Abstract

Background

Serious illness often causes financial hardship for patients and families. Home-based palliative care (HBPC) may partly address this.

Objective

Describe the prevalence and characteristics of patients and family caregivers with high financial distress at HBPC admission and examine the relationship between financial distress and patient and caregiver outcomes.

Design, Settings, and Participants

Data for this cohort study were drawn from a pragmatic comparative-effectiveness trial testing two models of HBPC in Kaiser Permanente. We included 779 patients and 438 caregivers from January 2019 to January 2020.

Measurements

Financial distress at admission to HBPC was measured using a global question (0–10-point scale: none=0; mild=1–5; moderate/severe=6+). Patient- (Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale, distress thermometer, PROMIS-10) and caregiver (Preparedness for Caregiving, Zarit-12 Burden, PROMIS-10)-reported outcomes were measured at baseline and 1 month. Hospital utilization was captured using electronic medical records and claims. Mixed-effects adjusted models assessed survey measures and a proportional hazard competing risk model assessed hospital utilization.

Results

Half of the patients reported some level of financial distress with younger patients more likely to have moderate/severe financial distress. Patients with moderate/severe financial distress at HBPC admission reported worse symptoms, general distress, and quality of life (QoL), and caregivers reported worse preparedness, burden, and QoL (all, p<.001). Compared to patients with no financial distress, moderate/severe financial distress patients had more social work contacts, improved symptom burden at 1 month (ESAS total score: −4.39; 95% CI: −7.61, −1.17; p<.01), and no increase in hospital-based utilization (adjusted hazard ratio: 1.11; 95% CI: 0.87–1.40; p=.41); their caregivers had improved PROMIS-10 mental scores (+2.68; 95% CI: 0.20, 5.16; p=.03). No other group differences were evident in the caregiver preparedness, burden, and physical QoL change scores.

Conclusion

These findings highlight the importance and need for routine assessments of financial distress and for provision of social supports required to help families receiving palliative care services.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Serious illness often causes financial hardship for patients and families in part due to high out-of-pocket co-payments, other medical and non-medical expenses, loss of income secondary to declines in functional status, and inability to maintain employment and health coverage for the patient and similarly, for the primary family caregiver, loss in work productivity and future earnings.1,2,3,4,5 For some families, these additional stressors are on top of a lifetime of poverty that already imposes significant risks of higher morbidity and mortality.6,7,8 Financial hardship, often also referred to as distress, burden, or toxicity, has been examined extensively in patients with cancer. Nearly half of cancer survivors experience financial distress.4 Younger age, female, low income, racial/ethnic minorities, having more comorbidities, and lack of insurance were risk factors associated with financial hardship.9,10,11 Financial distress is in turn associated with poor quality of life,12, 13 depression,12, 14 and increased mortality.15

Beyond cancer, for patients living with advanced illness, Emanuel and colleagues16 identified underlying factors such as old age, low income, poor physical function, and incontinence as being associated with substantial care needs that were primary drivers of economic hardship; they recommended interventions that meet patients’ needs without imposing additional cost or effort on the caregiver. Home-based programs that provide multi-disciplinary services with minimal or no co-payments may help alleviate the hassles and costs of services such as transportation for clinic-based care, especially for patients who are homebound and have significant functional limitations17, 18 though these services do not fully offset other costs.

Home-based palliative care (HBPC) is an interdisciplinary service available to patients with a serious illness and prognosis of 1–2 years who are members of Kaiser Permanente, a large integrated healthcare system.19 Although patients on HBPC may receive concurrent curative care, most families are aligned with the philosophy of prioritizing home-based treatments and supportive services first, rather than hospital-based care.20 HBPC may serve as a bridge to hospice. The purposes of this paper are to describe (1) the prevalence of financial distress as reported by patients or caregivers at admission to HBPC, (2) the characteristics of patients with moderate/severe financial distress and their caregivers, and (3) the relationships between financial distress with patient and caregiver self-reported outcomes and hospital-based utilization after enrolling in HBPC.

