Abstract

Goals of work

The goal of this study was to evaluate, at a population level, the association between specialized palliative care services (SPCS) and short- and long-term caregiver outcomes.

Patients and methods

The Health Omnibus Survey, a face-to-face survey conducted annually in South Australia since 1991, collects health-related data from a rigorously derived, representative sample of 4,400 households. This study included piloted questions in the 2001, 2002, and 2003 Health Omnibus Survey on the impact of SPCS. Sample size was 9,088 individuals. “Unmet needs,” a short-term outcome relevant to the caregiving period during a life-limiting illness, were tallied. “Moving on,” a long-term caregiver-defined outcome reflecting the caregiver’s adaptation and return to a new equilibrium after the death, was assessed with and without SPCS.

Results

Thirty-seven percent (3,341) indicated that someone close to them had died of a terminal illness in the preceding 5 years, of whom 949 (29%) reported that they provided care. SPCS were involved in caring for 60% of deceased patients. Day-to-day caregivers indicated fewer unmet needs when SPCS were involved (p = 0.0028). More caregivers were able to “move on” with their lives when SPCS were involved than when SPCS were not involved (86 vs 77%, p = 0.0016); this effect was greatest in the first 2 years after the loved one’s death.

Conclusion

At a population level, SPCS were associated with meaningful improvements in short-term (“unmet needs”) and long-term (”moving on”) caregiver-defined outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the more than 7,300 specialized palliative-care services (SPCS) internationally [6], a variety of models of service delivery are in place [42]. A common model of SPCS relies on trained specialist providers, whose work is largely in palliative care; in this model, coordination of care occurs wherever the patient is located.

To date, evaluation of SPCS has been difficult [1, 28]. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that SPCS had a positive impact on patients’ pain, other symptoms, and caregiver satisfaction. Evidence is lacking for other caregiver outcomes, or for economic benefit to justify the community’s healthcare investment in these services [31].

Palliative care is person-centered care that focuses on optimizing function and comfort in the setting of life-limiting illness. The patient, family member(s), and informal caregiver(s) comprise the “unit of care.”

SPCS must be judged by their net health impact not only on the patient but also on caregivers including short-term (while the individual performs the functions of caregiver) and long-term (once the role has ceased) outcomes [14]. There are extensive demands on informal caregivers serving patients with life-limiting illness; the caregiver burden encompasses physical, emotional, financial, existential, and social responsibilities [2, 20, 53]. Many caregivers perform a variety of roles, and those with a larger number of roles exhibit greater caregiver strain [33]. Caregiving may compromise health and is associated with premature mortality long after the death of the patient [9, 47, 50, 56, 58]. Depression and restriction of activities are common among caregivers [5, 22, 66]. Caregiver outcomes depend upon a host of variables including gender, age, socioeconomic status, living situation, and the type and quality of relationship between the caregiver and the recipient of care [43].

In the short term, SPCS coordinate support and services in an attempt to minimize caregiver distress and respond to unmet needs [40, 59]. “Unmet needs”, defined as needs not being addressed plus needs receiving insufficient attention, can be psychological, social, informational, physical (activities of daily living and household management), existential, legal, or financial [40]. The experience of caregiving has been described in five domains, each of which carries support needs and outcome repercussions; these domains are (1) disrupted schedule, (2) financial problems, (3) lack of family support, (4) loss of physical strength, and (5) caregiver self-esteem [24, 43]. Inadequate support of caregivers may predict financial burden and poorer caregiver health [59]. A summary measure for differences in caregiver outcomes can be the total number of unmet needs [40, 59].

In the intermediate to long term, SPCS programs are designed to facilitate families’ and caregivers’ adjustment to the loss that they have experienced [34]. High-level long-term caregiver outcomes, with which to evaluate these programs, are poorly developed [27, 28, 68]. One such potential caregiver outcome is “moving on.” Inability to “move on” has been identified as a marker of a complicated course for caregivers after the death [50, 51]. Conversely, caregivers often reflect that they are starting to move on with their life at some point after death. Psychiatric and social-work literature defines moving on as establishing a new caregiver-defined equilibrium after having experienced a period of disequilibrium and integrating the potentially life-changing impact of caregiving into one’s new self-perception and life roles in areas including relationships, intimacy, work, and finances [7, 13, 17, 19, 55]. Moving on is not simply “taking up where one left off” [7]; rather, it implies some degree of re-adjustment and integration of the caregiving and bereavement experiences. It may be characterized as returning to a sense of well-being, “reframing,” or “adapting” [53, 54, 65]. Despite the widespread use of the concept, a validated instrument for measuring moving on has not yet been developed. Nonetheless, the concept of enabling a caregiver to move on can be a first approximation of the long-term impact of SPCS on caregivers.

