Abstract

Purpose

Sexual well-being has been identified as an unmet supportive care need among many individuals with genitourinary (GU) cancers. Little is known about the experiences of using sexual well-being interventions among men and their partners.

Methods

This review was reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and followed a systematic review protocol. Data extraction and methodological quality appraisal were performed, and a narrative synthesis was conducted.

Results

A total of 21 publications (reporting on 18 studies) were included: six randomised control trials, seven cross-sectional studies, three qualitative studies, and five mixed methods studies. Sexual well-being interventions comprised medical/pharmacological and psychological support, including counselling and group discussion facilitation. The interventions were delivered using various modes: face-to-face, web-based/online, or telephone. Several themes emerged and included broadly: (1) communication with patient/partner and healthcare professionals, (2) educational and informational needs, and (3) timing and/or delivery of the interventions.

Conclusion

Sexual well-being concerns for men and their partners were evident from diagnosis and into survivorship. Participants benefited from interventions but many articulated difficulties with initiating the topic due to embarrassment and limited access to interventions in cancer services. Noteworthy, all studies were only representative of men diagnosed with prostate cancer, underscoring a significant gap in other GU cancer patient groups where sexual dysfunction is a prominent consequence of treatment.

Implications for cancer survivors

This systematic review provides valuable new insights to inform future models of sexual well-being recovery interventions for patients and partners with prostate cancer, but further research is urgently needed in other GU cancer populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Genitourinary (GU) cancers are located within the urinary and reproductive systems. The incidence rate of detection is 37.5 per 100,000 individuals affected by prostate cancer, bladder cancer is 11.7, and kidney 7.8, and both penile and testicular are less common at approximately 2 per 100,000 men [1]. Improvements in diagnostic tests and treatment options for GU cancers have improved survival rates [2,3,4,5]. However, all treatment modalities for GU cancers can negatively impact sexual function at some stage in the cancer trajectory, given the invasive nature of treatments [1, 6, 7]. Existing systematic reviews among GU cancer populations [8,9,10,11,12,13] have all identified that patients affected by GU cancer continue to report unmet sexual well-being needs with a lack of support from healthcare professionals.

Despite the well-documented unmet sexual well-being needs in GU patient groups, various interventions are available in cancer services to treat sexual dysfunction. Such interventions include (1) pharmacological treatments such as phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitors, (2) mechanical devices such as vacuum pumps and penile implants, (3) psycho-educational interventions such as couples’ counselling, and (4) education and peer support [14,15,16]. Many individuals affected by GU cancers continue to experience sexual health concerns that negatively impact their physical, social, spiritual, and psychological well-being. When sexual health concerns and needs are not met in routine clinical services, it can lead to a reduction in the patients’ sexual motivation, intimacy, and self-esteem, resulting in partner distress, reduced relationship satisfaction, and a breakdown in communication between the couples [9,10,11, 17, 18].

Several barriers to engaging in sexual well-being interventions and recovery have been identified. Known barriers include (1) reluctance to initiate a conversation with their healthcare professional [19], (2) healthcare professionals report a lack of time to discuss sexual well-being during consultations [20, 21], (3) patients have expressed that if a clinician does not raise the topic during the consult, then it must not be a valid clinical concern [22], and (4) sexual dysfunction is an irreversible result of cancer treatments [14, 23]. Acknowledging these barriers, it is important to understand the experiences of available sexual well-being interventions embedded in a biopsychosocial framework [24, 25]. The biopsychosocial framework is important because it provides a holistic approach to managing sexual well-being and addressing what matters most to patients and their partners [24, 26].

It is imperative to focus on the patient’s perspective when developing and evaluating sexual well-being interventions. Patient-reported measures (PROMs) are tools utilised in clinical practice and research to gain insights from the patient’s perspective [27]. Self-reported measures and qualitative experiences can contribute to understanding the patients’ experiences and expectations of sexual well-being interventions and provide important insights into contemporary barriers and facilitators in different healthcare contexts to addressing sexual well-being concerns [28, 29].

This integrative systematic review aimed to understand the experience of sexual well-being interventions in people and their partners affected by GU cancer. Specifically, this review addressed the following clinically focussed research question:

In patients diagnosed with GU cancers, and their partners, what are their experiences of sexual well-being interventions?

