Abstract

Purpose

In daily practice, oncologists and nurses frequently need to decide whether or not to refer a patient for professional mental health care. We explored the indicators oncologists and nurses use to judge the need for professional mental health care in patients with cancer.

Methods

In a qualitative study, oncologists (n = 8) and nurses (n = 6) were each asked to select patients who were or were not referred for professional mental health care (total n = 75). During a semi-structured interview, they reflected on their decision concerning the possible referral of the patient. Thematic analysis was used to analyze the data.

Results

Respondents reported using a strategy when judging whether professional mental health care was needed. They allowed patients time to adjust, while monitoring patients’ psychological well-being, especially if patients exhibited specific risk factors. Risk and protective factors for emotional problems included personal, social, and disease- and treatment-related factors. Respondents considered referral for professional mental health care when they noted specific indicators of emotional problems. These indicators included lingering or increasing emotions, a disproportionate intensity of emotions, and emotions with a negative impact on a patient’s daily life or treatment.

Conclusions

This study identified the strategy, risk and protective factors, and the indicators of emotional problems used by oncologists and nurses when judging the need for professional mental health care in patients with cancer.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Oncologists and nurses can play an important role in the identification of patients in need of professional mental health care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cancer occurrence is a major stressor in patients and results in a wide range of emotions. Most patients are able to manage these emotions with support from relatives, friends, and caregivers [1,2,3,4]. However, some patients have difficulty dealing with the emotions triggered by a traumatic event such as the diagnosis of cancer, illustrated by the increased incidence of mental disorders such as mood or anxiety disorders [5,6,7]. These patients may require professional mental health care to help them cope.

Several screening instruments have been developed to help identify patients likely to require professional mental health care, one example being the Distress Thermometer [8]. However, it has been consistently observed that the majority of patients scoring above the cutoff for distress subsequently decline professional mental health care [9,10,11,12]. Typically, while over 30–40% of patients score above the cutoff for distress [12, 13], only around 10–15% of patients report a need for professional mental health care [7, 12, 14]. It has been argued that this discrepancy is either due to suboptimal implementation of distress screening and referral programs or to mental health care-related stigma [15]. While these factors may play a role, the underlying problem seems more fundamental in nature. Many patients report that they do not need professional mental health care but instead prefer support from family, friends, and/or clinicians to help them deal with the emotions associated with cancer and its treatment [12]. In addition, from a theoretical perspective, a distinction should be made between adaptive and maladaptive emotions [12]. Emotions are essentially adaptive—they help us adjust to events in the environment, such as the diagnosis and treatment of cancer [16]. Equally, emotions can sometimes hamper adaptation, leading to significant distress and disability. Emotions are maladaptive if they are disproportionally severe or persistent, and if they interfere with functioning [17]. Professional mental health care is indicated only in the event of maladaptive emotions [12]. In light of these considerations, we can question the value of distress screening instruments. While these instruments are appropriate for determining distress, they are not designed for determining whether patients’ emotions are maladaptive, and they appear less well-suited to determining the need for professional mental health care. This conclusion highlights a need for additional indicators that can reliably distinguish those patients who genuinely require professional mental health care.

In daily practice, oncologists and nurses play a key role in identifying patients who need professional mental health care and frequently need to decide whether or not to refer a patient. We therefore expected that this clinical experience may have led to valuable, intuitive knowledge concerning indicators of emotional problems that require professional mental health care. To detect distress, oncologists and nurses reportedly look for affective, verbal, and physical indicators of distress, using techniques such as getting to know the patient, intuition and subjective judgment, as well as familiarity with the patient’s medical history [18, 19]. However, the specific indicators that are used to judge the need for professional mental health care are unknown. The qualitative study described here aimed to explore which indicators oncologists and nurses use when judging the need for professional mental health care in patients with cancer.

Methods

Setting, design, and research team

This explorative study was conducted at departments of medical oncology in two academic hospitals and one teaching hospital in the Netherlands between September 2019 and January 2020. Applying a qualitative study design [20], a researcher with experience in qualitative research methods (JK) interviewed oncologists and nurses. She was supervised by a researcher specialized in qualitative research methods (AdK) and other members of the team with backgrounds in psychology, psychiatry, medical oncology, and epidemiology. Throughout the study, the researcher made notes in a logbook, which were critically discussed with the supervisors.

