Abstract

Background

Several procedures have been proposed to reduce the rates of recurrence in patients with right-sided colon cancer. Different procedures for a radical right colectomy (RRC), including extended D3 lymphadenectomy, complete mesocolic excision and central vascular ligation have been associated with survival benefits by some authors, but results are inconsistent. The aim of this study was to assess the variability in definition and reporting of RRC, which might be responsible for significant differences in outcome evaluation.

Methods

PRISMA-compliant systematic literature review to identify the definitions of RRC. Primary aims were to identify surgical steps and different nomenclature for RRC. Secondary aims were description of heterogeneity and overlap among different RRC techniques.

Results

Ninety-nine articles satisfied inclusion criteria. Eight surgical steps were identified and recorded as specific to RRC: Central arterial ligation was described in 100% of the included studies; preservation of mesocolic integrity in 73% and dissection along the SMV plane in 67%. Other surgical steps were inconstantly reported. Six differently named techniques for RRC have been identified. There were 35 definitions for the 6 techniques and 40% of these were used to identify more than one technique.

Conclusions

The only universally adopted surgical step for RRC is central arterial ligation. There is great heterogeneity and consistent overlap among definitions of all RRC techniques.

This is likely to jeopardise the interpretation of the outcomes of studies on the topic. Consistent use of definitions and reporting of procedures are needed to obtain reliable conclusions in future trials. PROSPERO CRD42021241650.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Stage at diagnosis represents the most important predictor of survival in patients with colonic cancer [1, 2]. Tumours located in the proximal colon have lower survival rates, but this association may be confined to distant-stage diagnoses [3]. Among other factors, the extent of lymphadenectomy and resection have been advocated as determinants of recurrence.

Lymphatic stations to be removed in patients with right-sided colon cancer are still a matter of discussion [4]. Discrepancies exist in terms of extent of lymphadenectomy in available guidelines, with Asian guidelines advocating extended lymph node removal (D3) on a routine basis in T3/T4 and selected T2 cancers, whereas this is still debated in other countries [5]. D3 lymphadenectomy involves removal of the lymphoadipose tissue covering the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) (also known as surgical trunk of Gillot) and the gastrocolic trunk of Henle (GCTH) [6, 7]. The authors have suggested a survival benefit in stage II and III colon cancer with D3 compared with conventional (D2) lymphadenectomy [8]. However, this is not consistently observed in the literature.

The technique proposed by Hohenberger in 2009, namely the Complete Mesocolic Excision (CME), introduced a further concept, the importance of preserving mesocolic integrity and achieving its complete removal [9]. The technique required sharp dissection between the right mesocolon and the retroperitoneum, taking as landmark the embryological plane resulting by the fusion fascia of Toldt and the fusion fascia of Fredet, followed by central vascular ligation (CVL) of ileocolic vessels, right colic vessels, and right branch of middle colic vessels [9]. Implementing CME, the authors were able to halve the local 5-year recurrence rate at their institution (6.5% vs 3.6% before and after CME use) [9].

Following the description of CME by Hohenberger, which can be combined with D3 lymphadenectomy, the role of extensive or more radical resection for colon cancer has generated growing interest, resulting in several studies being published with the aim of optimizing right colon resections for cancer. However, the definition of the procedures used for Radical Right Colectomy (RRC) has not been consistently used. Studies have been describing the technique used with different names, e.g. “CME”, “CVL”, “D3” and their variants. Until this question is solved, reliability of results presented and especially their comparison and generalizability remain poor [10,11,12]. This is relevant as any additional manoeuvre can produce unnecessary complications.

The aim of this study was to conduct a systematic review of all definitions for RRC, in order to identify potential discrepancies and areas for improvement.

Methods

Data sources and search

This is a systematic literature review performed in accordance with the current Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA 2020) guidelines for systematic reviews (Table S1) [13].

This systematic review was registered on PROSPERO under the protocol number CRD42021241650.

Searches were conducted for all English language full-text articles published until 31st October 2021. The following database sources were searched: PubMed (MEDLINE), Scopus, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Web of Science.

The following term combination was used in each database: ((((complete mesocolon excision) OR (CME)) OR (D3)) OR (central vascular ligation)) AND (right hemicolectomy), ((((CME) OR (central vascular ligation)) OR (complete mesocolon excision) OR (D3)) AND (colon cancer)) NOT (right hemicolectomy), (((((CME) OR (central vascular ligation)) OR (complete mesocolon excision) OR (D3)) AND (colonic cancer)) NOT (right hemicolectomy)) NOT (colon cancer). These terms were created by one of the authors, with previous experience in systematic reviews (G.P.).

Furthermore, the references list of each selected article was analysed to identify additional relevant studies.

Records were screened for relevance based on their title and abstract, and successively, the full text of the remaining articles was analysed.

Inclusion criteria and outcome definition

The type of studies eligible for inclusion were original articles (retrospective, prospective, randomised controlled trials [RCT]), systematic reviews and meta-analysis. The presence of a clear definition of the surgical technique in the methods section was considered a fundamental additional inclusion criterion.

Three authors (D.V., A.M.G. and L.S.) independently screened each record from full-text articles for eligibility and extracted the data, including quality analysis. Disagreement was resolved by discussion and consensus; if no agreement was reached, a fourth author was consulted (B.S.).

The primary aims were the identification of (a) the surgical steps for RRC, (b) the different nomenclatures adopted and (c) the number of reports and prevalence of each RRC step for a given technique. A surgical step for RRC was defined as a surgical manoeuvre mentioned by a given article as being exclusive to RRC as opposed to standard right colectomy. A nomenclature was defined as a particular name given to describe an RRC technique.

Secondary aims included the identification of definitions for each RRC nomenclature (each made up of a combination of the RRC steps previously identified) and the heterogeneity and overlaps in these definitions.

Heterogeneity was defined as the absolute number and percentage of different definitions for a given RRC nomenclature, which will be reported in a table. Overlap was defined as the percentage of definitions that were used to describe two or more different RRC nomenclatures.

A sub-analysis identified RRC steps in Western (including Australia, Russia and Turkey) vs Asian countries and in different time periods (2009–2015 vs 2016–2021) in an effort to detect geographical or temporal peculiarities/tendencies.

Data extraction and quality assessment (Fig. S1)

Each article was carefully read and analysed independently by two authors (B.S. and L.S.) in an effort to identify surgical steps that authors attributed specifically to RRC as opposed to a minimal/standard right colectomy.

Study quality was assessed using Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) for non-RCTs and the modified Jadad scale score for RCTs.

NOS is an assessment tool used to measure the quality of non-randomized studies included in systematic reviews [14]. Each article was assessed for 9 parameters, each awarding up to one point, with a maximum total score of 9 points. Modified Jadad scale score is used to assess the quality of RCT by evaluating three parameters each awarding one point with three point awarded for high-quality RCT [15].

Data synthesis (Fig. S1)

The techniques described in each article were listed based on the presence or absence of each of the steps previously identified. These data were grouped in an excel sheet.

Furthermore, the definition of each technique given by the original author was recorded to reveal overlapping of definitions and evaluate heterogeneity.

Descriptive statistics were produced from the dataset: categorical data were merged and are reported as numbers and/or percentages. There was no comparative statistical analysis.