METHODS

Design

This study was a secondary analysis of data drawn from a non-inferiority cluster randomized trial to compare two models of HBPC, a standard and tech-supported approach that leveraged remote physician video consultations.21, 22 Patients and family caregivers were recruited from fourteen sites across two Kaiser Permanente regions (Southern California [KPSC] and Oregon/Washington [KPNW]). The study was approved by the KPSC (#11633) and KPNW (#834) Institutional Review Boards. Participant enrollment occurred from January 7, 2019, through January 12, 2020, with follow-up data collection ending on July 9, 2020.

Population

Patients (n=3533) who were 18 and older, living with a serious illness (e.g., cancer, cardiopulmonary diseases), expected to have a prognosis of 1–2 years, homebound, English or Spanish speakers, and admitted to HBPC were included in the trial. A subset of these patients who completed an assessment of financial distress at HBPC admission are included in this analysis (n=779). We identified adult (18+ years or older) caregivers (n=438) by asking the patient during the phone screening, “Who helps you with your care?” or if the patient lacked decisional capacity, through information obtained from the electronic medical records (EMR) on a surrogate decision maker or durable power of attorney.

Home-Based Palliative Care

Patients were eligible for HBPC if their physician estimated a prognosis of 1–2 years, met Medicare guidelines for receipt of home health to include a skilled nursing need, and were homebound. Patients could receive concurrent disease-directed therapy. HBPC was provided by an interdisciplinary team of physicians, nurses, and social workers, supplemented with therapists, home health aides, and chaplains who addressed the bio-psycho-social-spiritual needs of patients and families. The teams assumed a co-management, primary, or mixed role. As patients approached end-of-life, they could remain on HBPC or transition to hospice. Patients who improved or were no longer homebound could transition to outpatient palliative care services.19, 23

Independent Variable

We assessed patient financial distress with a single validated question at admission, “What is your current level of financial distress on a scale of 0 to 10 with 0 being no financial distress and 10 being the worst financial distress,” via the patient or caregiver proxy.24 Patients who scored 1–5 and 6 or more were considered to have mild or moderate/severe financial distress, respectively.

Primary Patient- and Caregiver-Reported Outcomes

We measured patient symptom burden with the total score of the 9-item Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS),24, 25 physical and mental quality of life with the PROMIS-10,26 and general distress with the single-item, 0–10-point distress thermometer.27 We measured caregiver preparedness with the Preparedness for Caregiving Scale (PCS),28, 29 quality of life with the PROMIS-10, and burden with the Zarit-12 Burden Scale.30 These measures were collected at HBPC admission and 1 month later.

Secondary Outcome: Patient Hospital-Based Utilization

All-cause hospital-based utilization (emergency department visits, observation stays, and inpatient) was measured from admission to when the first event occurred, death, or through end of the study period, at which point those patients who experienced neither an event nor death were censored. These data were extracted from the EMR or derived from claims of utilization outside of the health system.

Process Measures and Other Covariates

We obtained patient (e.g., socio-demographics, clinical variables) characteristics from administrative, membership, and clinical or program electronic records. We collected caregiver socio-demographics and caregiving characteristics (relationship, living arrangement, help from others) from surveys. We measured HBPC service use and outpatient primary and specialty care visits from admission to 1 month to correspond with timing of the survey data collection for each patient. Other healthcare utilization prior to and after admission were also obtained from the EMR or claims.

Statistical Analyses

We used linear mixed-effects models to compare adjusted mean change scores in patient and caregiver self-reported measures across financial distress groups, accounting for the respective baseline survey scores with random intercepts. We included the following covariates in the adjusted models for patient surveys (ESAS, general distress, and PROMIS-10) based on prior clinical knowledge and their association with financial distress or the outcome: age, gender, race/ethnicity, admitting diagnosis (cancer vs. non-cancer), and proxy response; since the ESAS could be administered by research or HBPC staff, we also included this indicator in the ESAS model. To address potential outliers, we also compared median change scores in a sensitivity analysis using quantile regression. For changes in caregiver surveys, we included the following patient (age, admitting diagnosis, baseline ESAS score) and caregiver (age, gender, race/ethnicity, and caregiving help from others) covariates.