Procedure and data collection

The researcher initially presented the study plan at a staff meeting (of oncologists or nurses) in the departments participating in the study. Oncologists and nurses who expressed interest were provided with further information and received a written invitation to participate. All participants confirmed their consent in writing. The aim was to recruit six medical oncologists and six nurses. Participants were told that they would be interviewed regarding their considerations when deciding if a patient should be referred for professional mental health care. To thoroughly explore these considerations, they were asked to prepare for the interview by selecting three of their cancer patients who were referred for professional mental health care and three who were not referred. Purposive sampling based on age and gender was encouraged to maximize the diversity of patients, as these factors are known to be associated with emotional responses to cancer.

The researcher did not know the clinicians she interviewed. The interview was conducted at the clinician’s office, and during the interview, respondents reflected on their decisions concerning referral or non-referral of their patients for professional mental health care. Interviewees had access to electronic patient files which included notes on patients’ psychosocial well-being and care needs. While reviewing these notes, the researcher prompted respondents to “think aloud” concerning why they felt that the patient needed or did not need professional mental health care [21]. The interviewer used a topic list to guide the interview [18, 19, 22,23,24] (see Supplementary file 1). One interview was interrupted and was repeated at a later moment.

We expected that six medical oncologists and six nurses, each reporting on six patients, would result in useful clinical information, while with the expected total of 72 interviews (= 12 clinicians *6 interviews each), we would not exceed our capacity to analyze interviews.

All interviews were audio-recorded, and field notes were taken after the interview. The duration of the interviews was approximately 1 h on average. Data collection ended when data saturation was achieved (at the patient level). The research team’s conclusion that data saturation had been achieved was based on a systematic discussion of the data, including newly collected data.

Data analysis

Data collection and analysis constituted an iterative process. The interviews were transcribed verbatim by a research assistant, and the interviewer ensured the accuracy of the transcription. The researchers analyzed the transcribed interviews using thematic analysis [25]. The six steps in the analysis comprised (1) becoming familiar with the data; (ii) generating initial codes; (iii) searching for themes; (iv) reviewing themes; (v) defining and naming themes; and (vi) producing the report [25,26,27]. The qualitative data analysis software MAXQDA was used.

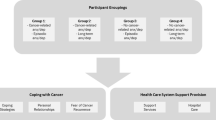

Two researchers (JK, AdK) analyzed the data independently and any discrepancies were discussed until an agreement was reached. The data analysis was repeatedly discussed with the research team, and various conceptualizations of codes and themes were discussed and justified among the research team. During analysis, the need arose for a model to organize the codes, and the model of psychological adjustment to chronic disease was chosen as a sensitizing concept to help organize the codes [28]. This model distinguishes the patient’s personal, social, and environmental background from possible emotional, cognitive, and behavioral responses to disease or stressors (see Fig. 1). Below, the codes that concerned the patient’s personal, social, and environmental background are referred to as “risk and protective factors,” while the codes that concerned emotional, cognitive, and behavioral responses to disease/stressors are referred to as “indicators for a referral” (see Results section). The coding system is described in detail in Supplementary file 2.

Model of psychological adjustment to chronic disease (reproduced from Disability and Rehabilitation [28])

Results

Participants

Eight oncologists and six nurses participated in the study (n = 14). Their mean age was 46.4 (SD 9.1) years; 11 were female, 3 male; 10 worked in an academic setting, including 4 in a teaching hospital; participants had 12.64 (SD 6.36) years of clinical experience in oncology; 7 had taken a course or had training in patients’ psychosocial well-being while 7 had not. None of the departments of medical oncology involved in the study had implemented a procedure for systematic distress screening using the Distress Thermometer/Problem List or another instrument. Oncologists and nurses relied on their clinical judgment to identify patients in need of referral for professional mental health care. Two oncologists and two nurses reported that they had occasionally used the Distress Thermometer/Problem List.