Results

Systematic search

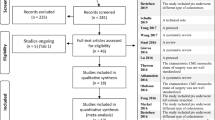

The systematic search process is summarised in Fig. 1. The initial database search identified 2602 articles. After initial screening and exclusion of duplications and after full-text reading of the remaining articles, 99 eligible articles were included in the qualitative review.

Quality assessment

Table 1 summarizes year, journal, design and country of publication for each study as well as NOS or Jadad scale score [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113]. All studies were published between 2009 and 2021 and > 50% from 2018 onwards. The most common study type was retrospective (54%), while only 3% of the studies included were RCTs. Average NOS score was 7.8 and average modified Jadad scale score was 6.7.

Primary aim: RRC surgical steps

Eight surgical steps were identified and recorded as specific for RRC as opposed to standard right colectomy:

-

(1)

Central arterial ligation (at the root from the superior mesenteric artery (SMA)).

-

(2)

Preservation of mesocolic integrity.

-

(3)

Dissection along the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) plane.

-

(4)

Dissection along the left border of the SMA.

-

(5)

Dissection of the gastrocolic trunk of Henle (GCTH).

-

(6)

Sub-pyloric lymph-nodes dissection.

-

(7)

Complete Kocher’s manoeuvre.

-

(8)

Omentectomy.

Central arterial ligation was described in 100% of the included studies; preservation of mesocolic integrity in 73%; dissection along the SMV plane in 67%; dissection along the left border of the SMA in 11%; dissection of the GCTH in 45%; sub-pyloric lymph-nodes dissection in 18%; a complete Kocher’s manoeuvre in 11% and an omentectomy in 39% of studies.

Primary aim: RRC nomenclature

Analysis of nomenclature identified six RRC techniques: complete mesocolic excision (CME), complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation (CME + CVL), central vascular ligation (CVL), modified complete mesocolic excision (mCME), D3 lymphadenectomy (D3) and complete mesocolic excision with D3 lymphadenectomy (CME + D3).

Primary aim: number of reports and prevalence of each surgical step for a given technique

-

(1)

CME (n of studies = 48)

All CMEs studies reported central arterial ligation but not all the papers clearly reported preservation of mesocolic integrity (83.3%) and SMV dissection (66.7%). GCTH dissection was associated in 35.4%, sub-pyloric lymph-nodes dissection in 20.8%, omentectomy in 41.7% and a full Kocher’s manoeuvre in 12.5%.

-

(2)

CME + CVL (n = 22)

CME + CVL descriptions included preservation of mesocolic integrity in 83.3%, SMV dissection in 54.5% and SMA dissection in 9.1%. GCTH dissection was described in 40.9%, sub-pyloric nodes retrieval in 18.2%, omentectomy in 45.5% and a full Kocher’s manoeuvre in 13.6%.

-

(3)

CVL (n = 1)

CVL only: this paper described central arterial ligation only.

-

(4)

Modified CME (mCME, n = 5)

mCME is a “modified technique” of CME that included preservation of mesocolic integrity, reported in 80% and SMV dissection in 60%. GCTH dissection was reported in 60% of the papers, sub-pyloric nodes retrieval in 20% and omentectomy in 40%. Dissection along the SMA or a full Kocher’s manoeuvre was not reported.

-

(5)

D3 (n = 18)

D3 studies included preservation of mesocolic integrity in 33.30%, dissection of the SMV in 83.3% and of the SMA in 38% of reports. Dissection of GCTH and sub-pyloric nodes were reported in 66.6% and 16.7%, respectively; omentectomy and a full Kocher’s manoeuvre in 22.2% and in 5.5%, respectively.

-

(6)

CME + D3 (n = 5)

CME + D3 studies included mesocolic preservation in 100%, dissection along the SMV in 80%, along the SMA in 0%, of the GCTH in 80%, of the sub-pyloric nodes in 0%, a full Kocher manoeuvre in 0% and omentectomy in 40%.

Results of systematic analysis of surgical techniques are summarised in Table 2.

Secondary aim: heterogeneity in definitions

Thirty-five different definitions of RRC were identified (Table 3). The definitions used in each study are reported in Table S2 [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113]. Among the forty-eight articles regarding CME, there were twenty-two different descriptions of the operation. The most common definitions (recurring in 16.67% of studies) were central arterial ligation and preservation of mesocolic integrity. CME + CVL featured fourteen different definitions in twenty-two studies, the most common of which (35.71%) included only central arterial ligation and conservation of mesocolic integrity. The modified version of CME (mCME) was defined in four different ways. D3 was described with eleven different techniques: the most common technique (22.22%) included CVL, mesocolic preservation, SMV dissection, gastrocolic and pyloric nodes dissections and omentectomy. D3 + CME featured five descriptions, in 40% of cases including CVL, mesocolic preservation, SMV, gastrocolic and pyloric nodes dissection.

Secondary aim: overlap in definitions

Forty percent of the definitions were used to identify more than one RRC technique. Regarding CME, 36.36% of definitions were unique, while the rest overlapped with definitions used for CME + CVL (40.90%), D3 (22.72%), mCME (13.64%), and D3 + CME (13.64%). For what concerns CME + CVL, 28.57% of definitions were unique, while the rest overlapped with CME (64.29%), D3 (14.29%), mCME (14.29%) or D3 + CME (21.42%). For mCME, 75% of definitions overlapped with CME, 50% with CME + CVL, 50% with D3 and 25% with D3 + CME. D3 + CME had no unique definition, with 75% overlap with CME, 75% with CME + CVL, 25% with mCME and 50% with D3. D3 had 54.54% of unique definitions, while others overlapped with CME (45.45), CME + CVL (27.27%), mCME (18.18%), D2 + CME (18.18%).

East vs West

All six RRC steps were used by both Easter and Western studies. Of note, omentectomy was more prevalent in Eastern studies (48% vs 30.6%) as was GCTH dissection (54% vs 36,7%), while sub-pyloric lymph-node dissection was more common in the West (14% vs 22,4%), and dissection along the left border of the SMA was almost three times more common in the west (6 vs 16,3%) (Fig. S2).

RRC over time

All six RRC steps were used in both periods. Of note, omentectomy (32,3% vs 42,6%), dissection along the SMV (58,1% vs 70,6%) and dissection of GCTH (35,5% vs 50,0%) were more prevalent in more recent time (Fig. S3).

Discussion

The current systematic review identified significant variability in the reporting and definitions of RRC, despite the existence of standardised, systematic descriptions that have been produced over years. Up to 35 different combinations of the key components of a RRC were observed, with several studies inappropriately claiming to perform a given procedure according to the descriptions provided by the authors. Such variability raises several concerns, as it is difficult to address the actual benefits of extensive approaches when no agreed terminology and procedures are being adopted.

Since the detailed description of D3 lymphadenectomy advocated by Asian guidelines [114] and the report on CME with CVL by Hohenberger et al. [9] to perform a RRC, a vast myriad of articles with a combination of definitions of RRC have been published.

The lack of uniformity undermines the proper evaluation of the clear benefits of any technique over the others. It is interesting to note that the CME description by Hohenberger [9] clearly differs from any “standard” right hemicolectomy for right colon cancer, but some of the proposed techniques do not differ from a proper right colectomy for cancer. Even if some authors have suggested some benefits of extended lymphadenectomy [115], most agree that there is need for more prospective or randomised studies to identify this as necessary for RRC [116]. The discrepancies in available definitions used in the published studies make it difficult to draw conclusions.

