Abstract

Background

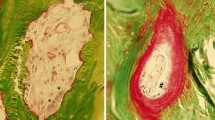

With declining kidney function and therefore increasing plasma oxalate, patients with primary hyperoxaluria type I (PHI) are at risk to systemically deposit calcium-oxalate crystals. This systemic oxalosis may occur even at early stages of chronic kidney failure (CKD) but is difficult to detect with non-invasive imaging procedures.

Methods

We tested if magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is sensitive to detect oxalate deposition in bone. A 3 Tesla MRI of the left knee/tibial metaphysis was performed in 46 patients with PHI and in 12 healthy controls. In addition to the investigator’s interpretation, signal intensities (SI) within a region of interest (ROI, transverse images below the level of the physis in the proximal tibial metaphysis) were measured pixelwise, and statistical parameters of their distribution were calculated. In addition, 52 parameters of texture analysis were evaluated. Plasma oxalate and CKD status were correlated to MRI findings. MRI was then implemented in routine practice.

Results

Independent interpretation by investigators was consistent in most cases and clearly differentiated patients from controls. Statistically significant differences were seen between patients and controls (p < 0.05). No correlation/relation between the MRI parameters and CKD stages or Pox levels was found. However, MR imaging of oxalate osteopathy revealed changes attributed to clinical status which differed clearly to that in secondary hyperparathyroidism.

Conclusions

MRI is able to visually detect (early) oxalate osteopathy in PHI. It can be used for its monitoring and is distinguished from renal osteodystrophy. In the future, machine learning algorithms may aid in the objective assessment of oxalate deposition in bone.

A higher resolution version of the Graphical abstract is available as Supplementary information.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All anonymized clinical data are available in the supplemental files. All anonymized patient data are included in the German Hyperoxaluria PH Registry (www.ph-registry.net).

Change history

11 January 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-022-05868-9

References

Bobrowski AE, Langman CB (2006) Hyperoxaluria and systemic oxalosis: current therapy and future directions. Expert Opin Pharmacother 7:1887–1896. https://doi.org/10.1517/14656566.7.14.1887

Hoppe B, Beck BB, Milliner DS (2009) The primary hyperoxalurias. Kidney Int 75:1264–1271. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2009.32

Hoppe B (2012) An update on primary hyperoxaluria. Nat Rev Nephrol 8:467–475. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2012.113

Pey AL, Albert A, Salido E (2013) Protein homeostasis defects of alanine-glyoxylate aminotransferase: new therapeutic strategies in primary hyperoxaluria type I. Biomed Res Int 2013:687658. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/687658

van Woerden CS, Groothoff JW, Wanders RJA, Davin JC, Wijburg FA (2003) Primary hyperoxaluria type 1 in The Netherlands: prevalence and outcome. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18:273–279. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/18.2.273

Hopp K, Cogal AG, Bergstralh EJ, Seide BM, Olson JB, Meek AM, Lieske JC, Milliner DM, Harris PC (2015) Phenotype-Genotype correlations and estimated carrier frequencies of primary hyperoxaluria. J Am Soc Nephrol 26:2559–2570. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2014070698

Danpure CJ (1968) Peroxisomal alanine:glyoxylate aminotransferase and prenatal diagnosis of primary hyperoxaluria type 1. Lancet 2:1168. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(86)90584-2

Cochat P, Liutkus A, Fargue S, Basmaison O, Ranchin B, Rolland MO (2006) Primary hyperoxaluria type 1: still challenging! Pediatr Nephrol 21:1075–1081. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-006-0124-4

Knauf F, Asplin JR, Granja I, Schmidt IM, Moeckel GW, David RJ, Flavell RA, Aronson PS (2013) NALP3-mediated inflammation is a principal cause of progressive renal failure in oxalate nephropathy. Kidney Int 84:895–901. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2013.207

Hoppe B, Kemper MJ, Bokenkamp A, Langman CB (1998) Plasma calcium-oxalate saturation in children with renal insufficiency and in children with primary hyperoxaluria. Kidney Int 54:921–925. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00066.x

Behnke B, Kemper MJ, Kruse HP, Müller-Wiefel DE (2001) Bone mineral density in children with primary hyperoxaluria type I. Nephrol Dial Transplant 16:2236–2239. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/16.11.2236

Cochat P, Basmaison O (2000) Current approaches to the management of primary hyperoxaluria. Arch Dis Child 82:470–473. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.82.6.470

Bacchetta J, Boivin G, Cochat P (2016) Bone impairment in primary hyperoxaluria: a review. Pediatr Nephrol 31:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-015-3048-z

Schnitzler CM, Kok JA, Jacobs DW, Thomson PD, Milne FJ, Mesquita JM, King PC, Fabian VA (1991) Skeletal manifestations of primary oxalosis. Pediatr Nephrol 5:193–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01095951

Lorenzo V, Alvarez A, Torres A, Torregrosa V, Hernández D, Salido E (2006) Presentation and role of transplantation in adult patients with type 1 primary hyperoxaluria and the I244T AGXT mutation: Single-center experience. Kidney Int 70:1115–1119. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ki.5001758

Hernandez JD, Wesseling K, Pereira R, Gales B, Harrison R, Salusky IB (2008) Technical approach to iliac crest biopsy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3(Suppl 3):S164-169. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.00460107