Historically, efforts to assess SPCS’ influence on short- and long-term caregiver outcomes have been limited because of difficulties in identifying a population of caregivers for people with life-limiting illnesses who do not interact with SPCS [2, 41, 63]. For a population-based assessment of SPCS outcomes, the appropriate denominator must include all caregivers for people with life-limiting illnesses, not only those who are referred to SPCS [15, 48]. We have previously described a population-based survey methodology, the South Australian Health Omnibus Survey, for identifying caregivers of people with life-limiting illnesses where SPCS were and were not involved; we used this methodology again in the current study [16].

Figure 1 depicts the conceptual model being tested in this study. Its aims are to determine whether:

-

1.

SPCS meet the short-term needs of caregivers at the time they are providing support for someone with a life-limiting illness; and

-

2.

An association exists between SPCS use and differences in caregiver-defined long-term outcomes in the years after they have completed their role.

The null hypothesis was that SPCS were associated neither with differences in unmet needs nor with caregivers’ ability to move on after bereavement.

Methods

Setting and subjects

South Australia has a population of 1.47 million people [4]. The South Australian government provides funding for SPCS to support general practitioners and community nurses. The programs offered by SPCS in South Australia reflect service structures in the United Kingdom (UK), United States (US), and elsewhere [26, 28, 31, 44]. Services delivered include care for inpatients, hospital consultation, outpatient clinics, and community visits. Patients access SPCS through referral from any source. The primary eligibility criterion is a life-limiting illness; approximately 85% of people referred to SPCS have cancer.

Survey methodology

The data for this survey were collected in the South Australian Health Omnibus Survey, a state government-associated face-to-face health survey conducted annually since 1991 with approximately 3,000 randomly selected respondents each year. The full survey methodology has been detailed elsewhere [16, 67]. Previously, the content and construct validity in palliative care service planning has been validated [16]. The survey has Ethics Committee (aka, Internal Review Board; IRB) approval.

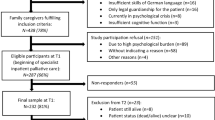

The survey is revised and piloted annually with 50 people using the planned methods for the main survey (Fig. 2). Anonymous face-to-face interviews were conducted by trained interviewers in the respondents’ homes annually during September to November in 2001, 2002, and 2003. A total of 13,200 households across these 3 years were selected for the survey. Metropolitan households were selected in a skip pattern from a randomly selected starting point within 340 Australian Bureau of Statistics collectors’ districts. In nonmetropolitan areas, households were selected using 100 starting points; all towns with a population greater than 10,000 were included, and towns with a population above 1,000 were randomly selected with probability proportional to size. One interview was conducted per household with the person aged 15 or older who most recently had a birthday. Data were double-punched; missing responses were followed up by telephone. Supervisors recontacted 5% of the study population to verify accuracy of the data.

Caregiving was defined for the respondent as follows: “‘Care’ includes attention to any of the needs of the person, including hands-on care, overnight care, respite, shopping, collection of medications, taking to appointments, emotional support, bathing, etc.” To incorporate differing levels of caregiver burden into the analysis, respondents were asked if they provided: “day-to-day hands-on care” (care 5–7 days per week); “intermittent hands-on care” (care 2–4 days per week); or, “rare hands-on care” (care 1 or less days per week). While this method does not encompass information on caregivers’ multiple roles (e.g., parent, employee, spouse, and caregiver), it does stratify respondents along one axis of caregiver burden—the intensity of care provided.

In the 2003 Health Omnibus Survey, a list of response categories was provided to patients to elicit their perceptions of specific unmet needs (Fig. 2). “Unmet needs” were categorized into 14 types of extra support which the respondent felt would have helped him/her as a caregiver; these were selected based on our clinical experience with patients and caregivers in palliative care, the published literature, and pilot testing of the Health Omnibus Survey [40]. These categories map to the five domains of caregiver experience described by Given et al. [24] in the following way: disrupted schedule (better out-of-hours care, respite care); financial problems (financial support/financial planning, legal planning); lack of family support (emotional support for me, emotional support for the person who died, other emotional support, spiritual support, bereavement support); loss of physical strength (support with the physical care of the person who died); and caregiver self-esteem (emotional support for me). Additionally, the study response categories included informational and medical management needs (information about what would happen as the illness progressed, information about services available as the illness progressed, assistance with medications, assistance with physical care and control of symptoms).

