Abstract

Introduction

Guided by enhanced recovery after surgery protocols and coerced by constraints of the Coronavirus Disease 2019, the concept of same day discharge (SDD) after colon surgery is becoming a topic of great interest. Although only a few literature sources are published on the topic and protocols, the number of centers interested in SDD is increasing. With the small number of sources on protocol, safety, implementation, and criteria, there has yet to be a review of the patient experience and satisfaction.

Methods

Our institution has one of the largest American databases of SDD colon surgery. We performed a retrospective patient survey assessing perception of their surgical experience and satisfaction, which analyzed patients from February 2019 to January 2022. Fifty SDD patients were selected for participation, as well as fifty patients who were discharged on postoperative day 1 (POD1). An eleven-question survey was offered to patients and responses recorded.

Results

One hundred patients were contacted, 50 SDD and 50 POD1. Of the SDD patients, 41/50 (82%) patients participated in the survey, while 23/50 (46%) of POD1 patients participated. The highest average response in both populations was an understanding of patient postoperative mobility instructions (9.27/10, 9.68/10). The lowest average response in the SDD population was family comfort with discharge (8.17/10), while patient comfort with discharge was lowest in the POD1 group, (8.56/10). Importantly, we observed that 85.37% of patients who underwent SDD would do so again if given the opportunity. The only statistically significant variable was a difference in comfort with postoperative pain control, favoring the POD1 group, p = 0.02.

Conclusions

SDD colon surgery is a feasible and reproducible option. Only comfort with postoperative pain control found a statistical difference, which we intend to improve upon with postanesthesia care unit education. Of patients reviewed who underwent SDD, most patients enjoyed their experience and would undergo SDD again.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Same day discharge (SDD) after colon surgery is an emerging topic for which significant resources are being applied. The recent surge in interest stems from a combination of aspects, primarily the success of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols and demands made by the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID 19). With the COVID 19 virus we have witnessed considerable strain on healthcare systems [1]. Notably, this has resulted in shortages of staff, products, and equipment [1]. Additionally, surgeons have had to alter their practice by entertaining nonsurgical options, minimally invasive approaches, triaging procedures based on urgency, and minimizing length of stay (LOS) [1]. Fortunately, many institutions have colorectal ERAS protocols in place, for which the main tenets rest upon appropriate patient selection, patient preoperative optimization, and minimally invasive approaches to surgery [2]. As a result of both ERAS protocols and minimally invasive surgical techniques, research has found that overall length of stay has decreased [3]. With ERAS protocols there has been a decrease in LOS by 1–2 days, and minimally invasive procedures by 2–3 days when compared to open surgery [3,4,5]. Guided by the established success of ERAS protocols and coerced by the burden of COVID 19 constraints, SDD protocols were produced.

Our institution saw initial success with ERAS protocols, and now for the past 2 years has routinely been practicing SDD colon surgery in the appropriate patient population. The ability to perform SDD in the current global pandemic has allowed for better utilization of hospital resources, decreased inpatient patient risk, and reduced burden on limited hospital staff. Although, hospital systems view these aspects of SDD as successful and due to the pandemic now essential, the question of patient perception is now being asked. Patients undergoing these procedures were formally staying in the hospital for several days, but now they’re being discharged in just mere hours [3,4,5]. Prior data on ERAS protocols showed that patients were appreciative of the increased understanding of perioperative expectations, improved communication with medical teams, and decreased LOS [6]. Although this response has been witnessed with established ERAS protocols, SDD platforms are much younger, and this information is lacking. As such, after extensive literature review, we are unable to locate any reports focusing on the patient perception of SDD after colon surgery. Clinicians may find the ability to safely discharge a patient after major surgery in just mere hours a great success, however physicians are not the only party involved in that decision.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to perform a survey to analyze patient experience and satisfaction with same day discharge after colon surgery. Additionally, these results were compared to the experience of patients who were discharged on postoperative day 1.

