Cancer 129:1096–1104

Hsu CD, Nichols HB, Lund JL (2022) Polypharmacy and medication use by cancer history in a nationally representative group of adults in the USA, 2003-2014. J Cancer Surviv 16:659–666

Hsu HF, Chen KM, Belcastro F et al (2021) Polypharmacy and pattern of medication use in community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review. J Clin Nurs 30:918–928

Mohamed MR, Ramsdale E, Loh KP et al (2020) Associations of Polypharmacy and Inappropriate Medications with Adverse Outcomes in Older Adults with Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oncologist 25:e94–e108

Reeve E, Gnjidic D, Long J et al (2015) A systematic review of the emerging de fi nition of 'deprescribing' with network analysis: implications for future research and clinical practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol 80:1254–1268

Bloomfield HE, Greer N, Linsky AM et al (2020) Deprescribing for Community-Dwelling Older Adults: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 35:3323–3332

Ulley J, Harrop D, Ali A et al (2019) Deprescribing interventions and their impact on medication adherence in community-dwelling older adults with polypharmacy: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr 19:15

Page AT, Clifford RM, Potter K et al (2016) The feasibility and effect of deprescribing in older adults on mortality and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 82:583–623

Whitman A, DeGregory K, Morris A et al (2018) Pharmacist-led medication assessment and deprescribing intervention for older adults with cancer and polypharmacy: a pilot study. Support Care Cancer 26:4105–4113

Kutner JS, Blatchford PJ, Taylor DH Jr et al (2015) Safety and benefit of discontinuing statin therapy in the setting of advanced, life-limiting illness: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 175:691–700

Lindsay J, Dooley M, Martin J et al (2015) The development and evaluation of an oncological palliative care deprescribing guideline: the 'OncPal deprescribing guideline'. Support Care Cancer 23:71–78

Walsh-Bailey C, Tsai E, Tabak RG et al (2021) A scoping review of de-implementation frameworks and models. Implement Sci 16:100

Norton WE, Chambers DA (2020) Unpacking the complexities of de-implementing inappropriate health interventions. Implement Sci 15:2

Ubel PA, Asch DA (2015) Creating value in health by understanding and overcoming resistance to de-innovation. Health Aff (Millwood) 34:239–244

Reeve E, Wolff JL, Skehan M et al (2018) Assessment of Attitudes Toward Deprescribing in Older Medicare Beneficiaries in the United States. JAMA Intern Med 178:1673–1680

Reeve E, Low LF, Hilmer SN (2019) Attitudes of Older Adults and Caregivers in Australia toward Deprescribing. J Am Geriatr Soc 67:1204–1210

Santo LOT, Schappert SM (2022) National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey - Community health centers: 2020 national summary tables. National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD

Tarn DM, Paterniti DA, Kravitz RL et al (2008) How much time does it take to prescribe a new medication? Patient Educ Couns 72:311–319

Sites BD, Harrison J, Herrick MD et al (2018) Prescription Opioid Use and Satisfaction With Care Among Adults With Musculoskeletal Conditions. Ann Fam Med 16:6–13

Martinez KA, Rood M, Jhangiani N et al (2018) Association Between Antibiotic Prescribing for Respiratory Tract Infections and Patient Satisfaction in Direct-to-Consumer Telemedicine. JAMA Intern Med 178:1558–1560

Cockburn J, Pit S (1997) Prescribing behaviour in clinical practice: patients' expectations and doctors' perceptions of patients' expectations--a questionnaire study. BMJ 315:520–523

Doherty AJ, Boland P, Reed J, Clegg AJ, Stephani AM, Williams NH, Shaw B, Hedgecoe L, Hill R, Walker L (2020) Barriers and facilitators to deprescribing in primary care: a systematic review. BJGP Open 4(3). https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgpopen20X101096

Rittel HW, Webber MM (1973) Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci 4:155–169

Frank AW (1995) The Wounded Storyteller: Body, Illness, and Ethics. University of Chicago Press

Allen AS, Sequist TD (2012) Pharmacy dispensing of electronically discontinued medications. Ann Intern Med 157:700–705

Meier DE, Back AL, Morrison RS (2001) The inner life of physicians and care of the seriously ill. JAMA 286:3007–3014