Among the 50 pilot respondents in the 2003 survey year, those who answered the respondent-defined moving on question were subsequently asked, “What does the concept of ‘moving on’ mean to you?” Responses were incorporated into the categories for the survey (Fig. 3).

Data analysis

The survey respondents were standardized against the population of all South Australia for gender, 10-year age group, socioeconomic status, and region of residence per the 2001 Australian Census [4] using direct standardization [18] and macros combining multiple survey years obtained from the South Australian Department of Human Services [16, 67]. Each respondent was assigned a standardized weight and only weighted data were analyzed. Annual datasets were compared; there were no statistically significant differences, before combining the datasets, between the years in response rate, demographics, recency of death, deaths due to cancer, family/friend relationship between the respondent and the deceased, or care provided.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize respondent characteristics and responses. Relationships between categorical variables were tested using the chi-square test or chi-square test for trend, as appropriate. Relationships between continuous variables were tested using the Student’s t test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), as appropriate. Two-tailed p values were reported; statistical significance was assumed if p < 0.05. After testing for multi-collinearity (all tolerances >0.9266), variables were entered into a multivariable logistic regression model (PROC LOGISTIC) to determine the factors accounting for categorical caregiver outcomes, or a linear regression model (PROC GLM) with Tukey corrections [10] to determine the factors accounting for continuous outcomes. The Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) statistical package was used for analysis (The SAS System, release 8.02, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Sample size calculation

A sample size requirement was calculated for the comparison of the mean number of unmet needs (“extra supports needed”) among caregivers where SPCS were used vs. SPCS not used. Assuming that a difference in one unmet need was clinically meaningful and a standard deviation of 2.1, then a sample size of 94 caregiver respondents was needed for an alpha 0.05, beta 0.80, and ratio of cases to controls of 0.6 [21]. A sample size requirement was also calculated for the dichotomous comparison of the proportion moving on by use of SPCS. If the baseline rate of moving on was 70% among those who did not use SPCS and an improvement of 10% with SPCS was deemed clinically meaningful (i.e., increased rate of moving on to 80% when SPCS was used), then a sample size of 385 caregiver respondents was needed for an alpha 0.05, beta 0.80, and ratio of cases to controls of 0.60 [21]. Both sample-size expectations were met.

Results

Response rate

Of the 13,200 households approached, the weighted number of respondents was 9,088. The response rate was 70.7% after exclusion of 401 uninhabited houses. Of those approached, reasons given for not responding included refusal (too busy or not interested; 2,006, 15.2%), unable to contact (1,059, 8.0%), respondent unable to speak English (195, 1.5%), selected respondent away for duration of survey (176, 1.3%), illness or mental incapacity precluded participation (173, 1.3%), and terminated interview (6, 0.05%).

Population affected by a death

About 37% of the population (3,340) indicated that someone close to them had “died of a terminal illness like cancer, motor neuron disease, or emphysema” in the preceding 5 years (Table 1). Respondents reporting a death of someone close to them were significantly more likely to be older, married, or widowed, in rural settings, working, and finished with school than those who did not report a death (all p ≤ 0.01).

Caregivers affected by a death

Approximately 10% (949) of respondents (28.4% of people bereaved) identified themselves as caregivers (Table 1) for someone who had died from a life-limiting illness in the past 5 years. When compared to all noncaregivers who reported death of a loved one, caregivers were significantly more likely to be female and widowed (Table 1). About 905 (95.4%) caregivers knew if a SPCS was involved in the care of the deceased individual. Caregivers who knew about SPCS usage were more likely to be close family members (p < 0.0001; chi-square test for trend) but otherwise reported similar patient and caregiver profiles to that of those who “did not know” if SPCS were involved. Subsequent analyses describe the 905 caregivers who knew about SPCS usage.

About 321 of 905 (35.5%) individuals provided day-to-day hands-on care for 5 to 7 days per week; 344 (38.0%) intermittent hands-on care for 2 to 5 days per week; and 240 (26.5%) rare hands-on care for one or less days per week (Table 2). On average, all caregivers provided care for 22.3 (SD 37.2) months, with day-to-day hands-on caregivers providing care for 24.3 (SD 39.9) months, intermittent caregivers for 23.2 (SD 38.9) months, and rare caregivers for 18.2 (SD 30.4) months (p = 0.518; one-way ANOVA).