Methods

Design

This integrative systematic review has been reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [30]. This review followed a systematic review protocol available upon request.

Search strategy and pre-determined eligibility criteria

The following electronic databases (APA PsycINFO, CINAHL, Cochrane Library (Database of Systematic Reviews and CENTRAL Register of Controlled Trials), MEDLINE, and Scopus) were searched in November 2021. Limiters were applied to the search for date range 1997 onwards and for studies published in English (see Supplementary Table 1 for full record of database searches). Articles were included if they met the following pre-screening eligibility criteria.

Eligibility criteria

Types of studies

Inclusion

Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies irrespective of research design.

Exclusion

Commentaries, editorials, non-peer-reviewed literature, systematic reviews, and non-English studies.

Types of participants

Inclusion

Adults > 18 years diagnosed with GU cancer (and partners) irrespective of time since diagnosis or treatment modality.

Exclusion

Studies conducted with participants with non-GU cancers.

Types of interventions

The interventions included (1) pharmacological therapy such as phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitors and intracavernosal injections—alprostadil, phentolamine, papaverine, intraurethral muse; (2) mechanical devices such as vacuum erectile devices and penile implants; and (3) psychosocial interventions including counselling, and couples counselling, mindfulness, and group therapy.

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcome was the experience of sexual well-being interventions as reported by patients and their partners.

Screening process

All articles identified were imported into Endnote referencing software and exported to Covidence Systematic Review software (Covidence© 2020, version 1517, Melbourne, Australia) for the removal of duplicates and to manage the article screening process. Reviewers applied a pre-eligibility criterion to all titles and abstracts, and any conflicts were resolved by discussion. Full-text articles were reviewed by authors and any disagreements resolved by discussion.

Data extraction

Data were extracted by one review author, and quality was checked by a second reviewer. A data extraction table was developed and piloted on a small number of studies first. The data extraction table contained information in relation to the participants’ clinical and demographic characteristics, setting, sample size, study design, data collection tools, and type of intervention. A second data extraction table was used for the qualitative data (see Supplementary Table 2).

Quality assessment

The methodological quality and evaluation of the studies were assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [31]. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool comprises 25 criteria and two screening questions, and any disagreements in assessment scores were resolved by discussion among the reviewers. This assessment tool was used because it enabled a plethora of research designs to be evaluated.

Data synthesis

This integrative review used the Whittemore and Knafl (2005) methodological approach to evidence synthesis. The data synthesis used an inductive analysis examining the collected data for patterns, similarities, and differences across the included studies [32]. Inductive analysis involved a process of data comparison and drawing and verifying relevant themes from primary sources [33]. The data reduction then was compiled into groups of sexual well-being interventions and data collection tools that evaluated patient experience. Next, the qualitative and quantitative data were synthesised to compare the similarities and differences [33]. The development of conclusions involved judgement decisions of the themes with verification using primary data for accuracy and validation.

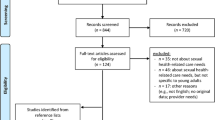

Findings

There were 1131 articles screened, and 21 articles were included in the study (see Fig. 1). Of note, three articles reported on the same study [15, 34, 35], resulting in a total of 18 studies (see Fig. 1). The studies were conducted in a range of countries, which included Australia (n = 3), Brazil (n = 1), Canada (n = 3), Denmark (n = 1), France (n = 1), Netherlands (n = 1), the USA (n = 7), and UK (n = 1). The sample sizes ranged from 6 to 896, with a total sample of 2247 participants included. The participants’ mean age ranged from 60 to 67 years, and the partners’ mean age ranged from 57 to 65 years across the studies. Most participants had completed, at minimum, some form of high school education (Table 1). Noteworthy, all of the included studies were representative only of men with prostate cancer and lacked insights into the sexual well-being intervention experiences among other GU cancer populations.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews, which included searches of databases and registers only. From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71; for more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

The studies included randomised control trials (n = 6), other quantitative studies (n = 5), qualitative studies (n = 2), and mixed methods studies (n = 5). Twelve of these studies involved patients and partners, while five included patients only [20, 22, 35,36,37]. Overall, the methodological quality of the studies was creditable, except for three studies [36, 38, 39] which did not meet all the quality assessment criteria (see Table 2).