This systematic review offers several contributions to the understanding of RRC. It identifies the fundamental surgical steps reported by every single study. Commonly used definitions of these steps can be found in Table 4. Some of these surgical steps are adopted quite uniformly by all the authors, while others seem not to be considered fundamental.

The main surgical steps commonly shared by the authors are two, central arterial ligation and preservation of the mesocolic integrity. Central arterial ligation ensures harvesting of all nodes along the colon’s feeding vessels (ileocolic vessels and right branch of the middle colic vessels in RRC).

It allows a significantly higher number of nodes to be excised compared to so-called low-tie of the organ’s vessels. This technique indeed may provide rationale for superior oncological results (in terms of both local and distal control) [9] but certainly it is not a novel concept; high-tie of vascular structures being one of the pillars of oncologic surgery. The rationale to remove more lymph nodes is also suggested by reports on lymph node ratio (number of positive nodes divided by the total number of harvested nodes) that can be more prognostically relevant than the number of positive nodes per se [117]. Preservation of mesocolic integrity is predominantly mentioned in studies focussing on CME and it can be properly regarded as a “novel” manoeuvre; it follows a well-known anatomical dissection plane and encompasses the removal of all the lymphoadipose tissue lateral to the SMV. The embryologic fasciae that need to be respected during RRC with CME would be the fusion fascia of Toldt and the fusion fascia of Fredet [118,119,120].

Whether the integrity of the mesocolic fascia does represent a necessity to prevent local recurrence is far from being clarified. The proposers of CME should be credited for having raised attention towards the importance of a truly radical approach to right colon cancers [9]

A retrospective study of surgical specimens reported longer survival for those patients with stage III colon cancer whose colon was excised with intact mesocolon, compared with patients who had received less than optimal surgery. The surgical technique is well defined and requires the surgeon (1) to remain within the mesocolic plane, (2) to perform central ligation of the tumour-feeding artery, and (3) to remove an appropriate length of large bowel on either side of the tumour [100]. A medial to lateral approach to dissection has been advocated with laparoscopy and a lateral to medial one in open surgery, but the direction of dissection was independent from extent of resection and never reported as specific to RRC.

According to Hohenberger et al. [9], the lymphoadipose tissue covering the SMV and the head of the pancreas should be removed in the event of potentially affected nodes at preoperative CT scan, or if these are detected intraoperatively at these sites. The removal of the lymphoadipose tissue along both lateral and medial sides of SMV and the GCTH defines a D3 lymphadenectomy [8, 121, 122].

For what concerns the other surgical steps variably associated to RRC, the consensus drops significantly, and they are reported by a minority of authors.

The dissection along the SMV between the ileocolic vein and the GCTH (Gillot’s fat pad) [123] is based on data suggesting that 3% of right colon cancer metastasise to central lymph nodes, located anteriorly to the SMV [19, 117, 128,129,130,131]. This may be important in the staging process (as up to 0.2–2% of patients harbour skip metastases in central nodes) and might probably ameliorate prognosis [117, 128, 129]. The SMV plane of dissection is an excellent surgical plane for dissection. Nevertheless, it can be considered dangerous due to the importance of the structure and because of the thin wall of the vein [132,133,134].

Authors reporting on the more extensive D3 lymphadenectomy most frequently mention dissection of the SMA. This procedure may result in autonomic dysfunction, due to consensual resection of nerve plexuses lying anterior to the SMA. Symptoms may include severe refractory diarrhoea [94, 95].

Dissection of the GCTH requires the removal of lymphoadipose tissue covering the head of the pancreas and is usually employed by authors of D3 or in case of tumours of the hepatic flexure or proximal transverse colon. No study to date has specifically focussed on the advantages of this surgical step alone.

Dissection of sub-pyloric lymph nodes, complete Kocher manoeuvre and omentectomy are generally not considered integral part of RRC if not in a limited number of reports. Dissection of station six nodes could be theoretically useful in cancers of the hepatic flexure and proximal transverse colon [135]. As said, no benefit has been demonstrated and there is no consensus to its routine application. A complete Kocher manoeuvre allows dissection of retro-duodenopancreatic nodes, but no rationale exists for their removal in colon cancer. The utility of omentectomy in colonic surgery has not been thoroughly investigated to date.

Different authors with variable combinations of the main surgical steps, resulting in a great heterogeneity of definitions, have defined individual surgical techniques. In this systematic review, 36.36% of CME definitions were unique, while the rest overlapped with definitions used for CME + CVL (40.90%), D3 (22.72%), mCME (13.64%) and D3 + CME (13.64%).

Obviously, this variability in definition makes aggregation of results from these studies incorrect from a methodological point of view, such that meta-analyses would be of questionable scientific value. In fact, the current “CME” literature includes different surgical operations, which are mistakenly given the same name.

Of course, this introduces a further element of confusion in interpretation of the literature, making comparison among different RRC techniques virtually impossible and the twelve ongoing randomized trials possibly not completely confrontable. Of note, there have been proposals for standardised assessment and reporting of CME and D3 lymphadenectomy in RRC; a consistent utilisation of such approaches could ease the interpretation of prospective studies, allowing to objectively addressing whether extended approaches confer any survival benefit [136, 137].

After more than 10 years of debate, it is apparent that a clarification on surgical technique has been long overdue: a globally agreed consensus on the precise surgical steps to be performed for each given procedure (herein defined RRC) is necessary and expectedly awaited.

Conclusions

Central arterial ligation is unanimously considered indispensable to perform RRC for right colon cancer. Other surgical steps are more debated; preservation of mesocolic integrity has clearly a central role in CME and dissection along the SMV in D3. There is great heterogeneity and consistent overlap among definitions of all RRC techniques. Confusion in the definition of a RRC might jeopardise the reliability of available results, limiting the generalizability, and making comparisons difficult. Consensus definitions are warranted to usher progress in right colon cancer surgery.

Change history

04 November 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-022-09747-0

References

Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A (2015) Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 65:87–108

Amelio I, Bertolo R, Bove P, Buonomo OC, Candi E, Chiocchi M, Cipriani C, Di Daniele N, Ganini C, Juhl H, Mauriello A, Marani C, Marshall J, Montanaro M, Palmieri G, Piacentini M, Sica G, Tesauro M, Rovella V, Tisone G, Shi Y, Wang Y, Melino G (2020) Liquid biopsies and cancer omics. Cell Death Discov 6(1):131. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-020-00373-0

Characteristics of Early-Onset vs Late-Onset Colorectal Cancer: A Review. REACCT Collaborative. JAMA Surg. 2021. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2021.2380

Vogel JD, Felder SI, Bhama AR, Hawkins AT, Langenfeld SJ, Shaffer VO, Thorsen AJ, Weiser MR, Chang GJ, Lightner AL, Feingold DL, Paquette IM (2022) The American society of colon and rectal surgeons clinical practice guidelines for the management of colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 65(2):148–177. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000002323

Hashiguchi Y, Muro K, Saito Y, Ito Y, Ajioka Y, Hamaguchi T, Hasegawa K, Hotta K, Ishida H, Ishiguro M, Ishihara S, Kanemitsu Y, Kinugasa Y, Murofushi K, Nakajima TE, Oka S, Tanaka T, Taniguchi H, Tsuji A, Uehara K, Ueno H, Yamanaka T, Yamazaki K, Yoshida M, Yoshino T, Itabashi M, Sakamaki K, Sano K, Shimada Y, Tanaka S, Uetake H, Yamaguchi S, Yamaguchi N, Kobayashi H, Matsuda K, Kotake K, Sugihara K (2020) Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol 1:1–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-019-01485-z

Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (2019) Japanese Classification of colorectal, appendiceal, and anal carcinoma: the 3d English edition [Secondary Publication]. J Anus Rectum Colon 3(4):175–195. https://doi.org/10.23922/jarc.2019-018

Mike M, Kano N (2013) Reappraisal of the vascular anatomy of the colon and consequences for the definition of surgical resection. Dig Surg 30(4–6):383–392. https://doi.org/10.1159/000343156

Numata M, Sawazaki S, Aoyama T, Tamagawa H, Sato T, Saeki H, Saigusa Y, Taguri M, Mushiake H, Oshima T, Yukawa N, Shiozawa M, Rino Y, Masuda M (2019) D3 lymph node dissection reduces recurrence after primary resection for elderly patients with colon cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis 34(4):621–628. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-018-03233-7 (Epub 2019 Jan 18 PMID: 30659360)

Hohenberger W, Weber K, Matzel K, Papadopoulos T, Merkel S (2009) Standardized surgery for colonic cancer: complete mesocolic excision and central ligation–technical notes and outcome. Colorectal Dis 11(4):354–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01735.x

Ferri V, Vicente E, Quijano Y, Duran H, Diaz E, Fabra I, Malave L, Agresott R, Isernia R, Cardinal-Fernandez P, Ruiz P, Nola V, de Nobili G, Ielpo B, Caruso R (2021) Right-side colectomy with complete mesocolic excision vs conventional right-side colectomy in the treatment of colon cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis 36(9):1885–1904. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-021-03951-5

Mazzarella G, Muttillo EM, Picardi B, Rossi S, Muttillo IA (2021) Complete mesocolic excision and D3 lymphadenectomy with central vascular ligation in right-sided colon cancer: a systematic review of postoperative outcomes, tumor recurrence and overall survival. Surg Endosc 35(9):4945–4955. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-021-08529-4

Anania G, Davies RJ, Bagolini F, Vettoretto N, Randolph J, Cirocchi R, Donini A (2021) Right hemicolectomy with complete mesocolic excision is safe, leads to an increased lymph node yield and to increased survival: results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol 25(10):1099–1113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-021-02471-2

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of non-randomised studies in meta-analyses. https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinicalepidemiology/oxford.asp

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D et al (1996) Assessing the quality of reports of randomizedclinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 17:1–12

Alharbi RA, Hakami R, Alkhayal KA, Al-Obeed OA, Traiki TA, Zubaidi A et al (2020) Long-term outcomes after complete mesocolic excision for colon cancer at a tertiary care center in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med 40(3):207–211. https://doi.org/10.5144/0256-4947.2020.207

Alhassan N, Yang M, Wong-Chong N, Liberman AS, Charlebois P, Stein B et al (2019) Comparison between conventional colectomy and complete mesocolic excision for colon cancer: a systematic review and pooled analysis: a review of CME versus conventional colectomies. Surg Endosc 33(1):8–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6419-2

Bae SU, Yang SY, Min BS (2019) Totally robotic modified complete mesocolic excision and central vascular ligation for right-sided colon cancer: technical feasibility and mid-term oncologic outcomes. Int J Colorectal Dis 34:471–479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-018-3208-2

Balciscueta Z, Balciscueta I, Uribe N, Pellino G, Frasson M, García-Granero E, García-Granero Á (2021) D3-lymphadenectomy enhances oncological clearance in patients with right colon cancer. Results of a meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2021.02.020

Benz S, Tannapfel A, Tam Y et al (2019) Proposal of a new classification system for complete mesocolic excison in right-sided colon cancer. Tech Coloproctol 23:251–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-019-01949-4

Bernhoff R, Sjövall A, Buchli C, Granath F, Holm T, Martling A (2018) Complete mesocolic excision in right-sided colon cancer does not increase severe short-term postoperative adverse events. Colorectal Dis 20(5):383–389. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.13950

Bertelsen CA, Larsen HM, Neuenschwander AU, Laurberg S, Kristensen B, Emmertsen KJ (2018) Long-term functional outcome after right-sided complete mesocolic excision compared with conventional colon cancer surgery: a population-based questionnaire study. Dis Colon Rectum 61(9):1063–1072. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000001154

Ceccarelli G, Costa G, Ferraro V, De Rosa M, Rondelli F, Bugiantella W (2021) Robotic or three-dimensional (3D) laparoscopy for right colectomy with complete mesocolic excision (CME) and intracorporeal anastomosis? A propensity score-matching study comparison. Surg Endosc 35(5):2039–2048. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-07600-w

Chaouch MA, Dougaz MW, Bouasker I et al (2019) Laparoscopic versus open complete mesocolon excision in right colon cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg 43:3179–3190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-019-05134-4

Dai W, Zhang J, Xiong W, Xu J, Cai S, Tan M, He Y, Song W, Yuan Y (2018) Laparoscopic right hemicolectomy oriented by superior mesenteric artery for right colon cancer: efficacy evaluation with a match-controlled analysis. Cancer Manag Res 30(10):5157–5170. https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S178148

Daniels M, Merkel S, Agaimy A, Hohenberger W (2015) Treatment of perforated colon carcinomas-outcomes of radical surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis 30(11):1505–1513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-015-2336-1

Du S, Zhang B, Liu Y et al (2018) A novel and safe approach: middle cranial approach for laparoscopic right hemicolon cancer surgery with complete mesocolic excision. Surg Endosc 32:2567–2574. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-017-5982-2

Ehrlich A, Kairaluoma M, Böhm J, Vasala K, Kautiainen H, Kellokumpu I (2016) Laparoscopic wide mesocolic excision and central vascular ligation for carcinoma of the colon. Scand J Surg 105(4):228–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/1457496915613646

Elias AW, Merchea A, Moncrief S et al (2020) Recurrence and long-term survival following segmental colectomy for right-sided colon cancer in 813 patients: a single-institution study. J Gastrointest Surg 24:1648–1654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-019-04271-4

Schulte am Esch J, Iosivan SI, Steinfurth F et al (2019) A standardized suprapubic bottom-to-up approach in robotic right colectomy: technical and oncological advances for complete mesocolic excision. BMC Surg 19:72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-019-0544-2

Feng B, Sun J, Ling TL, Lu AG, Wang ML, Chen XY, Ma JJ, Li JW, Zang L, Han DP, Zheng MH (2012) Laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision (CME) with medial access for right-hemi colon cancer: feasibility and technical strategies. Surg Endosc 26(12):3669–3675. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-012-2435-9

Feng B, Ling TL, Lu AG, Wang ML, Ma JJ, Li JW, Zang L, Sun J, Zheng MH (2014) Completely medial versus hybrid medial approach for laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision in right hemicolon cancer. Surg Endosc 28(2):477–483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-013-3225-8 (Epub 2013 Oct 11)

Furnes B, Storli KE, Forsmo HM, Karliczek A, Eide GE, Pfeffer F (2019) Risk factors for complications following introduction of radical surgery for colon cancer: a consecutive patient series. Scand J Surg 108(2):144–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/1457496918798208