Use of SPCS

Caregivers reported that SPCS provided support in at least 60% of deaths of terminally-ill people in South Australia (Table 3) and more frequently in people who died of cancer than of noncancer illnesses (84.3 vs. 64.7%, p < 0.0001; chi-square test).

Unmet needs of caregivers while delivering care and the use of SPCS

The relationship between SPCS involvement and additional caregiver supports needed during illness through death was evaluated using the 2003 survey dataset. Approximately 154 (48.1%) caregivers identified that some type of extra support was needed—92 (28.8%) identified physical support needs, 52 (16.3%) information needs, 78 (24.4%) emotional needs, 29 (9.1) financial needs, and 26 (8.1%) other needs—with a mean 1.3 (SD 2.1) extra supports identified per deceased individual. In a linear regression model evaluating the relationship between number of supports needed, level of caregiving, and involvement of a SPCS, involvement of the SPCS helped to predict unmet needs for hands-on caregivers (Fig. 4). For those without SPCS involvement, the number of extra supports needed increased with the level of caregiving (t tests for means; noncaregivers vs rare hands-on caregivers, 0.52 vs. 0.81, p = 0.2433; noncaregivers vs intermittent caregivers, 0.52 vs. 1.56, p < 0.0001; noncaregivers vs day-to-day caregivers, 0.52 vs. 2.35, p < 0.0001); this trend was not noted when SPCS were involved, indicating that caregiver gain, in which unmet needs were addressed, occurred in the context of SPCS. Day-to-day caregivers indicated fewer extra support needs when SPCS were involved in the care of the deceased individual (t tests for means; no SPCS vs. SPCS, 0.95 vs. 2.3, p = 0.0031). The frequency of the top five extra support needs of day-to-day caregivers, by SPCS use or not, is presented in Table 4.

Relationship between the number of categories of additional supports needed during the period of the illness through death, level of care provided, and specialized palliative care service (SPCS) involvement (p = 0.0014 for the interaction of level of care and SPCS). Data from 2003 survey (total of 994 respondents and 314 caregiver respondents). Linear regression model with Tukey corrections (PROC GLM); numbers are least squares means of the number of extra support needs identified by respondents. Vertical bars represent 95% confidence intervals

Impact of SPCS on long-term caregiver outcomes

When SPCS were involved in care, caregivers were significantly more likely to be able to move on with their lives after the death (Table 5; 86.4 vs 77.2%, p for trend = 0.0016). More than 80% of people who used SPCS were able to move on by 1 year, whereas it took 2 years for 80% of people who did not use SPCS to move on (Fig. 5). About 3 years after the death, 10–14% of all caregivers still had not been able to move on.

Predictors of caregivers’ ability to move on

In a multivariable logistic regression model, use of SPCS was positively associated with an ability for caregivers to move on [odds ratio (OR) 0.54, CI 0.36–0.80; Table 6]. This translates to a 46% improvement on the ability to move on when a SPCS is involved. No other factors in the model positively influenced ability to move on.

Predictors of caregivers inability to move on

In a multivariable logistic regression model, caregivers who were unlikely to have “moved on” were significantly more likely to have: had a worse-than-expected experience between diagnosis and death (OR 3.43, CI 1.76–6.68; Table 5); provided day-to-day or intermittent hands-on care (OR 3.72, CI 1.93–7.16, and OR 2.42, CI 1.25–4.69); been in a close family relationship with the deceased (OR 3.34, CI 2.13–5.23); and been bereaved in the preceding 2 years (OR 2.58, CI 1.68–3.97).

Discussion

SPCS are a significant health-system investment. For 30 years, researchers have been working to define the improved outcomes associated with SPCS use [2, 12, 25, 30, 31, 45, 46, 48, 49, 61, 64]. The Health Omnibus data support that SPCS are associated with better meeting of needs for day-to-day hands-on caregivers while in the caregiving role and that SPCS have a subsequent long-term impact in improving a caregiver-defined outcome, moving on.

Finding the whole caregiver population (rather than only those referred to services) has been the dominant challenge in establishing caregiver benefits from SPCS involvement [41]. By using a population-level method [16], this study avoided the bias introduced in studies which only access caregivers through clinicians, case note audits, or registries (clinical or death).