There were two main classifications within existing interventional research for sexual well-being, which were either medical or pharmacological (n = 4) and psychological (n = 7). The remaining studies represented the patients’ and intimate partners’ perspectives on sexual well-being interventions (n = 7) [20, 21, 38,39,40,41,42]. All studies represented men diagnosed with prostate cancer treated with surgery, radiotherapy, androgen deprivation therapy, active surveillance, and their partners. Only three studies included representation from same-sex couples. A total of 13 same-sex couples provided insights into their unique needs and preferences for sexual well-being interventions [35, 40, 41]. Two studies [40, 41] investigated what couples wanted in terms of interventions that support sexual recovery [35, 40, 41]. Wootten (2017) developed an online psychological intervention for men with prostate cancer [35, 40, 41].

Qualitative experiences

Overall, three themes emerged which related to (1) communication (with the couple, healthcare professionals, and peer support), (2) educational and informational needs, and (3) timing and delivery of the interventions. In addition, within each of these themes, barriers and facilitators were identified.

Theme 1: Communication

This overarching theme included three sub-themes related to communication between (a) patient and intimate partner, (b) healthcare professionals, and (c) peers. Several studies identified a lack of communication between the couple as an initial barrier to accessing assistance with sexual well-being interventions [21, 34, 40,41,42]. Communication was problematic for couples due to a lack of language knowledge or discomfort with discussing sexual issues. Often, couples relied mainly on non-verbal prompts [41]. The discomfort with discussing sexual issues was a consistent finding in three studies [19, 20, 39]. Couples had trouble in initiating a conversation to discuss intimacy, which compounded further complexities in accessing treatment options for sexual well-being recovery [39]. The issue of communication often led couples to evade the topic and deflect their thinking to other areas of recovery [19].

Communication with healthcare professionals (HCP) was identified as a challenge for patients and partners, particularly discussing sexual health needs [21, 34, 40, 43, 44]. One study [19] reported healthcare professionals also experienced trepidation in initiating the topic of sexual well-being with patients [19]. Patients expressed that the onus was on them to initiate the conversation with healthcare professionals and often felt embarrassed to discuss their sexual concerns [21]. Many patients and partners consequently were left with feelings of stress, frustration, and disappointment [21]. In addition, some patients found healthcare professionals dismissive, assuming older men did not require such information, and patients commented that there was no continuity of care by seeing several doctors in clinic and they had to repeat their sexual issues [20, 21, 40]. Patients described that some healthcare professionals would focus on cancer control rather than directing consultations to the long-term impacts of sexual dysfunction on quality of life [40]. The impacts of sexual dysfunction in gay men’s sexual experiences were often unmet because their experiences were different from heterosexual couples, so healthcare professionals were reticent to engage in a conversation with them [40].

The impact of peer support was valued among patients and their partners [15, 34, 35, 40, 45, 46]. Likewise, peer support was recognised as beneficial in providing the opportunity for patients and partners to discuss and normalise their treatment and sexual well-being recovery [35]. In addition, two studies [15, 40] reported that peer support which provided practical coping advice and assisted with navigating both physical and psychological needs was helpful [15, 40].

Two studies [45, 46] reported the benefits of group peer support interventions. Wittman’s (2013) study involved a one-day retreat with peers and identified that the peer support intervention improved satisfaction between couples for at least six months following the intervention by facilitating open dialogue [46]. The Bossio (2021) study explored a mindfulness group–based intervention. Group interventions allowed patients and their partners to experience acceptance-based communication around intimacy and agreement of a “new sexual normal” [45]. These interventions improved communication between couples and promoted sexual intimacy beyond penetrative intercourse [40].

Several studies [20, 39, 40, 44, 46] identified facilitators which promoted both patient and partner sexual well-being discussions and facilitated communication with healthcare professionals. Enabling open communication with healthcare professionals provided the space to develop a mutual understanding of the expectation of treatments, with realistic expectations of the success of various sexual well-being interventions to minimise the distress of failure [44]. Couples described improved relationship satisfaction when they were given the opportunity to explore different strategies and discuss sexual changes over time [39]. Promoting open, safe, and non-judgemental dialogue between couples and healthcare professionals enabled the timely opportunity to discuss sexual changes. This opportunity provided a positive experience for patients and partners in that their concerns were validated [20, 40].