For time-to-first hospital-based utilization following HBPC admission, we used Fine and Gray’s31 proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk to account for death as a competing risk to utilization and hospice enrollment as a time-varying covariate. We included the following covariates due to their association with financial distress and utilization: age, gender, race/ethnicity, available caregiver, insurance, Charlson co-morbidity index, admitting diagnosis, and any prior year hospitalizations. The a priori threshold for statistical significance was a 2-sided p value <0.05. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Financial Distress: Prevalence and Patient and Caregiver Characteristics

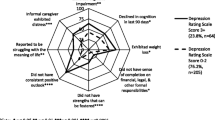

Approximately 50% of patients at admission reported at least some financial distress; 26% experienced moderate/severe financial distress (Table 1). Those who reported moderate/severe financial distress were significantly younger, lived in a census block with lower median household income, had employer-based health insurance, were more likely to receive medical financial assistance, had cancer, and had less functional impairment compared to patients reporting no to mild financial distress. Patients with higher levels of financial distress had worse symptom burden (ESAS), general distress, and quality of life (PROMIS-10) (all, p < 0.001).

For patients with a caregiver enrolled in the study, there were no differences in caregiver socio-demographic characteristics across the financial distress cohorts, other than younger caregiver age in the moderate/severe financial distress cohort (Table 2). Caregivers of patients who had any level of financial distress also reported poorer quality of life, greater burden, and feeling less prepared for caregiving, compared to caregivers of patients with no financial distress (all, p<.01).

Follow-up Data Collection and Use of HBPC and Outpatient Services

Follow-up survey data at 1 month were available for approximately 67% and 53% of the patients and caregivers, respectively. Over a quarter (27%) of the patients who had no follow-up ESAS (n=248) died before the 1-month follow-up assessment. Patients with follow-up data were slightly older with lower Charlson co-morbidity scores, less likelihood to be African American, or more likely to have cancer, but otherwise did not differ on other baseline socio-demographic, clinical, or survey characteristics from those who did not have follow-up data. Follow-up completeness and the number of days patients were on HBPC before the follow-up survey data collection were similar across financial distress groups (Table 3).

Patients with financial distress were more likely to have at least one home or phone visit by a social worker (84% (moderate/severe) vs. 78% (mild) vs. 70% (no)) and more frequent contacts (0.7 vs. 0.6 vs. 0.5 per 10 days, respectively) (Table 3). Frequency of visits from other disciplines was not different across groups. Clinic visits to specialty care were higher than to primary care with no differences in visit frequency across groups.

Financial Distress and Changes in Patient and Caregiver Outcomes 1 Month After HBPC Admission

Compared to the no financial distress group, patients with moderate/severe financial distress had significantly and clinically greater reductions in symptom burden (ESAS: −4.39; 95% CI: −7.61, −1.17; p<.01) and general distress (−0.90; 95% CI: −1.71, −0.10; p=.03) at 1 month after admission in adjusted analyses (Table 4). Reductions occurred in both the ESAS physical and psychological domains and these changes met established minimal clinically important differences (MCID) criteria.32 Median ESAS change scores were slightly smaller (difference-in-differences, DID: −3.49). We found no significant group differences in changes in quality of life. Ratings of financial distress for patients with moderate/severe financial distress dropped by 3.2±3.5 points from admission (8.0±1.4) to 1 month later (4.9±3.6).

Caregivers of patients with moderate/severe financial distress reported improved PROMIS-10 mental well-being at follow-up (+2.68; 95% CI: 0.20, 5.16; p=.03) compared to caregivers of patients with no financial distress at baseline; the median DID was slightly larger (3.4). These differences fall within the range of MCID thresholds (2.3 to 5.5 points) from prior studies.33 There were no significant group differences on preparedness for caregiving, burden, or physical well-being (Table 4).