Impact of SPCS on caregivers while in the role

Our study builds on evidence that caregivers providing constant care who accessed SPCS had fewer unmet needs than did an otherwise identical population who did not access SPCS [31]. Considering the five domains of the caregiving experience described by Given et al. [24], family support was the main domain identified as a source of unmet need; the proportion of respondents who identified unmet needs in this domain decreased when SPCS were involved. An additional category of unmet needs important to the caregivers in this study pertained to information needs and help with physical and medical aspects of caring. The largest proportion of identified unmet needs reported were in this category; fewer needs in this category were reported by caregivers of deceased individuals who had SPCS involvement.

Impact of SPCS on caregiver long-term outcomes

SPCS need proactively to minimize the health risks associated with caregiving [23]. Other population approaches have shown associations of benefit with SPCS use in caregiver morbidity and mortality [63]. Christakis and Iwashyna [15] analyzed 31,000 spousal survivors of someone who died from 1 of 13 frequent causes of expected death vs. propensity-matched to controls from the same US Medicare data set. Mortality rates for the surviving spouses were compared 18 months after the death. There was decreased mortality in the group who used SPCS for 24,721 female caregivers (5.4 vs 4.9%, OR 0.92, CI 0.84–0.99) and 6,117 male caregivers (13.7 vs 13.2%, OR 0.95, CI 0.84–1.06). The Omnibus study adds to the work of Christakis by suggesting not only that caregivers who interact with SPCS might have an association with less post-role mortality, but that they may adjust more rapidly to their new life after having been a caregiver.

Like Christakis’ work, this current study cannot attribute a cause-and-effect relationship, although it can demonstrate strength of association. Those willing to access services may have had a better outcome because of problem-focused coping strategies [53].

McCorkle et al. [37] conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) evaluating a home nursing intervention to support palliative caregivers. Despite initial improvement in psychological morbidity of bereaved caregivers in the intervention group, differences that were clinically and statistically significant at 6 and 13 months were no longer apparent by 25 months. Zisook and Shuchter [69] demonstrated that caregivers’ self-rated “adjustment” on a categorical scale showed progressive reductions in the first year. Such patterns are mirrored by our data.

In the McCorkle, Zisook, and Omnibus studies, there is a sizeable group of caregivers who still could not move on after several years. The fact that caregiver distress can last for so long after the death of the person for whom they have cared means that the measurement of service impact demands longitudinal approaches [32, 48, 60].

An RCT from Norway randomized access to SPCS by whole populations in a setting comparable to the current study [54]. The primary outcome for “close family members” (whose level of caring was not clear) was the intensity of grief reactions as measured in the second part of the Texas Revised Inventory of Grief. There was no difference in grief reactions at 13 months in the 183 family members of the 434 patients who were originally enrolled in the study. By contrast, the higher level question, “Have you been able to ‘move on’?” in our study elicited a substantial difference over time between people who did and did not access SPCS. Although moving on constitutes only part of the definition for complicated grief [51] (or prolonged grief reaction), the measured rates of complicated grief in similar populations in the literature appear to be of the same order of magnitude, and at the same time after the death of the care recipient, as the findings from the Omnibus study [11, 39, 52].

Other predictors of caregiver outcomes

Our study supports other broad population-based observations that the intensity of the level of care provided directly correlates with longer-term caregiver outcomes including burden, health, and mortality [57, 59]. The level of caregiving helped to predict both unmet needs and the ability to move on.

One of the strongest predictors of an inability to move on was if the experience from diagnosis to death was “worse than expected;” this finding is consistent with other work in the area [8, 29]. The discrepancy between expectations and what actually happens can amplify feelings of lack of control over a situation. Conversely, a perceived sense of control is known to be related to overall wellbeing [36], and may contribute to an ability to move on.

Limitations to the study

Analysis was limited to the information collected by the South Australian Health Omnibus Survey, a retrospective population-based approach which is dependent upon recollections of bereaved respondents. Methodologically, a prospective study would have been preferable in order to establish potential causal relationships between SPCS and short- and long-term caregiver outcomes; however, it would not be practically feasible to conduct such a prospective controlled research study among caregivers at a population level.

Because the area of caregiving is a relative newcomer to the realm of clinical research, a paucity of robust assessment measures is, as yet, a major limitation of studies in this population. In assessment of short-term caregiver outcomes, we developed a variable to indicate level of intensity of caregiving, which we could link to caregiver strain. We could not encompass in this variable other factors not provided by the 2001–2003 Omnibus dataset, such as roles that caregivers might have been simultaneously performing.Thus, within our measure of caregiver strain defined by intensity of caregiving, we were unable to differentiate those caregivers who performed multiple roles from those who were solely caregivers.