Participants selected a total of 75 patients. The mean age of patients was 58.4 (SD 11.4) years; 37 were female, 38 male; their diagnoses were colorectal (n = 31), skin (n = 5; melanoma), ovarian (n = 2), pancreas (n = 5), bladder (n = 2), head and neck (n = 7), stomach (n = 2), testicle (n = 3), breast (n = 8), and prostate (n = 2) cancer (no information on diagnosis: n = 8). Patients were treated with curative intent (n = 19) or in a palliative setting (n = 40) (no information: n = 16). Clinicians selected more patients who were referred for professional mental health care (n = 50) than patients who were not referred (n = 25), as they considered referred patients to be more informative concerning indicators for referral than non-referred patients.

Strategy, risk and protective factors, and indicators

The analysis revealed three main themes in the oncologists’ and nurses’ reflections: (1) a strategy to judge whether professional mental health care was needed, (2) risk and protective factors for the development of emotional problems, and (3) indicators for referral. Figure 2 provides an overview and Table 1 provides examples of respondents’ comments. Overall, oncologists and nurses mentioned comparable strategies, factors, and indicators, although specific examples varied. One oncologist and two nurses mentioned that nurses usually have more time than oncologists to evaluate a patient’s personal and social background.

Strategy

Respondents gave patients the opportunity to adjust to the diagnosis and treatment of cancer. Rather than immediately offering professional help, patients were first allowed time to deal with their emotions and were monitored regarding psychological well-being. Monitoring consisted of note-taking in the patient record, together with observation and interviews with the patient. Risk and protective factors were taken into account by respondents when judging whether professional mental health care would be needed. Respondents stated that they became more attentive when they noticed risk factors because patients exhibiting risk factors were considered more likely to experience emotional problems, compared to patients without risk factors. Some respondents informed at-risk patients that professional mental health care would be available if needed. Other respondents mentioned providing additional support to at-risk patients, for example through more frequent calls or visits.

A decision to refer a patient for professional mental health care developed gradually rather than at one specific moment, and this decision was made within the context of risk and protective factors. When judging timing and context, respondents relied on their experience with other patients, who served as a reference standard and on personal considerations.

Risk and protective factors

Respondents mentioned several factors associated with risk for emotional problems that require professional mental health care, or conversely, protect patients from problems. The absence of a protective factor was frequently seen as a risk factor, and vice versa. We categorized these as personal, social, and disease- and treatment-related factors.

Personal factors

Personal risk factors included a history of emotional problems, such as earlier treatment by a psychologist, a previous episode of burnout, depression, or emotional problems due to an interpersonal conflict. Respondents suspected that such factors predisposed patients to cancer-related emotional problems.

Respondents mentioned specific character traits as risk or protective factors for emotional problems. They reported that professional mental health care is more often needed when patients are generally anxious or hyperactive, tend to worry, or tend to need to keep everything under control. Respondents expected patients to be better able to handle their emotions when they were generally calm, optimistic, or realistic. Some respondents also mentioned that a positive sign is the overall motivation of a patient, for example toward their treatment or toward maintaining a healthy lifestyle.

Social factors

Respondents highlighted the importance of patients’ social support system and regarded a good social support system as a protective factor. When patients are surrounded by friends or family with whom they have good, stable relationships and who provide support, respondents felt that professional mental health care was less likely to be needed. Conversely, respondents mentioned a weak social support system as a risk factor and suspected that patients would have difficulty handling their emotions without close friends or family, if there was tension or conflict with friends or family, or when others in their social circle were also having a difficult time.

Disease- and treatment-related factors

Disease or treatment that was comparatively stressful was considered by respondents a risk factor for emotional problems. These included long or rapid disease trajectories, a relatively stressful treatment, extreme side effects, acute health problems, or comorbidity. Respondents believed that these types of adverse situations are difficult to adapt to and could eventually lead to a need for professional mental health care.

Indicators for referral

Respondents reported that specific characteristics of emotions and a negative impact of emotions were indicators for referral to professional mental health care.