Financial Distress and Patient Hospital-Based Utilization After HBPC Admission

Nearly two-thirds of patients had at least one hospital-based utilization (ED visit, observation stay, or inpatient admission) and 25% died before having an event during a median follow-up of 2 months (range 0–20 months). Among the 11% who survived until the end of follow-up with no hospital-based utilization, the median follow-up time was 13 months (range 6–18 months). Accounting for the competing risk of dying, the unadjusted model showed that moderate/severe financial distress was associated with a 28% increased risk of having a hospital-based utilization in the months after admission compared to no financial distress (hazard ratio, HR: 1.28, 95% CI: 1.03–1.59, p=.02). However, the adjusted model showed that moderate/severe financial distress was no longer significantly associated with hospital utilization (HR: 1.11, 95% CI: 0.89–1.37, p=.35) (Table 5). Sensitivity analyses were conducted with a subset of patients (n=682) who also had data on receipt of medical financial assistance and level of functional impairment at admission. These models yielded the same results.

DISCUSSION

In a large cohort of patients receiving home-based palliative care in the USA, half experienced at least some level of financial distress. Financial distress was associated with worse patient symptoms and quality of life and family caregiver perception of preparedness, quality of life, and burden. In the 1 month after admission to HBPC, patients with moderate/severe financial distress experienced significantly greater reductions in symptom burden compared to patients with no financial distress. Their caregivers also had greater improvements in mental well-being compared to caregivers of patients with no financial distress. During this short episode of care, patients with moderate/severe financial distress and their families received more support from social workers compared to those with no financial distress which may partly explain the greater improvement in well-being. Finally, baseline financial distress was not associated with risk of hospital-based utilization in the months after admission. These findings together highlight the importance and need for routine assessments of financial distress, as well as the provision of social supports required to help patients and families receiving palliative care services. Moreover, future studies should examine the heterogeneity of palliative care effects according to social factors given the differential changes in symptom burden we observed in this study.34

We relied on a global assessment of financial distress by patients and proxies and were not able to capture specific domains of hardship. However, we did identify that nearly half of the patients (47%) with moderate/severe financial distress received medical financial assistance from the health system. Persistent medical debt could propagate other unmet needs, complicating patients’ and families’ ability to cope with and manage their health.16 Census-level income data also showed that patients with moderate/severe financial distress were more likely to live in neighborhoods with an annual median household income of <$50,000 compared to those with mild or no financial distress. This observation provides further objective validation of patients’ perception of economic hardship.

Similar to previous studies from other countries with national health insurance,35, 36 having health insurance does not shield patients and families from financial distress. We found that patients with moderate/severe financial distress tended to be younger (mean age: 73 vs. 79) than those with mild or no financial distress, consistent with previous studies.9,10,11, 37 Over two-thirds were in pre-retirement (age <65) and likely becoming seriously ill while working, precariously dependent on employer health insurance and public unemployment and disability insurance, as well as having a premature loss of employment income. Since receipt of HBPC did not require co-pays or deductibles and entailed fewer practical hassles related to travel for clinic-based care, HBPC may have been particularly helpful for patients experiencing high physical and emotional symptoms and financial distress; of importance were the notable reductions in financial distress at follow-up for the high distress group. While more Medicare Advantage plans are offering home palliative care as a supplemental benefit,38 it is unclear what level of cost-sharing is required and how that could potentially create an unintended access barrier.

For most patients who enroll in HBPC, their philosophy of care is oriented towards receiving treatments and care in the home. We had hypothesized that those with moderate/severe financial distress may have greater unmet needs over time that could result in increased hospital-based utilization, similar to previous studies that reported greater end-of-life treatment intensity in patients experiencing financial hardship.39 Our finding that moderate/severe financial distress at baseline did not increase the risk of hospital-based utilization suggests that better symptom control and greater social work support in particular may have served as a “buffer.” Social work support likely focused on providing emotional support, connecting families to resources, and/or helping families reconcile goals of care and treatments based on their financial realities. Enrollment in hospice any time after HBPC exposure was a strong predictor of reduced hospital-based utilization.