Theme 2: Educational and informational needs

Several studies [15, 20, 22, 39,40,41] identified barriers to accessing information and education for couples concerning unmet sexual health needs. Patients had difficulty in timely access to healthcare professionals to provide education and information [22, 39]. A lack of informational support was a problem for couples, particularly in the pre- and postoperative phases [20, 40]. Many participants reported a lack of information about the side effects of prostate cancer treatment, specifically regarding the sexual and emotional changes which were likely to occur [20, 40]. Inadequate information led many couples to express frustration, disappointment, and distress which presented a barrier to accessing or using sexual interventions [20, 40, 41]. In contrast, one study [15] reported that patients and partners felt they received copious amounts of information leaving them with feelings of information overload, which was perceived as a barrier [15].

Five studies [15, 39, 45, 47] explored the benefits of providing education for patients and their partners. Findings identified that education should address specific supportive care needs such as self-management of side effects of treatments [15], addressing realistic patients’ expectations [39, 47], and targeting support through education for the couples’ sexual functioning [45]. Two studies [43, 44], using medical interventions (penile prosthesis and intracavernosal injections), identified partner inclusion to be essential in the delivery of sexual healthcare. Including the partner provided support for the couple with a mutual understanding of the intervention and the opportunity to express their concerns [43, 44]. Three studies [35, 41, 46] identified that educational support should focus on couples’ emotions and adaption, which should include grief and loss of their sexual function.

Theme 3: Timing and delivery of interventions

Three studies [21, 38, 40] recommended a structured approach to assessing sexual well-being needs to optimise the timing and access to interventions. Healthcare professionals should explore sexual well-being needs at regular intervals from the point of initial presentation and continue throughout their treatment across the entire cancer care continuum [45]. The timing and delivery of sexual well-being interventions were essential to patients and partners as they required time to assess their needs. Some patients wanted to engage early in their treatment process, whereas others preferred to wait. One patient described that he would like access to a website that has the entire recovery process mapped out, using video, people to talk to, and an outlet for emotional support [40]. Two studies [40, 41] suggested that three months post-treatment was the optimal timing for initiating sexual well-being interventions in the context of their individualised couple-based intervention. These studies suggest that this time point may allow couples to adjust to side effects from treatment and time for the patient to grieve their loss of sexual function [40, 41]. However, O’Brien et al. recommend an individualised approach, with regular psychosexual assessment by healthcare professionals at routine appointments to facilitate timely and accessible sexual well-being recovery interventions [21], underscoring that one size does not fit all [35, 40, 46].

Patients’ experience of participating in sexual well-being interventions

Several studies [35, 41, 45,46,47] reported on interventions to improve or enhance sexual recovery. Sexual side effects from treatment include erectile dysfunction, climacturia (involuntary loss of urine at orgasm), anorgasmia (unable to obtain orgasm), urinary or faecal incontinence, penile shortening, and loss of sexual desire [45]. Sexual recovery involved engaging couples in interventions to improve sexual intimacy. Engaging couples included education and support to encourage effective communication, promote awareness of sexual well-being resources, and provide strategies for coping with the physical and emotional challenges of treatment side effects [35, 41, 45,46,47]. Patients and their intimate partners preferred interventions with a component of peer support and delivered to their individual needs within a suitable time frame [15, 40, 45].

Two broad categories of sexual well-being interventions were identified across the 18 studies. The interventions included medical or pharmacological interventions with the addition of a psychological component [15, 22, 34, 36, 37, 40, 43,44,45,46]. There was a diversity among the interventions regarding composition, timing, and outcomes, and most of the study outcomes focused on erectile function and intervention compliance [15, 34, 37, 44]. The studies included couples’ sexual recovery and satisfaction from the interventions [15, 34, 40, 45, 46].