Galizia G, Lieto E, De Vita F et al (2014) Is complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation safe and effective in the surgical treatment of right-sided colon cancers? A prospective study. Int J Colorectal Dis 29:89–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-013-1766-x

Gao Z, Wang C, Cui Y, Shen Z, Jiang K, Shen D, Wang Y, Zhan S, Guo P, Yang X, Liu F, Shen K, Liang B, Yin M, Xie Q, Wang Y, Wang S, Ye Y (2020) Efficacy and safety of complete mesocolic excision in patients with colon cancer: three-year results from a prospective, nonrandomized, double-blind. Controlled Trial Ann Surg 271(3):519–526. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003012

Gaupset R, Nesgaard JM, Kazaryan AM, Stimec BV, Edwin B, Ignjatovic D (2018) Introducing anatomically correct CT-guided laparoscopic right colectomy with D3 anterior posterior extended mesenterectomy: initial experience and technical pitfalls. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 28(10):1174–1182. https://doi.org/10.1089/lap.2018.0059

Gouvas N, Pechlivanides G, Zervakis N, Kafousi M, Xynos E (2012) Complete mesocolic excision in colon cancer surgery: a comparison between open and laparoscopic approach. Colorectal Dis 14(11):1357–1364. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.03019.x

Hamzaoglu I, Ozben V, Sapci I et al (2018) “Top down no-touch” technique in robotic complete mesocolic excision for extended right hemicolectomy with intracorporeal anastomosis. Tech Coloproctol 22:607–611. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-018-1831-0

Han DP, Lu AG, Feng H, Wang PX, Cao QF, Zong YP, Feng B, Zheng MH (2013) Long-term results of laparoscopy-assisted radical right hemicolectomy with D3 lymphadenectomy: clinical analysis with 177 cases. Int J Colorectal Dis 28(5):623–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-012-1605-5

Han DP, Lu AG, Feng H, Wang PX, Cao QF, Zong YP, Feng B, Zheng MH (2014) Long-term outcome of laparoscopic-assisted right-hemicolectomy with D3 lymphadenectomy versus open surgery for colon carcinoma. Surg Today 44(5):868–874. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-013-0697-z

He Z, Zhang S, Xue P et al (2019) Completely medial access by page-turning approach for laparoscopic right hemi-colectomy: 6-year-experience in single center. Surg Endosc 33:959–965. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6525-1

Ho MLL, Ke TW, Chen WT (2020) Minimally invasive complete mesocolic excision and central vascular ligation (CME/CVL) for right colon cancer. J Gastrointest Oncol 11(3):491–499. https://doi.org/10.21037/jgo.2019.11.08

Huang JL, Wei HB, Fang JF, Zheng ZH, Chen TF, Wei B, Huang Y, Liu JP (2015) Comparison of laparoscopic versus open complete mesocolic excision for right colon cancer. Int J Surg 23(Pt A):12–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.08.037

Kanemitsu Y, Komori K, Kimura K, Kato T (2013) D3 lymph node dissection in right hemicolectomy with a no-touch isolation technique in patients with colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 56(7):815–824. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182919093

Karachun A, Panaiotti L, Chernikovskiy I, Achkasov S, Gevorkyan Y, Savanovich N, Sharygin G, Markushin L, Sushkov O, Aleshin D, Shakhmatov D, Nazarov I, Muratov I, Maynovskaya O, Olkina A, Lankov T, Ovchinnikova T, Kharagezov D, Kaymakchi D, Milakin A, Petrov A (2020) Short-term outcomes of a multicentre randomized clinical trial comparing D2 versus D3 lymph node dissection for colonic cancer (COLD trial). Br J Surg 107(5):499–508. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11387

Kataoka K, Beppu N, Shiozawa M, Ikeda M, Tomita N, Kobayashi H, Sugihara K, Ceelen W (2020) Colorectal cancer treated by resection and extended lymphadenectomy: patterns of spread in left- and right-sided tumours. Br J Surg 107(8):1070–1078. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11517

Killeen S, Mannion M, Devaney A, Winter DC (2014) Complete mesocolic resection and extended lymphadenectomy for colon cancer: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis 16(8):577–594. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.12616

Killeen S, Kessler H (2014) Complete mesocolic excision and central vessel ligation for right colon cancers. Tech Coloproctol 18(11):1129–1131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-014-1214-0

Kim CW, Han YD, Kim HY, Hur H, Min BS, Lee KY, Kim NK (2016) Learning curve for single-incision laparoscopic resection of right-sided colon cancer by complete mesocolic excision. Medicine 95(26):e3982. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000003982

Kim IY, Kim BR, Choi EH, Kim YW (2016) Short-term and oncologic outcomes of laparoscopic and open complete mesocolic excision and central ligation. Int J Surg 27:151–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.02.001

Kim NK, Kim YW, Han YD, Cho MS, Hur H, Min BS, Lee KY (2016) Complete mesocolic excision and central vascular ligation for colon cancer: principle, anatomy, surgical technique, and outcomes. Surg Oncol 25(3):252–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suronc.2016.05.009

Kim JS, Baek SJ, Kwak JM, Kim J, Kim SH, Ji WB, Kim JS, Hong KD, Um JW, Kang SH, Lee SI, Min BW (2021) Impact of D3 lymph node dissection on upstaging and short-term survival in clinical stage I right-sided colon cancer. Asian J Surg S1015–9584(21):00118–00124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asjsur.2021.02.011

Kobayashi H, West NP (2020) CME versus D3 Dissection for Colon Cancer. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 33(6):344–348. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1714237

Koc MA, Celik SU, Guner V, Akyol C (2021) Laparoscopic vs open complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation for right-sided colon cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 100(6):e24613. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000024613

Lan YT, Lin JK, Jiang JK, Chang SC, Liang WY, Yang SH (2011) Significance of lymph node retrieval from the terminal ileum for patients with cecal and ascending colonic cancers. Ann Surg Oncol 18(1):146–152. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-010-1270-2

Larach JT, Rajkomar AKS, Narasimhan V, Kong J, Smart PJ, Heriot AG, Warrier SK (2021) Robotic complete mesocolic excision and central vascular ligation for right-sided colon cancer: short-term outcomes from a case series. ANZ J Surg 91(1–2):117–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.16224

Lee SD, Lim SB (2009) D3 lymphadenectomy using a medial to lateral approach for curable right-sided colon cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis 24(3):295–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-008-0597-7

Lee JM, Chung T, Kim KM, Simon NSM, Han YD, Cho MS, Hur H, Lee KY, Kim NK, Lee SB, Kim GR, Min BS (2020) Significance of radial margin in patients undergoing complete mesocolic excision for colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 63(4):488–496. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000001569

Li J, Zhu S, Juan J, Yi B (2020) Preliminary exploration of robotic complete mesocolic excision for colon cancer with the domestically produced Chinese minimally invasive Micro Hand S surgical robot system. Int J Med Robot 16(6):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/rcs.2148

Liang JT, Lai HS, Huang J, Sun CT (2015) Long-term oncologic results of laparoscopic D3 lymphadenectomy with complete mesocolic excision for right-sided colon cancer with clinically positive lymph nodes. Surg Endosc 29(8):2394–2401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3940-9