Limitations

While our sample is larger and more diverse than that of other studies, there are several important limitations. Due to the high rate of proxy response (60%), the reported financial distress likely reflects both the patients’ and caregivers’ perception of hardship. Although previous studies have further classified financial hardship into more granular domains and had data on household income,11 our measure of financial distress was global and we relied on neighborhood level household income. Some of the improvements in the patient- and caregiver-reported outcomes in the moderate/severe financial distress group could be due to regression to the mean or are spurious due to multiple comparisons; the sensitivity analyses comparing median ESAS change scores only account for extreme outliers. Nonetheless, nearly all the self-reported outcomes of the moderate/severe financial distress group at the 1-month follow-up were still higher than of the no financial distress group suggesting remaining disparities as a function of economic hardship. Imputation for the high missingness of survey data was not possible, although baseline characteristics were substantially the same in those who had missing data and those we analyzed. The analyses were also limited by the lack of a control group, not exposed to HBPC, and possibly affected by survival bias with more financially distressed patients not making it to older age.

The caregiver sample was relatively small with inconsistent findings across the four outcomes and thus, the findings should be considered exploratory. We were not able to assess or analyze the nature of the social work support nor the community-based social services that families may have received concurrent with HBPC. This will be especially important for future work to understand the mechanism for how addressing unmet social needs can improve health outcomes for the seriously ill. Finally, our study sample draws from a population of insured patients, receiving care within an integrated delivery system and whose experience with serious illness care may not be broadly generalizable. Having health insurance perhaps mitigated some of the adverse effects of financial hardship observed in previous studies, but having insurance is unlikely to eliminate the distress that comes with limited finances.

CONCLUSIONS

We found that half of the patients receiving HBPC reported financial distress, that more severe financial distress was associated with worse patient- and caregiver-reported outcomes, and that HBPC provided more social work support to families with high financial distress which may have buffered the effects of financial hardship on patient symptoms and hospital-based utilization, as well as caregiver mental well-being. Our findings raise the question of whether prioritizing patients who experience severe financial hardship coupled with high symptoms for home-based care could alleviate overall suffering. More importantly, our findings add to the emerging evidence about how to address the impact of social needs on health and end-of-life care in light of the unprecedented societal disruptions that have manifested during the COVID-19 pandemic.

References

Committee on Family Caregiving for Older Adults; Board on Health Care Services; Health and Medicine Division; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Schulz R, Eden J. editors. Families caring for an aging America. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2016 Nov 8. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK396401/, https://doi.org/10.17226/23606.

Wolff JL, Spillman BC, Freedman VA, Kasper JD. A national profile of family and unpaid caregivers who assist older adults with health care activities. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176(3):372-379.

Gardiner C, Brereton L, Frey R, Wilkinson-Meyers L, Gott M. Exploring the financial impact of caring for family members receiving palliative and end-of-life care: A systematic review of the literature. Palliat Med 2014;28(5):375-390.

Altice CK, Banegas MP, Tucker-Seeley RD, Yabroff KR. Financial hardships experienced by cancer survivors: A systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst 2017;109(2).

Essue BM, Beaton A, Hull C, et al. Living with economic hardship at the end of life. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015;5(2):129-137.

Gill TM, Zang EX, Murphy TE, et al. Association between neighborhood disadvantage and functional well-being in community-living older persons JAMA Intern Med 2021.

Chokshi DA. Income, poverty, and health inequality. JAMA. 2018;319(13):1312-1313.

Chetty R, Stepner M, Abraham S, et al. The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001-2014. JAMA. 2016;315(16):1750-1766.

Han X, Zhao J, Zheng Z, de Moor JS, Virgo KS, Yabroff KR. Medical financial hardship intensity and financial sacrifice associated with cancer in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol, Biomarkers Prev: A publ Ame Assoc Cancer Res, cosponsored Ame Soc Prev Oncol 2020;29(2):308-317.

Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP, Jr., et al. Financial hardship associated with cancer in the United States: findings from a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors. J clin oncol : Official J Ame Soc Clin Oncol 2016;34(3):259-267.

Zheng Z, Jemal A, Han X, et al. Medical financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer. 2019;125(10):1737-1747.