Erectile function

Several studies reported erectile function using the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) [22, 36, 47] or the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC). The IIEF measure is a 15-item self-report instrument of male sexual function, including sexual desire, satisfaction, erectile function, and orgasm. The score range is between 1 and 25. Severe erectile dysfunction is rated 1–7, moderate 8–12, and mild 17–21 and functional erections are between 22 and 25 [48]. The Naccarato (2016) study indicated that 47% of men had erectile dysfunction in the mild range (14–19) at baseline [22]. A similar finding in Davison’s (2005) cohort (n = 155) indicated an overall score on IIEF (19.98) at baseline which indicated erectile dysfunction [38]. Three studies [40,41,42] utilised the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC). The Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite is a prostate cancer health-related quality of life instrument that measures general symptoms relating to urinary, bowel, sexual, and hormonal issues to provide a comprehensive subjective assessment of patients having treatment for prostate cancer [49]. The scale for erectile dysfunction (ED) using the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite is severe ED (0–33), moderate ED (34–45), mild ED (61–75), and no ED (< 75). Mehta’s (2017) study indicated that men (n = 14) had a mean EPIC score of 20.8 (8.3–53.6) at baseline indicating severe erectile dysfunction [40]. Two studies reported on men preoperatively [41, 42]. The Wittman & Carolan (2015) study (n = 28) reported the average sexual function score on the EDITS was 76.6, indicating that they had mild to no ED. However, a majority of these men used phosphodiesterase to assist the quality of their erections. Similarly, Wittman & Northouse (2015) identified preoperative erectile dysfunction in men (n = 20) experiencing mild ED mean score of 74.4 (SD 25.1). However, this deteriorated to 46.5 (SD 25.1) three months post-surgery which was statistically significant (< 0.0001) [42]. The inability to achieve an erection suitable for penetration following radical prostatectomy is a well-documented symptom. Damage of the cavernous nerves is thought to be a major cause and recovery may take from 18 to 24 months to recover [50].

Partners’ experience

Two studies [43, 44] focused on erectile function and included the partner’s experience. Pillay’s study [43] examined the quality of life, psychological functioning, and treatment satisfaction of men undergoing penile prosthesis insertion following radical robotic prostatectomy. Overall, patients and partners had positive experiences with treatment satisfaction and sexual relationship following penile prosthesis during this intervention [43]. In contrast, Yiou’s (2013) study aimed to investigate the sexual quality of life in women whose partners were using intracavernosal injection therapy. This retrospective longitudinal study investigated men and their female partners one year following radical prostatectomy while men were using penile injections. The women’s sexual life satisfaction significantly correlated with the partners’ response to erectile function (r = 0.41, p < 0.00002) and intercourse satisfaction (r = 0.27, p < 0.005) [44].

Psychological interventions

Four randomised control trials tested sexual well-being interventions on erectile function as the primary outcome and included a psychological component to the interventions [15, 22, 34, 37]. The psychological component was conducted by a clinical psychologist or counselling, which involved a nurse or sexual counsellor or peer support [15, 34]. The psychological intervention consisted of coaching and support for men and their partners either delivered individually or in a group format. At baseline, there were no significant differences in utilisation of treatments for erectile dysfunction (G2 = 1.06); at 12 months post-intervention, there was a meaningful increase in overall use of medical treatments among the groups (G2 = 9.77, p = 0.008). The peer intervention group was 3.14 times and nurse intervention group was 3.67 times more probable to use medical treatments for erectile dysfunction than those in usual care group [15]. Mainly when psychological intervention or counselling support was offered, it promoted better acceptance of sexual well-being interventions [15, 22, 34, 37].

Satisfaction of interventions

Four studies [35, 41, 45, 47] identified that peer and group support interventions had greater sexual satisfaction rates for couples. Sexual satisfaction related to patient’s and partner’s confidence in navigating sexual dysfunction pathways, ease of the sexual conversation, and a focus on the return of intimacy and not just erectile function [35, 41, 45, 47].

Discussion

The sexual well-being interventions identified in this review varied in content and methodology. The interventions were unimodal such as penile injections, phosphodiesterase medication, or penile implants, or multimodal, including the addition of psychological support such as counselling, group therapy, and mindfulness.

Sexual well-being concerns are a prominent unmet need identified throughout the literature [13, 51]. Various barriers to accessing sexual well-being interventions have been noted by patients and their partners and include communication, timely support from healthcare professionals, and consistent support through their cancer continuum [13, 51]. This integrative review examined patients’ and partners’ experiences of accessing sexual well-being interventions. This integrative review has shed light on the paucity of studies in other genitourinary cancers. Sexual well-being has been a significant unmet need in other GU studies in testicular cancer [8], bladder cancer [10], kidney cancer [9], and penile cancer [11]. Although this review aimed to understand the experiences of men and their partners with GU cancers, the literature comprised only prostate cancer studies, which is an important observation.