Garrelfs SF, Frishberg Y, Hulton SA, Koren MJ, O'Riordan WD, Cochat P, Deschênes G, Shasha-Lavsky H, Saland JM, Van't Hoff WG, Fuster DG, Magen D, Moochhala SH, Schalk G, Simkova E, Groothoff JW, Sas DJ, Meliambro KA, Lu J, Sweetser MT, Garg PP, Vaishnaw AK, Gansner JM, McGregor TL, Lieske JC; ILLUMINATE-A Collaborators (2021) Lumasiran, an RNAi therapeutic for primary hyperoxaluria type 1. N Engl J Med 384:1216–1226. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2021712

Hoppe B, Koch A, Cochat P, Garrelfs SF, Baum MA, Groothoff JW, Lipkin G, Coenen M, Schalk G, Amrite A, McDougall D, Barrios K, Langman CB (2022) Safety, pharmacodynamics, and exposure-response modeling results from a first-in-human phase 1 study of nedosiran (PHYOX1) in primary hyperoxaluria. Kidney Int 101:626–634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2021.08.015

Danpure CJ (2004) Molecular aetiology of primary hyperoxaluria type 1. Nephron Exp Nephrol 98:e39-44. https://doi.org/10.1159/000080254

Williams EL, Acquaviva C, Amoroso A, Chevalier F, Coulter-Mackie M, Monico CG, Giachino D, Owen T, Robbiano A, Salido E, Waterham H, Rumsby G (2009) Primary hyperoxaluria type 1: update and additional mutation analysis of the AGXT gene. Hum Mutat 30:910–917. https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.21021

Schwartz GJ, Muñoz A, Schneider MF, Mak RH, Kaskel F, Warady BA, Furth SL (2009) New equations to estimate GFR in children with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 20:629–637. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2008030287

Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) (2009) A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150:604–612. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006

KDIGO (2013) KDIGO 2012 Clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 3:5–14

Hoppe B, Kemper MJ, Bökenkamp A, Portale AA, Cohn RA, Langman CB (1999) Plasma calcium oxalate supersaturation in children with primary hyperoxaluria and end-stage renal failure. Kidney Int 56:268–274. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00546.x

Vallières M, Freeman CR, Skamene SR, El Naqa I (2015) A radiomics model from joint FDG-PET and MRI texture features for the prediction of lung metastases in soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities. Phys Med Biol 60:5471–5496. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/60/14/5471

Strauss SB, Waltuch T, Bivin W, Kaskel F, Levin TL (2017) Primary hyperoxaluria: spectrum of clinical imaging findings. Pediatr Radiol 47:96–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-016-3723-7

Wiggelinkhuizen J, Fisher RM (1982) Oxalosis of bone. Pediatr Radiol 12:307–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00973200

Brancaccio D, Poggi A, Ciccarelli C, Bellini F, Galmozzi C, Poletti I, Maggiore (1981) Bone changes in end-stage oxalosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 136:935–939. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.136.5.935

El Hage S, Ghanem I, Baradhi A, Mourani C, Mallat S, Dagher F, Kharrat K (2008) Skeletal features of primary hyperoxaluria type 1, revisited. J Child Orthop 2:205–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11832-008-0082-4

Devresse A, Lhommel R, Godefroid N, Goffin E, Kanaan N (2022) 18-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission computed tomography for systemic oxalosis in primary hyperoxaluria type 1. Am J Transplant 22:1001–1002. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.16887

Tonnelet D, Benali K, Rasmussen C, Goulenok T, Piekarski E (2020) Diffuse hypermetabolic bone marrow infiltration in severe primary hyperoxaluria on FDG PET. Clin Nucl Med 45:e296–e298. https://doi.org/10.1097/RLU.0000000000003047

Kwon HW, Kim JP, Lee HJ, Paeng JC, Lee JS, Cheon GJ, Lee DS, Chung JK, Kang KW (2016) Radiation dose from whole-body F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography: nationwide survey in Korea. J Korean Med Sci 31(Suppl 1):S69-74. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2016.31.S1.S69

Lagies R, Udink Ten Cate FEA, Feldkötter M, Beck BB, Sreeram N, Hoppe B, Herberg U (2019) Subclinical myocardial disease in patients with primary hyperoxaluria and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: a two-dimensional speckle-tracking imaging study. Pediatr Nephrol 34:2591–2600. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-019-04330-7

Van Der Hoeven SM, Van Woerden CS, Groothoff JW (2012) Primary hyperoxaluria Type 1, a too often missed diagnosis and potentially treatable cause of end-stage renal disease in adults: results of the Dutch cohort. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27:3855–3862. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfs320

Acknowledgements

We thank Mrs. Brigitte Baer and Dr. Lodovica Borghese for their assistance in screening laboratory data.

Funding

This project has received funding in part from the German Research Foundation (DFG; Grant within the SFB/TRR 57 to BH). CMH is funded by a Juan de la Cierva postdoctoral grant both from the Spanish Ministry of Science (Reference FJC2018-036199-I) and the German primary hyperoxaluria self support group (PH-Selbsthilfe).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

BH has been an employee, and CMH is a consultant of Dicerna Pharmaceuticals, a Novo Nordisk subsidiary, Lexington, USA.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: The legend of Figure 4 has been corrected.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Merz, LM., Born, M., Kukuk, G. et al. Three Tesla magnetic resonance imaging detects oxalate osteopathy in patients with primary hyperoxaluria type I. Pediatr Nephrol 38, 2083–2092 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-022-05836-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-022-05836-3