Kale HP, Carroll NV. Self-reported financial burden of cancer care and its effect on physical and mental health-related quality of life among US cancer survivors. Cancer. 2016;122(8):283-289.

Fenn KM, Evans SB, McCorkle R, et al. Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors’ quality of life. J oncol prac 2014;10(5):332-338.

Chan RJ, Gordon LG, Tan CJ, et al. Relationships between financial toxicity and symptom burden in cancer survivors: A systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manag 2019;57(3):646-660.e641.

Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J clin oncol : Official J Ame Soc Clin Oncol 2016;34(9):980-986.

Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Slutsman J, Emanuel LL. Understanding economic and other burdens of terminal illness: The experience of patients and their caregivers. Ann Intern Med 2000;132(6):451-459.

Totten AM, White-Chu EF, Wasson N, et al. Home-Based Primary Care Interventions [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2016 Feb. (Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, No. 164.) Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK356253/.

Leff B, Lasher A, Ritchie CS. Can home-based primary care drive integration of medical and social care for complex older adults? J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67(7):1333-1335.

Brumley R, Enguidanos S, Jamison P, et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: Results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55(7):993-1000.

Wang SE, Liu IA, Lee JS, et al. End-of-life care in patients exposed to home-based palliative care vs hospice only. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67(6):1226-1233.

Nguyen HQ, Mularski RA, Edwards PE, et al. Protocol for a noninferiority comparative effectiveness trial of home-based palliative care (HomePal). J Palliat Med 2019;22(S1):20-33.

Nguyen HQ, McMullen C, Haupt EC, Wang SE, Werch H, Edwards PE, Andres GM, Reinke L, Mittman BS, Shen E, Mularski RA. Findings and lessons learnt from early termination of a pragmatic comparative effectiveness trial of video consultations in home-based palliative care. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020 Oct 13:bmjspcare-2020-002553. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002553.

Brumley RD, Enguidanos S, Cherin DA. Effectiveness of a home-based palliative care program for end-of-life. J Palliat Med 2003;6(5):715-724.

Delgado-Guay MO, Chisholm G, Williams J, Frisbee-Hume S, Ferguson AO, Bruera E. Frequency, intensity, and correlates of spiritual pain in advanced cancer patients assessed in a supportive/palliative care clinic. Palliat Support Care 2016;14(4):341-348.

Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Mcacmillan K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): A simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care 1991;7:6-9.

Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, Spritzer KL, Cella D. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res 2009;18(7):873-880.

Graves KD, Arnold SM, Love CL, Kirsh KL, Moore PG, Passik SD. Distress screening in a multidisciplinary lung cancer clinic: Prevalence and predictors of clinically significant distress. Lung Cancer 2007;55(2):215-224.

Archbold PG, Stewart BJ, Greenlick MR, Harvath T. Mutuality and preparedness as predictors of caregiver role strain. Res Nurs Health 1990;13(6):375-384.

Schumacher KL, Stewart BJ, Archbold PG. Mutuality and preparedness moderate the effects of caregiving demand on cancer family caregiver outcomes. Nurs Res 2007;56(6):425-433.

Bedard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, Dubois S, Lever JA, O’Donnell M. The Zarit Burden Interview: a new short version and screening version. Gerontologist. 2001;41(5):652-657.

Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999;94:496-509.

Hui D, Shamieh O, Paiva CE, et al. Minimal clinically important difference in the physical, emotional, and total symptom distress scores of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System. J Pain Symptom Manag 2016;51(2):262-269.

PROMIS. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System. https://www.healthmeasures.net/score-and-interpret/interpret-scores/promis/meaningful-change.

Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, et al. Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(20):2104-2114.

Barbaret C, Delgado-Guay MO, Sanchez S, et al. Inequalities in financial distress, symptoms, and quality of life among patients with advanced cancer in France and the U.S. Oncologist 2019;24(8):1121-1127.

Barbaret C, Brosse C, Rhondali W, et al. Financial distress in patients with advanced cancer. PLoS One 2017;12(5):e0176470.