Characteristics of emotions

Patients were referred to professional mental health care when respondents noticed specific emotional characteristics. These included lingering emotions such as persisting anxiety, anger, sadness, or stress. Some respondents also referred patients if they gradually became more emotional over time. A decreasing intensity of emotions was regarded as a sign of good mental health.

Referral of patients was often prompted when the intensity of emotions was considered disproportionate to the patient’s situation. Descriptions of disproportionate emotions included intense depressive feelings, excessive crying or sadness, extreme panic, severe anxiety, or experiencing many different emotions concurrently. Some respondents emphasized that intense emotions were to be expected in a stressful situation and that these did not immediately require a referral for professional mental health care. Emotions were also considered disproportionate when patients showed little or no emotion in a stressful situation.

Negative impact of emotions

Respondents mentioned weighing the impact of emotions on a patient’s daily life and activities. Examples of indicators for referral included sleep problems due to anxiety and emotions that prohibit patients from reintegrating into daily life or engaging in activities. Respondents saw reintegration and activities as positive indicators of a patient’s mental health, regardless of the specific activity (work or leisure activities).

Patients were referred to professional mental health care when their emotions appeared to interfere with medical treatment by influencing aspects such as communication and decision-making. Professional mental health care was also considered indicated when patients were felt to be “claiming” medical personnel through behavior such as repeated phone calls to confirm information or decisions.

Finally, respondents mentioned unexplained somatic symptoms as a reason for referral. When physical symptoms could not be explained on medical grounds, respondents were aware that there might be an underlying emotional cause.

Discussion

Oncologists and nurses described a strategy to judge their patients’ professional mental health care needs. This strategy consisted of allowing patients time to adjust to stressful events while monitoring their psychological wellbeing, especially when patients exhibited specific risk factors. If emotional problems were noticed, patients were referred to professional mental health care. This strategy was not explicit; instead, it was an implicit strategy that emerged from the interview data. This strategy can be characterized as “watchful waiting,” i.e., closely monitoring a patient’s condition and only providing treatment when justified by symptoms [13, 29, 30].

Emotions, as such, were not considered a symptom requiring professional mental health care. When patients experienced intense emotions, oncologists and nurses did not immediately make a referral, only referring patients if emotions were considered to constitute a problem. This approach implies that they made a distinction between adaptive and maladaptive emotions [12]. In the field of mental health, emotions are considered essentially adaptive—they help people to adapt to events in their environment, such as the diagnosis and treatment of cancer [16]. Sometimes, emotions become maladaptive, hampering adaptation and leading to significant distress and disability. Emotions are considered maladaptive if they are disproportionally severe or persistent, and if they interfere with functioning [17]. Although oncologists and nurses did not articulate this distinction as such, their clinical behavior implies that they intuitively distinguished between adaptive and maladaptive emotions; that is, distinguishing emotions that don’t require professional mental health care from those that do. Elsewhere, we reported further evidence that respondents make this distinction: oncologists’ and nurses’ notes in the patient file better corresponded to a patient’s experienced need for mental health care than to experienced distress. This suggests that clinicians took notes if they thought emotions were maladaptive and required mental health care, whereas few notes were taken in the case of adaptive emotions that did not justify treatment [31].

Mental health research concerning indicators that distinguish adaptive from maladaptive emotions is in a rather early stage. These indicators can be found in various research areas, including emotional dynamics [32], emotion regulation [33], life goals, and subjective well-being [34], as well as the network theory on mental disorders [35]. In the field of psycho-oncology, distinguishing between adaptive and maladaptive emotions is a rather novel concept [12, 36]. The dominant opinion at present is that intense emotions need to be treated [37]. In contrast, our study shows that oncologists and nurses consider emotions to be a normative aspect of the diagnosis and treatment of cancer (see also [18]). Emotions were considered problematic only if emotions lingered, increased over time, or were disproportionately intense, with a negative impact on a patient’s daily life or treatment. This novel and helpful information can be used to develop operational indicators to help distinguish those patients who need professional mental health care.