Materials and methods

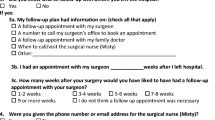

A retrospective review of patients who underwent colon surgery between February 2019 and January 2022 was performed. The patients were separated into two distinct categories, those who were discharged on the same day and those who were not. For all non-SDD patients, the group was further defined by postoperative day (POD) 1 discharge or discharge on later days. All patients who were discharged later than POD1 were removed from this study. Our two patient populations consisted of those who underwent SDD (n = 69), and our control group of those who underwent discharge on POD1 (n = 154). Procedures performed in either group included: cecectomy, right colectomy, transverse colectomy, left colectomy, low anterior resection, proctectomy, ostomy reversal with resection, or rectopexy. Of the two groups, fifty patients were randomly selected from each group and were contacted to request participation in the study. These patients were selected randomly based on the order they were populated into our electronic medical record databank. The survey consisted of eleven questions that assessed patient experience, preference, satisfaction, and any comments (Figs. 1 and 2). The questions were posed in different formats including multiple choice, yes/no, and ranking scale from one to ten. Additionally, at the end of the survey there was a comment section where patient feedback could be recorded. The patients were contacted via phone to complete the survey, or the study was completed in person at the time of postoperative assessment. All the patient surveys were conducted by two of the authors (KRC, CLK). Once the patients completed the survey, no further contact was made regarding the survey or their responses. They were not required to provide any explanation of their responses, however if patients elaborated on their response, this was recorded in the comments section. A total of three attempts were made to contact the patient by phone and if the patient did not answer on the third attempt, no additional attempts were made. No voicemail messages were left. Once answers were obtained, they were numerically recorded into a new blinded dataset for assessment and analyzation by the other authors.

Results

A total of one hundred patients were contacted during the production of this study and divided into two groups, SDD (n = 50) and POD1 (n = 50). Of the patients who underwent SDD, 41/50 (82%) patients participated in the survey, while nine patients did not answer after the third attempt. From the POD1 patient population, 23/50 (46%) patients completed the survey, while 27 patients did not answer after three attempts. There were no patients who refused participation in this study.

The average response to each question was collected and recorded in Table 1. In SDD, the lowest average score was assessment of family/support system comfort with discharge (8.17/10), in which POD 1 reported a score of (8.96/10), p = 0.15. The highest score for both groups was understanding postoperative mobility instructions, SDD (9.27/10) and POD 1 (9.68/10), p = 0.20. The lowest POD1 score was for patient comfort with discharge (8.56/10), while SDD in this category reported (8.22/10), p = 0.32. Comfort with postoperative diet was the only value higher in SDD (9.17/10), compared to POD1 (8.96), though again not statistically significant, p = 0.52. The only statistically significant difference was identified in patient comfort with postoperative pain control, SDD (8.34/10) and POD 1 (9.48/10), p = 0.02.

Additionally, 38/41 (92.68%) SDD responders found that they could easily contact our office with questions of concerns, while all 23 (100%) POD1 reported these findings. Furthermore, in SDD 39/41 (95.12%) patients felt they received enough preoperative education on expectations, in POD1 22/23 (95.65%) reported enough preoperative education. Next, 36/41 (87.80%) SDD patients felt that they played an active role in the decision making for discharge, 87.80%, while all 23/23 (100%) POD1 patients reported feeling an active role. Lastly, 35/41 (85.37%) of SDD patients stated that if they needed another similar procedure, they would want to undergo SDD again. In POD1, 22/23 (95.65%), would desire a POD1 discharge if offered.

Finally, the patients were asked about in which format they would prefer to receive instructions regarding their medical care. Both groups favored receiving instructions in a written format (SDD 32/39 [82.1%], POD1 18/23 [78.26%]). While some patients preferred video format (SDD 4/39 [10.26%], POD1 2/23 [8.7%]), either format (SDD 2/39 [5.13%], POD1 2/23 [8.7%]) or both formats (SDD 1/39 [2.56%], POD1 1/23 [4.35%]).

Discussion

When reviewing the patient responses, we received enlightening comments that must be entertained for improving our protocol employed. In the SDD population, there were two patients who reported that they did not receive enough education regarding their care. Although patients were not required to elaborate on their responses, both patients further commented that they felt rushed to leave the post anesthesia care unit (PACU), and under the influence of anesthesia medications when receiving postoperative instructions. Additionally, five patients responded that they did not feel they had an active role in their discharge decision making. Of those five, three patients cited that they did not yet feel ready to leave PACU; one of these also stated they did not have adequate home pain control. The other two patients who reported that they did not feel they had a role in their discharge stated that they were unable to stay due to bed shortages from the COVID 19 pandemic. Lastly, 35/41 (85.37%) SDD patients stated that they would undergo SDD again if they needed a similar procedure. While reviewing the patient responses of those who would not repeat SDD, four of the five patients who reported a decreased role in decision making stated they would not want to undergo SDD again (3 not feeling ready for PACU discharge, 1 COVID 19 limiting bed). The cause for the remaining two patients who would not undergo repeat SDD included emergency room assessment for urinary retention and again feeling PACU discharge was premature. In the comment section, 33 patients responded. Most patients (25/33, 75.6%) reported a favorable experience. These comments included compliments to the surgeon, office staff, anesthesia team, and nursing staff. Furthermore, patients elaborated and reported they were pleased with the amount of time taken for explanation, the personal bedside manner, and ensured understanding by the patient and family. Many patients reported feeling safe throughout the entire experience, and several reported wanting future surgeries performed in the same manner. The only negative comments received were previously discussed and were regarding early PACU discharge, postoperative urinary retention, pain control management, or decreased ability to contact the office.