Covinsky KE, Goldman L, Cook EF, et al. The impact of serious illness on patients’ families. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatment. JAMA. 1994;272(23):1839-1844.

Crook H, Olson A, Alexander M, et al. Improving Serious Illness Care in Medicare Advantage: New Regulatory Flexibility for Supplemental Benefits 2019; https://healthpolicy.duke.edu/sites/default/files/atoms/files/dukereport_supplementalbenefits_for_final_signoff.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2020.

Tucker-Seeley RD, Abel GA, Uno H, Prigerson H. Financial hardship and the intensity of medical care received near death. Psychooncology. 2015;24(5):572-578.

Acknowledgements

The authors are greatly appreciative of the HomePal study participants, the entire HomePal Research Group, which includes investigators, clinical partners, and staff from Kaiser Permanente Southern California and Kaiser Permanente Northwest, consultants, stakeholder advisory committee members, and members of the data and safety monitoring board:

Funding

This work was supported through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (PLC-1609-36108).

Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Pasadena, CA, USA: Huong Nguyen, PhD, RN, Ernest Shen, PhD, Brian Mittman, PhD, Susan Wang, MD, FAAHPM, Ari Padilla, MBA, Mayra Macias, MS, Eric Haupt, Sc.M, Janet Lee, MS, Thearis Osuji, MPH, Kathleen Estrada, MSN, Rebecca Biddle, RN, BSN, Byron Batz, MS, Jasamin Disney, RN, BSN, Teresa Martinez, RN, BSN, Rose Roxas, RN, BSN, Peter Khang, MD, Dan Huynh, MD, Mary Machado, RN, MSN, Gina Andres, MSW, Angel Vargas, FACHE.

Kaiser Permanente Northwest, Portland, OR, USA: Richard Mularski, MD, MSHS, MCR, Carmit McMullen, PhD, Britta Torgrimson-Ojerio, RN, PhD, Madeline Peyton, MPH, John Brandes, Emily Schield, RN, BSN, Phyllis Ramey, RN, MSN, Chris Carlson, RN, BSN, Paula Edwards, RN, Vicki Krepps, RN, Jennifer Black, MD, Erin Bruner, RN, BSN.

Data Coordinating Center, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, Center for Health Research, Portland, OR, USA: Mary Ann McBurnie, PhD, Ning Smith, PhD, Suzanne Gillespie, MA, MS, Kim Funkhouser, BS, Morgan Fuoco, MA, Dea Papajorgji-Taylor, MA, MPH, Phil Crawford, MS, Kelly Kirk, BS, Joe Cerizo, BA, Kimberly Stewart, MPH, Daniel Vaughn, MS, Meagan Shaw, MA, Katie Vaughn, BA.

Consultants: Joanne Lynn, MD, MA, MS, Lynn Reinke, PhD, RN

Stakeholder Advisory Committee: Charles Anderson, Summer Austin-Bowden, David Baker, MD, MPH, Bill Clark, Janet Corrigan, PhD, MBA, Jennie Chin Hansen, MS, RN, Maureen Henry, JD, PhD, Keung Luke, PhD, Thomas Lee, MD, Carol Levine, MA, Kristine Maberry, Diane Meier, MD, Carol Joy Phillips, Sarah Scholle, DrPH, MPH, June Simmons, MSW, Judy Thomas, JD, Henry Werch.

Data Safety Monitoring Board: Patricia Ganz, MD, Mary Naylor, PhD, Soo Borson, MD, Kevin Cain, PhD.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Key Message

• We assessed characteristics of patients and caregivers with financial distress at admission to home-based palliative care and studied the relationship between financial distress with patient and caregiver outcomes. Financially distressed patients had worse symptoms and caregiver burden at admission. Routine assessments of financial hardship and provision of social resources are essential for palliative care programs.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, S.E., Haupt, E.C., Nau, C. et al. Association Between Financial Distress with Patient and Caregiver Outcomes in Home-Based Palliative Care: A Secondary Analysis of a Clinical Trial. J GEN INTERN MED 37, 3029–3037 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07286-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07286-3