With respect to long-term caregiver outcomes, as noted above, a validated instrument to measure moving on has not yet been developed; in the absence of such a measure, we acknowledge the respondent-defined nature of the concept as utilized in this study. As a first step toward defining this construct, we asked the 50 respondents for the 2003 annual Health Omnibus Survey pilot for input regarding what the concept of moving on meant to them. Results appear in Fig. 3 and provide some initial parameters for development of a measure of this construct.

People who live in remote South Australia and those without caregivers were not represented, and people from some cultural backgrounds may not be seen in these data. All results were based upon the recall of the respondent, which is a validated approach [35, 38, 62]. Caregiver-derived information about the uptake of SPCS is directly derived from first-hand knowledge. Other limitations of the approach have been outlined previously [16].

The programs offered through SPCS and their funding varies widely across the world, making global assessments of the impact of SPCS difficult [3, 15, 42]. This study reflects a variety of palliative care service types ranging from single-nurse-led rural services to large regional metropolitan interdisciplinary programs. These results can be generalized to similar health settings internationally.

Future directions

The relationship between fewer unmet needs and SPCS suggests that SPCS do provide substantial support in helping to plan care and identify contingencies in future care. An understanding of the specific attributes of SPCS that make the most difference in meeting caregivers’ needs will be pursued through future work using similar methods.

Moving on was defined by respondents of a single year of the Health Omnibus Survey; broader validation is planned. Subsequent information will enable evaluation of whether moving on, as a measurable outcome, can be improved. An interesting line of inquiry, which would be made possible by inclusion of a baseline question in a future Health Omnibus Survey, is whether respondents who accessed SPCS were further along in the trajectory of psychological acceptance than were respondents who had not accessed SPCS. A positive correlation might indicate a self-selection bias in which respondents who had used SPCS and who had succeeded in moving on had a predisposition to move on, in comparison to respondents who had not chosen to access SPCS. While of academic interest, this information would not impact the utility of the finding that SPCS facilitated moving on among those individuals who accessed services.

The methodological strength of the approach used in this study, in which we probed data collected via the Health Omnibus Survey to answer a health services question on the population level, could be improved by favorable comparison of data from the Omnibus on caregiver assessment to data collected using a validated caregiver assessment instrument. This step represents a possible future avenue of study but is not yet possible due to the lack of such an instrument.

The relationship between caregivers’ expectations (diagnosis through death) and outcomes will be explored with two subsequent years of data. All results need to be confirmed in other health-delivery systems.

References

Addington-Hall J, Altmann D, McCarthy M (1998) Which terminally ill cancer patients receive hospice in-patient care? Soc Sci Med 46:1011–1016

Addington-Hall J, McCarthy M (1995) Dying from cancer: results of a national population-based investigation. Palliat Med 9:295–305

Ahmedzai SH, Costa A, Blengini C et al (2004) A new international framework for palliative care. Eur J Cancer 40:2192–2200

Anonymous (2004a) 2001 Census Basic Community Profile and Snapshot-South Australia, Vol. 2004. Australian Bureau of Statistics

Anonymous (2004b) The hardest thing I have ever done: A national inquiry in caregivers for people at the end of life. Palliative Care Australia, Canberra, pp 1–72

Anonymous (2005) Summary of hospice and palliative care provision by continent. Hospice Information, London

Arnold EM (1999) The cessation of cancer treatment as a crisis. Soc Work Health Care 29:21–38

Barry LC, Kasl SV, Prigerson HG (2002) Psychiatric disorders among bereaved persons: the role of perceived circumstances of death and preparedness for death. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 10:447–457

Bradley EH, Prigerson H, Carlson MDA et al (2004) Depression among surviving caregivers: does length of hospice enrollment matter? Am J Psychiatry 161:2257–2262

Braun H (1994) Collected works of John W. Tukey, Vol. VIII. Multiple comparisons: 1948–1983. Chapman & Hall, Pacific Grove, CA

Byrne GJ, Raphael B (1994) A longitudinal study of bereavement phenomena in recently widower elderly men. Psychol Med 24(2):411–421

Cameron J, Parkes CM (1983) Terminal care: evaluation of effects on surviving family of care before and after bereavement. Postgrad Med J 59:73–78

Caplan G (1964) Principles of Preventative Psychiatry. Tavistock, London

Christakis NA (2004) Social networks and collateral health effects. Br Med J 329:184–185

Christakis NA, Iwashyna TJ (2003) The health impact of health care on families: a matched cohort study of hospice use by decedents and mortality outcomes in surviving, widowed spouses. Soc Sci Med 57:465–475