Sawan M, Reeve E, Turner J et al (2020) A systems approach to identifying the challenges of implementing deprescribing in older adults across different health-care settings and countries: a narrative review. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 13:233–245

Lundby C, Graabaek T, Ryg J et al (2019) Health care professionals' attitudes towards deprescribing in older patients with limited life expectancy: A systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 85:868–892

Anderson K, Stowasser D, Freeman C et al (2014) Prescriber barriers and enablers to minimising potentially inappropriate medications in adults: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMJ Open 4:e006544

Gilmore NJ, Canin B, Whitehead M et al (2019) Engaging older patients with cancer and their caregivers as partners in cancer research. Cancer 125:4124–4133

Morgan DL (2019) Basic and Advanced Focus Groups. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J (2018) Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. SAGE Publications

Lincoln Y, Guba E (1985) Naturalistic Inquiry. Sage Publications, Newbury Park, CA

Saldaña J (2021) The coding manual for qualitative researchers, 4th edn. CA, SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19:349–357

Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I et al (2013) Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: a systematic review. Drugs Aging 30:793–807

Paque K, Vander Stichele R, Elseviers M et al (2019) Barriers and enablers to deprescribing in people with a life-limiting disease: A systematic review. Palliat Med 33:37–48

George LS, Epstein RM, Akincigil A et al (2023) Psychological Determinants of Physician Variation in End-of-Life Treatment Intensity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis. J Gen Intern Med 38:1516–1525

Grimshaw JM, Patey AM, Kirkham KR et al (2020) De-implementing wisely: developing the evidence base to reduce low-value care. BMJ Qual Saf 29:409–417

Duberstein PR, Hoerger M, Norton SA et al (2023) The TRIBE model: How socioemotional processes fuel end-of-life treatment in the United States. Soc Sci Med 317:115546

Helfrich CD, Rose AJ, Hartmann CW et al (2018) How the dual process model of human cognition can inform efforts to de-implement ineffective and harmful clinical practices: A preliminary model of unlearning and substitution. J Eval Clin Pract 24:198–205

McDaniel CE, House SA, Ralston SL (2022) Behavioral and Psychological Aspects of the Physician Experience with Deimplementation. Pediatr Qual Saf 7:e524

Silverstein W, Lass E, Born K et al (2016) A survey of primary care patients' readiness to engage in the de-adoption practices recommended by Choosing Wisely Canada. BMC Res Notes 9:301

Einstein GO, McDaniel MA, Williford CL et al (2003) Forgetting of intentions in demanding situations is rapid. J Exp Psychol Appl 9:147–162

Tannenbaum C, Martin P, Tamblyn R et al (2014) Reduction of inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions among older adults through direct patient education: the EMPOWER cluster randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med 174:890–898

Martin P, Tamblyn R, Benedetti A et al (2018) Effect of a Pharmacist-Led Educational Intervention on Inappropriate Medication Prescriptions in Older Adults: The D-PRESCRIBE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 320:1889–1898

Nightingale G, Mohamed MR, Holmes HM et al (2021) Research priorities to address polypharmacy in older adults with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol 12:964–970

Funding

The work was funded through NCI K08CA248721 (E.R.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Erika Ramsdale, Sally Norton, Paul Duberstein; Methodology: Erika Ramsdale, Holly Holmes, Lisa Zubkoff, Supriya Mohile, Sally Norton, Paul Duberstein; Formal analysis and investigation: Erika Ramsdale, Arul Malhotra, Sally Norton, Paul Duberstein; Writing - original draft preparation: Erika Ramsdale; Writing - review and editing: all authors; Funding acquisition: Erika Ramsdale; Supervision: Holly Holmes, Lisa Zubkoff, Sally Norton, Supriya Mohile.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics accordance

This study was reviewed and approved under the Office of Human Subjects Protection (OHSP) and University of Rochester (UR) policies, and in accordance with Federal regulation 45 CFR 46 under the University’s Federal-wide Assurance (FWA00009386).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ramsdale, E., Malhotra, A., Holmes, H.M. et al. Emotional barriers and facilitators of deprescribing for older adults with cancer and polypharmacy: a qualitative study. Support Care Cancer 31, 636 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-08084-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-08084-9