Briefly contrasting these responses to those of the POD 1 population, similar responses were given. It was identified that the same POD1 patient who reported not receiving enough preoperative education also reported not wanting to be discharged on POD 1 again if another similar procedure was needed. Unfortunately, the patient did not leave other comments in the survey. The other reported POD1 comments again mentioned compliments to multiple different teams involved in care, the extensive time provided for understanding, good bedside manner, and increased level of comfort and safety throughout the perioperative process. The negative comments received in the POD 1 population again reported feeling a rush for discharge, decreased preoperative education, and concerns over postoperative pain control. When comparing the SDD and POD 1 populations, many compliments and complaints were similar between the two groups. Additionally, statistically the only significant difference identified was concerning comfort with postoperative pain control.

From our experience and previously published data, we know that SDD after colectomy is a safe and feasible option in the proper patient population [7,8,9,10,11]. As clinicians pressured by constraints of the current COVID 19 pandemic, we have viewed upgrading our ERAS protocols into SDD regimens as a success. However, we must remember that we are not the only parties involved when SDD is being performed. As was previously done with ERAS protocols, the patient perspective must also be analyzed and considered [12]. ERAS protocols found clinical measures of improvement when compared to non-ERAS surgery, such as decreased hospital LOS and cost [12]. Importantly however, there has also been ERAS literature published that reviewed patient satisfaction and assessed of quality of life [12, 13]. ERAS protocols were found to have a sooner return to work, sensation of feeling well informed, higher comfort level at home, less patient fatigue, and no detriment to patient satisfaction or quality of life [12, 13]. Additionally, ERAS reports have also found that patients appreciated: experiencing less gastrointestinal symptoms, lack of urinary catheters, reduced preoperative fasting, early return of postoperative diet, and decrease in unnecessarily prolonged hospital stay [6].

With SDD being in its infancy, the robust review of both clinical data and the patient perspective has been limited. We have found few studies reporting clinical SDD outcomes and no studies focusing on the patient perception of SDD [7,8,9,10,11]. Through our survey, we identified many factors that patients found beneficial in their experience. Most patients felt that they were active decision makers in their care and discharge plan, as well as reported a heightened level of both patient and family comfort with discharge. Furthermore, a staggering number of patients reported that they felt comfortable with the preoperative education they received and with the instructions they were provided on discharge. Additionally based on interpretation of patient comments, we found that patients felt they had an increased understanding of their care and a sense of empowerment and involvement. Finally, we saw that a large population of patients who underwent SDD (85.37%) would undergo SDD colectomy again. The only identified statistically significant variable was patient comfort with postoperative pain control, which favored the POD1 population. The main complaint received related to feeling rushed for PACU discharge. Through increased PACU staff education and adherence to protocol, we hope to minimize that sensation while improving comfort with postoperative pain control. Aside from that single factor, there were no other statistically significant variables from the patient perspective. Given these results, we feel that after improving PACU education on patient understanding and pain control, SDD is viewed as a viable option by colectomy patients.

Limitations

While performing a retrospective survey on patient experience, we must acknowledge that limitations are encountered. First, this is a retrospective study on patient experience spanning a 2-year period. Patients, especially those who underwent surgery at the beginning of the period, may be influenced by recall bias and base their responses on currently feeling well. Additionally, we must acknowledge the gross difference in response rates between the two populations. Where 82% of SDD responded to the survey, only 46% of the POD 1 population responded. It is one of the main criteria for SDD eligibility that adequate means of communication are available so that any concerns can be relayed, and patients be contacted for status assessments. As such, this factor appears to be clearly reflected again in our response rates to this survey.