Currow DC, Abernethy AP, Fazekas BS (2004) Specialist palliative care needs of whole populations: a feasibility study using a novel approach. Palliat Med 18:239–247

Curry LC, Stone JG (1992) Moving on: recovering from the death of a spouse. Clin Nurse Spec 6:180–190

Curtin L, Klein R (1995) Direct standardization (age-adjusted death rates). In Statistical Notes, no. 6. National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD

Davis CG, Wortman CB, Lehman DR et al (2000) Searching for meaning in loss: are clinical assumptions correct. Death Stud 24:497–540

Devery K, Lennie I, Cooney N (1999) Health outcomes for people who use palliative care services. J Palliat Care 15:5–12

Dupont WD, Plummer WD (1990) Power and sample size calculations: a review and computer program. Control Clin Trials 11:116–128

Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Slutsman J et al (2000) Understanding economic and other burdens of terminal illness: the experience of patients and their caregivers. Ann Intern Med 132:451–459

Ferrario SR, Zotti AM, Ippoliti M et al (2003) Caregiving-related needs analysis: a proposed model reflecting current research and socio-political developments. Health Soc Care Community 11:103–110

Given CW, Given B, Stommel M et al (1992) The Caregiver Reaction Assessment (CRA) for caregivers to persons with chronic physical and mental impairments. Res Nursing Health 15:271–283

Haggmark C, Theorell T, Ek B (1987) Coping and social activity patterns among relatives of cancer patients. Soc Sci Med 25:1021–1025

Hearn J, Higginson IJ (1998) Do specialist palliative care teams improve outcomes for cancer patients? A systematic literature review. Palliat Med 12:317–332

Hearn J, Higginson IJ (1999) Development and validation of a core outcome measure for palliative care: the palliative care outcome scale. Palliative Care Core Audit Project Advisory Group. Qual Health Care 8:219–227

Higginson IJ (1999) Evidence based palliative care. There is some evidence–and there needs to be more. Br Med J 319:462–463

Higginson IJ (2000) The quality of expectation: healing, palliation or disappointment. J R Soc Med 93:609–610

Higginson IJ, Finlay I, Goodwin DM et al (2002) Do hospital-based palliative teams improve care for patients or families at the end of life? J Pain Symptom Manage 23:96–106

Higginson IJ, Finlay IG, Goodwin DM et al (2003) Is there evidence that palliative care teams alter end-of-life experiences of patients and their caregivers? J Pain Symptom Manage 25:150–168

Jepson C, McCorkle R, Adler D et al (1999) Effects of home care on caregivers’ psychosocial status. Image J Nurs Sch 31:115–120

Kim Y, Baker F, Spillers R, Wellisch D (2006) Psychological adjustment of cancer caregivers with multiple roles. Psycho-oncology 15:795–804

Kissane DW, McKenzie DP, Bloch S (1997) Family coping and bereavement outcome. Palliat Med 11:191–201

Klinkenberg M, Smit JH, Deeg DJ et al (2003) Proxy reporting in after-death interviews: the use of proxy respondents in retrospective assessment of chronic diseases and symptom burden in the terminal phase of life. Palliat Med 17:191–201

Luszcz MA (1998) A longitudinal study of psychological changes in cognition and self in late life. Aust Dev Educ Psychol 15:39–61

McCorkle R, Robinson L, Nuamah I et al (1998) The effects of home nursing care for patients during terminal illness on the bereaved’s psychological distress. Nurs Res 47:2–10

McPherson CJ, Addington-Hall JM (2003) Judging the quality of care at the end of life: can proxies provide reliable information? Soc Sci Med 56:95–109

Middleton W, Burnett P, Raphael B, Martinek N (1996) The bereavement response: A cluster analysis. Brit J Psychiatry 169(2):167–171

Morasso G, Capelli M, Viterbori P et al (1999) Psychological and symptom distress in terminal cancer patients with met and unmet needs. J Pain Symptom Manage 17:402–409

Morrison RS (2005) Palliative care outcomes research: the next steps. J Palliat Med 8:13–16

National Consensus Project (2004) Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, Brooklyn, NY, pp 1–67

Nijboer D, Triemstra M, Tempelaar R et al (1999) Determinants of caregiving experiences and mental health of partners of cancer patients. Cancer 86:577–588

Pantilat SZ, Billings JA (2003) Prevalence and structure of palliative care services in California hospitals. Arch Intern Med 163:1084–1088