Despite this review containing entirely prostate cancer studies, sexual health remains one of the most common unmet needs among these patients into survivorship. A publication by Maziego (2020) reported on the long-term unmet supportive care needs of prostate cancer survivors 15 year following diagnosis. The salient findings identified that men find communicating about sexual needs a challenge and particularly gaining healthcare professionals’ help and support was a moderate/severe need [51]. Similar findings have been reiterated within this systematic review identifying communication with healthcare professionals and initiating a conversation about sexual health needs is a barrier for patients.

In developing future sexual well-being interventions, the healthcare professionals must ensure that the patients’ unmet sexual needs are identified and addressed [8, 10]. One recommendation is to address the patients’ unmet needs by completing a biopsychosocial screening at the time of their clinic review. The biopsychosocial screening assesses the patient’s physical, functional, and psychological needs and prioritises the individual’s needs [52]. Identification of patients’ unmet needs early in their cancer care has the potential to provide a more positive outcome in addressing and meeting their needs [51].

Communication with healthcare professionals (HCP) was identified as a challenge for patients and partners, particularly discussing sexual health needs [21, 34, 40, 43, 44].

Healthcare professionals should have a responsibility to engage with patients in sexual health discussions. However, the evidence reveals that they experience barriers such as lack of knowledge and lack of training in this field [54]. A recent review has identified the need for training in sexual health communication for healthcare professionals [54]. The optimal mode of delivery for this education should have a role in both undergraduate and postgraduate programmes, and one option might be in role-play approaches to learning integration [54]. Tertiary education institutions may have a role to improve sexual health communication for healthcare professionals by including training in their core curricula. This will ensure that preparation for the healthcare professional is adequately addressed to assess patients’ sexual needs.

Healthcare professionals and particularly nurses are in the optimal role to ensure that patients can discuss their sexual needs. In addition, it is crucial to maintain open lines of communication and active listening between the healthcare professional, the patient, and the partner. Open communication is fundamental when discussing the potential impact of treatments on their sexual well-being recovery and providing tailored education to patients and partners [5].

An interdisciplinary approach involving partners, peers, and other healthcare professionals by providing information/education evidence-based care will assist in addressing this unmet need. Continual assessment and management of patient’s sexual health concerns at clinical visits will provide timely treatment and evaluation of physical and psychological needs [46, 53].

This review has identified that patients benefited from sexual well-being interventions but many articulated difficulties with initiating the topic with healthcare professionals and timely access to the interventions. In developing strategies to promote timely access to evidence-based information and support, it is crucial to continue to gain an understanding of patient’s experiences and sexual health needs across the cancer continuum and how best healthcare professionals can support them.

Limitations of the study

Although a structured and rigorous process was instigated throughout this integrative review, some limitations were noted. There is first a language bias noted from limiting studies to the English language, and this could mean that some critical studies may not have been included. However, the studies included represented various countries. Several key challenges were identified in this review; the different methodologies used in the studies made the synthesis of evidence challenging. Some studies contained small participant numbers; notably, all the studies involved patients with a diagnosis and treatment for prostate cancer. There was also a deficit in studies involving female GU patients’ experiences. These findings may not extrapolate into other GU cancer groups as the treatment, side effects, and recovery time differ among GU cancers. However, this review has presented an overview of men and their partners’ barriers and facilitators in accessing and using sexual well-being interventions and their experiences in sexual well-being recovery.

Conclusion

This review contributes evidence of sexual concerns of men and their partners from diagnosis, treatment, and into survivorship. It has provided valuable insights into prostate patients’ and partners’ preferences and experiences when accessing or using sexual well-being interventions. Lack of continuity of care and timing of the interventions were identified as important findings. There was an overwhelming paucity in the literature for other GU cancers with sexual well-being interventions and limited representation of the LGBTQ + population. Further research is urgently required in the non-prostate GU cancer population.

Data availability

All generated or analyzed data during this study have been included in this published article.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Sung, H., et al., Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians, 2021. 71(3): p. 209–249.

Canalichio K, Jaber Y, Wang R (2015) Surgery and hormonal treatment for prostate cancer and sexual function. Trans Androl Urol 4(2):103

Carlsson S et al (2016) Population-based study of long-term functional outcomes after prostate cancer treatment. BJU Int 117(6B):E36

Watson E et al (2016) Symptoms, unmet needs, psychological well-being and health status in survivors of prostate cancer: implications for redesigning follow-up. BJU Int 117(6B):E10–E19

Zhu, A. and D. Wittmann. Barriers to sexual recovery in men with prostate, bladder and colorectal cancer. in Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations. 2020. Elsevier.