Livadaru C, Morarasu S, Frunza TC, Ghitun FA, Paiu-Spiridon EF, Sava F, Terinte C, Ferariu D, Lunca S, Dimofte GM (2019) Post-operative computed tomography scan - reliable tool for quality assessment of complete mesocolic excision. World J Gastrointest Oncol 11(3):208–226. https://doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v11.i3.208

Luglio G, De Palma GD, Tarquini R, Giglio MC, Sollazzo V, Esposito E, Spadarella E, Peltrini R, Liccardo F, Bucci L (2015) Laparoscopic colorectal surgery in learning curve: role of implementation of a standardized technique and recovery protocol. Cohort Study Ann Med Surg (Lond) 4(2):89–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2015.03.003

Melich G, Jeong DH, Hur H, Baik SH, Faria J, Kim NK, Min BS (2014) Laparoscopic right hemicolectomy with complete mesocolic excision provides acceptable perioperative outcomes but is lengthy–analysis of learning curves for a novice minimally invasive surgeon. Can J Surg 57(5):331–336. https://doi.org/10.1503/cjs.002114

Merkel S, Weber K, Matzel KE, Agaimy A, Göhl J, Hohenberger W (2016) Prognosis of patients with colonic carcinoma before, during and after implementation of complete mesocolic excision. Br J Surg 103(9):1220–1229. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10183

Mori S, Baba K, Yanagi M, Kita Y, Yanagita S, Uchikado Y, Arigami T, Uenosono Y, Okumura H, Nakajo A, Maemuras K, Ishigami S, Natsugoe S (2015) Laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision with radical lymph node dissection along the surgical trunk for right colon cancer. Surg Endosc 29(1):34–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3650-3

Mori S, Kita Y, Baba K, Yanagi M, Okumura H, Natsugoe S (2015) Laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision via reduced port surgery for treatment of colon cancer. Dig Surg 32(1):45–51. https://doi.org/10.1159/000373895

Nagasaki T, Akiyoshi T, Fujimoto Y, Konishi T, Nagayama S, Fukunaga Y, Arai M, Ueno M (2015) Prognostic impact of distribution of lymph node metastases in stage III colon cancer. World J Surg 39(12):3008–3015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-015-3190-6

Nakajima K, Inomata M, Akagi T, Etoh T, Sugihara K, Watanabe M, Yamamoto S, Katayama H, Moriya Y, Kitano S (2014) Quality control by photo documentation for evaluation of laparoscopic and open colectomy with D3 resection for stage II/III colorectal cancer: Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study JCOG 0404. Jpn J Clin Oncol 44(9):799–806. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyu083

Olmi S, Oldani A, Cesana G, Ciccarese F, Uccelli M, Giorgi R, Villa R, Maria De Carli S (2020) Surgical outcomes of laparoscopic right colectomy with complete mesocolic excision. JSLS 24(2):00023. https://doi.org/10.4293/JSLS.2020.00023

Olofsson F, Buchwald P, Elmståhl S, Syk I (2016) No benefit of extended mesenteric resection with central vascular ligation in right-sided colon cancer. Colorectal Dis 18(8):773–778. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.13305

Ouyang M, Luo Z, Wu J, Zhang W, Tang S, Lu Y, Hu W, Yao X (2019) Comparison of outcomes of complete mesocolic excision with conventional radical resection performed by laparoscopic approach for right colon cancer. Cancer Manag Res 25(11):8647–8656. https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S203150

Ow ZGW, Sim W, Nistala KRY, Ng CH, Koh FH, Wong NW, Foo FJ, Tan KK, Chong CS (2021) Comparing complete mesocolic excision versus conventional colectomy for colon cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol 47(4):732–737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2020.09.007

Ozben V, Aytac E, Atasoy D et al (2019) Totally robotic complete mesocolic excision for right-sided colon cancer. J Robotic Surg 13:107–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11701-018-0817-2

Pedrazzani C, Lazzarini E, Turri G, Fernandes E, Conti C, Tombolan V, Nifosì F, Guglielmi A (2019) Laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision for right-sided colon cancer: analysis of feasibility and safety from a single western center. J Gastrointest Surg 23(2):402–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-018-4040-2

Perrakis A, Vassos N, Weber K, Matzel KE, Papadopoulos K, Koukis G, Perrakis E, Croner RS, Hohenberger W (2019) Introduction of complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation as standardized surgical treatment for colon cancer in Greece. results of a pilot study and bi-institutional cooperation. Arch Med Sci 5:1269–1277. https://doi.org/10.5114/aoms.2018.80040

Petz W, Ribero D, Bertani E, Borin S, Formisano G, Esposito S, Spinoglio G, Bianchi PP (2017) Suprapubic approach for robotic complete mesocolic excision in right colectomy: oncologic safety and short-term outcomes of an original technique. Eur J Surg Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2017.07.020

Pramateftakis MG (2010) Optimizing colonic cancer surgery: high ligation and complete mesocolic excision during right hemicolectomy. Tech Coloproctol 14(Suppl 1):S49-51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-010-0609-9

Prevost GA, Odermatt M, Furrer M, Villiger P (2018) Postoperative morbidity of complete mesocolic excision and central vascular ligation in right colectomy: a retrospective comparative cohort study. World J Surg Oncol 16(1):214. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-018-1514-3

Ramachandra C, Sugoor P, Karjol U, Arjunan R, Altaf S, Patil V, Kumar H, Beesanna G, Abhishek M (2020) Robotic complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation for right colon cancer: surgical technique and short-term outcomes. Indian J Surg Oncol 11(4):674–683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13193-020-01181-9

Rinne JK, Ehrlich A, Ward J, Väyrynen V, Laine M, Kellokumpu IH, Kairaluoma M, Hyöty MK, Kössi JA (2021) Laparoscopic colectomy vs laparoscopic CME: a retrospective study of two hospitals with comparable laparoscopic experience. J Gastrointest Surg 25(2):475–483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-019-04502-8

Sahara K, Watanabe J, Ishibe A, Goto K, Takei S, Suwa Y, Suwa H, Ota M, Kunisaki C, Endo I (2021) Optimal extent of central lymphadenectomy for right-sided colon cancers: is lymphadenectomy beyond the superior mesenteric vein meaningful? Surg Today 51(2):268–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-020-02084-6

Sammour T, Malakorn S, Thampy R, Kaur H, Bednarski BK, Messick CA, Taggart M, Chang GJ, You YN (2020) Selective central vascular ligation (D3 lymphadenectomy) in patients undergoing minimally invasive complete mesocolic excision for colon cancer: optimizing the risk-benefit equation. Colorectal Dis 22(1):53–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.14794

Sheng QS, Pan Z, Chai J, Cheng XB, Liu FL, Wang JH, Chen WB, Lin JJ (2017) Complete mesocolic excision in right hemicolectomy: comparison between hand-assisted laparoscopic and open approaches. Ann Surg Treat Res 92(2):90–96. https://doi.org/10.4174/astr.2017.92.2.90

Shin JW, Amar AH, Kim SH, Kwak JM, Baek SJ, Cho JS, Kim J (2014) Complete mesocolic excision with D3 lymph node dissection in laparoscopic colectomy for stages II and III colon cancer: long-term oncologic outcomes in 168 patients. Tech Coloproctol 18(9):795–803. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-014-1134-z