Conclusion

After analysis of patient perspectives on SDD colon surgery, the vast majority (85.37%) prefer this method to any length of stay. The combination of an at home support system, ability for office contact, proper education, and ensured patient understanding allowed for increased patient satisfaction with SDD protocols. Only one of the several factors analyzed, comfort with postoperative pain control, was found to be statistically significant favoring POD1. By improving PACU education and postoperative pain control, combined with the evidence that no other responses were statistically significant, we feel that SDD is perceived as a noninferior, patient appreciated alternative to POD 1 discharge.

References

Al-Jabir A, Kerwan A, Nicola M et al (2020) Impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on surgical practice—part 2 (surgical prioritisation). Int J Surg 79:233–248

Carmichael JC, Keller DS, Baldini G et al (2017) Clinical practice guidelines for enhanced recovery after colon and rectal surgery from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons and Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. Dis Colon Rectum 60:761–784

Miller TE, Thacker JK, White WD et al (2014) Reduced length of hospital stay in colorectal surgery after implementation of an enhanced recovery protocol. Anesth Analg 118(5):1052–1061

Sheetz KH, Norton EC, Dimick JB et al (2020) Perioperative outcomes and trends in the use of robotic colectomy for medicare beneficiaries from 2010 through 2016. JAMA Surg 155(1):41–49

Papageorge CM, Zhao Q, Foley EF et al (2016) Short-term outcomes of minimally invasive versus open colectomy for colon cancer. J Surg Res 204(1):83–93

Zychowicz A, Pisarska M, Laskawska A et al (2019) Patients’ opinions on enhanced recovery after surgery perioperative care principles: a questionnaire study. Wideochir Inne Tech 14(1):27–37

McKenna NP, Bews KA, Shariq OA et al (2020) Is same-day and next-day discharge after laparoscopic colectomy reasonable in select patients? Dis Colon Rectum 63(10):1427–1435

Campbell S, Fichera A, Thomas S et al (2021) Outpatient colectomy—a dream or reality. In: Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings

Gignoux B, Gosgnach M, Lanz T et al (2019) Short-term outcomes of ambulatory colectomy for 157 consecutive patients. Ann Surg 270(2):317–321

Bourgouin S, Monchal T, Schlinenger G et al (2020) Eligibility criteria for ambulatory colectomy. J Visc Surg. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2020.11.012

Chasserant P, Gosgnach M (2016) Improvement of peri-operative patient management to enable outpatient colectomy. J Visc Surg. 153(5):333–337

Li D, Jensen CC (2019) Patient satisfaction and quality of life with enhanced recovery protocols. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 32(2):138–144

Wennstrom B, Johansson A, Kalabic S et al (2020) Patient experience of health and care when undergoing colorectal surgery within the ERAS program. Perioper Med. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13741-020-00144-6

Acknowledgements

The authors received no funding or specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors in the production of this study or the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

This study did not receive any funding support from any organization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Contributors to conception, design, acquisition of data, and interpretation of data: KRC, GEB, SAP, CLK and LR. Manuscript writing and drafting: KRC, GEB and LR. Revising it critically for important intellectual content: KRC, GEB, SAP, CLK and LR. Final approval of the version to be published: KRC, GEB, SAP, CLK and LR.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Dr. Laila Rashidi has an honorarium teaching relationship with CSATS and Intuitive Surgical, however this did not have any impact on the study presented within. Dr. Karleigh Curfman, MD, Gabrielle Blair, Sunshine Pille PA-C, Callan Kosnik PA-C, have no conflicts of interest or financial relationships to disclose. We would like to report that this study has only been submitted for review for publication in Surgical Endoscopy. An abstract of this paper has been accepted for presentation at the American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress in October 2022.

Ethical approval

Given the nature of the retrospective patient survey, this study was found to be exempt from approval by our Institutional Review Board.

Informed consent

Due to the retrospective nature of the survey after surgery was completed and no new patient medical information recorded, the consent process for participation was waived by our Institutional Review Board. No patient specific information is included in the study. Only authors involved in the study were able to access patient data to produce information pertinent to this study and then patient specific information was immediately deleted and none was saved.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Curfman, K.R., Blair, G.E., Pille, S.A. et al. The patient perspective of same day discharge colectomy: one hundred patients surveyed on their experience following colon surgery. Surg Endosc 37, 134–139 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-022-09446-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-022-09446-w