Bober SL, Varela VS (2012) Sexuality In adult cancer survivors: challenges and intervention. J Clin Oncol 30(30):3712–3719

Tracy M et al (2016) Feasibility of a sexual health clinic within cancer care: a pilot study using qqualitative methods. Cancer Nurs 39(4):E32–E42

Doyle, R., et al., Identifying the unmet supportive care needs of individuals affected by testicular cancer: a systematic review. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 2022: p. 1–25.

O’Dea, A., et al., Identifying the unmet supportive care needs of people affected by kidney cancer: a systematic review. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 2021: p. 1–17.

Bessa A et al (2020) Unmet needs in sexual health in bladder cancer patients: a systematic review of the evidence. BMC Urol 20(1):1–16

Paterson C et al (2020) What are the unmet supportive care needs of men affected by penile cancer? A systematic review of the empirical evidence. Eur J Oncol Nurs 48:101805

Paterson C et al (2015) Identifying the unmet supportive care needs of men living with and beyond prostate cancer: a systematic review. Eur J Oncol Nurs 19(4):405–418

Paterson, C., et al. What are the unmet supportive care needs of people affected by cancer: an umbrella systematic review. in Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 2022. Elsevier.

Barbera L et al (2017) Interventions to address sexual problems in people with cancer. Curr Oncol 24(3):192–200

Chambers SK et al (2015) A randomised controlled trial of a couples-based sexuality intervention for men with localised prostate cancer and their female partners. Psychooncology 24(7):748–756

Gandaglia G et al (2015) Penile rehabilitation after radical prostatectomy: does it work? Trans Androl Urol 4(2):110

Elliott S, Matthew A (2018) Sexual recovery following prostate cancer: recommendations from 2 established Canadian sexual rehabilitation clinics. Sex Med Rev 6(2):279–294

Gordon H, LoBiondo-Wood G, Malecha A (2017) Penis cancer: the lived experience. Cancer Nurs 40(2):E30–E38

Karlsen RV et al (2017) Feasibility and acceptability of couple counselling and pelvic floor muscle training after operation for prostate cancer. Acta Oncol 56(2):270–277

Letts C, Tamlyn K, Byers ES (2010) Exploring the impact of prostate cancer on men’s sexual well-being. J Psychosoc Oncol 28(5):490–510

O’Brien R et al (2011) “I wish I’d told them”: a qualitative study examining the unmet psychosexual needs of prostate cancer patients during follow-up after treatment. Patient Educ Couns 84(2):200–207

Naccarato A et al (2016) Psychotherapy and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor in early rehabilitation after radical prostatectomy: a prospective randomised controlled trial. Andrologia 48(10):1183–1187

Zhu, A. and D. Wittmann, Barriers to sexual recovery in men with prostate, bladder and colorectal cancer. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations, 2020.

Matthew A et al (2018) The prostate cancer rehabilitation clinic: a biopsychosocial clinic for sexual dysfunction after radical prostatectomy. Curr Oncol 25(6):393–402

Wong J et al (2020) Clinic utilization and characteristics of patients accessing a prostate cancer supportive care program’s sexual rehabilitation clinic. J Clin Med 9(10):3363

Wittmann D, Foley S, Balon R (2011) A biopsychosocial approach to sexual recovery after prostate cancer surgery:the role of grief and mourning. J Sex Marital Ther 37(2):130–144

Black, N., Patient reported outcome measures could help transform healthcare. BMJ, 2013. 346.

Venderbos LD et al (2021) Europa Uomo patient reported outcome study (EUPROMS): descriptive statistics of a prostate cancer survey from patients for patients. Eur Urol Focus 7(5):987–994

Meadows KA (2011) Patient-reported outcome measures: an overview. Br J Community Nurs 16(3):146–151

Page, M.J., et al., The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 2021. 10(1).