Parkes CM (1979a) Terminal care: evaluation of in-patient service at St Christopher’s Hospice. Part I. Views of surviving spouse on effects of the service on the patient. Postgrad Med J 55:517–522

Parkes CM (1979b) Terminal care: evaluation of in-patient service at St Christopher’s Hospice. Part II. Self assessments of effects of the service on surviving spouses. Postgrad Med J 55:523–527

Parkes CM, Benjamin B, Fitzgerald RG (1969) Broken heart: a statistical study of increased mortality among widowers. Brit Med J 1:740–743

Parkes CM, Parkes J (1984) ‘Hospice’ versus ‘hospital’ care–re-evaluation after 10 years as seen by surviving spouses. Postgrad Med J 60:120–124

Payne S, Smith P, Dean S (1999) Identifying the concerns of informal carers in palliative care. Palliat Med 13:37–44

Prigerson HG, Bierhals AJ, Kasl SV et al (1996) Complicated grief as a disorder distinct from bereavement-related depression and anxiety: a replication study. Am J Psychiatry 153:1484–1486

Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK (2006) A call for a sound empirical testing and evaluation of criteria for complicated grief proposed by the DSM V. Omega 52:9–19

Prigerson H, Jacobs S (2001) Caring for bereaved patients: “All the doctors just suddenly go". J Amer Med Assoc 286(11):1369–1376

Redinbaugh EM, Baum A, Tarbell S et al (2003) End-of-life caregiving: what helps family caregivers cope? J Palliat Med 6:901–909

Ringdal GI, Jordhoy MS, Ringdal K et al (2001) The first year of grief and bereavement in close family members to individuals who have died of cancer. Palliat Med 15:91–105

Rodgers LS (2004) Meaning of bereavement among older African American widows. Geriatr Nur (Lond) 25:10–16

Schulz R, Beach SR (1999) Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the Caregiver Health Effects Study. J Amer Med Assoc 282:2215–2219

Schulz R, Beach SR, Lind B et al (2001) Involvement in caregiving and adjustment to death of a spouse: findings from the caregiver health effects study. J Amer Med Assoc 285:3123–3129

Schulz R, Newsom J, Mittelmark M et al (1997) Health effects of caregiving: the caregiver health effects study: an ancillary study of the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Behav Med 19:110–116

Sharpe L, Butow P, Smith C et al (2005) The relationship between available support, unmet needs and caregiver burden in patients with advanced cancer and their carers. Psychooncology 14:102–114

Stetz KM, Hanson WK (1992) Alterations in perceptions of caregiving demands in advanced cancer during and after the experience. Hosp J 8:21–34

Strang VR, Koop PM (2003) Factors which influence coping: home-based family caregiving of persons with advanced cancer. J Palliat Care 19:107–114

Tang ST, McCorkle R (2002) Use of family proxies in quality of life research for cancer patients at the end of life: a literature review. Cancer Invest 20:1086–1104

Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V et al (2004) Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. J Amer Med Assoc 291:88–93

Toseland RW, Blanchard CG, McCallion P (1995) A problem solving intervention for caregivers of cancer patients. Soc Sci Med 40:517–528

Vachon ML, Lyall WA, Rogers J et al (1980) A controlled study of self-help intervention for widows. Am J Psychiatry 137:1380–1384

Williamson GM, Shaffer DR, Schulz R (1998) Activity restriction and prior relationship history as contributors to mental health outcomes among middle-aged and older spousal caregivers. Health Psychol 17:152–62

Wilson DH, Wakefield M, Taylor AW (1992) The South Australian Health omnibus survey. Health Promotion J Aust 2:47–49

Yabroff KR, Mandelblatt JS, Ingham J (2004) The quality of medical care at the end-of-life in the USA: existing barriers and examples of process and outcome measures. Palliat Med 18:202–216

Zisook S, Shuchter SR (1986) The first four years of widowhood. Psychiatric Annals 16:288–294

Competing interests

None.

Data Integrity

All authors have had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Complete Funding Declaration

Direct costs of this study were provided through discretionary research funds held by Southern Adelaide Palliative Services, Daw Park, South Australia, Australia with supplemental funding from the Daw House Hospice Foundation, Daw Park, South Australia, Australia (AU$22,500).

Disclaimers

This paper presents original research of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abernethy, A.P., Currow, D.C., Fazekas, B.S. et al. Specialized palliative care services are associated with improved short- and long-term caregiver outcomes. Support Care Cancer 16, 585–597 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-007-0342-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-007-0342-8