Shin JK, Kim HC, Lee WY, Yun SH, Cho YB, Huh JW, Park YA, Chun HK (2018) Laparoscopic modified mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation in right-sided colon cancer shows better short- and long-term outcomes compared with the open approach in propensity score analysis. Surg Endosc 32(6):2721–2731. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-017-5970-6

Siani LM, Pulica C (2015) Laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation in right colon cancer: long-term oncologic outcome between mesocolic and non-mesocolic planes of surgery. Scand J Surg 104(4):219–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1457496914557017

Siddiqi N, Stefan S, Jootun R et al (2021) Robotic complete mesocolic excision (CME) is a safe and feasible option for right colonic cancers: short and midterm results from a single-centre experience. Surg Endosc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-08194-z

Spinoglio G, Marano A, Bianchi PP, Priora F, Lenti LM, Ravazzoni F, Formisano G (2016) Robotic right colectomy with modified complete mesocolic excision: long-term oncologic outcomes. Ann Surg Oncol 23(Suppl 5):684–691. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-016-5580-x

Spinoglio G, BianchiPP MA, Priora F, Lenti LM, Ravazzoni F, Petz W, Borin S, Ribero D, Formisano G, Bertani E (2018) Robotic versus laparoscopic right colectomy with complete mesocolic excision for the treatment of colon cancer: perioperative outcomes and 5-year survival in a consecutive series of 202 patients. Ann Surg Oncol 25(12):3580–3586. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-018-6752-7

Storli KE, Søndenaa K, Furnes B, Nesvik I, Gudlaugsson E, Bukholm I, Eide GE (2014) Short term results of complete (D3) vs. standard (D2) mesenteric excision in colon cancer shows improved outcome of complete mesenteric excision in patients with TNM stages I-II. Tech Coloproctol 18(6):557–564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-013-1100-1

Storli KE, Søndenaa K, Furnes B, Eide GE (2013) Outcome after introduction of complete mesocolic excision for colon cancer is similar for open and laparoscopic surgical treatments. Dig Surg 30(4–6):317–327. https://doi.org/10.1159/000354580

Subbiah R, Bansal S, Jain M, Ramakrishnan P, Palanisamy S, Palanivelu PR, Chinusamy P (2016) Initial retrocolic endoscopic tunnel approach (IRETA) for complete mesocolic excision (CME) with central vascular ligation (CVL) for right colonic cancers: technique and pathological radicality. Int J Colorectal Dis 31(2):227–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-015-2415-3

Takahashi H, Takemasa I, Haraguchi N, Nishimura J, Hata T, Yamamoto H, Matsuda C, Mizushima T, Doki Y, Mori M (2017) The single-center experience with the standardization of single-site laparoscopic colectomy for right-sided colon cancer. Surg Today 47(8):966–972. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-016-1457-7

Thorsen Y, Stimec B, Andersen SN, Lindstrom JC, Pfeffer F, Oresland T, Ignjatovic D (2016) RCC study group. Bowel function and quality of life after superior mesenteric nerve plexus transection in right colectomy with D3 extended mesenterectomy. Tech Coloproctol 20(7):445–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-016-1466-y

Thorsen Y, Stimec BV, Lindstrom JC, Nesgaard JM, Oresland T, Ignjatovic D (2019) Bowel motility after injury to the superior mesenteric plexus during D3 extended mesenterectomy. J Surg Res 239:115–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2019.02.004

Takemasa I, Uemura M, Nishimura J, Mizushima T, Yamamoto H, Ikeda M, Sekimoto M, Doki Y, Mori M (2014) Feasibility of single-site laparoscopic colectomy with complete mesocolic excision for colon cancer: a prospective case-control comparison. Surg Endosc 28(4):1110–1118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-013-3284-x

Tominaga T, Yamaguchi T, Nagasaki T et al (2021) Improved oncologic outcomes with increase of laparoscopic surgery in modified complete mesocolic excision with D3 lymph node dissection for T3/4a colon cancer: results of 1191 consecutive patients during a 10-year period: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Clin Oncol 26:893–902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-021-01870-7

Wang Y, Zhang C, Zhang D, Fu Z, Sun Y (2017) Clinical outcome of laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision in the treatment of right colon cancer. World J Surg Oncol 15(1):174. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-017-1236-y

Wei M, Zhang X, Ma P, He W, Bi L, Wang Z (2018) Outcomes of open, laparoscopic, and hand-assisted laparoscopic surgeries in elderly patients with right colon cancers: a case-control study. Medicine 97(35):e11907. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000011907

West NP, Morris EJA, Rotimi O et al (2008) Pathol- ogy grading of colonic cancer surgical resection and its relationship to survival: a retrospective observa- tional study. Lancet Oncol 9:857–865

Willard CD, Kjaestad E, Stimec BV et al (2019) Preoperative anatomical road mapping reduces variability of operating time, estimated blood loss, and lymph node yield in right colectomy with extended D3 mesenterectomy for cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis 34:151–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-018-3177-5

Wu QB, Deng XB, Yang XY, Chen BC, He WB, Hu T, Wei MT, Wang ZQ (2017) Hand-assisted laparoscopic right hemicolectomy with complete mesocolic excision and central vascular ligation: a novel technique for right colon cancer. Surg Endosc 31(8):3383–3390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-016-5354-3

Wu H, Chen G, Li W, Xu L, Jin P, Zheng Z (2020) Short- and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision for colon cancer in the elderly: a retrospective cohort study. J BUON 25(4):1832–1839

Xie D, Yu C, Gao C, Osaiweran H, Hu J, Gong J (2017) An optimal approach for laparoscopic D3 lymphadenectomy plus complete mesocolic excision (D3+CME) for right-sided colon cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 24(5):1312–1313. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-016-5722-1

Yamamoto M, Asakuma M, Tanaka K, Masubuchi S, Ishii M, Osumi W, Hamamoto H, Okuda J, Uchiyama K (2019) Clinical impact of single-incision laparoscopic right hemicolectomy with intracorporeal resection for advanced colon cancer: propensity score matching analysis. Surg Endosc 33(11):3616–3622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-06647-0

Yan D, Yang X, Duan Y, Zhang W, Feng L, Wang T, Du B (2020) Comparison of laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision and traditional radical operation for colon cancer in the treatment of stage III colon cancer. J BUON 25(1):220–226

Yang Y, Malakorn S, Zafar SN, Nickerson TP, Sandhu L, Chang GJ (2019) Superior mesenteric vein-first approach to robotic complete mesocolic excision for right colectomy: technique and preliminary outcomes. Dis Colon Rectum 62(7):894–897. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000001412

Yi X, Li H, Lu X, Wan J, Diao D (2020) “Caudal-to-cranial” plus “artery first” technique with beyond D3 lymph node dissection on the right midline of the superior mesenteric artery for the treatment of right colon cancer: is it more in line with the principle of oncology? Surg Endosc 34(9):4089–4100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-019-07171-5

Yozgatli TK, Aytac E, Ozben V, Bayram O, Gurbuz B, Baca B, Balik E, Hamzaoglu I, Karahasanoglu T, Bugra D (2019) Robotic complete mesocolic excision versus conventional laparoscopic hemicolectomy for right-sided colon cancer. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 29(5):671–676. https://doi.org/10.1089/lap.2018.0348

Zedan A, Elshiekh E, Omar MI, Raafat M, Khallaf SM, Atta H, Hussien MT (2021) Laparoscopic versus open complete mesocolic excision for right colon cancer. Int J Surg Oncol 2(2021):8859879. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8859879