Hong QN et al (2018) The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf 34(4):285–291

Dwyer PA (2020) Analysis and synthesis. In: Toronto CE, Remington R (eds) A step-by-step guide to conducting an integrative review. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 57–70

Whittemore R, Knafl K (2005) The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs 52(5):546–553

Karlsen RV et al (2021) Couple counseling and pelvic floor muscle training for men operated for prostate cancer and for their female partners: results from the randomized ProCan trial. Sexual Medicine 9(3):100350

Wootten AC et al (2017) An online psychological intervention can improve the sexual satisfaction of men following treatment for localized prostate cancer: outcomes of a randomised controlled trial evaluating My Road Ahead. Psychooncology 26(7):975–981

Miller DC et al (2006) Use of medications or devices for erectile dysfunction among long-term prostate cancer treatment survivors: potential influence of sexual motivation and/or indifference. Urology 68(1):166–171

Nelson CJ et al (2019) Acceptance and commitment therapy to increase adherence to penile injection therapy-based rehabilitation after radical prostatectomy: pilot randomized controlled trial. J Sex Med 16(9):1398–1408

Davison BJ et al (2005) Development and evaluation of a prostate sexual rehabilitation clinic: a pilot project. BJU Int 96(9):1360–1364

Grondhuis Palacios LA et al (2018) Suitable sexual health care according to men with prostate cancer and their partners. Support Care Cancer 26(12):4169–4176

Mehta A et al (2019) What patients and partners want in interventions that support sexual recovery after prostate cancer treatment: an exploratory convergent mixed methods study. Sex Med 7(2):184–191

Wittmann D et al (2015) What couples say about their recovery of sexual intimacy after prostatectomy: toward the development of a conceptual model of couples’ sexual recovery after surgery for prostate cancer. J Sex Med 12(2):494–504

Wittmann D et al (2015) A pilot study of potential pre-operative barriers to couples’ sexual recovery after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. J Sex Marital Ther 41(2):155–168

Pillay B et al (2017) Quality of life, psychological functioning, and treatment satisfaction of men who have undergone penile prosthesis surgery following robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. J Sex Med 14(12):1612–1620

Yiou R et al (2013) Sexual quality of life in women partnered with men using intracavernous alprostadil injections after radical prostatectomy. J Sex Med 10(5):1355–1362

Bossio JA, Higano CS, Brotto LA (2021) Preliminary development of a mindfulness-based group therapy to expand couples’ sexual intimacy after prostate cancer: a mixed methods approach. Sex Med 9(2):100310

Wittmann, D., et al., A one-day couple group intervention to enhance sexual recovery for surgically treated men with prostate cancer and their partners: a pilot study. Urologic Nursing, 2013. 33(3).

Schover LR et al (2012) A randomized trial of internet-based versus traditional sexual counseling for couples after localized prostate cancer treatment. Cancer 118(2):500–509

Rosen RC et al (1997) The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology 49(6):822–830

Wei JT et al (2000) Development and validation of the expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology 56(6):899–905

Mulhall JP et al (2010) Erectile function rehabilitation in the radical prostatectomy patient. J Sex Med 7(4):1687–1698

Mazariego, C.G., et al., Fifteen year quality of life outcomes in men with localised prostate cancer: population based Australian prospective study. BMJ, 2020. 371.

Olver I et al (2020) Supportive care in cancer—a MASCC perspective. Support Care Cancer 28(8):3467–3475

Chambers SK et al (2019) Five-year outcomes from a randomised controlled trial of a couples-based intervention for men with localised prostate cancer. Psychooncology 28(4):775–783

Albers LF et al (2020) Can the provision of sexual healthcare for oncology patients be improved? A literature review of educational interventions for healthcare professionals. J Cancer Surviv 14:858–866

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions Supported by an Australian and New Zealand Urogenital and Prostate Cancer Trials Group (ANZUP) Research Scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kathryn Schubach: conceptualisation, methodology, validation, screening, data extraction, formal analysis, interpretation, writing and original draft. Theo Niyonsenga: supervision, methodology, interpretation, proof-reading the manuscript. Murray Turner: literature writing searches, writing and original draft. Catherine Paterson: conceptualisation, methodology, validation, screening, data extraction, formal analysis, interpretation, writing and original draft, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Podium presentation of this work was presented at the British Association of Urology Nurses Annual Conference in November 2022 and was awarded the Best Oral Presentation.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schubach, K., Niyonsenga, T., Turner, M. et al. Experiences of sexual well-being interventions in males affected by genitourinary cancers and their partners: an integrative systematic review. Support Care Cancer 31, 265 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-07712-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-07712-8