The risk and protective factors for emotional problems found in this study are generally in line with empirical literature. All factors reported by our respondents are supported by empirical evidence – a history of emotional problems, specific character traits, the quality of the social support system, and disease- and treatment-related factors [38,39,40,41,42]. Apparently, clinical experience and/or formal training have led to a good understanding of risk and protective factors among our respondents. However, the literature also includes evidence for other factors that were not mentioned by our respondents, such as sleep disturbance as a risk factor for emotional disorders [38].

A number of methodological issues need to be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, two levels of data can be distinguished in the current study: the clinician level (oncologists and nurses) and the patient level. The fourteen contributing clinicians varied in gender, age, clinical experience, and academic or teaching hospital setting, as well as in participation in courses or training concerning the psychosocial well-being of patients. Although this group of oncologists and nurses was diverse, it cannot be excluded that other clinicians would have mentioned additional themes (in other words, at the clinician level we can’t confirm that data saturation was achieved). Further research among oncologists and nurses is therefore indicated. At the patient level, 75 patients were purposefully selected to vary in cancer diagnosis, gender, and age. Data saturation was achieved at this level. Second, we used the “think aloud” method to describe how clinicians judge the need for professional mental health care in patients with cancer. This study did not allow conclusions about how consistently this approach was applied. It is quite conceivable that in a busy practice, it is not always possible to consistently assess all patients. Moreover, clinicians likely differ in their approach, and while some may be interested and experienced in judging the need for professional mental health care, others may be less interested or experienced. Taking a broader view, another factor worth considering is that clinicians in different countries may vary in their approach, reflecting differences in clinical practice from country to country. Further research in more countries is needed in order to determine to which extent clinicians make use of the strategy, the risk and protective factors, and the indicators of emotional problems described here. Both intra- and inter-clinician differences should be evaluated. Third, a range of measures was taken in order to ensure the trustworthiness of data [27]. Regarding reflexivity: the researcher documented theoretical and methodological decisions and their rationale, as well as decisions regarding the analysis. Decisions were based on a critical discussion with the supervising team. With regard to credibility: we applied researcher triangulation, and the oncologists and nurses applied purposive sampling to select a variety of patients based on age and gender. However, this may have introduced bias, as oncologists and nurses relied on memory to select patients. A summary of the interviews was not returned to participants to check for accuracy (member check), due to clinicians’ busy schedules. With regard to transferability: our sample was diverse, at both the clinician and patient levels, and we described the relevant characteristics of departments, clinicians, and patients (thick description). With regard to dependability and audit trails: data collection and data analysis occurred in an iterative manner, and we provided a detailed account of the various steps of the study.

Current recommendations regarding the management of emotions in patients with cancer involve distress screening and providing a referral for psychosocial care if needed [37]. Unfortunately, screening and referral programs have shown a limited effect on the psychological well-being of patients [13, 43]. As an alternative to screening and referral, it has been suggested that oncologists and nurses can play an important role in the management of patients’ emotions and the identification of patients in need of professional mental health care [12, 15]. The results of the present study provide preliminary support for this idea. The reported strategy of watchful waiting, the risk and protective factors, and the indicators of emotional problems that require professional mental health care are commensurate and appropriate. However, further development and evaluation of this approach is certainly required. Assuming that not all clinicians are currently able to provide adequate clinical judgment, additional training and organizational measures may help these clinicians improve. Research findings and patient perspectives in the field of mental health could also be integrated into training, to help further improve clinical judgment. Case findings by clinicians could be further improved by repeated assessment of psychosocial needs, and assessment of psychosocial needs could itself be embedded within broader symptom assessments [15].

In conclusion, this study identified the strategy, risk and protective factors, together with the indicators of emotional problems used by oncologists and nurses when judging the need for professional mental health care in patients with cancer. The findings suggest that oncologists and nurses can play an important role in the identification of patients in need of professional mental health care.

Data availability

The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

Braamse AM, van Meijel B, Visser O, Huijgens PC, Beekman AT, Dekker J. Distress, problems and supportive care needs of patients treated with auto- or allo-SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49(2):292–8.

Braamse AM, van Meijel B, Visser OJ, Huijgens PC, Beekman AT, Dekker J. Help-seeking behaviour of patients with haematological malignancies treated with autologous stem cell transplantation. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2016. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12454.