Zhao LY, Liu H, Wang YN, Deng HJ, Xue Q, Li GX (2014) Techniques and feasibility of laparoscopic extended right hemicolectomy with D3 lymphadenectomy. World J Gastroenterol 20(30):10531–10536. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10531

Zhao LY, Chi P, Ding WX, Huang SR, Zhang SF, Pan K, Hu YF, Liu H, Li GX (2014) Laparoscopic vs open extended right hemicolectomy for colon cancer. World J Gastroenterol 20(24):7926–7932. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i24.7926

Zurleni T, Cassiano A, Gjoni E et al (2018) Surgical and oncological outcomes after complete mesocolic excision in right-sided colon cancer compared with conventional surgery: a retrospective, single-institution study. Int J Colorectal Dis 33:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-017-2917-2

Watanabe T, Itabashi M, Shimada Y et al (2012) Japanese society for cancer of the colon and rectum. japanese society for cancer of the colon and rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2010 for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol 17:1–29

Bertelsen CA, Neuenschwander AU, Jansen JE et al (2015) Danish colorectal cancer group. Disease-free survival after complete mesocolic excision compared with conventional colon cancer surgery: a retrospective, population-based study. Lancet Oncol 16:161–168

Emmanuel A, Haji A (2016) Complete mesocolic excision and extended (D3) lymphadenectomy for colonic cancer: is it worth that extra effort? A review of the literature. Int J Colorectal Dis 31:797–804

Sjo OH, Merok MA, Svindland A et al (2010) Prognostic impact of lymph node harvest and lymph node ratio in patients with colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 55:307–315

Garcia-Granero A, Pellino G, Frasson M, Fletcher-Sanfeliu D, Bonilla F, Sánchez-Guillén L et al (2019) The fusion fascia of Fredet: an important embryological landmark for complete mesocolic excision and D3-lymphadenectomy in right colon cancer. Surg Endosc 33(11):3842–3850

Bellomaria A, Barbato G, Melino G, Paci M, Melino S (2010) Recognition of p63 by the E3 ligase ITCH: Effect of an ectodermal dysplasia mutant. Cell Cycle 9(18):3730–3739

Bucciarelli T, Sacchetta P, Pennelli A, Cornelio L, Romagnoli R, Melino S, Petruzzelli R, Di Ilio C (1999) Characterization of toad liver glutathione transferase. Biochim Biophys Acta 1431(1):189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00036-9

Nepravishta R, Sabelli R, Iorio E, Micheli L, Paci M, Melino S (2012) Oxidative species and S-glutathionyl conjugates in the apoptosis induction by allyl thiosulfate. FEBS J 279(1):154–167. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08407.x

Lamastra FR, De Angelis R, Antonucci A, Salvatori D, Prosposito P, Casalboni M, Congestri R, Melino S, Nanni F (2014) Polymer composite random lasers based on diatom frustules as scatterers. RSC Adv 4(106):61809–61816

Gillot C, Hureau J, Aaron C, Martini R, Thaler G, Michels NA (1964) The superior mesenteric vein, an anatomic and surgical study of eighty-one subjects. J Int Coll Surg 41:339–369

Toyota S, Ohta H, Anazawa S (1995) Rationale for extent of lymph node dissection for right colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 38(705–711):30

Hashiguchi Y, Hase K, Ueno H, Mochizuki H, Shinto E, Yamamoto J (2011) Optimal margins and lymphadenectomy in colonic cancer surgery. Br J Surg 98(1171–1178):31

Kotake K, Honjo S, Sugihara K, Hashiguchi Y, Kato T, Kodaira S, Muto T, Koyama Y (2012) Number of lymph nodes retrieved is an important determinant of survival of patients with stage II and stage III colorectal cancer. Jap J Clin Oncol 42(1):29–35

Kobayashi H, Ueno H, Hashiguchi Y, Mochizuki H (2006) Distribution of lymph node metastasis is a prognostic index in patients with stage III colon cancer. Surgery 139:516–522

Merrie AEH, Phillips LV, Yun K, McCall JL (2001) Skip metastases in colon cancer: assessment by lymph node mapping using molecular detection. Surgery 129(684–691):36

Tan KY, Kawamura YJ, Mizokami K, Sasaki J, Tsujinaka S, Maeda T, Nobuki M, Konishi F (2010) Distribution of the first metastatic lymph node in colon cancer and its clinical significance. Color Dis 12:44–47

EuroSurg Collaborative (2018) Body mass index and complications following major gastrointestinal surgery: a prospective, international cohort study and meta-analysis. Colorectal Disease 20(8):0215–0225. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.14292

Rossi P, Sileri P, Gentileschi P et al (2001) Percutaneous liver biopsy using an ultrasound-guided subcostal route. Dig Dis Sci 46(1):128–132. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1005571904713

Freund MR, Edden Y, Reissman P, Dagan A (2016) Iatrogenic superior mesenteric vein injury: the perils of high ligation. Int J Colorectal Dis 31:1649–1651

Cancer predictive studies (2020) Amelio I, Bertolo R, Bove P, Candi E, Chiocchi M, Cipriani C, Di Daniele N, Ganini C, Juhl H, Mauriello A, Marani C, Marshall J, Montanaro M, Palmieri G, Piacentini M, Sica G, Tesauro M, Rovella V, Tisone G, Shi Y, Wang Y, Melino G. Biol Direct 15(1):18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13062-020-00274-3

Sileri P, Sica G, Gentileschi P, Venza M, Manzelli A, Palmieri G, Spagnoli LG, Testa G, Benedetti E, Gaspari AL (2004) Ischemic preconditioning protects intestine from prolonged ischemia. Transplantation Proceedings 36(2):283–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.01.078

Bertelsen CA, Bols B, Ingeholm P, Jansen JE, Jepsen LV, Kristensen B, Neuenschwander AU, Gögenur I (2014) Lymph node metastases in the gastrocolic ligament in patients with colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 57(7):839–845. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000000144

Benz S, Tannapfel A, Tam Y, Grünenwald A, Vollmer S, Stricker I (2019) Proposal of a new classification system for complete mesocolic excision in right-sided colon cancer. Tech Coloproctol 23:251–257

Garcia-Granero A, Pellino G, Giner F et al (2020) A proposal for novel standards of histopathology reporting for D3 lymphadenectomy in right colon cancer: the mesocolic sail and superior right colic vein landmarks. Dis Colon Rectum 63:450–460

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Roma Tor Vergata within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This research did not receive any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: GSS. Design: GSS, DV, GP. Data extraction and synthesis: DV, LS, BS, AMG. Writing: DV, LS, BS, VB, GSS. Review for major intellectual concepts: GSS, VB, GP, AGG. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure

Giuseppe S. Sica, Danilo Vinci, Leandro Siragusa, Bruno Sensi, Andrea Guida, Vittoria Bellato, Alvaro Garcia-Granero and Gianluca Pellino have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Ethical approval

According to local IRB, ethical approval for systematic review is not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article was updated to correct the CME+D3 data in the text and Table 2.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sica, G.S., Vinci, D., Siragusa, L. et al. Definition and reporting of lymphadenectomy and complete mesocolic excision for radical right colectomy: a systematic review. Surg Endosc 37, 846–861 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-022-09548-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-022-09548-5