Clover KA, Mitchell AJ, Britton B, Carter G. Why do oncology outpatients who report emotional distress decline help? Psychooncology. 2015;24(7):812–8.

Law E, Levesque JV, Lambert S, Girgis A. The “sphere of care”: a qualitative study of colorectal cancer patient and caregiver experiences of support within the cancer treatment setting. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0209436.

Nakash O, Levav I, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Andrade LH, Angermeyer MC, Bruffaerts R, Caldas-de-Almeida JM, Florescu S, de Giovann G, et al. Comorbidity of common mental disorders with cancer and their treatment gap: findings from the World Mental Health Surveys. Psychooncology. 2014;23(1):40–51.

Suppli NP, Johansen C, Christensen J, Kessing LV, Kroman N, Dalton SO. Increased risk for depression after breast cancer: a nationwide population-based cohort study of associated factors in denmark, 1998–2011. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(34):3831–9.

Dekker J, Braamse A, van Linde ME, Voogd AC, Beekman A, Verheul HM. One in three patients with cancer meets the criteria for mental disorders: what does that mean? J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(25):2826–8.

Tuinman MA, Gazendam-Donofrio SM, Hoekstra-Weebers JE. Screening and referral for psychosocial distress in oncologic practice: use of the Distress Thermometer. Cancer. 2008;113(4):870–8.

Baker-Glenn EA, Park B, Granger L, Symonds P, Mitchell AJ. Desire for psychological support in cancer patients with depression or distress: validation of a simple help question. Psychooncology. 2011;20(5):525–31.

Clover K, Kelly P, Rogers K, Britton B, Carter GL. Predictors of desire for help in oncology outpatients reporting pain or distress. Psychooncology. 2013;22(7):1611–7.

Funk R, Cisneros C, Williams RC, Kendall J, Hamann HA. What happens after distress screening? Patterns of supportive care service utilization among oncology patients identified through a systematic screening protocol. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(7):2861–8.

Dekker J, Karchoud J, Braamse AMJ, Buiting H, Konings I, van Linde ME, Schuurhuizen C, Sprangers MAG, Beekman ATF, Verheul HMW. Clinical management of emotions in patients with cancer: introducing the approach “emotional support and case finding.” Transl Behav Med. 2020;10(6):1399–405.

Schuurhuizen C, Braamse AMJ, Beekman ATF, Cuijpers P, van der Linden MHM, Hoogendoorn AW, Berkhof H, Sommeijer DW, Lustig V, Vrijaldenhoven S, et al. Screening and stepped care targeting psychological distress in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: the TES cluster randomized trial. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17(8):911–20.

Whitney RL, Bell JF, Bold RJ, Joseph JG. Mental health needs and service use in a national sample of adult cancer survivors in the USA: has psychosocial care improved? Psychooncology. 2015;24(1):80–8.

Dekker J, Graves KD, Badger TA, Diefenbach MA. Management of distress in patients with cancer-are we doing the right thing? Ann Behav Med. 2020;54(12):978–84.

Frijda NH. The emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1986.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

Granek L, Nakash O, Ariad S, Shapira S, Ben-David M. Oncologists’ identification of mental health distress in cancer patients: strategies and barriers. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2018;27(3):e12835.

Granek L, Nakash O, Ariad S, Shapira S, Ben-David M. Mental health distress: oncology nurses’ strategies and barriers in identifying distress in patients with cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2019;23(1):43–51.

Willig C: Introducing Qualitative Research In Psychology: Open University Press; 2013.

Van Someren MW, Barnard YF, Sandberg JAC. The think aloud method: a practical approach to modelling cognitive. London: Academic press; 1994.

Ericsson KA, Simon HA: Protocol Analysis: Verbal Reports as Data: The MIT Press; 1993.

Ahmed N, Bestall JC, Payne SA, Noble B, Ahmedzai SH. The use of cognitive interviewing methodology in the design and testing of a screening tool for supportive and palliative care needs. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(6):665–73.

Bowen GA. Grounded Theory and Sensitizing Concepts. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5:12–23.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Green J, Willis K, Hughes E, Small R, Welch N, Gibbs L, Daly J. Generating best evidence from qualitative research: the role of data analysis. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2007;31(6):545–50.

Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ. Thematic analysis:striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16(1):1609406917733847.

Dekker J, de Groot V. Psychological adjustment to chronic disease and rehabilitation - an exploration. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(1):116–20.

Dictionary [https://www.cancer.gov/]

Braamse AM, van Meijel B, Visser OJ, Boenink AD, Cuijpers P, Eeltink CE, Hoogendoorn AW, van Marwijk KM, van Oppen P, Huijgens PC, et al. A randomized clinical trial on the effectiveness of an intervention to treat psychological distress and improve quality of life after autologous stem cell transplantation. Ann Hematol. 2016;95(1):105–14.

van Linde ME, Braamse AMJ, Collette EH, Hoogendoorn AW, Snoek FJ, Verheul HMW, Dekker J. Clinical assessment of emotions in patients with cancer: diagnostic accuracy compared with two reference standards. Psychooncology. 2020;29(4):775–80.

Houben M, Van Den Noortgate W, Kuppens P. The relation between short-term emotion dynamics and psychological well-being: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2015;141(4):901–30.

Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85(2):348–62.

Klug HJ, Maier GW. Linking goal progress and subjective well-being: a meta-analysis. J Happiness Stud. 2015;16:37–65.

Borsboom D. A network theory of mental disorders. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):5–13.

Dekker J, Karchoud J, Braamse AMJ, Buiting H, Konings I, van Linde ME, Schuurhuizen C, Sprangers MAG, Beekman ATF, Verheul HMW: Clinical management of emotions in patients with cancer: introducing the approach "emotional support and case finding". Transl Behav Med 2020.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network: Guideline Distress Management Version 1.2019. In: NCCN. 2019.

Syrowatka A, Motulsky A, Kurteva S, Hanley JA, Dixon WG, Meguerditchian AN, Tamblyn R. Predictors of distress in female breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;165(2):229–45.

Cook SA, Salmon P, Hayes G, Byrne A, Fisher PL. Predictors of emotional distress a year or more after diagnosis of cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Psychooncology. 2018;27(3):791–801.

Fiszer C, Dolbeault S, Sultan S, Brédart A. Prevalence, intensity, and predictors of the supportive care needs of women diagnosed with breast cancer: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2014;23(4):361–74.

Sales PM, Carvalho AF, McIntyre RS, Pavlidis N, Hyphantis TN. Psychosocial predictors of health outcomes in colorectal cancer: a comprehensive review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40(6):800–9.

Braamse AM, Gerrits MM. van MB, Visser O, van OP, Boenink AD, Cuijpers P, Huijgens PC, Beekman AT, Dekker J: Predictors of health-related quality of life in patients treated with auto- and allo-SCT for hematological malignancies. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47(6):757–69.

Schouten B, Avau B, Bekkering GTE, Vankrunkelsven P, Mebis J, Hellings J, Van Hecke A. Systematic screening and assessment of psychosocial well-being and care needs of people with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3:CD012387.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the medical oncologists and nurses who were willing to participate in this research.

Funding

This study was funded by the Dutch Cancer Society (grant 11839).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception/design: JFK, AJTCMdK, FL, MEvL, ATFB, HMWV, and JD. Provision of study material or patients: MEvL, JMvD, and HMWV. Data analysis and interpretation: JFK, AJTCMdK, FL, MEvL, MAGS, ATFB, HMWV, and JD. Manuscript writing: all authors. Final approval of the manuscript: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The medical ethical committee of VU University Medical Center Amsterdam declared that the study did not fall within the scope of the Medical Research Involving Human Subject Act and that official approval was not required (ref. number 2019–5716).

Consent to participate

All participants consented to participate in this study.

Consent for publication

All participants consented to publish the results.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Henk M.W. Verheul and Joost Dekker contributed equally.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Karchoud, J.F., de Kruif, A.J.T.C.M., Lamers, F. et al. Clinical judgment of the need for professional mental health care in patients with cancer: a qualitative study among oncologists and nurses. J Cancer Surviv 17, 884–893 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-021-01151-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-021-01151-2